Abstract

This study examined the moderating role of family instability in relations involving destructive interparental conflict, children’s internal representations of insecurity in the family system, and their early school maladjustment. Two hundred forty-three preschool children (M age = 4.60 years; 56% girls) and their families participated in this multi-method (i.e., observations, structured interview, surveys) multi-informant (i.e., observer, parent, teacher), longitudinal study. Findings indicated that the mediational role of children’s insecure family representations in the pathway between destructive interparental conflict and children’s adjustment problems varied significantly depending on the level of family instability. Interparental conflict was specifically associated with insecure family representations only under conditions of low family instability. In supporting the role of family instability as a vulnerable-stable risk factor, follow up analyses revealed that children’s concerns about security in the family were uniformly high under conditions of heightened instability regardless of their level of exposure to interparental conflict.

Keywords: interparental conflict, family instability, emotional security theory, internal representations, school adjustment

Destructive interparental conflict characterized by intense, prolonged hostility is a risk factor for a wide range of behavioral, social, and academic problems for children (e.g., Cummings & Davies, 2010; Gordis, Margolin, & John, 2001). According to emotional security theory (EST), interparental conflict increases children’s vulnerability to adjustment problems by undermining their goal of preserving their safety and security in interparental and parent-child relationships (Davies & Cummings, 1994). Although maintaining security in family relationships is theorized to be a latent goal, EST posits that children’s internal representations of family relationships are reliable barometers of their level of insecurity. Thus, consistent with other conceptualizations (Bretherton, 1985; Oppenheim, 2006), children’s insecurity in the family is reflected in their internal representations of family conflicts and challenges as having prolonged, deleterious consequences for their own welfare and the integrity of the family unit (Forman & Davies, 2005). In accord with EST, research has shown that children’s insecure internal representations of interparental relationships mediate associations between interparental conflict and their adjustment problems (Cummings & Davies, 2002; Sturge-Apple, Davies, Winter, Cummings, & Schermerhorn, 2008).

However, significant gaps remain in testing key hypotheses in EST. Research on interparental conflict has predominantly focused on examining insecurity in specific family (i.e., interparental, parent-child) relationships (e.g., Cummings, Schermerhorn, Keller, & Davies, 2008; Sturge-Apple et al., 2008). Therefore, little is known about how interparental conflict may increase children’s vulnerability to maladjustment by undermining their appraisals of the broader family to serve as a source of security. Family process models further posit that family-level representations of security and their associations with maladjustment are rooted in experiences with multiple family factors (e.g., unstable family events) that extend beyond exposure to interparental conflict (e.g., Forman & Davies, 2003; Oppenheim, 2006). Yet, there is a paucity of research on how destructive interparental conflict operates with other family factors as predictors in mediational pathways involving children’s insecurity in the family and adjustment problems. Thus, our goal in this paper was to examine how the interplay between children’s experiences with destructive interparental conflict and family instability informs an understanding of their insecure representations of the family and maladjustment.

Insecure Family Representations as Mediators of Interparental Conflict

The few empirical tests of insecure family representations as mediators of interparental conflict have commonly treated children’s appraisals of interparental and parent-child relationships as distinct factors (e.g., Cummings et al., 2008; Sturge-Apple et al., 2008). For example, research has shown that interparental conflict is consistently associated with children’s insecure representations of both interparental and parent-child relationships. However, when examined as simultaneous predictors of child functioning, the two forms of insecure representations were inconsistent mediators in pathways between interparental conflict and children’s school adjustment (Sturge-Apple et al., 2008). In these models, common variance between interparental and parent-child relationships is eliminated in an effort to examine whether each specific construct evidences unique associations with children’s school functioning. However, because conflict in any dyad tends to proliferate to undermine other family relationships, the collective analysis of the family unit as a source of security may provide a more comprehensive assessment of children’s emotional insecurity (Forman & Davies, 2005).

Accordingly, our first aim was to test the hypothesis that children’s insecure representations of multiple family relationships (i.e., interparental, parent-child) mediate associations between interparental conflict and their adjustment problems. Although no investigations, to our knowledge, have directly tested this mediational pathway, some empirical findings provide indirect support for our hypothesis. For example, Cummings, Koss, and Davies (2015) found that adolescents’ perceptions of insecurity in the family unit mediated the association between triadic conflicts (i.e., mother, father, and teen) and their adjustment problems. However, it is unclear whether these pathways operate in the context of conflicts between parents that do not directly involve the children. Likewise, another study identified bivariate associations between: (a) interparental conflict and teen appraisals of insecurity in the family and (b) their appraisals of family-level insecurity and psychological problems, but did not directly test mediation in a multivariate framework (Forman & Davies, 2005).

The Role of Family Instability in Mediational Paths of Insecure Family Representations

Although EST posits that children’s insecurity in family relationships is a mechanism underlying the vulnerability of children exposed to destructive interparental conflict, the meaning interparental conflict has for children’s safety and security in the family system is also proposed to depend, in part, on the broader family climate (Davies, Winter, & Cicchetti, 2006). From a child’s perspective, signs of broader family vulnerabilities may not only directly amplify their concerns about safety in the family, but also change how children process and interpret the consequences interparental conflict has for their own well-being in the family (Cummings & Davies, 2010). Although rarely investigated in models of emotional insecurity, EST proposes that family instability is a key vulnerability factor that may alter mediational pathways of emotional security. Family instability is specifically characterized by disruptive events that undermine the predictability, consistency, and cohesiveness of family life for children. Notably, the cumulative frequency of unstable events in the form of caregiver intimate relationship changes, residential mobility, changes in caregivers, and death of close family members have been consistently linked with a variety of negative outcomes for children (e.g., Ackerman, Kogos, Youngstrom, Schoff, & Izard, 1999; Bachman, Coley, & Carrano, 2011; Cavanagh & Huston, 2008). Because frequent unstable family events are regarded as concrete manifestations of a fragile, chaotic family system, family process models have posited that family instability increases children’s vulnerability to adjustment difficulties by amplifying their representations of the family unit as unpredictable and threatening (e.g., Ackerman et al., 1999). To our knowledge, the only study to test this hypothesis identified adolescent appraisals of family insecurity as a mediator between family instability and their psychological problems (Forman & Davies, 2003).

In building on the existing research, our goal was to examine, for the first time, the interplay between interparental conflict and family instability in predicting children’s family-level representations and adjustment problems. At the additive effects level, we hypothesized that family instability and interparental conflict would each uniquely predict children’s insecure representations of the family. Although studies have yet to examine interparental conflict and family instability as simultaneous predictors of children’s security in family relationships, bivariate analyses have identified each family factor as a correlate of children’s insecure family appraisals (Forman & Davies, 2005). Moreover, within the EST framework, it is possible that destructive interparental conflict and unpredictable family events may each serve as distinctive threats to children’s emotional security in the family unit. For example, frightening behaviors displayed by parents during hostile conflicts are theorized to engender representations of parents as sources of threat in the family. In contrast, exposure to unstable life events may signify to children that parents are unable to establish and maintain predictability and safety in the family unit (Davies & Sturge-Apple, 2007).

