Abstract

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is a well-established neural substrate of reward-related processes. Activity within this structure is increased by the primary and conditioned rewarding effects of abused drugs and its engagement is heavily reliant on excitatory input from structures upstream. In the case of drug seeking, it is thought that exposure to drug-associated cues engages glutamatergic VTA afferents that signal directly to dopamine cells, thereby triggering this behavior. It is unclear, however, whether glutamate input to VTA is directly involved in ethanol-associated cue seeking. Here, the role of intra-VTA ionotropic glutamate receptor (iGluR) signaling in ethanol-cue seeking was evaluated in DBA/2J mice using an ethanol conditioned place preference (CPP) procedure. Intra-VTA iGluRs α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPAR)/kainate and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDAR) were blocked during ethanol CPP expression by co-infusion of antagonist drugs 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX; AMPA/kainate) and D-(−)-2-Amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5; NMDA). Compared to aCSF, bilateral infusion of low (1 DNQX + 100 AP5 ng/side) and high (5 DNQX + 500 AP5 ng/side) doses of the AMPAR and NMDAR antagonist cocktail into VTA blocked ethanol CPP expression. This effect was site specific, as DNQX/AP5 infusion proximal to VTA did not significantly impact CPP expression. An increase in activity was found at the high but not low dose of DNQX/AP5. These findings demonstrate that activation of iGluRs within the VTA is necessary for ethanol-associated cue seeking, as measured by CPP.

1. Introduction

Dopaminergic (DA) transmission within the mesocorticolimbic system is thought to play a key role in motivated behavior. The predominant source of central DA, the midbrain [1], has been the focus of considerable research aimed at understanding the neural events that promote reward seeking. Much of this work supports the idea that reward-related signals are predominantly generated by DA cells that originate in the substantia nigra (SN) and ventral tegmental area (VTA) [2].

For example, early work has established that midbrain DA neurons are phasically activated by primary rewards [3–5]. Remarkably, reward-predicting stimuli also appear to elicit similar levels of phasic DA cell firing. In fact, after training and formation of stimulus-reward associations, the activity of midbrain DA neurons is increased almost exclusively by conditioned stimuli and not the primary rewarding stimulus [3,6]. The idea that midbrain DA activity mediates reward and cue-induced motivated behavior is also supported by behavioral studies using animal models. For example, conditioned DA release in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) core has been observed following cocaine-associated cue presentation [7]. Accordingly, antagonism of DA D1-like receptors within the NAc reduces context-induced reinstatement of ethanol seeking [8]. Similarly, blockade of amygdala D1- and D2-like receptors inhibits cue-induced ethanol-seeking behavior as suggested by its disruption of ethanol conditioned place preference (CPP) expression [9].

Additional studies identify the VTA, as a region fundamental to primary reward and cue-induced reward seeking. For instance, VTA inactivation reduced the acquisition and expression of morphine-induced CPP [10]. Activating GABAB receptors in the VTA, which putatively inhibits DA activation, also reduced morphine-induced CPP acquisition [11] and ethanol-induced CPP expression [12]. Moreover, exposure to an ethanol-associated cue activated the VTA resulting in increased c-Fos immunoreactivity [13]. These studies illustrate the VTA’s importance in the acute rewarding effects of morphine and conditioned rewarding effects of morphine and ethanol.

Although a role for VTA activity in cue-induced seeking behavior has been established, less is known about what neurochemical inputs are responsible for the excitation of VTA DA cells during drug-associated cue exposure. Considering that activity of VTA dopamine cells is regulated in part by several glutamatergic afferents [14], it is highly likely that glutamate may be involved. It has been suggested that glutamate input to the VTA may serve as a principal source of DA activation that is required for behaviorally relevant burst firing [15]. Some direct evidence does indeed indicate that glutamate input to the VTA plays a critical role in the motivational effects of abused drugs and drug-associated cues. For example, intra-VTA glutamate receptor antagonism blocked the development of place preference for environmental stimuli paired with cocaine and morphine [16,17]. Moreover, conditioned glutamate release in anticipation of cocaine delivery has been observed in VTA [18]. Taken together, this literature suggests that glutamate may serve as an important source of VTA DA innervation and is a likely signal driving cue-induced drug seeking. Despite this, few studies have assessed glutamatergic involvement in conditioned reward using ethanol as a primary reinforcer.

In the present experiment, we assessed whether glutamatergic input to the VTA was involved in the expression of ethanol-induced CPP. A well-characterized ethanol-induced CPP procedure [19] was used to establish an ethanol-cue association (acquisition) in order to evaluate the impact of iGluR antagonism on ethanol CPP expression. N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)/kainate receptors were blocked in the VTA during the ethanol-induced CPP expression test. Based on the existing literature, we hypothesized that blocking the action of this excitatory input to the VTA would reduce ethanol place preference expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animals

Male DBA/2J mice (n = 123; The Jackson Laboratory, Sacramento, CA) 6–7 weeks of age upon arrival were received in 4 separate shipments (n = 32–36/shipment). This inbred strain was chosen based on evidence from our laboratory showing that DBA/2J mice consistently develop robust ethanol-induced CPP [19]. Mice were housed in polycarbonate cages (2–4 per cage) lined with cob bedding in a colony room maintained at 21+/−1C on a 12:12 h light-dark cycle with lights on at 7:00 am. All procedures were conducted during the light phase (7:00 am – 7:00 pm). Mice were given approximately 1 week to acclimate to the colony before surgery. During this time, mice were housed in groups of four. After surgeries, mice were housed 2 per cage to reduce headmount damage and cannula loss from allogrooming. Home cage access to lab chow (5L0D PicoLab® Rodent Diet, St. Louis, MO) and water was provided ad libitum. Procedures were approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and carried out in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide For the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 2011).

