Abstract

Objective

To determine whether racial and ethnic differences exist among patients with similar access to care, we examined outcomes after heart failure hospitalization within a large municipal health system.

Background

Racial and ethnic disparities in heart failure outcomes are present in administrative data, and one explanation is differential access to care.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of 8,532 hospitalizations of adults with heart failure at 11 hospitals in New York City from 2007 to 2010. Primary exposure was ethnicity/race, and outcomes were 30- and 90-day readmission and 30-day and one-year mortality. Generalized estimating equations were used to test for association between ethnicity/race and outcomes with covariate adjustment.

Results

Of included hospitalizations, 4,305 (51%) were for blacks, 2,449 (29%) were for Hispanics, 1,494 (18%) were for whites, and 284 (3%) were for Asians. Compared to whites, blacks and Asians had lower one-year mortality, with adjusted odds ratios (aORs) 0.75 (95% CI 0.59–0.94) and 0.57 (95% CI 0.38–0.85), whereas Hispanics were not significantly different (aOR 0.81: 95% CI 0.64–1.03). Hispanics had higher odds of readmission than whites, with aORs 1.27 (95% CI 1.03–1.57) at 30 days and 1.40 (95% CI 1.15–1.70) at 90 days. Blacks had higher odds of readmission than whites at 90 days (aOR 1.21: 95% CI 1.01–1.47).

Conclusions

Racial and ethnic differences in outcomes after heart failure hospitalization were present within a large municipal health system. Access to a municipal health system may not be sufficient to eliminate disparities in heart failure outcomes.

Keywords: Race and Ethnicity, Heart Failure, Health Disparities, Morbidity/Mortality, Outcomes Research

Introduction

Racial and ethnic health disparities are a significant problem in the United States, and eliminating disparities is a public health priority (1). Racial and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease care and outcomes persist after controlling for socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and disease severity (2–4). Disparities are common in heart failure, a condition that affects 6 million Americans and remains a frequent cause of hospitalization and mortality (5, 6).

Epidemiologic studies from the 1970s–80s suggest that black patients with heart failure have higher or similar mortality and higher hospitalization rates compared to white patients (7–9). In more recent administrative and registry data, black and Hispanic patients are more likely than white patients to be hospitalized for heart failure but have lower short-term mortality (10–15). Of these studies, only two included non-Medicare patients (10, 14), and only one adjusted for both socioeconomic and clinical variables (13). Hospitalizations and short-term mortality are decreasing overall for Medicare patients with heart failure, but disparities in outcomes between black and white patients are widening (15). Although less studied, Asian Americans with heart failure have similar or lower mortality and similar rates of hospitalization compared to whites (10, 13, 14). Despite evidence that racial and ethnic disparities persist after controlling for socioeconomic status, it is not clear whether disparities arise at the level of patients, health care providers, or health systems (1, 16, 17).

Differences in access and quality of care may partially explain the discordance between hospitalization and mortality rates in minority patients compared to white patients (10, 18). Black and Hispanic patients tend to receive care at poorer-performing hospitals (19, 20) and have worse access to outpatient care (21). Hospitals with higher proportions of black or Hispanic Medicare patients have higher risk-adjusted heart failure readmission rates and greater racial and ethnic disparities than hospitals that primarily serve white patients (22, 23). The extent to which racial and ethnic differences exist among patients with heart failure within an urban healthcare system is unknown. The purpose of this study was to determine the magnitude of racial and ethnic differences in outcomes after heart failure hospitalization among patients admitted to the municipal health system in New York City. We studied this diverse population with similar access to care to determine whether access to care eliminates racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes.

Methods

We studied outcomes after heart failure acute care hospitalization stratified by racial and ethnic group in a retrospective cohort of adults hospitalized between 2007 and 2010 within New York City Health and Hospital Corporation (HHC), the largest municipal healthcare system in the United States. HHC includes 11 acute care hospitals, four skilled nursing facilities, six diagnostic and treatment centers, and more than 70 community clinics (24). The NYU School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this research.