At the level of interaction models, even less is known about how these two family risk factors operate multiplicatively in pathways involving children’s security in the family and their psychological adjustment. In the only study to examine the interaction between family instability and interparental conflict in predicting children’s emotional insecurity, Davies, Harold, Goeke-Morey, and Cummings (2002) identified family instability as a potentiating factor in associations between interparental conflict and children’s emotional insecurity in the interparental relationship. Interparental conflict was a significantly stronger predictor of children’s insecurity within families experiencing high levels of family instability. However, due to the dearth of research on the multiplicative interplay between interparental conflict and family instability in understanding children’s family representations, questions remain as to how instability may specifically moderate the risk posed by destructive interparental conflict. In drawing on the developmental psychopathology taxonomy of vulnerability effects (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000), we specifically test the relative viability of two models of potentiation.

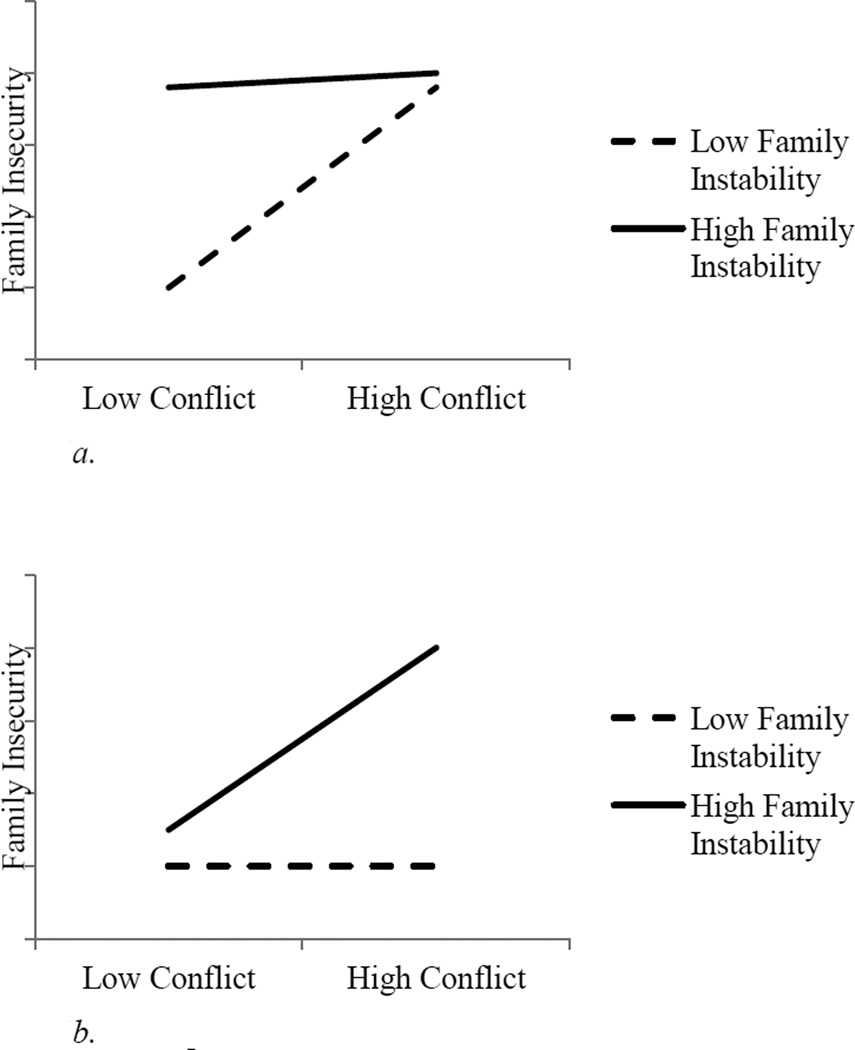

As shown in Figure 1a, the vulnerable-stable model proposes that the combination of destructive interparental conflict and family instability does not incrementally increase children’s disadvantage above and beyond either form of family risk considered singly. Due to the mutual potency of conflict and instability as risk factors, interparental conflict is proposed to predict higher levels of children’s insecurity only when instability is low. Children’s concerns about security in the family are likely to be uniformly high under conditions of heightened instability regardless of their level of exposure to interparental conflict. In the second form of moderation shown in Figure 1b, the vulnerable-reactive model proposes that high family instability amplifies predictive pathways between destructive interparental conflict and children’s insecurity in the family. Whereas conflict is a relatively weak predictor of changes in children’s adjustment problems at low levels of instability, it may take an exponentially greater toll on children when they are exposed to highly unstable family environments.

Figure 1.

a. Conceptual illustration of the vulnerable-stable form of moderation.

b. Conceptual illustration of the vulnerable-reactive form of moderation.

Mediational Paths of Insecure Family Representations during the Transition to School

Our objective was to identify the nature of associations between children’s experiences with interparental conflict and family instability, their insecure representations of their families, and their maladjustment during the transition to school based on several developmental considerations. Empirical evidence suggests that the risk posed by exposure to both interparental conflict and family instability is heightened during the preschool years (e.g., Ackerman et al., 1999; Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003). In comparison to periods of preadolescence and adolescence, the preschool and early school years are marked by experiences of greater fear and threat in response to family conflict and a more narrow skill set for coping or regulating distress (e.g., Grych, 1998; Jouriles, Spiller, Stephens, McDonald, & Swank, 2000). Moreover, as children progress through the preschool and early school period, advances in the use of symbolism, language ability, and understanding of interpersonal origins of emotional states provide a foundation for more sophisticated, differentiated ways of processing and internally representing the relational consequences and meaning of family events, relative to their younger counterparts (Ayoub et al., 2006; Toth, Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Sturge-Apple, 2009). Thus, children’s insecurity in the face of high levels of interparental conflict and family instability may be particularly likely to be manifested in their negative internal representations of the family.

Script theory proposes that children rely more heavily on prior family representations as a way to simplify and comprehend challenging interpersonal contexts (Johnston, Roseby, & Kuehnle, 2009). Thus, by virtue of their novelty, complexity, and stressfulness, school settings are salient contexts for the use of family representations as guides for functioning. Accordingly, our objective was to utilize a longitudinal design to examine changes in school adjustment problems during the transition to kindergarten as outcomes of the mediational role of children’s insecure representations of the family. Consistent with multi-dimensional models of school readiness, we operationalized school maladjustment as encompassing difficulties in behavioral (e.g., externalizing behaviors), social (e.g., peer relationship impairments), and academic (i.e., attention difficulties) domains (e.g., Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999).

In summary, the aims of the present study were to: (1) test children’s insecure representations of the family as a mediator in the link between interparental conflict and children’s school maladjustment and (2) examine family instability as a moderator in the mediational pathway. The limited corpus of studies on family-level representations has predominantly relied on survey measures to examine associations with family factors and child psychological adjustment (e.g., Forman & Davies, 2003, 2005). Therefore, to reduce the operation of common method and informant variance in tests of all hypotheses, we utilized a multi-method (i.e., surveys, interviews, observations), multi-informant (i.e., observer, parent, teacher) approach to assessing the key constructs. To more rigorously test hypotheses, demographic characteristics (i.e., parent education level, child sex) and school adjustment problems during the preschool period were included as covariates in the analyses. Additionally, given empirical documentation of associations between parenting difficulties and children’s internal representations (Sturge-Apple et al., 2008; Toth et al., 2009), we also included a measure of parenting difficulties as a covariate to rule out the operation of this predictor in affecting children’s internal representations of family relationships.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 243 families (mother, intimate partner, and preschool child) residing in a moderate-sized metropolitan area in the Northeast. To obtain a sample from diverse demographic backgrounds, participants were recruited through local preschools, Head Start agencies, Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) programs, and public and private daycare serving children and families from a variety of demographic backgrounds. The longitudinal design consisted of two annual measurement occasions, with a retention rate of 97%. At Wave 1, the average age of child participants was 4.60 years (SD = .44), and girls comprised around half (56%) of the sample. The sample was racially diverse as almost half of the families were Black or African American (48%), followed by smaller percentages of families who identified as White (43%), multi-racial (6%), or another race (3%). Approximately 16% of family members were Latino. Median household income of families was $36,000 per year (range = $2,000 – $121,000), with most families (69%) receiving public assistance. Median education for parents consisted of a GED or high school diploma. At Wave 1, parents had lived together an average of 3.36 years and had, on average, daily contact with each other and the child (range = daily to 2 or 3 days a week). Ninety-nine percent of mothers and 74% of their partners were the biological parents of the target child, and 47% of the adults were married. Families lost to attrition at Wave 2 did not differ from retained families on any of the study variables at Wave 1.

