Abstract

Introduction

The acute surgical model has been trialled in several institutions with mixed results. The aim of this study was to determine whether the acute surgical model provides better outcomes for patients with acute biliary presentation, compared with the traditional emergency surgery model of care.

Methods

A retrospective review was carried out of patients who were admitted for management of acute biliary presentation, before and after the establishment of an acute surgical unit (ASU). Outcomes measured were time to operation, operating time, after-hours operation (6pm – 8am), length of stay and surgical complications.

Results

A total of 342 patients presented with acute biliary symptoms and were managed operatively. The median time to operation was significantly reduced in the ASU group (32.4 vs 25.4 hours, p=0.047), as were the proportion of operations performed after hours (19.5% vs 2.5%, p<0.001) and the median length of stay (4 vs 3 days, p<0.001). The median operating time, rate of conversion to open cholecystectomy and wound infection rates remained similar.

Conclusions

Implementation of an ASU can lead to objective differences in outcomes for patients who present with acute cholecystitis. In our study, the ASU significantly reduced time to operation, the number of operations performed after hours and length of stay.

Keywords: General surgery, Cholecystectomy, Gallbladder diseases, Cholecystitis

The acute surgical model (ASM) is a new fundamental shift in the restructuring of the management of acute general surgical presentation in Australia. In light of the preliminary results, trials of ASM implementation have been carried out in several institutions with mixed results.1–9 The ASM was envisioned to allow a dedicated consultant-led team to manage acute surgical presentations efficiently and effectively. This coincides partly with the Australian healthcare service model that encourages greater patient flow in the emergency department.10

In the traditional emergency surgery model, patients were managed by an on-call consultant surgeon after being assessed by the acute surgical registrar. Ongoing care at the registrar level would then be handed over to the registrar of the unit to which the on-call consultant belonged. Patients were booked into a common emergency surgery list shared by other surgical specialties and obstetrics. Theatre allocation uncertainty coupled with the fact that most on-call consultants were visiting medical officers with external commitments at other centres had often led to prolonged time to surgery.

Monash Medical Centre (MMC) is a tertiary metropolitan referral hospital in Victoria, Australia. MMC established the acute surgical unit (ASU), which was based on the ASM, on 18 July 2011. The MMC ASU comprises ten upper gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary specialist surgeons as well as two general surgeons, who are all trained to manage the various complexities of acute gallbladder presentation and its complications. The ASU surgeons are also visiting medical officers of the upper gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary unit in the hospital.

The introduction of the ASU at our site allowed for a consultant surgeon to be rostered during daylight hours and on call exclusively after hours. Consultants rotate every 24 hours, beginning at 7pm every day. They are freed from elective surgical commitments and guide the management of patients in the unit for the 24-hour period. The dedicated ASU team is completed by three rotating surgical registrars, one surgical resident and two surgical interns, with continuity of care ensured at the registrar level. Postoperative patients needing a stay of more than 48 hours are transferred to the respective specialist surgeon’s unit. A consultant-led ward round is conducted every morning. This is followed by an exclusive ASU theatre made available every afternoon (1–5pm), except Sundays, to ensure there is no conflict for theatre availability with elective procedures.

The impact of the ASU on appendicectomy outcomes was reviewed at MMC in 2013.11 A significant decrease in the number of operations performed after hours was shown, without any significant decrease in objective outcomes. In light of this previous study, we chose to review the impact of the ASU on the surgical management of acute gallbladder presentations, which are a common emergency presentation to our institution. Acute gallbladder presentations comprise either patients with clinical and radiological evidence of acute cholecystitis or those with persistent biliary colic. A strong body of evidence has shown that early cholecystectomy is a more cost effective approach than delayed cholecystectomy as it reduces the length of hospital stay and lowers morbidity rates.12–14 The aim of the present study was therefore to determine whether the ASM provided better outcomes for patients with acute gallbladder symptoms, compared with the traditional emergency surgery model of care.

Methods

A retrospective review was carried out of all public patients who were admitted for management of acute cholecystitis or persistent biliary colic over a two-year period (1 July 2010 – 30 June 2012) at MMC. This included the one-year period before and one year after the establishment of the ASU on 18 July 2011 at our centre. The study was approved by the Monash Health human research ethics committee as a quality assurance study.

Patients included in the study were diagnosed with an acute gallbladder by correlating history and physical examination findings, with confirmation by ultrasonography showing the presence of gallstones, with or without a thickened gallbladder wall, and/or pericholecystic fluid (cholecystitis vs biliary colic). Patients who were managed conservatively (for many reasons but mainly high anaesthetic risk or concurrent illness that precluded the patient from surgery) were excluded from the final analysis. Patients with gallstone pancreatitis were also treated as a separate category as they were expected to have a different clinical course and length of hospital stay. Independent analysis of their outcome measures was also performed to provide more insight into our management of complicated gallstone disease.

