Abstract

Previous refugee research has been unable to link pre-displacement trauma with unemployment in the host country. The current study assessed the role of pre-displacement trauma, post-displacement trauma, and the interaction of both trauma types to prospectively examine unemployment in a random sample of newly-arrived Iraqi refugees. Participants (N=286) were interviewed three times over the first two years post-arrival. Refugees were assessed for pre-displacement trauma exposure, post-displacement trauma exposure, a history of unemployment in the country of origin and host country, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression. Analyses found that neither pre-displacement nor post-displacement trauma independently predicted unemployment 2 years post-arrival; however, the interaction of pre and post-displacement trauma predicted 2-year unemployment. Refugees with high levels of both pre and post-displacement trauma had a 91% predicted probability of unemployment, whereas those with low levels of both traumas had a 20% predicted probability. This interaction remained significant after controlling for sociodemographic variables and mental health upon arrival to the U.S. Resettlement agencies and community organizations should consider the interactive effect of encountering additional trauma after escaping the hardships of the refugee's country of origin.

Keywords: unemployment, refugee, trauma, mental health, pre-displacement trauma, post-displacement trauma

Between 2007–2013, approximately 85,000 Iraqi refugees arrived in the U.S. (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2013). By definition, these refugees are escaping a war-torn region with an elevated risk of pre-displacement trauma. Among the most important challenges refugees face upon arrival in the host country is finding gainful employment. Surprisingly, research suggests the chances of employment have little to do with how severely refugees were traumatized in their country of origin (Schweitzer, Melville, Steel, & Lacharez, 2006; Teodorescu, Siqveland, Heir, Hauff, Wentzel-Larsen, & Lien, 2012), perhaps because resettlement in a new country offers the possibility of a fresh start free from the hardships of one's homeland. But what if refugees encounter additional trauma after arriving in the host country? Such post-displacement trauma after successfully escaping pre-displacement trauma could create emotional and psychological barriers to employment (e.g., demoralization; Parson, 1990), legal barriers to employment (e.g., police harassment and random arrests; Grabska, 2006), or pragmatic barriers to employment (e.g., insecure housing and therefore no permanent address; Yako & Biswas, 2014).

In a meta-analysis, Porter and Haslam (2005) found a robust relationship between poor refugee mental health and limited economic opportunities in the host country, suggesting that both pre-displacement factors, such as trauma exposure in the country of origin, and post-displacement factors, such as unemployment, contribute to poor mental health in refugees. Additionally, Hocking and colleagues (2015) found that refugees and asylum seekers who secured employment during the early post-displacement period reported better mental health and were exposed to less post-displacement stress when compared to their unemployed peers. When combined, these results suggest stress, trauma, and poor mental health may be the result of unemployment. However, what if this relationship is reciprocal or interactive? Specifically, pre-displacement trauma may be associated with additional trauma exposure and stress in the new country, contributing to unemployment, which then contributes to additional stress and continued unemployment. Indeed, researchers have suggested that pre and post-displacement trauma may interact to create additional stress and mental health problems for refugees (Teodorescu et al., 2012). To date, however, no study has specifically examined the impact of this “double” trauma exposure on an outcome integral to refugee mental health and survival—unemployment. The present study followed Iraqi refugees over a 2-year period to determine whether exposure to both pre-displacement trauma and post-displacement trauma predicts post-displacement unemployment 2 years after arrival in the U.S.

Method

Recruitment, Participants, and Procedures

Starting in 2010, a randomly selected, community-based sample of 298 newly-arrived Iraqi refugees was interviewed, on average, within one month of arrival (M months in U.S. = 1.17, SD = 1.15, range < 1 to 4.27 months) and then at 1-year intervals for 2 years. These three interviews are referred to as baseline, 1-year follow-up, and 2-year follow-up, respectively. All interviews were conducted orally in Arabic by an Arabic-English bilingual psychiatrist at a location of the participant's choosing (e.g., home, workplace, community center, etc.). Participants received a gift card as compensation for their participation in each interview.

