Abstract

Introduction

Primary hyperparathyroidism (pHPT) is usually the result of a single adenoma that can often be accurately located preoperatively and excised by a focused operation. Intraoperative parathyroid hormone (IOPTH) measurement is used occasionally to detect additional abnormal glands. However, it remains controversial as to whether IOPTH monitoring is necessary. This study presents the results of a large series of focused parathyroidectomy without IOPTH measurement.

Methods

Data from 2003 to 2014 were collected on 180 consecutive patients who underwent surgical treatment for pHPT by a single surgeon. Preoperative ultrasonography and sestamibi imaging was performed routinely, with computed tomography (CT) and/or selective venous sampling in selected cases. The preferred procedure for single gland disease was a focused lateral approach guided by on-table surgeon performed ultrasonography. Frozen section was used selectively and surgical cure was defined as normocalcaemia at the six-month follow-up appointment.

Results

Focused surgery was undertaken in 146 patients (81%) and 97% of these cases had concordant results with two imaging modalities. In all cases, an abnormal gland was discovered at the predetermined site. Of the 146 patients, 132 underwent a focused lateral approach (11 of which were converted to a collar incision), 10 required a collar incision and 4 underwent a mini-sternotomy. At 6 months following surgery, 142 patients were normocalcaemic (97% primary cure rate). Three of the four treatment failures had subsequent surgery and are now biochemically cured. There were no complications or cases of persistent hypocalcaemia.

Conclusions

This study provides further evidence that in the presence of concordant preoperative imaging, IOPTH measurement can be safely omitted when performing focused parathyroidectomy for most cases of pHPT.

Keywords: Intraoperative monitoring, Parathyroidectomy, Parathyroid hormone

Parathyroidectomy is the established treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism (pHPT), relieving symptoms of hypercalcaemia while also preventing renal and skeletal complications.1,2 Approximately 85% of cases of pHPT are due to the presence of a single adenomatous gland with the remaining cases secondary to multigland disease and, rarely, parathyroid cancer.3

The traditional operative approach involved visualisation of all four parathyroid glands via a ‘collar’ incision and excision of the enlarged glands. However, the availability of increasingly accurate preoperative imaging techniques, including technetium sestamibi scintigraphy and cervical ultrasonography, have enabled the clinician to locate the site of the culprit adenomatous gland accurately.4 The high reliability of these imaging modalities has led to parathyroidectomy becoming a focused procedure. Single gland excision is now the accepted gold standard technique. This is most frequently performed by a limited, laterally placed incision (termed minimal incision parathyroidectomy) in contrast to the collar incision. A mini-incision affords several benefits including simplicity, reduced costs, improved patient satisfaction and reduced operative time.5 Furthermore, cure rates are reported to be equivalent to the traditional four-gland exploration technique.6

Technetium sestamibi imaging has a quoted sensitivity of 88% in localising a single parathyroid adenoma, with ultrasonography reported as being 71–80% sensitive.7 Nevertheless, when both investigations are concordant, the sensitivity of identifying a single adenoma correctly rises to 94%.8 Despite the accuracy of these investigations, many endocrine surgeons advocate the routine use of intraoperative parathyroid hormone (IOPTH) measurement as a further safeguard to confirm excision of all abnormal parathyroid glands.9

Proponents of the routine use of IOPTH levels cite the potential for improving the primary cure rates in focused parathyroidectomy. However, debate persists as to whether there is evidence to support this argument.10 IOPTH monitoring adds financial cost and can be associated with false negative results (occurring when the PTH level does not fall despite removal of the only abnormal gland) that lead to unnecessary and potentially harmful neck exploration. Furthermore, false positive results have been reported that suggest surgical cure but the postoperative calcium level remains elevated, signifying residual disease. Our study of the experience of a single surgeon working in a district general hospital reports a large series of focused parathyroidectomy performed without the use of IOPTH measurement.

Methods

Data were collected between October 2003 and December 2014 from 180 consecutive patients who underwent surgical treatment for pHPT. The median patient age was 50 years (range: 16–91 years). Overall, 179 patients underwent preoperative imaging with sestamibi and ultrasonography. The remaining patient was in the second trimester of pregnancy and had ultrasonography only.

When both the sestamibi imaging and ultrasonography were concordant, the patient proceeded to single gland excision in a focused operation. If the sestamibi imaging was positive but ultrasonography negative, the patient underwent computed tomography (CT). CT confirmation of an enlarged parathyroid gland at the site of the increased sestamibi uptake led to a focused approach.

