Abstract

The regulatory roles of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in transcriptional coactivators are still largely unknown. Here, we have shown that the peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ (PPARγ) coactivator α (PGC-1α, encoded by Ppargc1a) is functionally regulated by the lncRNA taurine-upregulated gene 1 (Tug1). Further, we have described a role for Tug1 in the regulation of mitochondrial function in podocytes. Using a murine model of diabetic nephropathy (DN), we performed an unbiased RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of kidney glomeruli and identified Tug1 as a differentially expressed lncRNA in the diabetic milieu. Podocyte-specific overexpression (OE) of Tug1 in diabetic mice improved the biochemical and histological features associated with DN. Unexpectedly, we found that Tug1 OE rescued the expression of PGC-1α and its transcriptional targets. Tug1 OE was also associated with improvements in mitochondrial bioenergetics in the podocytes of diabetic mice. Mechanistically, we found that the interaction between Tug1 and PGC-1α promotes the binding of PGC-1α to its own promoter. We identified a Tug1-binding element (TBE) upstream of the Ppargc1a gene and showed that Tug1 binds with the TBE to enhance Ppargc1a promoter activity. These findings indicate that a direct interaction between PGC-1α and Tug1 modulates mitochondrial bioenergetics in podocytes in the diabetic milieu.

Introduction

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a heterogeneous class of long (>200 nucleotides) transcripts with an apparent lack of protein-coding potential (1). It is evident that lncRNAs have a wide range of biological functions, and their aberrant expression has been associated with diverse pathologies including cancer as well as cardiac, neurological, and metabolic diseases (2–4). Mechanisms underlying the broad functions of lncRNAs are rapidly emerging. Several lncRNAs control gene expression by recruiting regulating complexes to genomic sites located near (in cis) or far (in trans), whereas some others appear to function as scaffolds or act as decoys for proteins or miRs (5, 6). Despite all these advances, the molecular functions of lncRNAs in many human diseases remain elusive, and more detailed functional studies are needed to unravel the biological roles of lncRNAs.

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a microvascular complication of diabetes and the leading cause of end-stage renal disease in the United States (7). Among many factors implicated in the pathogenesis of DN, the PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α, encoded by Ppargc1a in mice), whose expression is typically reduced in diabetes, has gained attention as a key mediator of mitochondrial dysfunction and progression of DN (8–12). The central role of PGC-1α in mitochondrial bioenergetics and respiration is well known (13, 14). This has been elegantly demonstrated in several gain- and loss-of-function studies. Mice lacking PGC-1α display a significant reduction in the expression of genes associated with oxidative phosphorylation and reduced mitochondrial content (15–18). In contrast, transgenic overexpression (OE) of Ppargc1a leads to a significant increase in mitochondrial content and increased expression of mitochondrial genes (19–21).

PGC-1α regulates, and is regulated by, a number of well-known factors related to cellular energy and mitochondrial homeostasis (13). PGC-1α acts in an autoregulatory loop to enhance its own transcriptional output (13, 22, 23). The tight and multilayered regulation of PGC-1α is not surprising, given its critical role in linking many physiological stimuli to specific metabolic programs associated with enhanced mitochondrial bioenergetics. New mechanisms underlying the tight regulation of PGC-1α continue to emerge (24). However, despite these advances, the role of lncRNAs in the regulation of PGC-1α remains largely unknown.

Here, we unexpectedly found that taurine upregulated gene 1 (Tug1), an evolutionarily conserved long intergenic noncoding RNA, is a regulator of PGC-1α transcription and mitochondrial bioenergetics in DN. We found that Tug1 expression was significantly repressed in the podocytes of diabetic mice and demonstrate that podocyte-specific OE of Tug1 in diabetic mice can rescue PGC-1α expression, leading to improved mitochondrial bioenergetics, along with improvements in several key features of DN. We provide mechanistic evidence for a direct interaction between Tug1 and PGC-1α protein. We also provide evidence indicating that the interaction between Tug1 and PGC-1α promotes the binding of PGC-1α to its own promoter. We have also identified a Tug1-binding site upstream of the Ppargc1a promoter region. The Tug1 interaction with this binding site, our data suggest, helps to trigger increased transcription of Ppargc1a mRNA.

The discovery that a lncRNA can regulate PGC-1α adds an unexpected layer of complexity to PGC-1α regulation and expands on the spectrum of transcriptional regulation of this key regulator of energy metabolism.

Results

Evidence linking Tug1 to DN progression in vivo.

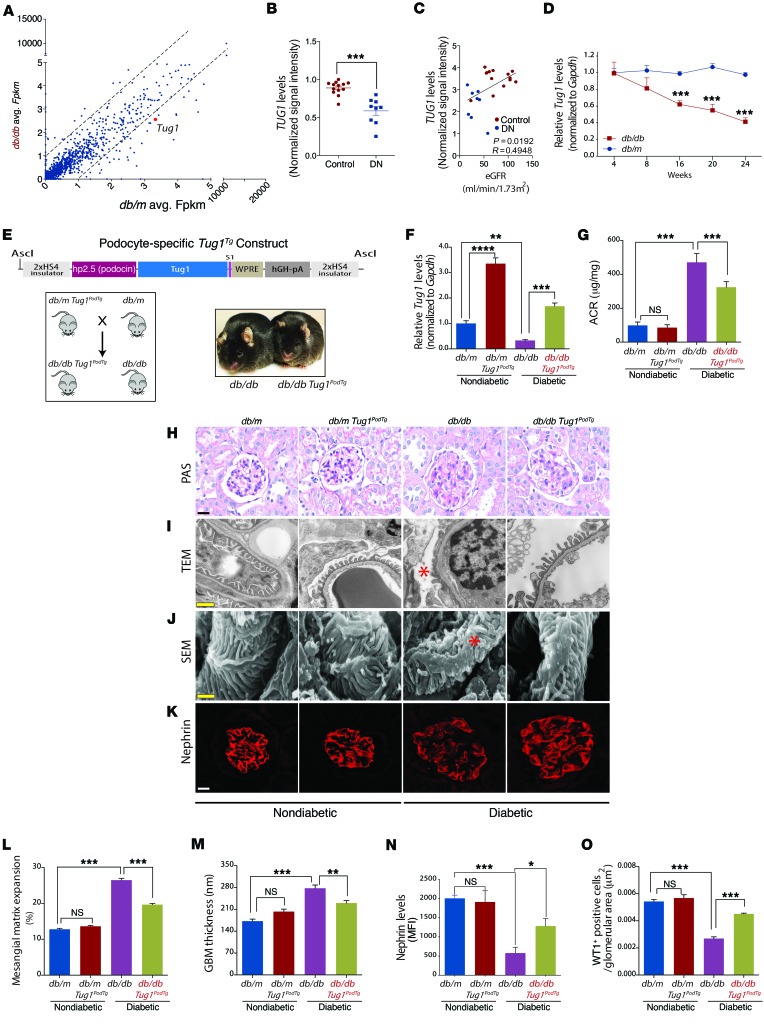

To identify which lncRNAs are differentially expressed in DN, we performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of isolated kidney glomeruli from type 2 diabetic (db/db) mice compared with glomeruli from nondiabetic (db/m) control mice. Our analysis of transcripts classified as noncoding RNAs revealed several differentially regulated noncoding RNAs (Figure 1A). lncRNAs were selected for further analysis on the basis of whether they exhibited robust evolutionary conservation and whether their expression levels in mice were relevant in human subjects with DN. Given these restricted criteria, we selected Tug1, which was reduced in our RNA-seq analysis, exhibited robust conservation between several vertebrate species, including humans (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B; supplemental material available online with this article; doi:10.1172/JCI87927DS1), and was significantly reduced in microdissected glomeruli from subjects with DN based on a publicly available data set from Nephroseq (Figure 1B) (25). From the same database, lower expression levels of TUG1 correlated with reduced levels of estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFRs) in patients with DN (Figure 1C). We next confirmed previous observations indicating that Tug1 was broadly and abundantly expressed in different tissues and localizes to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Supplemental Figure 1, C and D) (26, 27). RNA ISH revealed Tug1 to be predominantly nuclear, with some cytoplasmic staining within glomeruli and tubules (Supplemental Figure 1E). To confirm the results of our initial screen, we assessed the temporal profile of Tug1 expression over several time points and found Tug1 levels to be significantly decreased over time in podocytes from diabetic mice compared with levels in controls (Figure 1D and Supplemental Figure 1F). These results were verified in mouse podocytes cultured under high glucose (HG, 25 mM) versus normal glucose (NG, 5 mM) conditions (Supplemental Figure 1G).