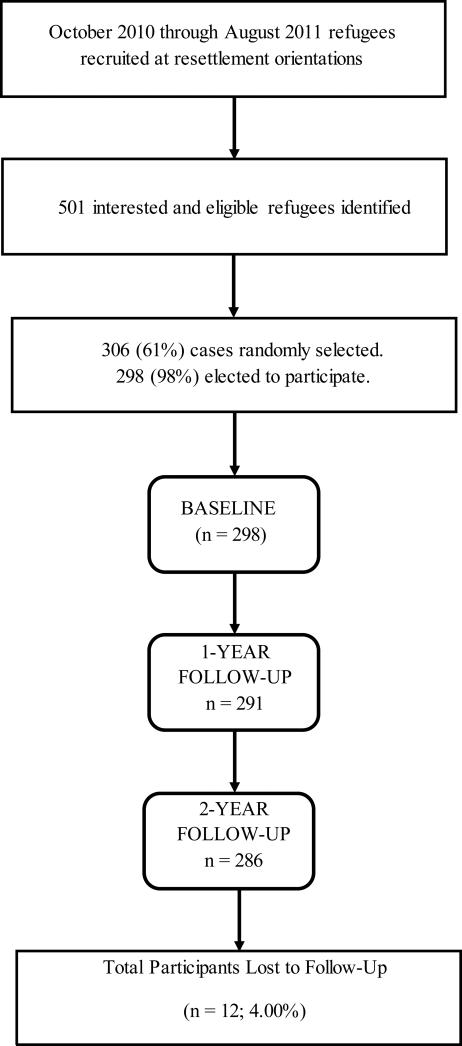

Refugees resettling in the U.S. must attend orientation meetings during the early post-arrival period. These mandatory meetings are organized and hosted by local resettlement agencies and are held on a regular basis (e.g., weekly, monthly), depending on the number of arrivals. During the 1-year recruiting period, a contact person at each resettlement agency notified the research team when orientation meetings with the newly-arrived refugees were held. An Arabic speaking member of the research team was present at each orientation meeting and provided an oral description of the research study. Any interested participants provided written consent for the researchers to contact them. A computer-generated random sample of 50-70% of those who were interested was selected each week, depending on the number of arrivals. Approximately 1,750 Iraqi refugees arrived in Michigan during the 1-year recruiting period (October 2010 through August 2011) (WRAPS, 2016). It should be noted, however, that not all Iraqi refugees resettling in Michigan were resettling in the Metro Detroit region. In total, out of 501 interested and eligible refugees, 306 (61%) were randomly selected for participation. These individuals were contacted by a member of the research team and given both oral and written information about the study; 98% of them (n=298) chose to participate and provided written consent to the protocol, which was approved by the Human Investigation Committee at Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan (IRB # 025509B3F). Across the three measurement waves, only 12 participants (4%) were lost to attrition; thus all sample descriptions and analyses refer to the sample of 286 refugees who were retained over time. Refer to Figure 1 for a visual depiction of this process.

Figure 1.

Recruitment, data collection, and attrition.

Measures

Pre-displacement trauma

Pre-displacement exposure to traumatic experiences and violence was measured at baseline using the traumatic event component of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ), Arabic version (Shoeb, Weinstein, & Mollica, 2007). This checklist of 39 pre-displacement trauma exposure items was specifically developed for use in an Iraqi refugee population and has been used in prior research examining Iraqi refugee mental health (e.g., Arnetz et al., 2014; Nickerson et al., 2014). Items were summed to create a cumulative pre-displacement trauma score with all refugees receiving a score ranging from 0 to 39. All items are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire for Pre-Displacement Trauma (N = 286)

| Traumatic event | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Oppressed because of ethnicity, religion, or sect | 261 (91.3) |

| Present while someone searched for people or things in your home | 95 (33.2) |

| Searched arbitrarily | 82 (28.7) |

| Property looted, confiscated, or destroyed | 110 (38.5) |

| Forced to settle in a different part of the country with minimal services | 231 (80.8) |

| Imprisoned arbitrarily | 9 (3.1) |

| Suffered ill health without access to medical care or medicine | 52 (18.2) |

| Suffered from lack of food or clean water | 46 (16.1) |

| Forced to flee your country or place of settlement | 258 (90.2) |

| Expelled from your country based on ancestral origin, religion, or sect | 4 (1.4) |

| Lacked shelter | 16 (5.6) |

| Witnessed the desecration or destruction of religious shrines or places of religious instruction | 191 (66.8) |

| Witnessed the arrest, torture, or execution of religious leaders or important members of tribe | 12 (4.2) |

| Witnessed execution of civilians | 37 (12.9) |

| Witnessed shelling, burning, or razing of residential areas or marshlands | 242 (84.6) |

| Witnessed or heard combat situation (explosions, artillery fire, shelling) or landmine | 278 (97.2) |

| Serious physical injury from combat situation or landmine | 11 (3.8) |

| Witnessed rotting corpses | 149 (52.1) |

| Confined to home because of chaos and violence outside | 278 (97.2) |

| Witnessed someone being physically harmed (beating, knifing, etc.) | 89 (31.1) |

| Witnessed sexual abuse or rape | 0 (0.00) |

| Witnessed torture | 8 (2.8) |

| Witnessed murder | 67 (23.4) |

| Forced to inform on someone placing them at risk of injury or death | 2 (0.7) |

| Forced to destroy someone's property | 2 (0.7) |

| Forced to physically harm someone (beating, knifing, etc.) | 2 (0.7) |

| Murder of violent death of family member (child, spouse) or friend | 163 (57.0) |

