Abstract

Introduction

This study reviews the litigation costs of avoidable errors in orthopaedic operating theatres (OOTs) in England and Wales from 1995 to 2010 using the National Health Service Litigation Authority Database.

Materials and methods

Litigation specifically against non-technical errors (NTEs) in OOTs and issues regarding obtaining adequate consent was identified and analysed for the year of incident, compensation fee, cost of legal defence, and likelihood of compensation.

Results

There were 550 claims relating to consent and NTEs in OOTs. Negligence was related to consent (n=126), wrong-site surgery (104), injuries in the OOT (54), foreign body left in situ (54), diathermy and skin-preparation burns (54), operator error (40), incorrect equipment (25), medication errors (15) and tourniquet injuries (10). Mean cost per claim was £40,322. Cumulative cost for all cases was £20 million. Wrong-site surgery was error that elicited the most successful litigation (89% of cases). Litigation relating to implantation of an incorrect prosthesis (eg right-sided prosthesis in a left knee) cost £2.9 million. Prevalence of litigation against NTEs has declined since 2007.

Conclusions

Improved patient-safety strategies such as the World Health Organization Surgical Checklist may be responsible for the recent reduction in prevalence of litigation for NTEs. However, addition of a specific feature in orthopaedic surgery, an ‘implant time-out’ could translate into a cost benefit for National Health Service hospital trusts and improve patient safety.

Keywords: Litigation, Patient safety, Orthopaedic, Negligence, Consent; Wrong-site surgery

Litigation in orthopaedic surgery is becoming more common in the UK and worldwide.1 Combined cost of orthopaedic litigation from 2000 to 2006 in England has been estimated at £193,944,167 ($321,695,070).1 Compensation for proven negligence is awarded on the basis of pain, suffering, loss of amenity, and financial losses to the claimant.

In general, it is accepted that successful litigation occurs for intraoperative errors (eg median-nerve palsy after decompression of the carpal tunnel). However, other forms of error and misjudgment can also contribute. The aim of the present study was to assess the implications of ‘non-technical’ errors (NTEs).

We defined a NTE as ‘an avoidable incident that occurred due to a failure of patient safety, and which was not a recognised complication of the intended surgery’. NTEs are not due to a failure of clinical judgement or expertise. NTEs in the operating theatre and faults in obtaining adequate consent are readily avoidable and often originate from deficiencies in communication.2

Patient safety in the operating theatre is the responsibility of the surgical team. However, the consultant surgeon is the most likely person to find himself/herself the subject of litigation. The World Health Organisation Surgical Checklist (WSC; Table 1) is a perioperative tool (a team-based, patient-oriented set of questions) to help reduce the prevalence of intraoperative NTEs.

Table 1.

World Health Organization Surgical Checklist8

| Before induction of anaesthesia | Before the incision | Before the patient leaves theatre |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

We reviewed the litigation costs of potentially avoidable errors in orthopaedic operating theatres (OOTs) in England and Wales from 1995 to 2010. The primary aim was to identify trends in claims for NTEs, and review the impact of the WSC on litigation claims.

Methods

Data for litigation for all cases related to orthopaedic and trauma surgery were obtained from the National Health Service Litigation Authority Database (NHSLAD) under the Freedom of Information Act, and was current until its extraction in July 2013. The NHSLAD provides information on the year of the incident, creation of the claim, compensation awarded, overall costs to the National Health Service (NHS), the clinical environment of the alleged negligence, and a short descriptive narrative of the claim.

Litigation specifically against NTEs in the OOT and consenting issues were identified through analyses of the claimant narrative in the NHSLAD. Unsettled claims were recorded to identify trends in current claims but were excluded from cost analyses because data were not available. A relatively large proportion of claims after 2010 remain unsettled. Therefore, the dataset for analyses was from 1995 to 2010.

Claims were grouped according to those relating to consent and perioperative safety issues. Alleged errors in the OOT were grouped according to the nature of the claim. Wrong-site surgery (WSS), retained instruments, and injuries sustained in the OOT were sub-classified. The year of incident, year of the claim, compensation fee, cost of legal defense, and likelihood of compensation were analysed.