Procedures

Parents and children visited our research center laboratory for two waves of data collection spaced 1 year apart. All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board prior to conducting the study. Families and teachers were compensated monetarily for their participation.

Interparental Problem Solving Task

At Wave 1, mothers and their partners participated in a 10-minute interparental discussion of common, problematic disagreements in their relationship (Gordis et al., 2001; Grych, 2002). While the child was in a separate room, parents selected problematic issues they felt comfortable discussing in front of their child during the task. After they selected the disagreement topics, an experimenter brought the child into the room and introduced them to a set of toys. The parents then began their conflictual discussion once the experimenter left the room. The task was video recorded for subsequent coding.

Interparental Disagreement Interview

During Wave 1, mothers also participated in the Interparental Disagreement Interview (IDI), administered to them by a trained experimenter. The IDI is a semi-structured narrative interview designed to generate maternal narratives on the causes, nature, and course of interparental conflicts through a series of queries and probes (Davies, Sturge-Apple, Cicchetti, Manning, & Vonhold, 2012; Hentges, Davies, & Cicchetti, 2015). Interviews were video recorded for subsequent coding.

MacArthur Story Stem Battery

At Wave 1, children completed a revised version of the MacArthur Story Stem Battery (MSSB-R; Cummings et al., 2008). The MSSB-R consists of a series of story stems indexing conflicts and adversity in each of three family relationship subsystems: (a) mother-father (i.e., two stories: angry parental conflicts over losing car keys and getting home later than expected), (b) mother-child (i.e., two stories: reunion following extensive separation, child injury after violating maternal instructions), and (c) father-child (i.e., two stories: reunion following extensive separation, child injury after violating paternal instructions). In depicting the story stems, experimenters used animated voices, various toy props, and action figures depicting family members. After each story stem, children completed the stories with the action figures, props, and experimenter probes. Consistent with past research (e.g., Sturge-Apple et al., 2008), the procedure was video recorded for later coding of children’s representations.

Parent and Teacher Questionnaires

At Wave 1, mothers and their partners completed questionnaires assessing interparental conflict, parenting behaviors, family characteristics, and sociodemographic information. At both waves of data collection, children’s preschool and kindergarten teachers completed survey measures of children’s adjustment.

Measures

Interparental conflict

Three measures were used as indicators of a Wave 1 latent construct of interparental conflict. For the first composite indicator of interparental conflict, trained raters assessed each parent (i.e., mother and partner) for specific behaviors during the conflict task on 9-point continuous scales ranging from 1 (Not at all characteristic) to 9 (Highly characteristic). Adapted from the System of Coding Interactions in Dyads (SCID; Malik & Lindahl, 2004), the specific scales included Anger, Aggression, and Controlling Behavior. The Anger scale assesses the extent to which each partner displays signs of tension, frustration, irritation, or anger. The Aggression scale assesses the extent to which each partner uses harmful verbalizations or behavioral displays (e.g., contemptuous, disgusted, mocking, spiteful, hostile, cruel, or condescending) toward the partner. The Controlling Behavior scale assesses the extent to which each partner complains, protests, or uses other coercive, controlling, or aversive behaviors. Each partner received one overall rating on each of the three scales, and two trained coders independently rated 20% of the videos to assess interrater reliability. Intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from .70 to .86. The six scale scores were aggregated to create an observational indicator of interparental conflict for the analyses (α = .77).

As the second indicator of destructive interparental conflict, mothers completed the five Conflict and Problem-Solving Scales (CPS; Kerig, 1996), including: (a) Stonewalling: impasses in conflict characterized by unresolved hostility, distress, and disengagement (14 items; e.g., “Storm out of the house”), (b) Verbal Aggression: use of verbally hostile conflict tactics (16 items; e.g., “Raise voice, yell, shout”), (c) Physical Aggression: use of physical violence in interparental conflict (18 items; e.g., “Push, pull, shove, grab, handle partner roughly”), (d) Avoidance: attempts to ignore or escape arguments (16 items; e.g., “give in to partner’s viewpoint to escape argument”), and (e) Collaboration: use of reasoning, problem-solving, and cooperation (16 items; e.g., “try to find a solution that meets both needs equally”). In support of its validity, prior research has identified the CPS as a correlate of well-established measures of interparental conflict and child maladjustment (Fosco & Grych, 2013; Hentges et al., 2015; Kerig, 1996). Internal consistencies for the scales ranged from .89 to .93. The five measures were standardized and aggregated to form a single composite of maternal reported destructive conflict after reverse scoring the Collaboration scale (α = .82).

For the third indicator, trained raters assessed the videotaped Interparental Disagreement Interviews completed with the mother for specific conflict behaviors of both mother and partner on two scales ranging from 0 (none) to 6 (high). Whereas the Anger scale assesses tension, frustration, irritation, or anger displayed by each partner, the Aggression scale assesses the level of hostility and aggression directed toward the other partner. Two raters overlapped on 20% of the videos to assess interrater reliability (ICCs range from .80–.87). Scores on the four scales were summed to form the third and final indicator of interparental conflict (α = .86).

Family instability

At Wave 1, mothers completed the Family Instability Questionnaire to assess family instability (FIQ; Ackerman et al., 1999; Forman & Davies, 2003). The eight-item measure is designed to assess the total number of unstable events experienced by the family in the last year in five primary domains: (1) changes in caregivers, (2) residential mobility, (3) transitions in romantic relationships of the primary caregiver, (4) job loss, and (5) death or serious illness of a close family member. The measure, which consists of the total number of unstable family events, has good psychometric properties (e.g., Ackerman et al., 1999).

Children’s internal representations of insecurity

Two indicators of a latent construct of children’s internal representations of family-level insecurity at Wave 1 were derived from observer ratings of overall insecurity from the MSSB-R stories (MSSB-R; Cummings et al., 2008). The Child Overall Insecurity scale assessed the degree to which the holistic portrayal of family events within either the interparental or parent-child relationship was likely to serve as a source of support or threat in children’s goal of preserving their physical and psychological well-being. Ratings ranged from 1 (negligible insecurity; e.g., relationships are conveyed as supportive sources of security for the child) to 7 (high insecurity; e.g., strong evidence that family relations serve as a long-term, severe threat to children’s security). Intraclass correlation coefficients, based on overlap between two trained raters on 20% of the videos, ranged from .81 to .88 for the six stories. Composites of insecure representations of parent-child and interparental relationships were created by averaging the three ratings of insecurity in the parent-child (α = .69) and three ratings of insecurity in interparental (α = .78) relationship stories.

