Abstract

Aim

To compare radiological and pathological changes and test the adjunct efficacy of Sorafenib to Y90 as a bridge to transplantation in HCC.

Methods

15 patients with 16 HCC lesions randomized to Y90 without (Group A, n=9) or with Sorafenib (Group B, n=7). Size (WHO, RECIST), enhancement (EASL, mRECIST) and diffusion-weighted imaging criteria (ADC) measurements were obtained at baseline, 1 and every 3 months after treatment until transplantation. Percentage necrosis in explanted tumors was correlated with imaging findings.

Results

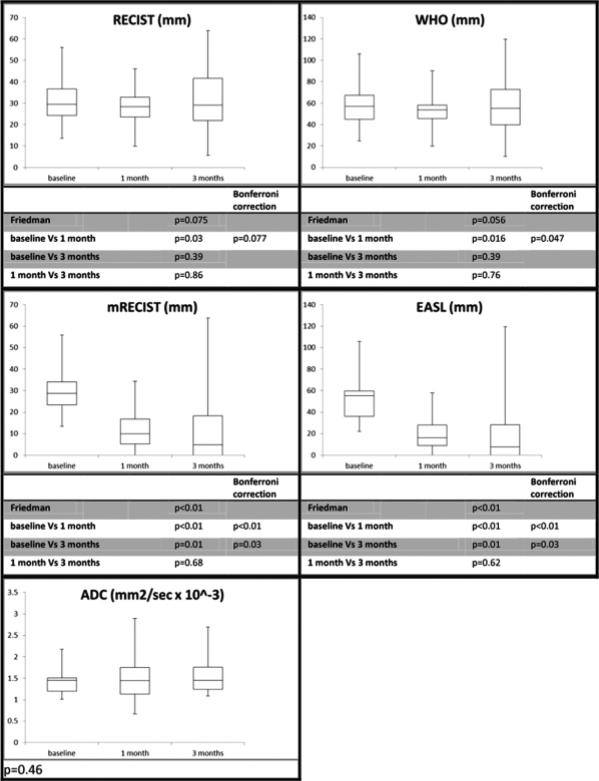

100%, 50-99% and <50% pathological necrosis was observed in 6 (67%), 1 (11%) and 2 (22%) tumors in Group A and 3 (42%), 2 (28%) and 2 (28%) in Group B, respectively (p=0.81). While ADC (p=0.46) did not change after treatment, WHO (p=0.06) and RECIST (p=0.08) response at 1 month failed to reach significance, but significant responses by EASL (p<0.01/0.03) and mRECIST (p<0.01/0.03) at 1 and 3 months were observed. Response was equivalent by EASL or mRECIST. No difference in response rates were observed between groups A and B at 1 and 3 months by WHO, RECIST, EASL, mRECIST or ADC measurements. Despite failing to reach significance, smaller baseline size was associated with CPN (RECIST: p=0.07; WHO: p=0.05). However, a cut-off size of 35 mm was predictive of CPN (p=0.005). CPN could not be predicted by WHO (p=0.25 and 0.62), RECIST (p=0.35 and 0.54), EASL (p=0.49 and 0.46), mRECIST (p=0.49 and 0.60) or ADC (p=0.86 and 0.93).

Conclusion

The adjunct of Sorafenib did not augment radiological or pathological response to Y90 therapy for HCC. Equivalent significant reduction in enhancement at 1 and 3 months by EASL/mRECIST were noted. Neither EASL nor mRECIST could reliably predict CPN.

Keywords: imaging, hepatocellular carcinoma, mRECIST, RECIST, pathology analysis

INTRODUCTION

The development of surrogate markers for locoregional therapies (LRT) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is desirable in order to improve treatment planning and accelerate design/endpoints in clinical trials. Before validation, early imaging surrogate markers face different challenges, including methodological considerations, reproducibility, accuracy to detect real treatment response, and potentially most importantly, the detection of a survival benefit. In comparison with survival, surrogate endpoints (time-to-progression (TTP), progression-free survival) offer the advantage of potentially less confounding effect by concomitant liver (i.e. cirrhosis, fibrosis) or systemic diseases, previous or subsequent locoregional or systemic treatment.(1)

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines (2011) advocate the use of enhancing tissue to assess imaging response of HCC.(2) Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) were devised keeping this concept in mind and are now being proposed as standard methodology of radiological response in HCC.(3) However, few radiological-pathological studies support these criteria; our research group has previously highlighted the importance of these important correlative concepts for both chemoembolization and radioembolization.(4-6) Uni/bi-dimensional measurements of the entire treated tumor (RECIST, World Health Organization (WHO) criteria), are often criticized given their lack of correlation with viable tumor. Emerging functional imaging parameters also exist; diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), representing the motion restriction of free water molecules, is one of the most commonly discussed techniques.(7)

The aim of this study was to compare radiological and pathological changes and test the adjunct efficacy of Sorafenib to Y90 as a bridge to transplantation in HCC. We tested WHO, EASL, RECIST, mRECIST and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values (DWI parameter) as surrogate markers of complete pathological response after randomization to Yttrium-90 radioembolization (Y90) with or without Sorafenib.