| Forced to pay for bulled used to kill family members | 0 (0.00) |

| Received the body of a family member and prohibited from mourning them and performing burial rights | 2 (0.7) |

| Disappearance of family member (child, spouse, etc.) or friend | 84 (29.4) |

| Kidnapping of family member (child, spouse, etc.) or friend | 164 (57.3) |

| Family member (child, spouse, etc.) or friend taken as hostage | 156 (54.5) |

| Someone informed on you placing you and your family at risk of injury or death | 116 (40.6) |

| Physically harmed (beaten, knifed, etc.) | 44 (15.4) |

| Kidnapped | 27 (9.4) |

| Taken as hostage | 20 (7.0) |

| Heard about frightening, dangerous events that occurred to someone else but that you did not experience yourself | 275 (96.2) |

| Sexually abused or raped | 0 (0.00) |

| Coerced to have sex for survival | 0 (0.0) |

Post-displacement trauma

Post-displacement exposure to traumatic experiences was measured at each interview. At baseline, refugees responded again to the 39 HTQ questions, but this time with a specific emphasis on experiences since arriving in the U.S. (i.e., “Since arriving in the U.S., have you lacked shelter?”). For the 1-year follow-up (37 questions) and 2-year follow-up (39 questions) participants responded to a modified version of the HTQ which replaced Iraq-relevant trauma items (e.g., “Serious physical injury due to combat situation or landmine”) with those that are more relevant for life in the U.S. (e.g., “Have you been in a car accident?”; “Have you been sexually harassed?”; “Has someone in your family had serious physical health problems?”). These items are listed in Table 3. To avoid double counting a traumatic event, at each follow-up assessment, participants responded only about traumatic events that occurred since the last assessment (e.g., “Since the last interview, have you been harassed by police?”). A cumulative post-displacement trauma score was created by summing items across all three interviews; scores ranged from 0 to 115.

Table 3.

Post-Displacement Trauma (U.S. Trauma Questionnaire) Over Time (N = 286)

| Baseline | 1st Follow-up | 2nd Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Oppressed because of ethnicity, sect, etc. | 0 (0) | 2 (.70) | 5 (1.7) |

| Present while property searched | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Searched arbitrarily | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (.30) |

| Property looted, confiscated, etc. | 0 (0) | 2 (.70) | 13 (4.5) |

| Forced to settle with minimal services | 0 (0) | 1 (.30) | 0 (0) |

| Imprisoned arbitrarily | 0 (0) | 1 (.30) | 0 (0) |

| Suffered ill health without medical care | 0 (0) | 1 (.30) | 54 (18.9) |

| Suffered from lack of food and water | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Forced to flee country | 0 (0) | ||

| Expelled from country | 0 (0) | ||

| Lacked shelter | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Witnessed desecration of religious shrines | 0 (0) | ||

| Witnessed arrest of religious leaders | 0 (0) | ||

| Witnessed execution of civilians | 0 (0) | ||

| Witnessed shelling, burning, etc. | 0 (0) | ||

| Witnessed or heard combat situation | 0 (0) | ||

| Serious injury from combat or landmine | 0 (0) | ||

| Witnessed rotting corpses | 1 (.30) | ||

| Confined to home because of violence | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Witnessed someone being harmed | 0 (0) | 1 (.30) | 0 (0) |

| Witnessed sexual abuse or rape | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Witnessed torture | 0 (0) | ||

| Witnessed murder | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Forced to inform on someone | 0 (0) | ||

| Forced to destroy someone's property | 0 (0) | ||

| Forced to physically harm someone | 0 (0) | ||

| Murder or violent death of family member | 1 (.30) | 1 (.30) | 1 (.30) |

| Forced to pay for bullets | 0 (0) | ||

| Received body of family member | 0 (0) | ||

| Disappearance of family member | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Kidnapping of family member | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Family member taken as hostage | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Someone informed on you | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Physically harmed | 0 (0) | 1 (.30) | 0 (0) |

| Kidnapped | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Taken as hostage | 0 (0) | ||

| Heard about frightening or dangerous events | 1 (.30) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sexually abused or raped | 0 (0) | ||

| Coerced to have sex for survival | 0 (0) | ||

| Seen person in U.S. who was violent | 0 (0) | 2 (.70) | |

| Family with mental health problems | 24 (8.4) | 52 (18.2) | |

| Family with health problems | 104 (36.4) | 134 (46.9) | |

| Family with legal troubles | 2 (.70) | 4 (1.4) | |

| Evicted or foreclosed on | 1 (.30) | 4 (1.4) | |

| Utilities turned off | 2 (.70) | 6 (2.1) | |

| Stress related to financial situation | 232 (81.1) | 211 (73.8) | |

| Worry about being deported | 9 (3.1) | 4 (1.40) | |

| Harassed by police | 4 (1.4) | 3 (1.0) | |

| Car accident | 14 (4.9) | 35 (12.2) | |

| Been imprisoned | 0 (0) | 2 (.70) | |

| Been arrested | 1 (.30) | 2 (.70) | |

| Coerced to do an illegal action for money | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Approached to do an illegal action for money | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Sexually harassed | 1 (.30) | 0 (0) | |