Results

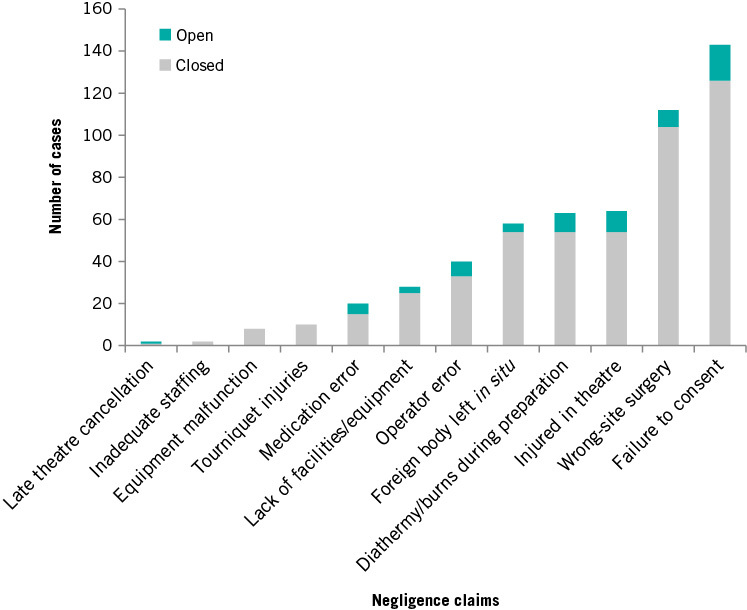

There were 550 claims relating to obtaining consent and NTEs in the OOT out of 9,865 types of negligence claims relating to orthopaedic surgery. There were 64 unsettled claims. Unsettled claims were excluded from cost calculations, leaving 486 closed cases for cost analyses. Claims for negligence related to alleged failures to obtain appropriate consent (n=126, 25.9%) and NTEs (360, 74.1%) are shown in Fig 1.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of alleged negligence cases relating to orthopaedic surgery between 1995 and 2010 in England and Wales

Anatomical sites of surgery were: foot and ankle (n=85, 15.4%), lower limb (224, 40.7%), hand (58, 10.5%), upper limb (52, 9.5%), spine (47, 8.5%) and unknown site (83, 15.1%). Usually, unknown site/subspecialty was related to general claims such as errors related to medication, burns, and anaesthesia.

The clinical setting of alleged negligence was not recorded routinely. Our interpretation was that 259 errors were in elective cases, and 69 occurred in the trauma setting. We were unable to determine the setting for the other 221 cases.

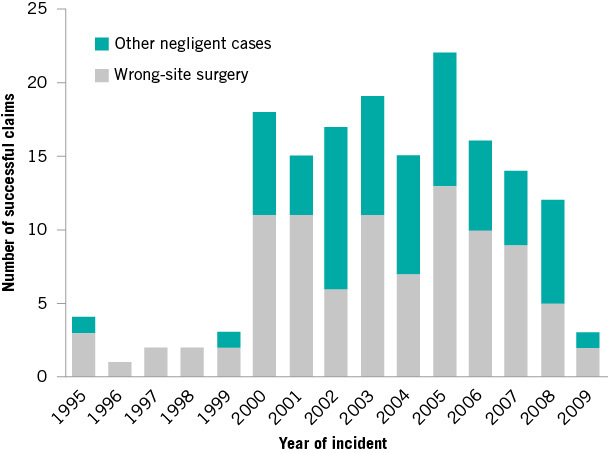

Prevalence of successful claims was 6 in 1995, peaked at 45 in 2005, and declined to 3 in 2009 (though 5 claims remain unsettled) (Figure 2). Mean difference between the year of the alleged incident and creation of the claim was 1.9 (median, 1; interquartile range (IQR), 1–3; range, 0–13) years.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of wrong-site surgery and other non-technical errors relating to insufficient adherence to the World Health Organization Surgical Checklist

Issues with consent were the most common source of litigation (n=126 of closed cases). This group included operating without any consent at all and a failure to obtain written informed consent. Claims relating to a failure to gain written informed consent were reported in a vague manner in the NHSLAD. It would appear that the subjective nature of these claims is reflected in the relatively low prevalence of proven negligence because only 52% of cases resulted in compensation.

WSS (including ‘wrong procedure’) occurred in 111 cases: spinal level (n=23), hands (27), feet (16), limbs (41) and unknown site (4). WSS was the error that resulted in the most successful litigation (89% of cases) (Table 2). Reasons for uncompensated claims for WSS were not reported in the NHSLAD.

Table 2.