Figure 1. Tug1 OE in podocytes protects against features of DN.

(A) Scatter plot of RNA-seq values for individual transcripts classified as noncoding RNAs. (B) Nephroseq expression data for TUG1 in control subjects (n = 13) and in subjects with DN (n =9). (C) Linear regression analysis of the same subjects in B, with eGFR values. (D) In vivo time course analysis of Tug1 expression in podocytes from diabetic and nondiabetic mice (n = 6 mice/group). (E) Schematic of Tug1Tg construct. Tug1 cDNA was cloned upstream of WPRE and hGH polyadenylation sequences. Expression is driven by the human NPHS2 (podocin) promoter. These elements are flanked by HS4 insulator sequences. Illustration shows the mating strategy to generate podocyte-specific diabetic Tug1PodTg mice. Representative image of adult control diabetic (db/db) and diabetic Tug1PodTg mice. (F) qPCR analysis of RNA isolated from podocytes measuring Tug1 levels in 24-week-old db/m (n = 5), db/db (n =5), db/m Tug1PodTg (n = 7), and db/db Tug1PodTg (n = 7) mice. (G) ACR analysis demonstrating a significant reduction in albuminuria in 24-week-old diabetic Tug1PodTg mice compared with that in controls, as in F. (H–K) Representative (H) PAS-stained image; (I) TEM micrographs; (J) SEM micrographs; and (K) nephrin immunofluorescence confocal micrographs. Red asterisks on the TEM and SEM micrographs denote effaced podocyte foot processes. Scale bars: 50 μM (H and K), 0.5 μM (I), and 1 μM (J). (L) Quantification of mesangial matrix expansion determined as the percentage of PAS-positive area/glomerular area. (M) Quantification of GBM thickness. (N) Quantification of nephrin mean fluorescence intensity (MFI)/glomerular area. (O) Quantification of WT1-positive cells/glomerular area. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001, by 2-tailed Student’s t test (B), linear regression analysis (C), and 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc analysis (L–O). Data represent the mean ± SEM.

To assess the contribution of Tug1 to DN progression in vivo, we generated podocyte-specific Tug1-transgenic mice under the control of the human podocyte–specific podocin (NPHS2) promoter (Figure 1E, schematic). There are 3 isoforms for murine Tug1 (Tug1-a, -b, -c). We used the longest isoform, Tug1-c, which contains all overlapping exon sequences, to generate Tug1PodTg mice. Two Tug1PodTg founder mice were generated. While we found no difference in nonpodoctye Tug1 levels between transgenic and WT mice, quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis revealed that Tug1 RNA levels were significantly higher in transgenic podocytes compared with levels in WT control podocytes (Supplemental Figure 2A). To investigate whether targeted OE of Tug1 in podocytes rescues key features of the DN phenotype, we crossed Tug1 mice with Leprdb/+ mice to generate diabetic Leprdb/db Tug1 mice (hereafter referred to as db/db Tug1PodTg mice) (Figure 1E). db/db Tug1PodTg mice exhibited similar BW, blood glucose, and kidney/BW ratios compared with db/db controls (Supplemental Figure 2, B–D). qPCR analysis of podocytes from nondiabetic and diabetic TugPodTg mice revealed a robust increase in Tug1 expression compared with that observed in controls (Figure 1F). Importantly, podocyte-specific Tug1 OE led to a significant reduction in albuminuria as measured by the albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) (Figure 1G) and reduced mesangial matrix expansion (Figure 1, H and L). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs revealed improvements in podocyte foot process effacement and reduced glomerular basement membrane (GBM) thickening (Figure 1, I–J, and M). Additionally, we observed a rescue of nephrin expression by immunofluorescence analysis and a significant increase in the number of podocytes in diabetic db/db TugPodTg mice compared with controls (Figure 1, K, N, and O and Supplemental Figure 2E). These findings provide strong evidence indicating that Tug1 plays a key role in the progression of DN.

Tug1 is a regulator of the PGC-1α pathway.

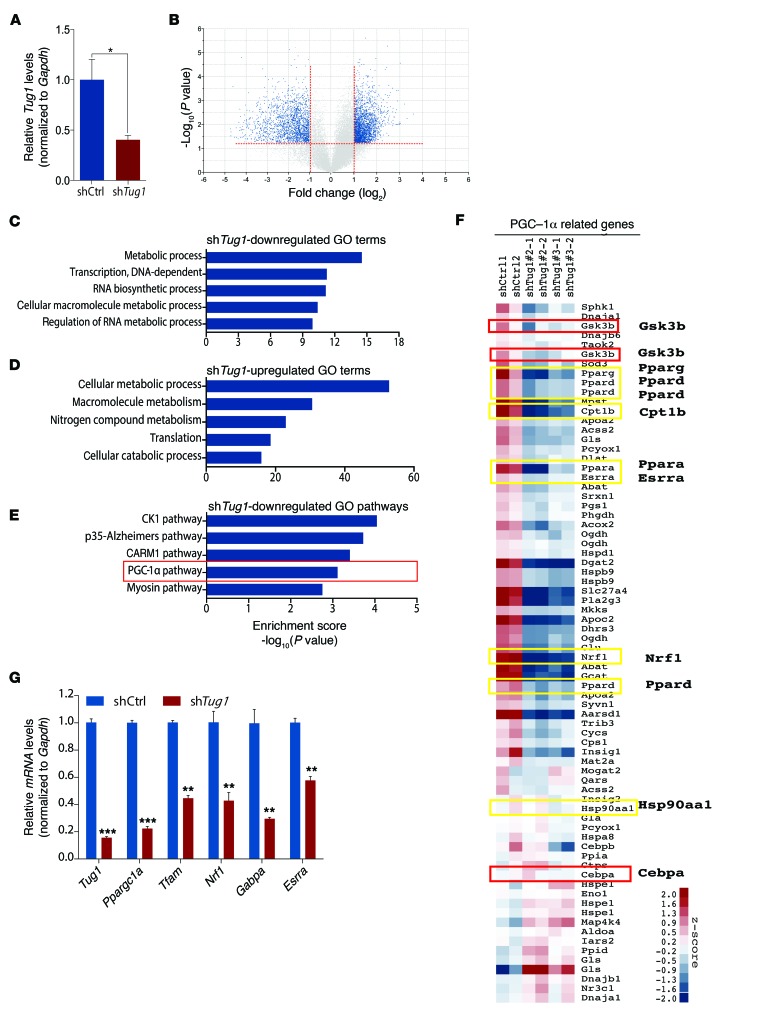

To unravel the mechanism by which Tug1 exerted its modulatory effect on DN, we sought to determine the genome-wide transcriptomic consequences of Tug1 depletion in podocytes. We performed microarray analysis on podocytes stably transfected with pGIPZ shTug1 lentiviral constructs (Figure 2A). This approach revealed approximately 400 genes that were positively regulated and approximately 560 genes that were negatively regulated by Tug1 (Figure 2B). Gene ontology (GO) analysis for biological processes affected by Tug1 suggested its involvement in several metabolic and biosynthetic pathways (Figure 2, C and D). Importantly, genes involved in PGC-1α pathways comprised a subset of genes whose levels were significantly reduced following Tug1 knockdown (KD) (Figure 2, E and F). Since PGC-1α is a well-known master regulator of mitochondrial function, whose expression is significantly reduced in diabetes (28, 29), we next focused our efforts on establishing a potential link between Tug1 and PGC-1α. We first tested whether Ppargc1a RNA levels were affected by Tug1 and found that Ppargc1a and several of its transcriptional targets (Tfam, Nrf1, Gabpa, and Esrra) were significantly reduced in Tug1-KD podocytes compared with controls (Figure 2G).

Figure 2. Tug1 mediates expression of PGC-1α pathway genes.