Children’s school maladjustment

Teacher reports on four scales from the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ; Ablow et al., 1999) were used as indicators of a latent construct of children’s school maladjustment at Waves 1 and 2. First, the Externalizing scale is comprised of the sum of the 29 items assessing defiance, conduct problems, and aggression (“Defiant, talks back to adults”). Second, the Asocial with Peers scale is comprised of six items designed to assess peer disengagement (e.g., “withdraws from peer activities). Third, the Impulsivity scale measures problems attending to directions, instructions, and preschool activities (e.g., nine items; “can’t stay seated when required to do so”). Fourth, the Teacher-Child Conflict scale assesses children’s difficulties getting along with the classroom teacher (five items; e.g., “you and this child always seem to be struggling with each other”). Internal consistencies for the four scales across the two waves ranged from .86 to .95

Covariates

Two demographic covariates, derived from a maternal interview, included (a) children’s sex (1 = girls; 2 = boys) and (b) parental education level, calculated by averaging mother and partner education level on a scale from 1 (none to 7th grade) to 7 (graduate degree). As the third covariate, we assessed parenting difficulties based on maternal and paternal reports on seven scales from the Socialization of Moral Affect – Parent of Preschoolers Form (SOMA-PP; Rosenberg, Tangney, Denham, Leonard, & Widmaier, 1994). After being presented with vignettes of common childrearing situations depicting child failure, transgression, and success experiences, parents indicated how likely they would be to react in ways that reflect different child-rearing approaches (i.e., from 1 = Not at all likely to 5 = Very likely). Example vignettes include “Your child cleans up his/her room without being asked” and “You and your child are shopping, and she/he deliberately hides from you.” Specific parenting responses, which comprise each of the seven scales, included: (a) Conditional Approval (e.g., “say ‘You’re such a good kid when you clean up like this without being asked’”), (b) Love Withdrawal (e.g., “refuse to speak to your child for the rest of the shopping trip”), (c) Power Assertion (e.g., “say ‘If you don’t behave, I’m going to smack you’”), (d) Child-Focused Negative Responses (e.g., “say ‘You’re such a bad son/daughter, I can’t take you anywhere!’”), (e) Child-Focused Positive Responses (e.g., “say ‘You’re such a helpful person. I can always count on you’”), (f) Neglect/Ignoring (e.g., “briefly look into the room, without making any comment”), and (g) Public Humiliation (e.g., “in the check-out line say, ‘Why don’t you tell the clerk how you disobeyed me again today’”). Internal consistencies ranged from .61 to .87. After reverse scoring the Child-Focused Positive Responses scale, the 14 measures were standardized and aggregated together to form a single, parsimonious composite of parenting difficulties (α = .69).

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 provides the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for the variables used in the primary analyses. In support of the measurement models, correlations between manifest indicators of each of the proposed latent constructs were in the expected direction and generally moderate to strong in magnitude: interparental conflict (mean r = .41), children’s internal representations of insecurity in the family (mean r = .57), and children’s Wave 1 and Wave 2 school maladjustment (mean rs = .50 for both time points).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations of the Main Variables

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Child Sex | - | - | - | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Parental Education | 4.62 | 1.14 | .03 | - | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Parenting Difficulties | .03 | 6.83 | −.02 | −.32* | - | |||||||||||||

| 4. Conflict: IPST | 22.63 | 10.0 | −.03 | −.15* | .08 | - | ||||||||||||

| 5. Conflict: IDI | 9.73 | 5.65 | .01 | −.10 | .17* | .32* | - | |||||||||||

| 6. Conflict: CPS | .00 | 3.80 | .06 | −.06 | .22* | .26* | .64* | - | ||||||||||

| 7. Family Instability | 4.31 | 4.09 | .03 | −.31* | .24* | .16* | .19* | .25* | - | |||||||||

| 8. Interparental Reps | 5.50 | 1.03 | .09 | −.33* | .18* | .15* | .14* | .21* | .23* | - | ||||||||

| 9. Parent-Child Reps | 4.58 | 1.12 | .19* | −.41* | .17* | .09 | .16* | .13 | .19* | .57* | - | |||||||

| 10. Externalizing | 6.79 | 9.49 | .03 | −.08 | .23* | .00 | −.03 | .04 | .13 | .08 | −.03 | - | ||||||

| 11. Asocial | 1.53 | 2.33 | −.16* | −.11 | .12 | .12 | .08 | .09 | .05 | .01 | .04 | .33* | - | |||||

| 12. Impulsive | 4.11 | 4.19 | .09 | −.02 | .21* | −.01 | −.03 | .03 | .03 | .13 | .13 | .73* | .20* | - | ||||

| 13. Teacher Conflict | 8.22 | 4.34 | .05 | −.10 | .19* | −.03 | .05 | .13 | .12 | .09 | .06 | .75* | .33* | .63* | - | |||

| Wave 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 14. Externalizing | 7.37 | 10.35 | .00 | −.24* | .25* | −.01 | .10 | .18* | .33* | .25* | .21* | .48* | .18* | .24* | .39* | - | ||

| 15. Asocial | 1.77 | 2.54 | .10 | −.08 | −.02 | −.05 | .09 | .21* | .11 | .09 | .02 | .10 | .28* | .01 | .10 | .31* | - | |

| 16. Impulsive | 5.03 | 4.81 | .15* | −.20* | .16* | .10 | .17* | .19* | .26* | .34* | .31* | .44* | .12 | .45* | .39* | .64* | .16* | - |

| 17. Teacher Conflict | 8.28 | 4.38 | .07 | −.24* | .23* | .05 | .13 | .17* | .30* | .29* | .26* | .39* | .13 | .26* | .34* | .82* | .39* | .65* |

Note. IPST = Interparental Problem Solving Task; IDI = Interparental Disagreement Interview; CPS = Conflict and Problem-Solving Scales; Reps = Representations.

p < .05.

Primary Analyses

To test associations involving the interplay of interparental conflict and family instability, children’s insecure representations of the family, and school adjustment problems, we utilized autoregressive structural equation modeling (SEM) through AMOS 22.0 (Arbuckle, 2013). Full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used to estimate missing data (median of 5.95% for the measures) and retain the full sample for primary analyses (Enders, 2001). To maximize measurement equivalence in latent constructs of school maladjustment from Wave 1 to Wave 2, we specified strong factorial variance constraints on the analyses (Widaman, Ferrer, & Conger, 2010). Therefore, the following constraints were placed on the school adjustment indicators: (a) fixed and free factor loadings are identical over time, (b) factor loadings of each of the indicators of school adjustment problems were constrained to be equal across time, and (c) intercepts of the same indicators were fixed to be invariant across time.