The patient database was anonymised. Patients with acute gallbladder were divided into two groups: those who were admitted prior to 18 July 2011 (pre-ASU group) and those admitted after 18 July 2011 (ASU group). Surgery was performed if the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis or persistent biliary colic was made and if patients were fit for anaesthesia.

Outcome measures included time from presentation to operation, length of stay, length of operating time, number of after-hours operations, conversion to open cholecystectomy and surgical complications. The surgical complications assessed and compared were the incidence of postoperative infection, bile leak and bile duct injury.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS® version 22 (IBM, New York, US). Categorical variables were analysed with Pearson’s chi-squared test. Continuous variables were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 412 consecutive public patients were admitted with acute gallbladder symptoms (acute cholecystitis or persistent biliary colic) through our emergency department over the 2-year study period. There was equal distribution of patients for the pre-ASU and ASU groups. The mean age was 53.1 years (range: 18–101 years) in the pre-ASU cohort and 54.5 years (range: 16–95 years) in the ASU cohort. The patients were predominantly female in both groups (about 60% of the study population). Table 1 shows the patient demographics.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Demographics | Before ASU(n=206) | After ASU (n=206) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age in yrs | 53.1 (range: 18–101) | 54.5 (range: 16–95) |

| Female | 124 (60.2%) | 132 (64.1%) |

| Gallstone pancreatitis | 16 (7.7%) | 28 (13.6%) |

| Managed conservatively | 11 (5.3%) Mean age: 62.4 yrs |

15 (7.3%) Mean age: 75.3 yrs |

ASU = acute surgical unit

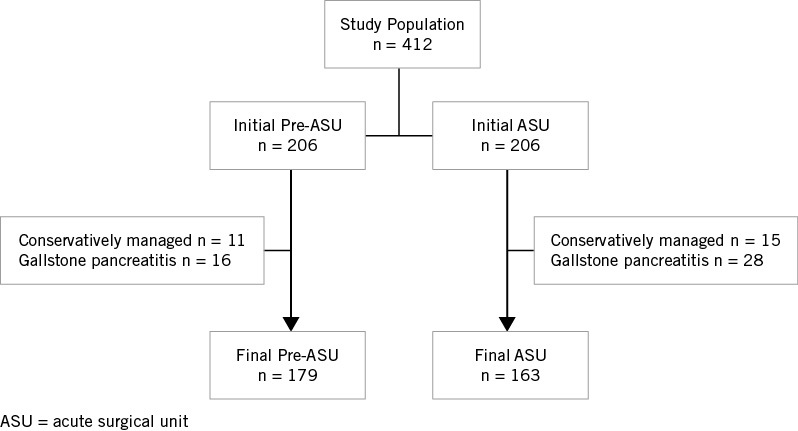

Twenty-six patients (6%) were excluded from the study as they were treated conservatively. There was an overall higher mean age of patients in this subgroup (62.4 years and 75.3 years in the pre-ASU and ASU groups respectively) than in the study population. The main reason for conservative management was anaesthetic risk secondary to co-morbidity. One patient was excluded in her third trimester of pregnancy and two patients refused surgery. In addition, 44 patients (11%) were excluded from the study as they presented with gallstone pancreatitis. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of the study population and reasons for exclusion.

Figure 1.

Distribution of study population with exclusion criteria

A combined total of 342 public patients who presented as an emergency with acute cholecystitis or biliary colic were managed surgically. Of these, 179 patients (52%) were in the pre-ASU group and 163 (48%) in the ASU group. These included 33 (18.5%) with concurrent choledocholithiasis out of the 179 patients in the pre-ASU cohort and 40 (24.5%) out of the 163 patients in the ASU cohort. The presence of choledocholithiasis was diagnosed with preoperative imaging or intraoperative cholangiography. Management of choledocholithiasis included either intraoperative transcystic exploration in its various forms or choledochotomy. Failing that, postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed. The median time to operation was significantly reduced in the ASU group (32.4 vs 25.4 hours, p=0.027).

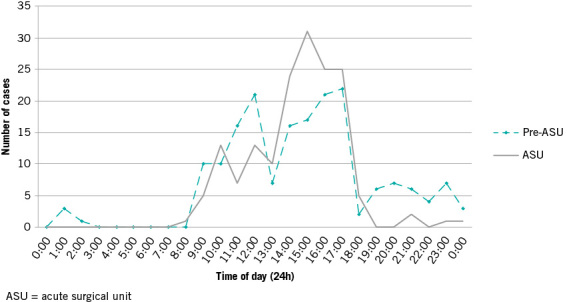

The proportion of operations performed after hours (6pm – 8am) was significantly reduced in the ASU group (19.5% vs 2.5%, p<0.001). This equates to a relative risk reduction of 87.4%. The proportion of procedures commenced during daylight hours was up to 97.5% in the ASU patients, compared with 80.4% in the pre-ASU cohort. Figure 2 shows the number of operations performed at particular times of the day.

