Abstract

BACKGROUND

Guideline-based admission therapies for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) significantly improve 30-day survival, but little is known about their association with long-term outcomes.

OBJECTIVES

We evaluated the association of 5 AMI admission therapies (aspirin, beta-blockers, acute reperfusion therapy, door-to-balloon [D2B] time ≤ 90 minutes, and time to fibrinolysis ≤ 30 min) with life expectancy and years of life saved.

METHODS

We analyzed data from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project, a study of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for AMI, with 17 years of follow-up. Life expectancy and years of life saved after AMI were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression with extrapolation using exponential models.

RESULTS

Survival for patients receiving and not receiving the 5 guideline-based therapies diverged early after admission and continued to diverge during 17-year follow-up. Receipt of aspirin, beta-blockers, and acute reperfusion therapy on admission were associated with longer life expectancy of 0.78 (standard error [SE] 0.05), 0.55 (SE 0.06), and 1.03 (SE 0.12) years, respectively. Patients receiving primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 90 minutes lived 1.08 (SE 0.49) years longer than patients with D2B times > 90 minutes, and door-to-needle (D2N) times ≤ 30 minutes were associated with 0.55 (SE 0.12) more years of life. A dose-response relationship was observed between longer D2B and D2N times and shorter life expectancy after AMI.

CONCLUSIONS

Guideline-based therapy for AMI admission is associated with both early and late survival benefits, and results in meaningful gains in life expectancy and large numbers of years of life saved in elderly patients.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, life expectancy, guidelines, survival, elderly

Performance measurement and public reporting are integral to improving care for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (1-3), yet, quantifying the importance of quality measures in real-world populations is challenging. Many AMI guidelines were derived from clinical trials that enrolled younger, healthier patients than the general population with AMI (4-9). Only 4 trials examined long-term survival (5,10-12). The studies focused on short-term outcomes (13-20), and little is known about the long-term magnitude and persistence of these survival benefits.

No prior studies have evaluated the association between the use of AMI guidelines and life expectancy, because to do so requires a large study sample, long-term mortality data, and detailed clinical information. We used data from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project (CCP), which included detailed medical record abstraction and over 17 years of follow-up, to determine the relationship between 5 AMI admission guidelines (aspirin on admission, beta-blockers on admission, acute reperfusion therapy, door-to-balloon [D2B] within 90 minutes, and door-to-needle [D2N] within 30 minutes of arrival) with long-term survival and life expectancy after AMI in elderly patients.

METHODS

DATA SOURCE

The CCP is a national program conducted by the Health Care Financing Administration (now Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) that reviewed medical records from all U.S. Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries hospitalized at acute-care nongovernmental hospitals with a principal discharge diagnosis of AMI (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, code 410) between January 1994 and February 1996 (n = 234,769). AMI readmission code 410.×2 was excluded (21,22). Professional teams at centralized data centers abstracted medical charts for patient demographics, medical history, clinical presentation, and receipt and timing of procedures and medical therapies.

The Yale University institutional review board approved this study.

STUDY SAMPLE

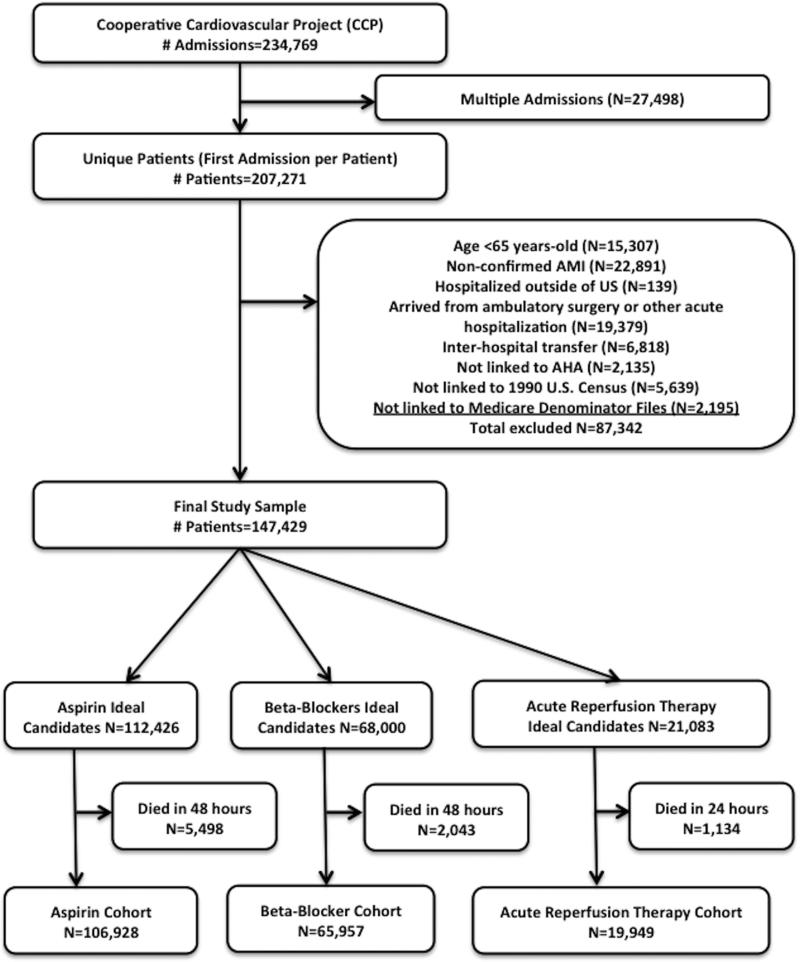

We included all patients ≥ 65 years with a confirmed AMI defined by elevations in cardiac enzymes (creatine kinase-MB or lactate dehydrogenase), chest pain prior to admission, and diagnostic changes on electrocardiography (ST-segment elevation or new pathological Q waves). We excluded patients hospitalized outside of the 50 states, patients who developed AMI during surgery or other acute hospitalizations, and patients who arrived by inter-hospital transfer. We also excluded patients whose records could not be linked to data from the American Hospital Association for hospital characteristics, the 1990 U.S. census information for socioeconomic status, and the Medicare Denominator Files for vital status. Our final study cohort included 147,429 patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of study inclusion criteria.

Separate eligibility criteria were used for each guideline. “Ideal candidates” were defined as being eligible for a particular therapy without specific contraindications per American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines.

In addition to criteria listed above, we used separate eligibility criteria for each guideline. Patients were considered to be “ideal candidates” if they were eligible for a particular therapy and had no therapy-specific contraindications per American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines (Table 1). We excluded ideal candidates for aspirin and beta-blockers who died within 2 days of hospitalization, and ideal candidates for acute reperfusion therapy who died within the first day of hospitalization to ensure that all eligible patients were alive long enough to receive these therapies. For the D2B and D2N guidelines, we required that eligible patients presented within 12 hours of symptom onset with electrocardiographic evidence of ST-elevation AMI or left bundle branch block. Patients had to have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 3 hours or fibrinolytic therapy within 2 hours of presentation.

Table 1.

