Abstract

Purpose

Many prostate cancer survivors have lasting symptoms and disease-related concerns for which they seek information. To understand survivors’ information seeking experiences, we examined the topics of their information searches, their overall perceptions of the search, and perceptions of their health information seeking self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in their ability to obtain information). We hypothesized that negative search experiences and lower health information seeking self-efficacy would be associated with certain survivor characteristics such as non-white race, low income, and less education.

Methods

This was a retrospective study using data from the Michigan Prostate Cancer Survivor Study (state-based survey of long-term prostate cancer survivor outcomes, N=2,499, response rate = 38%). Participants recalled their last search for information and reported the topics and overall experience. We conducted multivariable regression to examine the association between survivor characteristics and the information-seeking experience.

Results

Nearly a third (31.7%) of prostate cancer survivors (median age of 76 years and 9 years since diagnosis) reported having negative information seeking experiences when looking for information. However, only 13.4% reported having low health information seeking self-efficacy. Lower income and less education were both significantly associated with negative information seeking experiences.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that many long-term prostate cancer survivors have negative experiences when searching for information, and lower income and less education were survivor factors related to negative information seeking experiences.

Implications for cancer survivors

We advocate for ongoing, information needs assessment at the point-of-care as the survivorship experience progresses to assess and potentially improve survivors’ quality of life.

Keywords: prostate cancer, survivorship, information seeking, information support, quality of life

BACKGROUND

There are approximately three million prostate cancer survivors living in the United States, and this number is projected to grow to four million in 10 years due to favorable survival rates [1]. Along with high survival rates, prostate cancer survivors report a particularly critical need to find a “new normal” due to their lasting physical symptoms. Nonetheless, they are faced with a lack of appropriate support and many have decreased quality of life [2-4]. Additionally, racial and socioeconomic disparities exist: prostate cancer survivors from non-white populations, those with lower income and less education tend to have poorer outcomes and quality-of-life, as well as worse survival rates compared with white, better educated and wealthier counterparts [5-8].

To address follow-up care and improve patient outcomes in this growing population, the American Cancer Society convened a multidisciplinary team of experts to create a list of guidelines for comprehensive prostate cancer survivorship care [9]. These guidelines include a call for primary care clinicians to give appropriate information to help survivors self-manage their symptoms, make decisions, and improve their quality of life many years post-treatment. Having information about one's disease, treatment, and self-management strategies has been shown to improve medical decision-making, communication with one's provider, and psychosocial well-being for all cancer survivors [10-14]. While a sizeable proportion of all cancer survivors actively look for cancer information, survivors have reported experiencing barriers to finding and understanding information, thus, resulting in dissatisfaction and unmet supportive and information needs [15-18].

In a previous study, we reported on long-term prostate cancer survivors’ symptom burden and found that men with greater burden were more likely to need tailored information (e.g., high sexual symptom burden was associated with a greater need for relationship information) [19]. Another previous study from this dataset reported 59.2% of prostate cancer survivors preferred receiving information from their health care providers. Other preferred information sources included: “someone with prostate cancer” (39.4%), “brochures or pamphlets” (37.5%), “National Cancer Institute/American Cancer Society” (36.1%), and “internet” (31.0%) [4]. In the same study, the majority of prostate cancer survivors (82.6%) reported receiving information from their health care providers, their preferred source. Frustration may still exist during information seeking, so in this study, we sought a deeper understanding of long-term prostate cancer survivors’ information seeking experiences to determine if men experienced barriers or struggles during the information gathering process. We also examined the nature of these potential barriers/struggles (e.g., information was too hard to understand). Building on Hesse and colleagues’ previous findings of general information-seeking experiences in all cancer survivors [17], we specifically explored the association between several demographic factors: age, race, marital status, income, education, and health information seeking self-efficacy (defined as one's confidence in obtaining information) and information-seeking experiences in long-term prostate cancer survivors. Based on prior findings, we hypothesized that survivors who were of non-white race, lower income, lower educational attainment, and lower health information seeking self-efficacy would have more negative information seeking experiences.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample Description

This was a retrospective study using data from the Michigan Prostate Cancer Survivor Study, a state-representative follow-back survey of long-term prostate cancer survivor characteristics and outcomes [4]. Individuals diagnosed with prostate cancer in Michigan between 1985 and 2004 and living as of December 31, 2005 were identified from the Michigan Cancer Registry. Stratified random sampling was conducted to ensure adequate inclusion of prostate cancer survivors based on race/ethnicity, residence (urban versus rural), and number of years since diagnosis. African Americans were oversampled due to their higher incidence of prostate cancer and our hypotheses. Exclusion criteria included: unconfirmed cancer, incarceration, unable to be located, non-resident of Michigan, unable to complete the survey, and/or physician recommendation against patient contact. Three rounds of surveys were mailed to the remaining eligible participants (n=6,531) and of those, 2499 surveys were returned (response rate = 38.3%) (See Darwish-Yassine et al, 2014 for more details about data collection).