The data sources were the HHC clinical data warehouse, the New York Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS), and the New York Vital Statistics registry. Demographic and clinical data were obtained from the HHC data warehouse, which is derived from the electronic health record. We obtained hospitalization details including discharge diagnosis and readmission from SPARCS, a registry of all acute non-federal hospitalizations in New York. Post-discharge mortality was determined from the Vital Statistics registry, which contains all deaths in the state. These three datasets were linked using a stepwise deterministic approach with patient identifiers.

We included acute care hospitalizations for heart failure within HHC hospitals of adults age 18 and older between 1/2/2007 and 9/30/2010. Heart failure was defined as principal discharge diagnosis ICD-9-CM code 428. Hospitalizations in which the patient died or was discharged to hospice were excluded. The primary exposure was the patient’s ethnicity/race. Ethnicity and race were self-reported by patients and recorded by the admitting hospital. For patients whose hospital-recorded race and ethnicity were missing or listed as other or unknown, state-reported data was used. Patients were categorized as Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic Asian. Due to small sample size, we excluded patients whose race was American Indian/Alaska Native, other, or unknown.

Outcomes included 30-day mortality, one-year mortality, hospital readmission within 30 days, and hospital readmission within 90 days. Demographic variables included age and sex. Utilization and access variables included clinic visits and hospitalizations within HHC for 90 days prior to admission. Insurance status was categorized as Medicare, Medicaid, private, uninsured, and other insurance. Socioeconomic variables were estimated at the neighborhood level using ZIP code level data from the US Census Bureau’s 2009 American Community Survey and included median household income and percent high school graduates. Clinical variables included systolic blood pressure, heart rate, creatinine, and hemoglobin on admission. Comorbid conditions were based on discharge diagnoses using standard algorithms (25) and included diabetes, chronic kidney disease, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignancy, and dementia.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square test was used to test for differences in categorical variables among racial/ethnic groups. Analysis of Variation (ANOVA) was used to test for differences in continuous variables among racial/ethnic groups. Unadjusted mortality and readmission rates were reported by race/ethnicity and compared across categories using chi-square tests. To account for correlation related to repeat hospitalizations, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) to test for association between race/ethnicity and outcomes. We developed two GEE models: the first was an unadjusted model, and the second adjusted for all covariates as defined above, including demographics, utilization/access variables, insurance status, socioeconomic status, clinical variables, and comorbid conditions, and included a fixed-effect for the HHC hospital to which the patient presented.

We performed a secondary analysis in which we examined the outcome of total days that patients were alive and out of the hospital during the year after index hospitalization (26). We presented this outcome as means with 95% confidence intervals and calculated hazard ratios using adjusted Cox proportional hazard models. For this analysis, we only used the first hospitalization for each patient.

All tests were evaluated at a 2-sided significance level of p<0.05. STATA version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for all analyses.

Results

There were 8,532 heart-failure hospitalizations that met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these, 4,305 (51%) were for black patients, 2,449 (29%) were for Hispanic patients, 1,494 (18%) were for white patients, and 284 (3.3%) were for Asian patients (Table 1). This cohort included 5,108 unique patients. The mean age was 67±14 years old, and 48% of patients were female. White patients were the oldest with a mean age of 77±13 years compared to 65±14 years for all other patients (p<0.0001). In terms of insurance, 36% of patients had Medicare, 28% had Medicaid, and 16% had no insurance. Compared to white patients, black, Hispanic, and Asian patients were more likely to have Medicaid or be uninsured and less likely to have Medicare (p<0.0001). Comorbid conditions were common and all differed significantly by race/ethnicity (Table 1). For instance, Hispanic and Asian patients had higher rates of diabetes and chronic kidney disease compared to white and black patients (p<0.0001). White patients had the highest rates of myocardial infarction and dementia (p<0.0001). Black patients had the highest systolic blood pressure and heart rate on admission (p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Heart Failure Hospitalization Patient Characteristics by Race/Ethnicity (N=8,532)

| White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF Hospitalizations | 1494 (18%) | 4305 (51%) | 2449 (29%) | 284 (3%) | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Mean Age±SD | 76.6±12.7 | 63.2±14.7 | 67.8±13.6 | 67.9±12.6 | <0.0001 |