Definition of Ideal candidates for AMI admission therapies per ACC/AHA guidelines and number of patients excluded for each reason

| Therapy | Eligibility Criteria |

|---|---|

| Aspirin within 48 hours of admission | No bleeding before or at the time of admission (n = 4,433) |

| No history of internal bleeding or a bleeding disorder (n = 782) | |

| No active ulcer disease or gastritis (n = 4,163) | |

| No history of allergy to aspirin (n = 6,408) | |

| No warfarin before admission (n = 10,157) | |

| Did not have anemia (n = 10,485) | |

| Platelet count >100,000 per uL (n =7,928) | |

| Beta-blockers within 48 hours of admission | Heart rate > 50bpm (n = 3,905) |

| No shock before or on admission (n = 3,500) | |

| SBP>100mmHg on admission (n = 11,565) | |

| No second- or third-degree heart block on admission EKG (n = 2,029) | |

| No history of COPD or asthma (n = 30,232) | |

| No history of heart failure (n = 31,966) | |

| No heart failure or pulmonary edema on admission (n = 42,493) | |

| No history of allergy to beta-blockers (n =726) | |

| Acute reperfusion therapy within 24 hours of admission | EKG evidence of ST-segment elevation or LBBB (n = 91,382) |

| Chest pain < 12 hours (n = 56,146) | |

| No bleeding before, or at time of, admission (n = 4,433) | |

| No history of internal bleeding or a bleeding disorder (n = 782) | |

| No chronic liver disease (n = 578) | |

| No surgery in 2 months before admission or trauma in the month before admission (n = 8,265) | |

| Did not experience cardiac arrest with cardiopulmonary resuscitation before admission (n = 5,244) | |

| No history of stroke or CVA, or stroke on admission (n = 21,777) | |

| Not taking warfarin before admission (n = 10,157) | |

| Patient or physician did not refuse thrombolytic therapy or catheterization (n = 16,047) | |

| No hypertensive emergency (n=20,377) | |

| Door-to-balloon time ≤ 90 min | Presented within 12 hours of symptom onset with STEMI or LBBB (n = 110,768) |

| Did not receive fibrinolytic therapy prior to PCI (n = 470) | |

| Received primary PCI within 12 hours of admission (n = 143,908) | |

| Door-to-needle time ≤ 30 min | Presented within 12 hours of symptom onset with STEMI or LBBB (n = 110,768) |

| Did not receive PCI prior to fibrinolytic therapy (n = 101) | |

| Received fibrinolytic therapy on admission (n = 121,094) |

DEFINITIONS OF VARIABLE

We evaluated the association between life expectancy after AMI and 3 guideline-based admission therapies (aspirin within 48 hours of admission, beta-blockers within 48 hours of admission, and acute reperfusion therapy [fibrinolytic agents or PCI] within 12 hours of admission) and 2 reperfusion guidelines (D2B within 90 minutes and D2N within 30 minutes of hospital arrival). We obtained information on receipt and timing of therapies from the medical record data in CCP. To ascertain vital status over 17 years of follow-up, we linked the CCP to the Medicare Denominator files from 1994 to 2012 using Medicare beneficiary health insurance claim (HIC) numbers to obtain dates of death. Because nearly all patients > 65 years of age who qualify for Medicare remain enrolled for life, death information was considered complete for all patients enrolled in CCP.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Baseline characteristics of eligible patients receiving and not receiving each admission guideline therapy were compared separately using chi-squared tests or t-tests. Conditional hazard ratios for the intervals 0 to 30 days, 30 days to 1 year, 1 to 5 years, and 5 to 17 years were calculated using marginal Cox proportional hazards models. This approach accounts for clustering of patients within hospitals and adjusts for hospital site in order to account for differences in the quality of care delivered across hospitals. Only patients alive at the start of the interval were included in the hazard ratio calculations. Models were then repeated adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics.

Covariates were selected using a combination of prior literature and clinical judgment, and included patient demographics, medical history, admission findings, and hospital characteristics. Because patients receiving 1 guideline-based therapy were more likely to receive other therapies, we also adjusted for other admission therapies. Patients with missing data for systolic blood pressure were assigned the cohort's median systolic blood pressure, as well as a binary dummy variable denoting missing data. When covariates were contraindications to receiving a therapy (i.e. CHF for beta-blockers on admission), they were not included in models.

We estimated life expectancy from the time of admission using a 4-step process. First, we limited the sample to eligible patients and fit a marginal Cox proportional hazards model with a dichotomous variable for guideline receipt. Proportional hazards assumptions were checked using Schoenfeld residuals, examined graphically and tested formally. Second, we plotted the 17-year expected survival curves from the Cox models for recipients and non-recipients. Third, we extrapolated the survival curves to age 100 using exponential models. The constant hazard for the exponential model was specified as the average hazard over the last 2 years of follow-up, and the median age of each cohort (i.e. aspirin eligible, beta-blocker eligible) was used to determine the number of years for extrapolation to age 100. We selected exponential models because we lacked information on the shape of the survival curves and thus opted for a model with a constant hazard that does not make assumptions about changes to the hazard function over time. Finally, mean life expectancy estimates were calculated by adding the areas under the proportional hazards and exponential survival functions (Online Figure 1). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95%CI) for the mean were calculated in the same manner using the upper and lower confidence bounds of the expected survival curves. Mean years of life saved by each admission guideline were calculated as the difference in life expectancy between patients receiving and not receiving the guideline. We calculated standard errors from the upper and lower confidence bounds of the survival curves to show uncertainty and significance of estimates. The percentage of life-years saved was defined as the ratio of years of life saved to life expectancy in non-recipients.

To evaluate whether receipt of admission guideline therapy is associated with longer life expectancy after AMI independent of other characteristics, we repeated the life expectancy calculations described above adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics. To plot the adjusted survival curves, we used overall covariate frequencies or means among all eligible patients. By using the same covariate values to plot the survival curves of recipients and non-recipients and thus forcing both groups to have the same risk factor profile, we were able to estimate the adjusted gains in life expectancy associated with each guideline for the “average” eligible patient. Survival curves were again extrapolated to age 100 using exponential models, and life expectancy was calculated by summing the areas under these curves.

We repeated the unadjusted and adjusted life expectancy calculations for aspirin, beta-blockers, and acute reperfusion therapy with age interactions included in the models to determine whether the survival benefits associated with each therapy were consistent across all 5-year age groups. Additionally, we repeated the analyses for aspirin and beta-blockers as 3-level variables (never received, received on admission only, received on admission and discharge) as a sensitivity analysis to determine whether patients receiving these medications on admission only had similar life expectancies as those receiving them on admission and discharge. For these analyses, only patients surviving to discharge were included in the analyses and all survival estimates were calculated from the time of discharge. Similarly, we repeated the D2B and D2N calculations broken down by 30-minute intervals to determine whether patients with greater delays in reperfusion lost more years of life after AMI than those with shorter delays. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the Cox proportional hazards models and life expectancy estimates for intravenous (IV) nitroglycerin, a therapy that is unlikely to have long-term benefits, and compared these estimates to those of aspirin and beta-blockers. Unlike aspirin and beta-blocker therapies, there are no established criteria for identifying ideal candidates for nitroglycerin therapy. Initially, we excluded patients with the following contraindications to nitroglycerin: hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 100mmHg), bradycardia (heart rate < 50bpm, and tachycardia (heart rate > 100bpm) (23). We excluded patients with a history of stroke or anemia because these populations may be at higher risk of adverse outcomes after nitroglycerin therapy due to side effects like methemoglobinemia and increased intracranial pressure (24,25), and pharmaceutical companies and the Food and Drug Administration advise caution when using nitroglycerin formulations in these populations (26,27). Additionally, we excluded patients with heart failure because these patients likely represent a separate subgroup for whom nitroglycerin is commonly prescribed but who also have significantly higher mortality. All analyses were specified a priori and both sets of analyses are included for transparency.