Analyses of mediational paths involving children’s insecure family representations

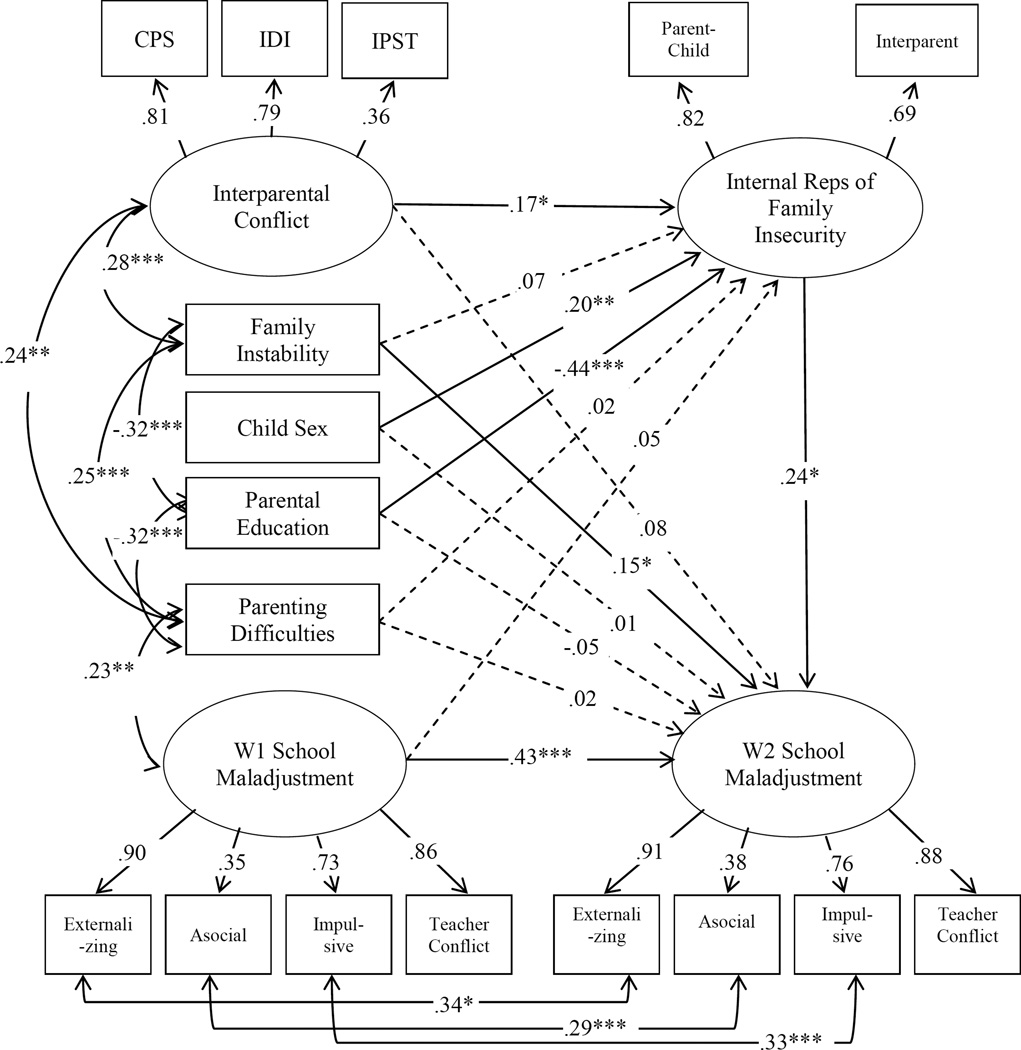

To examine children’s internal representations as mediators of their vulnerability to interparental conflict and family instability, we specified family instability, interparental conflict, Wave 1 preschool adjustment problems, child sex, parent education, and parenting difficulties as predictors of children’s insecure representations of the family and changes in school maladjustment from Wave 1 to Wave 2 (Figure 2). For analysis of the second part of the mediational chain, we simultaneously estimated a predictive path from children’s insecure representations of the family to their Wave 2 school maladjustment. All correlations among exogenous predictors and residual errors on corresponding manifest indicators of adjustment were also estimated. However, for the sake of clarity, only significant associations are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model examining process associations between interparental conflict, family instability, children’s family-level insecurity, and children’s Wave 1 and Wave 2 school maladjustment. Parameter estimates for the structural paths are standardized path coefficients. Dashed lines indicate non-significant pathways. CPS = Conflict and Problem-Solving Scales; IDI = Interparental Disagreement Interview; IPST = Interparental Problem Solving Task; Reps = Representations; W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

The resulting model provided a good fit with the data: χ2 (98, N = 243) = 148.41, p < .001; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .96; χ2/df ratio = 1.51. In support of the latent variable measurements, the fit of the measurement model (i.e., no structural pathways included, only latent variables) was also good: χ2 (62, N = 243) = 100.42, p < .001; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .96; χ2/df ratio = 1.62. As hypothesized, interparental conflict was associated with more insecure internal representations of the family, β = .17, p < .05. Children’s insecure representations, in turn, predicted greater school difficulties at Wave 2 after controlling for maladjustment at Wave 1, β = .24, p < .05. As further evidence of mediation, bootstrapping tests in the PRODCLIN software program indicated that the indirect path involving interparental conflict, child insecurity, and school maladjustment was significantly different from zero, 95% CI [.003, .218] (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). In contrast to the significant mediational pathways for interparental conflict, family instability did not uniquely predict children’s insecure representations of the family, β = .07, p = .35. However, family instability significantly predicted increases in children’s school problems over time, β = .15, p < .05. Child sex and parent education were also associated with children’s insecure representations of the family, β = .20, p < .01 and β = −.44, p < .001, respectively. These findings indicated that boys and children with less educated parents had higher levels of insecure representations. It is also worth noting that although significantly related to insecure representations and maladjustment at both time points at the bivariate level, parenting difficulties were not significantly associated with either insecure representations or Wave 2 school maladjustment in the broader model.

