Abstract

Background

Observational studies suggest that insomnia might be associated with an increased risk of depression with inconsistent results. This study aimed at conducting a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies to evaluate the association between insomnia and the risk of depression.

Methods

Relevant cohort studies were comprehensively searched from the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases (up to October 2014) and from the reference lists of retrieved articles. A random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled risk estimates and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). The I 2 statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity and potential sources of heterogeneity were assessed with meta-regression. The potential publication bias was explored by using funnel plots, Egger’s test, and Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill methods.

Results

Thirty-four cohort studies involving 172,077 participants were included in this meta-analysis with an average follow-up period of 60.4 months (ranging from 3.5 to 408). Statistical analysis suggested a positive relationship between insomnia and depression, the pooled RR was 2.27 (95 % CI: 1.89–2.71), and a high heterogeneity was observed (I 2 = 92.6 %, P < 0.001). Visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed some asymmetry. The Egger’s test identified evidence of substantial publication bias (P <0.05), but correction for this bias using trim-and-fill method did not alter the combined risk estimates.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis indicates that insomnia is significantly associated with an increased risk of depression, which has implications for the prevention of depression in non-depressed individuals with insomnia symptoms.

Keywords: Insomnia, Sleep disorders, Depression, Meta-analysis, Epidemiology

Background

Depression is a common mental disorder and is described as a continuum ranging from a few depressive symptoms to major depression [1]. It is one of the leading global burdens of disease (GBD) and is estimated to be one of the top three health concerns by 2020 [2, 3]. Some evidence showed that 5.8 % of men and 9.5 % of women would experience a depressive episode in any given year for a lifetime [4]. Among older adults in Japan, depression is one of the most common diseases and is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality [5, 6].

Insomnia is the subjective feeling of having difficulties initiating or maintaining sleep (DIS and DMS respectively, jointly referred to as DIMS) or of non-restorative sleep (NRS) [7, 8]. Epidemiological studies have shown that 20 to 35 % of the general population report insomnia symptoms, and that 10 to 20 % have clinically significant insomnia syndrome [9–13]. Insomnia prevalence has been found to be associated with measurements of worse physical and mental health [14].

Both insomnia and depression are major public health problems. It has been reported that insomnia is associated with an increased risk of depression and/or anxiety disorders [9, 15]. The identification of modifiable risk factors for depression has a greatly important implication for the primary prevention. Many observational studies have focused on whether insomnia has an influence on depression risk [9, 16–23]. In 2011, Baglioni et al. [24] performed a meta-analysis to investigate the association between insomnia and the risk of depression, and the results showed that an overall odds ratio (OR) for insomnia to predict depression of 2.60 (95 % confidence interval (CI):1.98–3.42). Since then, many new observational studies have emerged, and some of them had large sample sizes and long follow-up lengths. In addition, the previous review only conducted a subgroup analysis by different age groups of participants. The incidences and the risk factors for depression might vary with the definitions of depression and the exposure changes, or vary in samples from different gender, follow-up durations, and geographic regions. Including more studies and enlarging the sample size would be important for strengthening the reliability of describing the association between insomnia and depression risk. Therefore, we conducted an updated-analysis to further investigate the issue.

Methods

Search strategy

This meta-analysis was performed according to the checklist of the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines [25]. The systematic literature search was conducted by two investigators (L.Q.L. and C.M.W.) independently through the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases for pertinent studies published in English and Chinese from their inception to October 2014. The key words used as the search terms were the following: “insomnia”, “sleep disorder”, “sleep disturbance”, “sleep problem”, “sleep quality”,”sleep duration” in combination with “depression”, “mental disorder”, and “anxiety”. The search was restricted to studies in humans. In addition, the reference lists of all identified relevant publications were reviewed.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

The eligibility of each study was assessed independently by two investigators (L.Q.L. and C.M.W.), and disagreements were resolved through consultation with the third investigator (Z.X.L.). Studies meeting the following criteria were included in the meta-analysis: (1) the main exposure of interest was insomnia and the outcome of interest was depression; (2) the study design was prospective cohort; (3) insomnia was characterized by DIS and/or DMS or NRS; (4) depression was measured by self-reported symptom scales, physician/clinician diagnosis, or structured clinical diagnostic interview [24]; and (5) the study reported a ratio-based measurement of association of insomnia with depression.

Studies were excluded if: (1) the study was not published as the full reports, such as case reports, commentaries, conference abstracts and letters to editors; (2) the study had a retrospective design; (3) participants with depression at baseline were not excluded for the analysis or the effect of symptoms of insomnia on predicting depression was not controlled for other depressive symptoms at baseline [24]; and (4) Both insomnia and depression acted as the exposure resulting in predicting the other disorder (such as anxiety). If duplicate publications from the same study were identified, we would include the result with the largest number of individuals from the study.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted for each study: name of the first author, publication year, study name, source of the participants, geographic region, gender, mean age of the participants at baseline, insomnia measurement, definition of insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR criteria [8], depression measurement, length of the follow-up period, number of the follow-up assessments, sample size, the OR, relative risk (RR) or hazard ratio (HR) with 95 % CI, and covariates that were adjusted in the multivariable analysis.

Quality assessment

Two investigators (C.M.W. and Y.G.) independently fulfilled the quality assessment using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [26], which is a validated scale for non-randomized studies in meta-analysis. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale is a nine-point scale that allocates points on the basis of the process of selection of the cohort study and measurement of exposure (0–4 points), the comparability of cohorts (0–2 points) and the identification of the outcome and adequacy of follow-up (0–3 points). We assigned scores of 0–3, 4–6, and 7–9 for the low, moderate, and high quality of studies, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The RR was considered as the common measure of the association between insomnia and depression. The HR was considered to be equivalent to RR, and the OR was transformed into the RR. OR was corrected according to the following formula: [27]. In the cohort study, P 0 indicated the incidence of the outcome of interest in the non-exposed group. We preferentially pooled multivariable adjusted risk estimates where such estimates were reported. Where adjusted analysis was not available, we pooled the unadjusted estimates. The RRs for the associations between insomnia and the risks of depression were pooled using the fixed-effects model where heterogeneity was not detected, or the random-effects model was used otherwise.