RESULTS

Chart-abstracted sample characteristics for the 147,429 patients eligible for at least 1 guideline-based therapy are presented in Table 2. Of these, 106,928 (72.5%) were eligible for aspirin and 65,957 (44.7%) for beta-blockers (Online Table 1). Patients who received aspirin or beta-blockers were on average younger and more likely to have ST-elevation AMIs and lower Killip class than those who did not. These patients were also more likely to present to hospitals with greater annual AMI volume and more cardiac care capabilities.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics of patients in the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project eligible for at least one measure (N = 147,429)

| Characteristic | N(%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 76.6 ± 7.4 |

| Female sex | 72,529 (49.2) |

| Race | |

| White | 133,599 (90.6) |

| Nonwhite | 13,795 (9.4) |

| Missing | 35 (0) |

| Income, mean ± SD | 30,447 ± 11450 |

| Missing | 3420 (2.3) |

| Medical History | |

| Hypertension | 91.074 (61.8) |

| Diabetes | 45,132 (30.6) |

| Prior CAD | 53,992 (36.6) |

| Prior CHF | 31,966 (21.7) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 20,857 (14.2) |

| COPD | 30044 (20.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 7014 (4.8) |

| Current smoker | 21,582 (14.6) |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2) | 22852 (15.5) |

| Missing | 25996 (17.6) |

| Cancer | 3795 (2.6) |

| Dementia | 9091 (6.2) |

| Anemia | 10485 (7.1) |

| Frailty | |

| Admission from skilled nursing facility | 10156 (6.9) |

| Mobility on admission | |

| Walks independently | 2115327 (78.2) |

| Requires assistance | 28007 (19.0) |

| Missing | 4095 (2.8) |

| Urinary continence on admission | |

| Continent | 132976 (90.2) |

| Incontinent/Anuric | 11026 (7.5) |

| Missing | 3427 (2.3) |

| Clinical Presentation | |

| Killip class | |

| I | 74,239 (50.4) |

| II | 17,786 (12.1) |

| III | 51,904 (35.2) |

| IV | 3500 (2.4) |

| SBP (mmHg), mean ± SD | 115.9 ± 10.9 |

| Missing | 791 (0.5) |

| Heart rate (bpm), mean ± SD | 88.1 ± 24.9 |

| ST-elevation AMI | 42,942 (29.1) |

| Anterior infarction | 68,632 (46.6) |

| Cardiac arrest on admission | 5244 (3.6) |

| Guideline-Based Admission Therapies | |

| Aspirin within 48 hours, of eligible patients | 81,607/106,928 (76.3) |

| Beta-blockers within 48 hours, of eligible patients | 31,818/65,957 (48.2) |

| Acute reperfusion therapy within 12 hours, of eligible patients | 11,225/19,949 (56.3) |

| Door-to-balloon within 90 minutes, of patients receiving primary PCI | 418/1261 (33.2) |

| Door-to-needle within 30 minutes, of patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy | 3088/12,019 (25.7) |

| Hospital Characteristics | |

| AMI volume (per year), mean ± SD | |

| Rural hospital | 31,924 (21.7) |

| Cardiac care facilities | |

| Cardiac surgery suite | 54,101 (36.7) |

| Catheterization only | 37,461 (25.4) |

| No invasive facilities | 44,214 (30.0) |

| Missing | 11,653 (7.9) |

| Ownership | |

| Public | 18,595 (12.6) |

| Not-for-profit | 113,411 (76.9) |

| For-profit | 15,423 (10.5) |

| Teaching status | |

| COTH hospital | 16.709 (11.3) |

| Residency affiliated | 32,345 (21.9) |

| Non-teaching | 98,375 (66.7) |

Abbreviations: AMI = acute myocardial infarction; CAD = coronary artery disease; CHF = congestive heart failure; COTH = Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; SD = standard deviation.

Of the 19,949 patients eligible for acute reperfusion therapy in our sample, 11,225 (56.3%) received either PCI or fibrinolytic therapy (Online Table 2). Patients undergoing reperfusion therapy had fewer comorbidities and lower Killip class than those who did not. A total of 1,261 patients in our sample received primary PCI and 12,019 patients received emergent fibrinolytic therapy. Approximately one-third of patients receiving primary PCI had D2B times ≤ 90 minutes, and 25.7% of patients receiving emergent fibrinolytic therapy had D2N times ≤ 30 minutes.

