Abstract

We previously reported on a method for the facile removal of 4-methoxybenzyl (Mob) and acetamidomethyl (Acm) protecting groups from cysteine (Cys) and selenocysteine (Sec) using 2,2′-dithiobis-5-nitropyridine (DTNP) dissolved in trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (DTNP/TFA), with or without thioanisole. The use of this reaction mixture removes the protecting group and replaces it with a 2-thio(5-nitropyridyl) (5-Npys) group. This results in either a mixed selenosulfide bond or disulfide bond (depending on the use of Sec or Cys), which can subsequently be reduced by thiolysis. A major disadvantage of thiolysis is that excess thiol must be used to drive the reaction to completion and then removed before using the Cys- or Sec-containing peptide in further applications. Here, we report a further advancement of this method as we have found that ascorbate at pH 4.5 and 25 °C will reduce the selenosulfide to the selenol. Ascorbolysis of the mixed disulfide between cysteine and 5-Npys is much less efficient, but can be accomplished at higher concentrations of ascorbate at pH 7 and 37 °C with extended reaction times. We envision that our improved method will allow for in situ reactions with alkylating agents and electrophiles without the need for further purification, as well as a number of other applications.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

The 2-thio(5-nitropyridyl) (5-Npys) group can be used to temporarily mask the reactivity of the thiol and selenol groups of cysteine and selenocysteine. Here we report on a method to remove the 5-Npys group using ascorbate instead of thiols. The use of ascorbate to selectively deprotect the 5-Npys group has multiple, possible applications including: interchain selenosulfide and diselenide formation, use in native chemical ligation reactions, and in situ alkylation reactions.

INTRODUCTION

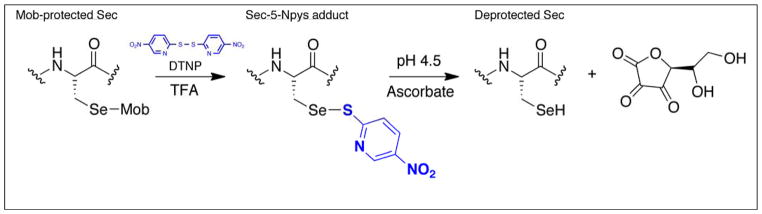

We previously reported on a method for the facile removal of 4-methoxybenzyl (Mob) and acetamidomethyl (Acm) protecting groups from cysteine (Cys) and selenocysteine (Sec) using 2,2′-dithiobis-5-nitropyridine (DTNP) dissolved in TFA (DTNP/TFA), with or without thioanisole as shown in Figure 1 [1–2]. Prior to the development of this method, removal of these protecting groups required harsh conditions [3, 4]. DTNP can be added to all standard cleavage cocktails that are used to cleave the peptide from the solid support in Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) with simultaneous removal of the protecting group from Cys or Sec.

Figure 1.

Deprotection of Sec(Mob) using TFA/DTNP followed by thiolysis. Deprotection of Cys(Mob) works similarly, but requires the use of thioanisole as an additive.

However, one limitation of this method is that it requires the use of excess thiol in a subsequent step to remove the 5-Npys group from Sec or Cys. In both cases, but especially for Sec, a very large excess of thiol must be added in order to ensure that thiolysis results in production of a free Cys-thiol or free Sec-selenol. In many cases a mixture of free thiol/selenol and mixed disulfide/selenosulfide peptide results [2]. Another drawback of thiolysis is that purification must be performed if the peptide is to be used in a subsequent application.

Here, we present a modification to our earlier method that replaces thiolysis of the mixed disulfide/selenosulfide bond in Figure 1 with ascorbolysis as shown in Figure 2. It is known that ascorbate will reduce reactive disulfide bonds such as DTNP and 5,5'-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid (better known as DTNB), with a lesser ability to reduce cystine and disulfide bonds with similar reactivity [5, 6]. Ascorbate has also been used for the specific reduction of S-nitrosothiols in the biotin switch assay [7, 8].

Figure 2.

Deprotection of Sec(Mob) using TFA/DTNP followed by ascorbolysis.