| Age 18–50 | 3.1% | 18.8% | 9.4% | 6.3% | <0.0001 |

| Age 50–65 | 15.6% | 36.4% | 30.2% | 29.6% | |

| Age 65–80 | 32.4% | 29.0% | 39.9% | 45.1% | |

| Age >80 | 48.9% | 15.8% | 20.5% | 19.0% | |

| Female | 49.9% | 49.1% | 44.3% | 47.5% | <0.0001 |

| Access/Utilization | |||||

| Clinic within prior 90days | 11.5% | 18.7% | 20.8% | 25.7% | <0.0001 |

| Hosp. within prior 90 days | 30.8% | 22.6% | 25.5% | 23.6% | <0.0001 |

| Insurance Type | |||||

| Medicaid | 15.5% | 32.5% | 27.7% | 43.0% | <0.0001 |

| Medicare | 67.9% | 25.7% | 34.6% | 29.9% | |

| Private | 8.8% | 20.9% | 19.7% | 12.0% | |

| No insurance/self-pay | 7.3% | 19.5% | 17.0% | 14.1% | |

| Unknown / Other | 1.4% | 1.5% | 1.1% | 1.1% | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes | 46.1% | 45.0% | 57.0% | 56.0% | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 31.5% | 37.2% | 40.8% | 27.8% | <0.0001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 29.9% | 30.3% | 36.3% | 33.1% | <0.0001 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 17.9% | 10.6% | 13.3% | 15.1% | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 8.6% | 4.6% | 8.4% | 2.8% | <0.0001 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 5.7% | 4.0% | 3.6% | 3.5% | 0.001 |

| Dementia | 5.3% | 2.0% | 3.6% | 2.1% | <0.0001 |

| Malignancy | 3.4% | 1.7% | 3.4% | 0.7% | <0.0001 |

| Vital Signs/Laboratory Data at Admission | |||||

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 143.5±29.7 | 150.1±30.6 | 145.3±28.8 | 140.5±30.4 | <0.0001 |

| Heart Rate (beats/minute) | 86.6±21.8 | 90.7±19.6 | 87.5±19.5 | 80.5±18.8 | <0.0001 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.6±1.3 | 1.7±1.5 | 1.8±1.6 | 1.9±1.7 | 0.0028 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.9±2.0 | 11.9±2.0 | 11.8±2.0 | 12.0±2.2 | 0.149 |