METHODS

Patient Sample

This is a detailed imaging analysis from a prospective, randomized study of Y90 radioembolization +/− Sorafenib in HCC patients being bridged to orthotopic liver transplant (OLT). They were randomized 1:1 to Y90 alone (Group A) or in combination with Sorafenib (Group B). The trial was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board, compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and registered (NCT00846131). The clinical effects (adverse events, tolerability, dose reductions) of combining Y90 with Sorafenib are beyond the scope of this imaging analysis are being reported in a separate manuscript focused on clinical outcomes.

Inclusion criteria for the study included HCC confirmed by AASLD guidelines, Child-Pugh score ≤B8, and candidates for OLT (up to UCSF criteria)(2). Patients with performance status >2, metastatic disease, tumor-related portal vein thrombosis (PVT) and/or biological or clinical abnormality contraindicating Sorafenib or radioembolization were not study candidates. By protocol, patients receiving >2 Y90 treatments were withdrawn from the analysis. Despite being classified as advanced HCC by Barcelona staging (BCLC), patients with performance status >0 but with imaging findings of BCLC A were still considered for transplantation.

Between February 2009 and October 2012, 23 patients (Group A: N=12, Group B: N=11) were enrolled in the study (Study flow chart). Two did not receive therapy: one patient from Group A did not have confirmed angiographic hypervascularity at angiography (despite meeting diagnostic criteria), with a subsequent biopsy being negative for malignancy, and 1 patient from Group B died prior to treatment (ruptured HCC). One patient from Group A withdrew consent; that patient was treated off study with Y90 followed by OLT. The 20 remaining patients comprise the intention-to-treat patient sample (Group A: N=10, Group B: N=10). The study was officially closed on February 7, 2013 when the last remaining patient in Group A died of cardiac causes while awaiting transplantation.

Y90 procedure

Radioembolization treatment was preceded by a simulation procedure during which 99Tc-macroaggregated albumin was injected into the hepatic arterial vasculature simulating Y90 microspheres distribution in order to estimate the degree of extrahepatic deposition. Coiling of extrahepatic arteries was performed when required to avoid inadvertent deposition. Glass microspheres loaded with 90Yttrium (TheraSphere, Nordion, Canada) were used in this study per standard methodology. Patients were observed for 2 hours (arterial closure device) and subsequently discharged.(8-11)

Sorafenib Treatment

For Group B, Sorafenib 400 mg (2 × 200 mg tablets) was administered orally, initially twice daily (total 800 mg daily/ 4 tablets) before Y90 (median: 20 days, range: 13-35 days). Dose was adjusted per guidelines and Sorafenib treatment never exceeded 12 months. Sorafenib was stopped when imminent transplantation (#1 on transplant list) was expected according to patient's model for end-stage liver disease score. Detailed reporting of adverse events combining Y90 and Sorafenib will be reported elsewhere; in brief, no unexpected toxicities combining Y90/Sorafenib were noted.

Imaging response assessment

All radiological assessment was performed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). One patient in group B who had 2 Y90 sessions, and 2 patients who had 3 Y90 procedures (1 patient in group A and 1 patient in group B) were not transplanted. One patient who had 2 Y90 procedures and chemoembolization in group B was excluded. Eight and 7 patients in groups A and B respectively were transplanted. Consequently, we performed our radiological-pathological study on 15 patients (Group A: N=8; Group B: N=7) for a tumor-by-tumor analysis on 16 HCC lesions (Study flow chart).

MRI protocol included gradient echo T1-weighted fat suppressed (T1 GRE) sequences before and after intravenous injection of Gadolinium (Gd) agent, turbo spin-echo T2-weighted (T2 TSE) sequences and Multi shot PROPELLER Diffusion weighted sequences as described extensively in Supplementary Table 1. Measurements were repeated at 1 and 3 months follow-up MRI scans post Y90 and on all following MRI scans until OLT. In order to evaluate the possible adjunct efficacy of Sorafenib over Y90, tumor response after Y90 was compared to the pre-Y90 MRI scans for both groups.

We measured all treated lesions on arterial phase of post-Gd T1 GRE dynamic sequences according to the WHO and RECIST criteria, respectively measuring the percentage (%) of change in the sum of the maximal bi-dimensional perpendicular diameters and the maximal uni-dimensional diameter, including viable and non-enhancing areas within the tumor, and EASL and mRECIST criteria, respectively measuring the percentage (%) of change in the sum of the maximal bi-dimensional diameters and the maximal uni-dimensional diameter, including only enhancing portion of the tumor. For these response criteria, radiologic interpretation was classified as Complete Response (CR), Partial Response (PR), Stable Disease (SD) or Progressive Disease (PD) according to cut-offs defined in Supplementary Table 2.