2.2 Apparatus

Place conditioning was conducted using an unbiased two-compartment apparatus. Conditioning chambers (30 × 15 × 15 cm) composed of acrylic and aluminum were enclosed in ventilated boxes (Coulbourn Instruments Model E10–20) that attenuated light and sound. Within each apparatus, six infrared phototransistors were used to detect locomotor activity and time spent on each side of the chamber. Infrared light emitting diodes were mounted opposite these detectors at 5-cm intervals, 2.2 cm above the floor on the front and rear sides of each inner chamber. During each session, locomotor activity and chamber position were continuously recorded by computer. Two distinct interchangeable floors placed inside the conditioning chamber served as tactile cues. Floors were characterized by a grid (2.3-mm stainless steel rods mounted 6.4 mm apart in an acrylic frame) or hole (16-ga. stainless steel sheets perforated with 6.4 mm diameter holes on 9.5-mm staggered centers) pattern. These floor cues are equally preferred by groups of experimentally naïve DBA/2J mice [20], demonstrating the unbiased nature of the apparatus. A removable clear acrylic divider was used to separate floor cues and partition the apparatus into two compartments. To disperse olfactory cues, floors and chambers were wiped clean with a damp sponge between animals. Additional details about the apparatus and procedure can be found elsewhere [19].

2.3 Drugs

Ethanol (95%; Decon Labs, King of Prussia, PA) was prepared in a 20% v/v solution of 0.9% saline and administered intraperitoneally (IP) at a dose of 2 g/kg in a 12.5 mL/kg volume. Vehicle injections of saline were also administered IP (12.5 mL/kg).

Stock solutions of the AMPA/kainate antagonist 6,7-Dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione disodium salt (DNQX; 1 mg/mL; Tocris, Minneapolis, MN) and NMDA antagonist D-(−)-2-Amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5; 10 mg/mL; Tocris) were prepared in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; Tocris). Aliquots were stored at −80 °C and diluted to final concentrations in aCSF then combined on the day of use. Drugs were administered as a cocktail in final doses (in ng/100 nL/side) of 1 DNQX + 100 AP5 (DNQX/AP5 1 group) and 5 DNQX + 500 AP5 (DNQX/AP5 5 group). Doses were chosen based on previously published intracranial work in mice [9,21,22].

2.4 Surgical Procedure

Anesthesia was induced with 4% isoflurane (Terrell™, Piramal Critical Care Inc., Orchard Park, NY) and maintained with 1–3% in oxygen with a flow rate of 1 L/min. Mice were secured in a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) and guide cannulae (10 mm, 25 ga) were implanted 2.0 mm above the VTA (AP −3.2, ML ±0.5, DV −4.69 mm, from bregma) and held in place with permanent glass ionomer luting cement (Ketac-Cem Maxicap; 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN). Coordinates were derived from a standard mouse brain atlas [23] and selected based on literature suggesting that more medial aspects of the VTA are involved in approach behavior [24].

Cannula patency was maintained by placing stainless-steel stylets (10 mm, 32 ga) inside of each guide shaft. Mice were given 3–6 days of recovery before the start of behavioral procedures.

2.5 Histology

To verify the site of injection, tissue was collected within 24 h of the preference test and post-fixed by immersion in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde. Using a cryostat, 40-µm thick coronal sections were collected from −2.7 to −4.0 mm posterior to bregma [23] and mounted on glass slides. Once dry, tissue was stained with 0.5% cresyl violet acetate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) then coverslipped. Slides from each subject were imaged and recorded on an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with an Olympus Q-Color 3™ digital camera. Photomicrographs were analyzed and used to determine the location of each infusion.

Data from one mouse that received a unilateral injection of aCSF was excluded from statistical analyses. Data from mice that received bilateral injections of DNQX/AP5 outside of the VTA were collapsed across dose and analyzed as an additional control group, “Miss” (n = 2, n = 5 in DNQX/AP5 1 and 5 groups, respectively). A detailed list of total exclusions by group and reason for removal is included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subject Removal

| Reason for Removal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Initial n |

Final n |

Illness/ Death |

Equip. Error |

Cannula Issues |

Infusion Misses |

| aCSF | 58 | 48 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 1* |

| DNQX/AP5 1 | 31 | 25 | 1 | - | 3 | 2 |

| DNQX/AP5 5 | 30 | 23 | 1 | - | - | 5 |

Deaths prior to group assignment due to surgery & recovery issues, n = 4

This mouse received a unilateral infusion and was removed from statistical analyses

2.6 CPP Procedure

The CPP procedure was conducted over a period of 4 days and consisted of the following phases: habituation (one 5-min session), conditioning (four 5-min sessions run twice daily), and preference testing (one 30-min session). Session durations were based on temporal parameters established by our laboratory that have been reliably shown to produce a robust ethanol-induced CPP in DBA/2J mice [19].

2.6.1 Habituation

This phase of the procedure was intended to reduce the novelty of the apparatus and stress associated with initial handling and injection. Habituation sessions were run between the hours of 12 – 2 pm. Briefly, mice were removed from their home cage, weighed, and given an IP injection of saline (12.5 mL/kg) immediately prior to being placed inside the apparatus on a plain white paper floor. No floor cues were present and the acrylic divider was removed during this phase, allowing the animal to roam the apparatus freely.