We envision that our improved method will allow for in situ reactions with alkylating agents and electrophiles without the need for further purification, as well as a number of other applications. Another advantage of using ascorbate to reduce the selenosulfide in Figure 2 is that excess ascorbate in solution helps quench dissolved oxygen in the sample, thereby keeping the selenol in a reduced form.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We first set out to test the ability of ascorbate to reduce Sec(5-Npys) and Cys(5-Npys) by visual inspection since ascorbolysis of the peptides should liberate 5-Npys, which has an absorbance maximum at 412 nm, similar to thio-nitrobenzoic acid, and a yellow color produced is visible to the naked eye at sufficiently high concentration. We found that the reaction between ascorbate and Sec(5-Npys) is fast upon addition of ascorbate to Sec(5-Npys) at a pH of 4.5 as a color change from clear to bright yellow was observed almost immediately (within minutes of addition). In contrast, we observed that the reaction between ascorbate and Cys(5-Npys) is slow, as a color change could only be observed after hours of reaction and most prominently when heated to 37 °C.

Initially, we tried to add ascorbic acid directly to the solution of peptide dissolved in the cleavage cocktail containing DTNP and TFA (plus scavengers), after allowing for sufficient reaction time for Sec(Mob) to be converted to Sec(5-Npys). Such a procedure would be advantageous because such “one-pot” procedures are highly desirable in peptide chemistry [9–11]. However, the results of this reaction showed that ascorbate could not deprotect the Sec(5-Npys) in TFA (pH ~2) and thus, ascorbolysis was performed in aqueous solution.

Next, we explored various reaction conditions for both Sec(5-Npys) and Cys(5-Npys) in order to maximize the extent of deprotection. We chose a pH of 4.5 as a lower bound because it is just slightly above the pKa of ascorbic acid, 4.2 [12]. At this pH ascorbic acid will be 67% ionized and in the active enolate form. Our chosen reaction pH of 4.5 fits well with the findings of Dutton and coworkers who showed that the use of DTNP to catalyze heterodisulfide formation was fastest at pH values between 3.5 and 6.5 [13]. Pyridyl disulfides are more reactive at acidic pH [14] due to protonation of the pyridine nitrogen atom, which in the case of both Sec(5-Npys) and Cys(5-Npys) greatly polarizes the mixed disulfide bond. This polarization of the mixed disulfide bond activates the disulfide bond towards thiol/disulfide exchange as well as reduction by ascorbate [14]. Thus our chosen reaction pH of 4.5 is a balance between conversion of ascorbic acid to the reactive ascorbate (enolate) form, and the maximum effective range of DTNP reactivity.

In order to determine whether ascorbate could convert Sec(5-Npys) to Sec-SeH, we incubated a Sec-containing test peptide (crude product without HPLC purification) with 5-fold excess ascorbate at either pH 4.5 or pH 7.0 under various reaction conditions as summarized in Table 1. Ascorbolysis was monitored by HPLC and ESI-MS. We found that near complete deprotection occurred at pH 4.5 and 25 ºC after 4 hrs of reaction time (reaction Se1, Table 1). Our results show that pH 4.5 was slightly better than pH 7.0 for achieving deprotection, but deprotection was very similar under all of the conditions listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of deprotection conditions for Cys- and Sec-peptides.

| Reaction number | pH | Temperature (°C) | Time (hrs) | Asc:Peptide | % Deprotected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Se1 | 4.5 | 25 | 4 | 5:1 | > 95 |

