Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to describe clinical characteristics and prevalence of carotid stenosis in patients with amaurosis fugax (AF).

Method

Patients diagnosed with AF and subjected to carotid ultrasound in 2004–2010 in Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg (n=302), were included, and data were retrospectively collected from medical records.

Results

The prevalence of significant carotid stenosis was 18.9%, and 14.2% of the subjects were subjected to carotid endarterectomy. Significant associations with risk of having ≥70% stenosis were male sex (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 2.62; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.26–5.46), current smoking (aOR: 6.26; 95% CI: 2.62–14.93), diabetes (aOR: 3.68; 95% CI: 1.37–9.90) and previous vasculitis (aOR: 10.78; 95% CI: 1.36–85.5). A majority of the patients (81.4%) was seen by an ophthalmologist prior to the first ultrasound. Only 1.7% of the patients exhibited retinal artery emboli at examination.

Conclusion

The prevalence of carotid stenosis among patients with AF is higher than has previously been demonstrated in stroke patients. An association with previously reported vascular risk factors and with vasculitis is seen in this patient group. Ocular findings are scarce.

Keywords: amaurosis fugax, carotid stenosis, carotid ultrasound, giant cell arteritis, transient ischemic attack, transient monocular visual loss

Introduction

Amaurosis fugax (AF) is defined as a transient monocular visual loss (TMVL) that lasts from seconds to minutes. Sometimes, but uncommonly, the episode may last for several hours.1 The symptom is caused by ischemia in the retina, the choroid or the optic nerve.2 The most common underlying mechanism is an embolus from the ipsilateral carotid artery.3 It is not uncommon for patients suffering from TMVL, presumably caused by retinal ischemia, to show signs of acute brain infarcts using neuroimaging.4 Patients with AF are therefore at risk of having a cerebral transient ischemic attack, retinal artery occlusion or stroke.2 AF is considered a form of transient ischemic attack.5

Carotid disease is one of the major causes of stroke in the world, and stroke itself is one of the most common causes of mortality and severe disability in adults.6 Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is another cause of AF, and it is hence important to analyze inflammatory parameters such as sedimentation rate (SR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) to minimize the risk of permanent visual loss.3

Ultrasound (US) of the carotid arteries is usually performed to detect possible stenoses of the carotids. If the patient has a significant carotid stenosis, he or she may be eligible for carotid endarterectomy, which is the most effective stroke prevention method in symptomatic patients.7

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of carotid stenosis in patients with AF. We also investigated possible/known risk factors for cardiovascular disease, symptoms during AF and findings at eye examination in order to determine possible predictors of carotid disease among AF patients.

Material and methods

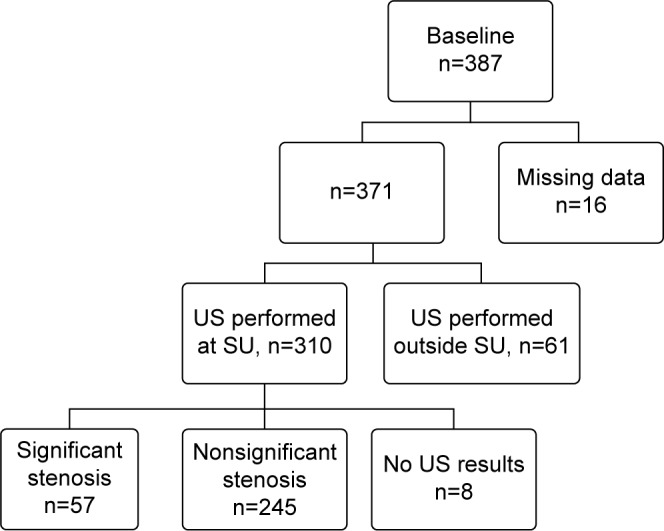

The study was approved by the ethical committee at the University of Gothenburg and the tenets of Helsinki were followed. According to the ethical committee, a consent from the patient is not necessary in this type of retrospective study. Study patients were identified through the Western region Initiative to Gather information on Atherosclerosis database.8 All patients in this study had undergone US between October 1, 2004 and December 31, 2010 at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg and were given the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code G45.3 (AF) as registered at The National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden within 6 months prior to the US. Patients were included in the study if they had received the ICD code G45.3, even if the duration of symptoms was atypical for AF. For 16 patients, medical journals could not be retrieved and 61 patients did their primary US at another hospital and later were referred to Sahlgrenska University Hospital for a carotid endarterectomy. These cases were excluded. This procedure resulted in 387 patients (Figure 1). A carotid stenosis of $70% was considered significant.

