Abstract

Background

Gene duplication is prevalent in many species and can result in coding and regulatory divergence. Gene duplications can be classified as whole genome duplication (WGD), tandem and inserted (non-syntenic). In maize, WGD resulted in the subgenomes maize1 and maize2, of which maize1 is considered the dominant subgenome. However, the landscape of co-expression network divergence of duplicate genes in maize is still largely uncharacterized.

Results

To address the consequence of gene duplication on co-expression network divergence, we developed a gene co-expression network from RNA-seq data derived from 64 different tissues/stages of the maize reference inbred-B73. WGD, tandem and inserted gene duplications exhibited distinct regulatory divergence. Inserted duplicate genes were more likely to be singletons in the co-expression networks, while WGD duplicate genes were likely to be co-expressed with other genes. Tandem duplicate genes were enriched in the co-expression pattern where co-expressed genes were nearly identical for the duplicates in the network. Older gene duplications exhibit more extensive co-expression variation than younger duplications. Overall, non-syntenic genes primarily from inserted duplications show more co-expression divergence. Also, such enlarged co-expression divergence is significantly related to duplication age. Moreover, subgenome dominance was not observed in the co-expression networks – maize1 and maize2 exhibit similar levels of intra subgenome correlations. Intriguingly, the level of inter subgenome co-expression was similar to the level of intra subgenome correlations, and genes from specific subgenomes were not likely to be the enriched in co-expression network modules and the hub genes were not predominantly from any specific subgenomes in maize.

Conclusions

Our work provides a comprehensive analysis of maize co-expression network divergence for three different types of gene duplications and identifies potential relationships between duplication types, duplication ages and co-expression consequences.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-016-3194-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Gene duplication, Gene expression, Co-expression network, Regulatory divergence, Maize (Zea mays L.)

Background

Gene duplication exists widely in nature, and can be divided into whole genome duplication, local (tandem) duplication, single gene transposition-duplication and chromosomal duplication [1]. Nearly all higher plants have experienced at least one whole genome duplication (WGD) and tandem/segmental duplications are also widely observed [2–4]. Gene duplication plays a vital role in evolution [5], and has been suggested to be more important than point mutations [6]. In vertebrates, large- and small-scale gene duplications contributed predominantly to the evolution and adaptive radiation of species [7]. Moreover, gene duplication followed by the diversity of genomic content and gene regulation is probably the major factor resulting in the speciation and adaptation in plants [8]. The additional copies of genes can introduce functional redundancy, which may promote evolutionary processes at either the coding or the regulatory level [9]. Duplicate copies may be affected by nonfunctionalization, where pseudogenization occurs, or neofunctionalization, where a novel gene function emerges, or subfunctionalization, where duplicate genes partition and share the ancestral gene function in different tissues and/or developmental stages [1, 6, 9–12].

Transcript abundance variation among duplicate genes is well-documented [13]. Gene duplication can increase gene expression diversity within and between species [14]. Duplicate genes can enable specialized expression differences in different tissues or developmental stages, as well as under different biotic or abiotic stress conditions [15–25]. Moreover, WGD was associated with co-expression regulatory network partitioning in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, resulting in more complex regulatory diversity [26]. In allohexaploid bread wheat, Pfeifer and colleagues explored the transcriptome dynamics and identified cell type- and stage-dependent genome dominance, indicative of genome interplay among different cell types in a polyploid cereal genome [27]. Thus, following duplication, there is a trend toward increased complexity and specialization among duplicate pairs and other interacting genes.

Maize provides a useful system to study the regulatory divergence of duplicate genes. Maize has undergone a recent WGD event ~5–12 Mya followed by whole genome rearrangement, which combined the duplicated chromosomes into a diploid genome containing 10 mosaic chromosomes [28]. The maize genome is divided into two distinct subgenomes, referred to as maize1 and maize2 [29]. Based on greater gene retention and higher expression level among homeologs, maize1 exhibits subgenome dominance over maize2 [29]. Widespread neofunctionalization was also observed between homeologs in maize1 and maize2 assuming that both ancient genomes were equal at the moment of WGD [30]. Purifying selection and dominant gene expression contributed to subgenome evolution after the recent WGD in maize [31]. In addition to the expression divergence permitted by WGD in maize, segmental gene duplication (i.e. tandem duplication and inserted duplication) was also shown to be related with the differential expression of maize genes with different tissue expression specificities [32–35]. However, the landscape of whole-genome regulatory divergence of maize WGD, inserted and tandem duplication events remains largely unexplored.

Co-expression network approaches provide insights into the patterns of transcriptome organization and suggest common biological functions for networked genes. Co-expression edges represent significant expression level correlations between genes based on expression profiles across a set of samples. Clusters of genes with co-expression edges are grouped into shared modules in the co-expression network. A number of studies have utilized diverse datasets (microarray data and RNA-seq data) to identify modules of genes with shared patterns of expression in plants [36–40]. There is also evidence that co-expression modules can be conserved across species [41, 36, 42]. In some cases, genes exhibiting coordinated expression across samples are biologically co-regulated [43]. Thus, co-expression modules have the potential to infer the regulatory network of genes. The availability of a maize genome sequence [44] and ample transcriptome datasets [45] provides an opportunity to explore the regulatory (co-expression) outcomes of duplicate genes. Of particular interest is the co-expression divergence of duplicated genes in maize 1 and maize 2 subgenomes. The functional divergence of duplicate genes, especially the subgenome interplay and divergence at the co-expression network level, was specifically addressed in this work.

Here, we developed a gene co-expression network from a transcriptome dataset consisting of 64 different tissues and stages from the reference inbred – B73. A total of 189 co-expression modules with at least ten genes were identified. We uncovered significant differentiation in co-expression networks among WGD, inserted and tandem duplications. Although the maize1 subgenome exhibits dominance in terms of gene retention and expression level, there is no significant bias of intra subgenome correlations within either of the two subgenomes. Our study provides a genome-wide classification of co-expression network divergence for different types of duplicate genes and uncovers similar levels of inter and intra subgenome interactions after WGD in maize.

Results and discussion

Development of a maize co-expression network

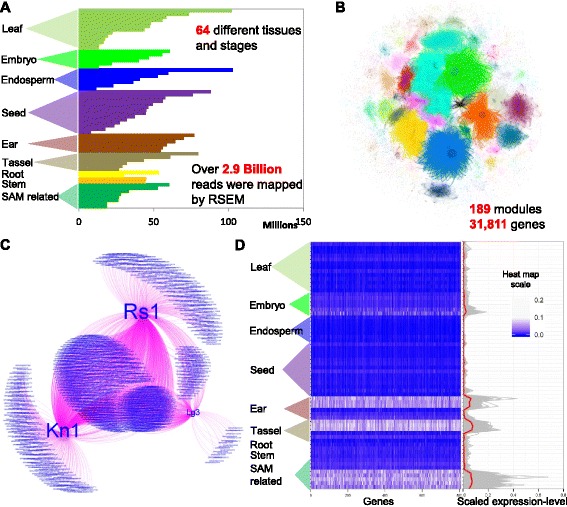

To explore the potential regulatory divergence of duplicate genes in maize, we utilized a RNA-Seq dataset (Fig. 1a and Table 1) from 64 different tissues and developmental stages of the reference inbred B73. These tissues and stages were classified into several distinct plant structures shown in Fig. 1a. More than 3.5 billion NGS reads were obtained and mapped to the maize B73 reference genome version 3 [44]. Over 2.9 billion reads were mapped to profile the transcriptome variation across different tissues and stages in maize (Table 1). Co-expression of genes was determined (see Methods for details) and several Z score thresholds were tested based on the biological means and statistical stringency (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Significant co-expression relationships (Z score >2.5) were adopted to construct a co-expression network, which contained 189 moderate-size modules of 31,811 genes (Fig. 1b). This network was integrated into the COB database [40] and can be explored by selecting the SAM dataset [46].