For further confirmation and assessment of the association between insomnia and the risk of depression, subgroup analysis was carried out to explore the sources of potential heterogeneity and examine the robustness of the primary results. The differences among subgroups were tested by meta-regression analysis (using STATA ‘metareg’ command). In sensitivity analysis, we conducted a leave-one-out analysis [28] to observe the magnitude of influence of each study on the pooled RR.

Statistical heterogeneity among studies was evaluated with the Q and I 2 statistics. For the Q statistic, statistical significance was set at P < 0.1 and for the I 2, the values of 25 %, 50 % and 75 % respectively denoted cut-off points for low, moderate and high degrees of heterogeneity [29]. Potential publication bias was evaluated with a funnel plot and the Egger’s test [30]. The Duval and Tweedie nonparametric trim-and-fill methods [31] were performed to further assess the potential publication bias. All statistical analyses were performed with STATA statistical software (version 12.0; College Station, TX, USA). All reported probabilities (P values) were two-sided, with a significance level of 0.05 except where otherwise specified.

Results

Literature search

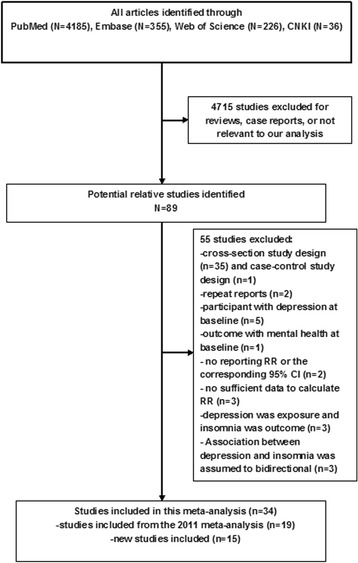

Figure 1 presents the process of this study selection. The search strategy identified 4,802 articles, in which 4,185 articles from the PubMed, 355 articles from the Embase, 226 from the Web of Science, and 36 from the CNKI were retrieved. Of these, based on abstracts or titles, the majorities were excluded after the first screening because they were reviews, case reports, or not relevant to our analysis. After full-text review of the remaining 89 studies, 55 studies were excluded for the reasons shown in Fig. 1. Of note, all of the 21 studies included in the previous review were eligible according to the criteria in our research except two duplicated studies [7, 16] used the same samples as the other two studies [20, 32], and articles with longest follow-up and more detailed information were retained. Thus, 34 eligible cohort studies were finally included in this meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection of insomnia in relation to depression

Characteristics of studies

The included 34 studies [9, 10, 17–23, 32–56] were published between 1989 [9] and 2014 [32, 55, 56], and characteristics of them are shown in Table 1. The sample sizes of the cohorts ranged from 147 [40] to 44,270 [56] with a total of 172,077. The length of follow-up duration ranged from 3.5 [32] to 408 [18] months in this study, with an average of 60.4 months. Fourteen studies were conducted in the United States [9, 10, 17–19, 22, 23, 34–36, 38, 40, 51, 52] and in Europe [20, 32, 33, 37, 39, 41, 42, 45–47, 49, 50, 52, 53, 56] respectively, two studies in Australia [44, 55], and four studies in Asia [21, 43, 48, 54]. Three studies reported results for males only [18, 44, 52], and three studies reported results for females only [32, 46, 55], 27 studies reported results for both males and females [9, 10, 17, 19–23, 33–43, 45, 47–51, 53, 54, 56],and one study [47] reported results for males and females separately. In the present study, 11 studies [9, 10, 19–21, 32–34, 36, 38, 42, 46, 48, 52, 56] diagnosed insomnia on the basis of all DSM- IV criteria [57]: sleep difficulties, duration and daytime consequence (sd, dur and day), 10 studies [10, 23, 33, 34, 36, 47, 50, 51, 53, 54] based the diagnosis only on sleep difficulties and duration criteria (sd and dur), and 13 studies [17, 18, 22, 35, 37, 39, 40, 43–45, 49, 55] took into consideration only the sleep difficulties criterion (sd) [24]. Ten studies [18–20, 32, 45, 50, 51, 54, 55, 58] assessed insomnia repeatedly during the course of the follow-up, and the rest of the studies assessed insomnia at baseline. Interobserver agreement (κ) between two investigators was 0.98. The results of quality assessment are shown in Table 2. The average score for the quality assessment of included cohort studies was 6.6 (of a possible 9 points), which indicated that the quality for all studies was moderate-high in a whole.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies in the meta-analysis

| Study source | Study name | Sex | Insomnia measurement | DSM-IV-TR insomnia criteria satisfied | Depression measurement | Follow-up time (months) | Number of follow-up assessments | Baseline age (years) | No of participants | Covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ford and Kamerow, 1989, USA [9] | National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study | M/F | Diagnostic Interview Schedule | sd§, dur† and day | Diagnostic Interview Schedule | 12 | 1 | Range 18+; mean 45.79 |

7,954 | Age, sex, socioeconomic status, race, and marital status |

| Brabbins et al., 1993, UK [33] | None | M/F | Geriatric Mental State | sd and dur | Geriatric Mental State | 36 | 1 | Range 65+; mean 69.76 | 701 | No covariate adjustment |

| Breslau et al., 1996, USA [34] | None | M/F | NIHM Diagnostic Interview Schedule | sd and dur | NIHM Diagnostic Interview Schedule | 42 | 1 | Range 21–30; mean 26.14 | 979 | Sex, hypersomnia, and number of other depressive symptoms |

| Chang et al. 1997 USA [18] | Johns Hopkins Precursors Study | M | Habit Survey Questionnaire | sd | Checklists medical reports and self-reports | 408 | 7 | Range NA; mean 26.3 | 941 | Age at graduation, class year, parental history of clinical depression, coffee consumption, and measures of temperament |

| Weissman et al. 1997 USA [10] | National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study (ECA) | M/F | Questionnaires | sd and dur | Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) | 12 | 1 | Range 18+; mean 48.23 | 7,113 | Age, sex, and site |