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion of patients subjected to carotid ultrasound due to amaurosis fugax.

Note: Identification/recruitment of study patients with inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Abbreviations: US, ultrasound; SU, Sahlgrenska University Hospital.

Data collected from medical records included age, sex, medical history of systemic and ocular disorders as well as present medications, smoking history, monocular or binocular symptoms, associated ocular or systemic symptoms during the AF episode(s) such as the extent of visual field defects, light phenomena, ocular pain, diplopia, vertigo, headache or palsy. Information was also gathered from findings during the eye examination (retinal emboli, edema of the optic disc or macula), whether the patient had been examined by an ophthalmologist, if the patient had been subjected to auscultation of the heart or carotid vessels, if an echocardiography had been performed and if inflammatory tests (SR, CRP) had been performed.

Statistics

For univariate statistical analysis, Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test or Fisher’s exact test were used as appropriate. For calculation of possible predictors for significant stenosis, binary logistic regression was used entering covariates in a backward stepwise manner. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS, version 22.0 for Mac (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used as the statistics software.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Of the 302 patients from whom US results could be retrieved, 57 (18.9%) had a carotid stenosis of ≥70%. The overall mean age was 65.9 years (standard deviation 13.5) with no significant difference between patients with or without carotid stenosis found using univariate analysis. The proportion of men was significantly higher in the group with significant carotid stenosis, 63.2%, as compared to 41.6% in the group with no significant stenosis. Additional single-parameter analyses revealed a higher proportion of current, as well as ever, smokers and patients with ischemic heart disease, hypertension and hyperlipidemia in the group with significant carotid stenosis. Previous vasculitis showed a borderline significant association with ≥70% stenosis. Previous or current eye diseases were not significantly associated with carotid disease. When applying logistic regression, only male sex, current smoking, diabetes and previous vasculitis were associated with significant carotid stenosis (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic data on patients with AF (n=302)

| No significant carotid stenosis* n=245 |

Significant carotid stenosis* n=57 |

P-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 65.1 (14.2) | 68.7 (10.5) | 0.065‡ |

| Median (range) | 68 (19–89) | 70 (47–88) | 0.223§ |

| Sex, n (%); n=302 | |||

| Female, n=164 | 143 (58.4) | 21 (36.8) | 0.005¶ |

| Male, n=138 | 102 (41.6) | 36 (63.2) | |

| Current smoker, n (%); n=241 | 32 (17) | 20 (37.7) s | 0.002¶ |

| Ever smoker,# n (%); n=154 | 86 (76.1) | 40 (97.6) | 0.002¶ |

| Systemic diseases, n (%) | |||

| Prior stroke, n=297 | 7 (2.9) | 3 (5.3) | 0.411¶ |

| Prior AF,‖ n=65 | 40 (78.4) | 13 (92.9) | 0.436¶ |

| Prior TIA, n=44 | 13 (41.9) | 6 (46.2) | 1.000¶ |

| Ischemic heart disease, n=294 | 32 (13.4) | 15 (26.8) | 0.024¶ |

| Hypertension, n=297 | 96 (39.8) | 36 (64.3) | 0.001¶ |

| Hyperlipidemia, n=294 | 87 (36.4) | 29 (52.7) | 0.032¶ |

| Diabetes, n=299 | 18 (7.4) | 13 (22.8) | 0.003¶ |

| Diet only, n=30 | 6 (35.3) | 4 (30.8) | 1.000¶ |

| Oral drugs,œ n=30 | 6 (35.3) | 8 (61.5) | 0.269¶ |

| Insulin,œ n=30 | 5 (29.4) | 1 (7.7) | 0.196¶ |

| Prior vasculitis,€ n=299 | 2 (0.8) | 3 (5.3) | 0.049¶ |

| Migraine, n=43 | 29 (78.4) | 5 (83.3) | 1.000¶ |

| Eye diseases, n (%); n=158 | 96 (73.3) | 19 (70.4) | 0.813¶ |

| Glaucoma, n=158 | 19 (14.5) | 2 (7.4) | 0.533¶ |

| Cataract,π n=158 | 53 (40.5) | 11 (40.7) | 1.000¶ |

| AMD, n=158 | 15 (11.5) | 4 (14.8) | 0.744¶ |

| Prior retinal vascular occlusions (artery/vein), n=158 | 3 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000¶ |

| AION or NA-AION, n=158 | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000¶ |

| Other eye diseases, n=158 | 41 (31.3) | 6 (22.2) | 0.488¶ |

Notes:

A stenosis of the carotid artery was denoted as significant if its value was ≥70%.