Fig. 1.

A co-expression network constructed in maize. a The distribution of uniquely-mapped reads in each tissue/stage. Detailed information on each tissue and developmental stage is available in Table 1. b A gene co-expression network for maize, including 189 modules with 31,811 genes. The co-expression network can be explored at the online database [46]. The blue module in the co-expression network shows a shoot apical meristerm specific sub-network. c A shoot apical meristem (SAM) module involving well-known SAM-expressed genes. Each node represents one gene, while each edge (line) linking two nodes indicates a significant co-expression correlation. Kn1, Rs1 and Lg3 represent the Knotted1, Rough Sheath1 and Liguleless3 genes, respectively. The size of gene labels is in accordance with the node size, which is further determined by the number of co-expressed genes. d The tissue-specific expression pattern of the SAM-specific module shown in C. Each row of the heatmap (left panel) indicates one tissue/stage and each column represents one gene. Each line of the plot (right panel) represents one gene; the red line shows the average scaled expression level across all tissues/stages

Table 1.

Transcriptome Datasets used in our study

| ID | Tissues/Stages | Tissue classification | # Total reads | % contaminating adaptor sequences | % bases >q20 | Uniquely mapped reads in FGS gene space | % reads in FGS gene space | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Trans | SAM related - embryo | 22994564 | 5.24 | 95.87 | 17664753 | 76.82 | [63] |

| 2 | LM | SAM related - LM | 33567585 | 3.66 | 97.70 | 18748653 | 55.85 | [63] |

| 3 | L1 | SAM related - embryo | 39027020 | 2.11 | 98.14 | 25877026 | 66.31 | [63] |

| 4 | L14 | SAM related - embryo | 31676873 | 3.31 | 98.10 | 24636049 | 77.77 | [63] |

| 5 | Col | SAM related - embryo | 41066790 | 2.95 | 98.05 | 27532949 | 67.04 | [63] |

| 6 | V5_Shoot_tip | SAM containing | 37966015 | 5.49 | 96.71 | 31957110 | 84.17 | [45] |

| 7 | V3_Stem and SAM | SAM containing | 75700900 | 7.24 | 90.86 | 58077428 | 76.72 | [45] |

| 8 | V1_4D_PE_Stem_SAM | SAM containing | 68096357 | 5.66 | 95.80 | 58736028 | 86.25 | [45] |

| 9 | V5_First_elonagetd_internode | stem | 50620425 | 5.42 | 96.78 | 42021210 | 83.01 | [45] |

| 10 | V9_Fourth_elongated_internode | stem | 49883803 | 4.68 | 96.64 | 42811552 | 85.82 | [45] |

| 11 | V1_4D_PE_Primary_root | root | 34338211 | 5.38 | 96.03 | 28431679 | 82.80 | [45] |

| 12 | 6DAS_GH_Primary Root | root | 75974682 | 7.89 | 94.81 | 58789326 | 77.38 | [45] |

| 13 | tassel_stg1 | tassel | 41685877 | 1.38 | 99.38 | 37715842 | 90.48 | [64] |

| 14 | tassel_stg3 | tassel | 44907570 | 1.60 | 99.08 | 39810029 | 88.65 | [64] |

| 15 | tassel_stg2 | tassel | 33527176 | 1.28 | 98.97 | 29884294 | 89.13 | [64] |

| 16 | R1_Anthers | tassel | 50390993 | 6.51 | 95.22 | 42255501 | 83.86 | [45] |

| 17 | V13_Immature_tassel | tassel | 67777936 | 4.83 | 96.86 | 57328334 | 84.58 | [45] |

| 18 | V18_Meiotic_tassel | tassel | 90322080 | 4.17 | 96.99 | 76409461 | 84.60 | [45] |

| 19 | V18_Immature_cob | ear | 63065877 | 4.27 | 96.92 | 51946957 | 82.37 | [45] |

| 20 | ear_tip | ear | 19469355 | 3.85 | 97.91 | 17259171 | 88.65 | [64] |

| 21 | ear_mid | ear | 22832854 | 1.66 | 98.69 | 20181747 | 88.39 | [64] |

| 22 | ear_base | ear | 22257472 | 2.06 | 99.34 | 19599692 | 88.06 | [64] |

| 23 | R1_Pre-pollination_cob | ear | 78890387 | 3.61 | 97.56 | 65827854 | 83.44 | [45] |

| 24 | R1_Silks | ear | 85297444 | 3.47 | 97.73 | 73722387 | 86.43 | [45] |

| 25 | 16DAP_Whole_seed | seed | 36090184 | 5.88 | 96.18 | 30262739 | 83.85 | [45] |

| 26 | 24H_Germinating Seed | seed | 67115301 | 9.53 | 93.24 | 50590975 | 75.38 | [45] |

| 27 | 14DAP_Whole_seed | seed | 57197138 | 8.00 | 94.15 | 49994899 | 87.41 | [45] |

| 28 | 10DAP_Whole_seed | seed | 59980127 | 6.77 | 95.05 | 51983114 | 86.67 | [45] |

| 29 | 12DAP_Whole_seed | seed | 55057984 | 7.51 | 94.26 | 47658798 | 86.56 | [45] |

| 30 | 18DAP_Pericarp | seed | 45315693 | 8.06 | 94.50 | 37642629 | 83.07 | [45] |

| 31 | 2DAP_Whole_seed | seed | 50626444 | 7.31 | 94.38 | 43151312 | 85.23 | [45] |

| 32 | 18DAP_Whole_Seed | seed | 54296830 | 9.77 | 92.49 | 47308022 | 87.13 | [45] |

| 33 | 6DAP_Whole_seed | seed | 53677071 | 10.33 | 92.65 | 45188276 | 84.19 | [45] |

| 34 | 8DAP_Whole_Seed | seed | 58148634 | 10.14 | 92.10 | 48258631 | 82.99 | [45] |

| 35 | 20DAP_Whole_Seed | seed | 76914729 | 7.66 | 94.53 | 60236045 | 78.32 | [45] |

| 36 | 22DAP_Whole_Seed | seed | 71960325 | 8.36 | 93.25 | 61230630 | 85.09 | [45] |

| 37 | 24DAP_Whole_Seed | seed | 92168996 | 7.53 | 94.03 | 80572513 | 87.42 | [45] |

| 38 | 4DAP_Whole_Seed | seed | 100145919 | 8.22 | 93.97 | 84635434 | 84.51 | [45] |

| 39 | 14DAP_Endosperm | endosperm | 47165528 | 5.74 | 95.93 | 41130552 | 87.20 | [45] |

| 40 | 16DAP_Endosperm | endosperm | 43133667 | 24.17 | 81.93 | 36465697 | 84.54 | [45] |

| 41 | 24DAP_Endosperm | endosperm | 44105309 | 6.98 | 95.06 | 39097597 | 88.65 | [45] |

| 42 | 22DAP_Endosperm | endosperm | 50805946 | 8.39 | 93.89 | 44051966 | 86.71 | [45] |

| 43 | 20DAP_Endosperm | endosperm | 73033574 | 8.58 | 93.76 | 56588796 | 77.48 | [45] |

| 44 | 18DAP_Endosperm | endosperm | 71722169 | 9.68 | 92.92 | 62724952 | 87.46 | [45] |

| 45 | 12DAP_Endosperm | endosperm | 105002559 | 3.78 | 97.71 | 90746296 | 86.42 | [45] |

| 46 | Pro | embryo | 29413276 | 4.14 | 96.73 | 12517310 | 42.56 | [63] |

| 47 | 16DAP_Embryo | embryo | 42474548 | 25.27 | 81.01 | 35238795 | 82.96 | [45] |