(A) Gene expression analysis of RNA from pGIPZ-shControl (shCtrl) or shTug1 lentivirus–transduced podocytes used for microarray analysis. (B) Volcano plot of microarray data generated from Tug1-KD podocytes compared with controls. A cutoff of a log2 fold-change greater than 2 and a –log10 (P value) greater than 1 was used for downstream pathway analysis. (C–E) Bioinformatics analysis of differentially regulated Tug1 target genes. (C and D) Biological processes GO terms from genes differentially up- and downregulated by Tug1. (E) Pathway analysis of Tug1-downregulated genes. (F) Hierarchical clustering analysis of RNA expression levels of PGC-1α–related genes in control podocytes compared with podocytes harboring stable KD of Tug1. Yellow boxes highlight genes that are direct targets of PGC-1α, and red boxes highlight its upstream regulators. (G) qPCR validation of several direct targets of PGC-1α. Expression values were normalized to Gapdh internal controls. Cell culture experiments were repeated at least 3 times. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by 2-tailed Student’s t test (A and G). See Supplemental Methods for the data analysis steps related to B–F. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Tug1 regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics.

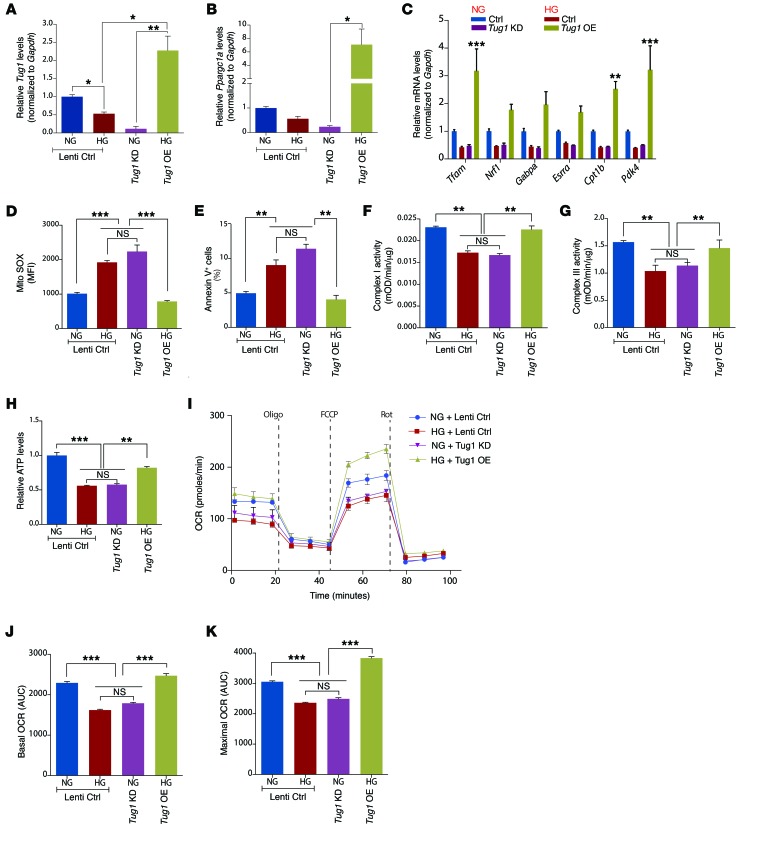

This unexpected link between Tug1 and PGC-1α prompted us to investigate whether Tug1 also influences mitochondrial bioenergetics, a key feature of PGC-1α. To evaluate the effect of Tug1 on mitochondrial oxygen consumption, mitochondrial ROS, and mitochondrial complex activity, we generated 2 stable podocyte cell lines for OE and KD of Tug1 using modified versions of the CRISPR/Cas9 system with guide RNA pairs targeted to the promoter region and exon 3 of Tug1 (Supplemental Figure 3). We initially validated our findings in cultured podocytes and observed that Tug1 and Ppargc1a RNA levels were suppressed in podocytes cultured under HG conditions (25 mM) (Figure 3, A and B). Importantly, Tug1-KD cells cultured in NG conditions also exhibited reduced Ppargc1a expression, mimicking HG conditions. However, Tug1 OE prevented an HG-mediated reduction in Ppargc1a mRNA and caused OE of Ppargc1a mRNA compared with controls (Figure 3, A and B). Since it was important to assess the effect of Tug1 on downstream targets of PGC-1α, the relative expression levels for mRNA targets of PGC-1α were analyzed in cultured podocytes. We observed that Tug1 OE or KD modulated multiple downstream targets of PGC-1α, including Tfam, Nrf1, Gabpa (also known as Nrf2), Esrra, Cpt1b, and Pdk4 (Figure 3C). To test whether this pattern of regulation is conserved in different tissues, we depleted Tug1 levels in C2C12 (a myoblast cell line) and AML12 (a hepatocyte cell line) cells. Following Tug1 KD in both cell lines, we observed a significant reduction in Ppargc1a mRNA levels, similar to our observations in podocytes (Supplemental Figure 4). Furthermore, Tug1 KD in these cell lines led to similar reductions in several transcriptional targets of PGC-1α (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 3. Tug1 modulates Ppargc1a mRNA and mitochondrial bioenergetics in vitro.

(A and B) qPCR analysis of Ppargc1a and Tug1 in control (Lenti ctrl), Tug1-KD, or Tug1-OE cultured podocytes under NG or HG conditions. (C) qPCR of selected PGC-1α direct targets in podocytes from A. (D) Measurement of mitochondrial ROS in cultured podocytes, measured by flow cytometry as the MFI of MitoSOX. (E) Flow cytometric determination of the percentage of podocytes that underwent apoptosis as measured by annexin V–FITC+ cells. (F and G) Measurement of complex I and III activity in mitochondria isolated from cultured podocytes. (H) Relative ATP levels in podocytes, normalized to total protein content. (I–K) Mitochondrial OCR analysis of cultured podocytes using the Seahorse XF24 Bioanalyzer device. Oligomycin (2 μM), FCCP (2 μM), and rotenone (0.5 μM)/antimycin A (0.5 μM) were added at the times indicated by dashed lines. Basal and maximal respiratory rates of podocytes were determined by calculating the AUC. Cell culture experiments were repeated at least 3 times. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc analysis. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. mOD, milli optical density.

Next, we examined the effect of Tug1 on HG-induced ROS and apoptosis in Tug1-mutant podocytes. We found that Tug1 KD in NG conditions led to increased mitochondrial ROS and apoptosis, similar to the effect observed in HG conditions. Tug1 OE, however, prevented HG-induced increases in mitochondrial ROS and apoptosis (Figure 3, D and E). We also observed that Tug1 KD led to repressed complex I and III activity, whereas Tug1 OE in HG conditions restored complex activity to NG levels (Figure 3, F and G). We found that changes in complex I and III activity were not due to changes in protein expression levels of these complexes (Supplemental Figure 5A). No changes were observed in complex II or IV activity (Supplemental Figure 5, B and C). Importantly, Tug1 KD led to reduced ATP levels, similar to what was observed in HG conditions, whereas Tug1 OE rescued the HG effect on ATP levels (Figure 3, H). Finally, Tug1 KD led to a reduction in both basal and maximal oxygen consumption rates (OCRs), whereas Tug1 OE in HG conditions dramatically increased basal and maximal OCRs (Figure 3, I–K). To test whether Tug1-mediated changes in mitochondrial function are linked to PGC-1α, we knocked down PGC-1α in cultured podocytes and found that PGC-1α KD led to significant reductions in complex I and III activity in NG conditions, mimicking HG and Tug1-KD conditions (Supplemental Figure 5, D, E, and G). Consistent with these findings, transient OE of PGC-1α in Tug1-KD podocytes rescued Tug1-mediated reductions in basal OCR levels (Supplemental Figure 5, F and H).

Finally, to test whether PGC-1α is necessary to mediate the effect of Tug1 on HG-induced podocyte injury, we performed siRNA loss-of-function experiments targeting PGC-1α levels in Tug1-OE cells cultured in HG conditions. We found that PGC-1α KD partially abolished the Tug1-mediated protection against HG-induced podocyte injury (Supplemental Figure 6A). Conversely, OE of PGC-1α alone in podocytes prevented HG-induced apoptosis compared with controls (Supplemental Figure 6B). Taken together, these data suggest that the Tug1/PGC-1α axis is important for the prevention of HG-induced apoptosis in podocytes.