As a functional imaging parameter, ADC values were calculated for all treated tumors using the same methodology. On the corresponding post-Gd T1-GRE sequence for the selection of the image level, a circular Region of Interest (ROI) was positioned in the enhancing portion of the tumors (presumably viable) or in the center of the lesion if no viable tumor was identified. A similar ROI was then transferred at the same position on the low b (s/mm) (b 0 or b 50) and high b (b 400 or b 500) sequences and the mean ADC values (mm2/s) were calculated using the following formula:

Arbitrarily, we imposed a minimal size of 1.00 cm2 in order to minimize the error due to low number of voxels included in the ROI sample, and hence minimize the random distribution of our measurements. According to the ADC change of tumors reported in different studies following Sorafenib or Y90, a response (R) was considered as an increase in ADC values of 5% or more and a non-response (NR) as a less than 5% increase in ADC values compared to the appropriate baseline measurement.(12, 13)

Finally, we decided to perform a Subjective response assessment. Three investigators (MV, FHM, RS) independently analyzed the pre/post-Gd T1 GRE dynamic MRI sequences, estimated the percentage non-enhancing tumor, considering these radiological pattern as necrotic tissue and classified subjectively tumor response as CR (no enhancement), PR (>50% but not 100%), SD (between PR and PD) or PD (worsening enhancement) at 1 and 3 months after Y90 treatment for every treated tumor, compared to baseline imaging, without knowledge of the final pathology report. One of them (FHM) also used DWI sequences in borderline cases.

Pathologic findings on explant

Explanted livers were analyzed by surgical pathology in our institution, with sectioning of liver tissue at 0.5-1 cm. Pathological response was classified as 100% complete pathological necrosis (CPN), 50-99% or <50% necrosis per our previous description.(4-6)

Statistical Analysis

All data were summarized using appropriate descriptive statistics (count and frequency for categorical variables, median and range for continuous variables). Uni/multivariate analysis using Mann Whitney U test, Student's t test, chi-square test or Fischer exact test were used where appropriate to compare the radiological parameters between the groups (Group A vs Group B, CPN vs non-CPN) at baseline to identify any potential cofounders, and after Y90. Scatter graphics representing the percentage of change in WHO, RECIST, EASL, mRECIST and ADC measurements for group A and B were built, considering 1, 3 months post-Y90 and all subsequent imaging follow-up until OLT. Whisker box plots showing median, range and interquartile values, as well as ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) by Friedman 2-tailed test and Wilcoxon test were used to demonstrate 1 and 3 months post-Y90 changes, controlling for baseline values, in WHO, RECIST, EASL, mRECIST and ADC values. Bonferroni correction was applied if significant p-values were observed when multiple hypotheses were tested for the same populations. Tumor-by-tumor radiological and pathological response classification was represented by summary table and graphical methods. For all tests, a p-value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using MedCalc software (Mariakerke, Belgium).

RESULTS

Patient Sample

Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. Median age was 57 years. One patient in group B presented with bilobar disease (2 lesions in segment 6, 1 in segment 4a) and was classified United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) stage T3. The groups were otherwise well-balanced.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Variable | Y90 alone (n=8) | Y90 + Sorafenib (n=7) | Total (n=15) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Median | 59 | 56 | 57 | 0.30 |

| Range | 54-67 | 49-62 | 49-67 | ||

| Gender | Male | 5 | 5 | 10 | 1.0 |

| Female | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 5 | 5 | 10 | 1.0 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| African-American | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Etiology | HCV | 5 | 5 | 10 | 1.0 |

| Alcohol | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| NASH | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Alcohol + NASH | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| PBC | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cryptogenic | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Method of Diagnosis | Imaging | 5 | 6 | 11 | 1.0 |

| Biopsy | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Baseline AFP (ng/mL) | Median | 13.2 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 0.60 |

| Range | 1.5-484.6 | 4.5-62.8 | 1.5-484.6 | ||

| ECOG | 0 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 1.0 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Child-Pugh | A | 6 | 5 | 11 | 1.0 |

| B | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| BCLC | A | 4 | 5 | 9 | 1.0 |

| B | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| C | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| Portal Hypertension | Absent | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.47 |

| Present | 8 | 6 | 14 | ||

| Tumor distribution | Unilobar | 8 | 6 | 14 | 1.0 |

| Bilobar | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Multiplicity | Solitary | 8 | 6 | 14 | 0.47 |

| Multifocal | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| UNOS stage | T1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.20 |

| T2 | 8 | 5 | 13 | ||

| T3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Imaging Follow-up

Patients from Group B (n=7) underwent a pre-Sorafenib MRI scan, with a maximum of 32 days before initiation of Sorafenib (median 18; range 8-32) and a maximum of 53 days before Y90 (median 42; range 21-53).

The median time from baseline MRI to Y90 procedure for Group A was 18 days (range: 14-42). Seven of the 8 patients in Group B had baseline MRI scan on the day of Y90 treatment immediately prior to the procedure, translating into a median time from imaging to Y90 of 0 days. For both groups, the pre-Y90 MRI scan served as the baseline.

Median time from last MRI scan to transplant was 25 days (range 5-93). Findings on the last pre-OLT scan were consistent with the 3 month scan for all 16 lesions.