| 48 | 20DAP_Embryo | embryo | 46773334 | 8.18 | 93.69 | 39847251 | 85.19 | [45] |

| 49 | 22DAP_Embryo | embryo | 54593430 | 8.38 | 94.22 | 46407023 | 85.00 | [45] |

| 50 | 18DAP_Embryo | embryo | 66441077 | 8.93 | 93.22 | 55947651 | 84.21 | [45] |

| 51 | 24DAP_Embryo | embryo | 69915678 | 7.27 | 94.61 | 59151359 | 84.60 | [45] |

| 52 | VT_Thirteenth_Leaf | leaf | 37375422 | 14.22 | 88.85 | 28643636 | 76.64 | [45] |

| 53 | V9_Eleventh_Leaf | leaf | 34439420 | 9.38 | 92.76 | 29562400 | 85.84 | [45] |

| 54 | R2_Thirteenth_Leaf | leaf | 44695525 | 11.87 | 91.31 | 35886544 | 80.29 | [45] |

| 55 | V9_Thirteenth_Leaf | leaf | 44205877 | 14.04 | 89.31 | 36100685 | 81.66 | [45] |

| 56 | V9_Eighth_Leaf | leaf | 50771168 | 13.85 | 89.38 | 42468259 | 83.65 | [45] |

| 57 | V9_Immature_Leaves | leaf | 43514876 | 25.26 | 81.13 | 35013880 | 80.46 | [45] |

| 58 | V1_4D_PE_Pooled_Leaves | leaf | 52523629 | 8.80 | 93.61 | 44510623 | 84.74 | [45] |

| 59 | V3_Topmost_leaf | leaf | 55571667 | 6.22 | 96.08 | 46448356 | 83.58 | [45] |

| 60 | V7_Bottom_of_transition_leaf | leaf | 53754587 | 5.08 | 96.09 | 46018705 | 85.61 | [45] |

| 61 | V5_Bottom_of_transition_leaf | leaf | 62309853 | 5.04 | 97.24 | 53863310 | 86.44 | [45] |

| 62 | V5_Tip of stage-2 Leaf | leaf | 79560349 | 6.88 | 94.70 | 63185974 | 79.42 | [45] |

| 63 | V7_Tip_of_transition_leaf | leaf | 84671628 | 5.19 | 95.87 | 71020587 | 83.88 | [45] |

| 64 | 6_DAS_GH_Coleoptile | leaf | 121128249 | 6.43 | 94.92 | 103474057 | 85.43 | [45] |

Gene co-expression networks can be used to identify modules based on tissue/stage-specific expression patterns. An example is a shoot apical meristem- (SAM) related expression module (Fig. 1c), which contains several well-characterized genes Rough sheath1 (Rs1) [47, 48], Knotted1 (Kn1) [49, 50] and Liguleless3 (Lg3) [51]. A total of 790 genes were co-expressed with Kn1, Rs1 and Lg3. There are 254 genes that were co-expressed with all three genes, while 401 genes were only correlated with one of the three genes. This SAM-related specific expression module is composed of genes with a distinct expression pattern across 64 different tissues/stages (Fig. 1d). Many (55 %) of the modules with at least 10 genes exhibited significant GO enrichments (Additional file 2: Table S1). This gene co-expression network provides a resource to explore the regulatory divergence of duplicate genes in maize.

Identification of duplicate genes in maize

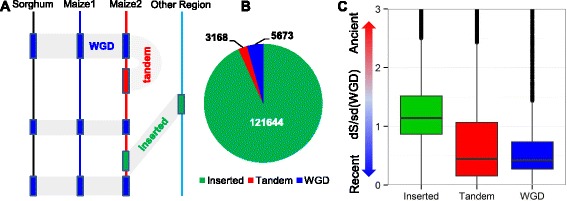

The Needleman-Wunsch algorithm with BLOSOM62 scoring matrix implemented in NCBI blast package [52] was used to identify paralogous duplicate gene pairs (See Methods) among the 39,323 annotated maize genes from the maize reference genome version 3 [44]. In total, 130,485 duplicate pairs were classified as whole genome duplications (WGD), local tandem duplications (tandem) or single gene insertions (inserted) based on grass pan genome synteny blocks [53] (Fig. 2a-b and Additional file 3: Table S2). Genes from inserted duplications are prevalent in maize, which may be due to the widespread transposon elements and transposition events in the maize genome [44]. The rate of synonymous mutations (dS) was used as a proxy for duplication age for each gene pair (Fig. 2c). Duplicate genes from WGD have the lowest mean dS and smallest variance, as expected with a single WGD event and subsequent divergence. Inserted duplicates exhibit a higher mean of dS, indicating inserted duplication occurred earlier than the recent WGD and tandem duplications (P < = 2.2e-16), while tandem duplicates show a higher variance, implying that they occurred continually over a long period of time (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Identification of duplicate genes and their relationship with duplication age. a Schematic diagram of duplication types in the maize genome relative to sorghum. Duplications were classified into three major patterns: whole genome duplication (WGD), tandem duplication and inserted duplication (located in non-syntenic positions). Boxes represent genes and the grey area shows the homologous relationship of genes between maize subgenomes or between species. “Other region” refers to a non-syntenic genomic location. b The number of duplicate gene pairs in different duplication types. c The synonomous mutation (dS) distribution of duplicate genes across different duplication types. sd(WGD) shows the standard deviation of dS of WGD pairs

Co-expression network divergence of duplicate genes

Gene duplication, which generates functional redundancy, can allow duplicates to diverge in a coding sequence or expression-level manner [9]. These duplicate divergences could play an important role in species evolution and environmental adaptation [1, 5, 8, 12]. To dissect these divergences, we examined expression patterns of the duplicate genes in the co-expression network. Maize provides an ideal system to study the co-expression network divergence of duplicate genes because of the clear history of “WGD” [28, 29] and ample available transcriptome datasets [45].