| Median Household Income (by ZIP) | |||||

| <$20,900 | 0.0% | 2.8% | 5.9% | 0.0% | <0.0001 |

| $20,900–$40,187 | 23.2% | 52.1% | 62.0% | 12.0% | |

| $40,187–$65,501 | 69.8% | 37.5% | 27.2% | 77.5% | |

| $65,501–$105,910 | 6.5% | 7.5% | 4.7% | 10.2% | |

| >$105,910 | 0.5% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.4% | |

| High School Graduate or Greater (% by ZIP) | |||||

| 49%–64% | 3.4% | 15.8% | 38.9% | 5.6% | <0.0001 |

| 64%–74.2% | 12.2% | 17.7% | 27.5% | 25.0% | |

| 74.2%–77.9% | 33.3% | 22.2% | 11.8% | 31.0% | |

| 78%–84.6% | 14.7% | 24.4% | 13.7% | 13.4% | |

| 84.6%–98.3% | 36.6% | 19.9% | 8.1% | 25.0% | |

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

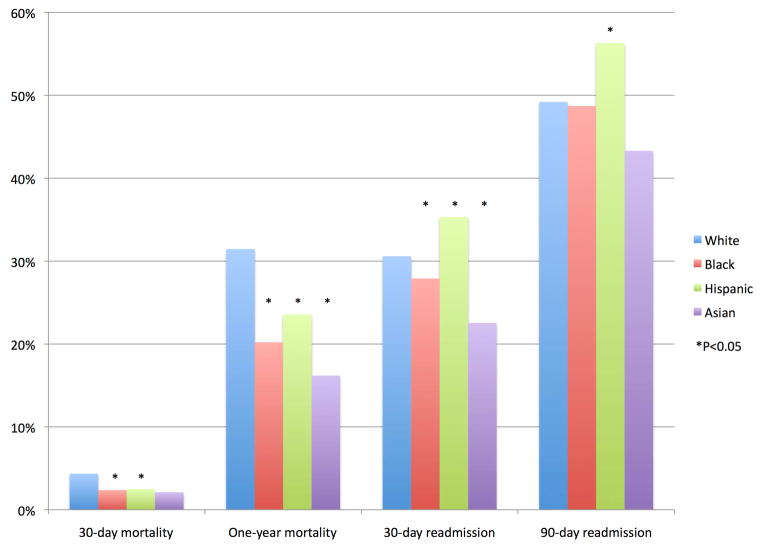

One-year mortality rates were 31% for whites, 20% for blacks, 24% for Hispanics, and 16% for Asians (p<0.0001; Figure 1). After risk adjustment, black and Asian patients had significantly lower odds of one-year mortality than white patients, with adjusted odds ratios of 0.75 (95% CI 0.59–0.94) and 0.57 (95% CI 0.38–0.85), respectively (Table 2). Although Hispanic patients had lower one-year mortality in unadjusted analysis (OR 0.60; 95% CI 0.51–0.72), this difference did not remain statistically significant after risk-adjustment (aOR 0.81; 95% CI 0.64–1.03).

Figure 1. Unadjusted Outcomes After Heart Failure Hospitalization by Race/Ethnicity (N=8,532).

Racial and ethnic differences in unadjusted mortality and readmission rates were present in a municipal health system.

Table 2.

Outcomes after Heart Failure Hospitalization by Race/Ethnicity: Unadjusted and Adjusted GEE Models Compared to White Patients, Odds Ratios (95% CI)

| 30-day mortality | 1-year mortality | 30-day readmission | 90-day readmission | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| White | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Black | 0.53 (0.39–0.73) | 0.81 (0.49–1.33) | 0.49 (0.41–0.57) | 0.75 (0.59–0.94) | 0.80 (0.69–0.93) | 1.04 (0.85–1.28) | 0.87 (0.76–1.00) | 1.22 (1.01–1.47) |

| Hispanic | 0.56 (0.39–0.80) | 0.75 (0.45–1.24) | 0.60 (0.51–0.72) | 0.81 (0.64–1.03) | 1.15 (0.97–1.35) | 1.27 (1.03–1.57) | 1.18 (1.01–1.37) | 1.40 (1.15–1.70) |

| Asian | 0.49 (0.21–1.13) | 0.69 (0.28–1.68) | 0.43 (0.29–0.62) | 0.57 (0.38–0.85) | 0.62 (0.44–0.89) | 0.78 (0.54–1.12) | 0.76 (0.56–1.03) | 1.02 (0.74–1.39) |

Adjusted model includes demographics, utilization/access variables, insurance status, socioeconomic status, clinical variables, comorbid conditions, and admitting hospital.

Thirty-day mortality rates showed similar patterns across racial/ethnic groups: 4.4% for whites, 2.4% for blacks, 2.5% for Hispanics, and 2.1% for Asians. In unadjusted analyses, black and Hispanic patients had lower odds of 30 days mortality compared to white patients with odds ratios of 0.53 (95% CI 0.39–0.73) and 0.56 (95% CI 0.39–0.80), respectively. Given the low number of deaths (6) within 30 days among Asian patients, we found no statistically significant difference in 30 day mortality between Asian and white patients, with an odds ratio of 0.49 (95% CI 0.21–1.13). After risk adjustment, we found no significant differences in 30-day mortality between groups (Table 2).

Thirty-day readmission rates were 31% for whites, 28% for blacks, 35% for Hispanics, and 23% for Asians (Figure 1). Black patients had lower unadjusted odds of 30-day readmission with an odds ratio of 0.80 (95% CI 0.69–0.93), which was not significant after risk adjustment (aOR 1.04; 95% CI 0.85–1.28) (Table 2). Hispanic patients had higher odds of 30-day readmission that did not reach statistical significance in unadjusted analysis (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.97–1.35) but was significant after risk-adjustment (aOR 1.27; 95% CI 1.03–1.57). Asian patients had lower odds of 30-day readmission than white patients (OR 0.62; 95% CI 0.44–0.89), which was no longer statistically significant after risk adjustment (aOR 0.78; 95% CI 0.54–1.12).