Likelihood of successful claims and subsequent cost analysis according to group

| Closed claims | Percentage compensated | Mean compensation (£) | Mean defence cost (£) | Mean cost per claim (£) | Sum cost (£) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late theatre cancellation | 1 | 100 | 7,500 | 3,433 | 10,933 | 10,933 |

| Inadequate staffing | 2 | 100 | 7,625 | 9,915 | 17,540 | 35,081 |

| Equipment malfunction | 8 | 63 | 18,220 | 15,884 | 34,104 | 272,835 |

| Tourniquet injuries | 10 | 70 | 41,478 | 34,593 | 76,071 | 760,713 |

| Medication error | 15 | 67 | 20,660 | 12,608 | 33,268 | 499,024 |

| Lack of facilities/equipment | 25 | 92 | 40,824 | 18,448 | 59,272 | 1,481,814 |

| Operator error | 33 | 88 | 83,808 | 21,418 | 105,227 | 3,472,491 |

| Foreign body left in situ | 54 | 46 | 15,482 | 8,607 | 24,089 | 1,300,818 |

| Diathermy/burns during preparation | 54 | 83 | 13,005 | 7,417 | 20,423 | 1,102,852 |

| Injured in operating theatre | 54 | 72 | 8,107 | 8,953 | 17,061 | 904,239 |

| Wrong-site surgery | 104 | 89 | 31,213 | 12,383 | 43,596 | 4,845,736 |

| Failure to obtain adequate consent | 126 | 52 | 23,866 | 18,413 | 42,279 | 5,328,513 |

‘Operator errors’ (eg insertion of right-knee prosthesis into the left knee) appeared to be the most expensive group, with a mean cost of £105,227 (Table 2). However, the median cost was £16,000 because two operator errors cost >£500,000 each. A substantial group of claims (n=24) was related to implantation of an incorrect prosthesis (sum cost, £2.9 million). This error type is relatively specific to orthopaedic surgery, and may not be prevented by adhering to the WSC.

Injuries in the OOT (n=54) were deemed events separate from tourniquet-related harm (10), as well as diathermy and skin-preparation burns (54). These injuries included patients being dropped during bed transfer, accidental lacerations sustained during surgery, trauma to the airway during anaesthesia, traction injuries, and pressure sores.

Twenty-four claims were related to errors in the ‘swabs, needles and instruments count’ at a sum cost of £606,027. Most claims for retained instruments were related to broken hardware that was not retrieved at the index procedure. Claims for broken hardware were not considered to be ‘counting errors’.

WSS and failure to obtain adequate consent were the most costly groups (>£4 million each). The highest payout for any case was £1.8 million (wrong-side knee arthroplasty).

Mean compensation per claim was £26,513 (median, £5,000; IQR, £0–14,522; range, £0–£1.5 million). Mean legal costs were £14,754 (median, £4,515; IQR, £111–15,712; range, £0–£270,000). Cumulative cost for all cases was £20,015,000 from 165 NHS hospital trusts.

Combined cost for all orthopaedic-related litigation claims from 1995 to 2010 in England and Wales was £402,003,300.

Adherence to the WSC could have avoided 229 errors that resulted in a claim (42%) at a combined cost of £8.5 million. These claims included surgery for which consent had not been obtained, lack of prophylactic antibiotics, inadequate sterility of instruments, and WSS.

Discussion

The NHSLAD employed in the present study is one of the largest databases of orthopaedic surgery-based litigation.3 Use of the NHSLAD to analyse avoidable litigation claims relating to perioperative NTEs allows meaningful lessons to be learnt. Awareness of the pitfalls in patient safety to avoid NTEs would save >£18 million in litigation costs.

Highest prevalence of all claims was for inadequacies relating to obtaining consent for a procedure. Our data show that alleged instances of not obtaining adequate consent occurred in 1.3% of all 9,865 litigation claims, in comparison with 5.3% of 1,925 claims in an orthopaedic practice in Italy.4

Failure to obtain adequate consent was also the least likely type of claim to lead to an award of compensation. Nevertheless, it costs the NHS large sums to defend (mean of £18,413 per case). Our data support the use of consent governance in NHS hospital trusts. There are strong arguments to develop ‘procedure-specific consent forms’ for high-volume cases such as decompression of the carpal tunnel, total hip arthroplasty, and total knee arthroplasty to better inform patients and reduce the litigation burden.1,5 Obtaining consent on the ward and in preoperative waiting areas has been shown to increase the risk of litigation compared with obtaining consent in the clinic.6 Dictation of the discussion relating to consent in the clinic letter or operative note is recommended to aid successful defense of malpractice claims.6