2.6.2 Conditioning

Place conditioning sessions were conducted across 2 days, with two sessions (1 CS− and 1 CS+) occurring each day. During conditioning, the acrylic divider was placed in the center of the apparatus to separate grid and hole floors. Mice were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups based on DNQX/AP5 dose: aCSF (0 ng/side), DNQX/AP5 1 (1 DNQX + 100 AP5 ng/side), and DNQX/AP5 5 (5 DNQX + 500 AP5 ng/side). As mice were received in 4 separate shipments, each cohort was run as an experiment. Within each cohort, mice were assigned to one of two drug treatment groups: aCSF or DNQX/AP5. In cohorts 1–2, mice received aCSF or high dose DNQX/AP5 5, whereas in cohorts 3–4, mice received aCSF or low dose DNQX/AP5 1. Within each cohort, dose groups were subdivided into counterbalanced subgroups based on their assigned conditioning floor (Grid+ or Grid−) and left versus right floor cue orientation (GH or HG). On conditioning trials, animals in the Grid+ conditioning subgroup received ethanol paired with the grid floor and saline paired with the hole floor, whereas animals in the Grid− subgroup received ethanol paired with the hole floor and saline paired with the grid floor. All mice received saline (CS−) trials in the morning (10 am – 12 pm) and ethanol (CS+) in the afternoon (2 – 4 pm).

2.6.3 Preference Testing

Place preference was tested 24 h after the final conditioning session between the hours of 12 – 2 pm. Acrylic dividers were removed and both floor cues were presented during the test. Before the start of the test session, mice were gently restrained, stylets removed, and custom-made injectors (32 ga., 12 mm) inserted into the VTA. Polyethylene (PE20; Intramedic™) tubing connected the injectors to 10-µL gastight Hamilton syringes operated by a programmable infusion pump (Model A-74900-10: Cole Palmer, Vernon Hills, IL). Bilateral infusions of 100 nL/side were delivered over 60 s and injectors were left in place for an additional 30 s to prevent diffusion up the injection tract. After microinfusions, mice were administered saline (12.5 mL/kg, IP) in place of ethanol and immediately placed in the test chamber.

2.7 General Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Systat Software (San Jose, CA) by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the alpha level set at 0.05. Where appropriate, follow-up tests were performed to evaluate the pairwise differences among the means and p-values were Bonferroni corrected for the number of post-hoc comparisons made.

2.7.1 Locomotor Activity

Conditioning activity data were collapsed across both trials of each type (CS+ and CS−) then analyzed using two-way mixed-factor ANOVA (treatment × trial type), where “trial type” corresponds to ethanol (CS+) and saline (CS−) trials. Test activity was analyzed by one-way ANOVA (treatment).

2.7.2 Place Preference

Amount of time spent on the grid floor during the test session served as the primary dependent variable. This measure was derived from the recorded time (in sec) spent on the grid side of the apparatus divided by the test duration (30 min). This transformation yielded a dependent variable of time spent on the grid floor in units of sec/min, where 0 sec/min indicated complete aversion to and 60 sec/min indicated complete preference for the grid floor. Preference test data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (treatment × conditioning), where treatment refers to drug pretreatment groups (aCSF, Miss, 1, and 5) and conditioning represents the assigned conditioning subgroup (Grid+ and Grid−). Initial analyses were performed to determine whether there were differences in conditioning activity, test activity or mean time spent on the grid floor between similar dose groups across cohorts.

Analyses yielding significant interactions were followed up with post-hoc pairwise comparisons, with p-values Bonferroni corrected for the number of comparisons between group means.