| Foley et al. 1999 USA [35] | None | M/F | Interview | sd | CES-D | 36 | 3 | Range 65+; mean 80.09 | 6,899 | No covariate adjustment |

| Johnson et al. 2000 USA [36] | None | M/F | 1 item from the CBCL | sd and dur | CBCL and TRF | 60 | 1 | Range NA; mean 6 | 717 | Sex, birth weight, and mother’s history of MDD using generalized estimation equations |

| Mallon et al. 2000 Sweden [37] | County of Dalarna registry | M/F | Uppsala Sleep Inventory | sd | HADS | 144 | 1 | Range 45–65; mean 55 | 1,244 | Smoking, depression, and insomnia |

| Roberts et al. 2000 USA [17] | Alameda Country study | M/F | 2 Items from the DSM-12D | sd | 12 Items from the DSM-12D | 12 | 1 | Range 50+; mean 64.9 | 2,370 | Age, sex, marital status, social isolation, education, financial problems, problems with daily activities, and heave drinking |

| Roberts et al. 2002 USA [38] | None | M/F | Questionnaires | sd, dur and day | Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children | 12 | 1 | Range 11–17; mean 15 | 3,136 | Age, values of the functioning measures at baseline, sex, parental education, and insomnia level |

| Hein et al. 2003 Germany [39] | None | M/F | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | sd | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | 60 | 1 | Range 55+; mean 60 | 664 | No covariate adjustment |

| Perlis et al. 2006 USA [40] | None | M/F | HAMD (sleep items) | sd | SCID and HAMD | 12 | 1 | Range 60+; mean 72 | 147 | No covariate adjustment |

| Morphy et al. 2007 UK [41] | None | M/F | Jenkins Sleep Scale | sd | HADS | 12 | 1 | Range 18+; mean 50 | 1,589 | Age, sex, social class, anxiety (except when anxiety is the problem of interest), depression (except when depression is the problem of interest), and pain areas (except when widespread pain is the problem of interest) |

| Buysse et al. 2008 Switzerland [20] | The Zurich Study | M/F | SPIKE and visual analogue scales | sd, dur and day | SPIKE | 240 | 6 | Range NA; mean 19.5 | 278 | Concurrent MDE at the time of insomnia diagnosis |

| Cho et al. 2008 USA [19] | Depression Substudy | M/F | PSQI | sd, dur and day | SCID and BDI | 24 | 3 | Range 60+; mean 69 | 329 | Group status, depression symptoms, medical disease, age, sex, marital status, and education |

| Jansson-Fröjmark and Lindblom.2008 Sweden [42] | None | M/F | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaires and Uppsala Sleep Inventory | sd, dur and day | HADS | 12 | 1 | Range 20–60; mean 41.3 | 1,489 | Age, sex |

| Roane and Taylor. 2008 USA [23] | National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) | M/F | In-home interview | sd and dur | In-home interview | 78 | 1 | Range 12–18; mean 16 | 3,582 | Sex |

| Kim et al. 2009 Korea [21] | Kwangju community study | M/F | Interview | sd, dur and day | Geriatric Mental State | 24 | 1 | Range 65+; mean 72.2 | 792 | Age, sex, education, housing, past occupation, current employment, living area, life events, social deficit, physical activity, GMS organicity, GMS anxiety, and daily drinking. |

| Szklo-Coxe et al. 2010 USA [22] | Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study | M/F | PSG + interview and self-reported symptoms | sd | Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale | 44 | 1 | Range 33–71; mean 53.6 | 555 | Age, sex, chronic health conditions, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, caffeine consumption, use of hypnotic agents, and BMI |

| Yokoyama et al. 2010 Japan [43] | Nihon University Japanese Longitudinal Study of Aging: (NUJLSOA) | M/F | Questionnaire | 11-item short form of the CES-D | 36 | 1 | Range 69+; mean 73.1 | 3,065 | Age, sex, educational history, place of residence, sleep duration, excessive daytime sleepiness, discomfort feeling in the legs, subjective sleep sufficiency, psychological stress, self-rated health, and activities of daily living | |

| Jaussent et al. 2011 France [45] | French Three-City Study | M/F | Questionnaire and clinical interview | sd | CES-D | 48 | 2 | Range 65+; mean ≥ 60 | 3,824 | Age, center, CES-D baseline, sex, education, living alone, coffee consumption, alcohol consumption, smoking, chronic disease, past major depression, disability, prescribed sleep medication intake, and homeopathic and non-prescription treatments for sleep |

| Almeida et al. 2011 Australia [44] | Health In Men Study (HIMS) | M | Questionnaire | sd | Medical records (based on ICD-10) | 72 | 1 | Range 70+; mean ≥ 60 | 5,127 | Age, education group, migrant status, living alone, low social support group, smoking group, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, chronic respiratory diseases, coronary artery disease, stroke, and cancer |

| Marques et al. 2011 Portugal [46] | None | F | Interview | sd, dur and day | DSM-IV | 5 | 1 | Range 18–44; mean 29.8 | 382 | Negative affect, positive affect, and lifetime depression |

| Thomée et al. 2011 Sweden [47] | None | M/F | A single item adapted from the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire | sd and dur | Two items from the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (Prime-MD) | 12 | 1 | Range 20–24; mean < 60 | 1,455 | Relationship status, educational level, and occupation |

| Okajima et al. 2012 Japan [48] | None | M/F | PSQI | sd, dur and day | CES-D | 24 | 1 | Range 20+; mean 57.4 | 1,577 | Age, sex, disease currently treated, habitual alcohol ingestion, smoking habit, and living alone |

| Salo et al. 2012 Finland [49] | Finnish Public Sector Study | M/F | The 4-item Jenkins Sleep Problem Scale | sd | Health register and medical records | 42 | 1 | Range 19–70; mean 43.9 | 40,791 | Age, sex, socioeconomic position, night/shift work, health behaviors, baseline physical health, use of pain killers, psychological distress, and anxiety |