Family instability as a moderator of the mediational role of child insecurity

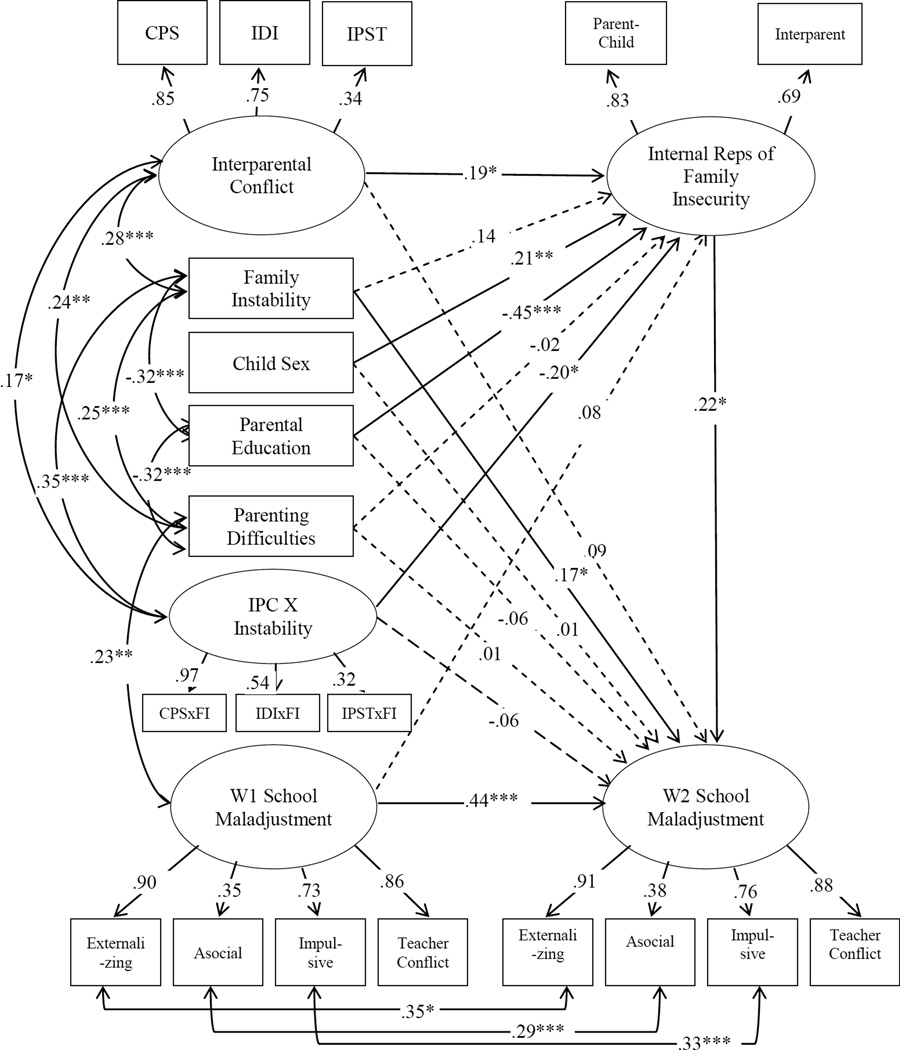

To identify sources of individual differences in the mediational role of children’s insecure representations of the family, our next analytic step was to test family instability as a moderator of interparental conflict, family-level insecurity, and school maladjustment. Following statistical guidelines (Marsh, Wen, and Hau, 2004), we centered all manifest indicator variables and created cross-products by multiplying each indicator of the latent interparental conflict construct by the manifest indicator of family instability. We then specified each resulting product as an indicator of the latent interaction variable. Thus, this latent interaction term was designed to test family instability as a moderator of the first link in the mediational chain involving associations between interparental conflict and children’s internal representations of family insecurity.

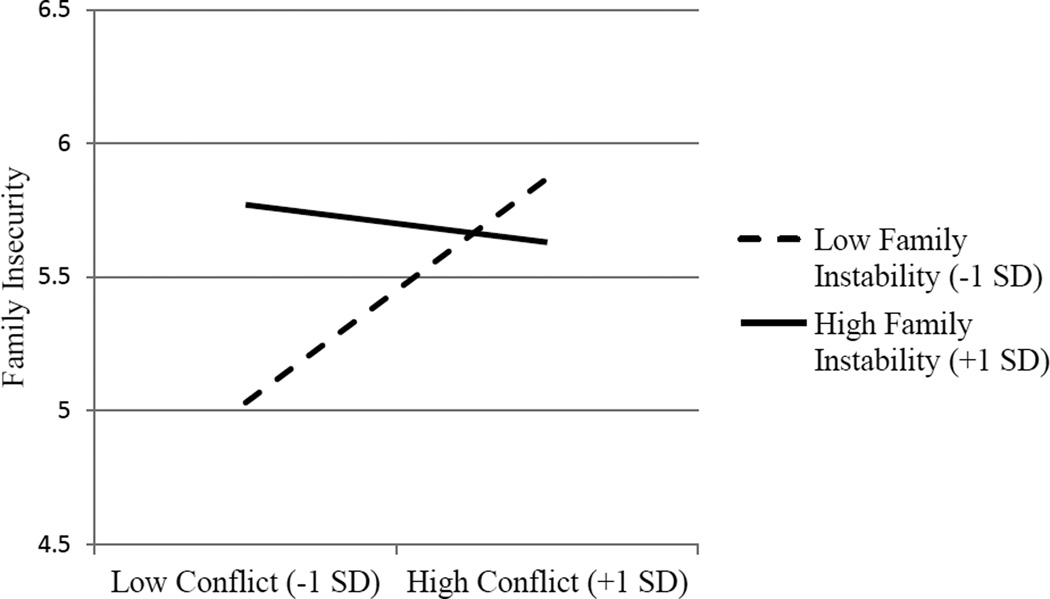

The resulting model, which is depicted in Figure 3, provided a good fit with the data: χ2 (141, N = 243) = 214.76, p < .001, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .94, χ2/df ratio = 1.52. Correlations were also specified among the: (a) predictor, moderator, and covariates and (b) the residual errors of the corresponding manifest indicators of adjustment across the two waves. For the sake of clarity, only significant correlations are depicted in Figure 3. The interaction between family instability and interparental conflict was a significant predictor of child insecurity, even after controlling for parent education, parenting difficulties, children’s sex, and Wave 1 preschool adjustment problems, β = −.20, p < .05. To characterize the interaction, we conducted simple slope plots and analyses at −1 SD and +1 SD from the mean of interparental conflict (Aiken & West, 1991). The resulting graphical plot of the moderating effects presented in Figure 4 revealed a disordinal interaction. Post hoc simple slope analyses designed to further characterize the nature of the interaction indicated that interparental conflict was associated with significantly higher levels of insecure representations for children who experienced lower (−1 SD), b = 0.10, p < .001, but not higher (+1 SD), b = −0.02, p = .55, levels of family instability. Bootstrapping tests in the PRODCLIN software program (MacKinnon et al., 2007) indicated that the indirect path involving interparental conflict, family insecurity, and school maladjustment was significantly different from zero at low (95% CI [.015, .488]) and medium (95% CI [.002, .230]) but not high (95% CI [−.177, .079]) levels of instability.

Figure 3.

Structural equation model examining the interactive effect of family instability and interparental conflict on children’s family-level insecurity, and children’s Wave 1 and Wave 2 school maladjustment. Parameter estimates for the structural paths are standardized path coefficients. Dashed lines indicate non-significant pathways. CPS = Conflict and Problem-Solving Scales; IDI = Interparental Disagreement Interview; IPST = Interparental Problem Solving Task; Reps = Representations; FI = Family Instability; IPC = Interparental Conflict; W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Figure 4.

A graphical plot of the interaction between interparental conflict and family instability in predicting children’s insecure internal representations of the family.

To more authoritatively test which pattern of moderation more closely corresponds with the data, statistical guidelines call for calculating regions of significance on X (RoS on X) tests (Aiken & West, 1991; Dearing & Hamilton, 2006). RoS on X tests invert the predictor and moderator to yield analyses of the significance of the association between the moderator and outcome within the bounded regions of the proposed predictor (i.e., + or − 1 SD). Thus, the RoS on X test was used to test whether family instability significantly predicted children’s insecure representations of the family at high and/or low levels of interparental conflict. Consistent with the vulnerable-stable form of risk (Luthar et al., 2000), the results indicated that family instability predicted increases in insecurity at low (−1 SD), but not high (+1 SD) levels of interparental conflict, b = 0.09, p < .01 and b = −0.03, p = .31, respectively.

Discussion

Although EST posits that destructive interparental conflict may increase children’s vulnerability to adjustment problems by undermining their appraisals of the broader family unit to serve as a source of security (Davies & Cummings, 1994), empirical tests of this hypothesis are rare. Even less is known about how the mediational role of children’s insecurity in the family may vary as a function of the broader family climate. Thus, this multi-method, multi-informant, longitudinal study examined how the interplay between children’s experiences with destructive interparental conflict and unstable family events informs an understanding of their insecure representations of family relationships and changes in school adjustment problems over time. Findings indicated that higher levels of destructive interparental conflict were associated with children’s insecure internal representations of the family, which, in turn, predicted increases in their school problems over a 1-year period. In addition, unstable family events moderated the association between interparental conflict and children’s insecurity in the family unit.