| Serious personal injury from assault | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Injured in another type of accident | 19 (6.6) | ||

| Core family unable to move to U. S. | 135 (47.2) | ||

Pre-displacement employment history

At baseline, all refugees were asked about their employment history prior to displacement. Refugees who reported working outside the home for pay (e.g., business owner, teacher, skilled worker, physician) were categorized as “employed,” whereas students, those working inside the home without pay, or those who identified as retired were categorized as “unemployed.”

Post-displacement employment

All refugees were unemployed upon arrival to the U.S. but were assessed for employment status at the 2-year follow-up. Refugees were specifically asked “Have you worked since coming to the U.S.?” with response alternatives of “Yes” and “No.” This measure of employment is conservative and does not capitalize on possible contextual or situational confounds (e.g., a refugee who quit her job in order to attend school full time).

English language ability

Proficiency in the host country language was assessed at 2-year follow-up. Participants responded to the following item on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree): “I feel that my English language skills are good enough for me to function in everyday U.S. life.” Single-item assessment of functional English language is consistent with prior refugee research (Nielsen, Jensen, Kreiner, Norredam, & Krasnik, 2015).

Mental health

Assessment of mental health at baseline was used to control for any possible differences in mental health upon arrival that may have affected the likelihood of securing gainful employment once in the host country.

Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms were assessed using the PTSD Checklist (PCL)—Civilian version (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 2006). The PCL demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .92) in this sample and is a reliable measure of PTSD symptoms in refugees (Arnetz, Rofa, Arnetz, Ventimiglia, & Jamil, 2013; Fodor, Pozen, Ntaganira, Sezibera, & Neugebauer, 2015).

Depression symptoms

Depression symptoms were assessed using the depression sub-scale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983). Chronbach's alpha for the subscale was good (.93). Previous research indicates the HADS depression subscale is a reliable measure of depression symptoms (Bjelland, Dahl, Haug, & Necklemann, 2002) and is a valid measure of depression symptoms in refugees (Ager, Malcom, Sadollah, & O'May, 2002).

Data Analysis

Attrition over time was very low. Of the original 298 participants, only seven were lost from baseline to 1-year follow-up (97.7% retention), and only five additional participants were lost from 1- to 2-year follow-up (96.0% retention rate over the three measurement waves; Figure 1). Hierarchal logistic regression was used to examine the role of pre-displacement trauma and post-displacement trauma on unemployment. In Step 1, sociodemographic variables were entered (i.e., gender, education, pre-displacement employment status, functional English language ability, and age). Mental health upon arrival to the host country was entered in Step 2 (i.e., PTSD and depression symptoms). For Step 3, both pre-displacement trauma and post-displacement trauma were entered individually. Finally, the interaction term (pre X post trauma) was included in Step 4. Gender, education, English language ability, age, and baseline mental health were included as control variables as they may influence employment status in the host country. All continuous variables were centered prior to analysis. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 23.0 with significance set to a 2-tailed p-value < .05.

Results

At the 2-year follow-up, 191 refugees (66.8%) reported being employed, and 95 refugees (33.2%) reported being unemployed. Other demographic items, mental health symptoms, and cumulative trauma information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, trauma exposure, and mental health information for newly-arrived Iraqi refugees (N=286)

| M (SD) | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 131 (45.80) | |

| Male | 155 (54.20) | |

| Baseline Education | ||

| High School or Less | 205 (71.70) | |

| Greater than High School | 81 (28.30) | |

| Religious Affiliation | ||

| Christian | 263 (92.00) | |

| Muslim | 20 (7.00) | |

| Mandia | 3 (1.00) | |

| Employment Status Pre-displacement | ||

| Employed | 154 (53.8) | |

| Unemployed | 132 (46.2) | |

| Employment Status at 2-year Follow-up | ||

| Employed | 191 (66.80) | |

| Unemployed | 95 (33.20) | |

| Age (years) | 33.35 (11.41) | |

| English language abilitya | 2.72 (.99) | |

| Baseline PTSD symptomsb | 19.47 (5.48) | |

| Baseline Depression symptomsc | 1.87 (3.50) | |

| Cumulative pre-displacement traumad | 12.56 (3.47) | |

| Cumulative post-displacement traumae | 3.83 (2.00) |

Single-item English language ability ranging from 1 to 5 with higher scores indicating greater functional English language.