| Skapinakis et al. 2013 UK [53] | UK National Psychiatric Morbidity survey | M/F | The Revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R) | sd and dur | The Revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R) | 18 | 1 | Range 16–74; mean 44.75 | 2,406 | Age, sex, marital status, educational qualifications,occupational class, employment status, and other psychological symptoms |

| Gehrman et al. 2013 USA [51] | Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) | M/F | 2 items from PHQ and PCL-C, and questionnaires | sd and dur | PHQ-9 | 84 | 2 | Range NA; mean 33.1 | 8,902 | Sleep duration, birth year, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, and marital status |

| Suh et al. 2013 Korea [54] | Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) | M/F | Questionnaire | sd and dur | BDI | 72 | 3 | Range 43–73; mean 52.3 | 1,089 | Age, sex, education level, employment status, marital status, physical health, smoking status, heavy drinking, and time interactions with each covariate |

| Paudel et al. 2013 USA [52] | Prospective Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study | M | PSQI | sd, dur and day | Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | 40.8 | 1 | Range 67+; mean 75.9 | 2,352 | Age, clinic site, baseline GDS score, health status, education, use of benzodiazepines, alcohol consumption, cognitive function, walks for exercise, impairments in activities of daily living and certain medical conditions |

| Campbell et al. 2013 UK [50] | North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP) | M/F | Jenkins Sleep Questionnaire | sd and dur | HADS | 72 | 2 | Range 50+; mean ≥ 60 | 2,373 | Age, sex, marital status, employment status, alcohol intake, smoking status, and BMI |

| Jackson et al. 2014 Australia [55] | Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, (ALSWH) | F | Questionnaire | None (sleeping difficulties in the last 12 months) | Questionnaire | 108 | 3 | Range 22–27; mean < 60 | 5,702 | Education level, body weight dissatisfaction, history of abuse, and binge drinking in 2000 |

| Sivertsen et al. 2014 Norway [56] | Nord-Trøndelag health study HUNT Study (HUNT2 and HUNT3) | M/F | Questionnaire | sd, dur and day | HADS | 132 | 1 | Range 19–67; mean 45.3 (HUNT2) Range 20–89; mean 56.1 (HUNT3) | 44,270 | Age, sex, education, angina, arthrosis, asthma, ankylosing spondylitis, cancer, diabetes, fibromyalgia, headache, hypertension, myocardial infarction, obesity, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke and whiplash at baseline. |

| Dørheim et al. 2014 Norway [32] | Akershus Birth Cohort | F | BIS | sd, dur and day | EPDS | 3.5 | 2 | Range 17.4–47.5; mean 31.5 | 2,088 | No covariate adjustment |

Abbreviations: NA not available, F female, M male, NIHM National Institute of Mental Health, CES-D Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression, CBCL Child Behavior Checklist, EPDS Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, GMS Geriatric Mental State diagnostic schedule, TRF Teacher Report Form, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, DSM-12D 12-item scale for DSM depression, HAMD Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, SCID Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders, SPIKE Structured Psychopathological Interview and Rating of Social Consequences of Psychic Disturbances for Epidemiology, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, BDI Beck Depression Inventory, BIS The Bergen Insomnia Scale, PSG polysomnographic assessment, day daytime consequences criterion

§sd, sleep difficulties criterion

†dur, duration criterion

Table 2.

Quality assessment of studiesa

| Study source | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | Total score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non- exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur (> = 5 years) | Adequacy of follow up of cohorts (>80 %) | ||

| Ford and Kamerow [9] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Brabbins et al. [33] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Breslau et al. [34] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Chang et al. [18] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Weissman et al. [10] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Foley et al. [35] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Johnson et al. [36] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Mallon et al. [37] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Roberts et al. [17] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Roberts et al. [38] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Hein et al. [39] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Perlis et al. [40] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Morphy et al. [41] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Buysse et al. [20] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Cho et al. [19] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Jansson-Fröjmark and Lindblom [42] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Roane and Taylor [23] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Kim et al. [21] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Szklo-Coxe et al. [22] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Yokoyama et al. [43] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Jaussent et al. [45] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Almeida et al. [44] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Marques et al. [46] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Skapinakis et al. [53] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Salo et al. [49] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Suh et al. [54] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Paudel et al. [52] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Campbell et al. [50] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Jackson et al. [55] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Sivertsen et al. [56] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Okajima et al. [48] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Thomée et al. [47] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Gehrman et al. [51] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Dørheim et al. [32] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

aThe study quality was assessed according to the Newcastle Ottawa Quality assessment scale for cohort studies. This scale awards a maximum of 9 points to each study: 4 for selection, 2 for comparability, and 3 for assessment of outcomes (for cohort study). 1 = “Yes”, 0 = “No”, “Unable to determine” or “Not available”