From 2003 to 2011, if both sestamibi imaging and ultrasonography were negative (or equivocal), the patient underwent four-gland parathyroid exploration via a collar incision. In January 2012, the senior author joined a regional multidisciplinary endocrinology team. Subsequently, patients with negative sestamibi imaging and ultrasonography were investigated further with CT and/or selective venous sampling in a more determined attempt to locate the culprit adenoma.

Surgical cure was defined as a normal serum calcium level (2.2–2.6mmol/l) six months following the operation.

Surgical approach

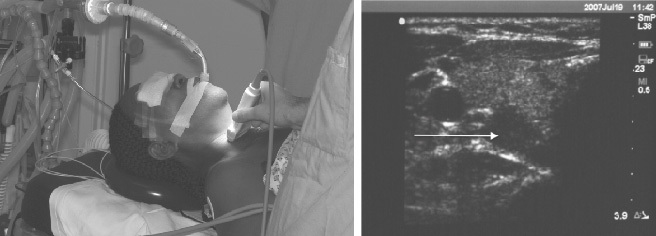

When a single adenoma was identified in the neck, the preferred procedure was a focused lateral approach (FLA) via a 2–3cm incision. From 2006, the senior author performed on-table portable ultrasonography to visualise the adenoma and mark the site of the incision (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

On-table ultrasonography performed by the operating surgeon to locate the adenoma and mark the skin incision site for a focused lateral approach

The FLA is a simple technique that initially involves lateral retraction of the sternomastoid muscle with medial retraction of the strap muscles. The common carotid artery and the lateral aspect of the thyroid lobe are identified, and the pretracheal fascia between these structures is divided. With gentle retraction, the parathyroid adenoma can be quickly identified and excised.

For some large adenomas and for centrally placed superficial glands, a small collar incision was preferred. Once the abnormal gland was excised, the operation was concluded and no attempt was made to identify the remaining gland on that side of the neck. A frozen section examination was used selectively to confirm excision of parathyroid tissue.

A FLA was not possible in cases of mediastinal adenomas, which were excised via a limited sternotomy. In cases with negative imaging, a four-gland parathyroid exploration was performed via a collar incision.

Results

Of the 180 patients, 122 had positive and concordant sestamibi imaging and ultrasonography, identifying a single adenoma in the neck. In seven cases, sestamibi imaging was positive while ultrasonography was negative; CT was then successful in locating a culprit lesion. In six cases, an adenoma was located with ultrasonography and selective venous sampling. Four further patients were considered suitable for a focused approach based on positive ultrasonography (n=2) and positive sestamibi imaging (n=2). These cases occurred early in the patient series and prior to the surgeon joining a regional multidisciplinary endocrinology team. Three patients had positive ultrasonography and CT. In four cases, a single mediastinal adenoma was identified by sestamibi imaging plus CT (n=3) and CT plus selective venous sampling (n=1).

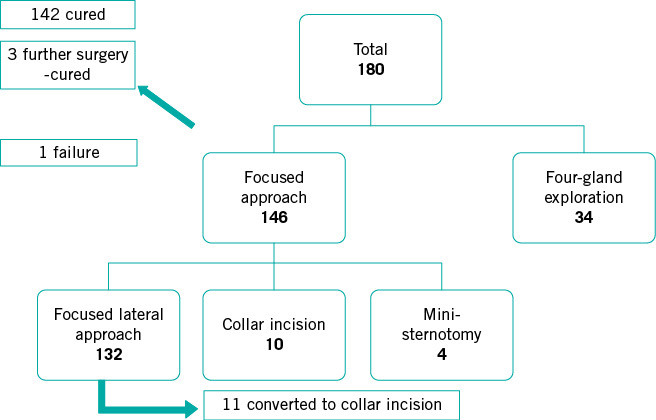

Focused surgery was undertaken subsequently in 142 patients with concordant preoperative localisation. An additional four patients, mentioned above, also underwent focused surgery despite positive imaging on only one imaging modality. A total of 146 patients therefore had an adenoma localised preoperatively and underwent a focused operation. The remaining 34 patients underwent 4-gland exploration (Fig 2). In all patients undergoing a focused approach, an enlarged parathyroid gland was located at the exact site identified by preoperative imaging.

Figure 2.

Summary of the results

In those patients undergoing single gland excision, 142 (97%) were cured with the primary procedure. Three of the four treatment failures had a successful subsequent operation to excise a second adenoma. The remaining patient has been diagnosed with multiple endocrine neoplasia and is being managed conservatively. In 11 of the patients who underwent a FLA, it was necessary to convert to a collar incision to safely excise either large glands or atypical glands adherent to the thyroid capsule.