PTSD symptoms assessed using the PCL-C. Theoretical range from 17 to 85 with higher scores reflecting greater PTSD symptoms.

Depression symptoms assessed using the HADS Depression subscale. Theoretical range from 0 to 21 with higher scores reflecting greater depression symptoms.

Calculated by summing all pre-displacement trauma items. Scores could range from 0 to 39.

Calculated by summing all post-displacement trauma items. Scores could range from 0 to 115.

Of specific interest, the most frequently reported pre- and post-displacement traumas are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Nearly all refugees reported that, while in Iraq, they experienced oppression because of their religion or sect, witnessed combat, and were confined to their homes because of violence (Table 2). Additionally, over half of the refugees reported witnessing rotting corpses and having a family member or friend who was murdered, kidnapped, or taken hostage. Post-displacement trauma exposure, presented in Table 3, was notably less common than pre-displacement trauma exposure. However, many refugees reported family members with mental or physical health problems, high stress related to their financial situation, suffering ill health due to an inability to access healthcare, and having core family members who were unable to move to the U.S. Some refugees also reported serious physical traumas (e.g., injuries due to accidents) and being victims of crimes (e.g., property looted) (Table 3).

Neither pre-displacement trauma nor post-displacement trauma alone predicted employment status 2 years after arrival to the U.S. (Step 3, Table 4). However, inclusion of the interaction of pre- and post-displacement trauma in Step 4 significantly improved model fit (χ2=5.41, df = 1, N =284, p =.02). In Step 4, gender (being female), age (being older), and functional English language ability (worse English) significantly predicted unemployment two years post-arrival. The trauma-by-trauma interaction, however, remained significant after controlling for these sociodemographic variables as well as pre-displacement employment history and mental health upon arrival to the host country (β = .05, Wald χ2 = 4.19, OR = 1.05, p=.04). Step 4 correctly classified 87% of the employed refugees and 61% of the unemployed refugees (78.5% total cases correctly classified). Additionally, Step 4 explained 42.7% of the variance in employment status (Nagelkerke R2 = .427).

Table 4.

Logistic regression predicting unemployment in Iraqi refugees two-years after arrival to the U.S. (N=284)

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Wald | OR | β | Wald | OR | β | Wald | OR | β | Wald | OR | |

| Constant | −1.86 | 40.78 | .16*** | −1.87 | 40.72 | .16*** | −1.82 | 36.88 | .16*** | −1.91 | 39.03 | .15*** |

| Gendera | 1.19 | 8.54 | 3.92** | 1.20 | 8.61 | 3.33** | 1.17 | 8.01 | 3.22** | 1.24 | 8.60 | 3.43** |

| Educationb | .48 | 1.50 | 1.62 | .50 | 1.62 | 1.65 | .51 | 1.64 | 1.66 | .45 | 1.23 | 1.56 |

| Pre-Displacement Employmentc | .37 | .78 | 1.45 | .36 | .72 | 1.44 | .31 | .49 | 1.36 | .33 | .54 | 1.39 |

| Language Abilityd | −.84 | 16.48 | .43*** | −.82 | 15.77 | .44*** | −.81 | 15.16 | .44*** | −.82 | 15.40 | .44*** |

| Age | .08 | 24.60 | 1.08*** | .07 | 22.83 | 1.08*** | .07 | 22.72 | 1.08*** | .08 | 24.19 | 1.08*** |

| Baseline PTSDe | .02 | .22 | 1.02 | .02 | .31 | 1.02 | .02 | .33 | 1.02 | |||

| Baseline Depressionf | .01 | .05 | 1.01 | .02 | .10 | 1.02 | −.01 | .05 | .99 | |||

| Pre-Displacement Traumag | −.03 | .40 | .97 | −.05 | .80 | .96 | ||||||

| Post-Displacement Traumah | .01 | .01 | 1.00 | .06 | .40 | 1.06 | ||||||

| Pre X Post Trauma Interaction | .05 | 4.19 | 1.05* | |||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2i | .405 | .407 | .409 | .427 | ||||||||

| χ 2 | 97.90*** | .53 | .40 | 5.41** | ||||||||

| df | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

Note: β = logistic regression coefficient; Wald = Wald χ2; OR = odds ratio. Employment status coded such that 0 = employed and 1 = unemployed. All continuous variables were centered prior to analysis. N=284 due to two refugees with missing scores on a covariate.

Reference = male

Reference =≤ high school

Reference = working

Single-item English language ability ranging from 1 to 5 with higher scores indicating greater functional English language.

Baseline PTSD assessed using the PCL-C. Theoretical range from 17 to 85 with higher scores reflecting greater PTSD symptoms.

Baseline Depression assessed using the HADS Depression subscale. Theoretical range from 0 to 21 with higher scores reflecting greater depression symptoms.

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) range from 0 to 39.