Measures

Information-seeking experiences (ISEE)

Our primary outcome was a self-reported 4-item measure of Information Seeking Experiences (ISEE) [17, 15]. Respondents recalled their last search for prostate cancer information from any source (e.g., internet, health care provider) and reported agreement to the following items on 4-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree): “It took a lot of effort to get the information you needed”; “You felt frustrated during your search for the information”; “You were concerned about the quality of the information”; “The information you found was too hard to understand.” The items were averaged and examined individually and as a continuous index. Lower scores indicated positive information seeking experiences and higher scores indicated negative information seeking experiences. The ISEE scale has demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.76) [17].

Health Information Seeking Self-Efficacy

Respondents assessed their confidence (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree) in obtaining information with the following single item: “I am confident that I can get advice or information about prostate cancer if I need it.” An average score was calculated for each respondent. Lower scores indicated less health information seeking self-efficacy and higher scores indicated more health information seeking self-efficacy. This item was based on a health information seeking self-efficacy item used in past research [20].

Information sought for long-term prostate cancer survivors

Information sought was assessed via a list of 17 prostate cancer-related topics constructed for this study. Respondents selected all topics of their most recent search for information from the following list: 1. General prostate cancer information; 2. Long-term effects/recovery from cancer; 3. Managing sexual difficulties; 4. Treatment/cures for cancer; 5. Managing urinary problems; 6. Coping with cancer/dealing with cancer; 7. Diagnosis of cancer; 8. Cause of cancer/prevention of cancer; 9. Screening/testing/early detection; 10. General symptoms of cancer; 11. Information on clinical trials; 12. Managing hormone related problems; 13. Paying for medical care/insurance; 14. Alternative/home remedies; 15. Cancer organizations; 16. Where to get medical care; 17. Other (please specify).

Survivor characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics data (age, race, marital status, income, education level, treatment type, time since diagnosis, and recurrence status) were collected through self-report.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe our study population and included the following survivor characteristic variables: age, race, education level, marital status, income, time since diagnosis, treatment type, and recurrence status. We also examined the percentage of survivors reporting specific information searches to determine the top information seeking topics in the sample. Next, we conducted multivariable linear regression analyses to examine survivor characteristics associated with negative information seeking experiences (ISEE separate items and index, health information seeking self-efficacy).

Ethical research approval was granted by the Michigan Public Health Institute (MPHI) and the Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH) Institutional Review Boards, the MPHI privacy officer, and the MDCH Scientific Advisory Panel. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All analyses were conducted using SPSS™ software version 22.