Findings from mediational tests indicated that children’s insecure representations of the family mediated the association between destructive interparental conflict and increases in children’s school problems. These results are consistent with the notion that destructive interparental conflict may amplify children’s concerns about their safety in multiple family contexts that expand beyond the interparental relationship to include the parent-child subsystems. According to EST (Cummings & Davies, 2010), children who are exposed to destructive interparental conflict have sound reasons for being concerned about their safety in multiple family contexts. Conflict between parents may undermine security by increasing the likelihood that unresolved hostility from conflicts will proliferate into parent-child and broader family interactions. Likewise, arguments between parents are commonly manifestations of underlying power struggles and, as a result, may lead to collapses, perturbations, and dissolution in the social hierarchy of the family unit (Johnston et al., 2009). As reflections of these concerns, children’s insecure representations of the family are proposed to increase their vulnerability to psychological problems by sensitizing them to potential adversity in novel and challenging contexts (Repetti, Robles, & Reynolds, 2011). Relying on old defensive ways of processing and interpreting the meaning of novel interpersonal events in the school setting may specifically increase children’s prioritization of personal safety goals at the cost of investing in the mastery of the physical and social environment (Davies et al., 2006). Accordingly, children’s prolonged concerns about safety in the family may be manifested in school adjustment difficulties by virtue of the developmental challenges of forming new close relationships, navigating their positions with peer and classroom hierarchies, learning and conforming to new guidelines of behavioral conduct, and actively participating in academic activities (Ladd et al., 1999).

Consistent with previous research (Cavanagh & Huston, 2008; Milan, Pinderhughes, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2006), family instability uniquely predicted increases in school adjustment problems from Wave 1 to Wave 2 even with the inclusion of interparental conflict, demographic characteristics, parenting difficulties, children’s representations, and prior school problems as predictors. However, although associations between family instability and the two dimensions of insecure family representations were significant in bivariate analyses (see Table 1), family instability was not a significant predictor of children’s insecure representations in the broader multivariate model involving destructive interparental conflict and the covariates. Given that interparental conflict and parenting dimensions were moderately correlated with family instability, it is possible that family instability may indirectly increase children’s insecure representations through its association with instability and discord in the interparental relationship (Bachman et al., 2011; Davies & Cummings, 1994). Likewise, family instability may be part of a broader constellation of disadvantageous socioeconomic (e.g., family income, parent education) indices that alter children’s ways of appraising and interpreting family events. In accord with this explanation, SEM results indicated that lower levels of parent education were associated with higher levels of family instability and insecure representations of the family. Family instability may also be linked to school maladjustment through other mediators that warrant further investigation. For instance, past research has suggested that family instability may impact child maladjustment through the development of callous interpersonal orientations (Ackerman et al., 1999) or disruptions in stress-sensitive physiological systems (e.g., HPA system; Susman, 2006).

Although family instability was unrelated to children’s insecurity in the broader multivariate model, our findings did reveal that it moderated the relationship between interparental conflict and insecure representations. Follow up analyses of the interaction provided support for the moderating effect as assuming a vulnerable-stable (Figure 1a) rather than vulnerable-reactive (Figure 1b) form (see Luthar et al., 2000). Interestingly, the combination of destructive interparental conflict and family instability did not incrementally increase children’s disadvantage above and beyond either form of family risk considered singly. Therefore, children’s concerns about security in the family were uniformly high under conditions of heightened family instability across levels of exposure to interparental conflict. This vulnerable-stable pattern of risk is consistent with the stress-sensitization model in the developmental psychopathology literature (Rudolph & Flynn, 2007). In highlighting conditions underlying sensitization, exposure to adverse experiences may reduce children’s threshold for developing coping difficulties when exposed to other forms of stress. Thus, children who experience higher levels of family instability would require only mild exposure to interparental conflict to trigger insecurity, whereas children from more stable homes would require exposure to more intense conflict to elicit the same degree of insecurity and, in turn, school problems.

As a complementary framework, the risk saturation model offers a distinct set of interpretations for the vulnerable-stable pattern of findings (Morris, Ciesla, & Garber, 2010). According to conceptualizations that fall within this framework, children’s reactivity to family stress may reach an asymptote when under high (i.e., intense or multiple) risk conditions (e.g., Davies & Sturge-Apple, 2007). At a psychological level of analysis, this may be evidenced by children actively disengaging from the family in contexts where difficulties between parents (i.e., interparental conflict) or in the broader family (i.e., instability) is high. Thus, as exposure to a specific form of family stress increases, children may progressively refrain from processing other family threats to guard against experiencing overwhelming levels of distress. At a physiological level of analysis, there is also some evidence for blunting of stress-responsive neurobiological systems following exposure to high or chronic risk conditions (Trickett, Noll, Susman, Shenk, & Putnam, 2010). Thus, it is possible that the dampening of physiological systems in the wake of prolonged or intense exposure to adverse socialization conditions may serve an adaptive function of thwarting the negative impact of elevated physiological reactivity on brain, cardiovascular, and immune system functioning (Susman, 2006; Gold & Chrousos, 2002).

As an alternative explanation for our findings, the attenuation hypothesis proposes that high conflict and instability in homes may blunt children’s ability to interpret and comprehend the meaning of other family processes (Susman, 2006). More specifically, the chaotic, unpredictable, and frightening characteristics of interparental conflict and family instability may disrupt the capacity for brain regions (e.g., limbic system) to process information on the emotional and relational consequences of family events. Thus, under conditions of high family instability, attenuation may be signified by children’s diminished attunement to interparental conflict or, more specifically, a lack of correspondence between actual exposure to destructive conflict and insecure representations of the family unit. In accord with these hypotheses, our results showed that the association between interparental conflict and insecure representations progressively diminished as children’s exposure to family instability increased. In a complementary fashion, attenuation under conditions of high interparental conflict may also be reflected in diminished or null associations between exposure to family instability and children’s insecure representations. In support of this prediction, the significant relationship between children’s exposure to family instability and their insecure family representations was significant in contexts of low, but not high, interparental conflict.

Results of the study must also be interpreted in the context of study limitations. First, caution should be exercised in generalizing the findings to other samples. Although the families in our study were relatively diverse in their racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, the results may not replicate with families facing other conditions (e.g., high adversity or resource-rich). It is also unclear whether the findings would apply for children in developmental periods outside of the early school years. Second, our focus on examining children’s insecurity in the family through assessments of their internal representations was guided by theory, but there are a number of other mechanisms (e.g., negative affect, appraisals of blame, involvement) that may also inform our understanding of the pathways of risk experienced by children from high conflict homes (Grych & Fincham, 1990; Jouriles, Rosenfield, McDonald, & Mueller, 2014). Third, family instability may be part of a larger constellation of family and child factors that also alter the mediational pathways of children’s insecurity in the family. Fourth, although our focus was on understanding the interplay between interparental conflict and family instability, it is also important to expand multivariate models to include other family dimensions (e.g., parenting processes). Fifth, the modest effect size of the interaction underscores that there is wide variability in how children interpret family events following similar experiences with family instability and interparental conflict. For example, additional contextual factors (e.g., culture, race, ethnicity) may underlie variability in the moderating effects of family instability (e.g., McLoyd, Harper, & Copeland, 2001). Sixth, although we utilized a multi-method approach to assessing interparental conflict, additional increases in rigor might be achieved by including more informants (e.g., fathers). Finally, although our longitudinal prediction of changes in children’s school problems provided relatively rigorous tests of the hypotheses, our study does not permit a full prospective analysis of change at each link in the mediational chain (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Therefore, it is possible that the concurrent associations between inteparental conflict and children’s family representations may reflect a bidirectional interplay between interparental and child problems.