U.S. Trauma Questionnaire range from 0 to 115.

Denotes percentage of variance explained.

p <.05

p <.01

p <.001

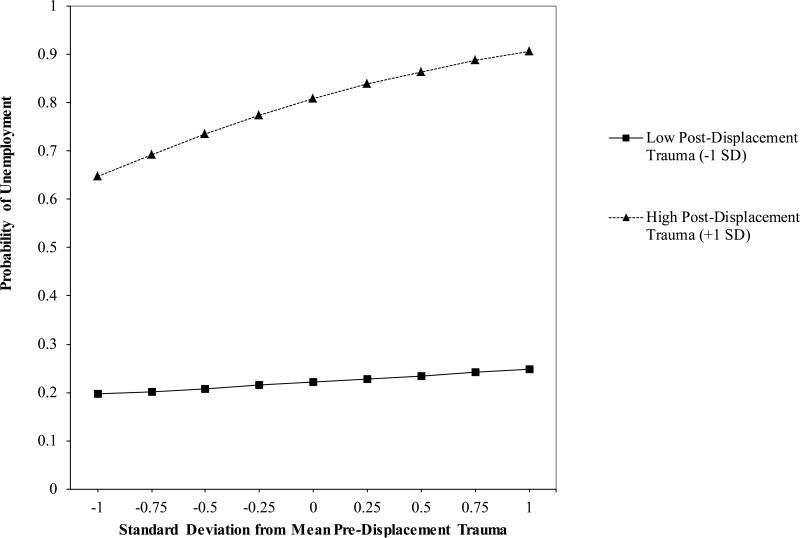

Those who experienced both high pre-displacement trauma and high post-displacement trauma had the highest predicted probability of unemployment (91%) two years post-arrival, whereas those low in both pre and post-displacement trauma had only a 20% predicted probability of unemployment. These results have been graphed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Post-displacement trauma moderates the effect of pre-displacement trauma on unemployment in Iraqi refugees two years after arrival to the U.S. For graphing purposes, “Low” values for continuous predictors are calculated at −1 standard deviation and “High” values are calculated at +1 standard deviation. All calculations include control variables gender, education, pre-displacement employment status, functional English language ability, age, and baseline mental health.

Discussion

For this Iraqi refugee sample, neither pre-displacement trauma nor post-displacement trauma alone predicted employment status two years after arriving in the U.S.; however, the interaction of these two distinct stressors was predictive of employment status. Importantly, this trauma-by-trauma interaction was significant after controlling for sociodemographic variables including education, mental health upon entering the host country, and pre-displacement employment status. These findings not only echo but also explain the puzzling prior reports that high pre-displacement trauma tells little about employment potential in the host country (Schweitzer et al., 2006; Teodorescu et al., 2012). High pre-displacement trauma predicts unemployment, but only for those who also experience high post-displacement trauma.

The Unemployment and Trauma Cycle

Prior research has noted that refugees are at a heightened risk for violence and trauma compared to their host country peers (Klat, Hossani, Kiss, & Zimmerman, 2013), yet the effects of this “double exposure trauma” on refugees are relatively unknown. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study indicating that a combination of pre and post-displacement trauma may contribute to unemployment in a refugee population. Although the impact of unemployment on life stress and health has been well-documented (Liem & Rayman, 1982; Paul & Moser, 2009; Rotenberg, Kutsay, & Venger, 2000), exactly how the stress and unemployment cycle begins in refugees remains unclear. Once the cycle begins, however, the relationship between certain life stressors, unemployment, and mental health may be interdependent (Gallie, Paugam, & Jacobs, 2003; Hocking et al., 2015). Unemployment itself is a stressor, but in the present Iraqi refugee sample, it appears also to result from stressors, specifically the amalgam of pre and post-displacement traumas. It is possible that such a combination creates demoralization (Parson, 1990), psychological impairment (Paul & Moser, 2009), or serves to otherwise interrupt or prevent the behaviors needed to gain employment in the host country.