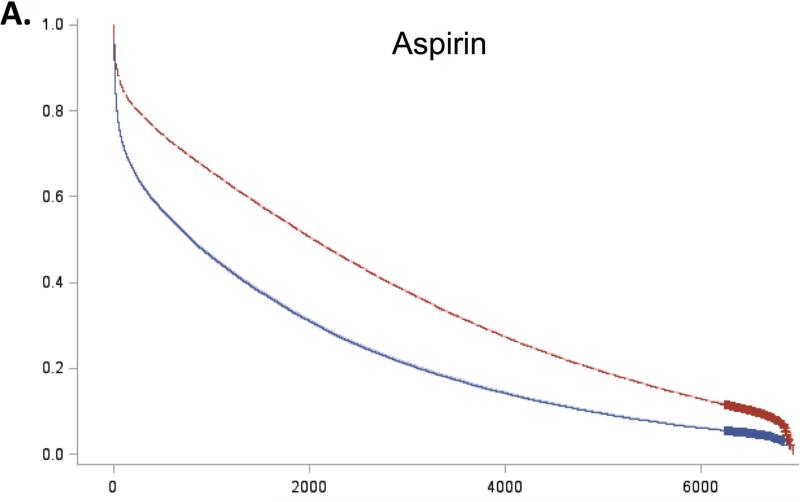

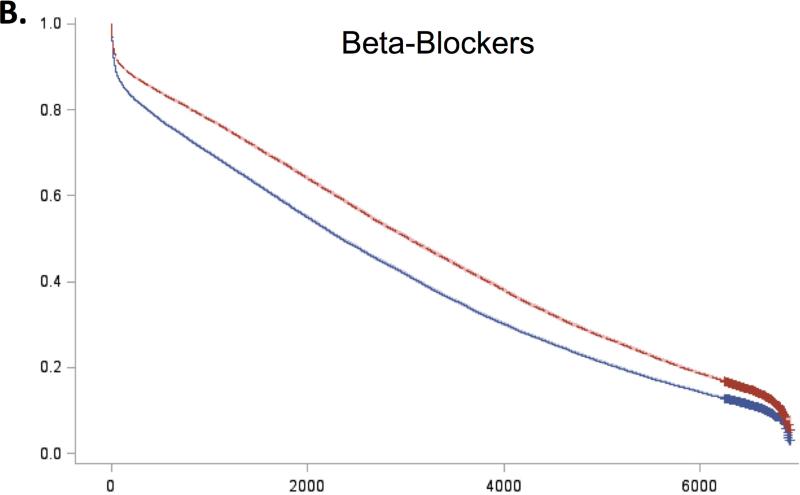

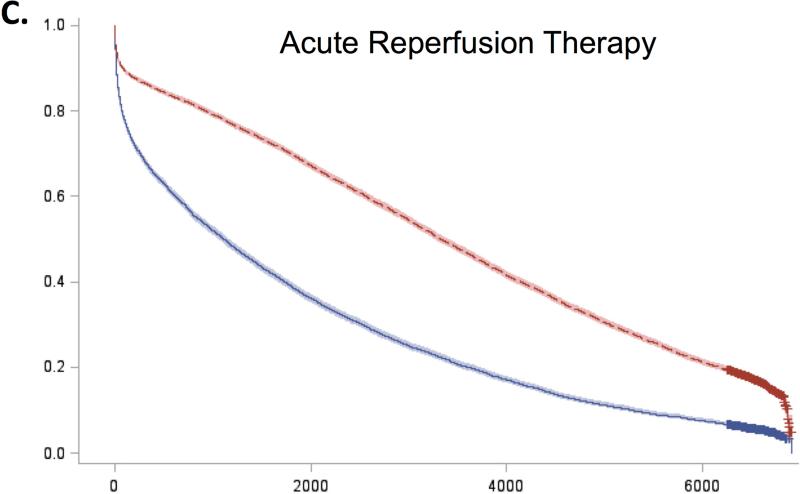

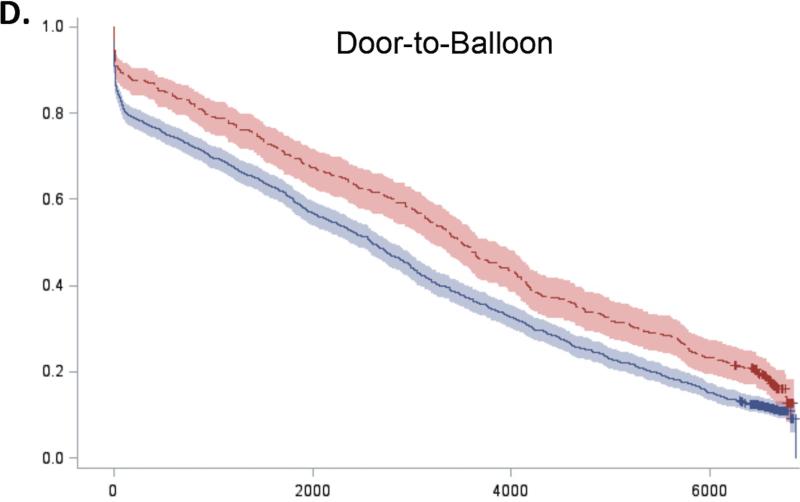

For all 5 guidelines, survival curves of patients receiving and not receiving each therapy separated almost immediately after admission and remained distinct over the duration of follow-up (Figure 2). Patients who received recommended therapies had significantly lower mortality across all follow-up time-points (Online Table 3).

Figure 2. Expected survival curves for those receiving and not receiving A) Aspirin within 48 hours, B) Beta-blockers within 48 hours, C) Acute reperfusion therapy within 12 hours, D) Door to balloon within 90 minutes, and E) Door to needle therapy within 30 minutes, among those eligible for these therapies.

Unadjusted survival curves were calculated using Cox proportional hazards models with only therapy receipt included in the model statement. Survival curves of therapy recipients (red line) and non-recipients (blue line) separated early after admission and remained distinct over the entire duration of follow-up. In all cases, therapy recipients had significantly higher survival than non-recipients.

To further characterize the shape of the survival curves, we repeated the Cox models for 0 to 30 days, 30 days to 1 year, 1 to 5 years, and 5 to 17 years (Table 3). Conditional hazard ratios for aspirin showed divergence of the survival curves up to 5 years of follow-up but no added benefit beyond 5 years (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.96-1.02). In contrast, the survival benefits associated with beta-blockers and acute reperfusion therapy persisted throughout the entire 17 years of follow-up, although the magnitude of this benefit decreased over time (Online Table 4). The survival benefits associated with early reperfusion (D2B ≤ 90 minutes and D2N ≤ 30 minutes) continued to increase up to 1 year after D2B and 5 years after D2N and then persisted up to 17 years after AMI.

Table 3.

Short and Long-term Conditional Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Each Guideline-based Therapy*

| 30-day HR (95% CI) | 30-day to 1-year HR (95% CI) | 1-year to 5-year HR (95% CI) | 5-year to 17-year HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin within 48 hours | 0.73 (0.71, 0.76) | 0.83 (0.80, 0.86) | 0.91 (0.88, 0.94) | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) |

| Beta-blocker within 48 hours | 0.93 (0.88, 0.98) | 0.87 (0.82, 0.91) | 0.90 (0.87, 0.93) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.97) |

| Acute reperfusion therapy | 0.89 (0.80, 0.99) | 0.66 (0.59, 0.73) | 0.75 (0.70, 0.81) | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) |

| D2B time ≤ 90min | 0.80 (0.53, 1.18) | 0.61 (0.36, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.75, 1.35) | 0.84 (0.71, 1.00) |

| D2N time ≤ 30min | 1.02 (0.91, 1.16) | 0.74 (0.62, 0.89) | 0.83 (0.74, 0.93) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.02) |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; D2B = door-to-balloon; D2N = door-to-needle; HR = hazard ratio.

All hazard ratios presented compare the hazards of death in recipients versus non-recipients (reference).

*Models are adjusted for demographics (gender, age, race, ZIP-code level median household income percentile), medical history (hypertension, diabetes, previous coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, current smoking, obesity, cancer, dementia, anemia), frailty measures (admission from a skilled nursing facility, mobility and urinary continence on admission), clinical presentation (Killip class > 2, anterior AMI, pulse and systolic blood pressure on admission, STEMI, cardiac arrest), receipt of other therapies (aspirin, beta-blockers, and acute reperfusion therapy), and hospital characteristics (AMI volume per year, rural location, hospital ownership, and teaching status).