Of the 34 patients who underwent 4-gland exploration, 30 (88%) were cured with a primary operation. The pathology in those who remain hypercalcaemic is multigland hyperplasia (n=2), parathyroid cancer (n=1) and a probable missed second adenoma (n=1). These patients have relatively low serum calcium levels and are being managed conservatively. Overall, 172 (96%) of the 180 patients were cured with primary surgery. There were no nerve injuries or major complications in this series. One patient who had a four-gland exploration requires long-term calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that sestamibi imaging in conjunction with ultrasonography can locate many parathyroid adenomas reliably, allowing focused surgical excision. Our primary cure rate (97%) is equivalent to the reported outcomes of focused parathyroidectomy performed with routine IOPTH measurement.11,12 The favourable results from this series add further evidence to the tenet that routine IOPTH monitoring provides little benefit in focused parathyroidectomy.

Access to accurate localisation imaging has been key to the high cure rates achieved in this series. Expertise in ultrasonography combined with the high specificity of sestamibi imaging in the detection of an anatomical abnormality provides strong evidence for the presence of an adenoma. Reproducing these results in other centres would therefore be dependent on similar access to imaging and a multidisciplinary endocrinology team for non-concordant cases.

A major drawback of IOPTH monitoring is the associated financial costs. Reported estimates vary, with Morris et al stating an additional cost of £310 per case.13 This was inclusive of the assay, the analyser and a dedicated technician. In addition, IOPTH measurement extends the operative time. It requires approximately 15 minutes to obtain an IOPTH reading and with the currently preferred IOPTH protocols, the additional time spent in the operating theatre will average approximately 30 minutes.

IOPTH measurement has a reported sensitivity of 58% in detecting further adenomas in cases of multiple gland disease.14 This relatively low figure suggests that while IOPTH is helpful in confirming single gland disease, it does not offer complete protection against missing additional abnormal glands. IOPTH measurement may produce both false positive and false negative results. A false positive result may occur when the additional adenoma is significantly smaller than the dominant excised gland. Consequently, the function of the smaller gland has been relatively suppressed and it may only begin to secrete high levels of PTH several weeks following the operation.15 In such cases, IOPTH would register an inappropriate ‘drop’, providing false reassurance to the surgeon. Haemolysis of the PTH sample may also contribute to false positive measurements.16

False negative rates in IOPTH measurement can reach 9% when sampling ten minutes after excision.17 The delay in the fall in PTH levels may be attributed to the natural variability in the half-life or to reduced glomerular clearance in the presence of coexisting renal impairment. As a consequence of a false negative result, the surgeon may proceed to a futile neck exploration, which increases the operative time and subjects the patient to unnecessary risk.18 The fact that several protocols are used to quantify an adequate drop in PTH reflects a lack of consensus among surgeons on how best to interpret the IOPTH results.19,20

Several series of parathyroidectomy have been reported without the use of IOPTH measurement. Haciyanli et al found success with a similar approach to ours in a series of 47 patients21 and Sakimura et al reported their experience of 60 patients.22 Our experience of 180 cases represents a large series of patients providing further evidence that IOPTH measurement can be safely excluded from focused parathyroidectomy.

Proponents of IOPTH monitoring cite its value in selected cases where there is suspicion of multigland disease and there is no doubt that it may assist the surgeon during four-gland exploration. However, we contend that biochemically confirmed hyperparathyroidism plus concordance with two imaging modalities is a sufficient basis for the focused approach without including IOPTH measurement. Kebebew et al described a scoring system using preoperative biochemistry and imaging that reliably distinguished single and multiple gland disease. Their data indicate that patients with concordant imaging for single gland disease can safely undergo focused surgery without the need for IOPTH monitoring.23

A small number of patients are not cured by a primary procedure and this is reflected in all published series of parathyroidectomy. Fortunately, those not cured by the primary procedure can undergo further investigation and proceed to a second procedure with a high chance of cure. The FLA described is our preferred technique for excising single glands. This approach involves minimal dissection and leaves little scar tissue. Three of our four patients who remained hypercalcaemic have been cured with a subsequent four-gland exploration and the original operation did not noticeably hinder the surgical dissection or place the recurrent laryngeal nerve at an increased risk.

