Abstract

Externalizing symptoms, such as aggression, impulsivity, and inattention, represent the most common forms of childhood maladjustment (Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000). Several dimensions of parenting behavior, including overreactive and warm parenting, have been linked to children’s conduct problems. However, the majority of these studies involve biologically-related family members, thereby limiting understanding of the role of genetic and/or environmental underpinnings of parenting on child psychopathology. This study extends previous research by exploring associations between overreactive and warm parenting during toddlerhood and school-age externalizing problems, as well as the potential moderating effects of child effortful control (EC) on such associations using a longitudinal adoption design. The sample consisted of 225 adoption-linked families (adoptive parents, adopted child [124 male and 101 female] and birth parent[s]), thereby allowing for a more precise estimate of environmental influences on the association between parenting and child externalizing problems. Adoptive mothers’ warm parenting at 27 months predicted lower levels of child externalizing problems at ages 6 and 7. Child EC moderated this association in relation to teacher reports of school-age externalizing problems. Findings corroborate prior research with biological families that was not designed to unpack genetic and environmental influences on associations between parenting and child externalizing problems during childhood, highlighting the important role of parental warmth as an environmental influence.

Keywords: Externalizing problems, warm parenting, effortful control, adoption

Externalizing symptoms, such as aggression, impulsivity, and inattention, represent the most common forms of childhood maladjustment (Campbell et al., 2000). Empirical interest in early childhood behavior problems has been fueled by evidence of a link between early onset of externalizing problems and antisocial behavior disorders in later childhood and adolescence (Aguilar, Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 2000; Odgers et al., 2008). Specifically, epidemiological and developmental studies, some starting as early as age 2, have found aggressive behavior to be highly stable, particularly among males (Hofstra, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2002). For these reasons, research is needed to illuminate early risk factors for externalizing problems in the interest of informing effective prevention and intervention efforts.

Direct Effects of Early Childhood Parenting on Later Externalizing Problems

Several dimensions of parenting during early childhood have been linked to children’s later externalizing problems. In particular, overreactive (harsh, irritable, or angry) parenting has been consistently associated with externalizing problems during early childhood and the early school-age years (Campbell et al., 2000; Maccoby, 2000; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994; Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003). The specific behaviors comprising overreactive parenting include yelling, threatening, using physical aggression, frequent negative commands, name-calling, criticism, and unreasonable expectations. The current study builds on the existing literature suggesting that when parents fail to control their own emotions during interactions and rely on overreactive parenting, it reinforces angry emotions in children (Dix, 1991; Scaramella & Leve, 2004), distresses children (Morris et al., 2002; O’Leary, Slep, & Reid, 1999), and affects the ability of children to regulate their emotions (Chang, Olson, Sameroff, & Sexton, 2011; Eisenberg et al., 1999). Negative dimensions of parenting, such as overreactive parenting, have received the majority of attention in the literature on predictors of child externalizing problem behavior, with fewer studies exploring whether dimensions of positive parenting can protect children from developing externalizing problems (Boeldt et al., 2012; Gardner, 1994). Some investigators have suggested that positive parenting might predict children’s externalizing problem behavior through its effects on the development of children’s emotion-related regulation, which includes the modulation of emotion-related physiological responses, motivational states, felt experience, and associated behaviors (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998). In addition, high levels of positive parenting foster the development of child negotiation and conflict-resolution skills, affording children skills to manage interpersonal relations and reducing their reliance on noncompliant or oppositional tactics (Kochanska, 1993; Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon, Lengua, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research, 2000). There have been relatively few studies that have examined the relation between positive or negative parenting behaviors and children’s behavior problems while accounting statistically for the other (e.g., Denham et al., 2000; Gardner, Shaw, Dishion, Burton, & Supplee, 2007; McKee, Colletti, Rakow, Jones, & Forehand, 2008). The design of the current study afforded an opportunity to examine the extent to which warm parenting and overreactive parenting during toddlerhood each independently predict later child behavior in the school age period using teacher reports of externalizing problems.

Another shortcoming of the research on the effect of parenting on later child externalizing problems is the lack of information on the role of fathers. Generally, fathers’ influences on child outcomes have been ignored in the literature (Lamb, 2004; Phares & Compas, 1992). Although associations between parental behaviors and child externalizing symptoms generally are stronger for mothers than for fathers (Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994), several studies have documented the importance of paternal influences on child behavior problems (e.g., DeKlyen, Speltz, & Greenberg, 1998; Denham et al., 2000). Recently, fathers have a greater role in the rearing of children, especially in dual-earner families (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004; Wall & Arnold, 2007). For these reasons, associations with both maternal and paternal parenting on child externalizing problems will be examined.

The Confound of Passive Genotype-Environment Correlation in Prior Family Research

Past research examining associations between overreactive and warm parenting and externalizing problems has typically been conducted with biologically-related parents and children (Boeldt et al., 2012; Campbell et al., 2000; Shaw et al., 2003). In typical studies of biologically-related family members, it is impossible to ascertain whether associations between family-level variables and child outcomes represent environmental effects or shared genetic influences (Plomin, DeFries, Knopik, & Neiderheiser, 2013; Plomin, DeFries, & Loehlin, 1977; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). That is, genes may not only affect the specific index of behavior considered (e.g., externalizing problems), but may also affect the rearing environment that children experience (e.g., marital conflict, overreactive parenting practices). Thus, the effects of parenting on children’s externalizing problems may be due to shared genes through passive genotype-environment correlation (rGE) as well as to direct effects of parenting behaviors (Plomin et al., 1977; Price & Jaffee, 2008; Scarr & McCartney, 1983).

The adoption design of the current investigation offers a rare opportunity to examine the association of parenting and child outcomes where the potential confounding influence of passive rGE is removed. In the present study, the influence of shared genes on parenting behavior and child characteristics is eliminated by studying children adopted at birth by non-relatives. The study therefore advances a core objective outlined by Rutter, Pickles, Murray, and Eaves (2001) in testing causal hypotheses relating to environmental influences on children’s psychological outcomes: to identify environmental factors where confounding genetic factors have been accounted for.

Moderating Effect of Temperament on the Association between Parenting and Externalizing Problems

In addition to parenting, several dimensions of temperament during early childhood have been linked to children’s externalizing problems, both independently and jointly with parenting (Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011). Temperament has been defined as individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart & Bates, 1998). During early childhood, dimensions of temperament such as negative emotionality (Lipscomb et al., 2012), novelty seeking (Tremblay, Pihl, Vitaro, & Dobkin, 1994), and resistance to control (Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1998) have been positively associated with externalizing problems. Although several dimensions of temperament have been implicated in the development of externalizing problems, effortful control (EC; Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, & Wellman, 2005), plays a particularly important role. EC is linked to processing relevant information, modulating affective arousal, integrating information, and inhibiting inappropriate behavior (Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Reiser, 2000). Poor EC has been implicated in the development of children’s externalizing problems (Olson et al., 2005), including studies of toddlers and preschoolers (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Olson et al., 2005), and school-age children, and adolescents (Eisenberg et al., 2005; Eisenberg et al., 2004). In sum, research has established longitudinal associations between low EC and later externalizing problems, yet EC has typically been investigated without accounting for the contribution of other contextual factors.