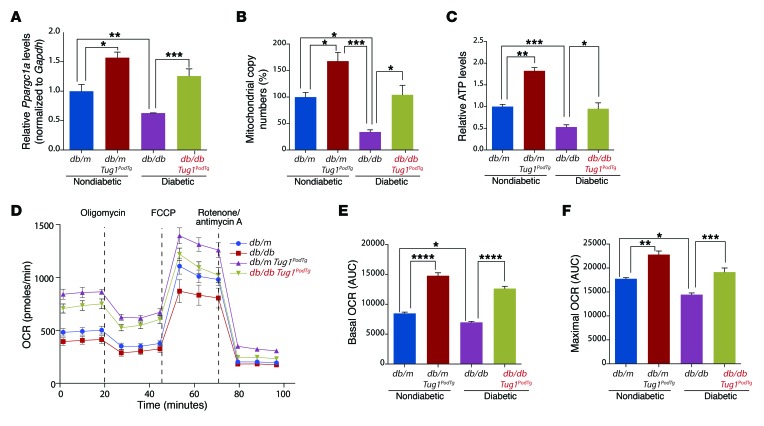

To confirm these observations in vivo, we analyzed isolated podocytes from db/db Tug1PodTg and db/db control mice. In line with our in vitro results, qPCR analysis revealed an increase in Ppargc1a mRNA levels in both nondiabetic and diabetic Tug1PodTg mice compared with levels in controls (Figure 4A). RNA levels of the well-known PGC-1α targets Nrf1, Gabpa, and Esrra were similarly elevated in nondiabetic and diabetic Tug1PodTg mice compared with levels detected in controls (Supplemental Figure 7, A–C). Tug1 OE in nondiabetic and diabetic mice led to increases in total mitochondrial content and elevated ATP levels compared with controls (Figure 4, B and C). Podocytes from nondiabetic and diabetic Tug1PodTg exhibited an increase in basal and maximal OCRs compared with that detected in controls (Figure 4, D–F). Finally, mitochondria were more elongated and the mitochondrial aspect ratio, a measure of mitochondrial fragmentation, was significantly improved in db/db Tug1PodTg mice compared with controls (Supplemental Figure 8, A and B). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Tug1 expression plays an important role in mitochondrial bioenergetics via its regulatory effect on PGC-1α expression.

Figure 4. Tug1 modulates Ppargc1a mRNA and mitochondrial bioenergetics in vivo.

(A) qPCR analysis of Ppargc1a RNA levels and (B) determination of mitochondrial copy numbers in isolated podocytes from db/m (n = 5), db/db (n = 5), db/m Tug1PodTg (n = 4), and db/db Tug1PodTg (n = 7) mice. (C) Relative ATP levels in freshly isolated podocytes from the groups in A (n = 4 mice/group). (D–F) Mitochondrial OCR analysis using the Seahorse XF24 Bioanalyzer device in cultured podocytes isolated from the groups in A. Oligomycin (2 μM), FCCP (2 μM), and rotenone (0.5 μM)/antimycin A (0.5 μM) were added at the times indicated by dashed lines. Basal and maximal respiratory rates of podocytes were determined by calculating the AUC for the groups from A. (E) Basal and (F) maximal mitochondrial OCR rates compared with controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc analysis. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Tug1 binds to an upstream PGC-1α enhancer element.

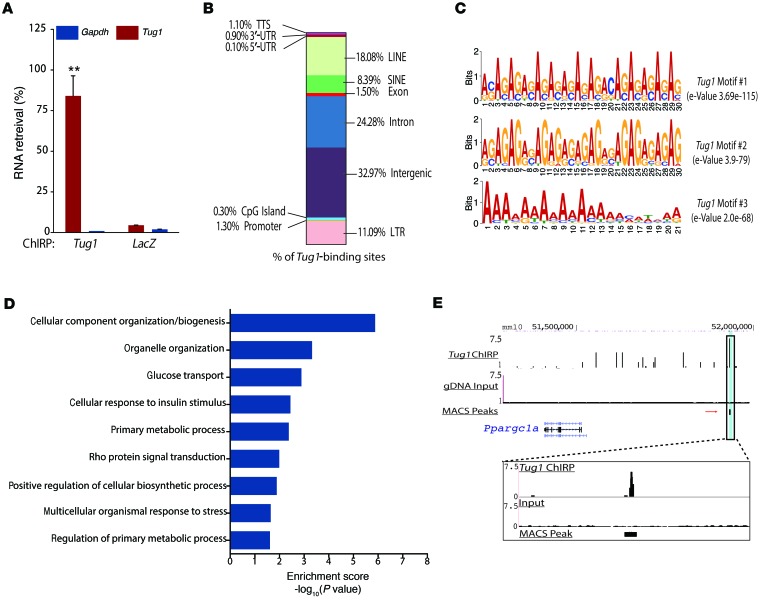

We were interested in determining how Tug1 interacts with PGC-1α. We used the genome-wide chromatin isolation by RNA purification–sequencing (ChIRP-seq) assay to map Tug1-binding sites genome wide in mouse podocytes (30). We designed 44 biotinylated Tug1 oligonucleotides spanning the entire length of Tug1 exons and prepared chromatin from cultured mouse podocytes. We confirmed a significant recovery of Tug1 RNA in Tug1-pulldown samples and did not observe recovery of LacZ RNA or nonspecific Gapdh mRNA (Figure 5A). Peak calling by model-based analysis for ChIP-seq (MACS) revealed approximately 3,000 putative Tug1-binding sites genome wide (31). Localization of Tug1-binding sites revealed enrichment in intergenic and repetitive regions with an average size of 300 to 500 bp in length (Figure 5B). DNA motif analysis of Tug1-binding sites revealed 3 significantly enriched motifs with similar characteristics: the top 2 motifs consisted of AG-purine stretches (e-value: 3.69e-115, e-value: 3.9e-79), and the third consisted of a stretch of adenines (Figure 5C). GO analysis of genes proximal and distal to Tug1-binding sites demonstrated enrichment in processes related to cellular metabolism, biosynthetic processes, glucose transport, and response to insulin signaling (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. ChIRP-seq analysis reveals genome-wide binding sites for Tug1, including a TBE upstream of the Ppargc1a promoter.

(A) Biotinylated Tug1 antisense DNA probes retrieved approximately 77% of total Tug1 RNA. Biotinylated LacZ antisense DNA probes were unable to retrieve either RNA. **P < 0.01, by 2-tailed Student’s t test. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (B) Percentage of Tug1-binding sites localized to different regions within the genome. LTR, long-terminal repeat; LINE, long-interspersed repetitive element; SINE, short-interspersed repetitive element. (C) Purine-rich stretches, either GA repeats or A repeats, represented the top scoring motifs among Tug1-binding sites. (D) Top GO analysis categories of biological processes related to Tug1-binding sites represented as enrichment scores: –log10(P value). (E) ChIRP-seq tag density at an intergenic, putative TBE approximately 400 kb upstream of the Ppargc1a gene promoter. Data are represented as Tug1-pulldown compared with input controls. Track heights were normalized to allow for comparison between groups. Tug1-pulldown data were generated from overlapping peak data from biological replicates of Tug1-odd pulldown and Tug1-even pulldown samples compared with input. Zoom inset highlights the peak height, and the location of MACS verified the peak. Aligned reads were used for peak calling of the ChIRP regions using MACS, version 1.4.0. gDNA, genomic DNA. Statistically significant ChIRP-enriched regions (peaks) were identified by comparison with input, using a P-value threshold of 10–5. Cell culture experiments were repeated at least 3 times. GO analysis was applied to peaks to determine the roles played in certain biological pathways or GO terms.