Pathology findings

CPN, 50-99% and <50% necrosis was observed in 6 (67%), 1 (11%) and 2 (22%) tumors in Group A and 3 (42%), 2 (28%) and 2 (28%) in Group B, respectively (p=0.41) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary radiological classification at 1 and 3 months with pathological results

| Anatomic Criteria | Functional Criteria | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECIST | WHO | mRECIST | EASL | Subjective | ADC | ||||

| FM | MV | RS | |||||||

| 1 month (n=16) | |||||||||

| CR | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 3 | R* | 9 |

| PR | 1 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 8 | ||

| SD | 15 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 5 | NR* | 6 |

| PD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pathology Necrosis Rate by Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A Y90 | Group B Y90 + Sorafenib | Total | |

| 100% necrosis | 6 (67%) | 3 (42%) | 9 |

| 50-99% necrosis | 1 (11%) | 2 (28%) | 3 |

| <50% necrosis | 2 (22%) | 2 (28%) | 4 |

| Total | 9 | 7 | 16 |

1 missing data due to artifact on MRI

2 missing data due to artifact on MRI

Imaging Findings

a) WHO/RECIST

Grouping all tumors, response by size criteria was observed by RECIST (p=0.08) and WHO (p=0.06), despite failing to reach significance (Figure 1). Corrected p-value of the Wilcoxon test comparing 1 month post-Y90 to baseline showed a significant reduction of WHO (p=0.047) but failed to reach significance for RECIST (p=0.077).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart.

b) EASL/mRECIST

Compared to baseline, a significant decrease in enhancing tumor diameter (p<0.01 and 0.03) and the sum of the longest and largest viable tumor diameter (p<0.01 and 0.03) was observed at 1 and 3 months, suggesting that EASL and mRECIST were equivalent (Figure 1).

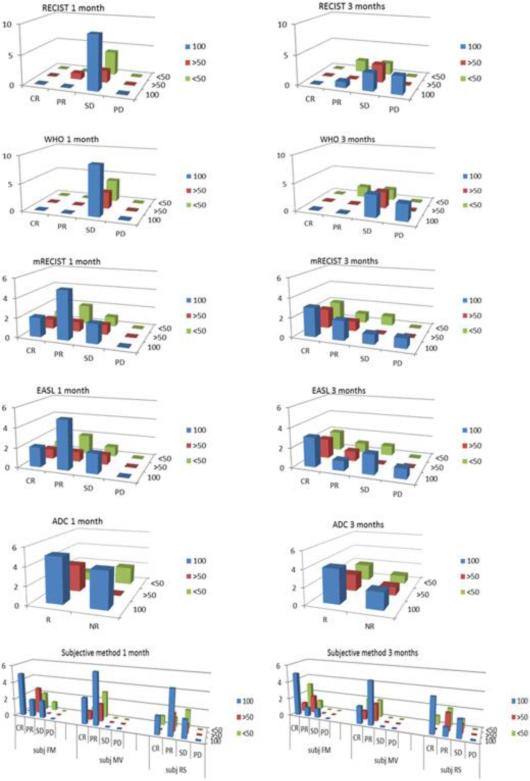

At 1 month, CRs by EASL and mRECIST were noted in 4/16 lesions; these corresponded to CPN in 2/4 of cases. At 3 months, CRs by EASL and mRECIST were noted in 7/14; this corresponded to CPN in 3/7 of cases (Table 2, Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Imaging parameter changes.

At 1 month, PRs by EASL and mRECIST were noted in 8/16 lesions; these corresponded to CPN in 5/8 of cases. At 3 months, PRs by EASL and mRECIST were noted in 3/14 and 4/14 lesions; this corresponded to CPN in 1/3 and 2/4 of cases (Table 2, Figure 2).

c) ADC

Compared to baseline, ADC (p=0.46) values did not differ at 1 or 3 months (Figure 1). With response defined as an ADC increase ≥ 5% from baseline, 9/15 and 8/12 lesions were classified as responders at 1 and 3 months, respectively (Table 2) but without being able to predict the pathological results. CPN, 50-99% and <50% necrosis were observed in 5, 3 and 1 ADC responding lesions and 4, 1 and 1 ADC non-responding lesions at 1 month (p=0.47); at 3 months, it was 4, 2 and 2 ADC responding lesions and 2, 1 and 1 ADC non-responding lesions (p=0.73) (Figure 2).

d) Subjective assessment

The subjective response assessment showed good results in predicting pathological results, particularly for one of the investigators (FM) who used DWI sequences as a complementary tool: uncertain tumor response in portions of the tumors exhibiting irregular enhancing patterns could sometimes be better classified by this investigator given diffusion restriction estimation in suspicious areas with somehow better sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive values at 1 and 3 months than other investigators (respectively 56, 86, 83 and 60; 71, 43, 56 and 60%) (Figure 2).

e) Sorafenib

Comparing group A to group B at baseline, 1 and 3 months post-treatment, no difference in terms of WHO, RECIST, EASL, mRECIST or ADC measurements was observed (Table 3). The percentage of change in WHO, RECIST, EASL, mRECIST and ADC measurements after Y90 until OLT in both groups is illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1.

Table 3.