Conclusions

This study has shown that high cure rates of pHPT can be obtained using focused surgery without IOPTH measurement. These outcomes are critically dependent on the quality of the preoperative imaging and we would stress the importance of concordant imaging before undertaking a focused approach. IOPTH monitoring may provide additional reassurance to the operating surgeon but it leads to increased financial costs, longer operative times and unnecessary further exploration when false negative results are obtained. The results from this series indicate that IOPTH measurement can be safely omitted from the operative protocol of focused parathyroidectomy.

Acknowledgements

The material in this paper was presented at the International Surgical Congress of the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland held in Harrogate, April 2014.

References

- 1.Espiritu RP, Kearns AE, Vickers KS. et al. Depression in primary hyperparathyroidism: prevalence and benefit of surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; : E1737–E1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dy BM, Grant CS, Wermers RA. et al. Changes in bone mineral density after surgical intervention for primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery 2012; : 1,051–1,058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohebati A, Shaha AR. Imaging techniques in parathyroid surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism. Am J Otolaryngol 2012; : 457–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gracie D, Hussain SS. Use of minimally invasive parathyroidectomy techniques in sporadic primary hyperparathyroidism: systematic review. J Laryngol Otol 2012; : 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunstman JW, Udelsman R. Superiority of minimally invasive parathyroidectomy. Adv Surg 2012; : 171–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slepavicius A, Beisa V, Janusonis V, Strupas K. Focused versus conventional parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism: a prospective, randomized, blinded trial. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008; : 659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siperstein A, Berber E, Barbosa GF. et al. Predicting the success of limited exploration for primary hyperparathyroidism using ultrasound, sestamibi, and intraoperative parathyroid hormone: analysis of 1158 cases. Ann Surg 2008; : 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carneiro-Pla DM, Solorzano CC, Irvin GL. Consequences of targeted parathyroidectomy guided by localization studies without intraoperative parathyroid hormone monitoring. J Am Coll Surg 2006; : 715–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider DF, Mazeh H, Chen H, Sippel RS. Predictors of recurrence in primary hyperparathyroidism: an analysis of 1386 cases. Ann Surg 2014; : 563–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mihai R, Palazzo FF, Gleeson FV, Sadler GP. Minimally invasive parathyroidectomy without intraoperative parathyroid hormone monitoring in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Br J Surg 2007; : 42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udelsman R. Six hundred fifty-six consecutive explorations for primary hyperparathyroidism. Ann Surg 2002; : 665–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Pruhs Z, Starling JR, Mack E. Intraoperative parathyroid hormone testing improves cure rates in patients undergoing minimally invasive parathyroidectomy. Surgery 2005; : 583–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris LF, Zanocco K, Ituarte PH. et al. The value of intraoperative parathyroid hormone monitoring in localized primary hyperparathyroidism: a cost analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; : 679–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miura D, Wada N, Arici C. et al. Does intraoperative quick parathyroid hormone assay improve the results of parathyroidectomy? World J Surg 2002; : 926–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sitges-Serra A, Díaz-Aguirregoitia FJ, de la Quintana A. et al. Weight difference between double parathyroid adenomas is the cause of false-positive IOPTH test after resection of the first lesion. World J Surg 2010; : 1,337–1,342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moalem J, Ruan DT, Farkas RL. et al. Hemolysis falsely decreases intraoperative parathyroid hormone levels. Am J Surg 2009; : 222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stalberg P, Sidhu S, Sywak M. et al. Intraoperative parathyroid hormone measurement during minimally invasive parathyroidectomy: does it ‘value-add’ to decision-making? J Am Coll Surg 2006; : 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Opoku-Boateng A, Bolton JS, Corsetti R. et al. Use of a sestamibi-only approach to routine minimally invasive parathyroidectomy. Am Surg 2013; : 797–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riss P, Kaczirek K, Heinz G. et al. A ‘defined baseline’ in PTH monitoring increases surgical success in patients with multiple gland disease. Surgery 2007; : 398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barczynski M, Konturek A, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A. et al. Evaluation of Halle, Miami, Rome, and Vienna intraoperative iPTH assay criteria in guiding minimally invasive parathyroidectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2009; : 843–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haciyanli M, Genc H, Damburaci N. et al. Minimally invasive focused parathyroidectomy without using intraoperative parathyroid hormone monitoring or gamma probe. J Postgrad Med 2009; : 242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakimura C, Minami S, Hayashida N. et al. Can the use of intraoperative intact parathyroid hormone monitoring be abandoned in patients with hyperparathyroidism? Am J Surg 2013; : 574–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kebebew E, Hwang J, Reiff E. et al. Predictors of single-gland vs multigland parathyroid disease in primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch Surg 2006; : 777–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]