A P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Student’s t-test.

Mann–Whitney U test.

Fisher’s exact test.

Ever smoker includes current and previous smokers.

Prior AF was defined as an AF episode more than 2 months before the current episode.

Some patients had both oral drugs and insulin as diabetic treatment.

Wegener’s granulomatosis, polymyalgia rheumatica, temporal arteritis.

Including both patients with previous cataract surgery or diagnosed with cataract at the eye examination.

Abbreviations: AF, amaurosis fugax; AION, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy; AMD, age-related macular degeneration; NA-AION, non-arthritic ischemic optic neuropathy; SD, standard deviation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of possible predictors for significant stenosis in patients diagnosed with AF*

| Variable† | Regression coefficient | Standard error | aOR | 95% CI | P-value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.033 | 0.017 | 1.033 | 0.999–1.069 | 0.057 |

| Sex, male | 0.964 | 0.375 | 2.622 | 1.258–5.463 | 0.010 |

| Current smoker | 1.834 | 0.444 | 6.256 | 2.622–14.925 | <0.001 |

| Systemic diseases | |||||

| Prior stroke | 0.429 | 0.999 | 1.536 | 0.217–10.894 | 0.667 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0.522 | 0.457 | 1.685 | 0.688–4.129 | 0.254 |

| Hypertension | 0.542 | 0.391 | 1.719 | 0.799–3.700 | 0.166 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.373 | 0.370 | 1.453 | 0.703–3.000 | 0.313 |

| Diabetes§ | 1.303 | 0.505 | 3.680 | 1.368–9.896 | 0.010 |

| Prior vasculitis | 2.378 | 1.056 | 10.784 | 1.360–85.484 | 0.024 |

Notes:

Binary logistic regression using backwards stepwise entering of covariates.

N=233, including 51 patients with significant carotid stenosis and 182 patients with nonsignificant stenosis.

A P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Including both patients with oral drugs and/or insulin as diabetic treatment.

Abbreviations: AF, amaurosis fugax; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

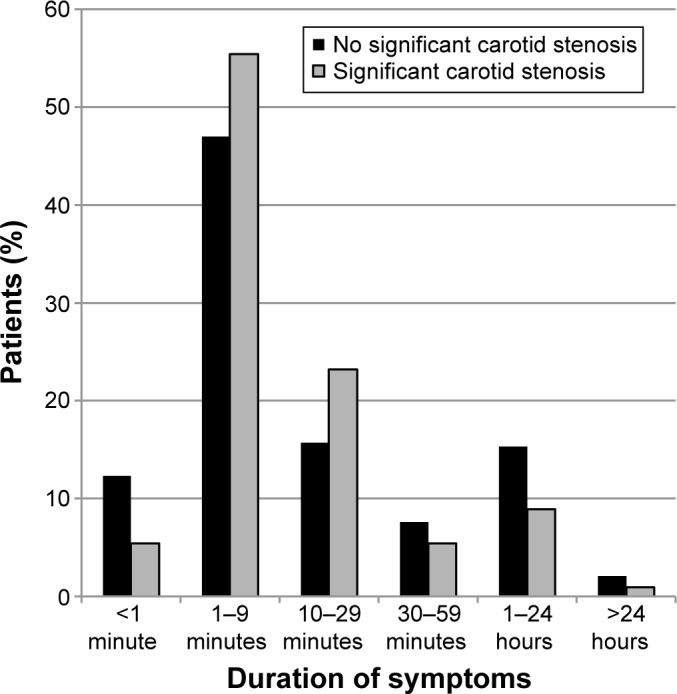

A vast majority of the patients (81.4%) were examined by an ophthalmologist prior to their primary carotid US. No statistically significant difference regarding symptoms or signs was seen between patients with and without carotid stenosis (Table 3). Most AF attacks (48.6%) lasted for 1–9 minutes, and 76.7% of all patients diagnosed as AF had episodes of visual loss that lasted for less than 30 minutes (Figure 2). No significant difference in duration of the AF episodes was seen between those patients diagnosed with carotid stenosis and those without. Three patients (1.6%) with nonsignificant carotid stenosis and one patient (2.6%) with significant stenosis exhibited retinal artery emboli at examination (P=0.525). For 69.0% of the patients, inflammatory parameters, SR and/or CRP, were measured prior to the US; in 96.6%, heart auscultation and/or pulse recording was performed. In 80.2% of the patients, the carotid arteries were auscultated; in 84.6% of the patients, an echocardiography was performed. No significant difference was seen in the proportion of patients having been subjected to these examinations when comparing those with and without carotid stenosis.