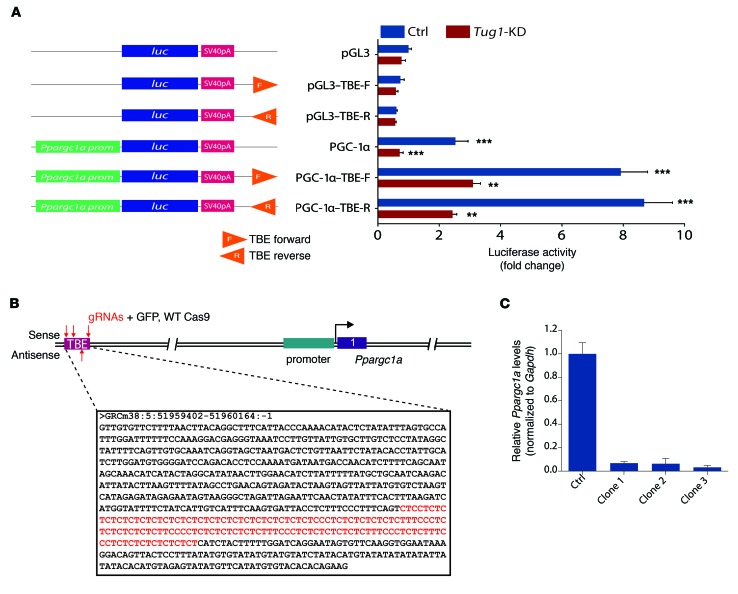

We next focused on a MACS peak approximately 400 kb upstream of the Ppargc1a transcription start site (TSS) (Figure 5E). Subsequent sequence analysis revealed that this stretch of DNA consisted of the predicted AG repeats. We classified this segment as a putative Tug1-binding element (TBE) and cloned this element into a Ppargc1a gene promoter–luciferase reporter construct to test whether this element could enhance Ppargc1a promoter activity. We cloned the elements in forward or reverse directions downstream of the promoter-luciferase cassette to mimic the potential enhancer activity (Figure 6A, left panel). The TBE elements alone did not elicit any changes in luciferase activity. However, when these elements were included on constructs harboring the Ppargc1a promoter (2 kb upstream of the TSS), we observed a robust induction of luciferase reporter activity compared with the reporter activity observed with the Ppargc1a promoter alone. To confirm that Tug1 is necessary for the increased promoter activity, we used Tug1-KD podocytes and observed greatly reduced luciferase reporter activity in Tug1-KD cells (Figure 6A, right panel). Finally, to verify the veracity of the TBE to mediate the effect of Tug1 on Ppargc1a RNA, we targeted the TBE sequence in podocyte genomic DNA using CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing techniques (Figure 6B). We generated 29 clones, 3 of which demonstrated dramatic reductions in Ppargc1a mRNA levels (Figure 6C). Together, these data illustrate that a TBE approximately 400 kb upstream of the Ppargc1a promoter can regulate PGC-1α expression.

Figure 6. Tug1 enhances Ppargc1a promoter activity via the TBE.

(A) Schematic of Ppargc1a promoter-luciferase constructs. Right, luciferase reporter activity in control and Tug1-KD podocytes. Inclusion of the TBE leads to robust enhancement of promoter activity, which is significantly attenuated in Tug1-KD cells. **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, by 2-tailed Student’s t test. luc, luciferase; F, forward; R, reverse. (B) Schematic of the genomic context of the TBE. The highlighted sequences refer to the sense strand of the TBE. The GA-repeat motif is located in the antisense strand. Genomic coordinates refer to Ensembl mouse genome assembly GRCm38. Red arrows indicate the position of the sgRNAs designed to target the TBE element. gRNAs, guide RNAs. (C) qPCR analysis of Ppargc1a mRNA in control podocytes and 3 independent TBE targeted clones. Expression values normalized to Gapdh internal controls. Cell culture experiments repeated at least 3 times. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Ctrl, control.

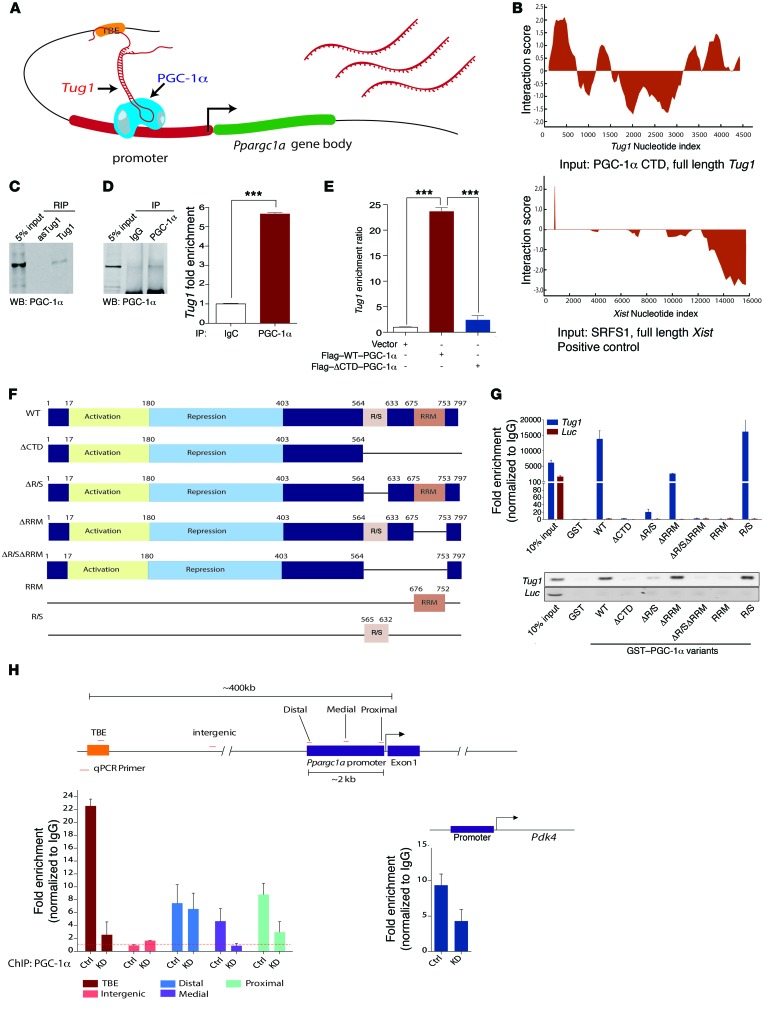

Tug1 interacts with an arginine/serine-rich region of the C-terminal domain ofPGC-1α. The identification of a unique TBE upstream of PGC-1α led us to investigate how the interaction between the TBE and Tug1 could regulate PGC-1α expression. We sought to determine whether Tug1, by binding to the TBE, could recruit PGC-1α protein to its own promoter, since it is known that PGC-1α enhances its own transcription via an autoregulatory loop (13, 22, 23) (Figure 7A). This idea was supported on the basis of the existence of 2 elements within the C-terminal domain (CTD) of PGC-1α, an RNA recognition motif (RRM), and an arginine/serine-rich (R/S) region, both of which are known to interact with RNA (32, 33). Bioinformatics analysis predicted that the CTD of PGC-1α could form potentially strong interactions with Tug1 (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Tug1 and PGC-1α directly interact to enhance Ppargc1a mRNA levels.

(A) Proposed model for the Tug1 mediated enhancement of Ppargc1a transcription. (B) Prediction of interaction propensity between the CTD and full length Tug1 RNA. Positive interaction score predicts increased propensity of binding. Control interaction plot (bottom panel) depicts experimentally validated interaction between the lncRNA Xist and its binding partner SRSF1. Positive Interaction Score indicates predicted binding. (C) Western blot (WB) analysis of podocyte nuclear extract incubated with sense or antisense biotinylated Tug1 demonstrating PGC-1α interaction with sense Tug1 RNA. (D) Western blot analysis confirming IP of endogenous PGC-1α from podocytes. qPCR analysis for Tug1 RNA in PGC-1α or IgG immunoprecipitated extracts. (E) qPCR analysis of RNA isolated from IP with Flag antibody from HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-tagged WT or the CTD deletion mutant (ΔCTD) PGC-1α. (F) Diagram of the GST PGC-1α variants used in domain mapping. (G) qPCR analysis of in vitro binding reactions using in vitro–transcribed Tug1 RNA or a luciferase RNA control incubated with the fusion protein constructs described in F. Agarose gel of qPCR products of Tug1 and luciferase. (H) Left: ChIP-qPCR analysis of PGC-1α in control WT (Ctrl) and Tug1-KD cells at the upstream TBE element, an intergenic region devoid of the predicted PGC-1α interaction, and the Ppargc1a gene promoter (primers spanning the distal, medial, and proximal regions of the promoter). Right: Positive control ChIP with primers designed to detect the promoter region of Pdk4. Data were fold-enrichment normalized to IgG. Cell culture experiments were repeated at least 3 times. ***P < 0.001, by 2-tailed Student’s t test (D). RNA-protein interaction scores were generated using catRAPID fragments software (33). ***P < 0.001, by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (E). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