Ninety-day readmission rates were 49% for whites, 49% for blacks, 56% for Hispanics, and 43% for Asians (Figure 1). Although rates were similar for white and black patients, black patients had significantly higher risk-adjusted odds of readmission at 90 days compared to white patients with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.21 (95% CI 1.01–1.47). Hispanic patients had significantly higher odds of 90-day readmission (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.01–1.37), which remained after risk-adjustment (aOR 1.40; 95% CI 1.15–1.70). Odds of 90-day readmission for Asian patients were not statistically different from white patients with an unadjusted odds ratio of 0.76 (95% CI 0.56–1.03) and an adjusted odds ratio of 1.02 (95% CI 0.74–1.39).

In our secondary analysis, in which we examined the outcome of days alive out of the hospital in the year following the index hospitalization, results were similar to those for one-year mortality. The mean number of hospital-free days alive for white patients was 274 (95% CI 266–281), for black patients was 303 (95% CI 299–307), for Hispanic patients was 302 (95% CI 297–308), and for Asian patients was 297 (95% CI 282–311). Compared to white patients, the adjusted hazard ratios for black, Hispanic, and Asian patients were 0.65 (95% CI 0.52–0.81), 0.77 (95% CI 0.61–0.96), and 0.67 (95% CI 0.45–0.99), respectively.

Discussion

We found racial and ethnic differences in mortality and readmission after heart failure hospitalization among a predominantly non-white population with a diverse payer mix within a large municipal health system, which persisted after adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical variables. At both thirty days and one year after hospital discharge, white patients had significantly higher unadjusted mortality rates than black, Hispanic, and Asian patients. Risk-adjustment reduced the magnitude of disparities, but did not eliminate them. After risk-adjustment, the odds of one-year mortality were 25% reduced for blacks and almost half for Asians as compared to whites. Conversely, readmissions were significantly higher among Hispanic patients at 30 and 90 days and black patients at 90 days as compared to white patients. In summary, racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes after heart failure hospitalization were present among patients with similar access to a municipal health care system.

Our study is consistent with earlier findings that minority patients have lower mortality rates and higher readmission rates than white patients. Previous studies found similar differences between black and Hispanic patients and white patients, although most of these studies lacked adjustment for socioeconomic, clinical variables, or both, and only two included non-Medicare patients (10–14, 22, 23, 27). Although our study included a relatively small number of Asian American patients, we found lower one-year mortality but no difference in readmissions compared to white patients, consistent with prior data (10, 13, 14). Prior to our study, it remained unknown whether disparities found in administrative or registry data were representative of hospital systems that serve large minority populations with a diverse payer mix. Our study strengthens the evidence for the pattern of lower mortality and higher readmission rates for minorities compared to whites by including a patient population underrepresented in prior studies and adjusting for important clinical and socioeconomic variables.

Pathophysiologic Differences

Many reasons for differences in post-hospitalization outcomes have been proposed. Racial and ethnic differences in the underlying etiology and pathophysiology of heart failure may contribute to differences in outcomes (6, 9, 14, 28–36). Heart failure is commonly associated with diabetes and hypertension in black patients, while white patients have higher rates of coronary disease leading to ischemic cardiomyopathy (9, 28–32, 34, 35). Similarly we found that black, Hispanic, and Asian patients had more hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease compared to white patients. We adjusted for comorbid conditions, blood pressure, and serum creatinine; therefore, while these factors do not fully explain our findings, it is possible that the differences in etiology may affect both mortality and readmissions. Others have suggested that minority patients hospitalized for heart failure may be healthier than whites to explain the discrepancy between lower mortality and higher readmission rates for minority patients (10, 18, 28, 33, 35). Consistent with this hypothesis and prior epidemiologic data, we found that black, Hispanic, and Asian patients were younger than white patients. Based on clinical findings and comorbid conditions, however, our data do not support the hypothesis that minority patients are healthier than white patients at the time of admission.