The UK National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) has detailed eight core ‘never events’, including WSS and retained instruments, after surgery. More than 120,000 surgical-safety incidents were recorded in England in 2007.7 The WSC, instrument counts, education on patient handling, and consent governance provide opportunities to circumvent these errors. Growing evidence supports a reduction in 30-day morbidity and mortality using the WSC,8 but there is less comparable evidence for WSS and avoidable perioperative mishaps.9 Accurate compliance with the WSC varies worldwide.10,11

The present study appears to demonstrate evidence that the WSC is affecting the prevalence of WSS and perioperative malpractice in England and Wales.

WSS in orthopaedic surgery is the highest of all specialties (1 per 105,712 cases).12Orthopaedic surgery is the fifth most likely specialty in which litigation may be sought.13 Causes of never events are often multifactorial, but near-misses, such as transfer of ink arrows from one marked limb to another, can occur.14

Incidence of WSS to the spine, hands and feet is well recognised.9,12 Incidence of spinal surgeons in North America undertaking wrong-level surgery is 1 in 3,110.15 Incidence of hand surgeons carrying out WSS is 1 in 27,686 cases.16 In general, WSS is considered to be an indefensible error in surgical practice.17 Temporal trends of WSS as shown in Fig 2 demonstrate a sharp increase in litigation in 2000–01 and a decline in 2008–09.

Interestingly, 11% of WSS cases did not receive compensation, but this datum may reflect on the descriptive accuracy of the NHSLAD. Also, litigation claims against clinicians within England and Wales can often be raised with no cost to the patient.

Foreign bodies left in situ demonstrated a low prevalence of compensation (46% of 60 cases) (Table 2). Despite ‘retained instruments’ being described as a core never event by the NPSA, it appears that the clinical decision-making for leaving ‘difficult to obtain’ metalwork and broken tools is reflected in a low prevalence of success of claims. ‘True’ never events, such as retained needles and scalpel blades after arthroscopic knee surgery, occur and these are largely indefensible. Retained surgical instruments are more common in cavity surgery, and are relatively rare in orthopaedic surgery.18 If defending cases where it has been deemed clinically necessary to leave broken tools or hardware in situ, taking intraoperative fluoroscopic images and clearly documenting the clinical problem is advised. Objective negligence claims such as WSS and operator error are more successful and have considerable financial implications.

Inadequate staffing and lack of equipment/facilities are encountered frequently in public-sector healthcare. Cases that went on to be awarded compensation in these groups were related to an abandoned procedure due to unforeseen shortcomings after the initiation of surgery or induction of anaesthesia. The WSC team briefing at the start of the operating list should identify deficiencies in equipment and personnel. Deficiencies are not always avoidable, but they should be identified early and far in advance of the induction of anaesthesia or undertaking of surgery.

At least 47% of litigation based on NTEs occurred in a controlled elective setting. This relatively high proportion may be due to an increased awareness of unknown variables in emergency and trauma surgery, or because it is more difficult to defend avoidable errors in the elective setting.

Anaesthetists also need to be wary in the OOT because nearly £500,000 of cost was attributable to medication errors (eg injection of pure alcohol for a nerve block instead of a local anaesthetic). Two cases of wrong-side nerve blocks were observed in the NHSLAD, and both resulted in successful litigation. One case of WSS was related to an anaesthetist shaving and preparing the wrong leg before knee arthroscopy and cost £8,300.

The recent reduction in litigation claims per year (Figure 2) relating to NTEs may be evidence of increased safety awareness in the OOT and correct application of the WSC: the latter could have saved £8.5 million in litigation claims. However, a mean delay of 1.9 years between the alleged incident and litigation claim weakens the argument of an association between a reduction in the number of NTEs in the OOT with WSC implementation. Patient safety reporting systems (present in all operating theatres) are more likely to support or refute this postulated correlation.7,9

We suggest introduction of an additional and documented ‘implant time-out’ whereby scrub staff and the operating surgeon can formally review the prosthesis before implantation. An implant time-out could have saved £2.9 million in litigation costs, plus considerable expenditure on unnecessarily opened prostheses.