To experimentally validate this prediction, we performed RNA IP using biotinylated sense and antisense Tug1 RNA mixed with nuclear extracts from cultured podocytes. Immunoblot analysis for PGC-1α revealed that sense, but not antisense, Tug1 interacts with PGC-1α (Figure 7C). We confirmed this result by performing the reciprocal IP using a biotin-conjugated PGC-1α antibody and measuring RNA transcript levels of Tug1 in PGC-1α-pulldown samples compared with IgG controls (Figure 7D). Furthermore, this interaction was visualized in cultured podocytes using combined FISH against Tug1 and immunofluorescence against PGC-1α (Supplemental Figure 9). Consistent with these observations, exogenous OE and pulldown of a Flag-tagged WT PGC-1α construct or a Flag-tagged construct harboring a CTD deletion (Flag–PGC-1α–ΔCTD) in HEK293T cells revealed that the CTD of PGC-1α is necessary for PGC-1α binding to Tug1 (Figure 7E). Next, we generated several glutathione S-transferase–tagged (GST-tagged) deletion constructs of the CTD of PGC-1α, along with GST-R/S or GST-RRM alone, to test which motif is necessary to mediate the Tug1–PGC-1α interaction (Figure 7F and Supplemental Figure 10). We observed that GST–PGC-1α–ΔCTD was unable to bind Tug1 compared with pulldown with a GST-WT–PGC-1α construct. GST-ΔRRM resulted in only a modest attenuation of Tug1 binding, while GST–PGC1α–ΔR/S and GST–PGC1α–ΔR/SΔRRM failed to bind to Tug1, implying that the R/S domain is necessary for the Tug1–PGC-1α interaction. In support of this notion, GST-R/S alone revealed robust binding to Tug1, whereas GST-RRM alone did not bind to Tug1 RNA (Figure 7G). ChIP of PGC-1α protein, followed by qPCR analysis, revealed substantial enrichment of the TBE element in Tug1 WT podocytes. In contrast, this enrichment was attenuated in Tug1-KD podocytes (Figure 7H). No enrichment was observed in an intergenic region located at the midpoint between the TBE and the PGC-1α TSS. ChIP-qPCR using primers against the promoter region of Ppargc1a itself and Pdk4, a well-described PGC-1α target, revealed a similar pattern of Tug1 regulation (Figure 7H). This pattern of PGC-1α binding was conserved for some (Pparg and Esrra) but not all of the PGC-1α target genes analyzed (Supplemental Figure 11). Taken together, these findings clearly indicate that Tug1 binds directly to an R/S-rich region of the CTD of PGC-1α, thereby regulating its activity.

Discussion

Here, we describe what we believe to be a previously unrecognized regulatory role of the Tug1/PGC-1α axis in the progression of DN. Our findings suggest that Tug1, a lncRNA, positively regulates Ppargc1a gene transcription and its target genes in podocytes. We also provide evidence indicating that Tug1 binds to an R/S-rich region of the CTD of PGC-1α. The binding of PGC-1α to the TBE helps to enhance Ppargc1a transcription.

PGC-1α is a well-characterized transcriptional coactivator that plays an integral role in maintaining energy homeostasis and mitochondrial biogenesis in response to a myriad of nutrient and hormonal signals (34, 35). While it is well established that PGC-1α expression levels and activity are regulated by a number of transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms, the role of lncRNAs in PGC-1α regulation was largely unknown. This study unexpectedly uncovered an additional layer of complexity of PGC-1α regulation through its interaction with Tug1. Our data suggest that the interaction between PGC-1α and Tug1 leads to enhanced Ppargc1a RNA expression, increased mitochondrial content, enhanced mitochondrial respiration, increased cellular ATP levels, and reduced mitochondrial ROS. Moreover, and through a series of biochemical studies, we found that the R/S domain is necessary for the binding of Tug1 to PGC-1α. Our results are not entirely surprising, since it has been previously shown that PGC-1α, through its R/S and RRM domains, can interact with several members of the transcriptional initiation, elongation, and splicing complexes to modulate and enhance the expression of its target genes (36, 37). However, it was unknown whether lncRNAs can bind to these domains and, importantly, what the functional consequences of such interactions are. We propose that Tug1 might be important in the autoregulatory action of PGC-1α by acting as a bridge between TBE, on the one hand, and the R/S domain of PGC-1α, on the other hand, to recruit PGC-1α to its own promoter, thereby enhancing its transcription.

Our laboratory and others have recently characterized the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in the progression of DN. Our results reinforce the importance of mitochondria as one of the key components of this complex and a major part of the multifactorial complications of diabetes (9, 10, 38, 39). This study underscores previous observations by our group and others that improving mitochondrial function, by targeting mitochondrial dynamics, activity, or numbers, is renoprotective in different models of kidney injury, including DN (12, 40–48). We provide evidence that PGC-1α is a mechanistic target of Tug1 in podocytes in the kidney, through which Tug1 regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics. We demonstrate that the inhibition of Tug1 alone, even in NG conditions, is sufficient to drive marked reductions in PGC-1α expression, whereas OE of Tug1 in HG conditions overcomes these events, resulting in significant improvements in several key elements of mitochondrial bioenergetics.

Perturbation of lncRNA expression in vivo, either by gain- or loss-of-function mutations, has begun to provide some insight into lncRNA function (49–52). However, there are only a limited number of mechanistic studies on the functions of lncRNAs in human pathologies, and there are no studies examining the functional role of lncRNAs in the kidney. In this regard, we believe our findings are important for the further understanding of the effect of lncRNA dysregulation in complex diseases such as DN in vivo. Ultimately, our data indicate that OE of Tug1 in podocytes in vivo mitigates the severity of several key parameters related to the progression of DN.

Recently, ChIRP-seq and similar approaches have been used to demonstrate that lncRNAs are able to physically bind DNA in a genome-wide fashion, partly through the presence of AG-purine–rich stretches acting as putative lncRNA-binding motifs (30, 53). In our own ChIRP-seq analysis, we found that the 2 most significantly enriched motifs within Tug1-binding sites resembled these motifs (Figure 5B). The functional consequences underlying this physical interaction are still relatively unexplored. However, in this study, we propose that the Tug1-binding site (TBE) serves as a genomic tether for Tug1, whereby Tug1 is able to bind and contribute to increased enrichment of PGC-1α at its own promoter. This finding is in line with several emerging lines of evidence suggesting that the interplay between lncRNAs and transcriptional coactivators constitutes an integral aspect of both their biological activities (54–57).

Interestingly, the biological activities of lncRNAs are also dictated in part by their localization in the cell (58, 59). Consistent with previously published data, our findings suggest that Tug1 localizes to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. While we have focused on the role of Tug1 in the nucleus in this study, it has been previously shown that cytoplasmic Tug1 could act as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) for certain miRs (60, 61), as well as play a role in the translational stability of mRNAs (62). Further studies are needed to unravel the cytoplasmic function of Tug1 in podocytes and the interplay between cytoplasmic versus nuclear Tug1 in regulating mitochondrial bioenergetics. Moreover, further studies are needed to determine how Tug1 is regulated in podocytes exposed to an HG milieu.

In conclusion, our study indicates that Tug1 interacts with PGC-1α at its promoter, resulting in elevated Ppargc1a transcriptional output. This model predicts that a decrease in Tug1 in the diabetic milieu would decrease PGC-1α expression, resulting in decreased expression of downstream PGC-1α targets involved in regulating mitochondrial bioenergetics. The fact that PGC-1α can be targeted by n lncRNA also opens new possibilities for potential genetic and pharmacological interventions to improve mitochondrial dysfunction in micro- and macrovascular complications of diabetes. Finally, this study provides further evidence for an important regulatory crosstalk between lncRNAs and mitochondria that could have broader relevance beyond the pathogenesis of DN.

Methods

Tissue culture.

Conditionally immortalized mouse podocytes, cultured as previously described, were a gift of Jochen Reiser (Department of Medicine, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA) (38). Briefly, cells were cultured on BD BioCoat Collagen I plates (BD Biosciences) at 33°C in the presence of 20 U/ml mouse recombinant IFN-γ (Sigma-Aldrich) to enhance expression of a thermosensitive T antigen. To induce differentiation, podocytes were maintained at 37°C without IFN-γ for 10 to 12 days. Podocytes prepared for experiments involving HG (25 mM) conditions were serum deprived for 24 hours prior to addition of HG. Likewise, control cells were serum deprived and cultured with NG (5 mM). Cell culture experiments were repeated at least 3 independent times. C2C12 (myoblast) and AML12 (hepatocyte) cell lines were obtained from ATCC.

Animal studies.

Diabetic mice (db/db) and their control littermates (db/m) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (strain BKS.Cg-Dock7m+/+ Leprdb/J). All mice used in the experiments were male. The ages of the mice are reported in the figure legends or figure panels. Mice used for the experiments were 24 weeks old, unless otherwise specified. No animals were excluded from the studies performed. All animals were maintained on a normal chow diet and housed in a room with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle and an ambient temperature of 22°C.