3. Results

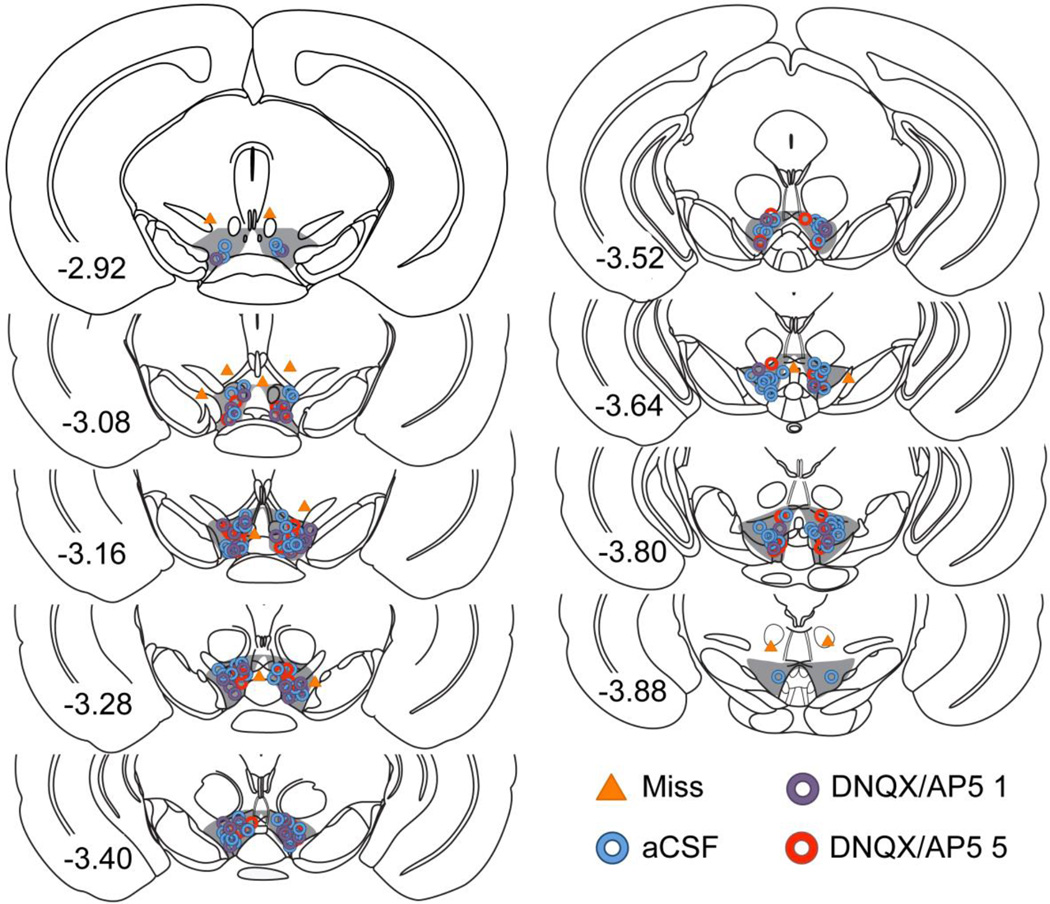

A full list of exclusions is provided in Table 1. Mice were removed from analyses due to illness or death (n = 12), missed injections (n = 8), headmount or cannula issues (n = 6), and equipment error (n = 1). Of mice excluded due to missed injections, one received a unilateral infusion of aCSF into the VTA and was permanently removed from analyses. Data from the remaining mice with missed bilateral injections (n = 2, n = 5 in DNQX/AP5 1 and 5 groups, respectively) were combined and used as an additional control group labeled “Miss". This group served to test whether the effects of DNQX/AP5 on preference expression were site-specific. In these mice, infusions were delivered < 500 µm dorsal, medial, or lateral to the VTA (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of coronal sections from the VTA showing the sites of infusion. Inclusion area for the VTA is highlighted in gray. Individual circles represent the actual placement of each infusion of aCSF (blue), 1 DNQX + 100 AP5 ng (DNQX/AP5 1, purple), and 5 DNQX + 500 AP5 ng (DNQX/AP5 1, red). The location of misplaced DNQX/AP5 infusions in mice that were included as additional controls (Miss) are presented as triangles. Numbers represent the distance of each section from bregma (in mm).

Initially, data were analyzed using three-way ANOVA (cohort × treatment × conditioning) to determine whether there were significant differences in grid times for each dose group (aCSF, 1, and 5) between cohorts. No significant effect of cohort was found for aCSF (compared across cohorts 1–4), DNQX/AP5 1 (compared across cohorts 3–4), or DNQX/AP5 5 (compared across cohorts 1–2) groups.

After confirming there was no main effect of cohort and no two- or three-way interactions with cohort (F’s < 1), data from all cohorts were combined. Data were then analyzed by two-way ANOVA (treatment × conditioning) across all treatment groups (aCSF, 1, 5 and Miss).

3.1 Conditioning Activity

Conditioning trial activity was higher on ethanol (CS+) trials than on saline (CS−) trials (Table 2), as is typically seen in DBA/2J mice [25]. Two-way ANOVA showed significant main effects of trial type [F(1,99) = 338.9, p < 0.001] and treatment [F(3,99) = 3.9, p = 0.012], but no interaction. Post-hoc analyses revealed that locomotor activity during conditioning was significantly higher in the DNQX/AP5 1 group compared to the aCSF group (Bonferroni-corrected p = 0.017). Since the intra-VTA infusions were not administered on conditioning days and all groups were treated identically during this phase, we can only attribute the higher level of activity in the DNQX/AP5 1 group to sampling error.

Table 2.

Locomotor Activity

Mean Activity Counts per Minute (±SEM) during conditioning and preference test.

| Group | n | CS+ trials | CS− trials | Preference Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aCSF | 48 | 97.2 ± 4.8 | 46.3 ± 1.9 | 28.2 ± 1.5 |

| DNQX/AP5 1a | 25 | 117.5 ± 5.6 | 50.4 ± 2.1 | 23.3 ± 1.8b |

| DNQX/AP5 5 | 23 | 96.7 ± 5.2 | 45.2 ± 5.3 | 43.7 ± 8.7 |

| Miss | 7 | 84.4 ± 15.0 | 49.0 ± 1.8 | 49.4 ± 12.1 |

Conditioning activity differs from aCSF, p < 0.02

Differs from DNQX/AP5 5, p < 0.05

3.2 Test Activity

Test activity means (±SEM) for each group are included in Table 2. Locomotor activity during the preference test was significantly higher in mice administered the higher dose combination of DNQX/AP5 compared to those administered the lower dose combination. Analyses yielded a significant main effect of treatment [F(3,99) = 5.0, p = 0.003] and post hoc comparisons showed that test activity significantly differed only between the DNQX/AP5 5 and 1 dose groups (Bonferroni-corrected p = 0.015).