Examination of the individual post-displacement traumatic events could offer insight as to how these traumas contribute to unemployment. Refugees frequently have high healthcare needs (Gerritsen et al., 2006) and an inability to access healthcare exacerbates these chronic health conditions (Correa-Velez, Johnson, Kirk, & Ferdinand, 2008). In the U.S., refugees are provided healthcare insurance during the first eight months and they report high utilization of healthcare during the first year of arrival (Elsouhag, et al., 2015). However, refugees report significantly reduced health care utilization after this subsidized insurance is terminated (Wright et al, 2015). This decline in health care utilization likely occurs because alternative health care programs, such as individual health insurance, are costly. In the current study, nearly one-fifth of the refugees reported poor health due to lack of access to medical care between the first and second year post-arrival. These results suggest an inability to access healthcare and manage chronic health conditions may be contributing to a history of unemployment in the host country. Additionally, as Table 3 indicates, many refugees had family members with mental and physical health problems. These refugees may be responsible for physical care of the ill family member and, thus, unable to work outside the home. However, the stigma associated with poor mental health in Middle Eastern cultures should also be noted (Ciftci, Jones, & Corrigan, 2012; Kulwicki, 2002). This cultural shame and stigma applies not only to the individuals experiencing the mental illness, but also to their families (Youssef & Deane, 2006). As such, the trauma of a mentally-ill family member may contribute to the refugee's own poor mental health, demoralization, and unemployment. Finally, many refugees reported distress due to their financial situation at 1-year and 2-year follow-ups. This finding supports extensive research linking unemployment with subsequent financial distress (e.g., Paul & Moser, 2009). However, research has found that financial insecurity and poverty actually contribute to continued unemployment, and that financial distress decreases the likelihood that an individual will enter the workforce (Gallie, Paugam, & Jacobs, 2003). Given this, we suggest the financial distress seen in the current study may be the result of unemployment and contribute to a continued trajectory of unemployment in the host country.

Limitations and Future Directions

The World Health Organization has noted the paucity of research examining unemployment longitudinally and the lack of research examining the effects of migration on unemployment (Benach, Mutaner, & Santana, 2007). The current study helps fill these gaps by assessing newly-arrived Iraqi refugees and following them over a 2-year period. Yet, despite the longitudinal nature of the current study and the high retention rate across the three measurement waves, more research is necessary. The relationship between unemployment and poor mental health has been previously identified (e.g., Paul & Moser, 2009). However, a complex relationship between trauma, unemployment, and mental health appears to exist. It may be that unemployment exposes individuals to higher rates of traumatic experiences, which then contribute to poorer mental health over time. If so, future research should look for a decline in post-displacement trauma exposure and a decline in mental health symptoms once refugees secure gainful employment. Identifying such a relationship would suggest a causal link between trauma exposure, unemployment, and mental health. Additionally, the current study examined individuals who were granted refugee status upon arrival to the host country. However, research suggests visa status may impact mental health during the post-displacement period (Hocking et al., 2015; Silove et al., 1998). Future research should consider the impact of secure versus insecure visa status when considering post-displacement trauma, mental health, and unemployment. Furthermore, future research should follow the unemployment status of refugees over the next 5 to 10 years. Results from the current study indicate chronic or lifetime unemployment for refugees could begin within a few years post-arrival. Yet, it may also be that some refugees require longer than 2 years to develop the language and job skills necessary to secure employment in the host country. If so, future research should examine not only changes in job status for these unemployed refugees but also causes of those changes in job status (e.g., increased host country language ability, new degree or training, etc.). Finally, the current study dichotomized post-displacement employment status. This method should prove robust against spurious findings given that a refugee working for any period of time during the 2-year study period was considered employed. However, future research should consider more continuous measures of employment such as hours worked per week or length of employment.

Results from the current study suggest that successful integration of refugees into the host country is a continuous and dynamic process. Refugees may enter the host country with pre-displacement trauma exposure. Yet, our results and those of others (e.g., Porter & Haslam, 2005; Hocking et al., 2015) suggest that post-displacement factors, such as discrimination, limited access to health care, and poor economic opportunities, are critical to understanding refugee mental health. Escaping the hardships of the country of origin is not the last “hurdle” that refugees face, because many refugees experience additional trauma and stress once in the host country. As such, refugee resettlement agencies and host countries should focus resources on decreasing additional trauma exposure in the early post-arrival period. Although the average post-displacement trauma exposure was relatively low compared to the average number of pre-displacement trauma experiences, results indicate that even the relatively few post-displacement traumatic experiences have an impact. Results from the current study suggest that if refugee resettlement agencies, community organizations, and host countries can work to decrease even a few of these traumatic experiences, then the likelihood of securing gainful employment improves significantly.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, award number R01MH085793) and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P30ES020957). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIMH, nor NIEHS. The authors wish to thank Yousif Talia, M.D., Evone Barkho, M.D., MPH, and Monty Fakhouri, M.S., for their work in collecting data and Mrs. Raja Yaldo for her help with data entry. Sincere thanks to Lutheran Social Services of Michigan, The Kurdish Human Rights Watch, and the Catholic Services of Macomb County for their assistance in participant recruitment. The authors also extend their gratitude to the refugees who participated in this study.