Transgenic mice.

The 4,716-bp Tug1-c isoform cDNA was PCR amplified from the IMAGE cDNA (clone ID 4223183; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cloned into a modified mammalian expression vector, pRK5 (63). Two oligonucleotides with aptamer S1, meant to mimic biotin and intended to retrieve transgenic Tug1 (64), were synthesized, annealed, and subcloned into the 3′ end of the Tug1 gene. The 2.5-kb human podocin promoter (hp2.5) was added to the 5′ end of the Tug1 gene, and the expression cassette was subcloned into a T2-Adapt8 transgenic vector harboring 2 copies of the HS4 insulator at both ends. The AscI-linearized Tug1 expression cassette was injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts at the Genetically Engineered Mouse Core at Baylor College of Medicine (http://www.bcm.edu/research/advanced-technology-core-labs/lab-listing/genetically-engineered-mouse/home.htm).

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeting.

The double-nickase/CRISPR technique was used to generate stable clones with KD of Tug1 in cultured podocytes. All guide RNAs were designed against sequences obtained from the mouse genome. Specifically, paired sgRNAs targeting the Tug1 upstream 250-bp promoter region or exon 3 (sg-1a/1b or sg-2a/2b; see Supplemental materials for the targeting sequence) were cloned into pX334 (Addgene) (65). These sgRNAs were also cloned into the 4-sgRNA–based multiplex system (Addgene) (66) for Tug1 KD or OE (see Supplemental Figure 3B for the construct design). To mutate (or delete) the TBE at the genomic level, 4 sgRNAs targeting different sites of the TBE gene were cloned into the aforementioned multiplex system. All constructs were sequence verified before transient transfection into undifferentiated podocytes using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Puromycin-resistant colonies were picked and analyzed for Tug1 or Ppargc1a expression levels by quantitative real time-PCR (qRT-PCR).

RNA IP.

The RNA IP (RIP) protocol was performed as previously described, with minor modifications (64, 67). To prepare the total cell lysate, podocytes at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml were cross-linked with 0.37% formaldehyde and lysed in 1 ml RIP lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 3 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma-Aldrich], and RNase inhibitor [New England BioLabs Inc.]) on ice for 10 minutes, and total cell lysate was obtained by centrifugation at 17,950 g for 15 minutes. To prepare the nuclear lysate, podocyte pellets were incubated with 2 packed cell volume (PCV) of cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 1× protease inhibitors cocktail) and subjected to dounce homogenization for complete (>95%) cell lysis. After centrifugation at 3,000 ×g for 10 minutes, the pellets were incubated with 2 PCV NETN buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 170 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, and 1× protease inhibitors cocktail) for sonication (30 seconds on, 59 seconds off, 15 times). Nuclear lysate was collected from the supernatant after ultracentrifugation at 200,000 ×g for 20 minutes at 4°C. For endogenous RIP assay using antibodies, biotin-labeled anti–PGC-1α (NBP1-04676B; Novus) or normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) was incubated with total lysate at 4ºC overnight, then Streptavidin Dynabeads M-280 (Thermo Fischer Scientific) were added and incubated for 2 hours. The beads were washed 5 times with 1 ml RIP wash buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 400 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 2% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 mM DTT). Protein-RNA complexes were eluted and treated with proteinase K at 45°C for 45 minutes. RNA samples were extracted with TRIzol, purified with a PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific), and detected by qRT-PCR. Fold enrichment was calculated from an RIP–qRT-PCR data analysis calculation shell (Sigma-Aldrich).

ChIRP.

ChIRP experiments were performed using a previously described protocol (30). A total of 44 antisense oligonucleotide biotinylated probes against Tug1 (1 probe per 100 bp RNA length) were designed using the Biosearch Technologies Stellaris FISH Probes online probe designer (singlemoleculefish.com). LacZ-specific probes were used as negative controls (See the Supplemental Table 1 for the probe sequences) (68). Briefly, 2 × 107 podocytes were cross-linked by incubating with 1% glutaraldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature and then lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, protease inhibitors cocktail, PMSF, and RNase inhibitor). The lysate was sonicated for 2 hours at 4°C with a Bioruptor (UCD-200; Diagenode) and incubated with biotinylated probes in hybridization buffer (750 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA, 15% formamide, protease inhibitors cocktail, PMSF, and RNase inhibitor) for 4 hours at 37°C. RNA-chromatin complexes were recovered by incubation with MyOne Streptavidin C1 Dynabeads (Thermo Fischer Scientific), and bead-associated RNA and DNA were purified and analyzed by qRT-PCR and qPCR, respectively.

Mitochondria functional assays.

Mitochondria were isolated from podocytes (cultured or freshly isolated from mouse kidneys) using the Mitochondria Isolation Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Mitochondria were assayed for complex activities, ATP production, oxygen consumption, or mitochondria DNA copy number (see Supplemental Methods for details). A fraction of the mitochondria was also subjected to protein extraction and SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblots of different complex subunits, using the Total OXPHOS Rodent WB Antibody Cocktail (ab110433; Abcam).

ChIRP-seq.

ChIRP DNA (10 ng) was prepared for Illumina sequencing as follows: 1) DNA samples were blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase and Klenow polymerase (New England BioLabs Inc.); 2) a dA base was added to the 3′ end of each strand by Klenow (exo minus) polymerase; 3) Illumina’s genomic adapters were ligated to the DNA fragments; 4) PCR amplification was performed to enrich ligated fragments; 5) after electrophoresis, products of approximately 200 to 400 bp were cut out from the gel and purified with a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). Completed library yields were quantified by the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. The libraries were denatured with 0.1 M NaOH to generate single-stranded DNA molecules, captured on an Illumina flow cell, and amplified in situ. The libraries were then sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 following the Illumina TruSeq Rapid SBS Kit protocol.

Statistics.

Group data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Comparisons of multiple groups were performed using 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Comparisons between 2 groups were performed using the Student’s t test. All tests were 2-tailed, with a P value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant. Tests were performed with GraphPad Prism, version 6.0b (GraphPad Software).

Study approval.

All animal studies were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines and were approved by the IACUC of the Institute of Biosciences and Technology of Texas A&M University Health Science Center (Houston, Texas, USA).

Accession numbers.

The RNA-seq (GSE77717), ChIRP-seq (GSE77493), and microarray (GSE77506) data discussed herein were deposited in and are accessible through the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO).

Author contributions

JL performed experiments, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript. SSB helped perform experiments and prepared the manuscript. ZY, YW, BAA, DLG, and NHG helped perform experiments and collect data. BHC helped generate Tug1-transgenic mice and edit the manuscript. PAO helped edit the manuscript, and FRD oversaw experiments, prepared the manuscript, and provided guidance on overall project design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants RO1 DK091310 and RO1 DK078900 (to FRD). Work performed by the UT-MDACC high-resolution microscopy facility was supported by institutional funds (Core grant CA16672). Flow cytometric data were generated at the UT-MDACC Flow Cytometry and Cellular Imaging Core Facility (NCI Cancer Center support grant P30CA16672). Microarray and ChIRP-seq analyses were performed by ArrayStar (Rockville, Maryland, USA). RNA-seq data were generated by the UT-MDACC Sequencing and Microarray Facility (Core grant CA016672 SMF). Chromogenic ISH was performed with assistance from the UT-MDACC Center for RNA Interference and Non-Coding RNAs (RGK Foundation).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Reference information:J Clin Invest. 2016;126(11):4205–4218. doi:10.1172/JCI87927.

See the related Commentary beginning on page 4072.

Contributor Information

Jianyin Long, Email: jlong1@mdanderson.org.

Zengchun Ye, Email: yzengch@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Yin Wang, Email: ywang44@mdanderson.org.

Paul A. Overbeek, Email: overbeek@bcm.tmc.edu.

Farhad R. Danesh, Email: danesh@bcm.edu.

References

- 1.Djebali S, et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012;489(7414):101–108. doi: 10.1038/nature11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huarte M. The emerging role of lncRNAs in cancer. Nat Med. 2015;21(11):1253–1261. doi: 10.1038/nm.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uchida S, Dimmeler S. Long noncoding RNAs in cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2015;116(4):737–750. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.302521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briggs JA, Wolvetang EJ, Mattick JS, Rinn JL, Barry G. Mechanisms of long non-coding RNAs in mammalian nervous system development, plasticity, disease, and evolution. Neuron. 2015;88(5):861–877. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JT. Epigenetic regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Science. 2012;338(6113):1435–1439. doi: 10.1126/science.1231776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. United States Renal Data System. U.S. Renal Data System Report (November 2015). National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/Pages/US-renal-data-system-report.aspx Accessed August 23, 2016.