3.3 Place Preference

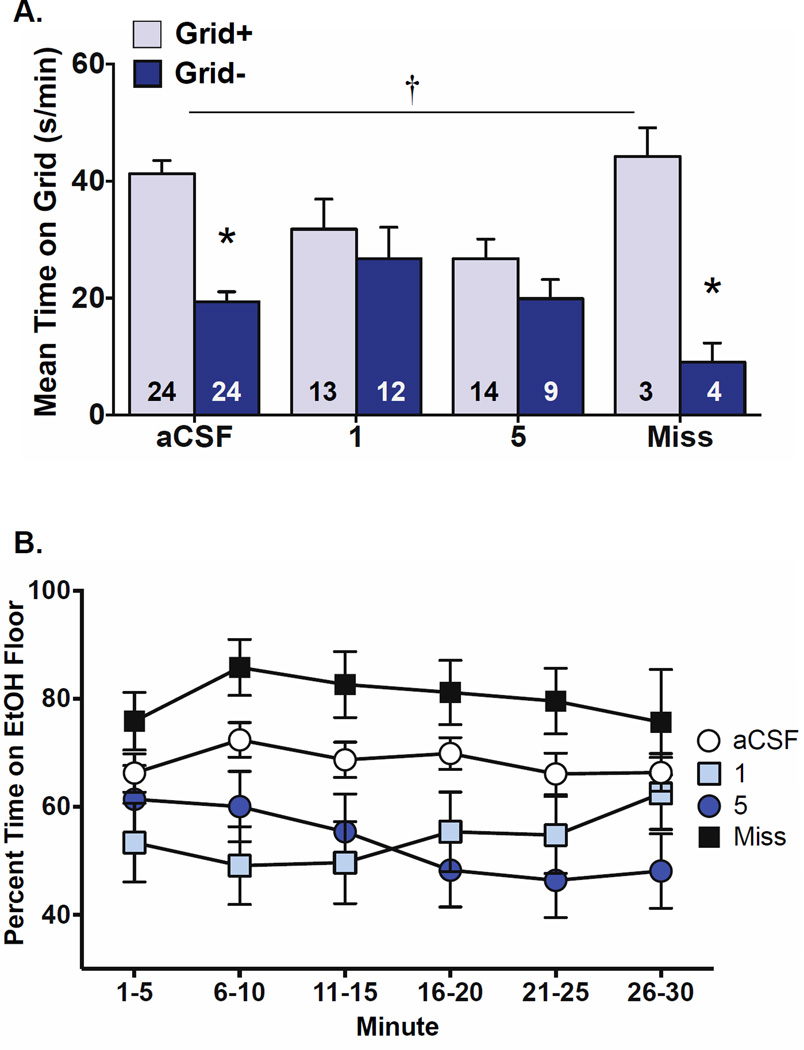

As shown in Figure 2A, expression of ethanol-induced CPP was blocked by intra-VTA infusion of DNQX/AP5. This effect was supported by a significant treatment × conditioning interaction [F(3,95) = 4.7, p = 0.004], a main effect of conditioning [F(1,95) = 29.2, p < 0.001], and no main effect of treatment.

Figure 2.

Antagonism of NMDA and AMPA receptors in the VTA blocks ethanol-induced CPP expression. (A) Data are expressed as mean time spent on the grid floor (s/min + SEM) by Grid+ and Grid− conditioning subgroup animals in treatment groups aCSF, 1 (1 DNQX + 100 AP5 ng/side), 5 (5 DNQX + 500 AP5 ng/side), and Miss. Ethanol-induced CPP expression was blocked by infusion of both doses of DNQX/AP5 into the VTA. Conversely, ethanol-induced CPP was not affected by aCSF infusion into the VTA or DNQX/AP5 infusion outside the VTA. This was supported by a treatment (aCSF, 1, 5, Miss) by conditioning (Grid+ vs. Grid−) interaction and a significant difference between Grid+ and Grid− in the aCSF and Miss groups only; bar values represent the number of animals in each subgroup; † p = 0.004 treatment × conditioning; *p ≤ 0.001 between Grid+ and Grid−. (B) Preference expression in 5-min intervals across the CPP test. Data are expressed as Mean (±SEM) percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor. Across the test, mice that received intra-VTA infusion of DNQX/AP5 (groups 1 and 5) spent significantly less time on the ethanol-paired floor compared to mice in aCSF and Miss groups (p = 0.002 main effect of treatment).

Post-hoc comparisons of grid times between conditioning subgroups within each treatment group showed that only control mice administered aCSF or DNQX/AP5 outside of the VTA expressed CPP. This was confirmed by significant differences in grid time between Grid+ and Grid− conditioning subgroups (Bonferroni-corrected p’s ≤ 0.001) in groups aCSF and Miss only. Since Levene’s test suggested non-homogeneity of variance in the overall ANOVA [F(7,95) = 4.5, p < 0.001], we also did post-hoc comparisons using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test. These tests showed a significant difference between conditioning subgroups only within the aCSF control group (U = 36, Bonferroni-corrected p < 0.00001). The difference between conditioning subgroups within the Miss group met the conventional criterion for significance (U = 0, p < 0.04), but missed the Bonferroni criterion.

To simplify analysis of test performance over time within the test session, test data were converted to percent time spent on the ethanol-paired floor during consecutive 5-min bins and averaged across conditioning subgroups. These time-course analyses showed that preference for the ethanol-paired floor was immediately and consistently reduced in mice that received intra-VTA DNQX/AP5 compared to controls (Fig. 2B), yielding a significant main effect of treatment [F(3,99) = 5.4, p = 0.002] but no significant effect of time interval or interaction.