Tumor Measurements pre and post Treatment

| group A (n=9) (median, range) | group B (n=7) (median, range) | Total (n=16) (median, range) | p-value (Mann-Whitney) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECIST (mm) | baseline | 28.7, 13.5-55.9 | 33.3, 14.9-42.5 | 29.5, 13.5-55.9 | 0.68 |

| 1 month | 26.4, 9.9-45.9 | 28.4, 13.3-36.9 | 28.4, 9.9-45.9 | 0.91 | |

| 3 months | 30.5, 5.6-45.6 | 27.7, 9.0-63.9 | 29.1, 5.6-63.9 | 0.71 | |

| WHO (mm) | baseline | 54.6, 24.4-105.8 | 57.6, 25.9-76.3 | 56.8, 24.4-105.8 | 0.68 |

| 1 month | 50.5, 19.6-90.2 | 55.0, 22.2-70.7 | 53.5, 19.6-90.2 | 1 | |

| 3 months | 61.0, 10.1-85.0 | 48.9, 16.5-119.5 | 55.0, 10.1-119.5 | 0.71 | |

| mRECIST (mm) | baseline | 28.7, 13.5-55.9 | 28.8, 14.9-36.9 | 28.8, 13.5-55.9 | 1 |

| 1 month | 9.5, 0.0-25.5 | 13.0, 0.0-34.3 | 10.0, 0.0-34.3 | 0.46 | |

| 3 months | 9.5, 0.0-26.3 | 0.0, 0.0-63.9 | 4.8, 0.0-63.9 | 0.84 | |

| EASL (mm) | baseline | 54.6, 24.4-105.8 | 56.2, 22.3-72.2 | 55.4, 22.3-105.8 | 0.76 |

| 1 month | 15.1, 0.0-50.5 | 18.6, 0.0-58.0 | 16.3, 0.0-58.0 | 0.40 | |

| 3 months | 16.9, 0.0-47.7 | 0.0, 0.0-119.5 | 7.8, 0.0-119.5 | 0.74 | |

| ADC (mm2/s × 10−3) | baseline | 1.5, 1.2-2.2 | 1.5, 1.0-1.6 | 1.5, 1.0-2.2 | 0.76 |

| 1 month | 1.5, 0.7-2.9 | 1.2, 1.1-2.2 | 1.5, 0.7-2.9 | 0.69 | |

| 3 months | 1.8, 1.1-2.7 | 1.3, 1.2-1.5 | 1.5, 1.1-2.7 | 0.06 |

f) Complete pathological response

Although not reaching significance, a trend of smaller lesions at baseline (RECIST: p=0.07, WHO: p=0.05) was observed in CPN lesions. However, 1 and 3 months after Y90, CPN could not be predicted by WHO (p=0.25 and 0.62), RECIST (p=0.35 and 0.54), EASL (p=0.49 and 0.46), mRECIST (p=0.49 and 0.60) or ADC (p=0.86 and 0.93) (Table 4). A cut-off size at baseline of 35 mm was found to be highly significant (p=0.005) in the prediction of CPN (Table 5); this cut-off was not affected by the addition of Sorafenib. Summary pathological results and radiological classification at 1 and 3 months are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 4.

CPN vs non-CPN (n=number of tumors)

| CPN (n=9) (median, range) | Non-CPN (n=7) (median, range) | Total (n=16) (median, range) | p-value (Mann-Whitney) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECIST (mm) | baseline | 28.7, 13.5-33.3 | 36.9, 19.7-55.9 | 29.5, 13.5-55.9 | 0.07 |

| 1 month | 26.4, 9.9-34.3 | 28.4, 17.3-45.9 | 28.4, 9.9-45.9 | 0.35 | |

| 3 months | 30.5, 9.0-63.9 | 27.7, 5.6-44.5 | 29.1, 5.6-63.9 | 0.54 | |

| WHO (mm) | baseline | 54.6, 24.4-57.8 | 72.2, 31.9-105.8 | 56.8, 24.4-105.8 | 0.05 |

| 1 month | 50.5, 19.6-58.0 | 56.5, 31.4-90.2 | 53.5, 19.6-90.2 | 0.25 | |

| 3 months | 61.0,16.5-119.5 | 48.9, 10.1-85.0 | 55.0, 10.1-119.5 | 0.62 | |

| mRECIST (mm) | baseline | 28.7, 13.5-33.3 | 36.5, 16.5-55.9 | 28.8, 13.5-55.9 | 0.25 |

| 1 month | 8.0, 0.0-34.3 | 13.7, 0.0-28.4 | 10.0, 0.0-34.3 | 0.49 | |

| 3 months | 9.5, 0.0-63.9 | 0.0, 0.0-26.0 | 4.8, 0.0-63.9 | 0.60 | |

| EASL (mm) | baseline | 54.6, 24.4-57.8 | 65.6, 22.3-105.8 | 55.4, 22.3-105.8 | 0.41 |

| 1 month | 14.4, 0.0-58.0 | 25.0, 0.0-55.0 | 16.3, 0.0-58.0 | 0.49 | |

| 3 months | 16.9, 0.0-119.5 | 0.0, 0.0-40.6 | 7.8, 0.0-119.5 | 0.46 | |

| ADC (mm2/s × 10−3) | baseline | 1.5, 1.2-2.2 | 1.4, 1.0-1.6 | 1.5, 1.0-2.2 | 0.35 |

| 1 month | 1.5, 0.7-2.9 | 1.4, 1.1-2.2 | 1.5, 0.7-2.9 | 0.86 | |

| 3 months | 1.5, 1.1-2.7 | 1.4, 1.2-2.0 | 1.5, 1.1-2.7 | 0.93 |

Table 5.