Although most studies document coherence among different components of EC, EC comprises potentially dissociable domains of attentional control, activational control, and inhibitory control, all of which may have unique implications for adjustment (Kindlon et al., 1995; Nigg, Goldsmith, & Sachek, 2004; Rothbart & Rueda, 2005). As a complex trait, EC cannot be reliably measured by assessing a singular facet or dimension (Murray & Kochanska, 2002). Distinct tasks are often used to examine each aspect of EC, such as delay of gratification tasks typically measuring inhibitory control and Stroop tasks measuring attentional control. Importantly, few studies have examined whether these dimensions of EC uniquely relate to measures of child adjustment, in particular externalizing problems.

While several studies have established direct effects between multiple dimensions of caregiving and later externalizing problems in isolation from other child factors, Bates and Pettit (2007) have argued that temperament and parenting should be examined within the context of their interaction, as the effects of parenting might depend on children’s temperament, and interactions between parenting and child temperament might account for complexity in developmental processes. There is an increasingly rich literature on how dimensions of temperament, such as frustration, impulsivity, negative emotionality, and effortful control, interact with positive and negative dimensions of parenting. Although a detailed review of this literature is beyond the scope of this article, overall, children’s frustration, low effortful control or self-regulation, and high impulsivity increase children’s risk for externalizing behavior problems, particularly in the face of negative parenting or inappropriate control (Bates, Schermerhorn, & Petersen, 2014; Kiff et al., 2011). Several models have been posited to describe how children’s temperamental characteristics lead to variation in sensitivity to rearing behaviors (i.e., vulnerability model, biological sensitvity to context, differential susceptibility; Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Boyce & Ellis, 2005). Rather than adopting a particular model for examining the associations between parenting, temperament, and child adjustment, we chose to examine more generally how individual differences in children’s effortful control might moderate the effects of warm parenting on child externalizing problems. For example, it may be that children with low levels of EC may benefit more from concurrent levels of parental warmth than children who are able to regulate on their own because higher levels of parental warmth might reinforce and promote on-task, less impulsive, and more planful behavior.

Genetic Contributions to Externalizing Problems

Twin and adoption studies provide evidence that externalizing problems are influenced by both heritable and environmental factors (Rhee & Waldman, 2002). In a meta-analysis of 103 twin and adoption studies on antisocial behavior, Burt (2009) found that genetic factors account for over half of the total variance in aggressive behavior. The results of these studies underscore the importance of accounting for inherited influences on externalizing problems, and as an advantage of the current study’s adoption design, inherited influences can be ascertained independently of environmental influences on children’s externalizing problem behavior by measuring birth parent externalizing behavior.

Current Study

There have been relatively few attempts to examine the extent to which warm and overreactive parenting independently predict patterns of adjustment in school-age children. The adoption design allows for a more precise estimate of environmental effects on the association between parenting behavior and children’s externalizing problems. There is also a dearth of literature examining the potential moderating role of child EC on the magnitude of association between parenting and later externalizing problems. Finally, few genetic studies of aggressive and delinquent behaviors in childhood and adolescence have relied on teachers’ reports, with the majority of studies using parents’ reports or adolescents’ self-reports (Rhee & Waldman, 2002). The current study relied on teacher reports for several reasons. First, teacher reports of children’s externalizing problems are particularly good predictors of concurrent and subsequent adjustment (Arseneault et al., 2003; Deater-Deckard & Plomin, 1999; Verhulst, Koot, & Van der Ende, 1994). Second, teachers are able to compare each child to a broader reference group of children. Teachers also observe children’s behavior in a classroom environment that provides opportunities for peer interactions that include aggressive and delinquent behavior. In contrast, parents typically observe children’s behavior at home and with other family members. Finally, because we relied on parent reports to index warm and overreactive parenting, using teacher reports of externalizing problem behavior reduced the likelihood of informant bias in inflating associations between parenting and child externalizing problems.

The study had two primary aims. First, we sought to examine the main effect of adoptive parent warm and overreactive parenting, measured in the toddler period, on children’s externalizing problems, assessed by teachers at ages 6 and 7. Based on evidence suggesting a negative association between warm parenting and later child externalizing problems, it was hypothesized that higher levels of adoptive mother and father warm parenting at 27 months would be associated with lower levels of school age externalizing problems after accounting for externalizing problem behavior in biological parents (Boeldt et al., 2012), and eliminating the effects of passive gene-environment correlation on adoptive parent-child correlations by incorporating an adoption study design. Based on previous research suggesting a positive association between overreactive parenting and externalizing problem behavior, we hypothesized that higher levels of adoptive mother overreactive parenting at 27 months would be associated with higher levels of school-age externalizing problems. Second, we sought to examine the moderating role of child EC on associations between adoptive parent warm and overreactive parenting and school-age externalizing problems. Based on previous research showing that children vary in their sensitivity to supportive parenting based on levels of EC, it was hypothesized that low levels of child EC at 27 months would attenuate the negative association between adoptive mother and father warm parenting and school-age externalizing problems. Additionally, it was hypothesized that low levels of child EC at 27 months would amplify the positive association between adoptive mother and father overreactive parenting and child externalizing problems. The design of this study has several methodological strengths, including the use of a prospective adoption design with assessments of birth mothers’ externalizing problem behavior and adoptive parents’ warm and overreactive parenting, a longitudinal design that followed children’s development from toddlerhood to the school-age period, and the use of multiple informants and methods, including observations and standardized questionnaires.

Method

Sample

The sample includes 361 adoptive families participating in Cohort I of the Early Growth and Development Study, an ongoing, multisite, longitudinal study of adopted children, adoptive parents, and birth parents (Leve et al., 2013). Cohort I participants were enrolled between 2003 and 2006 using a rolling recruitment procedure in three regions of the United States: Mid-Atlantic, West/Southwest, and Pacific Northwest (N = 33 agencies in 10 states). Adoption agencies reflected a range of adoption agencies in the United States: public, private, religious, and secular, with both open and closed adoption philosophies. Study participants met the following eligibility criteria: (a) the adoption placement was domestic, (b) the infant was placed within 3 months postpartum, (c) the infant was placed with a nonrelative adoptive family, (d) the infant had no known major medical conditions such as extreme prematurity or extensive medical surgeries, and (e) the birth and adoptive parents were able to read or understand English at the eighth-grade level.

A subsample of 225 of the original 361 adoptive families was examined in this study. The subsample was selected based on having available teacher’s report of child externalizing problems at ages 6 and/or 7 (more details below about sample selection). The subsample included male (55%) and female (45%) children with a range of racial backgrounds (59.1% White, 11.6% Black/ African American, 8.4% Latino, 20.0% multiracial, 0.3% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 0.4% unknown or not reported). Adoptive parents were predominantly White (over 90% of adoptive mothers/fathers) and involved in a stable marital or marriage-like relationship (M = 18.5 years, SD = 5.2 at first assessment). The median household income for adoptive families was $70,000-$100,000, which is higher than the average US household income of $54,489 (DeNavas-Walt, 2010). Same sex couples were excluded from the present study because of our focus on mother- and father-specific influences. Birth mothers tended to be younger (M age = 24.1, SD = 5.9) than adoptive mothers (M age = 37.8, SD = 5.5) and fathers (M age = 38.4, SD = 5.8) at the time of the child’s birth and of a lower socioeconomic status (typically high school or trade). The median household income for birth families was <$15,000. For demographic information on the full sample, please see Leve et al. (2013).