Figure 2.

Number of operations at particular hours of the day

The median length of stay was also significantly reduced in the ASU group (4 vs 3 days, p=0.004). The median operating time as well as the rates of conversion to open cholecystectomy, wound infection, bile leak and bile duct injury remained similar over the two-year period. Table 2 summaries these primary outcome measures in patients with gallbladder presentation in both the pre-ASU and ASU groups. Table 3 shows the different histopathological diagnosis of patients who underwent cholecystectomy.

Table 2.

Outcome measures in patients with acute gallbladder presentation

| Outcome measures | Before ASU (n=179) | After ASU (n=163) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median time to operation in hrs | 32.4 (IQR: 18.6–55.7) | 25.2 (IQR: 18.4–40.0) | 0.027* |

| Median operating time in mins | 80 (IQR: 60–110) | 80 (IQR: 60–100) | 0.806* |

| Median length of stay in days | 4 (IQR: 3–6) | 3 (IQR: 2–5) | 0.004* |

| Time of operation | <0.001 ** | ||

| 8am – 6pm | 144 (80.4%) | 159 (97.5%) | |

| 6pm – midnight | 33 (18.4%) | 4 (2.5%) | |

| Midnight – 8am | 2 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Conversion to open procedure | 6 (3.4%) | 10 (6.1%) | 0.224** |

| Bile leak | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.711** |

| Bile duct injury | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.588** |

| Wound infection | 4 (2.2%) | 7 (4.3%) | 0.596** |

ASU = acute surgical unit; IQR = interquartile range

*Mann–Whitney U test; **Pearson’s chi-squared test

Table 3.

Histopathology diagnosis for both patient groups

| Histopathology | Before ASU (n=179) | After ASU (n=163) |

|---|---|---|

| Acute cholecystitis | 27 (15.1%) | 9 (5.5%) |

| Acute-on-chronic cholecystitis | 46 (25.7%) | 39 (23.9%) |

| Adenocarcinoma of gallbladder | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.2%) |

| Chronic cholecystitis | 88 (49.2%) | 98 (60.1%) |

| Cholelithiasis | 1 (0.56%) | 2 (1.2%) |

| Eosinophilic cholecystitis | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.2%) |

| Gangrenous cholecystitis | 16 (8.9%) | 11 (6.7%) |

| No record available | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) |

ASU = acute surgical unit

The ASU group had almost double the number of patients with gallstone pancreatitis compared with the pre-ASU group. The mean age of these patients was 53.5 years (range: 20–88 years) in the pre-ASU cohort and 60.5 years (range: 19–86 years) in the ASU cohort. The median time to operation was reduced for ASU patients (93.8 vs 52.1 hours, p<0.001), as was the median operating time (95 vs 75 minutes, p=0.003). The median length of stay was also reduced in the ASU group (6.5 vs 5 days, p=0.007). There was no significant difference in the number of operations performed after hours (6pm – 8am). The rates of conversion to open cholecystectomy, wound infection, bile leak and bile duct injury also remained similar over the two-year period in patients with gallstone pancreatitis. Table 4 summarises the outcome measures in this subset of patients.

Table 4.

Outcome measures in patients with gallstone pancreatitis

| Outcome measures | Before ASU (n=16) | After ASU (n=28) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median time to operation in hrs | 93.8 (IQR: 49.0–123.5) | 52.1 (IQR: 30.0–82.2) | <0.001* |

| Median operating time in mins | 95 (IQR: 65–125) | 75 (IQR: 60–100) | 0.003* |

| Median length of stay in days | 6.5 (IQR: 5–9.5) | 5 (IQR: 3–9) | 0.007* |

| Time of operation | 0.801** | ||

| 8am – 6pm | 16 (100.0%) | 27 (96.4%) | |

| 6pm – midnight | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.6%) | |

| Midnight – 8am | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Conversion to open procedure | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000** |

| Bile leak | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000** |

| Bile duct injury | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000** |

| Wound infection | 0 (0%) | 2 (7.1%) | 0.601** |

ASU = acute surgical unit; IQR = interquartile range

*Mann–Whitney U test; **Pearson’s chi-squared test

Discussion

Introduction of the ASU at our institution has resulted in several improvements in outcomes for patients who were admitted and underwent early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis or biliary colic. There was a significantly shorter time to operation, a reduction in the number of procedures performed after hours and a decreased length of stay in the ASU group. In addition, our study did not find any statistically significant difference in the rates of conversion to open cholecystectomy. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the rates of postoperative infection, bile leak or bile duct injury.