Pathological necrosis by size range

| ≤25mm | >25mm | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPN | 3 (60%) | 6 (54%) | 1.0 |

| Non-CPN | 2 (40%) | 5 (46%) | |

| Total | 5 | 11 |

| ≤30mm | >30mm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CPN | 6 (75%) | 3 (38%) | 0.31 |

| Non-CPN | 2 (25%) | 5 (62%) | |

| Total | 8 | 8 |

| ≤35mm | >35mm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CPN | 9 (82%) | 0 (0%) | 0.005 |

| Non-CPN | 2 (18%) | 5 (100%) | |

| Total | 11 | 5 |

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study constitutes one of the only prospective radiological-pathological studies for HCC.(4-6) This is of clinical relevance, since imaging guidelines in HCC lack these gold standard correlative studies. As a subset of the Y90 +/− Sorafenib study, we tested the hypothesis of Sorafenib treatment adjunct efficacy on Y90 as a neoadjuvant treatment or bridge to transplantation in HCC candidates for liver transplantation. No change in the lesional aspect on imaging at 1 and 3 months, nor difference in pathological results, could be observed between patients treated with Sorafenib/Y90 and those treated by Y90 alone. Hence, we concluded that on a tumor-by-tumor analysis, Sorafenib did not improve the imaging or pathological outcome in transplanted patients. However, Sorafenib, as a cytostatic and antiangiogenic agent, has a potential role in controlling the background liver disease or lesions not treated by LRT; a survival gain of nearly 3 months was noted in the SHARP trial.(14) Although Sorafenib could be considered as a treatment option after OLT, this discussion is beyond the scope of this study.(15) In relation to its antiangiogenic effect, other imaging parameters, such as perfusion- computed tomography (CT) or MRI, as well as serum biomarkers (VEGF, EGFR, PDGF, HIF-1 α) could also be more appropriate for the response assessment to Sorafenib.(16-18) Similarly, alpha feto-protein (AFP) serum level was demonstrated to be a strong predictive marker of response in AFP producer HCC patients.(19, 20) Unfortunately, as shown in Table 1, baseline AFP levels were insignificant and could not be tested.

Interestingly, a strong trend of smaller lesions at baseline was observed in the group of complete pathological response. This can be explained by the smaller tumor burden, resulting in a higher ratio of radiation/tumor volume and improved treatment efficacy. A cut-off size at baseline of 35 mm was found to be highly significant in the prediction of CPN. This tumor size is somewhat comparable to other relevant studies and recommendations with radiofrequency ablation.(21-23)

In accordance with HCC guidelines and other studies, our results support that measurement of the viable portions of tumor at 1 and 3 months is likely the best way to establish tumor response of HCC treated by targeted or locoregional therapies.(4, 24-26) However, this study suggests that older WHO and RECIST criteria are not to be considered obsolete for response assessment after Y90, a reduction in uni- and bi-dimensional measurements being observed at 1 month post-Y90. This observation can be explained by the lack of detection of intratumoral changes, such as necrosis or decrease of cellularity. EASL and mRECIST show clear methodology limitations as well: when, how and what enhancing area to measure? Anatomical changes (size, density, nodularity) after LRT are a dynamic phenomenon. These evolve within several months after Y90 and it is common that tumor borders exhibit pseudonodular area of enhancement, or that intratumoral enhancing septa are being observed. These borderline appearances may be persistent at 3 month follow-up. We experienced these difficulties when performing EASL and mRECIST assessment; it was routine for the 3 readers to use different areas of enhancing tissue to perform the measurements, with consensus adjudication being common when performing EASL/mRECIST measurements.

In comparison with TACE, the absence of lipiodol infusion in the treated area facilitated the depiction of the enhancing tissue, even though Shim et al. demonstrated in a retrospective study that lipiodol could be considered necrotic tissue on CT, and that mRECIST and EASL were found to be good predictors of pathological response.(27) However, with respect to differences in baseline size range of treated tumors (10-137 mm) and treatment technique, we advocate that it is often impossible to differentiate persistent tumor from inflammatory/regenerative process in enhancing tissue. We observed this phenomenon in our study, where enhancing tissue on one scan disappeared on subsequent imaging, likely suggesting an inflammatory and remodeling nature to the enhancement. For all aforementioned reasons, even if EASL and mRECIST criteria showed a significant change at 1 month, our clinical practice policy is to assess imaging response after 3 months of follow-up. We believe 2 imaging follow-up scans permit a better understanding of the response timeline and more confident decision-making approach for potential ulterior treatments.