Children’s teachers were invited to report on children’s behavior in the school setting. We combined data from the two assessments (age 6 and 7) in order to maximize the sample size. Composition was supported on empirical grounds by a moderate correlation between externalizing scores across ages 6 and 7 (r(92) = .49). Teacher data were available for 225 participants, primarily due to teacher nonresponsiveness. When those participants with and without teacher ratings were compared, those with missing data had birth mothers with higher externalizing scores compared to those children with teacher ratings t(183) = 3.53, p < .001, and had adoptive mothers with higher levels of warm parenting than those retained in further analyses t(294) = 2.22, p < .05.

For purposes of the current study, data from the child age 3-6 month assessment were used to obtain information from birth parents about their externalizing problems. Observations of child EC and adoptive parents’ reports about parenting were obtained from an in-home assessment when children were 27 months old. Teachers’ reports of school-age externalizing problems were collected at ages 6 and 7. Home assessments for adoptive families ranged in length from 2.5 to 4 hours. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the participating institutions and informed consent was obtained from all participants (adoptive parents, children, biological parents, and teachers).

Measures

Adoptive parent warm parenting

Adoptive mother and father warm parenting was assessed using the 6-item Warmth subscale from the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby & Conger, 2001) at 27 months (adoptive mother α = .81; adoptive father α = .84). Adoptive parents reported on their own warmth toward their child on a 7-point scale ranging from never to always with high scores indicating greater warmth (e.g. “Let him/her know you really care about him/her,” “Act loving and affectionate towards him/her,” and “Tell him/her you love him/her.”)

Adoptive parent overreactive parenting

Adoptive parent self-reported overreactivity was measured by the 10-item overreactivity subscale of the Parenting Scale (Arnold, O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker, 1993) at 27 months (adoptive mother α = .68, adoptive father α = .65). The scale was designed to identify parental discipline mistakes that relate theoretically to externalizing problems such as harsh, irritable, and angry parenting behaviors, with higher scores indicating more parental overreactivity. Each identified mistake was paired with its more effective counterpart to form the anchors for a 7-point scale (e.g., when I’m upset or under stress…1= I am no more picky than usual; 7 = I am picky and on my child’s back. When my child misbehaves…1= I speak to my child calmly; 7 = I raise my voice or yell).

Child EC

Two validated EC tasks for young children, administered at the 27-month assessment, were used: a shape stroop task and a gift delay task (Leve et al., 2013). Both tasks were videotaped and coded by trained interview staff who were required to have a bachelor’s degree and a year of research experience or an equivalent combination of training and experience. First, the shape stroop task was administered (Carlson, Mandell, & Williams, 2004; Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000) as a measure of attentional control. In this task, an interviewer showed the child three large and three small pictures of the same fruits (apple, banana, orange). After reviewing the names and the meaning of each big–little dimension, the interviewer showed the child three pictures, each containing a small fruit embedded within a different large fruit (e.g., a small orange inside of a large apple). The interviewer then asked the child to point to each of the little fruits. The prepotent response for young children is to point to the large fruit. After the fruit trials, the interviewer repeated the activity with a similar set of three trials with pictures of big and little animals (i.e., bunny, dog, teddy bear). Each trial was scored on a 3-point scale, with values of 1 (ambiguous or incorrect response on both item and size of object), 2 (correct item but wrong size), or 3 (correct item and correct size). The six task items where children had to point to the little object inside the big object (3 fruit, 3 animal) were averaged to compute the scale score (α = .86). A principal components analysis of the six task items obtained a one component solution (eigenvalue = 3.59) using parallel analyses and Velicer’s MAP tests, as recommended by O’Connor (2000). For 14% of the cases, a second staff member watched the stroop task from the video recording and completed the same set of 6 items. The intraclass correlation between raters for this measure was .83.

Second, children were observed in a gift delay task (Kochanska et al., 2000) to measure their inhibitory control. In this task the interviewer told the child that she had a present that she thought the child would really like, and told the child to sit with their hands over their eyes so that the interviewer could wrap the present. The interviewer instructed the child not to peek and then noisily wrapped the gift. After 1 minute, the interviewer gave the child the wrapped present but instructed the child not to touch the present until she returned with the bow. After 2 minutes, the interviewer returned with the bow and let the child open the present. Ratings of the child’s ability to inhibit impulses were coded by the interviewer after the session, referencing the video recording, with the following two items: “How often did the child touch the gift when interviewer left the room?” (1 [yes, repeatedly] to 3 [no, not at all]); and “The child used distraction strategies” (1 [very true] to 4 [not true]). The item assessing whether the child touched the gift was rescaled 1 to 4 with higher scores indicating greater ability to delay gratification. This rescaling did not change any of the psychometric properties, as the modification retains the same scale as the other variable in the scale so both could be composited and retain equal weighting. Similarly, the item assessing children’s distraction strategies was recoded so that higher scores indicated greater ability to delay gratification. The two items were then averaged to indicate greater ability to delay gratification (ρ = .75). The Spearman-Brown reliability coefficient was used because it is on average less biased than Pearson correlation and has less restrictive assumptions than Cronbach’s alpha (Eisinga, Te Grotenhuis, & Pelzer, 2013). For 11% of the cases, a second staff member watched the gift delay task from the video recording and coded the two items assessing whether the child touched the gift when the interviewer left the room and whether the child used distraction strategies. The intra-class correlation between raters for this measure on the two items (touching the gift and distraction strategies) was .61, which suggests adequate agreement according to Landis and Koch (1977).1

Child externalizing problems

To measure teacher-reported externalizing problems in the classroom, the Externalizing factor from the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used. The TRF is a well-validated measure of child problem behavior and was administered to the primary teacher of study participants at ages 6 and 7. The broad-band externalizing scale comprises the narrow band scales for aggressive behavior and rule-breaking behavior. Internal consistency for the 35-item scale was .95 and .92 at ages 6 and 7, respectively. Data from the two assessments (age 6 and 7) were combined in order to maximize the sample size. A mean of the two scores was used when data were available at both time points (n = 94). Either report was used as the outcome when only data from one assessment were available (n = 131). This approach yielded 225 cases (i.e., based on 173 reports at age 6, 183 reports at age 7). The sample had symptom levels predominantly in the normal range; 9% had ‘sub-clinical’ levels of externalizing problems (T scores between 60 and 63); and 7% of children had ‘clinical’ levels of externalizing problems (T scores greater than 63) according to the CBCL guidelines.