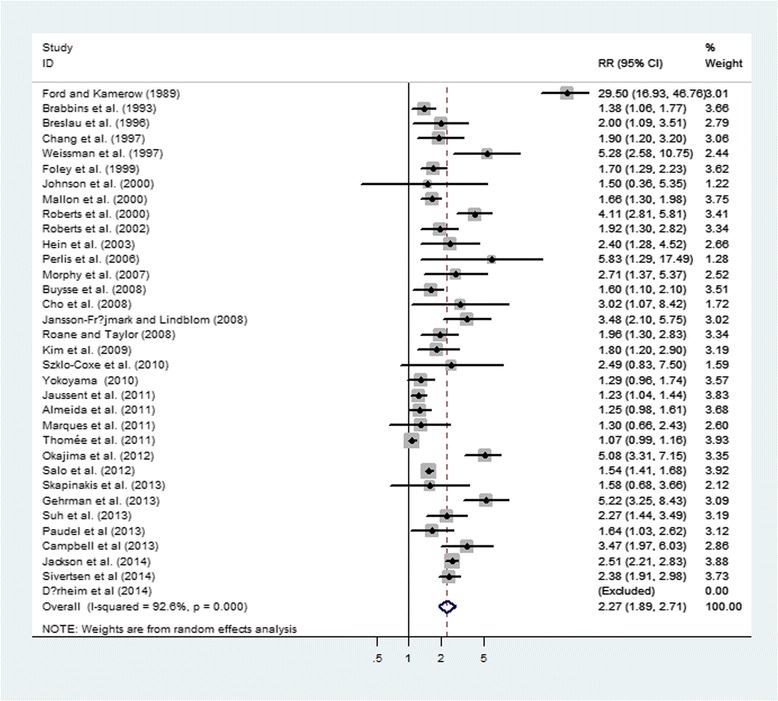

Quantitative synthesis

The results from the random-effects model combining the RRs for depression in relation to insomnia are shown in Fig. 2. Twenty-six studies suggested a significant positive relationship between insomnia and depression, while the other studies did not. The pooled RR of depression was 2.27 (95 % CI: 1.89–2.71) among populations with insomnia, and a high heterogeneity was observed among studies (I 2 = 92.6 %, P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the association between insomnia and risk of depression

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was conducted by mean age at baseline, sex, study location, insomnia definition, type of depression measurement, follow-up duration, sample size, study quality, publication year (before 2010 vs. after 2010), and whether age, socioeconomic status, smoking status, alcohol intake, body mass index (BMI) were controlled or not in models. Insomnia was significantly associated with an increased risk of depression in all subgroups, with the exception of populations from Australia (RR = 1.79, 95 % CI = 0.90–3.54, I 2 = 95.9 %, P < 0.001). However, moderate to high heterogeneities were observed. No interactions between insomnia and stratification variables in relation to depression risk were observed (all P values for interactions > 0.05; Table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of relative risks for the association between insomnia and depression

| No of studies | RR (95 % CI) | I 2 (%) | P value for heterogeneity | P value between groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at baseline, y | |||||

| <60 | 22 | 2.50 (1.96, 3.20) | 94.70 | <0.001 | 0.31 |

| ≥60 | 12 | 1.87 (1.47, 2.37) | 80.70 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 3 | 1.46 (1.13, 1.88) | 26.70 | 0.256 | 0.48 |

| Female | 3 | 1.96 (1.05, 3.66) | 73.50 | <0.001 | |

| Mixed | 28 | 2.41 (1.97, .95) | 92.80 | <0.001 | |

| Study location | |||||

| USA | 14 | 3.13 (2.03, 4.85) | 89.80 | <0.001 | 0.17 |

| Europe | 14 | 1.73 (1.43, 2.09) | 88.50 | <0.001 | |

| Asia | 4 | 2.27 (1.22, 4.21) | 90.40 | <0.001 | |

| Australia | 2 | 1.79 (0.90, 3.54) | 95.90 | <0.001 | |

| Source of participants* | |||||

| General population | 25 | 2.34 (1.85, 2.96) | 94.00 | <0.001 | 0.75 |

| Non-general population | 9 | 2.05 (1.53, 2.74) | 78.70 | <0.001 | |

| Insomnia definition | |||||

| Sd, dur and day | 11 | 2.90 (1.78, 4.74) | 92.70 | <0.001 | 0.37 |

| Sd and dur | 10 | 2.21 (1.50, 3.25) | 90.30 | <0.001 | |

| Sd | 13 | 1.87 (1.53, 2.29) | 87.70 | <0.001 | |

| Type of depression measure | |||||

| Self-reported scales | 17 | 2.20 (1.70, 2.86) | 94.10 | <0.001 | 0.63 |

| Physician diagnosis | 15 | 2.27 (1.67, 3.09) | 91.80 | <0.001 | |

| Combined | 2 | 3.89 (1.73, 8.74) | 0.00 | 0.438 | |

| Follow-up duration, y | |||||

| <5 | 22 | 2.34 (1.84, 2.97) | 93.60 | <0.001 | 0.77 |

| 5–10 | 8 | 2.37 (1.73, 3.25) | 82.30 | <0.001 | |

| >10 | 4 | 1.88 (1.52, 2.32) | 54.60 | 0.086 | |

| Sample size | |||||

| <5000 | 26 | 2.01 (1.66, 2.44) | 86.50 | <0.001 | 0.10 |

| ≥5000 | 8 | 3.12 (2.11, 4.62) | 96.40 | <0.001 | |

| Study quality | |||||

| Score >7 | 8 | 2.06 (1.60, 2.63) | 88.60 | <0.001 | 0.70 |

| Score ≤ 7 | 26 | 2.36 (1.83, 3.03) | 93.00 | <0.001 | |

| Publication year | |||||

| Before 2010 | 19 | 2.63 (1.95, 3.55) | 88.20 | <0.001 | 0.21 |

| 2010–2014 | 15 | 1.94 (1.53, 2.45) | 94.62 | <0.001 | |

| Statistical model | |||||

| Unadjusted | 5 | 1.78 (1.29, 2.47) | 56.00 | 0.078 | 0.75 |

| Adjusted | 29 | 2.31 (1.90, 2.81) | 93.40 | <0.001 | |

| Controlling age in models | |||||

| Yes | 21 | 2.64 (2.04, 3.42) | 92.30 | <0.001 | 0.09 |

| No | 13 | 1.75 (1.33, 2.31) | 92.50 | <0.001 | |

| Controlling SES in models | |||||

| Yes | 17 | 2.34 (1.81, 3.03) | 95.60 | <0.001 | 0.78 |

| No | 17 | 2.15 (1.74, 2.65) | 71.60 | <0.001 | |

| Controlling smoking status in models | |||||

| Yes | 7 | 2.10 (1.45, 3.06) | 89.80 | <0.001 | 0.75 |

| No | 27 | 2.32 (1.88, 2.87) | 93.30 | <0.001 | |

| Controlling alcohol intake in models | |||||

| Yes | 9 | 2.47 (1.75, 3.48) | 90.90 | <0.001 | 0.69 |

| No | 25 | 2.19 (1.78, 2.69) | 92.00 | <0.001 | |

| Controlling BMI in models | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 2.19 (1.57, 3.06) | 85.30 | <0.001 | 0.94 |

| No | 29 | 2.28 (1.87, 2.78) | 92.30 | <0.001 | |

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index, dur duration criterion, day daytime consequences criterion, F female, M male, NA not available, SES socioeconomic status, Sd sleep difficulties criterion