RESULTS

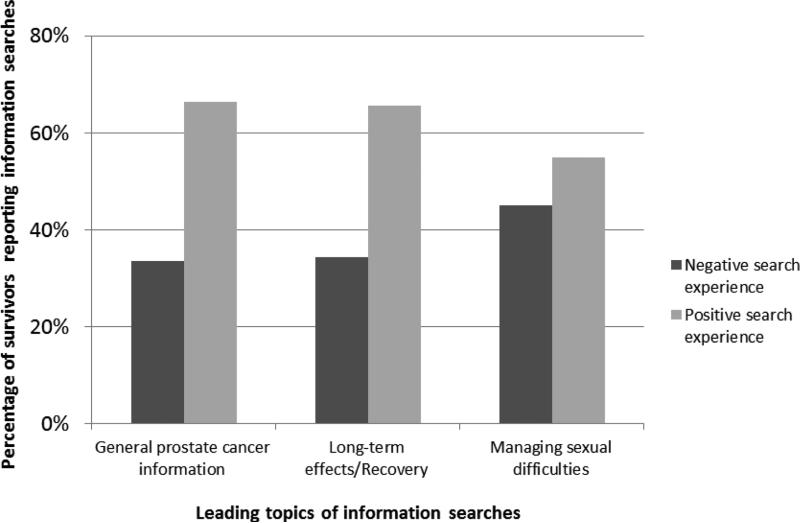

Table 1 reports the survivor characteristics of the sample. Respondents’ median age was 76 years and median time since prostate cancer diagnosis was 9 years. The majority of survivors were married (78%), white (80%), college-educated (40%), 5-9 years since diagnosis (41%), treated with prostatectomy alone (55%), and did not have a recurrence (87.7%). Nearly a third of the entire sample (31.7%) reported having an overall negative information seeking experience when looking for information about prostate cancer. Specifically, 29.2% of the sample had concerns about the quality of information that they obtained and 15.6% of the sample agreed that the information they found was too hard to understand. Approximately a fifth of the sample expressed they felt frustrated during their search for information (18.2%) and that information seeking takes too much effort (20.1%). In addition, 13.4% reported having low health information seeking self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in obtaining information). The top three information topics searched for were general prostate cancer information (47.5%), long-term effects/recovery from cancer (33.9%), and managing sexual difficulties (31.7%). Figure 1 depicts differences in negative/positive information search experiences across the top three most searched topics.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the Michigan Prostate Cancer Survivor Study Population (N=2,499) (from Darwish-Yassine et al. 2014)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Agea | |

| <=64 years | 342 (13.8) |

| 65 – 74 years | 824 (33.3) |

| >=75 years | 1309 (52.9) |

| Raceb | |

| White | 1870 (80.2) |

| Non-white | 461 (19.8) |

| Education level attainedc | |

| Less than high school education | 345 (13.9) |

| High school graduate or GED | 651 (26.3) |

| Some college to college graduate | 989 (40.0) |

| Some graduate school to graduate degree | 489 (19.8) |

| Marital statusd | |

| Not married | 535 (21.6) |

| Married | 1938 (78.4) |

| Incomee | |

| < $20,000 | 316 (13.6) |

| $20,000 – 34,999 | 637 (27.3) |

| $35,000 – 49,999 | 461 (19.8) |

| $50,000 – 74,999 | 418 (17.9) |

| > $75,000 | 498 (21.4) |

| Time since diagnosisf | |

| < 5 years | 266 (11.1) |

| 5 – 9 years | 983 (40.9) |

| 10 – 14 years | 692 (28.8) |

| > 15 years | 465 (19.3) |

| Treatment typeg | |

| Prostatectomy | 1207 (55.1) |

| Combination | 982 (44.9) |

| Recurrence statush | |

| No recurrence | 2119 (87.7) |

| Recurrence | 297 (12.3) |

Note:

Median age = 76 years, missing values=24

missing values=169

missing values=25

missing values=26

missing values=169

Median time since diagnosis = 9 years, missing values=25

missing values=310

missing values=84

Figure 1.

Differences in positive and negative search experiences across the three leading topics of information searches. (N=1460)

We used multivariable linear regression to examine further, the potential associations between survivor characteristics, health information seeking self-efficacy, and the ISEE (separate items and as an index [17]) (Table 2). First, we entered age, race, marital status, income, education level, treatment type, time since diagnosis, recurrence status, and health information seeking self-efficacy into the model of factors associated with ISEE, and the overall model was significant F (9, 1172) = 6.67, p < 0.001, with lower income (β = −0.09, p = 0.008) and lower health information seeking self-efficacy (β = −0.17, p < 0.001) being associated with more negative information seeking experiences. When examining each item separately (too much effort, frustration, concern with information quality, information too hard to understand), income (β = −0.07, p = 0.04; β = −0.09, p = 0.01; β = −0.08, p = 0.02; β = −0.09, p = 0.009, respectively), as well as lower health information self-efficacy (β = −0.19, p < 0.001; β = −0.18, p < 0.001; β = −0.11, p < 0.001; β = −0.13, p < 0.001, respectively) emerged as significant associations in all models. Lower levels of education (β = −0.09, p = 0.01) were also associated with increased feelings that the information obtained was too hard to understand.

Table 2.