The implementation of the ASU saw a significant seven-hour decrease in the median time to operation for patients with acute gallbladder presentation. The dedicated ASU team and the availability of the ASU afternoon theatre six days a week resulted in a more targeted and efficient approach to the acute gallbladder, and is a plausible reason for the improvement. The shorter time to cholecystectomy may contribute to the reduced length of stay and the continually low postoperative complication rate, coinciding with findings from the literature. Since the ASU was established, the median length of stay has decreased from four days to three.

Having a dedicated consultant-led team could have led to improvements in the clinical decision making and therefore also the flow of patient care. Patients can be assessed and managed throughout the day with better continuity of care. These findings were significant even in the more varied demographic of cholecystitis patients when compared with our previous study on appendicitis patients.11

Our current study’s most significant result was the reduction in procedures performed after hours (6am – 8am). The ASU saw an 87% reduction in the number of procedures performed after hours compared with the pre-ASU group. Once again, the dedicated ASU theatre and the onsite availability of a consultant were the likely cause of this decrease. The rostered surgeon removed the need for an on-call consultant to return to the hospital to operate after hours. Furthermore, the dedicated ASU theatre helped to ensure theatre availability. This has reinforced our previous findings on appendicectomy patients, namely that the ASU model significantly reduces the number of operations performed after hours.11

Our institution’s general low postoperative infection rate is possibly due to the low number of conversions to open cholecystectomy, which is a known risk for surgical site infection. With no significant difference in the number of conversions to open cholecystectomy, there was also no significant difference in the postoperative infection rates between the pre-ASU and ASU groups. The relatively short overall time to operation may have contributed to the low complication rate. This highlights the need for prompt treatment of patients who present with persistent biliary colic and clinical cholecystitis even though they may not have imaging evidence of cholecystitis. This probably correlates with the higher preponderance of acute-on-chronic cholecystitis and chronic cholecystitis in our histopathology findings (Table 3).

Patients with gallstone pancreatitis were analysed as a different subset of patients. They are expected to have a longer length of stay. This is to ensure resolution of pancreatitis but also allows adequate biliary tract imaging to be performed prior to cholecystectomy. We generally perform cholecystectomy during the index admission to prevent the possibility of recurrence of symptoms and re-presentation while awaiting elective cholecystectomy. In our study, the small sample population of patients with gallstone pancreatitis limits the statistical significance.

This study is also limited by its retrospective nature. Long-term prospective analysis is underway of the impact of the ASU on the management of gallstones in general and its effect on the rate of elective cholecystectomies. A longer period of review of the ASU may also be beneficial to reveal any further avenues for optimisation of the service. Further in-depth study is also needed to determine whether the ASU model has any significant impact on hospital cost savings.

Conclusions

In the setting of acute gallbladder presentation, this study has found that the ASM is a more effective model of care, with significant improvement in objective measures without exacerbating surgical complications.

References

- 1.Earley AS, Pryor JP, Kim PK. et al. An acute care surgery model improves outcomes in patients with appendicitis. Ann Surg 2006; : 498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekeh AP, Monson B, Wozniak CJ. et al. Management of acute appendicitis by an acute care surgery service: is operative intervention timely? J Am Coll Surg 2008; : 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parasyn AD, Truskett PG, Bennett M. et al. Acute-care surgical service: a change in culture. ANZ J Surg 2009; : 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehane CW, Jootun RN, Bennett M. et al. Does an acute care surgical model improve the management and outcome of acute cholecystitis? ANZ J Surg 2010; : 438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox MR, Cook L, Dobson J. et al. Acute Surgical Unit: a new model of care. ANZ J Surg 2010; : 419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gandy RC, Truskett PG, Wong SW. et al. Outcomes of appendicectomy in an acute care surgery model. Med J Aust 2010; : 281–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Von Conrady D, Hamza S, Weber D. et al. The acute surgical unit: improving emergency care. ANZ J Surg 2010; : 933–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau B, Difronzo LA. An acute care surgery model improves timeliness of care and reduces hospital stay for patients with acute cholecystitis. Am Surg 2011; : 1,318–1,321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page DE, Dooreemeah D, Thiruchelvam D. Acute surgical unit: the Australasian experience. ANZ J Surg 2014; : 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baggoley C, Owler B, Grigg M. et al. Expert Panel Review of Elective Surgery and Emergency Access Targets under the National Partnership Agreement on improving Public Hospital Services. Canberra: Australian Government; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poh BR, Cashin P, Dubrava Z. et al. Impact of an acute surgery model of appendicectomy outcomes. ANZ J Surg 2013; : 735–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai PB, Kwong KH, Leung KL. et al. Randomized trial of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg 1998; : 764–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo C, Liu C, Fan S. et al. Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg 1998; : 461–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keus F, de Jong JA, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; : CD006231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]