*Study population truly or somewhat representative of a community or population-based study defined as general population, and study population was sampled from a special population (such as population from a company, register patients, data from the health insurance company or health examination organization or pregnant), which defined as non-general populations

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were used to identify the potential sources of heterogeneity in association between insomnia and the risk of depression. This helped to examine the influence of various exclusions on the combined RR and test the stability of the quantitative synthesis results. In the leave-one-out analysis by omitting one study in turn, the overall combined RR did not change substantially, with a range from 2.07 (95 % CI: 1.77–2.42) to 2.33 (95 % CI: 1.95–2.78), and I 2 varied from 89.6 to 89.9 %. This indicated that none of the individual studies significantly influenced the overall result. It was worth noting that, six studies [32, 38, 41, 49, 50, 54] defined insomnia as DIS and/or DMS or NRS, and the rest of studies defined insomnia as DIS and/or DMS. There is controversy as to whether individuals with NRS complaint share similar pathophysiologic mechanisms with the other nocturnal symptoms, such as DIS and DMS. Restricting the analysis to the 28 studies defined insomnia as DIS and/or DMS yielded a pooled RR of 2.30 (95 % CI, 1.84 to 2.87) after exclusion of 6 studies. Thus, our main results would not change even if these six studies were excluded.

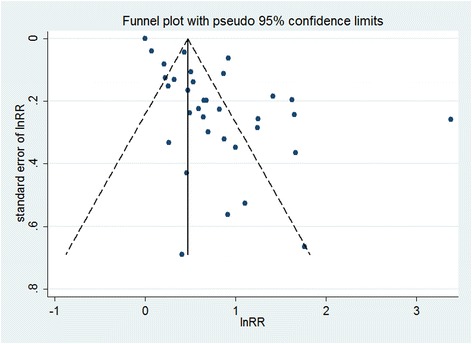

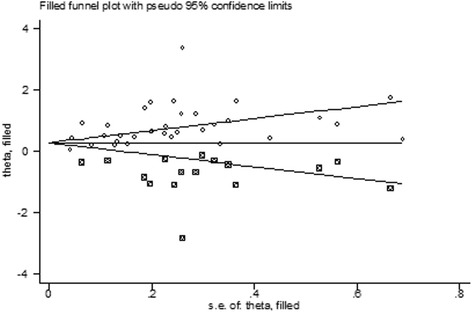

Publication bias

The visual inspection of the funnel plot identified substantial asymmetry (Fig. 3). The Egger’s test identified evidence of substantial publication bias (P < 0.05). A sensitivity analysis using the trim-and-fill method was performed with 16 imputed studies, which produced a symmetrical funnel plot (Fig. 4). Using the trim-and-fill method, the RR was 1.40 (95 % CI, 1.16–1.69; P < 0.001). Correction for potential publication bias thus did not alter the significant association.

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot with pseudo 95 % confidence limits of insomnia and depression. The horizontal line represents the summary effect estimates, and the dotted lines are pseudo 95 % CIs

Fig. 4.

Filled funnel plot of RR from studies that investigated the association between insomnia and the risk of depression. The circles alone are real studies and the circles enclosed in boxes are ‘filled’ studies. The horizontal line represents the summary effect estimates, and the diagonal lines represent pseudo-95 % CI limits

Discussion

The results of this meta-analysis of 34 prospective cohort studies showed that insomnia was significantly associated with an increased risk of depression. The pooled estimates (RR = 2.27; 95 % CI: 1.89–2.71) indicated that participants with insomnia, compared to those free of it, experienced more than two-fold risk to develop depression. Furthermore, the association remained significant in most subgroup analyses.

Comparison with previous study

Our findings were approximately consistent with those from the meta-analysis by Baglioni et al. in 2011 [24], which also showed that sleep difficulty was significantly associated with depression. The results of this current meta-analysis generally concur and further complement the findings of previous review in several important aspects. The present meta-analysis included 15 new prospective cohort studies with larger sample sizes and many more cases, which significantly enhanced the statistical power to detect potential association between insomnia and depression risk. Additionally, the previous review did not investigate any subgroups other than age. More importantly, compared with the previous review, the OR was corrected to more approximately the true RR in the present study, therefore our risk estimate is more accurate and a reliable. Of note, the associations differed among populations of different ethnic backgrounds were investigated in the present study. The current meta-analysis showed that the increased risk was more pronounced for participants from the United States than for European participants. However, no statistically significant association was observed in Australian populations, which might result from the limited number of included studies (two studies comprising 13,323 participants). In order to make the finding generalize to other populations, more studies are warranted to be conducted in other populations from Asia, Africa and South America.

There were several possible biological mechanisms through which insomnia in general may increase the risk of depression. Sleep disturbance may play a key role in the development of depression. Experimental studies showed that sleep loss may result in cognitive and affective alterations that lead to depression risk [55]. Alternatively, sleep disturbance impaired emotional regulation and stability [59] and may alter neural processes that may result in the symptomatology of depression [60]. Secondly, sustained arousal and chronic activation of hyperactivity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, the major neuroendocrine mediator of stress response, have been suggested as playing a vital role in the development of depression in insomniacs with objective short sleep duration [14, 61]. Finally, other proposed mechanisms by which insomnia might increase the risk of depression included increasing levels of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [62–64], which indicated low-level systemic inflammation was a predictor of depression development [65].

Long-term, double-blind, randomized controlled trials provided the best evidence on the effect between insomnia and depression. Recently, the study by Gosling et al. [66] showed that an internet-based insomnia intervention would indeed reduce the risk of depression. The role of insomnia treatment in modulating subsequent risk of depression needs to be studied further.

Strengths and limitations

Our review is very valuable and crucial though it is an updated meta-analysis. First, our review added more than 3 times as many participants as the previous review, which provided stronger and more sufficient evidence. Second, the prospective nature of the included studies avoided the influence of recall and selection bias. Third, more studies from additional areas other than the North America and Europe were included, which increased the generalizability. Fourth, we did stratified analyses to explore whether the results were influenced by some confounding factors, and the consistent results from the sensitivity and subgroup analyses indicated that our findings were reliable and robust.