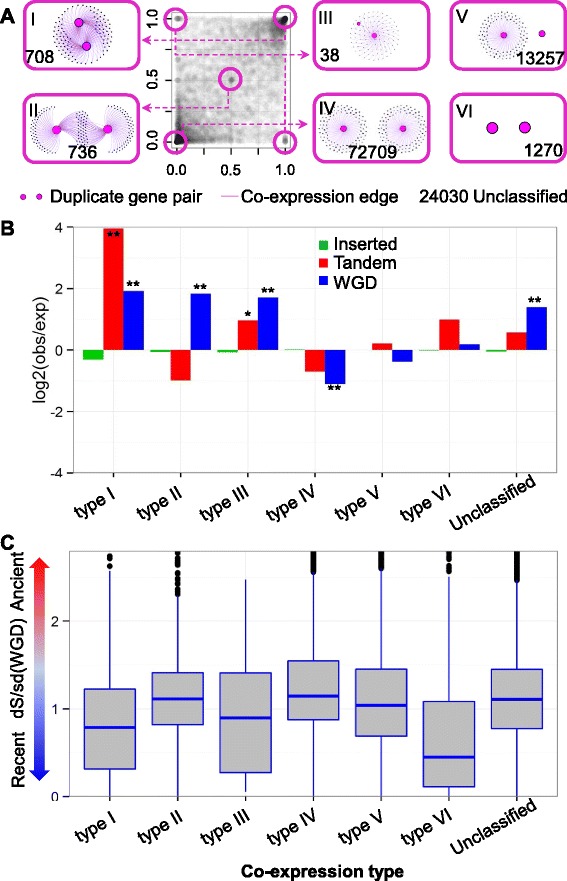

The duplicate pairs were classified into several types based on the relative co-expression relationships of both genes (Fig. 3a). For each pair of duplicate genes (gene1 and gene2), two statistics were determined, the proportion of common neighbors in the gene1 co-expression module and the proportion of common neighbors in the gene2 co-expression module. These two proportions were then used to characterize each duplicate gene pair (Fig. 3a). Four patterns of relative co-expression relationships were classified: type I – completely overlapping edges; type II- partial overlap of edges; type III - minimal overlap of edges; and type IV – non-overlapping edges for the pair (Fig. 3a). In addition, two other types of pairs were classified: type V – one gene without edges; and type VI – no edges for both members in the pair (Fig. 3a). The remaining pairs of duplicates genes, which could not be classified into any of the above six co-expression patterns but with at least 10 edges for both duplicate genes, were designated as “unclassified”. About 11 % of the duplicate pairs had no neighbors for either one or both of the members of the pair (types V and VI). The majority (56 %) of the genes that had edges for both members of the pairs have little or no overlap of edges (type IV). Duplicate genes from all six distinct co-expression groups exhibit significant functional GO enrichment (Additional file 4: Table S3). The duplicate genes with type I co-expression show strong GO enrichments in sexual reproduction, response to oxidative stress and response to chemical stimulus, while type VI is enriched for transcriptional regulators (Additional file 4: Table S3). Interestingly, genes from type IV to VI, which show extreme co-expression difference between duplicates, have GO enrichment of responses to environmental changes. Taken together, our co-expression network allowed us to classify duplicate genes in maize, providing a resource to understand potential gene regulatory divergence after gene duplication.

Fig. 3.

Regulatory divergence patterns of duplicate genes in co-expression network partitioning. a Classification of different types of co-expression patterns for duplicate genes. The proportion of shared genes (x axis and y axis) of a specific gene module is defined as the number of shared correlated genes between two duplicates divided by the total number of correlated genes for one of the duplicate genes. Each dot represents a pair of duplicate genes. A total of six co-expression regulatory patterns were classified and an example of the type of networks is visualized in the pink boxes along with the number of genes in each pattern. The other duplicate pairs were designated as “unclassified”. b The enrichment or depletion of genes in each co-expression pattern was assessed for each of the categories of gene duplications. The log2 ratio of observed to expected proportion of genes in each class is shown and “**” are used to indicate significant enrichment (P < 0.01). The expectation was calculated based on the proportion of duplicate pairs shown in Fig. 2b. c The co-expressed divergence patterns was related to the age (indicated by dS) of the duplications. The synonymous mutation rate (dS) divided by the standard deviation of dS among WGD pairs is shown for each class of co-expression relationships

The relationship between co-expression patterns and duplication types was investigated. The WGD gene pairs were most enriched in types I, II III, and the unclassified group, and are depleted in types IV and V, suggesting that many WGD pairs have common neighbors for both genes. The tandem pairs were enriched for type I genes with completely overlapping co-expression neighbors (Fig. 3b). Although duplicate pairs classified as inserted were not significantly enriched in any of the co-expression groups, they are slightly depleted in groups I, II, III, VI and unclassified, and slightly increased in group IV co-expression groups, suggesting that inserted pairs tend to have one or both members with no strong co-expression relationships or that these pairs lack common neighbors. The association between duplicate co-expression network divergence and duplication types is consistent with the results in rice and Arabidopsis [13, 18]. These results agree with the scenario where whole genome duplicates tend to maintain intact promoter regions and further express both copies, while duplicate genes from “inserted” duplication events are prone to lose promoter regions and reduce the correlated expression of duplicates [54]. Our result is also in agreement with the DNase I footprint variation between WGD and tandem duplicate genes in Arabidopsis, where whole genome duplicates have more footprints than do tandem duplicates and further allow whole genome duplicates to form more complex regulatory networks than tandem duplicates [55].

We also examined the relationship between co-expression patterns and duplication age, which was estimated using synonymous mutations (dS). The different patterns for co-expression relationships of the duplicate genes exhibit differences in duplication age (Fig. 3c). Types I, II and III (together) tend to have younger duplicates (P < 2.2E-16, compared to types IV and V). Type V has slightly older duplicates while type IV has the oldest duplicates. This may reflect that older duplications are more likely to have diverged in co-expression partners as type IV has the most divergent co-expression partners. Surprisingly, the youngest duplications seemed to be enriched for type VI. This may be due to duplicates from the youngest duplications lacking the time to set up the co-expression network with other functional genes. Overall, this result indicates that duplication age may play a role in the co-expression partitioning of duplicate genes. The longer duplicate pairs are retained, the more likely the breakdown and partitioning of their shared co-expression network.

Besides the exploration of co-expression divergence from a biological angle described above, we also employed metrics from graph theory to measure co-expression divergence in terms of the edge number in the shortest path between duplicates (a path with minimized weights of its constituent edges between two nodes), node clustering coefficient (a measure of how close its neighbors are to being a complete graph) and local node connectivity (the minimum number of edges needed to remove to eliminate all paths from one gene to its duplicate counterpart). Consistently, duplication types were related to co-expression divergences (Additional file 5: Figure S2A, B and C). WGD duplicates were more likely to be connected in the co-expression network, while duplicates from inserted duplication tended to be singletons. However, tandem duplicates showed more similarity to inserted pairs in terms of the edge number in the shortest path and local node connectivity. Moreover, younger duplications related to less co-expression divergence than older pairs (Additional file 5: Figure S2D and E).

A substantial number of inter subgenome correlations were uncovered after whole genome duplication

A pre-grass WGD shared among all grass genomes, the radiation of the grasses, and a maize lineage-specific recent WGD occurred during maize evolution [53]. Given the long period of divergence and substantial fractionation for the first two ancient large-scale genomic evolution events, we focused our analyses on the two maize subgenomes (maize1 and maize2) that were generated by the recent WGD event. Prior to a WGD event, genes from the ancestral genome would likely interact with each other to carry out their biological function, which could be inferred by co-expression correlation as clustering modules [43]. After a WGD event, co-expression correlations between genes from the same ancestral genome can be classified as subgenome intra edges and co-expression correlations between genes from the duplicated genomes can be classified as subgenome inter edges (Fig. 4a). Previous studies indicate that WGD can result in co-expression relationships among genes that are more likely to be restricted to pairs of genes from the same subgenome (i.e. intra edge correlations; Fig. 4a) [26]. Maize1 is the dominant subgenome, which ought to maintain more intra genome co-expression relationships, while the non-dominant maize2 loses functional relationships due to both gene loss and decreased gene expression. Our prediction is that maize1 will show more intra edge relationships than maize 2 intra edge or inter edge relationships between the two subgenomes. Thus, maize1 and maize2 provide a useful system to examine divergence of co-expression relationships after a WGD event and assess the extent of intra and inter edge correlations.

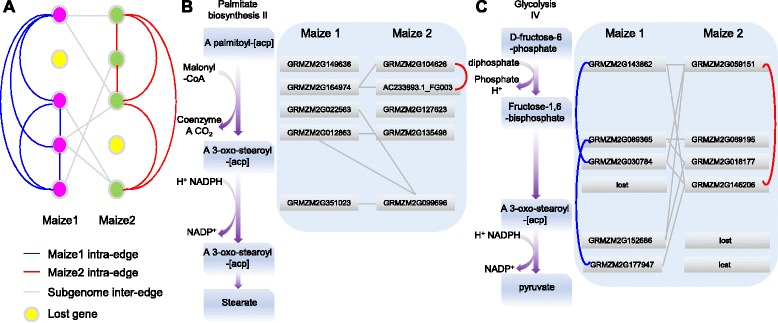

Fig. 4.