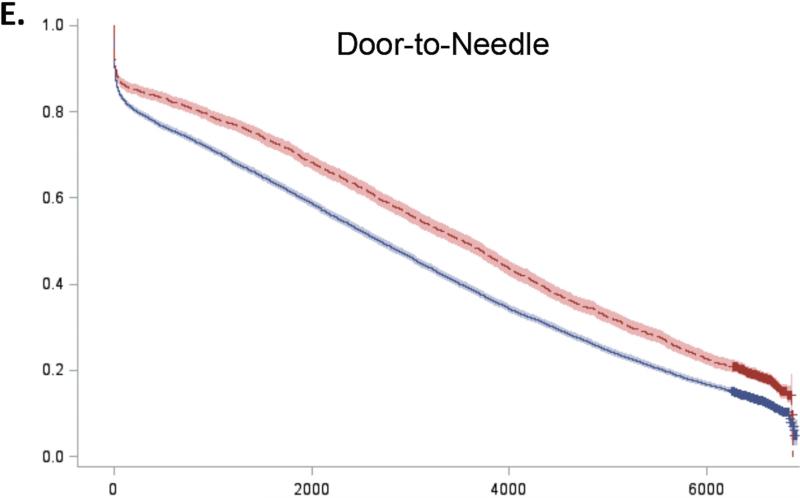

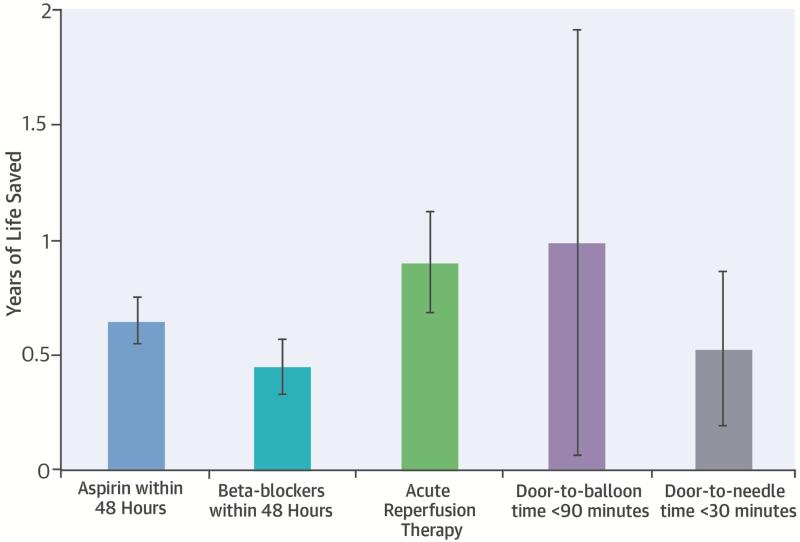

These survival patterns were reflected in the calculated life expectancy estimates (Table 4). For any given therapy, patients receiving the recommended therapies had significantly longer crude life expectancies than those not receiving the measure. Differences in life expectancy persisted after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics although the magnitude of these differences decreased (Table 4). After adjustment, aspirin on admission was associated with 0.65 (standard error [SE] 0.05) years of life saved on average, beta-blockers with 0.45 (SE 0.06) years of life saved, and acute reperfusion therapy with 0.90 (SE 0.11) years of life saved among eligible patients. The absolute number of life-years saved was greater in younger patients for all 3 guidelines; however, the percentage of life-years saved was comparable across age groups (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted life expectancy estimates by receipt of guideline-based therapies

| Recipient LE (years) Mean (95% CI) | Non-recipient LE (years) Mean (95% CI) | Unadjusted Years of Life Saved Mean (SE) | Adjusted* Years of Life Saved Mean (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission Guidelines | ||||

| Aspirin within 48 hours | 7.41 (7.34, 7.48) | 4.69 (4.60, 4.77) | 2.72 (0.06) | 0.65 (0.05) |

| Beta-blocker within 48 hours | 9.43 (9.33, 9.53) | 8.10 (8.00, 8.19) | 1.33 (0.07) | 0.45 (0.06) |

| Acute reperfusion therapy | 10.00 (9.83, 10.17) | 5.48 (5.32, 5.64) | 4.52 (0.12) | 0.90 (0.11) |

| Timing Guidelines | ||||

| D2B time ≤ 90min | 10.31 (0.949, 11.22) | 8.58 (8.00, 9.22) | 1.73 (0.54) | 0.98 (0.47) |

| D2N Time ≤ 30min | 10.44 (10.12, 10.76) | 8.96 (8.76, 9.16) | 1.48 (0.19) | 0.52 (0.17) |

Abbreviations: D2B = door-to-balloon; D2N = door-to-needle; LE = life expectancy; SE = standard error.

Models are adjusted for demographics (gender, age, race, ZIP-code level median household income percentile), medical history (hypertension, diabetes, previous coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, current smoking, obesity, cancer, dementia, anemia), frailty measures (admission from a skilled nursing facility, mobility and urinary continence on admission), clinical presentation (Killip class > 2, anterior AMI, pulse and systolic blood pressure on admission, STEMI, cardiac arrest), receipt of other therapies (aspirin, beta-blockers, and acute reperfusion therapy), and hospital characteristics (AMI volume per year, rural location, hospital ownership, and teaching status).

Figure 3. Age-specific absolute and relative numbers of life-years saved from (A) aspirin, (B) beta-blockers, and (C) acute reperfusion therapy after myocardial infarction.

Numbers of life-years saved were calculated using marginal Cox proportional hazards models with extrapolation using exponential models. Analyses have been adjusted for patient demographics (gender, age, race, ZIP-code level median household income percentile), medical history (hypertension, diabetes, previous coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, current smoking, obesity, cancer, dementia, anemia), frailty measures (admission from a skilled nursing facility, mobility and urinary continence on admission), clinical presentation (Killip class > 2, anterior AMI, pulse and systolic blood pressure on admission, STEMI, cardiac arrest), receipt of other therapies (aspirin, beta-blockers, and acute reperfusion therapy), and hospital characteristics (AMI volume per year, rural location, hospital ownership, and teaching status).

Recipients of aspirin, beta-blockers, and acute reperfusion therapy were significantly more likely to receive additional therapies at discharge. For example, 64% of patients who received aspirin on admission were also prescribed aspirin at discharge, compared with only 33% of non-recipients. Similarly, 63% of patients receiving beta-blockers on admission versus 19% of non-recipients also received beta-blockers at discharge. When aspirin and beta-blocker receipt were examined as 3-level variables in sensitivity analyses, the survival benefit was greatest in patients receiving aspirin or beta-blockers on both admission and discharge (Online Table 5). Compared with patients who did not receive aspirin during hospitalization, receipt of aspirin on admission only was associated with 0.35 (SE 0.05) years of life saved, and receipt of aspirin on admission and discharge was associated with 1.78 (SE 0.05) years of life saved (Online Table 6). There was no difference in life expectancy between patients receiving beta-blockers on admission only and patients not receiving beta-blockers during hospitalization. However, receipt of beta-blockers on both admission and discharge was associated with a significant number of years of life saved (1.01 [SE 0.07] years).