Riaz et al. showed that combining measurements of the entire tumor and of its enhancing portion (especially WHO and EASL) could increase complete pathological response detection.[4] Considering imaging as potential surrogate marker of pathological response to liver-directed therapies, we advocate that combining anatomical and functional criteria are now to be considered next steps of research. Amongst these, DWI could play an important role as a potential adjunct tool in response assessment after Y90. However, when used as unique response criteria, ADC calculation was disappointing for the detection of pathological response. However, our results necessitate some comments. ADC calculation methodology was heterogeneous in the literature and highly debated. Also, DWI sequences parameters are still to be defined (use of b-values, echo-planar vs. spin-echo, single vs multishot sequences). Some authors propose calculating ADC values in the entire lesion (necrotic or viable), while others advocate studying only the borders. Even if automated segmentation software is available, some prefer a manual drawing of the ROI. Finally, a choice must be made between measurements directly performed on ADC maps or calculated after measurements on both low and high b values sequences series, that is to say bypassing automated post-processing ADC calculation (we chose this latest methodology to optimize the accuracy of series co-registration). Whatever the chosen methodology, we have to accept advantages and disadvantages. As a potential optional tool in response assessment for borderline cases, we opted for a more restrictive and discriminant technique; when possible, we placed our ROI on the suspected viable portions of the tumors. However, baseline and post-treatment ADC values in our study (Baseline: median: 1.5, range: 1.0-2.2; 1 month: 1.5, 0.7-2.9, 3 months: 1.5, 1.1-2.7) were consistent with other studies evaluating ADC changes after trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) and Sorafenib. Despite equivocal results in our study, we recognize that ADC could constitute a useful optional tool in clinical practice for borderline cases. For instance, one of the investigators (FM) showed better results in subjectively estimating CPN, partially because of DWI as ancillary data.

Further improvements in ADC methodology and software (i.e. volumetric ADC mapping) would be beneficial. The use of ADC following Sorafenib may be problematic since patients may develop hemorrhagic necrosis as a favorable treatment response, which can decrease ADC values and hence mimic residual tumor.(12, 13)

There are strengths to this study. This is the first radiological-pathological correlative study generated from a prospective randomized trial; these are rare. Second, the analysis was comprehensive and investigated relevant parameters including size (WHO, RECIST), enhancement (EASL/mRECIST) and functional imaging criteria (DWI). Third, we used the gold standard pathology analysis for quantification of necrosis. Fourth, the time from last scan to explant was <30 days, an acceptable time when imaging is reflective of pathology. There are weaknesses. Although the study is limited by sample size, finding clinical trial candidates being bridged to transplant, with solitary lesions (most in our study had solitary lesions strengthening the analysis), eligible for both Y90 and Sorafenib (randomized trial), is extremely challenging. Second, we did not identify any effect of Sorafenib on imaging or on pathology; this may have been due to the relatively small size of the tumors. Reports of Sorafenib decreasing enhancement and vascularity are usually illustrated in advanced disease (infiltrative or large tumors, +/− vascular invasion). Third, it was clear that, given irregularity of tumoral enhancement post treatment, there was a subjective element to measuring the longest enhancing tissue; these may be improved with (semi) automated volume software. Fourth, while we observed that CPN could not be predicted by WHO and RECIST response classifications, we observed that smaller lesions were nevertheless more likely to exhibit CPN at explant. This is explained by the fact that measurement of treatment response by size criteria (ignoring enhancement) almost never reaches zero; there is always a measurable defect after treatment. Finally, none of the imaging parameters evaluated in our study, including EASL/mRECIST, could reliably detect CPN at a microscopic level, highlighting the limitations of imaging methodologies that, despite being advocated by HCC guidelines, remain imperfect.

CONCLUSION

On a tumor-by-tumor analysis, the adjunct of Sorafenib to Y90 for HCC does not augment radiological or pathological response to therapy in HCC patients being bridged to transplantation. A reduction in standard size criteria (WHO, RECIST) at 1 month and a significant reduction in enhancing tumor at 1 and 3 months was observed but failed to reach significance, likely a result of cytotoxic effect of Y90. Response to treatment was equivalent when measuring by EASL or mRECIST, neither of which could reliably detect CPN. A trend of smaller lesions at baseline (35 mm cut-off) was predictive of CPN. Diffusion-weighted imaging (ADC) did not change after treatment. Standardization of ADC measurements, automated volumetric software (measurement enhancing portions of tumors) and combination response criteria (anatomic + functional), should be considered future areas of research in order to improve the detection of CPN.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 3.

Tumor-by-tumor radiological-pathological classification.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding: RS is funded in part by NIH grant CA126809.

Abbreviations

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- ADC

Apparent Diffusion Coefficient

- AFP

alpha feto-protein

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- CR

Complete Response

- CPN

Complete Pathological Necrosis

- CT

Computed Tomography

- DWI

Diffusion-Weighted Imaging

- EASL

European Association for the Study of the Liver

- ECOG PS

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

- Gd

Gadolinium

- HCC

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- LRT

Locoregional Therapy

- (m)RECIST

(modified) Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- NR

Non-Response

- OLT

Orthotopic Liver Transplant

- PD

Progressive Disease

- PR

Partial Response

- PVT

Portal Venous Thrombosis

- R

Response

- SD

Stable Disease

- ROI

Region of Interest

- SPECT

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography

- TACE

Trans-arterial chemoembolization

- TTP

Time-To-Progression

- 99Tc-MAA

Technetium-99 Macroaggregated Albumin

- T1 GRE

Gradient Echo T1-weighted

- T2 TSE

Turbo Spin-Echo T2-weighted

- UCSF

University of California in San Francisco

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- WHO

World Health Organization

- Y90

Yttrium-90 radioembolization

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: LK and RS are advisors to Nordion and Bayer/Onyx.