Factors associated with information seeking experiences

| Characteristic | ISEE indexa (β, p) | Too much efforta (β, p) | Frustrationa (β, p) | Concern with information qualitya (β, p) | Information too hard to understanda (β, p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.02, 0.60 | 0.04, 0.23 | −0.01, 0.85 | −0.02, 0.59 | 0.03, 0.34 |

| Race | −0.02, 0.48 | −0.03, 0.26 | −0.05, 0.09 | 0.05, 0.07 | −0.05, 0.06 |

| Education level attained | −0.03, 0.33 | −0.01, 0.83 | −0.03, 0.38 | −0.01, 0.83 | −0.09, 0.01** |

| Marital status | 0.01, 0.84 | 0.01, 0.79 | 0.01, 0.78 | 0.004, 0.89 | −0.02, 0.58 |

| Income | −0.09, 0.01** | −0.07, 0.04* | −0.09, 0.01** | −0.08, 0.02* | −0.09, 0.01** |

| Time since diagnosis | −0.01, 0.66 | −0.03, 0.33 | −0.01, 0.80 | −0.03, 0.32 | −0.001, 0.98 |

| Treatment type | 0.01, 0.69 | 0.02, 0.50 | 0.001, 0.98 | 0.02, 0.64 | 0.01, 0.80 |

| Recurrence status | 0.05, 0.11 | 0.03, 0.34 | 0.04, 0.21 | 0.06, 0.06 | 0.06, 0.05 |

| Health information seeking self-efficacy | −0.17, 0.00** | −0.19, 0.00** | −0.18, 0.00** | −0.11, 0.00** | −0.13, 0.00** |

Note:

Lower scores indicate positive information seeking experiences

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

DISCUSSION

In our sample, nearly three-quarters of long-term prostate cancer survivors reported seeking information about prostate cancer in general, and specifically about long-term effects/recovery from cancer and managing their sexual difficulties. Nearly a third of this cohort had negative experiences searching for information even though the majority reported confidence in their ability to seek health information. This suggests that there were significant unmet information needs in this population of prostate cancer survivors.

There is a growing desire among cancer survivors to be active participants in their healthcare, and a 14% increase in cancer information seeking has been documented over the past 10 years [21]. Like Finney Rutten and colleagues’ study, we found that long-term cancer survivors in our sample were actively searching for information; however, we note that still a sizable proportion of our sample (31.7%) reported having negative information seeking experiences, including having concerns about information quality, experiencing frustration during searching, feeling that information seeking takes too much effort, and reporting that information obtained is too hard to understand. Our data suggest that both accessibility and comprehensibility of information are important issues to address in cancer survivorship due to the documented positive association between access to information and improved medical decision-making, communication with one's provider, and psychosocial well-being [10-14].

High health information seeking self-efficacy had a significant association with less negative search experiences as expected. Our results indicate that prostate cancer survivors report negative information seeking experiences, similar to Hesse et al.'s general cancer survivor information-seeking study [17], and provide more supporting evidence that prostate cancer survivors need support managing information environments.

Income and education emerged as being significantly associated with negative information seeking experiences, which partially confirmed our hypothesis. Specifically, having less education was associated with perceptions that the information obtained was too hard to understand. Our findings further support other research indicating that disparities in income and education have negative consequences for prostate cancer survivors’ quality of life [5-8]. Rutten Finney and colleagues report that over the past 10 years, older age, less education, and lower income continue to be factors associated with less information seeking, and the authors conclude that health care providers remain important sources of information in cancer survivor populations [21]. We did not find a significant association between race and information-seeking.

These findings, as well as our prior research [19] suggest that there are unmet information needs in the prostate cancer survivor population, and underscore the fact that prostate cancer survivors continue to have ongoing questions long after their treatment is completed. We found that general prostate cancer information, symptom management, and managing sexual difficulties were all critical topics of interest in this population. Worry about survival and treatment related sexual problems continues to have long-term psychosocial consequences for married prostate cancer survivors and their partners, and these consequences are rarely, if ever effectively addressed in usual prostate cancer survivorship care [3, 22, 23]. The ongoing difficulty prostate cancer survivors have with searching for and obtaining appropriate information suggests that specialty and primary care providers need to both continue to explore unanswered or unaddressed questions with their patients over time, as well as facilitate prostate cancer survivors’ ability to inform their concerns with available resources.

Providers need to have reliable information and resources at the point-of-care to adequately support this population. Hesse and colleagues found the majority of cancer survivors prefer gathering information from their health care providers; however, only a minority actually did [17]. Darwish-Yassine and colleagues found similar supporting evidence: approximately, 60% of their sample listed health care providers as a preferred source of information [4]. Although access to providers’ time may be limited, it is possible that providers can be a gatekeeper or facilitator to direct their patients to high-quality, trusted sources of information. Herein we have compiled a list of suggested resources for primary care providers to provide to prostate cancer survivors (Table 3). These resources may facilitate communication about prostate cancer survivor concerns.

Table 3.