Control Variables

Several control variables were included to ensure that phenomena non-central to the study hypotheses were not significantly affecting the outcome. Sex of toddler was coded 0 for boys and 1 for girls. Openness of adoption, based on aggregated perceived contact across adoptive families and birth mothers at 9 months (Ge et al., 2008) was considered as a control for contact between parties that might confound inferences around genetic and environmental influences on child externalizing problems. Prenatal risk factors assessed in the birth mother’s pregnancy history interview—indices of maternal substance use and toxin exposure during pregnancy, as well as prenatal health complications—were considered as obstetric complications risk and included as covariates because they can confound estimates of genetic and environmental influences (Marceau et al., 2013). Finally, to account for inherited influences on child externalizing problems, three birth mother self-report measures were considered as indicators of birth mother externalizing problems: lifetime alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other drug dependence; delinquency (measured using the Elliot Social Behavior Questionnaire; Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985); and novelty seeking (measured with the novelty seeking subscale of the Temperament Character Inventory; Cloninger, Svrakic, & Przybeck, 1993). For full information on scale construction, refer to Leve et al. (2010).

Results

Data Analytic Strategy

Two sets of analyses were conducted using hierarchical multiple regression. The first set examined the main and joint effects of adoptive mother parenting and child EC on teachers’ reports of school-age externalizing problems. The second set examined the main and joint effects of adoptive father parenting and child EC on teachers’ reports of school-age externalizing problems. There is one regression equation for each parent with 12 predictors (4 covariates, 2 child EC scores, 2 parenting scores for the given parent, and 4 EC × parenting interaction terms). All independent variables were centered and the centered variables were used to create interactions terms. Square transformation was conducted on the adoptive parent warm parenting variable to correct for non-normal distribution; all other variables were normally distributed. Additionally, analyses were conducted without any covariates in the models to guard against the risk of suppressor effects in which relations become more significant only in the presence of other predictors/covariates. Follow-up analyses were performed to examine whether significant findings were robust to the inclusion of the covariates and distinguish between significant associations that were evident with and without the inclusion of covariates. All significant findings remained with the inclusion of the covariates, with no suppressor effects emerging with the addition of covariates. Models with the covariates are reported in the following section.

Descriptive Statistics

The sample sizes, means, standard deviations, and pairwise bivariate correlations for study variables are presented in Table 1. Consistent with the study hypotheses, teachers’ reports of school-age externalizing problems were negatively associated with child EC (for Stroop task r(206)= −.17, p < .05; for gift delay task r(206)= −.12, p < .05) and mothers’ reports of warm parenting (r(200) = −.21, p < .01).

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Variables Used in Regression Analyses.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Birth Mother Externalizing | -- | ||||||||||

| 2. Obstetric Risk | .29** | -- | |||||||||

| 3. Child Gender | −.07 | .01 | -- | ||||||||

| 4. Openness of adoption | .07 | −.06 | −.07 | -- | |||||||

| 5. Adoptive Mother Warm Parenting | .07 | .03 | .02 | −.06 | -- | ||||||

| 6. Adoptive Father Warm Parenting | .01 | −.05 | .14* | −.04 | .23** | -- | |||||

| 7. Adoptive Mother Overreactive Parenting | −.10 | −.03 | .12** | −.06 | −.30** | −.05 | -- | ||||

| 8. Adoptive Father Overreactive Parenting | .04 | .07 | −.03 | −.07 | −.10 | −.27** | .24** | -- | |||

| 9. Child EC (stroop task) | .10 | −.13* | .20** | .20** | −.03 | .05 | .06 | −.06 | -- | ||

| 10. Child EC (gift delay task) | .08 | −.02 | .13* | .14* | .04 | .05 | −.02 | .02 | .03 | -- | |

| 11. Teacher Report of Child Externalizing Problem | −.04 | .02 | −.21** | .03 | −.21** | .08 | .09 | −.02 | −.17* | −.12* | -- |

| Mean | −.00 | 9.60 | .43 | −.02 | 25.93 | 24.98 | 2.10 | 2.09 | 1.82 | 2.04 | 49.68 |

| SD | .72 | 6.65 | .50 | .96 | 2.27 | 2.73 | .60 | .59 | .59 | .86 | 8.61 |

Note. T scores are provided in presenting descriptive statistics for the TRF externalizing, although raw scores were used for testing hypotheses in models to avoid potential age and gender corrections. EC = effortful control.

p < .05.

p < .01

Main and Joint Effects of Adoptive Mother Parenting and Child EC on School-Age Externalizing Problems

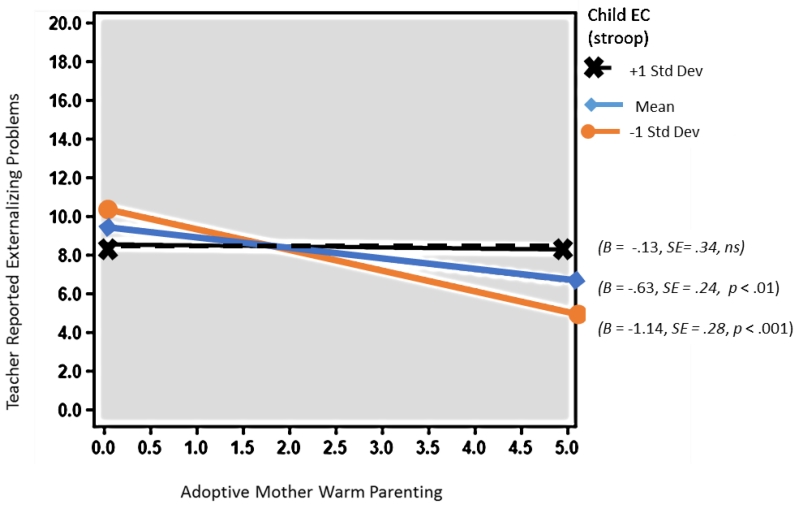

In the first set of analyses, we examined the main and joint effects of child EC (stroop and gift delay task) and adoptive mother parenting (warm and overreactive) on teachers’ reports of school-age externalizing problems. As shown in Table 2, being female (B = –2.02, SE =1.15, p < .01), warm parenting (B = −.60, SE = .25, p < .01), and child EC (stroop task; B = −1.54, SE = 1.01, p < .05; gift delay task: B = −.87, SE= .48, p < .05) were significant predictors of lower levels of teacher reported school-age externalizing problems. However, the main effects of warm parenting and child EC were qualified by significant interactions between warm parenting and child EC, with the stroop task and the gift delay task, in relation to child externalizing problems at school (stroop task; B = .79, SE = .38, p < .05; gift delay task: B = .46, SE = .23, p < .05). To better understand this interaction, the effect of adoptive mother warm parenting on school-age externalizing problems for child EC (stroop task) 1 SD above/below the mean values was calculated and plotted according to procedures outlined by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006). As presented in Figure 1, having an adoptive mother high in warm parenting was associated with lower levels of school-age externalizing problems when levels of child EC (stroop task) were low (B = −1.14, SE = .28, p < .001) and at the mean of child EC (B = −.63, SE = .24, p < .01), but not when they were high (B = −.13, SE = .34, ns). Analysis of the region of significance (see Preacher et al., 2006) indicated that the effect of adoptive mother warm parenting on school-age externalizing problems was significant for levels of child EC (stroop task) less than approximately .13 standard deviations above the mean.