REFERENCES

- 1.Llovet JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bruix J, Kramer BS, Lencioni R, Zhu AX, Sherman M, et al. Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:698–711. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riaz A, Memon K, Miller FH, Nikolaidis P, Kulik LM, Lewandowski RJ, Ryu RK, et al. Role of the EASL, RECIST, and WHO response guidelines alone or in combination for hepatocellular carcinoma: Radiologic–pathologic correlation. Journal of Hepatology. 2011;54:695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riaz A, Kulik L, Lewandowski RJ, Ryu RK, Giakoumis Spear G, Mulcahy MF, Abecassis M, et al. Radiologic-pathologic correlation of hepatocellular carcinoma treated with internal radiation using yttrium-90 microspheres. Hepatology. 2009;49:1185–1193. doi: 10.1002/hep.22747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riaz A, Lewandowski RJ, Kulik L, Ryu RK, Mulcahy MF, Baker T, Gates V, et al. Radiologic-pathologic correlation of hepatocellular carcinoma treated with chemoembolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:1143–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9766-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luypaert RBS, Sourbron S, Osteaux M. Diffusion and perfusion MRI: basic physics. Eur J Radiol. 2001;38:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Gates VL, Nutting CW, Murthy R, Rose SC, Soulen MC, et al. Research reporting standards for radioembolization of hepatic malignancies. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salem R, Thurston KG. Radioembolization with 90Yttrium Microspheres: A State-of the-Art Brachytherapy Treatment for Primary and Secondary Liver Malignancies: Part 1: Technical and Methodologic Considerations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1251–1278. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000233785.75257.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, Riaz A, Ryu RK, Ibrahim S, Atassi B, et al. Radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using Yttrium-90 microspheres: a comprehensive report of long-term outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:52–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Kulik L, Wang E, Riaz A, Ryu RK, Sato KT, et al. Radioembolization Results in Longer Time-to-Progression and Reduced Toxicity Compared With Chemoembolization in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:497–507. e492. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schraml CSN, Martirosian P, Bitzer M, Lauer U, Claussen CD, Horger M. Diffusion-weighted MRI of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma during sorafenib treatment: initial results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:W301–307. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vossen JABM, Kamel IR. Assessment of tumor response on MR imaging after locoregional therapy. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;9:125–132. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinmann ANI, Koch S, Hoppe-Lotichius M, Heise M, Düber C, Schuchmann M, Otto G, Galle PR, Wörns MA. Sorafenib for recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyahara KNK, Tomoda T, Kobayashi S, Hagihara H, Kuwaki K, Toshimori J, Onishi H, Ikeda F, Miyake Y, Nakamura S, Shiraha H, Takaki A, Yamamoto K. Predicting the treatment effect of sorafenib using serum angiogenesis markers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1604–1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang TKA, Kulkarni NM, Zhu AX, Sahani DV. Monitoring response to antiangiogenic treatment and predicting outcomes in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma using image biomarkers, CT perfusion, tumor density, and tumor size (RECIST). Invest Radiol. 2012;47:11–17. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3182199bb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salem R, Miller FH, Yaghmai V, Lewandowski RJ. Response assessment methodologies in hepatocellular carcinoma: Complexities in the era of local and systemic treatments. J Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riaz A, Ryu RK, Kulik LM, Mulcahy MF, Lewandowski RJ, Minocha J, Ibrahim SM, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein response after locoregional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: oncologic marker of radiologic response, progression, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5734–5742. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Memon K, Kulik L, Lewandowski RJ, Wang E, Ryu RK, Riaz A, Nikolaidis P, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein response correlates with EASL response and survival in solitary hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial therapies: a subgroup analysis. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1112–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiina STR, Arano T, Uchino K, Enooku K, Nakagawa H, Asaoka Y, Sato T, Masuzaki R, Kondo Y, Goto T, Yoshida H, Omata M, Koike K. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: 10-year outcome and prognostic factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:569–577. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waki KAH, Katamura Y, Kawaoka T, Takaki S, Hiramatsu A, Takahashi S, Toyota N, Ito K, Chayama K. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation as first-line treatment for small hepatocellular carcinoma: results and prognostic factors on long-term follow up. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:597–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam VWNK, Chok KS, Cheung TT, Yuen J, Tung H, Tso WK, Fan ST, Poon RT. Risk factors and prognostic factors of local recurrence after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spira DFM, Lauer UM, Claussen CD, Gregor M, Bitzer M, Horger M. Comparison of different tumor response criteria in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after systemic therapy with the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib. Acad Radiol. 2011;18:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gillmore RSS, Kirkwood A, Hameeduddin A, Woodward N, Burroughs AK, Meyer T. EASL and mRECIST responses are independent prognostic factors for survival in hepatocellular cancer patients treated with transarterial embolization. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1309–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim BKKK, Park JY, Ahn SH, Chon CY, Han KH, Kim SU, Kim MJ. Prospective comparison of prognostic values of modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours with European Association for the Study of the Liver criteria in hepatocellular carcinoma following chemoembolisation. Eur J Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shim JH, Han S, Shin YM, Yu E, Park W, Kim KM, Lim YS, et al. Optimal measurement modality and method for evaluation of responses to transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma based on enhancement criteria. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.