Information resources for long term prostate cancer survivors

| Information Need | Source | Web link |

|---|---|---|

| General prostate cancer information | Men's Cancer Survivor Support, Information and Advocacy, US Too American Cancer Society Movember Foundation |

http://malecare.org/ information about symptoms of advanced prostate cancer, treatments and clinical trials currently enrolling advanced prostate cancer patients http://www.ustoo.org/Home comprehensive website with information about staging, treatments, support groups, clinical trials http://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/detailedguide/prostate-cancer-treating-recurrence information about biochemical relapse and treatment https://us.movember.com/mens-health/prostate-cancer https://cdn.movember.com/uploads/files/2012/PSA_Test_Final.pdf information about risk factors, screening, and treatment, including a decision-making guide for PSA testing. |

| Long-term effects/Recovery from cancer | Michigan Department of Human Services, Michigan Cancer Consortium Men's Cancer Survivor Support, Information and Advocacy Prostate Cancer Foundation |

http://www.prostatecancerdecision.org/HelpAfterTreatment.htm experts’ advice on how to manage 14 symptoms of prostate cancer treatment, including worry about cancer, urinary incontinence and irritability, bowel problems, sexual problems, feelings about sexual problems, hot flashes, fatigue, communication, etc. http://malecare.org/ general symptom management information, including specific issues for gay men http://www.pcf.org/site/c.leJRIROrEpH/b.5822789/k.9652/Side_Effects.htm comprehensive guides to understanding side effects of prostate cancer |

| Managing sexual difficulties | American Cancer Society American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists (AASECT) Society for Sex Therapy and Research (SSTAR) |

http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/002910-pdf.pdf sexuality information for men with cancer http://www.aasect.org includes a locator of certified sex therapists in each US state http://www.sstarnet.org/therapist-directory.php directory of sex therapists in the United States |

Our study has several strengths. First, we used a large cohort of prostate cancer survivors which makes the findings more generalizable. Our sample was limited to Michigan prostate cancer survivors; however, efforts were made to ensure adequate inclusion of prostate cancer survivors based on race/ethnicity, residence (urban versus rural), and number of years since diagnosis; therefore there is no reason to suspect that this state-based sample would stray too far from national estimates. Second, we used a validated brief measure of information seeking experiences, which provided unique insight into the need to not only create relevant supportive information/resources for long-term survivors, but to also develop pathways and practices in usual care through which survivors can access those resources. Third, our study expands prior research suggesting that prostate cancer survivors continue to search for information long term, and have negative experiences during these information searches. Fourth, our study findings are aligned with the current recommendations of the American Cancer Society (ACS) guidelines for prostate cancer survivorship care and add much needed evidence for the necessity of long-term assessment and information support by primary care clinicians at the point of care [9]. Our study also had some limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the survey precludes our ability to generalize results over time, and the retrospective nature of the survey is subject to memory bias. Also, our response rate was 38.3% among eligible participants; however, this is comparable to similar cancer survivorship studies [24]. Despite these limitations, our findings still provide robust evidence that long-term tailored information support is needed for prostate cancer survivors especially in the areas of general prostate cancer information, symptom management, and sexual health.

We have proposed a list of resources that cover three topics we found were important to long-term prostate cancer survivors. Future research can examine the usefulness of these resources in developing information needs assessment interventions at the point-of-care, with a particular aim to address economic and educational disparities. Additionally, the effectiveness of these interventions can be assessed to determine if these approaches improve information seeking experiences and overall quality of life over time.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R25CA117865 to Dr. Bernat and the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award - 2 (CDA 12-171) to Dr. Skolarus. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of interest

Authors Bernat, Skolarus, Hawley, Haggstrom, and Darwish-Yassine declare that they have no conflict of interest. Author Wittmann has Movember Foundation research funding (15-PAF05268) and is a member of the Prostate Cancer Task Force of the Urology Care Foundation, the Educational Committee of the American Urological Association, and the Mental Health committee of the Sexual Medicine Society of America. She has received honoraria for speaking at a community event ($250) and at the American Society for Radiation Oncology ($250).