Access to Ambulatory Care

Heart failure is widely considered an ambulatory-care sensitive condition, and lack of access to ambulatory care may lead to increased hospitalization of minority patients (18, 26, 37, 38). Black patients are more likely than white patients to seek care in emergency departments for heart failure, even when accounting for disease severity, and race, like insurance status, may be related to disposition following ED visit (39, 40). Black patients may seek care in emergency departments due to poorer health literacy, absence of a medical home, and cost-barriers to seeking care, even after controlling for income, education, insurance status, social supports, and comorbid conditions (18, 41). Similarly, Hispanic patients are more likely than white patients to suffer from lack of health insurance access, language barriers, and poor health literacy, which all reduce access to outpatient care and portend worse outcomes (18, 33). Inadequate outpatient access due to waiting lists, financial barriers, or patient perceptions may cause patients to preferentially seek emergency and inpatient care (18, 38). Nonetheless, as a safety net hospital system, HHC is mandated to provide equal access to all patients, which is evidenced by its payer mix (24). Furthermore, we found that minority patients were more likely than white patients to access outpatient care preceding heart failure hospitalization, although most patients of all races did not have prior clinic visits. While the factors underlying lower clinic utilization among white patients could lead to higher mortality, our findings persisted after adjustment for clinic utilization and insurance status. As a result, we believe that access to outpatient care did not eliminate racial and ethnic differences in post-hospitalization outcomes within this municipal health system.

Differences or Disparities

An important question is whether the differences we found represent biologic, genetic, or epigenetic differences that vary across racial/ethnic groups or whether these represent disparities related to underlying inequalities (42). The Institute of Medicine defines racial and ethnic disparities in terms of “differences in the quality of healthcare that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention” (1). While there are pathophysiologic differences of heart failure by race/ethnicity, and we found differences in ambulatory care utilization, these factors do not fully explain the differences in outcomes. Racial and ethnic differences in quality metrics may be explained more by where patients receive care rather than by patient characteristics (43), and disparities in outcomes are greater in hospitals with larger proportions of minority patients (22, 23). Consistent with these findings, our data suggests that disparities are present among patients within a diverse municipal health system. Therefore, we agree with those who have proposed that hospitals with large proportions of minority patients may be an ideal setting to study health disparities and work toward health equity (19, 20, 22, 23, 43).

Promoting Health Equity through Quality Improvement

Although health systems cannot overcome some of the social determinants of health at the root of disparities in heart failure, targeted interventions may reduce disparities (1, 4). Measuring disparities within institutions and engaging hospital leadership may be first steps toward improvement, as many leaders of minority-serving hospitals do not recognize that disparities are present within their organizations (44, 45). Culturally tailored, multidisciplinary interventions that include patients and health systems may reduce disparities (4, 46, 47), but efforts to improve for quality for all can widen disparities if health equity is not an explicit goal (45, 48). Organization-level interventions are more effective at reducing disparities than interventions targeting providers (4). Nurse-led post-discharge care can reduce readmissions and improve quality of life (4). Health information technology has the potential to address several root causes of disparities and improve chronic disease management if tailored to vulnerable populations (49).

Limitations

Studying outcomes stratified by race and ethnicity has inherent limitations, and we did not account for all covariates. First, our study was limited by race and ethnicity collection by hospital report, which may result in misclassification (50). Second, although HHC provides equal access regardless of ability to pay (24), and our data showed more minority patients accessed ambulatory care, it is possible that real or perceived barriers related to primary language or immigration status, for example, may differentially affect access. Third, although all patients were seen within a single health care system, it is possible that there were unmeasured patient or treatment differences between hospitals. Fourth, electronic health records lacked patient-level data on income, education, primary language, and English proficiency, so we used ZIP code level data as a proxy for income and education, which is a validated approach for risk-adjustment in cardiovascular disease (13, 51). Fifth, data regarding ejection fraction was not available in our dataset; as a result, we were not able to risk adjust for this important variable or stratify results by ejection fraction. Sixth, we did not have reliable discharge medication data so were unable to measure important process measures such as compliance with evidence-based therapies following hospitalization. Seventh, we were unable to account for re-hospitalizations outside of New York State or within federal hospitals and deaths outside of New York State. Eighth, our data is from a single health system and may not reflect patterns at other municipal health systems or the broader population. Finally, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons, which may increase the possibility that some of our findings are due to chance.