- 8.Dugan LL, et al. AMPK dysregulation promotes diabetes-related reduction of superoxide and mitochondrial function. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(11):4888–4899. doi: 10.1172/JCI66218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang HM, et al. Defective fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat Med. 2015;21(1):37–46. doi: 10.1038/nm.3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinberg JM. Mitochondrial biogenesis in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(3):431–436. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010060643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma K, et al. Metabolomics reveals signature of mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(11):1901–1912. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo K, et al. Protective role of PGC-1α in diabetic nephropathy is associated with the inhibition of ROS through mitochondrial dynamic remodeling. PLoS One. 2015;10(4): doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hock MB, Kralli A. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:177–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin J, Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metab. 2005;1(6):361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arany Z, et al. Transcriptional coactivator PGC-1 alpha controls the energy state and contractile function of cardiac muscle. Cell Metab. 2005;1(4):259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin J, et al. Defects in adaptive energy metabolism with CNS-linked hyperactivity in PGC-1alpha null mice. Cell. 2004;119(1):121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leone TC, et al. PGC-1alpha deficiency causes multi-system energy metabolic derangements: muscle dysfunction, abnormal weight control and hepatic steatosis. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(4): doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Handschin C, et al. Abnormal glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle-specific PGC-1alpha knockout mice reveals skeletal muscle-pancreatic beta cell crosstalk. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(11):3463–3474. doi: 10.1172/JCI31785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehman JJ, Barger PM, Kovacs A, Saffitz JE, Medeiros DM, Kelly DP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(7):847–856. doi: 10.1172/JCI10268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin J, et al. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature. 2002;418(6899):797–801. doi: 10.1038/nature00904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arany Z, et al. The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1beta drives the formation of oxidative type IIX fibers in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2007;5(1):35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handschin C, Rhee J, Lin J, Tarr PT, Spiegelman BM. An autoregulatory loop controls peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha expression in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(12):7111–7116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232352100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hondares E, et al. Thiazolidinediones and rexinoids induce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-coactivator (PGC)-1alpha gene transcription: an autoregulatory loop controls PGC-1alpha expression in adipocytes via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivation. Endocrinology. 2006;147(6):2829–2838. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruas JL, et al. A PGC-1α isoform induced by resistance training regulates skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell. 2012;151(6):1319–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woroniecka KI, Park AS, Mohtat D, Thomas DB, Pullman JM, Susztak K. Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes. 2011;60(9):2354–2369. doi: 10.2337/db10-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalil AM, et al. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(28):11667–11672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904715106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang L, et al. ncRNA- and Pc2 methylation-dependent gene relocation between nuclear structures mediates gene activation programs. Cell. 2011;147(4):773–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patti ME, et al. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: Potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8466–8471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1032913100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mootha VK, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34(3):267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu C, Qu K, Zhong FL, Artandi SE, Chang HY. Genomic maps of long noncoding RNA occupancy reveal principles of RNA-chromatin interactions. Mol Cell. 2011;44(4):667–678. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9(9): doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hudson WH, Ortlund EA. The structure, function and evolution of proteins that bind DNA and RNA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(11):749–760. doi: 10.1038/nrm3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hertel KJ, Graveley BR. RS domains contact the pre-mRNA throughout spliceosome assembly. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30(3):115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finck BN, Kelly DP. PGC-1 coactivators: inducible regulators of energy metabolism in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(3):615–622. doi: 10.1172/JCI27794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 coactivators, energy homeostasis, and metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2006;27(7):728–735. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monsalve M, Wu Z, Adelmant G, Puigserver P, Fan M, Spiegelman BM. Direct coupling of transcription and mRNA processing through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Mol Cell. 2000;6(2):307–316. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallberg AE, Yamamura S, Malik S, Spiegelman BM, Roeder RG. Coordination of p300-mediated chromatin remodeling and TRAP/mediator function through coactivator PGC-1alpha. Mol Cell. 2003;12(5):1137–1149. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang W, et al. Mitochondrial fission triggered by hyperglycemia is mediated by ROCK1 activation in podocytes and endothelial cells. Cell Metab. 2012;15(2):186–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414(6865):813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chau BN, et al. MicroRNA-21 promotes fibrosis of the kidney by silencing metabolic pathways. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(121): doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ayanga BA, et al. Dynamin-related protein 1 deficiency improves mitochondrial fitness and protects against progression of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015101096. [published online ahead of print January 29, 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong YA, et al. Fenofibrate improves renal lipotoxicity through activation of AMPK-PGC-1α in db/db mice. PLoS One. 2014;9(5): doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu L, et al. Activation of FoxO1/ PGC-1α prevents mitochondrial dysfunction and ameliorates mesangial cell injury in diabetic rats. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;413:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao L, et al. Rap1 ameliorates renal tubular injury in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2014;63(4):1366–1380. doi: 10.2337/db13-1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan Y, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction and protects podocytes from aldosterone-induced injury. Kidney Int. 2012;82(7):771–789. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou Y, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α is renoprotective in doxorubicin-induced glomerular injury. Kidney Int. 2011;79(12):1302–1311. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tran M, et al. PGC-1α promotes recovery after acute kidney injury during systemic inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):4003–4014. doi: 10.1172/JCI58662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tran MT, et al. PGC1α drives NAD biosynthesis linking oxidative metabolism to renal protection. Nature. 2016;531(7595):528–532. doi: 10.1038/nature17184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gomez JA, et al. The NeST long ncRNA controls microbial susceptibility and epigenetic activation of the interferon-γ locus. Cell. 2013;152(4):743–754. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dimitrova N, et al. LincRNA-p21 activates p21 in cis to promote Polycomb target gene expression and to enforce the G1/S checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2014;54(5):777–790. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sauvageau M, et al. Multiple knockout mouse models reveal lincRNAs are required for life and brain development. Elife. 2013;2: doi: 10.7554/eLife.01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li L, Chang HY. Physiological roles of long noncoding RNAs: insight from knockout mice. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(10):594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mondal T, et al. MEG3 long noncoding RNA regulates the TGF-β pathway genes through formation of RNA-DNA triplex structures. Nat Commun. 2015;6: doi: 10.1038/ncomms8743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu X, et al. The retrovirus HERVH is a long noncoding RNA required for human embryonic stem cell identity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(4):423–425. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lanz RB, et al. A steroid receptor coactivator, SRA, functions as an RNA and is present in an SRC-1 complex. Cell. 1999;97(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80711-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hung T, et al. Extensive and coordinated transcription of noncoding RNAs within cell-cycle promoters. Nat Genet. 2011;43(7):621–629. doi: 10.1038/ng.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huarte M, et al. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell. 2010;142(3):409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mercer TR, Mattick JS. Structure and function of long noncoding RNAs in epigenetic regulation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(3):300–307. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fatica A, Bozzoni I. Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(1):7–21. doi: 10.1038/nri3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tan J, Qiu K, Li M, Liang Y. Double-negative feedback loop between long non-coding RNA TUG1 and miR-145 promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition and radioresistance in human bladder cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(20 Pt B):3175–3181. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cai H, et al. The long noncoding RNA TUG1 regulates blood-tumor barrier permeability by targeting miR-144. Oncotarget. 2015;6(23):19759–19779. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Heesch S, et al. Extensive localization of long noncoding RNAs to the cytosol and mono- and polyribosomal complexes. Genome Biol. 2014;15(1): doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-1-r6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin X, et al. PPM1A functions as a Smad phosphatase to terminate TGFbeta signaling. Cell. 2006;125(5):915–928. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kallen AN, et al. The imprinted H19 lncRNA antagonizes let-7 microRNAs. Mol Cell. 2013;52(1):101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339(6121):819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kabadi AM, Ousterout DG, Hilton IB, Gersbach CA. Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9-based genome engineering from a single lentiviral vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(19): doi: 10.1093/nar/gku749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tsai MC, et al. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329(5992):689–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trimarchi T, et al. Genome-wide mapping and characterization of Notch-regulated long noncoding RNAs in acute leukemia. Cell. 2014;158(3):593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.