4. Discussion

In the present experiment, intra-VTA blockade of AMPA and NMDA receptors by antagonist drugs DNQX and AP5 prevented the expression of a place preference induced by ethanol. Ethanol-induced CPP expression was blocked in both dose groups, indicating that the lower doses produced an asymptotic effect at both receptor types. In contrast, neither administration of aCSF in the VTA nor DNQX/AP5 outside the VTA significantly affected ethanol-induced CPP expression. The absence of effect in these controls suggests that reduced expression of ethanol-induced CPP in DNQX/AP5 groups was not due to a nonspecific effect of VTA manipulation (aCSF) or drug action at sites proximal to VTA (Miss), where drug may have spread. Moreover, the impact of DNQX/AP5 on preference expression cannot be solely attributed to its effects on activity. Only the higher dose combination of DNQX/AP5 (5 DNQX + 500 AP5) produced a significant increase in locomotor activity compared to the lower dose combination (1 DNQX + 100 AP5), which prevented expression without significantly impacting activity. Overall, results demonstrate the importance of VTA glutamate input in ethanol-induced CPP expression.

This experiment was designed to evaluate the involvement of VTA glutamate input in the expression of a place preference conditioned using ethanol. The hypothesis that glutamate input to VTA is involved in this behavior was based on several key findings in the existing literature. First, systemic activity of glutamate systems has been shown to be important for ethanol-seeking behavior. For instance, it has been reported that NMDA/glycine and AMPA receptor antagonism blocks cue-induced reinstatement of ethanol seeking [26]. Previous studies have demonstrated a role for metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) in ethanol seeking. In one study, stress- and cue-induced ethanol seeking were reduced by activation of group II mGluRs [27], while in another, mGluR subtype 5 antagonism reduced cue-induced reinstatement of ethanol seeking [28]. Cue-induced reinstatement of ethanol seeking was increased by positive allosteric modulation of AMPA receptors [29] and decreased by genetic deletion of the GluR-C AMPA subunit [30], further supporting a role for iGluRs. In addition, recent work has indicated that glutamate inputs to VTA DA neurons influence ethanol relapse through combined action at NMDA and AMPA receptors [31].

Next, the involvement of mesocorticolimbic DA in the conditioned motivational effects of reward-associated stimuli has been well established. Numerous studies have demonstrated increased release and/or activity of DA in terminal fields following exposure to cues associated with previous reward experience [32–35]. This increased terminal field release appears to promote reward seeking [36] and is likely derived from the VTA, a principal source of DA in this pathway [37–39].

Beyond this, additional evidence implicates the VTA in reward-seeking behavior. Studies have shown that activation of appetitive behaviors, such as approach is associated with DA activity in the VTA, specifically (reviewed in [2,24]). Not only is the VTA engaged during seeking, but evidence suggests this region must be “online” and active to produce reward-related behavior. For example, transient inactivation of the VTA with lidocaine blocked expression of morphine CPP [10], whereas bupivacaine blocked pup- but not cocaine-induced CPP expression [40]. Combined intra-VTA administration of the GABAA and GABAB receptor agonists muscimol and baclofen has been demonstrated to block drug-primed reinstatement of cocaine seeking [41] and cue-induced increases in responding for food (i.e., Pavlovian-instrumental transfer) [42]. Notably, our lab has shown that baclofen administered into the VTA blocked the expression of an ethanol-induced CPP [12], thus highlighting the necessity of the VTA and its activation in driving ethanol-induced CPP expression within our procedure.

Finally, there is some evidence to suggest that glutamatergic afferents of the VTA are essential for reward-seeking behavior. Glutamate input to VTA has been shown to be essential for the induction of phasic DA cell firing (for reviews see [15,43–45]). There is also evidence of drug-cue induced conditioned glutamate release in VTA [18], which indicates the functional relevance of this excitatory input. Moreover, blocking VTA glutamate receptors has been shown to reduce cue-induced reinstatement of morphine seeking [46] and cocaine-primed reinstatement of drug-seeking [47]. Together, the literature indicates that glutamatergic innervation of the VTA may serve an essential role in triggering drug seeking induced by conditioned cue exposure. Our results support this idea and demonstrate that AMPA and/or NMDA receptor activation within the VTA are necessary for the expression of ethanol-induced place preference. Previously, our lab has shown that the VTA is activated by an ethanol-associated cue [13] and inhibition of the VTA by baclofen blocks ethanol-induced CPP expression [12]. Here, we show that iGluR activation within the VTA is also necessary for the expression of ethanol-induced place preference. This work extends our earlier findings and demonstrates that not only is ethanol-induced place preference expressed through the VTA, it is done so through a glutamatergic signaling mechanism.

During the test, locomotor activity in the higher dose combination (5+500 ng/side) DNQX/AP5 group was significantly increased compared to the lower dose combination (1+100 ng/side) group. Although a trend toward increased activity was found in high dose DNQX/AP5-treated mice compared to the aCSF-treated controls, neither a low dose of DNQX/AP5 nor infusion of DNQX/AP5 outside of the VTA (Miss) significantly affected activity compared to aCSF. The overall pattern of results suggests that glutamate signaling within the VTA normally regulates locomotor activity. In general, these findings are in agreement with previous studies, as increased activity following intra-VTA antagonism of NMDA receptors with AP5 has been reported [17,48–50]. Moreover, these studies point to NMDA receptor antagonism by AP5 as the driving force behind the observed increase in basal locomotor activity.