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):252–71. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. doi:10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burg MA, Adorno G, Lopez ED, Loerzel V, Stein K, Wallace C, et al. Current unmet needs of cancer survivors: Analysis of open-ended responses to the American Cancer Society Study of Cancer Survivors II. Cancer. 2015;121(4):623–30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28951. doi:10.1002/cncr.28951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galbraith ME, Hays L, Tanner T. What men say about surviving prostate cancer: complexities represented in a decade of comments. Clinical journal of oncology nursing. 2012;16(1):65–72. doi: 10.1188/12.CJON.65-72. doi:10.1188/12.cjon.65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darwish-Yassine M, Berenji M, Wing D, Copeland G, Demers RY, Garlinghouse C, et al. Evaluating long-term patient-centered outcomes following prostate cancer treatment: findings from the Michigan Prostate Cancer Survivor study. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice. 2014;8(1):121–30. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0312-8. doi:10.1007/s11764-013-0312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chamie K, Connor SE, Maliski SL, Fink A, Kwan L, Litwin MS. Prostate cancer survivorship: lessons from caring for the uninsured. Urologic oncology. 2012;30(1):102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.09.001. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi Q, Smith TG, Michonski JD, Stein KD, Kaw C, Cleeland CS. Symptom burden in cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: a report from the American Cancer Society's Studies of Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2011;117(12):2779–90. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26146. doi:10.1002/cncr.26146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsey SD, Zeliadt SB, Hall IJ, Ekwueme DU, Penson DF. On the importance of race, socioeconomic status and comorbidity when evaluating quality of life in men with prostate cancer. The Journal of urology. 2007;177(6):1992–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.138. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmid M, Meyer CP, Reznor G, et al. Racial differences in the surgical care of medicare beneficiaries with localized prostate cancer. JAMA Oncology. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3384. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skolarus TA, Wolf AMD, Erb NL, Brooks DD, Rivers BM, Underwood W, et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2014;64(4):225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21234. doi:10.3322/caac.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980-2003). Patient education and counseling. 2005;57(3):250–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.006. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison-Woermke DE, Graydon JE. Perceived informational needs of breast cancer patients receiving radiation therapy after excisional biopsy and axillary node dissection. Cancer nursing. 1993;16(6):449–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michie S, Rosebert C, Heaversedge J, Madden S, Parbhoo S. The effects of different kinds of information on women attending an out-patient breast clinic. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 1996;1(3):285–96. doi:10.1080/13548509608402225. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meredith C, Symonds P, Webster L, Lamont D, Pyper E, Gillis CR, et al. Information needs of cancer patients in west Scotland: cross sectional survey of patients' views. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 1996;313(7059):724–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7059.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derdiarian AK. Effects of information on recently diagnosed cancer patients' and spouses' satisfaction with care. Cancer nursing. 1989;12(5):285–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arora NK, Hesse BW, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, Clayman ML, Croyle RT. Frustrated and confused: the American public rates its cancer-related information-seeking experiences. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):223–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0406-y. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0406-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arora NK, Johnson P, Gustafson DH, McTavish F, Hawkins RP, Pingree S. Barriers to information access, perceived health competence, and psychosocial health outcomes: test of a mediation model in a breast cancer sample. Patient education and counseling. 2002;47(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hesse BW, Arora NK, Burke Beckjord E, Finney Rutten LJ. Information support for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2529–40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23445. doi:10.1002/cncr.23445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McInnes DK, Cleary PD, Stein KD, Ding L, Mehta CC, Ayanian JZ. Perceptions of cancer-related information among cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society's Studies of Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2008;113(6):1471–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23713. doi:10.1002/cncr.23713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernat JK, Wittmann DA, Hawley ST, Hamstra DA, Helfand AM, Haggstrom DA, et al. Symptom burden and information needs in prostate cancer survivors: A case for tailored long-term survivorship care. Under Review at BJU International. 2015 doi: 10.1111/bju.13329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanch-hartigan D, Blake KD, Viswanath K. Cancer Survivors' Use of Numerous Information Sources for Cancer-Related Information: Does More Matter? J Canc Educ. 2014;29(3):488–96. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0642-x. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13187-014-0642-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finney Rutten L, Agunwamba A, Wilson P, Chawla N, Vieux S, Blanch-Hartigan D, et al. Cancer-Related Information Seeking Among Cancer Survivors: Trends Over a Decade (2003–2013). J Canc Educ. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0802-7. doi:10.1007/s13187-015-0802-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavery JF, Clarke VA. Prostate cancer: Patients' and spouses' coping and marital adjustment. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 1999;4(3):289–302. doi:10.1080/135485099106225. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heyman EN, Rosner TT. Prostate cancer: an intimate view from patients and wives. Urologic nursing. 1996;16(2):37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith T, Stein KD, Mehta CC, Kaw C, Kepner JL, Buskirk T, et al. The rationale, design, and implementation of the American Cancer Society's studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2007;109(1):1–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]