Co-expression network fractionation within metabolic pathways after maize whole genome duplication. a A schematic of a hypothetical co-expression network after a WGD event is illustrated to define potential relationships. Maize1 and maize2 intra-edges indicate the co-expression correlations among genes from the same subgenome. Subgenome inter-edges represent the co-expression relationship between genes which are from different subgenomes. The “lost” genes (in yellow) are those that have been fractionated after the recent WGD event and are missing from one of the subgenomes. Maize1 genes are shown in pink circles, while maize2 genes are in green circles. b-c Examples of co-expression networks in the stearate biosynthetic pathway where all genes were retained and the glycolysis IV pathway in which some duplicate pairs have been fractionated resulting in lost genes. Genes on the right panel encode enzymes corresponding to each pathway on the left

To characterize potential changes in the co-expression networks for metabolic pathways after a recent WGD event, we first assessed the co-expression network of 428 pathways annotated by maizeCyc [56]. The stearate biosynthetic pathway, which has retained all homeologs and the glycolysis IV pathway, which was partially fractionated following the WGD event were selected as examples for visualization (Fig. 4b-c). The extant maize stearate biosynthetic network contains seven co-expression edges and six of the seven co-expression edges are inter subgenome in nature, providing evidence of prevalence of inter subgenome correlations following the WGD event (Fig. 4b). The glycolysis IV pathway also has more inter than intra subgenome edges (Fig. 4c). Both examples demonstrate the occurrence of inter subgenome correlations after the recent WGD event.

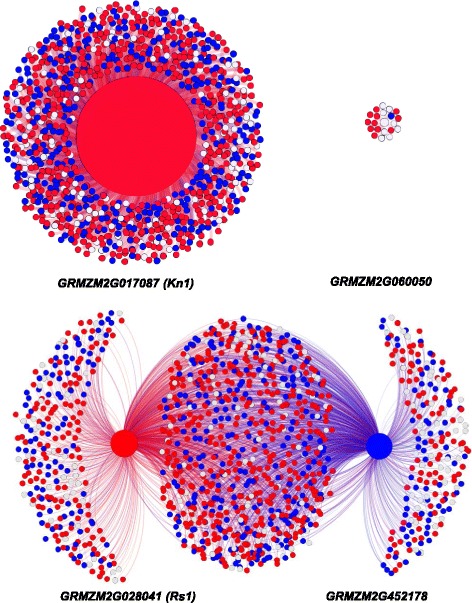

To further assess the relative prevalence of inter- and intra subgenome correlations in metabolic pathways, we explored the co-expression network divergence for 32 pathways, which have more than seven co-expression edges among genes from maize1 and maize2 subgenomes (Additional file 6: Table S4). No significant difference was observed in the density (fraction of co-expression relationships observed over the possible number of pairs) of maize1 intra-edges and maize2 intra-edges (P = 0.85, t-Test: Paired Two Sample for Means), suggesting limited divergence of co-expression relationships between the two subgenomes. Interestingly, there are equivalent number of inter subgenome edges to the total number of maize1 and maize2 intra-edges (P = 0.65 for absolute edge number; Additional file 6: Table S4). Furthermore, the overall proportion of inter and intra subgenome edges is not significantly different (P = 0.56 for the normalized edge number normalized by the number of possible pairs). We further dissected the co-expression network divergence for the duplicate pairs of the Kn1 [49, 50] and Rs1 [47, 48] genes. We observed co-expression network divergence for both duplicate pairs, the Kn1 pair showed the gene co-expression type IV pattern, while Rs1 exhibited the type II pattern (Fig. 5). However, the probability of intra and inter subgenome edges for both cases are not significantly different (P = 0.46 and 0.86 for Kn1 and Rs1 pair, respectively).

Fig. 5.

Co-expression divergence patterns for two duplicate pairs of well-known functional genes. (A) The Kn1 duplicate pair of GRMZM2G017087 (Kn1) and GRMZM2G303381 showed the co-expression type IV pattern. (B) The Rs1 duplicate pair of GRMZM2G028041 (Rs1) and GRMZM2G452178 showed co-expression type II variation. Red indicates the gene is from subgenome maize1, while blue indicates that the gene is from subgenome maize2. Grey means the gene could be anchored on either subgenome. Only genes anchored distinctly to maize1 or maize2 were used to quantify the level of inter- and intra- subgenome correlations

The prevalence of inter subgenome interactions was also assessed for all WGD pairs to determine whether the observations from metabolic pathways were representative of genome-wide trends. Separate analyses were performed for retained gene pairs and for genes that only retain the maize1 or maize2 gene. In both cases, the permutation analysis with the same number of genes and edges indicates no significant difference between the proportion of maize1 and maize2 intra-edges and a similar level of inter subgenome edges as intra subgenome edges (P = 0.83). Meanwhile, the contingency table analyses showed similar levels of inter subgenome and intra subgenome correlations (P = 0.72). Taken together, WGD in maize was accompanied by a large number of inter subgenome correlations, but in contrast exhibiting an equivalent level of intra subgenome correlations. These results are in contrast to the subgenome partitioning observed in yeast, whereby more intra subgenome correlations were observed [26]. This may be due to the fact that yeast is a single cell where all genes can directly respond to various environmental challenges. In more complex genomes, gene interactions were more likely to be regulated by transcription factors (hub genes), which may adjust the pathway in a more synergistic manner. If we assume most modules of ancestral genomes looked much like extant networks (i.e. same genes involved and same number of edges), loss of genes would remove intra-edges, and to complete metabolic pathways, these would be replaced by inter-edges. This may account for why there were large numbers of inter subgenome correlations observed given the widespread gene loss in maize subgenome2 [29]. Importantly, we do not know the ancestral state of the co-expression network prior to WGD event, so we could not postulate retention of ancestral correlations from newly evolved ones.

Ancient WGDs or paleopolyploids are widespread in flowering plants in the evolutionary history of different clades [2–4]. Comparisons of syntenic regions in Arabidopsis thaliana, Zea mays, and other flowering plants resulting from the most recent WGDs have uncovered the existence of biased gene content [29, 53, 54, 57–59]. This biased gene content between duplicate genomic regions could result from either more gene gain or more gene loss in a specific duplicate or one of the parental subgenomes [1]. One proposed model to explain the biased gene content is that the expression dominance of duplicate genes in one subgenome could make the less expressed copies in the other subgenome selectively neutral [29]. Based on the dominance of the maize1 subgenome, which would retain more biological function while maize2 would lose biological function due to gene loss and decreased expression level, we expected that maize1 subgenome would exhibit more functional dominance than maize2 in terms of more maize subgenome 1 intra edges. Unexpectedly, our co-expression network analyses identified similar levels of intra edge genome correlations in maize1 and maize2. In addition, we observed that there was a similarity in the frequency of intra and inter edge correlations, indicating that gene expression in the maize subgenomes was integrated very quickly even after the recent WGD. This result is robust to choice of cutoff for the detection of connecting genes in the co-expression network.

No subgenome asymmetry was observed in maize transcriptional network

We constructed a de novo transcriptional network including 189 modules (subnetworks) involving 31,811 annotated maize genes. Of these co-expression modules, there were 48 modules with more than 20 classified maize1 and maize2 genes, however, only two modules showed maize1 subgenome dominance where significantly more maize1 genes were enriched (Adjusted P value < = 0.05). The proportion (4 %) of subgenome dominant modules is significantly lower than that (92 %) in allohexaploid bread wheat [27] (Additional file 7: Table S5). Hub genes, which are connected with thousands of other genes in network, may play a critical role in biological function of organisms. Furthermore, 1000 permutation tests of node degree in the maize co-expression network uncovered 525 highly connected genes in the network (hub genes) (Additional file 8: Table S6). However, these hub genes were not significantly more likely to show a subgenome bias (Chi-Square Test; P = 0.13), which is also different from that in wheat. Unlike wheat, the co-expression network in maize exhibited no subgenome asymmetry, which may be due to the relative older age of the maize whole genome duplication [44, 60]. Maize tetraploidy occurred between 5 and 12 million years ago, while allohexaploid genome bread wheat has experienced much less time (2.5 ~ 4 million years) to diverge [61]. Compared to wheat, the increased time maize had to merge subgenomes resulted in a genome that is highly integrated from a transcriptional viewpoint. Taken together, our results indicate that the maize genome does not have subgenome dominance in terms of transcriptional networks. However, our study provides a comprehensive landscape of co-expression divergence of duplicate genes after WGD in maize.