Table 2. Moderating Role of Child EC on the Association between Adoptive Mother Warm Parenting and Teacher-Reported Externalizing Problems.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Variable | B (SE B) |

β | B (SE B) |

β | B (SE B) |

β |

| Adoption openness | .20 (.57) |

.03 | .59 (.57) |

.08 | .50 (.58) |

.06 |

| Obstetric Complications Risk | .01 (.09) |

.00 | −.03 (.10) |

−.03 | −.04 (.09) |

−.03 |

| Birth Parent Externalizing | −.69 (.94) |

−.06 | −.38 (.92) |

−.03 | .39 (.92) |

−.03 |

| Child Gender | −3.44 (1.13) |

−.22** | −2.63 (1.16) |

−.17* | −2.02 (1.15) |

−.13* |

| Child EC (Stroop task) | −.207 (1.00) |

−.15* | −1.54 (1.01) |

−.12* | ||

| Child EC (gift delay task) | .94 (.49) |

−.14* | −.87 (.48) |

−.13* | ||

| Adoptive Mother Warm Parenting | −.69 (.25) |

−. 20 | −.60 (.25) |

−.18* | ||

| Adoptive Mother Overreactive Parenting | .27 (.98) |

.02 | .05 (.99) |

.00 | ||

| Child EC (stroop) × Adoptive Mother Warm Parenting | .79 (.38) |

.16* | ||||

| Child EC (stroop) × Adoptive Mother Overreactive Parenting | 1.04 (1.67) |

.05 | ||||

| Child EC (gift delay) × Adoptive Mother Warm Parenting | .46 (.23) |

.16* | ||||

| Child EC (gift delay) × Adoptive Mother Overreactive Parenting |

−.27 (.93) |

−.02 | ||||

| R 2 | .05* | .08** | .06* | |||

| F for change in R2 | 2.49* | 3.48** | 3.42** | |||

Note. Variables added in each block are presented. EC = effortful control.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Moderating role of child EC (stroop task) on the association between adoptive mother warm parenting and school age externalizing problems. Both the moderator variable and the focal predictor are mean centered. EC = effortful control.

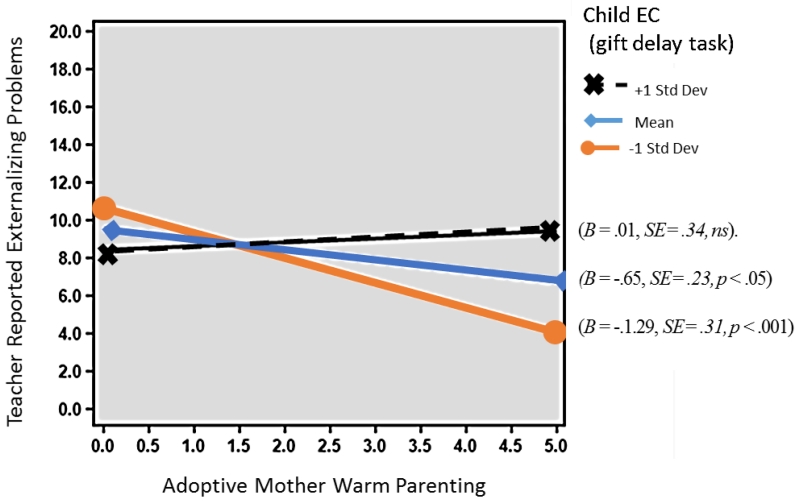

The same pattern was evident when the interaction term between EC (gift delay task) and warm parenting was probed. As shown in Figure 2, adoptive mothers’ warm parenting was associated with lower levels of school-age externalizing problems when levels of child EC were low (B = −.1.29, SE = .31, p < .001) and at the mean (B = −.65, SE = .23, p < .05), but not when they were high (B = .01, SE = .34, ns). Analysis of the region of significance showed that the effect of adoptive mother warm parenting on school-age externalizing problems was significant for levels of child EC (gift delay task) less than approximately .26 standard deviations above the mean.

Figure 2.

Moderating role of child EC (gift delay task) on the association between adoptive mother warm parenting and school age externalizing problems. Both the moderator variable and the focal predictor are mean centered. EC = effortful control.

Main and Joint Effects of Adoptive Father Parenting and Child EC on School-Age Externalizing Problems

In the second set of analyses, we examined the main and joint effects of child EC (stroop and gift delay tasks) and adoptive father parenting (warm and overreactive) on teachers’ reports of school-age externalizing problems. This model was employed to examine similarities and differences between mother–child and father–child relationships. As shown in Table 3, being female (B = –2.94, SE = 1.25, p < .01), and child EC (stroop task; B = −2.50, SE = 1.10, p < .05; gift delay task: B = −1.00, SE = .52, p < .05) were significant predictors of lower levels of teacher reported school-age externalizing problems. There were no significant interactions between child EC (stroop or gift delay task) and father parenting (warm or overreactive parenting) in relation to school-age externalizing problems.

Table 3. Moderating Role of Child EC on the Association between Adoptive Father Warm Parenting and Teacher-Reported Externalizing Problems.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Variable | B (SE B) |

β | B (SE B) |

β | B (SE B) |

β |

| Adoption openness | .06 (.61) |

.01 | .54 (.63) |

.07 | .55 (.63) |

.07 |

| Obstetric Complications Risk | .01 (.10) |

.01 | −.02 (.10) |

−.01 | −.02 (.10) |

−.02 |

| Birth Parent Externalizing | −.82 (.97) |

−.07 | .55 (.97) |

−.04 | −.46 (.97) |

−.04 |

| Child Gender | −3.78 (1.17) |

− .24** |

3.05 (1.23) |

−.19* | −2.94 (1.25) |

−.19* |

| Child EC (Stroop task) | −2.29 (1.08) |

−.17* | −2.50 (1.10) |

−.18* | ||

| Child EC (gift delay task) | −.96 (.52) |

−.14* | −1.00 (.52) |

−.14* | ||

| Adoptive Father Warm Parenting | .27 (.22) |

.10 | −.18 (1.05) |

.10 | ||

| Adoptive Father Overreactive Parenting | −.14 (1.05) |

−.01 | −.18 (1.05) |

−.01 | ||

| Child EC (stroop) × Adoptive Father Warm Parenting | .76 (.41) |

.14+ | ||||

| Child EC (stroop) × Adoptive Father Overreactive Parenting |

.00 (1.60) |

.00 | ||||

| Child EC (gift delay) × Adoptive Father Warm Parenting | .14 (.20) |

.05 | ||||

| Child EC (gift delay) × Adoptive Father Overreactive Parenting |

.13 (.90) |

.04 | ||||

| R 2 | .06* | .05* | .02 | |||

| F for change in R2 | 2.81* | 2.60* | 2.05* | |||

Note. Variables added in each block are presented. EC = effortful control.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Discussion

The current investigation used an adoption design to examine links between adoptive mother and father parenting, child EC, and school-age externalizing problems. This study addresses limitations of previous studies by investigating the effect of parenting behavior on externalizing problems, when effects due to genes shared among biologically-related family members are removed. In accord with our hypothesis, higher levels of warm parenting were associated with lower levels of externalizing problems, and interactions between EC and warm parenting were found in the development of school-age externalizing problems. Importantly, the current investigation provides support for the notion that parenting behavior assessed in the toddler period, when effects due to genes shared among biologically-related family members are removed, is associated with children’s subsequent school-age externalizing problem behavior.