Table 3.

Symptoms during and in connection with AF attack and findings at the eye examination

| Signs and symptoms | No significant carotid stenosis* | Significant carotid stenosis* | P-value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monocular symptoms only,‡ n (%); n=274 (92.9) | |||

| Right eye, n (%) | 108 (49.8) | 31 (55.4) | 0.549 |

| Left eye, n (%) | 114 (52.5) | 26 (46.4) | 0.455 |

| Visual field impairment,§ n=232 | |||

| Entire visual field loss, n (%) | 144 (75.4) | 30 (73.2) | 0.843 |

| Partial visual field loss, n (%) | 45 (23.6) | 13 (31.7) | 0.320 |

| Light phenomena during or in connection with the AF episode, n (%) n=66 | 31 (58.5) | 5 (38.5) | 0.227 |

| Associated symptoms during or in connection with the AF episode | |||

| Headache, n (%); n=90 | 30 (40.0) | 4 (26.7) | 0.394 |

| Vertigo, n (%); n=80 | 20 (30.8) | 4 (26.7) | 1.000 |

| Pain or discomfort in the eye or round the eye, n (%); n=73 | 14 (23.3) | 2 (15.4) | 0.720 |

| Diplopia, n (%); n=74 | 7 (11.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.334 |

| Other, n (%); n=102 | 38 (45.2) | 7 (38.9) | 0.795 |

| Findings at the eye examination, n=231 | |||

| Macular edema, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Retinal artery embolus, n (%) | 3 (1.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0.525 |

Notes:

A stenosis of the carotid artery was denoted as significant if its value was ≥70%.

A P-value <0.05 was considered significant. Fisher’s exact test was used.

Some patients hade monocular symptoms from both the right and left eye alternately.

Some patients hade both entire and partial visual field loss and are therefore included in both the groups. Some patients’ had homonym visual field loss. They were included but were neither categorized as entire or partial visual loss.

Abbreviation: AF, amaurosis fugax.

Figure 2.

Duration of symptoms during an episode of AF.

Notes: Proportion of patients with different estimated lengths of AF attacks. Both patients with and without carotid stenosis are shown.

Abbreviation: AF, amaurosis fugax.

Discussion

The prevalence of significant carotid stenosis reported in this study was 18.9%. Little is known on the prevalence of carotid stenosis in patients with AF. However, compared to studies investigating the prevalence of carotid stenosis in patients with ischemic cerebral stroke, in which numbers of 5%–12% have been reported,9,10 this is a fairly high number. The most common etiology behind AF is an embolus from the ipsilateral carotid artery, ie, a vascular disorder.11 It is thus not surprising that the present study found an association between carotid stenosis and male sex, smoking and diabetes, which are known risk factors for cardiovascular disease.12 In addition, of the five patients with a history of vasculitis, three had a significant carotid stenosis. Large cell vasculitis, including GCA, is a chronic inflammatory disease that results in luminal stenosis and/or vessel occlusion in the aorta and its primary branches.13 It is hence not surprising to find carotid stenosis in patients with vasculitis, and the relative contribution of atherosclerosis and arteritis in these patients may be difficult to distinguish. Since GCA is a disease that may lead to permanent visual loss, it is recommended to determine inflammatory parameters (SR and/or CRP) in all patients seeking care for AF symptoms.3 In the present study, a blood test for SR and/or CRP was done only in 69.0% of the cases. The low number may be due to underreporting, a negative consequence of the retrospective design of the study.

The duration of the AF episode did not differ between patients with and without carotid stenosis. Median time of the AF symptoms was between 1 and 9 minutes in both the groups, which is similar to what has previously been reported by Biousse and Trobe.2 It is known that visual loss can be either complete or partial, as seen in the present study. It has also been described that if the choroidal circulation is affected, the visual field loss may be patchy.14 In this study, six of the patients had persistent partial or complete visual field loss still after 24 hours. Of these patients, one was shown to have a cerebral aneurysm. One had hemianopsia due to a stroke and two were later diagnosed as having central retinal artery occlusion. The symptoms of one patient were eventually considered to be caused by vitreous detachment and for one patient no explanation was found to the persistent visual loss. We included these patients in the study despite the permanent/long duration of the visual loss since they were initially registered as AF with the ICD-10 code G45.3.