Limitations of our study relate to a database that was not designed for clinical research. As recognised by other studies using the NHSLAD, the quality of descriptive data and case coding may have been suboptimal.19–21

The consultant orthopaedic surgeon is the team leader in the OOT and is held accountable for litigation claims. Skevington et al have described the environmental, systematic, psychological and organisational factors that contribute to consultant surgeons making avoidable errors.22 Such factors must be recognised and reflected upon to avoid errors in the future.

The importance of ‘check-listing’ the surgical procedure in the perioperative period is clear.8,11 The incidence of avoidable (but easily made) clinical errors was seen throughout the NHSLAD. Using mechanisms to reduce the impact of human error in OOTs will translate into clinical and cost benefits.

Conclusion

Avoidable errors in the OOT and litigation claims relating to inadequate consent have considerable cost implications. Our analysis suggests that rigorous implementation of the WSC, with an additional time-out for checking the appropriateness of the chosen orthopaedic implant, could result in important increases in patient safety, and reduce the risk of litigation. Matters relating to obtaining consent are recurring issues, so hospitals must implement rigorous mechanisms for ensuring each patient has adequate, informed consent that covers all of the serious and frequently occurring risks of the procedure.

References

- 1.Atrey A, Gupte CM, Corbett SA. Review of successful litigation against English health trusts in the treatment of adults with orthopaedic pathology: clinical governance lessons learned. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; : e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gawande AA, Zinner MJ, Studdert DM, Brennan TA. Analysis of errors reported by surgeons at three teaching hospitals. Surgery 2003; : 614–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McWilliams AB, Douglas SL, Redmond AC. et al. Litigation after hip and knee replacement in the National Health Service. Bone Joint J 2013; : 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarantino U, Giai Via A, Macrì E, Eramo A, Marino V, Marsella LT. Professional liability in orthopaedics and traumatology in Italy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; : 3,349–3,357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Upadhyay A, York S, Macaulay W. et al. Medical malpractice in hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2007; (6 Suppl 2): 2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya T, Yeon H, Harris MB. The medical-legal aspects of informed consent in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; : 2,395–2,400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Patient Safety Agency. Patient safety data . Available from www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/patient-safety-data/ (accessed 14 September 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haynes A, Weiser T, Berry W. et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 2009; : 491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panesar S, Noble DJ, Mirza SB. et al. Can the surgical checklist reduce the risk of wrong site surgery in orthopaedics? Can the checklist help? Supporting evidence from analysis of a national patient incident reporting system. J Orthop Surg Res 2011; : 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickering S, Robertson E, Griffin D. et al. Compliance and use of the World Health Organization checklist in UK operating theatres. Br J Surg 2013; : 1,664–1,670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connor P, Reddin C, O’Sullivan M, O’Duffy F, Keogh I. Surgical checklists: the human factor. Patient Saf Surg 2013, : 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson PM, Muir LT. Wrong-site surgery in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; : 1,274–1,280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould MT, Langworthy MJ, Santore R, Provencher MT. An analysis of orthopaedic liability in the acute care setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; (): 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crocker M, Norris J. Preoperative skin marking and perioperative checks require careful thought: a report of a near miss. Br J Neurosurg 2012; : 401–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mody MG, Nourbakhsh A, Stahl DL. et al. The prevalence of wrong level surgery among spine surgeons. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008; : 194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meinberg EG, Stern PJ. Incidence of wrong-site surgery among hand surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; : 193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsen FA III, Stephens L, Jette JL, Warme WJ, Posner KL. Lessons regarding the safety of orthopaedic patient care: an analysis of four hundred and sixty-four closed malpractice claims. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; : e201–e208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hariharan D, Lobo DN. Retained surgical sponges, needles and instruments. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013; : 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan IH, Jamil W, Lynn SM, Khan OH, Markland K, Giddins G. Analysis of NHSLA claims in orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics 2012; : e726–e731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toolan CC, Cartwright-Terry M, Scurr JR, Smout JD. Causes of successful medico-legal claims following amputation. Vascular 2014; : 346–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scurr VR, Scurr JRH, Scurr JH. Medico-legal claims following amputations in the UK and Ireland. Med Leg J 2012; : 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skevington SM, Langdon JE, Giddins G. ‘Skating on thin ice?’ Consultant surgeon’s contemporary experience of adverse surgical events. Psychol Health Med 2012; : 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]