Conclusions

In conclusion, racial and ethnic disparities in heart failure mortality and readmissions persist within a municipal health system after risk adjustment. Our results suggest that the existence of a municipal health system is not sufficient to eliminate disparities in outcomes. Achieving health equity in heart failure outcomes may require addressing underlying social determinants of health. Nevertheless, institutions that serve large proportions of minority patients may be an ideal place to focus quality improvement efforts to reduce disparities and study interventions to reduce disparities. Improving equity in outcomes for patients with heart failure should remain a priority, and access to a municipal health system is not enough.

Clinical Perspectives.

Racial and ethnic disparities in the outcomes of patients with heart failure are present within a diverse municipal health system after adjusting for covariates. In clinical care of patients with heart failure, it is important to recognize that disparities are present and actively apply strategies to achieve the best possible clinical outcomes for patients. Quality improvement efforts can address health systems challenges that disproportionately impact vulnerable patient populations.

Translational Outlook.

The next step in disparities research is to test specific strategies to address racial and ethnic disparities. Ongoing research is still needed to determine whether quality improvement efforts motivated by shifts toward public reporting and paying for value in health care increase or decrease disparities in outcomes, particularly for vulnerable patient populations. Finally, evidence is needed on how to implement and broadly disseminate interventions that effectively reduce disparities at the hospital and health systems levels.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant KL2 TR000053 and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) grant K08 HS23683. Dr. Ogedegbe is supported by National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute grant K24HL111315.

We thank Yan Rosentsveyg at the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation for his assistance with obtaining the data used in this study.