Methods

Transcriptome dataset in maize

All transcriptome datasets were publicly available and downloaded from NCBI Sequence Read Archive [45, 62–64]. A total of 64 experiments generated by next generation sequencing (NGS) were obtained from different tissues or development stages of maize reference inbred B73 (Table 1). The transcriptome dataset consists of both single-end reads and pair-end reads with read length ranging from 50 to 110 bp. Each experiment (tissue/stage) had 2 to 3 biological replicates. Each biological replicate was analyzed separately and the average normalized expression level of all the biological replicates was obtained to represent the expression-level of specific tissue/stage.

Transcriptome profiling and co-expression network construction

After downloading all the transcriptome datasets, trimmomatic [65] was employed to remove all the adapter sequences. Then, low quality sequences were removed using Fastx-Toolkit [66]. High quality NGS reads of each biological replicate for each tissue/stage were mapped onto annotated gene region space of the maize reference genome (AGP v3) [44] using RSEM [67] with parameters “-p 8 --bowtie2 --estimate-rspd --append-names --output-genome-bam ”. The statistic “TPM” (Transcripts Per Million) was adopted as the proxy of normalized expression-level. A matrix (39,323 annotated maize genes X 64 transcriptome datasets) of a transcriptome profiling dataset across 64 different tissues/stages was used for further analyses.

We considered a gene was expressed if it had TPM > 0 in at least three tissues or TPM > 5 in at least one tissue. A total of 37,649 genes were determined to be expressed across 64 different tissues/stages of maize reference inbred B73. To reduce the weight of highly expressed genes on correlation coefficients, we transformed TPM values using inverse hyperbolic sine function, which compressed large values while preserving the relative magnitude of small values [45]. Co-expression networks were constructed by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients between all pairs of genes (37,649 × 37,649):

Where i, j = 1, …, 37,649 and i ≠ j. The set of correlations was then transformed by Fisher transformation [68], which yields approximately normal distribution [38]:

Fisher transformed values were then standard normalized such that the resulting co-expression edge distribution had a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. A set of cutoffs of Z score (1.5, 2.0, 2.5 and 3.0) was used as the threshold for the detection of significant edge (interaction) between genes. The co-expression networks were created and analyzed using the Sleipnir C++ library [69]. The software Cytoscape 3.0.2 [70] was used for visualization of the co-expression networks. The co-expression network could be explored through the COB database [46]. Due to the memory limitation of local computers, only a small fraction of co-expression connections that users query can be rendered. However, the user can download the full co-expressed gene list using “Table View” of the COB database.

Duplicate genes and the identification of expression-level variation and co-expression divergence pattern

Maize paralogous duplicate genes were identified using NCBI blast + [52], which adopted the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm with the BLOSOM62 scoring matrix. The candidate paralogous pairs were extracted using the cutoff E value < =1.0E-05 based on the protein sequence alignment of all maize annotated genes. Furthermore, if the proportion of aligned protein amino acid length to the full protein length is more than 40 % for both genes, the significant gene pair was considered as a paralogous duplicate. Then, the duplicate genes were compared and merged with syntenic gene blocks in maize [53]. For the paralogous duplicates, the protein sequence was translated into aligned codons, and further codeml of the PAML software package [71] was used for the calculation of synonymous mutation rate (dS) with its default parameter sets. Only duplicate pairs, of which both genes were expressed across 64 different tissues/stages, were kept for further analyses of co-expression network divergence.

Co-expression network divergence was examined by comparing the sharing neighbors between two duplicates. First, by exploring the co-expression networks, we summarized the number of nodes (correlated genes) of duplicate genes. Then, we computed the proportion of common neighbors (same correlated genes) for the members from any pair of duplication. The proportion of shared correlated genes of a specific gene module is defined as the number of shared correlated genes between two duplicates divided by the total number of correlated genes for one of the duplicate genes. Specifically, for a paralogous duplicate pair (gene1 and gene2), the statistic gene1common represents the proportion of common neighbors with gene2 for gene1, while gene2common indicates the proportion of common neighbors with gene1 for gene2. Both gene1common and gene2common range from 0 (without any common neighbors) to 1 (sharing all the neighbors) in the co-expression network. For the paralogous pairs where both duplicates have at least 10 neighbors (correlated genes), if , type I – completely sharing neighbors with each other was classified; if , type II – partial sharing of neighbors was classified; if , or , type III – minimal sharing of neighbors was classified; if , type IV – non-sharing neighbor for the pair was classified; otherwise, the paralogous pairs where both duplicates have at least ten neighbors (correlated genes) were designated as “unclassified”. If one duplicate has at least ten neighbors while the counterpart has no neighbors, such paralogous pairs were classified as type V. If both duplicates have no neighbors (singleton), such paralogous pairs were classified as type VI. A total of seven co-expression regulatory patterns (type I ~ VI and unclassified), were identified, while other paralogous duplicate pairs which do not satisfy the above criteria were excluded in our further analyses. Gene Ontology enrichment analyses for the genes from different co-expression divergence groups were performed using AgriGO [72].

Furthermore, to detect the co-expression divergence using graph theory, we also adopted the shortest network path, edge connectivity of a duplicate pair, and local clustering coefficient of genes in the co-expression network for the representation of co-expression divergence in the further analyses. The calculation was conducted using igraph R package [73].

We employed a set of Z score cutoffs (1.5, 2.0, 2.5 and 3.0) for the classification of co-expression divergence. Given the peak of proportion of type IV at around 2.0, the statistic significance, and the relative less number of unclassified co-expression type (Additional file 1: Figure S1), we employed Z score cutoff of 2.5 for the construction of maize co-expression network and further analyses.

Duplication type, age and their relationships with regulatory divergence of duplicate genes

Duplication type and the manner that duplication occurred were obtained by analyzing maize updated syntenic gene blocks [53]. Three major duplication types were identified: “WGD” is defined as whole genome duplication; “tandem” for tandem duplication; and “inserted” for duplicate genes located in non-syntenic genomic regions (Fig. 2a). Synonymous mutation rate, which is an indicator of duplication age, was calculated using PAML [71]. All the relationship analyses were conducted in R [74].

Co-expression edge fractionation in maize transcriptional network

Maize metabolic pathways were downloaded from MaizeCyc 2.2 [56, 75]. The metabolic pathways with at least two pairs of duplicate genes generated by recent WGD event were kept for the co-expression fractionation analysis. Maize1 intra edges, maize2 intra edges and inter subgenome edges were counted and summarized to identify different types of edges in each metabolic pathway. Paired two sample t-test was conducted on 32 metabolic pathways with at least seven edges for the comparison between maize1 intra edges, maize2 intra edges and inter subgenome edges. The overall genome-wide trend of co-expression edge fractionation was investigated based on two different sets of WGD duplicate genes: one is the retained gene pair, and the other is genes that have been subjected to fractionation. In both cases the frequency of inter subgenome correlations and the frequency of intra subgenome interactions were calculated and compared with each other. Permutation analysis with the same number of genes and edges was performed to test if the observation that more inter subgenome edges than intra edges is significant. Similar analyses with less stringent Z score cutoffs (1.5 and 2.0) were conducted and showed consistent results.

Subgenome enrichment test in maize co-expression network modules

The mcl markov cluster algorithm was employed to distinguish co-expression network modules with default parameters [76]. According to maize pan genome information [53], we summarized the number of maize1 genes and maize2 genes, and then applied a Chi-square test to discriminate if specific subgenome genes were enriched in any co-expression network modules with at least 20 maize1 and maize2 genes. The significance of the Chi-square test was adjusted through Bonferroni correction.