This study advances a core objective outlined by Rutter et al. (2001) in testing hypotheses relating to environmental influences on children’s psychological outcomes. In typical studies of biological parent(s) and their child any associations between parenting and measures of child outcome may be subject to the confounding effects of passive rGE. Getting an accurate account of which of the associations between parent and child phenotypes are confounded with inherited influences and which are not is crucial because manipulating the rearing environment may provide a mechanism through which parents and practitioners can have a positive impact on the development of children. In the current analyses there was no inherited influence of birth mother externalizing behavior on child externalizing behavior. Two possible reasons for the non-significant association between birth mother and child externalizing problems are that genetic effects may become stronger with age (Jacobson, Prescott, & Kendler, 2002) and there may be no direct genetic effect at this age, but genetic factors may enhance sensitivity to adverse environmental factors (Rhoades et al., 2011).

Moderating Role of Child EC on the Association between Adoptive Mother Warm Parenting and Externalizing Problems

Consistent with our hypothesis, findings from this study documented that higher levels of adoptive mother warm parenting at 27 months were significantly associated with lower levels of teacher-reported externalizing problems at ages 6-7. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that parental warmth or positivity is associated with fewer externalizing problems, involving a range of cultural and socioeconomic groups and using a variety of research methods (Chen, Liu, & Li, 2000; Harrist & Waugh, 2002). However, the main effects of warm parenting and child effortful control were qualified by significant interactions between warm parenting and child effortful control. Results indicated that child EC moderated the associations between adoptive mother warm parenting and teacher-reported school-age externalizing problems. This finding suggests that maternal warmth serves as a protective factor against the risk for externalizing problems for children with low levels of EC. The present work can be interpreted within a vantage sensitivity framework (Pluess & Belsky, 2013). Vantage sensitivity represents the positive end, or the “bright” side of differential susceptibility, where increases in the level of functioning are manifested by individuals endowed with specific endogenous characteristics that render them more sensitive to exposure to high-quality environments. On this latter view, the presence of these specific sensitivity traits constitute an advantage with respect to the development (or production) of favorable outcomes in the presence of ecological contexts that provide adequate resources and support. In sum, the present work provides evidence that the quality of parenting employed by parents of children with low levels of EC can affect their future development.

Moderating role of Child EC on the Association between Adoptive Mother Overreactive Parenting and Externalizing Problems

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find a significant positive association between overreactive parenting and child externalizing problems or an interaction between EC and overreactive parenting at 27 months and school-age externalizing problems. The non-significant main effect of overreactive parenting is inconsistent with previous research that has consistently documented links between overreactive parenting and high levels of externalizing problems during early childhood and the early school-age years (Campbell et al., 2000; Maccoby, 2000; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994; Shaw et al., 2003). However, the majority of these studies involve biologically related family members, thereby limiting understanding of the role of genetic and/or environmental underpinnings of parenting on child psychopathology. Similarly, a possible explanation for the null interaction findings is that prior studies that demonstrated moderating effects of attentional skills and regulatory capacity were conducted with older children and adolescents, whereas effortful control was measured during toddlerhood in the current study (Henry, Caspi, Moffitt, & Silva, 1996; Wills, Sandy, Yaeger, & Shinar, 2001). Although effortful control is relatively stable in the early years (Kochanska et al., 2000) and thus levels of toddler effortful control and school-age effortful control would be expected to show moderate stability, a significant moderating role of effortful control might have been more evident if measured during the school-age period when children were coping with contextual demands such as sitting still, attending to instructional materials, and ignoring distracting stimuli.

Direct Associations between Adoptive Father Warm Parenting and Externalizing Problems

Another important contribution of this study was the examination of the effect of adoptive father warm parenting on child externalizing problems. Contrary to the expectations, adoptive father warm parenting was not directly related to school-age externalizing problems. Prior research shows that, compared to mothers, fathers tend to spend less time with young children, even in dual-earner families (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004), and often have different expectations for their roles as parents (Moon & Hoffman, 2008). Differences in fathers’ level of involvement, roles, and expectations for parenthood may explain the lack of association between father warm parenting and child externalizing problems.

Effortful Control: A Multidimensional Construct

An important methodological issue observed in this study is that the two validated measures of EC were not significantly related to one other. This is consistent with prior studies that have examined the structure of EC in young children and found that multiple factors emerge when factor analyses of EC tasks are conducted (Murray & Kochanska, 2002). It was surprising to find that the two tasks putatively measuring different facets of EC were essentially unrelated to each other. Other studies have found modest correlations between different indices of EC (Kim, Nordling, Yoon, Boldt, & Kochanska, 2013) and in some cases tasks increased in their magnitude of association over time (Kochanska et al., 2000). For example, Kochanska et al. (2000) found that at 22 months, Cronbach’s alpha was relatively modest between different EC tasks (.42); the average item-total correlation was .27. However, at 33 months, the alpha was .77, and the average item-total correlation was .42. As we only measured EC at one time point, we were unable to assess whether coherence between EC measures increased. It may be that the coherence was weak because too few tasks were coded or because the assessed capacities are just beginning to be organized into a cohesive system. Although the two indices of EC were not highly correlated, it was notable how in correlations and regression both indices of EC were comparably and uniquely related to externalizing symptoms. Furthermore, the evidence that both measures of EC related to externalizing symptoms suggests that both attentional and inhibitory control are implicated in the emergence of psychopathology. Our results differ from some (but not all) theory and empirical research that has found that “hot” EC function (delay-of-gratification tasks) and more abstract “cool” EC functions (Stroop-like tasks) differentially predict children’s behavior problems and academic performance (Kim, Nordling, Yoon, Boldt, & Kochanska, 2013).

Limitations

Although the current study has a number of important strengths, there are several limitations that need to be noted. First, a limited number of items were used to assess effortful control for the gift delay task. While the use of multiple, heterogeneous indicators is preferable because it enhances construct validity and reliability, other studies have also used single or two items to assess effortful control in a gift delay task (Carlson et al., 2004; Mulder, Hoofs, Verhagen, van der Veen, & Leseman, 2014; Spinrad, Eisenberg, & Gaertner, 2007). Combined with the fairly wide use of this task in prior studies of toddlers, the face validity of the task, and the relatively high Spearman-Brown correlation between the two items used, the measure was retained (Carlson et al., 2004; Kochanska et al., 2000). Second, the findings reported here may or may not be representative of what might be expected with more heterogeneous samples, reflecting a wider range of individual difference characteristics. Additionally, it is unclear whether the findings from this study would be generalizable to clinical populations because most of the sample had TRF scores in the normative range. Most of the children included in this sample do not have clinically meaningful levels of problem behavior. However, based on birth mother characteristics (genetic risk) and prenatal risk exposure, these children are considered at-risk for developing higher levels of problems. Therefore, the generalizability of findings to high-risk home environments and more ethnically diverse samples needs to be documented before stronger conclusions can be drawn.