Abbreviations List

- OR

odds ratio

- aOR

adjusted odds ratios

- HHC

Health and Hospitals Corporation

- SPARCS

New York Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variation

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the authors have relevant relationships with industry or conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser Family Foundation and American College of Cardiology. The weight of the evidence. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2002. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Cardiac Care. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1233–41. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis AM, Vinci LM, Okwuosa TM, Chase AR, Huang ES. Cardiovascular health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5 Suppl):29S–100S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–19. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colvin M, Sweitzer NK, Albert NM, et al. Heart Failure in Non-Caucasians, Women, and Older Adults: A White Paper on Special Populations From the Heart Failure Society of America Guideline Committee. J Card Fail. 2015;21(8):674–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillum RF. Heart failure in the United States 1970–1985. Am Heart J. 1987;113(4):1043–45. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillium RF. Epidemiology of heart failure in the Unite States. Am Heart J. 1993;126(4):1042–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90738-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourassa MG, Gurne O, Bangdiwala SI, et al. Natural history and patterns of current practice in heart failure. The Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(4 Suppl A):14A–9A. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90456-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander M, Grumbach K, Remy L, Rowell R, Massie BM. Congestive heart failure hospitalizations and survival in California: patterns according to race/ethnicity. Am Heart J. 1999;137(5):919–27. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70417-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rathore SS, Foody JM, Wang Y, et al. Race, quality of care, and outcomes of elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2517–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown DW, Haldeman GA, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GH. Racial or ethnic differences in hospitalization for heart failure among elderly adults: Medicare, 1990 to 2000. Am Heart J. 2005;150(3):448–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vivo RP, Krim SR, Liang L, et al. Short- and long-term rehospitalization and mortality for heart failure in 4 racial/ethnic populations. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(5):e001134. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurwitz JH, Magid DJ, Smith DH, et al. Cardiovascular Research Network PRESERVE Study. The complex relationship of race to outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Med. 2015;128(6):591–600. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–2008. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1669–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lillie-Blanton M, Maddox TM, Rushing O, Mensah GA. Disparities in cardiac care: rising to the challenge of Healthy People 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(3):503–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bach PB. Racial disparities and site of care. Ethnic Disparties. 2005;15(2 Suppl 2):S31–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen JJ, Washington EL, Chung K, Bell R. Factors underlying racial disparities in hospital care of congestive heart failure. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(2):206–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. Concentration and quality of hospitals that care for elderly black patients. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(11):1177–82. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. The characteristics and performance of hospitals that care for elderly Hispanic Americans. Health Affairs. 2008;27(2):528–37. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):575–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez F, Joynt KE, Lopez L, Saldana F, Jha AK. Readmission rates for Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure and acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2011;162(2):254–61. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.HHC 2014 Report to the Community. New York City: New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation; 2014. [Accessed July 8, 2015]. http://www.nyc.gov/html/hhc/downloads/pdf/publication/2014-hhc-report-to-the-community.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binanay C, Califf RM, Hasselblad V, et al. Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness: the ESCAPE trial. JAMA. 2005 Oct 5;294(13):1625–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.13.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Neil SS, Lake T, Merrill A, Wilson A, Mann DA, Bartnyska LM. Racial disparities in hospitalizations for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):381–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexander M, Grumbach K, Selby J, Brown AF, Washington E. Hospitalization for congestive heart failure. Explaining racial differences. JAMA. 1995;274(13):1037–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afzal A, Ananthasubramaniam K, Sharma N, et al. Racial differences in patients with heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22(12):791–4. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960221207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaccarino V, Gahbauer E, Kasl SV, Charpentier PA, Acampora D, Krumholz HM. Differences between African Americans and whites in the outcome of heart failure: Evidence for a greater functional decline in African Americans. Am Heart J. 2002;143(6):1058–67. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.122123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Echols MR, Felker GM, Thomas KL, et al. Racial differences in the characteristics of patients admitted for acute decompensated heart failure and their relation to outcomes: results from the OPTIME-CHF trial. J Cardiac Failure. 2006;12(9):684–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamath SA, Drazner MH, Wynne J, Fonarow GC, Yancy CW. Characteristics and outcomes in African American patients with decompensated heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(11):1152–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vivo RP, Krim SR, Cevik C, Witteles RM. Heart failure in Hispanics. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(14):1167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, et al. Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(12):1179–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuyjet AB, Akinboboye O. Acute heart failure in the African American patient. J Card Fail. 2014;20(7):533–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qian FFG, Krim SR, Vivo RP, et al. Characteristics, quality of care, and in-hospital outcomes of Asian-American heart failure patients: Findings from the American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure Program. Int J Cardiol. 2015;15(189):141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Billings J, Zeitel L, Lukomnik J, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on hospital use in New York City. Health Affairs. 1993;12(1):162–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274(4):305–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hugli O, Braun JE, Kim S, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA., Jr United States emergency department visits for acute decompensated heart failure, 1992 to 2001. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(11):1537–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storrow AB, Jenkins CA, Self WH, et al. The burden of acute heart failure on U.S. emergency departments. JACC Heart Fail. 2014 Jun;2(3):269–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaudhry SI, Herrin J, Phillips C, et al. Racial Disparities in Health Literacy and Access to Care Among Patients With Heart Failure. J Cardiac Failure. 2011;17(2):122–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor AL. Racial differences and racial disparities: the distinction matters. Circulation. 2015 Mar 10;131(10):848–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasnain-Wynia R, Kang R, Landrum MB, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities within and between hospitals for inpatient quality of care: an examination of patient-level Hospital Quality Alliance measures. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010 May;21(2):629–48. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jha AK, Epstein AM. Governance Around Quality of Care at Hospitals that Disproportionately Care for Black Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Mar;27(3):297–303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1880-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chien AT, Chin MH, Davis AM, Casalino LP. Pay-for-performance, public reporting, and racial disparities in health care: How are programs being designed? Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 Suppl):283S–304S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trivedi AN, Nsa W, Hausmann LR, et al. Quality and equity of care in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 11;371(24):2298–308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1405003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Aug;27(8):992–1000. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anderson RE, Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, McWilliams JM. Quality of care and racial disparities in medicare among potential ACOs. J Gen Intern Med. 2014 Sep;29(9):1296–304. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2900-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.López L, Green AR, Tan-McGrory A, King R, Betancourt JR. Bridging the digital divide in health care: the role of health information technology in addressing racial and ethnic disparities. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011 Oct;37(10):437–45. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winker MA. Measuring race and ethnicity: why and how? JAMA. 2004;292(13):1612–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas AJ, Eberly EL, Smith GD, Neaton JD, et al. ZIP-code-based versus tract-based income measures as long-term risk-adjusted mortality predictors. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(6):586–90. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]