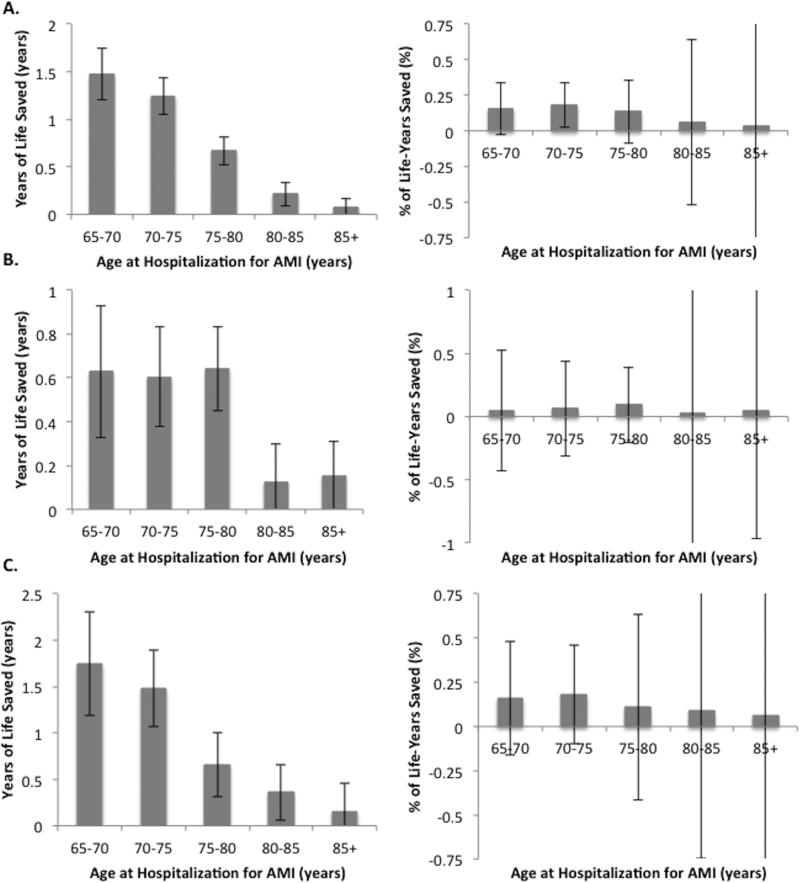

Earlier reperfusion was also associated with significant gains in life expectancy. After adjustment, D2B times ≤ 90 minutes were associated with 0.98 (SE 0.47) years of life saved and D2N times ≤ 30 minutes were associated 0.52 (SE 0.17) years of life saved (Table 4). When D2B and D2N times were further divided into 30-minute intervals, longer times to reperfusion were associated with greater numbers of years of life lost (Figure 4). Compared with patients with D2B times ≤ 90 minutes, patients with times between 121-150 minutes and 151-180 minutes lost 0.95 (SE 0.56) and 1.72 (SE 0.65) years of life, respectively. Similarly, compared with patients with D2N times ≤ 30 minutes, patients with D2N times between 61-90 minutes and 91-120 minutes lost 0.81 (SE 0.21) and 0.71 (SE 0.27) years of life, respectively.

Figure 4. Years of life lost associated with increasing (A) door-to-balloon and (B) door-to-needle time.

Years of life lost by patients with longer door-to-balloon and door-to-needle times are calculated in reference to patients with door-to-balloon times ≤ 90 minutes and door-to-needle times ≤ 30 minutes, respectively. Analyses have been adjusted for patient demographics (gender, age, race, ZIP-code level median household income percentile), medical history (hypertension, diabetes, previous coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, current smoking, obesity, cancer, dementia, anemia), frailty measures (admission from a skilled nursing facility, mobility and urinary continence on admission), clinical presentation (Killip class > 2, anterior AMI, pulse and systolic blood pressure on admission, STEMI, cardiac arrest), receipt of other therapies (aspirin, beta-blockers, and acute reperfusion therapy), and hospital characteristics (AMI volume per year, rural location, hospital ownership, and teaching status).

In sensitivity analyses evaluating survival after IV nitroglycerin (n = 100,907 in patients without contraindications and n = 67,626 in patients without additional exclusions), recipients had significantly lower crude mortality at all follow-up time points than non-recipients (Online Tables 7 and 8). After adjustment, the risk of death was higher in the first 30-days for patients receiving IV nitroglycerin. Among the first group, the long-term risk of death was lower for those receiving IV nitroglycerin at all follow-up times-points (Online Table 9). However, when the additional exclusion criteria were applied, the long-term risk of death was only lower from 1-year to 5-years after AMI. When quantified in terms of life years, receipt of nitroglycerin in this group was not associated with improved long-term mortality. Patients receiving nitroglycerin lived 0.10 (SE 0.06) years longer than those not receiving this therapy (Online Table 10).

DISCUSSION

Our study provides the first estimation of the lifetime benefit of early treatment with guideline-based care for patients hospitalized with AMI. This study indicates that early benefits persist and enlarge over time, resulting in substantial gains in life-years. For every 1000 patients treated with aspirin or beta-blockers on admission, 648 and 450 years of life were saved, respectively. For every 1000 patients treated with fibrinolytic therapy or PCI, 902 years of life were saved; however, these gains differed by timing of receipt. The study provides evidence that intensifies the support for these rapid treatments and estimates what is likely lost by their omission, thereby strengthening the imperative to treat appropriate patients.

Our results extend the findings of previous trials and observational studies by examining AMI admission therapies in the elderly and following patients throughout their lifespan. Several early trials evaluated the prolonged use of aspirin and beta-blockers after AMI and found significant reductions in short-term mortality among patients randomized to these therapies (4-9). We found similar short-term risk reductions in elderly patients with comparable risk ratios to those reported in the trials (Online Table 11). There was a 7% reduction (95% CI 2-12%) in the risk of 30-day mortality and a 10% reduction (95% CI 7-14%) in the risk of 1-year mortality among patients receiving beta-blockers after AMI, which were similar to the 13% for 30-day mortality reported by the MIAMI trial (4) and the 11% for 1-year mortality reported by the ISIS-1 trial (5). The similarities in short-term risk estimates between our data and the trials support our risk adjustment methods and suggest that our models adequately adjusted for differences between therapy recipients and non-recipient.

Our results are consistent with those of prior observational studies in elderly populations. Previous analyses from the CCP reported a 22% decrease in 30-day mortality associated with aspirin administration within 48 hours of admission (14), and a 19% reduction in the odds of inhospital mortality for patients receiving early beta-blocker therapy (19). Similarly, the GRACE study found that, during the index hospitalization, aspirin significantly reduced 6-month mortality for NSTEMI patients and beta-blockers significantly reduced 6-month mortality for both NSTEMI and STEMI patients (18). In addition to admission therapies, lower D2B time has also been associated with lower mortality in-hospital (16,20,28) and at 30-days (17) and 1-year (16). Our study extends these findings to the long term and demonstrates a clear dose-response relationship between longer D2B and D2N times with lower life expectancy.

Of all studies examining the association between AMI admission guidelines and outcomes, only 4 trials have examined mortality beyond the first year. In the first study by von Dornburg et al., the authors investigated the effects of reperfusion therapy (streptokinase with or without coronary angioplasty) on life expectancy in 533 patients with AMI (11). They found that life expectancy was increased by 2.8 years in patients receiving reperfusion therapy compared with those receiving conventional therapy. Similarly, in the ISIS (International Study of Infarct Survival)-1 trial, patients with suspected AMI randomized to atenolol had a 15% decrease in mortality in the first week, which narrowed to 11% at 1 year and became non-significant at 20 months, suggesting beta-blockers were associated with early but not late survival benefits (5). The ISIS-2 trial and the GISSI (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi Nell'Infarto Miocardico)-1 trial demonstrated that the survival curves for patients receiving streptokinase and aspirin separated shortly after admission and then remained parallel over the next 10 years, again suggesting that the survival benefits associated with these therapies were largely limited to the short-term (10,12). In contrast, we found that the survival curves for aspirin, beta-blockers, and acute reperfusion continued to widen over 5 years of follow-up, suggesting that patients receiving these therapies were still accruing a survival advantage well beyond the first year after AMI. Interestingly, there did appear to be a trend towards a long-term effect for patients receiving streptokinase (discharge to 10-year RR 0.84 [95% CI 0.65-1.08]) in the GISSI-I subgroup who were randomized within the first hour, but these analyses may have been underpowered to detect an effect with only 1126 patients.