Second, the current paper only examines unidirectional pathways from parenting to child behavior. However, the literature on parenting is replete with theoretical and empirical evidence of child effects on parents (Bell, 1968; Bell & Chapman, 1977). Belsky’s (1984) landmark paper on the determinants of parenting provides a foundation for reciprocal models of parent-child interaction by positing that characteristics of both the parent and child contribute to adaptive and dysfunctional parenting. Future studies should account for early levels of externalizing behavior to examine prospective change in externalizing behavior as a function of parenting and/or consider bidirectional relations between child externalizing behavior and parenting over time. It is also conceivable that an evocative rGE remains as an explanatory mechanism. Evocative rGE for parenting occurs when inherited characteristics of the child affect their parents’ behavior towards them (Dunn, Plomin, & Daniels, 1986; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). It is conceivable, for example, that genetic influences on children’s EC during toddlerhood influenced our measures of warm and overreactive parenting at age 27-months.

This study used parent-report, questionnaire-based measures to assess parenting. This approach is associated with certain limitations that might bias and inflate associations, notably parent’s expectations, their negative attributions about the child, and their low mood (Gardner, 2000). Ideally self-reports of parenting would have been corroborated by direct observations of parent–child interactions that were coded for overreactive and warm parenting. Observational techniques can provide a microscopic view of how behavior unfolds over time, and how it is influenced by social conditions, including the behavioral triggers and reactions of others (Gardner, 2000). It should be noted that although some studies find significant relations between observational and self-report measures of the same constructs (Arnold et al., 1993; Webster-Stratton, 1998), in many cases studies find modest (Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996) or low levels of convergence (correlations of the order of r = .3 or so). This suggests a good deal of unique information may be provided by both sources. Furthermore, the constructs used to measure birth parent externalizing problems (self-worth, depression, anxiety, and substance use) were self-report measures, which also may be susceptible to reporting bias.

Future Directions and Clinical Implications

This study corroborated a consistent finding in the literature that some forms of parenting are important to the development of childhood externalizing problems and thus is an important area for prevention and intervention. Importantly, warm caregiving practices of adoptive parents were directly protective against later child externalizing problems, corroborating decades of research that could not unpack genetic from environmental influence when examining associations between parenting and child problem behavior. If the current findings could be shown to be generalizable to at-risk populations, it would suggest that prevention efforts and interventions directed at warm parenting are a promising avenue for improving child behavioral trajectories (Smith, Dishion, Shaw, & Wilson, 2013). Additional work in this area could refine interventions in terms of targeting specific parenting practices aimed at preventing the development of maladaptive outcomes.

Additionally, differences between girls and boys in the development of externalizing problems and EC warrant attention to gender as a moderator of environmental risks to development (Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, & Van Hulle, 2006). Girls tend to have more advanced EC and fewer externalizing problems than boys in early childhood (Deater-Deckard et al., 1998; Olson et al., 2005). Further, we know little of how the interaction between parenting and child EC contributes to gender differences in externalizing problems. It is possible that girls’ higher self-regulation relative to boys protects them from contextual risk factors for externalizing problems. For these reasons, child gender should be examined in future analyses to test for differences in the effects of parenting and child EC on externalizing behavior.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grant R01 HD042608 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI Years 1–5: David Reiss, MD; PI Years 6–10: Leslie Leve, PhD). The current paper was also supported by a Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1247842) from NSF to the first author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

We would like to thank the birth and adoptive parents who participated in this study and the adoption agency staff members who helped with the recruitment of study participants.

Footnotes

A prior paper used a 3-item version (Leve et al., 2014); a 2-item version was used here due to reviewer feedback and improved reliability

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was conducted in compliance with the requirements of the Institutional Research Ethics Boards, and informed consent/ assent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Julia D. Reuben, University of Pittsburgh

Daniel S. Shaw, University of Pittsburgh

Jenae M. Neiderhiser, The Pennsylvania State University

Misaki N. Natsuaki, University of California, Riverside

David Reiss, Yale University.

Leslie D. Leve, University of Oregon

References

- Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. University of vermont. Research Center for Children, Youth & Families, Burlington, VT. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar B, Sroufe L, Egeland B, Carlson E. Distinguishing the early-onset/persistent and adolescence-onset antisocial behavior types: From birth to 16 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:109–132. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DS, O’Leary SG, Wolff LS, Acker MM. The parenting scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Rijsdijk FV, Jaffee SR, Measelle JR. Strong genetic effects on cross-situational antisocial behaviour among 5-year-old children according to mothers, teachers, examiner-observers, and twins’ self-reports. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:832–848. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Pettit GS. Temperament, parenting, and socialization. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of socialization: Theory and research. Guilford Press; New York, NY, US: 2007. pp. 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Schermerhorn AC, Petersen IT. Temperament concepts in developmental psychopathology. In: Lewis M, Rudolph KD, editors. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. Springer; US: 2014. pp. 311–329. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeldt DL, Rhee SH, Dilalla LF, Mullineaux PY, Schulz-Heik RJ, Corley RP, Hewitt JK. The association between positive parenting and externalizing behavior. Infant Child Development. 2012;21:85–106. doi: 10.1002/icd.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:271–301. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Are there meaningful etiological differences within antisocial behavior? Results of a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:163–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:467–488. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, Mandell DJ, Williams L. Executive function and theory of mind: Stability and prediction from ages 2 to 3. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1105–1122. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, Sexton HR. Child effortful control as a mediator of parenting practices on externalizing behavior: Evidence for a sex-differentiated pathway across the transition from preschool to school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9437-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Liu M, Li D. Parental warmth, control, and indulgence and their relations to adjustment in chinese children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:401–419. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:975–990. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Physical discipline among african american and european american mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1065. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Multiple risk factors in the development of externalizing behavior problems: Group and individual differences. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:469–493. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Plomin R. An adoption study of the etiology of teacher and parent reports of externalizing behavior problems in middle childhood. Child Development. 1999;70:144–154. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKlyen M, Speltz M, Greenberg M. Fathering and early onset conduct problems: Positive and negative parenting, father–son attachment, and the marital context. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:3–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1021844214633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the united states (2005) DIANE Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Workman E, Cole PM, Weissbrod C, Kendziora KT, Zahn-Waxler C. Prediction of externalizing behavior problems from early to middle childhood: The role of parental socialization and emotion expression. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:23–45. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400001024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T. The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptive processes. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JF, Plomin R, Daniels D. Consistency and change in mothers’ behavior toward young siblings. Child Development. 1986;57:348–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:136–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Reiser M. Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development. 1999;70:513–534. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Losoya SH, Valiente C, Shepard SA. The relations of problem behavior status to children’s negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: Concurrent relations and prediction of change. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:193–211. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Cumberland A, Shepard SA, Thompson M. The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency and adjustment. Child Development. 2004;75:25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Liew J, Zhou Q, Losoya SH, Cumberland A. Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisinga R, Te Grotenhuis M, Pelzer B. The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, cronbach, or spearman-brown? International Journal of Public Health. 2013;58:637–642. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Hyde JS, Goldsmith HH, Van Hulle CA. Gender differences in temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:33–72. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F. The quality of joint activity between mothers and their children with behaviour problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:935–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb02303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F. Methodological issues in the direct observation of parent-child interaction: Do observational findings reflect the natural behavior of participants? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:185–198. doi: 10.1023/a:1009503409699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Burton J, Supplee L. Randomized prevention trial for early conduct problems: Effects on proactive parenting and links to toddler disruptive behavior. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:398. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge XJ, Natsuaki MN, Martin DM, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Reiss D. Bridging the divide: Openness in adoption and postadoption psychosocial adjustment among birth and adoptive parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:529–540. doi: 10.1037/a0012817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrist AW, Waugh RM. Dyadic synchrony: Its structure and function in children’s development. Developmental Review. 2002;22:555–592. [Google Scholar]