Previously, a significant negative correlation between test activity and preference expression has been reported [51]. Therefore, results from the CPP test must be carefully interpreted when an activity effect is noted, as increased test activity can compete and interfere with preference expression. Although it is possible that increased activity in the higher dose DNQX/AP5 group disrupted ethanol-induced place preference expression, results from the lower dose DNQX/AP5 group would argue against this explanation alone, as preference was disrupted while activity was unaffected. Moreover, test activity levels were similarly elevated in the group (Miss) that received DNQX/AP5 outside of the VTA. Notably, this control group showed significant place preference suggesting that DNQX/AP5-induced activity increases alone did not impact place preference expression. Thus, it is unlikely that reduced preference in the DNQX/AP5 5 group was simply an artifact of increased activity.

The present experiment was designed to broadly assess the involvement of glutamate input to VTA in ethanol-induced CPP expression. Thus, we chose to combine antagonist drugs targeting both AMPA and NMDA receptors to comprehensively block glutamate innervation of VTA. These receptors were targeted based on evidence that VTA DA cells express both AMPA and NMDA iGluRs [52]. However, it is possible that one of these receptors may play a more important role in preference expression. Indeed, previous work has showed that AMPAR but not NMDAR antagonism alone blocks cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats [53]. Since AMPA and NMDA receptor antagonists were co-administered in this study, it is not clear from these data what individual contributions AMPA and NMDA receptors may provide. Therefore, future studies are needed to determine whether there are distinct roles for AMPA and/or NMDA receptors in ethanol-induced CPP expression.

5. Conclusions

Altogether, the present findings demonstrate that expression of ethanol-induced place preference requires the activation of iGluRs within the VTA. This further identifies the VTA as an important neural substrate underlying expression of the conditioned rewarding effects of ethanol and indicates that excitatory input to VTA may drive ethanol-cue seeking behavior.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this paper was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AA007702 and T32AA007468. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. A Scholar Award from the ARCS Foundation Portland Chapter and a Graduate Scholarship from the OHSU-Vertex Partnership provided additional support (MMP). Experiments reported here comply with the current laws of the United States.