Hub genes, which had significantly more connected genes than the average in the network, were analyzed in our study. The degree (the number of the co-expressed genes) of each gene in the maize co-expression network was obtained by in-house perl scripts. Further, 1000 permutation tests with the same number of genes (nodes) and significant correlations (edges) were conducted to obtain the cutoff (α = 0.05) of highly connected genes (hub genes) in the maize co-expression network. A cutoff of 2706 was obtained for the identification of 525 hub genes in our study. Finally, Chi-square tests on the 525 hub genes were performed to check if these genes were enriched in maize1 or maize2. These tests were conducted after taking into account the gene number differences between maize1 (15,231) and maize2 (9553).

Conclusions

We developed a co-expression network for the maize inbred line B73 from 64 different tissues/stages B73 and used the network to explore the expression fate of duplicate genes. There are four key findings from our work: (1) WGD, tandem and inserted gene duplications exhibit different regulatory divergence; (2) co-expression variation was greater in older duplicate genes than younger duplicates; (3) more co-expression divergence was observed in inserted duplications and and this divergence was also related to the age of the duplication; and (4) maize1 and maize2 exhibit similar levels of intra and inter subgenome correlations, indicating that there is no subgenome dominance in the network.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute. We are grateful to Dr. Shawn M. Kaeppler (University of Wisconsin, Madison) and Dr. Candice Hirsch (University of Minnesota) for sharing their transcriptome datasets before public release.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Genetic Networks Regulating Structure and Function of the Maize Shoot Apical Meristem in maize-NSF #1238142). R.B., R.S., and C.L.M. were partially supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (IOS 1126950, DBI 0953881). Funding for open access charge: National Science Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

The RNA sequencing data used in our study (Table 1) are public available and deposited in the NCBI database. The co-expression network data are available at Cob SAM database [46]. The other supporting data were included as Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8.

Authors’ contributions

LL, CM, NS, and GM conceived the project idea. LL, RB, and RS performed data analysis. LF, NS, GS and PS edited the manuscript. LL and GM wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- DB

DataBase

- Mya

Million year ago

- WGD

Whole genome duplication

Additional files

The proportion of different co-expression divergence patterns identified across different cutoffs of Z score. (PDF 64 kb)

GO enrichment for genes from different co-expression modules. (XLSX 365 kb)

Duplicate genes. (XLSX 19372 kb)

GO Enrichment for duplicate genes with different co-expression types. (XLSX 21 kb)

Co-expression divergence in terms of shortest network path, edge connectivity of a duplicate pair, and local clustering coefficient. (A) WGD duplicates had significantly shorter path edges than inserted and tandem duplicate genes. (B) WGD duplicates had significantly higher edge connectivity than inserted and tandem duplicate genes. (C) Maize1 and maize2 genes had significantly lower local clustering coefficient than non-syntenic genes (usually generated by inserted and tandem duplications). (D) and (E) Shortest network path and edge connectivity of a duplicate pair were associated with synonymous mutation rate (dS). (PDF 740 kb)

Co-expression divergence in metabolic pathways. a-the number of duplicate pairs in the metabolic pathway; b-the number of co-expression edges in the metabolic pathway; c-the possibility of maize1 intra-edges; d-the possibility of inter-subgenome co-expression edges; e-the possibility of maize2 intra-edges; f-the possibility of total intra-edges in metabolic pathway. (XLSX 13 kb)

Subgenome gene enrichment in co-expression network modules. (XLSX 12 kb)

Subgenome gene enrichment in the set of hub genes. (XLSX 522 kb)

Contributor Information

Lin Li, Email: lixx1601@umn.edu.

Roman Briskine, Email: roman.briskine@gmail.com.

Robert Schaefer, Email: schae234@gmail.com.

Patrick S. Schnable, Email: schnable@iastate.edu

Chad L. Myers, Email: cmyers@cs.umn.edu

Lex E. Flagel, Email: flag0010@gmail.com

Nathan M. Springer, Email: springer@umn.edu

Gary J. Muehlbauer, Email: Muehl003@umn.edu

References

- 1.Freeling M. Bias in plant gene content following different sorts of duplication: tandem, whole-genome, segmental, or by transposition. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:433–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kondrashov FA, Rogozin IB, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Selection in the evolution of gene duplications. Genome Biol. 2002;3:8. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-2-research0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J. Evolution by gene duplication: an update. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003;18:292–8. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00033-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiao Y, Wickett NJ, Ayyampalayam S, Chanderbali AS, Landherr L, Ralph PE, et al. Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Nature. 2011;473:97–100. doi: 10.1038/nature09916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magadum S, Banerjee U, Murugan P, Gangapur D, Ravikesavan R. Gene duplication as a major force in evolution. J Genet. 2013;92:155–61. doi: 10.1007/s12041-013-0212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohno DS. Evolution by gene duplication. Springer: Berlin Heidelberg; 1970. pp. 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu X, Wang Y, Gu J. Age distribution of human gene families shows significant roles of both large- and small-scale duplications in vertebrate evolution. Nat Genet. 2002;31:205–9. doi: 10.1038/ng902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanc G, Wolfe KH. Functional divergence of duplicated genes formed by polyploidy during Arabidopsis evolution. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1679–91. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore RC, Purugganan MD. The evolutionary dynamics of plant duplicate genes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290:1151–5. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flagel LE, Wendel JF. Evolutionary rate variation, genomic dominance and duplicate gene expression evolution during allotetraploid cotton speciation. New Phytol. 2010;186:184–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGrath CL, Lynch M. Evolutionary significance of whole-genome duplication. In: Soltis PS, Soltis DE, editors. Polyploidy and genome evolution. Springer: Berlin Heidelberg; 2012. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W-H, Yang J, Gu X. Expression divergence between duplicate genes. Trends Genet. 2005;21:602–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu Z, Rifkin SA, White KP, Li W-H. Duplicate genes increase gene expression diversity within and between species. Nat Genet. 2004;36:577–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piatigorsky J, Wistow G. The recruitment of crystallins: new functions precede gene duplication. Science. 1991;252:1078–9. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes AL. The evolution of functionally novel proteins after gene duplication. Proc Biol Sci. 1994;256:119–24. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Force A, Lynch M, Pickett FB, Amores A, Yan YL, Postlethwait J. Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics. 1999;151:1531–45. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casneuf T, De Bodt S, Raes J, Maere S, Van de Peer Y. Nonrandom divergence of gene expression following gene and genome duplications in the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-2-r13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duarte JM, Cui L, Wall PK, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Leebens-Mack J, et al. Expression pattern shifts following duplication indicative of subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization in regulatory genes of Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:469–78. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganko EW, Meyers BC, Vision TJ. Divergence in expression between duplicated genes in Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:2298–309. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Adams KL. Expression partitioning between genes duplicated by polyploidy under abiotic stress and during organ development. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1669–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou C, Lehti-Shiu MD, Thomashow M, Shiu S-H. Evolution of stress-regulated gene expression in duplicate genes of Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S-L, Baute GJ, Adams KL. Organ and cell type-specific complementary expression patterns and regulatory neofunctionalization between duplicated genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:1419–36. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian W, Liao B-Y, Chang AY-F, Zhang J. Maintenance of duplicate genes and their functional redundancy by reduced expression. Trends Genet. 2010;26:425–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woodhouse MR, Cheng F, Pires JC, Lisch D, Freeling M, Wang X. Origin, inheritance, and gene regulatory consequences of genome dominance in polyploids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5283–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402475111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conant GC, Wolfe KH. Functional partitioning of yeast co-expression networks after genome duplication. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfeifer M, Kugler KG, Sandve SR, Zhan B, Rudi H, Hvidsten TR, et al. Genome interplay in the grain transcriptome of hexaploid bread wheat. Science. 2014;345:1250091. doi: 10.1126/science.1250091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei F, Coe E, Nelson W, Bharti AK, Engler F, Butler E, et al. Physical and genetic structure of the maize genome reflects its complex evolutionary history. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schnable JC, Springer NM, Freeling M. Differentiation of the maize subgenomes by genome dominance and both ancient and ongoing gene loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4069–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101368108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes TE, Langdale JA, Kelly S. The impact of widespread regulatory neofunctionalization on homeolog gene evolution following whole-genome duplication in maize. Genome Res. 2014;24:1348–55. doi: 10.1101/gr.172684.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pophaly SD, Tellier A. Population level purifying selection and gene expression shape subgenome evolution in maize. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:3226–35. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang P, Chopra S, Peterson T. A segmental gene duplication generated differentially expressed myb-homologous genes in maize. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2311–22. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang G, Zhong M, Wang J, Zhang J, Tang Y, Wang G, et al. Genome-wide identification, splicing, and expression analysis of the myosin gene family in maize (Zea mays) J Exp Bot. 2014;65:923–38. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiong Y, Mei W, Kim E-D, Mukherjee K, Hassanein H, Barbazuk WB, et al. Adaptive expansion of the maize maternally expressed gene (Meg) family involves changes in expression patterns and protein secondary structures of its members. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:204. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0204-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao Y, Cai M, Zhang X, Li Y, Zhang J, Zhao H, et al. Genome-wide identification, evolution and expression analysis of mTERF gene family in maize. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ficklin SP, Feltus FA. Gene coexpression network alignment and conservation of gene modules between Two grass species: maize and rice. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:1244–56. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.173047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mochida K, Uehara-Yamaguchi Y, Yoshida T, Sakurai T, Shinozaki K. Global landscape of a co-expressed gene network in barley and its application to gene discovery in Triticeae crops. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52:785–803. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swanson-Wagner R, Briskine R, Schaefer R, Hufford MB, Ross-Ibarra J, Myers CL, et al. Reshaping of the maize transcriptome by domestication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:11878–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201961109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Downs GS, Bi Y-M, Colasanti J, Wu W, Chen X, Zhu T, et al. A developmental transcriptional network for maize defines coexpression modules. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:1830–43. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.213231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaefer RJ, Briskine R, Springer NM, Myers CL. Discovering functional modules across diverse maize transcriptomes using COB, the Co-expression browser. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e99193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Movahedi S, Van de Peer Y, Vandepoele K. Comparative network analysis reveals that tissue specificity and gene function are important factors influencing the mode of expression evolution in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:1316–30. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.177865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mutwil M, Klie S, Tohge T, Giorgi FM, Wilkins O, Campbell MM, et al. PlaNet: combined sequence and expression comparisons across plant networks derived from seven species. Plant Cell. 2011;23:895–910. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.083667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moreno-Risueno MA, Busch W, Benfey PN. Omics meet networks - using systems approaches to infer regulatory networks in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schnable PS, Ware D, Fulton RS, Stein JC, Wei F, Pasternak S, et al. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science. 2009;326:1112–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1178534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sekhon RS, Briskine R, Hirsch CN, Myers CL, Springer NM, Buell CR, et al. Maize gene atlas developed by RNA sequencing and comparative evaluation of transcriptomes based on RNA sequencing and microarrays. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.cobSam [http://csbio.cs.umn.edu/cobSam]. Accessed 31 Oct 2016.