- Henry B, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Temperamental and familial predictors of violent and nonviolent criminal convictions: Age 3 to age 18. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:614–623. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra MB, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Child and adolescent problems predict dsm-iv disorders in adulthood: A 14-year follow-up of a dutch epidemiological sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:182–189. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KC, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Sex differences in the genetic and environmental influences on the development of antisocial behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:395–416. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiff CJ, Lengua LJ, Zalewski M. Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:251–301. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Nordling JK, Yoon JE, Boldt LJ, Kochanska G. Effortful control in “hot” and “cool” tasks differentially predicts children’s behavior problems and academic performance. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:43–56. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindlon DJ, Tremblay RE, Mezzacappa E, Earls F, Laurent D, Schaal B. Longitudinal patterns of heart rate and fighting behavior in 9- through 12-year-old boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:371–377. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Toward a synthesis of parental socialization and child temperament in early development of conscience. Child Development. 1993;64:325–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, Harlan ET. Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:220–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME. The role of the father in child development. 4th ed. Wiley; Hoboken, N.J.: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Kerr DC, Shaw D, Ge X, Neiderhiser JM, Scaramella LV, Reiss D. Infant pathways to externalizing behavior: Evidence of genotype × environment interaction. Child Development. 2010;81:340–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01398.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ganiban J, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D. The early growth and development study: A prospective adoption study from birth through middle childhood. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2013;16:412–423. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, Scaramella LV, Ge X, Reiss D. Negative emotionality and externalizing problems in toddlerhood: Overreactive parenting as a moderator of genetic influences. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:167–179. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Parenting and its effects on children: On reading and misreading behavior genetics. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2000;51:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Ram N, Neiderhiser JM, Laurent HK, Shaw DS, Fisher P, Leve LD. Disentangling the effects of genetic, prenatal and parenting influences on children’s cortisol variability. Stress. 2013;16:607–615. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2013.825766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Colletti C, Rakow A, Jones DJ, Forehand R. Parenting and child externalizing behaviors: Are the associations specific or diffuse? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The iowa family interaction rating scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig JK, Lindhal JM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ, US: 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Moon M, Hoffman CD. Mothers’ and fathers’ differential expectancies and behaviors: Parent × child gender effects. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2008;169:261–279. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.169.3.261-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Sessa FM, Avenevoli S, Essex MJ. Temperamental vulnerability and negative parenting as interacting predictors of child adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:461–471. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder H, Hoofs H, Verhagen J, van der Veen I, Leseman PPM. Psychometric properties and convergent and predictive validity of an executive function test battery for two-year-olds. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014:733. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KT, Kochanska G. Effortful control: Factor structure and relation to externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:503–514. doi: 10.1023/a:1019821031523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Goldsmith HH, Sachek J. Temperament and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The development of a multiple pathway model. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:42–53. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor BP. Spss and sas programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and velicer’s map test. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2000;32:396–402. doi: 10.3758/bf03200807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary SG, Slep AM, Reid MJ. A longitudinal study of mothers’ overreactive discipline and toddlers’ externalizing behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:331–341. doi: 10.1023/a:1021919716586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Caspi A. Female and male antisocial trajectories: From childhood origins to adult outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:673–716. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, Kerr DC, Lopez NL, Wellman HM. Developmental foundations of externalizing problems in young children: The role of effortful control. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:25–45. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Compas BE. The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: Make room for daddy. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:387–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Masciadrelli BP. The role of the father in child development. 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, US: 2004. Paternal involvement by u.S. Residential fathers: Levels, sources, and consequences; pp. 222–271. [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC, Knopik VS, Neiderheiser J. Behavioral genetics. revised ed. Palgrave Macmillan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC, Loehlin JC. Genotype-environment interaction and correlation in the analysis of human behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1977;84:309–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluess M, Belsky J. Vantage sensitivity: Individual differences in response to positive experiences. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139:901. doi: 10.1037/a0030196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Price TS, Jaffee SR. Effects of the family environment: Gene-environment interaction and passive gene-environment correlation. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:305–315. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Waldman ID. Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:490–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades KA, Leve LD, Harold GT, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Reiss D. Longitudinal pathways from marital hostility to child anger during toddlerhood: Genetic susceptibility and indirect effects via harsh parenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:282–291. doi: 10.1037/a0022886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. In: Temperament. 5 ed. Eisenberg N, editor. Vol. 3. Wiley; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Rueda MR. The development of effortful control. In: Mayr U, Awh E, Keele SW, editors. Developing individuality in the human brain: A tribute to michael i. Posner. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, US: 2005. pp. 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, Weisz JR. Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:55–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Pickles A, Murray R, Eaves L. Testing hypotheses on specific environmental causal effects on behavior. Psychol Bulletin. 2001;127:291–324. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Leve LD. Clarifying parent-child reciprocities during early childhood: The early childhood coercion model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7:89–107. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000030287.13160.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, McCartney K. How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype greater than environment effects. Child Development. 1983;54:424–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1983.tb03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DS. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN. Indirect effects of fidelity to the family check-up on changes in parenting and early childhood problem behaviors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:962–974. doi: 10.1037/a0033950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Gaertner BM. Measures of effortful regulation for young children. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2007;28:606–626. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL, McMahon RJ, Lengua LJ, Conduct Problems Prevention Research, G. Parenting practices and child disruptive behavior problems in early elementary school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:17–29. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE, Pihl RO, Vitaro F, Dobkin PL. Predicting early onset of male antisocial behavior from preschool behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:732–739. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950090064009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst F, Koot H, Van der Ende J. Differential predictive value of parents’ and teachers’ reports of children’s problem behaviors: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:531–546. doi: 10.1007/BF02168936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall G, Arnold S. How involved is involved fathering?: An exploration of the contemporary culture of fatherhood. Gender & Society. 2007;21:508–527. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Preventing conduct problems in head start children: Strengthening parenting competencies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:715. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger A, Shinar O. Family risk factors and adolescent substance use: Moderation effects for temperament dimensions. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:283–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]