References

- Ager A, Malcom M, Sadollah S, O'May F. Community contact and mental health amongst socially isolated refugees in Edinburgh. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2002;15:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz BB, Broadbridge CL, Jamil H, Lumley MA, Pole N, Barkho E, Fakhouri M, Talia YR, Arnetz JA. Specific trauma subtypes improve the predictive validity of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire in Iraqi refugees. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2014;16:1055–1061. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-9995-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz JE, Rofa, Yoasif, Arnetz BB, Ventimiglia M, Jamil H. Resilience as a protective factor against the development of psychopathology among refugees. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2013;201:167–172. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182848afe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benach J, Mutaner C, Santana V. Employment conditions and health inequalities: A final report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2007. [June 17, 2015]. from http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/articles/emconet_who_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Necklemann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research Therapy. 2006;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciftci A, Jones N, Corrigan PW. Mental health stigma in the Muslim community. Journal of Muslim Mental Health. 2013;7:17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Velez I, Johnson V, Kirk J, Ferdinand A. Community-based asylum seekers' use of primary health care services in Melbourne. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2008;188:344–348. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsouhag D, Arnetz BB, Jamil H, Lumley MA, Broadbridge CL, Arnetz J. Factors associated with healthcare utilization among Arab Immigrants and Iraqi Refugees. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2015;17:1305–1312. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0119-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodor KE, Pozen J, Ntaganira J, Sezibera V, Neugebauer R. The factor structure of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among Rwandans exposed to the 1994 genocide: A confirmatory factory analytic study using the PCL-C. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2015;32:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallie D, Paugam S, Jacobs S. Unemployment, poverty, and social isolation: Is there a vicious cycle of social exclusion? European Studies. 2003;5:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen AA, Bramsen I, Devillé W, van Willigen LH, Hovens JE, van der Ploeg HM. Physical and mental health of Afghan, Iranian and Somali asylum seekers and refugees living in the Netherlands. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41:18–26. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabska K. Marginalization in urban spaces of the global south: Urban refugees in Cairo. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2006;19:287–307. [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Kennedy GA, Sundram S. Social factors ameliorate psychiatric disorders in community-based asylum seekers independent of visa status. Psychiatry Research. 2015;230:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klat A, Hossani M, Kiss L, Zimmerman C. Asylum seekers, violence, and health: A systematic review of research in high income host countries. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:E30–E42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulwicki AD. The practice of honor crimes: A glimpse of domestic violence in the Arab world. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2002;23:77–87. doi: 10.1080/01612840252825491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem R, Rayman P. Health and social costs of unemployment. American Psychologist. 1982;37:1116–1123. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.37.10.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson A, Liddell BJ, Maccallum F, Steel Z, Silove D, Bryant RA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and prolonged grief in refugees exposed to trauma and loss. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen SS, Jensen NK, Kreiner S, Norredam M, Krasnik A. Utilisation of psychiatrists and psychologists in private practice among non-Western labor immigrants, immigrants from refugee-generating countries and ethnic Danes: the role of mental health status. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2015;50:67–76. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0916-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parson ER. Post-traumatic demoralization syndrome (PTDS). Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 1990;20:17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Paul KI, Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009;74:264–282. [Google Scholar]

- Porter M, Haslam N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:602–612. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg V, Kutsay S, Venger A. The subjective estimation of integration into a new society and the level of distress. Stress Medicine. 2000;16:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Melville F, Steel Z, Lacharez P. Trauma, post-migration living difficulties, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment in resettled Sudanese refugees. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40:179–187. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoeb M, Weinstein H, Mollica R. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: Adapting a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Iraqi refugees. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2007;53:447–463. doi: 10.1177/0020764007078362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove D, Steel Z, McGorry P, Mohan P. Trauma exposure, post migration stressors, and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress in Tamil asylum seekers: comparison with refugees and immigrants. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1998;97:175–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb09984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu D, Heir T, Hauff E, Wentzel-Larsen T, Lien L. Mental health problems and post-migration stress among multi-traumatized refugees attending outpatient clinics upon resettlement to Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2012;53:316–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu D, Siqveland J, Heir T, Hauff E, Wentzel-Larsen T, Lien L. Posttraumatic growth, depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, post-migration stressors and quality of life in multi-traumatized psychiatric outpatients with a refugee background in Norway. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012;10:84. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) [June 17, 2015];Iraqi Refugee Processing: Fact Sheet. 2013 from http://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-asylum/refugees/iraqi-refugee-processing-fact-sheet.

- Department of State US. [February 29, 2016];Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM), Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS) from http://www.wrapsnet.org/Reports/AdmissionsArrivals/tabid/211/language/en-US/Default.aspx.

- Wright AM, Aldhalimi A, Lumley MA, Pole N, Jamil H, Arnetz JE, Arnetz BB. Determinants of resource needs and utilization among refugees over time. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1121-3. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yako RM, Biswas B. “We came to this country for the future of our children. We have no future”: acculturative stress among Iraqi refugees in the United States. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2014;38:133–14. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef J, Deane FP. Factors influencing mental-health help-seeking in Arabic-speaking communities in Sydney, Australia. Mental Health, Religion, and Culture. 2006;9:43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]