- 47.Becraft PW, Freeling M. Genetic analysis of Rough sheath1 developmental mutants of maize. Genetics. 1994;136:295–311. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.1.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneeberger RG, Becraft PW, Hake S, Freeling M. Ectopic expression of the knox homeo box gene rough sheath1 alters cell fate in the maize leaf. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2292–304. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vollbrecht E, Veit B, Sinha N, Hake S. The developmental gene Knotted-1 is a member of a maize homeobox gene family. Nature. 1991;350:241–3. doi: 10.1038/350241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vollbrecht E, Reiser L, Hake S. Shoot meristem size is dependent on inbred background and presence of the maize homeobox gene, knotted1. Development. 2000;127:3161–72. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muehlbauer GJ, Fowler JE, Girard L, Tyers R, Harper L, Freeling M. Ectopic expression of the maize homeobox gene liguleless3 alters cell fates in the leaf. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:651–62. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinf. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schnable JC, Freeling M, Lyons E. Genome-wide analysis of syntenic gene deletion in the grasses. Genome Biol Evol. 2012;4:265–77. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, Wang X, Tang H, Tan X, Ficklin SP, Feltus FA, et al. Modes of gene duplication contribute differently to genetic novelty and redundancy, but show parallels across divergent angiosperms. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arsovski AA, Pradinuk J, Guo XQ, Wang S, Adams KL. Evolution of cis-regulatory elements and regulatory networks in duplicated genes of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:2982–91. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Monaco MK, Sen TZ, Dharmawardhana PD, Ren L, Schaeffer M, Naithani S et al. Maize Metabolic Network Construction and Transcriptome Analysis. Plant Genome. 2013;6:0.

- 57.Thomas BC, Pedersen B, Freeling M. Following tetraploidy in an Arabidopsis ancestor, genes were removed preferentially from one homeolog leaving clusters enriched in dose-sensitive genes. Genome Res. 2006;16:934–46. doi: 10.1101/gr.4708406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodhouse MR, Schnable JC, Pedersen BS, Lyons E, Lisch D, Subramaniam S, et al. Following tetraploidy in maize, a short deletion mechanism removed genes preferentially from one of the two homeologs. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sankoff D, Zheng C, Zhu Q. The collapse of gene complement following whole genome duplication. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:313. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Swigonová Z, Lai J, Ma J, Ramakrishna W, Llaca V, Bennetzen JL, et al. Close split of sorghum and maize genome progenitors. Genome Res. 2004;14:1916–23. doi: 10.1101/gr.2332504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang S, Sirikhachornkit A, Su X, Faris J, Gill B, Haselkorn R, et al. Genes encoding plastid acetyl-CoA carboxylase and 3-phosphoglycerate kinase of the Triticum/Aegilops complex and the evolutionary history of polyploid wheat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8133–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072223799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.NCBI SRA [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/]. Accessed 31 Oct 2016.

- 63.Takacs EM, Li J, Du C, Ponnala L, Janick-Buckner D, Yu J, et al. Ontogeny of the maize shoot apical meristem. Plant Cell. 2012;24:3219–34. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.099614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eveland AL, Goldshmidt A, Pautler M, Morohashi K, Liseron-Monfils C, Lewis MW, et al. Regulatory modules controlling maize inflorescence architecture. Genome Res. 2014;24:431–43. doi: 10.1101/gr.166397.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fastx-Toolkit [http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/]. Accessed 31 Oct 2016.

- 67.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinf. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huttenhower C, Hibbs M, Myers C, Troyanskaya OG. A scalable method for integration and functional analysis of multiple microarray datasets. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2890–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huttenhower C, Schroeder M, Chikina MD, Troyanskaya OG. The Sleipnir library for computational functional genomics. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1559–61. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–91. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Du Z, Zhou X, Ling Y, Zhang Z, Su Z. agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W64–70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Csardi G, Nepusz T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal Complex Syst. 2006;1695:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 74.R Language [http://www.r-project.org/]. Accessed 31 Oct 2016.

- 75.Maize Metabolite Pathway Database [http://maizecyc.maizegdb.org/]. Accessed 31 Oct 2016.

- 76.Van Dongen S. Graph clustering via a discrete uncoupling process. SIAM J Matrix Anal Appl. 2008;30:121–41. doi: 10.1137/040608635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The RNA sequencing data used in our study (Table 1) are public available and deposited in the NCBI database. The co-expression network data are available at Cob SAM database [46]. The other supporting data were included as Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8.