References

- 1.German DC, Manaye KF. Midbrain dopaminergic neurons (nuclei A8, A9, and A10): Three-dimensional reconstruction in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993;331:297–309. doi: 10.1002/cne.903310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:483–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ljungberg T, Apicella P, Schultz W. Responses of monkey dopamine neurons during learning of behavioral reactions. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;67:145–163. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz W. Responses of midbrain dopamine neurons to behavioral trigger stimuli in the monkey. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1986;56:1439–1461. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.5.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz W, Apicella P, Ljungberg T. Responses of monkey dopamine neurons to reward and conditioned stimuli during successive steps of learning a delayed response task. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:900–913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-00900.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schultz W. A Neural Substrate of Prediction and Reward. Science. 1997;275:1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito R, Dalley JW, Howes SR, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Dissociation in conditioned dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens core and shell in response to cocaine cues and during cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7489–7495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07489.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhri N, Sahuque LL, Janak PH. Ethanol seeking triggered by environmental context is attenuated by blocking dopamine D1 receptors in the nucleus accumbens core and shell in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2009;207:303–314. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1657-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gremel CM, Cunningham CL. Involvement of amygdala dopamine and nucleus accumbens NMDA receptors in ethanol-seeking behavior in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1443–1453. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moaddab M, Haghparast A, Hassanpour-Ezatti M. Effects of reversible inactivation of the ventral tegmental area on the acquisition and expression of morphine-induced conditioned place preference in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;198:466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuji M, Nakagawa Y, Ishibashi Y, Yoshii T, Takashima T, Shimada M, et al. Activation of ventral tegmental GABAB receptors inhibits morphine-induced place preference in rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;313:169–173. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00642-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bechtholt AJ, Cunningham CL. Ethanol-induced conditioned place preference is expressed through a ventral tegmental area dependent mechanism. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119:213–223. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill KG, Ryabinin AE, Cunningham CL. FOS expression induced by an ethanol-paired conditioned stimulus. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2007;87:208–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sesack SR, Carr DB, Omelchenko N, Pinto A. Anatomical substrates for glutamate-dopamine interactions: evidence for specificity of connections and extrasynaptic actions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;1003:36–52. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White FJ. Synaptic regulation of mesocorticolimbic dopamine neurons. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1996;19:405–436. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.002201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris GC, Aston-Jones GS. Enhanced morphine preference following prolonged abstinence: association with increased Fos expression in the extended amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:292–299. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris GC, Wimmer M, Byrne R, Aston-Jones GS. Glutamate-associated plasticity in the ventral tegmental area is necessary for conditioning environmental stimuli with morphine. Neuroscience. 2004;129:841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You Z-B, Wang B, Zitzman D, Azari S, Wise RA. A role for conditioned ventral tegmental glutamate release in cocaine seeking. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:10546–10555. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2967-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham CL, Ferree NK, Howard MA. Apparatus bias and place conditioning with ethanol in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2003;170:409–422. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1559-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gremel CM, Cunningham CL. Effects of disconnection of amygdala dopamine and nucleus accumbens N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors on ethanol-seeking behavior in mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;31:148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jennings JH, Sparta DR, Stamatakis AM, Ung RL, Pleil KE, Kash TL, et al. Distinct extended amygdala circuits for divergent motivational states. Nature. 2013;496:224–228. doi: 10.1038/nature12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; 2001. pp. 1–350. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikemoto S. Dopamine reward circuitry: two projection systems from the ventral midbrain to the nucleus accumbens-olfactory tubercle complex. Brain Research Reviews. 2007;56:27–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunningham CL, Niehus DR, Malott DH, Prather LK. Genetic differences in the rewarding and activating effects of morphine and ethanol. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1992;107:385–393. doi: 10.1007/BF02245166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bäckström P, Hyytiä P. Ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists modulate cue-induced reinstatement of ethanol-seeking behavior. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:558–565. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000122101.13164.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Y, Dayas CV, Aujla H, Baptista MAS, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Activation of Group II Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors Attenuates Both Stress and Cue-Induced Ethanol-Seeking and Modulates c-fos Expression in the Hippocampus and Amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:9967–9974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2384-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroeder JP, Spanos M, Stevenson JR, Besheer J, Salling M, Hodge CW. Cue-induced reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior is associated with increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation in specific limbic brain regions: blockade by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cannady R, Fisher KR, Durant B, Besheer J, Hodge CW. Enhanced AMPA receptor activity increases operant alcohol self-administration and cue-induced reinstatement. Addict Biol. 2012;18:54–65. doi: 10.1111/adb.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchis-Segura C, Borchardt T, Vengeliene V, Zghoul T, Bachteler D, Gass P, et al. Involvement of the AMPA receptor GluR-C subunit in alcohol-seeking behavior and relapse. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:1231–1238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4237-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisenhardt M, Leixner S, Luján R, Spanagel R, Bilbao A. Glutamate Receptors within the Mesolimbic Dopamine System Mediate Alcohol Relapse Behavior. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:15523–15538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2970-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bassareo V, De Luca MA, Di Chiara G. Differential impact of pavlovian drug conditioned stimuli on in vivo dopamine transmission in the rat accumbens shell and core and in the prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2007;191:689–703. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duvauchelle CL, Ikegami A, Castaneda E. Conditioned increases in behavioral activity and accumbens dopamine levels produced by intravenous cocaine. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:1156–1166. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.6.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duvauchelle CL, Ikegami A, Asami S, Robens J, Kressin K, Castaneda E. Effects of cocaine context on NAcc dopamine and behavioral activity after repeated intravenous cocaine administration. Brain Research. 2000;862:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blackburn JR, Phillips AG, Jakubovic A, Fibiger HC. Dopamine and preparatory behavior: II. A neurochemical analysis. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1989;103:15–23. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips PEM, Stuber GD, Heien MLAV, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Subsecond dopamine release promotes cocaine seeking. Nature. 2003;422:614–618. doi: 10.1038/nature01476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cachope R, Cheer JF. Local control of striatal dopamine release. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;8:188. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yun IA, Wakabayashi KT, Fields HL, Nicola SM. The ventral tegmental area is required for the behavioral and nucleus accumbens neuronal firing responses to incentive cues. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:2923–2933. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5282-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Doyon WM, Clark JJ, Phillips PEM, Dani JA. Controls of tonic and phasic dopamine transmission in the dorsal and ventral striatum. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;76:396–404. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.056317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seip KM, Morrell JI. Transient inactivation of the ventral tegmental area selectively disrupts the expression of conditioned place preference for pup- but not cocaine-paired contexts. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;123:1325–1338. doi: 10.1037/a0017666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McFarland NR, Lee J-S, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. Comparison of transduction efficiency of recombinant AAV serotypes 1, 2, 5, and 8 in the rat nigrostriatal system. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009;109:838–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murschall A, Hauber W. Inactivation of the ventral tegmental area abolished the general excitatory influence of Pavlovian cues on instrumental performance. Learning & Memory. 2006;13:123–126. doi: 10.1101/lm.127106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geisler S, Wise RA. Functional implications of glutamatergic projections to the ventral tegmental area. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 2008;19:227–244. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2008.19.4-5.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalivas PW. Neurotransmitter regulation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Research Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18:75–113. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90008-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Overton PG, Clark D. Burst firing in midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Brain Research Brain Research Reviews. 1997;25:312–334. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00039-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9495561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bossert JM, Liu SY, Lu L, Shaham Y. A role of ventral tegmental area glutamate in contextual cue-induced relapse to heroin seeking. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:10726–10730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3207-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun W, Akins CK, Mattingly AE, Rebec GV. Ionotropic glutamate receptors in the ventral tegmental area regulate cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:2073–2081. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornish JL, Nakamura M, Kalivas PW. Dopamine-Independent Locomotion Following Blockade of N-Methyl-D-aspartate Receptors in the Ventral Tegmental Area. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;298:226–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harris GC, Aston-Jones GS. Critical role for ventral tegmental glutamate in preference for a cocaine-conditioned environment. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:73–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kretschmer BD. Modulation of the mesolimbic dopamine system by glutamate: role of NMDA receptors. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;73:839–848. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gremel CM, Cunningham CL. Role of test activity in ethanol-induced disruption of place preference expression in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2007;191:195–202. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0651-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Albin RL, Makowiec RL, Hollingsworth ZR, Dure LS, Penney JB, Young AB. Excitatory amino acid binding sites in the basal ganglia of the rat: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Neuroscience. 1992;46:35–48. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90006-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahler SV, Smith RJ, Aston-Jones GS. Interactions between VTA orexin and glutamate in cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2013;226:687–698. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2681-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]