In summary, our multi-method, multi-informant, longitudinal study was designed to examine how the interplay between children’s experiences with destructive interparental conflict and unstable family events informs an understanding of their insecure representations of family relationships and school adjustment problems. In expanding beyond the predominant focus on assessing insecurity in the interparental relationship, findings from our study identified children’s insecure representations of the broader family unit as a mediator in the prospective pathway between their exposure to destructive interparental conflict and their increases in school problems over time. Family instability further served as a moderator in the mediational link between interparental conflict and children’s insecure family representations. In highlighting the operation of a vulnerable-stable form of moderation, interparental conflict was a significant predictor of children’s insecure representations only for children who experienced low levels of instability in the family unit. Likewise, links between family instability and insecure representations were only evident for children who witnessed low levels of interparental conflict. Thus, the findings highlight that exposure to either interparental conflict or family instability is sufficient to increase children’s concerns of security even in the absence of the other form of risk. Although replication and extension of our findings is necessary before we can offer definitive clinical recommendations, the results highlight the possibility that interventions that specifically focus on either improving interparental relations or reducing instability may not be particularly effective in reducing children’s concerns about their security and, in turn, their school adjustment problems. Therefore, maximizing the efficacy of family intervention programs may require more comprehensive, multi-faceted clinical targets and tools that are designed to increase both interparental relationship quality and family stability.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Eunice Shriver Kennedy National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD065425) awarded to Patrick T. Davies and Melissa L. Sturge-Apple. The authors are grateful to the children, parents, teachers, and community agencies who participated in this project. We would also like to thank the Mt. Hope Family Center Staff and the graduate and undergraduate students at the University of Rochester who assisted on this project.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Jesse L. Coe declares that she has no conflict of interest. Patrick T. Davies declares that he has no conflict of interest. Melissa L. Sturge-Apple declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Ethical Approval: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study.

References

- Ablow J, Measelle JR, Kraemer HC, Harrington R, Luby J, Smider N, Kupfer DJ. The MacArthur Three-City Outcome Study: Evaluating multi-informant measures of young children’s symptomatology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1580–1590. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman BP, Kogos J, Youngstrom E, Schoff K, Izard C. Family instability and the problem behaviors of children from economically disadvantaged families. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:258–268. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. IBM SPSS AMOS 22 User’s Guide. Spring House, PA: Amos Development Corp.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub CC, O’Connor E, Rappolt-Schlichtmann G, Fischer KW, Rogosch FA, Toth SL, et al. Cognitive and emotional differences in young maltreated children: A translational application of dynamic skill theory. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:679–706. doi: 10.1017/s0954579406060342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman H, Coley RL, Carrano J. Maternal relationship instability influences on children’s emotional and behavioral functioning in low-income families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:1149–1161. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Attachment theory: Retrospect and prospect. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50:3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE, Huston AC. The timing of family instability and children’s social development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1258–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Effects of marital conflict on children: recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:31–63. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Koss KJ, Davies PT. Prospective relations between family conflict and adolescent maladjustment: Security in the family system as an explanatory mechanism. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015;43:503–515. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9926-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Schermerhorn AC, Keller PS, Davies PT. Parental depressive symptoms, children’s representations of family relationships, and child adjustment. Social Development. 2008;17:278–305. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey M, Cummings EM. Children’s emotional security and interparental conflict. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67:1–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML. Advances in the formulation of emotional security theory: An ethologically-based perspective. Advances in Child Behavior and Development. 2007;35:87–137. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-009735-7.50008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Cicchetti D, Manning LG, Vonhold SE. Pathways and processes of risk in associations among maternal antisocial personality symptoms, interparental aggression, and preschooler's psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:807–832. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Winter MA, Cicchetti D. The implications of emotional security theory for understanding and treating childhood psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:707–735. doi: 10.1017/s0954579406060354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, Hamilton LC. Contemporary advances and classic advice for analyzing mediating and moderating variables. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71:88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. A primer on maximum likelihood algorithms available for use with missing data. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:128–141. [Google Scholar]

- Forman EM, Davies PT. Family instability and young adolescent maladjustment: The mediating effects of parenting quality and adolescent appraisals of family security. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:94–105. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman EM, Davies PT. Assessing children’s appraisals of security in the family system: The development of the Security in the Family System (SIFS) scales. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:900–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Grych JH. Capturing the family context of emotion regulation: A family systems model comparison approach. Family Studies. 2013;34:557–578. [Google Scholar]

- Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in melancholic and atypical depression: high vs low CRH/NE states. Molecular Psychiatry. 2002;7:254–275. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordis EB, Margolin G, John RS. Parents’ hostility in dyadic marital and triadic family settings and children’s behavior problems. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:727–734. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH. Children’s appraisals of interparental conflict: Situational and contextual influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:437–453. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH. Marital relationships and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 4: Social conditions and applied parenting. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2002. pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive- contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;111:434–454. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentges RF, Davies PT, Cicchetti D. Temperament and interparental conflict: The role of negative emotionality in predicting child behavioral problems. Child Development. 2015;86:1333–1350. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J, Roseby V, Kuehnle K. In the name of the child: A developmental approach to understanding and helping children of conflict and violent divorce. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Rosenfield D, McDonald R, Mueller V. Child involvement in interparental conflict and child adjustment problems: A longitudinal study of violent families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:693–704. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9821-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Spiller L, Stephens N, McDonald R, Swank P. Variability in adjustment of children of battered women: The role of child appraisals of interparent conflict. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK. Assessing the links between interparental conflict and child adjustment: The conflicts and problem-solving scales. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:454–473. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Birch SH, Buhs ES. Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development. 1999;70:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik NM, Lindahl KM. System for coding interactions in dyads (SCID) In: Kerig PK, Baucom DH, editors. Couple Observational Coding Systems. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 2004. pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Wen Z, Hau KT. Structural equation models of latent interactions: Evaluation of alternative estimation strategies and indicator construction. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:275–300. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Harper CI, Copeland NL. Ethnic minority status, interparental conflict, and child adjustment. In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and application. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 98–125. [Google Scholar]

- Milan S, Pinderhughes EE the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Family instability and child maladjustment trajectories during elementary school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:43–56. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Ciesla JA, Garber J. A prospective study of stress autonomy versus stress sensitization in adolescents at varied risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:341–354. doi: 10.1037/a0019036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim D. Child, parent, and parent-child emotion narratives: Implications for developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;2006:771–790. doi: 10.1017/s095457940606038x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Robles TF, Reynolds B. Allostatic processes in the family. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:921–938. doi: 10.1017/S095457941100040X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg KL, Tangney JP, Denham S, Leonard AM, Widmaier N. Socialization of moral affect – parent of preschoolers form (SOMA-PP) Fairfax, VA: George Mason University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M. Childhood adversity and youth depression: Influence of gender and pubertal status. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:497–521. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Winter MA, Cummings EM, Schermerhorn A. Interparental conflict and children’s school adjustment: The explanatory role of children’s internal representations of interparental and parent-child relationships. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1678–1690. doi: 10.1037/a0013857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susman EJ. Psychobiology of persistent antisocial behavior: Stress, early vulnerabilities, and the attenuation hypothesis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2006;30:376–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D, Rogosch F, Sturge-Apple ML. Maternal depression, children’s attachment security, and representational development: An organizational perspective. Child Development. 2009;80:192–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Noll JG, Susman EJ, Shenk CE, Putnam FW. Attenuation of cortisol across development for victims of sexual abuse. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:165–175. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, Ferrer E, Conger RD. Factorial invariance within longitudinal structural equation models: Measuring the same construct across time. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4:10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]