There are also some limitations in this meta-analysis. Firstly, the accuracy of our results might be influenced by the differences of the measurement criteria of insomnia and depression. However, no significant differences among groups were observed for the type of insomnia and depression measurement in this study. Secondly, we were unable to independently summarize the evidence of individual types of insomnia symptoms on depression risk due to no sufficient information in the original studies. Thirdly, although we extracted the most fully adjusted risk estimates, the adjusted confounders varied among the included studies. Some important confounding factors that might influence the relationship between insomnia and depression risk were gender, age, smoking, education, alcohol or drug abuse, other somatic or psychiatric disease, medication status, and social status. These important confounders were not fully adjusted in some of the included studies, which might influence the accuracy of the results. Finally, publication bias were detected, however, we used trim-and-fill method to correct the bias, which did not alter the significant positive association between insomnia and depression risk.

Based on our findings, we suggest that future research in this field is warranted, especially the long-term prospective cohort studies about the association between individual insomnia symptoms and depression. In addition, more interventional studies are necessary to explore the underlying mechanisms that link insomnia and depression.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this meta-analysis supports the hypothesis that insomnia is associated with an increased risk of depression. Considering the increasing prevalence of insomnia worldwide and the heavy burdens of depression, the results of our study provide practical and valuable clues for the prevention of depression and the study of its etiology.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the authors of the studies included in our meta-analysis.

Funding

No funding was received for this systematic review.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

LQL and ZXL conceived the study. CMW and YG searched and checked the databases according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. LQL and ZXL helped to develop search strategies. CMW and YG extracted the data and assessed their quality. CMW, YG and XGQ analyzed the data. CMW gave advice on meta-analysis methodology. LQL wrote the draft of the paper. All authors contributed to reviewing or revising the paper and read and approved the final manuscript. ZXL is the guarantor of this work and had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for its integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval is not required for this review.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidential interval

- CNKI

China national knowledge infrastructure

- DIS

Difficulties in initiating sleep

- DMS

Difficulties in maintaining sleep

- DSM-IV-TR

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- GBD

Global burdens of disease

- HPA

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- MOOSE

Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology

- NRS

Non-restorative sleep

- OR

Odds ratio

- RR

Relative risk.

Contributor Information

Liqing Li, Email: liliqing_lily@163.com.

Chunmei Wu, Email: wuchunmei08@gmail.com.

Yong Gan, Email: scswj2008@163.com.

Xianguo Qu, Email: quxianguo@163.com.

Zuxun Lu, Phone: +86-27-83693756, Email: zuxunlu@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Solomon A, Haaga DA, Arnow BA. Is clinical depression distinct from subthreshold depressive symptoms? A review of the continuity issue in depression research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(8):498–506. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200108000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349(9064):1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global Burden of Disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020 summary. 1st edition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996.

- 4.Organization WH. The World health report: 2001: Mental health : new understanding, new hope. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Services USDoHaH . Mental health: a report of the surgeon general. Rockville: Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Services USDoHaH. Report of the 2005 White House Conference on aging. The booming dynamics of aging: from awareness to action. Washington, DC; 2006. http://nicoa.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/05/2005-WHCOA-Final-Report.pdf.