There are several potential explanations as to why recipients continued to accrue a survival advantage over time. First, early receipt of PCI or fibrinolytic therapy decreases myocardial ischemia and thus can reduce both the size of the infarct and subsequent remodeling (29,30). Preservation of myocardium can improve both regional and global ventricular function, and reduce the rates of heart failure and reinfarction after AMI (31). These persistent benefits may also be seen with early administration of aspirin and beta-blockers. Within minutes of administration, aspirin prevents platelet activation and interferes with platelet adhesion, which may reduce infarct size, progression, or reinfarction (32-35). Similarly, beta-blockade decreases overall myocardial oxygen supply and can minimize myocardial injury (32,36,37). Thus, some of the long-term benefit observed may be due to the immediate effects of aspirin and beta-blockers in reducing the severity and extent of myocardial death. Second, continued use of therapies like aspirin and beta-blockers explains much of the long-term survival advantage observed with these therapies. Recipients of aspirin and beta-blockers were significantly more likely to receive these therapies at discharge and may have been more likely to receive other therapies such as statins, ACE inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers. The 3-level analyses for aspirin and beta-blockers demonstrate that the long-term survival benefits of these therapies were most pronounced in patients receiving these therapies on admission and at discharge. Patients receiving aspirin on admission but not discharge had a smaller but still significant benefit from the early therapy; whereas patients receiving beta-blockers on admission but not discharge showed no differences in long-term survival relative to patients not receiving beta-blockers at all. Interestingly, the only AMI measure to have been retired by CMS is measure AMI-6, which recommended beta-blockers within 24 hours of admission (38). This measure was retired in 2009 due to overwhelming evidence from the COMMIT trial, which showed that early beta blockers after AMI may not be appropriate for certain patient populations (39-41).

Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding by unmeasured confounders, which may explain some of the continued survival benefit if recipients of admission therapies were significantly healthier or at lower risk of adverse outcomes than non-recipients. Although we adjusted for a number of demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics, there are several additional confounders that we were unable to measure, such as receipt of other medications including anti-platelet agents, receipt of aspirin and beta-blockers immediately prior to hospitalization, additional socioeconomic characteristics, and long-term compliance with aspirin and beta-blockers. Nevertheless, the findings of the nitroglycerin sensitivity analyses support the risk adjustment models used in this study. When patients without our set of exclusions were examined, IV nitroglycerin was not associated with an improvement in life expectancy between recipients and non-recipients.

This study strengthens the case for why rapid and early delivery of AMI admission guidelines is important and highlights the magnitude of progress made in improving the quality of care for patients with AMI in the United States. Today, rates of adherence to aspirin and beta-blockers guidelines approach 99%, and 95% of D2B times are < 90 minutes (42). However, when CCP was conducted in the mid-1990s, approximately 25% of patients eligible for aspirin and half of patients eligible for beta-blockers at admission did not receive these therapies. Similarly, two-thirds of patients received PCI after the recommended 90 minutes. Our data imply that if rates of adherence in CCP equaled those today, an additional 15,764 years of life could have been saved by treatment with aspirin, 15,065 years by beta-blockers, and 764 years by shortening D2B times to the recommended 90 minutes. These findings demonstrate the cost of a missed opportunity when eligible patients are not treated.

Although public reporting and pay for performance initiatives have greatly improved the quality of care for AMI patients in the United States, many countries lag behind the United States in implementing these quality measures. Recent reports from Europe, Australia, China, and the Middle East indicate that the percentage of patients with AMI receiving the CMS/Joint Commission admission guidelines varies widely by country. Rates of adherence to aspirin and beta-blocker guidelines range from < 50% in some countries to > 90% in others (13,43-47), but rates of adherence to D2B recommendations have been consistently low across countries (25-60%) (15,48). Thus, opportunities for improving AMI care in other countries are numerous and may result in large gains in both lives saved and years gained.

Our study has its limitations. First, because this is an observational study and not a randomized trial, patients who received the guideline-based therapies likely differ from those who did not. To address this, we limited the analysis to only ideal candidates and then further adjusted for differences in baseline demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics. The IV nitroglycerin sensitivity analyses support the contention that risk adjusted models are sufficient, although patients receiving and not receiving the guideline-recommended therapies may have differed on other unmeasured confounders. Second, the use of guideline-based therapies is strongly associated with the use of other pharmacological interventions. Although we adjusted for other admission guidelines in our analyses, we chose not to adjust for discharge medications because we were interested in the initiation of guideline-based admission therapies rather than one-time doses. We hypothesized that discharge medications may be intermediate variables rather than confounders in the relationship between admission therapies and long-term survival and thus should not adjust for their use. We did evaluate aspirin and beta-blocker receipt as a 3-level variable in sensitivity analyses, which showed that much of the observed benefit was due to both early and late use of aspirin and beta-blockers over the long-term rather than one time use. Third, comparative effectiveness studies are frequently complicated by survivorship bias, whereby patients surviving longer are more likely to receive a particular therapy. We limited analyses to patients who survived the first 24 or 48 hours of hospitalization to ensure that patients lived long enough to receive the admission therapies; however, this requirement may limit the generalizability of our findings to all patients. Finally, the quality of AMI care has improved since data for CCP were collected in the mid-1990s. Compared with older therapies, stents and fibrinolytic agents used today have been shown to increase longevity after AMI. As a result, we may be underestimating the life expectancy gap between guideline recipients and non-recipients.

Although these life expectancy analyses have their limitations, they can only be performed using a dataset such as CCP and will likely never be repeated for several reasons. First, calculation of life expectancy requires complete follow-up over many years, which contemporary datasets currently lack. Second, evaluation of admission therapies requires a sufficient number of patients who did not receive these therapies for comparison. At present, compliance with AMI admission guidelines is > 90% in the vast majority of U.S. hospitals, leaving only small numbers of patients for comparison. Finally, adjustment for differences in patient and hospital characteristics between patients requires an immense dataset with detailed clinical information, such as CCP.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that early survival benefits observed in patients receiving AMI admission guidelines are sustained over the long-term and result in sizeable improvements in life expectancy. Similarly, more rapid time to treatment with direct PCI or fibrinolytic therapy predicted substantial gains in life expectancy for patients undergoing acute reperfusion therapy. These findings illustrate that early and rapid delivery of guideline-based admission therapies for AMI is associated with a large number of not only lives saved early but also years gained over the long term.

Supplementary Material

Central Illustration. Acute MI Admission Therapies and Life Expectancy: Average Number of Life-years Saved.

Prior studies have invariably evaluated improvements in short-term outcomes due to AMI guideline-based therapies. In this study, we quantified life expectancy after AMI and the number of life-years saved by these therapies. Cox proportional hazards regression with extrapolation using exponential models were used to calculate the number of life-years saved attributable to these therapies. All 5 therapies were associated with substantial numbers of life-years saved on average in elderly AMI patients, illustrating the importance of early and rapid delivery of these therapies.

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN PATIENT CARE AND PROCEDURAL SKILLS. In elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), early administration of aspirin, beta-blockers, and reperfusion therapy improves both short-term survival and years of life preserved.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK. Although substantial progress has been made in providing guideline-directed care for patients with AMI in the United States, more work is needed to extend similar gains throughout the world.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Bucholz had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The author acknowledges the assistance of Qualidigm and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in providing data, which made this research possible. The content of this publication does not reflect the views of Qualidigm or CMS, nor does mention of organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented.