A majority of the patients (81.4%) were examined by an ophthalmologist prior to the US. Most ophthalmologists are thus regularly exposed to this category of patients. It has been shown that the number of patients who consult an ophthalmologist because of symptoms related to carotid artery stenosis has increased in recent years.15 However, findings during an eye examination are usually rare, providing poor guidance in diagnostic decision-making. In the present study, only 1.7% of the patients exhibited visible retinal artery emboli at examination and there was no significant difference between patients with or without carotid stenosis. This low number may suggest that the patients need not see an ophthalmologist as the primary consultant. A limitation of the study, which is related to the retrospective design, is the lack of information on the number of patients contacting a doctor for TMVL who were not diagnosed as AF. It is probable that ophthalmologists are better than other specialists at finding alternative causes of transient visual disturbances such as migraine and vitreous detachment. Consulting an ophthalmologist as the first medical contact could thus avoid unnecessary further examinations and/or admission to hospital.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study shows a high prevalence of carotid stenosis in patients diagnosed with AF. An association with known vascular risk factors is confirmed as well as with previous/current vasculitis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (#2011-3132), Swedish government (“Agreement concerning research and education of doctors”; ALF-GBG-145921), Göteborg Medical Society, Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation, Dr Reinhard Marcuses Foundation, Konung Gustaf V:s och Drottning Victorias Frimurarestiftelse, Hjalmar Svensson Foundation, Greta Andersson Foundation, Herman Svensson Foundation, Ögonfonden, De Blindas Vänner, and Kronprinsessan Margaretas Arbetsnämnd för Synskadade. The abstract of this paper was presented at the Nordic Congress of Ophthalmology, Stockholm, Sweden, on August 20–23, 2014. The conference abstract was published in the Acta Ophthalmologica Special Issue: Abstracts of the Nordic Congress of Ophthalmology, 2014;92(supplement s254):1–23.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Current management of amaurosis fugax. The Amaurosis Fugax Study Group. Stroke. 1990;21(2):201–208. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biousse V, Trobe JD. Transient monocular visual loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(4):717–721. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayreh SS. Acute retinal arterial occlusive disorders. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30(5):359–394. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helenius J, Arsava EM, Goldstein JN, et al. Concurrent acute brain infarcts in patients with monocular visual loss. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(2):286–293. doi: 10.1002/ana.23597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKibbin M, Verma D. Recurrent amaurosis fugax without haemodynamically significant ipsilateral carotid stenosis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77(2):224–226. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halliday AW, Lees T, Kamugasha D, et al. Waiting times for carotid endarterectomy in UK: observational study. BMJ. 2009;338:b1847. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulkarni SR, Gohel MS, Bulbulia RA, Whyman MR, Poskitt KR. The importance of early carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91(3):210–213. doi: 10.1308/003588409X359312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strömberg S, Nordanstig A, Bentzel T, Österberg K, Bergström GM. Risk of early recurrent stroke in symptomatic carotid stenosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49(2):137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flaherty ML, Kissela B, Khoury JC, et al. Carotid artery stenosis as a cause of stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;40(1):36–41. doi: 10.1159/000341410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Litsky J, Stilp E, Njoh R, Mena-Hurtado C. Management of symptomatic carotid disease in 2014. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16(3):462. doi: 10.1007/s11886-013-0462-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hankey GJ, Slattery JM, Warlow CP. Transient ischaemic attacks: which patients are at high (and low) risk of serious vascular events? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(8):640–652. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.8.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Larson MG, Massaro JM, Vasan RS. Predicting the 30-year risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2009;119(24):3078–3084. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grayson PC, Tomasson G, Cuthbertson D, et al. Association of vascular physical examination findings and arteriographic lesions in large vessel vasculitis. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(2):303–309. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petzold A, Islam N, Plant GT. Patterns of non-embolic transient monocular visual field loss. J Neurol. 2013;260(7):1889–1900. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6902-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo RJ, Liu SR, Li XM, Zhuo YH, Tian Z. Fifty-eight cases of ocular ischemic diseases caused by carotid artery stenosis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123(19):2662–2665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]