- 7.Neckelmann D, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Chronic insomnia as a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression. Sleep. 2007;30(7):873–880. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), 4th Edition, Text Revision. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262(11):1479–1484. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03430110069030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissman MM, Greenwald S, Nino-Murcia G, Dement WC. The morbidity of insomnia uncomplicated by psychiatric disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19(4):245–250. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(97)00056-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohayon MM. Prevalence of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of insomnia: distinguishing insomnia related to mental disorders from sleep disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31(3):333–346. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3956(97)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leger D, Guilleminault C, Dreyfus JP, Delahaye C, Paillard M. Prevalence of insomnia in a survey of 12,778 adults in France. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(1):35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(2):97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN. Insomnia and its impact on physical and mental health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(12):418. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0418-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillin JC. Are sleep disturbances risk factors for anxiety, depressive and addictive disorders? Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1998;393:39–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb05965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vollrath M, Wicki W, Angst J. The Zurich study. VIII. Insomnia: association with depression, anxiety, somatic syndromes, and course of insomnia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1989;239(2):113–124. doi: 10.1007/BF01759584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts RE, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA, Strawbridge WJ. Sleep complaints and depression in an aging cohort: A prospective perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(1):81–88. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang PP, Ford DE, Mead LA, Cooper-Patrick L, Klag MJ. Insomnia in young men and subsequent depression. The Johns Hopkins precursors study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(2):105–114. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Irwin MR. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543–1550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep. 2008;31(4):473–480. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Insomnia, depression, and physical disorders in late life: a 2-year longitudinal community study in Koreans. Sleep. 2009;32(9):1221–1228. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.9.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szklo-Coxe M, Young T, Peppard PE, Finn LA, Benca RM. Prospective associations of insomnia markers and symptoms with depression. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(6):709–720. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roane BM, Taylor DJ. Adolescent insomnia as a risk factor for early adult depression and substance abuse. Sleep. 2008;31(10):1351–1356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, Lombardo C, Riemann D. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M. The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available at http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 27.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace BC, Schmid CH, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Meta-Analyst: software for meta-analysis of binary, continuous and diagnostic data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorheim SK, Bjorvatn B, Eberhard-Gran M. Can insomnia in pregnancy predict postpartum depression? A longitudinal, population-based study. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brabbins CJ, Dewey ME, Copeland JRM, Davidson IA, McWilliam C, Saunders P, Sharma VK, Sullivan C. Insomnia in the elderly : Prevalence, gender differences and relationships with morbidity and mortality. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8(6):473–480. doi: 10.1002/gps.930080604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39(6):411–418. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Izmirlian G, Hays JC, Blazer DG. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults in a biracial cohort. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson EO, Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Trouble sleeping and anxiety/depression in childhood. Psychiatry Res. 2000;94(2):93–102. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mallon L, Broman JE, Hetta J. Relationship between insomnia, depression, and mortality: a 12-year follow-up of older adults in the community. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12(3):295–306. doi: 10.1017/S1041610200006414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen IG. Impact of insomnia on future functioning of adolescents. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(1):561–569. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hein S, Bonsignore M, Barkow K, Jessen F, Ptok U, Heun R. Lifetime depressive and somatic symptoms as preclinical markers of late-onset depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253(1):16–21. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perlis ML, Smith LJ, Lyness JM, Matteson SR, Pigeon WR, Jungquist CR, Tu X. Insomnia as a risk factor for onset of depression in the elderly. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4(2):104–113. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0402_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morphy H, Dunn KM, Lewis M, Boardman HF, Croft PR. Epidemiology of insomnia: a longitudinal study in a UK population. Sleep. 2007;30(3):274–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jansson-Frojmark M, Lindblom K. A bidirectional relationship between anxiety and depression, and insomnia? A prospective study in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(4):443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yokoyama E, Kaneita Y, Saito Y, Uchiyama M, Matsuzaki Y, Tamaki T, Munezawa T, Ohida T. Association between depression and insomnia subtypes: a longitudinal study on the elderly in Japan. Sleep. 2010;33(12):1693–1702. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.12.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almeida OP, Alfonso H, Yeap BB, Hankey G, Flicker L. Complaints of difficulty to fall asleep increase the risk of depression in later life: the health in men study. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1-3):208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaussent I, Bouyer J, Ancelin ML, Akbaraly T, Peres K, Ritchie K, Besset A, Dauvilliers Y. Insomnia and daytime sleepiness are risk factors for depressive symptoms in the elderly. Sleep. 2011;34(8):1103–1110. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marques M, Bos S, Soares MJ, Maia B, Pereira AT, Valente J, Gomes AA, Macedo A, Azevedo MH. Is insomnia in late pregnancy a risk factor for postpartum depression/depressive symptomatology? Psychiatry Res. 2011;186(2-3):272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomee S, Harenstam A, Hagberg M. Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults--a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okajima I, Komada Y, Nomura T, Nakashima K, Inoue Y. Insomnia as a risk for depression: a longitudinal epidemiologic study on a Japanese rural cohort. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(3):377–383. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salo P, Sivertsen B, Oksanen T, Sjosten N, Pentti J, Virtanen M, Kivimaki M, Vahtera J. Insomnia symptoms as a predictor of incident treatment for depression: prospective cohort study of 40,791 men and women. Sleep Med. 2012;13(3):278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell P, Tang N, McBeth J, Lewis M, Main CJ, Croft PR, Morphy H, Dunn KM. The role of sleep problems in the development of depression in those with persistent pain: a prospective cohort study. Sleep. 2013;36(11):1693–1698. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gehrman P, Seelig AD, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ, Hooper TI, Gackstetter GD, Ulmer CS, Smith TC. Predeployment sleep duration and insomnia symptoms as risk factors for new-onset mental health disorders following military deployment. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1009–1018. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paudel M, Taylor BC, Ancoli-Israel S, Blackwell T, Maglione JE, Stone K, Redline S, Ensrud KE. Sleep disturbances and risk of depression in older men. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1033–1040. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skapinakis P, Rai D, Anagnostopoulos F, Harrison S, Araya R, Lewis G. Sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms: an investigation of their longitudinal association in a representative sample of the UK general population. Psychol Med. 2013;43(2):329–339. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suh S, Kim H, Yang HC, Cho ER, Lee SK, Shin C. Longitudinal course of depression scores with and without insomnia in non-depressed individuals: a 6-year follow-up longitudinal study in a Korean cohort. Sleep. 2013;36(3):369–376. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jackson ML, Sztendur EM, Diamond NT, Byles JE, Bruck D. Sleep difficulties and the development of depression and anxiety: a longitudinal study of young Australian women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(3):189–198. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sivertsen B, Lallukka T, Salo P, Pallesen S, Hysing M, Krokstad S, Simon O. Insomnia as a risk factor for ill health: results from the large population-based prospective HUNT Study in Norway. J Sleep Res. 2014;23(2):124–132. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). American Psychiatric; 2000.

- 58.Foley DJ, Monjan A, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults: an epidemiologic study of 6,800 persons over three years. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S366–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoo SS, Gujar N, Hu P, Jolesz FA, Walker MP. The human emotional brain without sleep--a prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Curr Biol. 2007;17(20):R877–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Novati A, Roman V, Cetin T, Hagewoud R, den Boer JA, Luiten PG, Meerlo P. Chronically restricted sleep leads to depression-like changes in neurotransmitter receptor sensitivity and neuroendocrine stress reactivity in rats. Sleep. 2008;31(11):1579–1585. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.11.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Balbo M, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep and its disturbances on hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Int J Endocrinol. 2010;2010:759234. doi: 10.1155/2010/759234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Okun ML, Luther JF, Wisniewski SR, Wisner KL. Disturbed sleep and inflammatory cytokines in depressed and nondepressed pregnant women: an exploratory analysis of pregnancy outcomes. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(7):670–681. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31829cc3e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Faraut B, Boudjeltia KZ, Vanhamme L, Kerkhofs M. Immune, inflammatory and cardiovascular consequences of sleep restriction and recovery. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(2):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gimeno D, Kivimaki M, Brunner EJ, Elovainio M, De Vogli R, Steptoe A, Kumari M, Lowe GD, Rumley A, Marmot MG, et al. Associations of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 with cognitive symptoms of depression: 12-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychol Med. 2009;39(3):413–423. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Valkanova V, Ebmeier KP, Allan CL. CRP, IL-6 and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):736–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gosling JA, Glozier N, Griffiths K, Ritterband L, Thorndike F, Mackinnon A, Hehir KK, Bennett A, Bennett K, Christensen H. The GoodNight study--online CBT for insomnia for the indicated prevention of depression: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:56. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article.