Funding Sources: Dr. Bucholz is supported by an F30 Training grant F30HL120498-01A1 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by NIGMS Medical Scientist Training Program grant T32GM07205. Dr. Krumholz is supported by grant U01 HL105270-04 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Drs. Butala, Normand, and Wang report no financial disclosures that contributed to the production of this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- CCP

Cooperative Cardiovascular Project

- CI

confidence interval

- D2B

door-to-balloon

- D2N

door-to-needle

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- SE

Standard error

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Dr. Krumholz has received research grants from Medtronic, Inc (Minneapolis, MN) and Johnson and Johnson (New Brunswick, NJ) through Yale University for the purpose of disseminating clinical trials and chairs the Cardiac Scientific Advisory Board for United Health (Minneapolis, MN). Dr. Normand is a member of the Board of Directors of Frontier Science and Technology (Boston, MA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Oakbrook IL. Core Measure Sets. The Joint Commission; 2014. [March 12, 2014]. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/core_measure_sets.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krumholz HM, Anderson JL, Brooks NH, et al. ACC/AHA clinical performance measures for adults with ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. Circulation. 2006;113:732–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.172860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Process of Care Measures. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS); Baltimore, M.D.: 2013. [March 12, 2014]. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalProcessOfCareMeasures.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metoprolol in acute myocardial infarction (MIAMI) A randomised placebo-controlled international trial. The MIAMI Trial Research Group. Eur Heart J. 1985;6:199–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Randomised trial of intravenous atenolol among 16,027 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-1. First International Study of Infarct Survival Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1986;2:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1988;2:349–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dargie HJ. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1385–90. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein S. Propranolol therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the Beta-Blocker Heart Attack Trial. Circulation. 1983;67:I53–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedersen TR. The Norwegian multicenter study of Timolol after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1983;67:I49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baigent C, Collins R, Appleby P, Parish S, Sleight P, Peto R. ISIS-2: 10 year survival among patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction in randomised comparison of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither. The ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. BMJ. 1998;316:1337–43. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Domburg RT, Sonnenschein K, Rieuwlaat R, et al. Sustained benefit 20 years after reperfusion therapy in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franzosi MG, Santoro E, De Vita C, Geraci E, Lotto A, Maggioni AP, et al. Ten-year follow-up of the first megatrial testing thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction: results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto-1 study. Circulation. 1998;98:2659–65. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.24.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jernberg T, Johanson P, Held C, Svenblad B, Lindback J, Wallentin L. Association between adoption of evidence-based treatment and survival for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2011;305:1677–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krumholz HM, Radford MJ, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Aspirin in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction in elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Patterns of use and outcomes. Circulation. 1995;92:2841–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longenecker JC, Alfaddagh A, Zubaid M, et al. Adherence to ACC/AHA performance measures for myocardial infarction in six Middle-Eastern countries: association with in-hospital mortality and clinical characteristics. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1406–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Nallamothu BK, et al. Association of door-to-balloon time and mortality in patients > or = 65 years with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger PB, Ellis SG, Holmes DR, Jr., et al. Relationship between delay in performing direct coronary angioplasty and early clinical outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the global use of strategies to open occluded arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes (GUSTO-IIb) trial. Circulation. 1999;100:14–20. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg RJ, Currie K, White K, et al. Six-month outcomes in a multinational registry of patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome (the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events [GRACE]). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:288–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krumholz HM, Radford MJ, Wang Y, Chen J, Marciniak TA. Early beta-blocker therapy for acute myocardial infarction in elderly patients. Ann Int Med. 1999;131:648–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-9-199911020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNamara RL, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al. Effect of door-to-balloon time on mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2180–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marciniak TA, Ellerbeck EF, Radford MJ, et al. Improving the quality of care for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. JAMA. 1998;279:1351–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramunno LD, Dodds TA, Traven ND. Cooperative Cardiovascular Project (CCP) quality improvement in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. O/ 1998;21:442–60. doi: 10.1177/016327879802100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, Diercks D, Egan J, Ghaemmaghami C, et al. 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science. Circulation. 2010;122:S787–817. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aiyagari V, Gorelick PB. Management of blood pressure for acute and recurent stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:2251–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saxon SE, Silverman ME. Effects of continuous infusion of intravenous nitroglycerin on methemoglobin levels. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56:461–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90886-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nitrolingual pumpspray (nitroglycerin) spray. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; [February 28, 2016]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm433470.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nitrostat. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; [February 28, 2016]. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/021134s007lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lambrew CT, et al. Relationship of symptom-onset-to-balloon time and door-to-balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283:2941–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.22.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Touchstone DA, Beller GA, Nygaard TW, Tedesco C, Kaul S. Effects of successful intravenous reperfusion therapy on regional myocardial function and geometry in humans: a topographic assessment using two-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:1506–13. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marino P, Zanolla L, Zardini P. Effect of streptokinase on left ventricular modeling and function after mycoardial infarction: the GISSI (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi Nell'Infarto Miocardico) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:1149–58. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90409-9. (GISSI) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goel K, Pinto DS, Gibson CM. Association of time to reperfusion with left ventricular function and heart failure in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review. Am Heart J. 2013;165:451–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verheugt FW, van der Laarse A, Funke-Kupper AJ, Sterkman LG, Galema TW, Roos JP. Effects of early intervention with low-dose aspirin (100mg) on infarct size, reinfarction and mortality in anterior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:267–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90833-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freimark D, Matetzky S, Leor J, et al. Timing of aspirin administration as a determinant of survival of patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolysis. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:381–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02256-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdelnoor M, Landmark K. Infarct size is reduced and the frequency of non-Q-wave myocardial infarctions is increased in patients using aspirin at the onset of symptoms. Cardiology. 1999;91:119–26. doi: 10.1159/000006891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hjalmarson A, Herlitz J, Holmberg S, Ryden L, Swedberg K, Vedin A, et al. The Goteborg metoprolol trial. Effects on mortality and morbidity in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1983;67:I26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, collins R, Sleight P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;27:335–71. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(85)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Office of Clinical Standards and Quality . CMS updates the National Hospital Quality Measure Acute Myocardial Infarction Set for Discharges as of April 1, 2009 [Memorandum] Department of Health and Human Services; Baltimore, MD: [February 8, 2016]. (at https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/hospitalqualityinits/downloads/hospitalami-6factsheet.pdf.) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chatterjee S, Chaudhuri D, Vedanthan R, et al. Early intravenous beta-blockers in patients with acute coronary syndrome – a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:915–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brandler E, Paladino L, Sinert R. Does the early administration of beta-blockers improve the in-hospital mortality rate of patients admitted with acute coronary syndrome? Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez MI, Musini VM, Wright JM. Effect of early treatment with anti-hypertensive drugs on short and long-term mortality in patients with an acute cardiovascular event. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Oct 7;(4):CD006743. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006743.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hospital Compare. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS); Baltimore, M.D.: 2014. [July 5, 2014]. Available at: http://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuch B, Wende R, Barac M, et al. Prognosis and outcomes of elderly (75-84 years) patients with acute myocardial infarction 1-2 years after the event: AMI-elderly study of the MONICA/KORA Myocardial Infarction Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2011;149:205–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J, Li X, Wang Q, et al. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in China from 2001 to 2011 (the China PEACE-Retrospective Acute Myocardial Infarction Study): a retrospective analysis fo hospital data. Lancet. 2015;385:441–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60921-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luthi JC, McClellan WM, Flanders WD, Pitts SR, Burnand B. Variations in the quality of care of patients with acute myocardial infarction among Swiss university hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:229–34. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schiele F, Meneveau N, Seronde MF, et al. Changes in management of elderly patients with myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:987–94. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vermeer NS, Bajorek BV. Utilization of evidence-based therapy for the secondary prevention of acute coronary syndromes in Australian practice. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33:591–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flotta D, Rizza P, Cascarelli P, Pileggi C, Nobile CG, Pavia M. Appraising hospital performance by using the JCAHO/CMS quality measures in Southern Italy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.