| Se2 | 4.5 | 25 | 24 | 5:1 | > 95 |

| Se3 | 4.5 | 37 | 4 | 5:1 | > 95 |

| Se4 | 4.5 | 37 | 24 | 5:1 | > 95 |

| Se5 | 7 | 25 | 4 | 5:1 | 90–95 |

| Se6 | 7 | 25 | 24 | 5:1 | 90–95 |

| Se7 | 7 | 37 | 4 | 5:1 | 90–95 |

| Se8 | 7 | 37 | 24 | 5:1 | 90–95 |

| S1 | 4.5 | 25 | 4 | 100:1 | 50–55 |

| S2 | 4.5 | 25 | 24 | 100:1 | 50–55 |

| S3 | 4.5 | 37 | 4 | 100:1 | 50–55 |

| S4 | 4.5 | 37 | 24 | 100:1 | 55–60 |

| S5 | 7 | 25 | 4 | 100:1 | 35–40 |

| S6 | 7 | 25 | 24 | 100:1 | 45–50 |

| S7 | 7 | 37 | 4 | 100:1 | 50–55 |

| S8 | 7 | 37 | 24 | 100:1 | 70–75 |

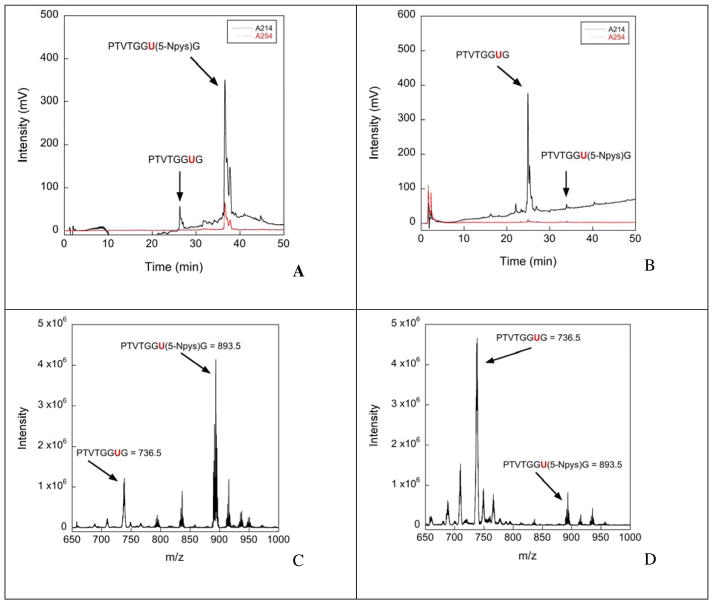

The percentage of deprotection was estimated by measuring the area under the peak in the HPLC chromatogram compared to the control. In Figure 3A we show the HPLC chromatogram of the Sec-peptide without addition of ascorbate (control), while the effect of addition of 5-fold excess ascorbate to the Sec-peptide is shown in Figure 3B. The identity of each peak was determined by ESI-MS analysis before and after treatment with ascorbate. The MS data is shown in Figure 3C and Figure 3D. We note that some of the 5-Npys group was removed during work up of the peptide by an undetermined mechanism before the addition of ascorbate. These results show that ascorbate successfully removes the 5-Npys group from Sec under relatively mild conditions.

Figure 3.

HPLC chromatograms and mass spectrometry of the Sec-containing test peptide treated with ascorbate under various conditions for 24 hrs with a 5:1 ascorbate: peptide ratio. (A) HPLC chromatogram of the Sec-containing peptide without ascorbate treatment (control). (B) HPLC chromatogram of the Sec-containing peptide treated with ascorbate at 25 °C and pH = 4.5. (C) Mass spectrum of the Sec-containing peptide without ascorbate treatment (control). (D) Mass spectrum of the Sec-containing peptide treated with ascorbate at 25 °C and pH = 4.5.

Our initial experiments with the Cys-containing peptide using a ratio of ascorbate to peptide that ranged from 2:1 to 20:1 for 4 hrs at pH 4.5 and 25 °C (conditions analogous to those used for complete conversion of Sec(5-Npys) to Sec-SeH) did not result in conversion of Cys(5-Npys) to Cys-SH as determined by HPLC analysis (data not shown). In order to see if we could deprotect Cys(5-Npys) with ascorbate, we increased the ratio of ascorbate to Cys-peptide to 100:1. At this ratio of ascorbate to peptide we found that ~50% deprotection was achieved at pH 4.5 and 25 °C with a reaction time of 24 hrs (reaction S2, Table 1). We next tried to push the reaction to completion by raising the pH from 4.5 to 7 (potassium phosphate buffer, reaction S6, Table 1), but the result was nearly an identical level of deprotection as determined by HPLC analysis. We then explored the effect of elevated temperature on the reaction and found that increasing the temperature from 25 ° to 37 °C at pH 7 with a reaction time of 24 hrs improved deprotection (reaction S8, Table 1). One difference at pH 7 compared to pH 4.5 was the appearance of the disulfide form of the peptide in the HPLC chromatogram (Figure 4A). Using these reaction conditions conversion of Cys(5-Npys) to Cys-SH increased to 70–75%, but the reaction is still slow as is evidenced by the extended reaction time, high concentration of ascorbate, and incomplete removal of the 5-Npys group. Both HPLC and mass analysis show incomplete removal of the 5-Npys group from Cys under these conditions (Figures 4A and 4B).

Figure 4.

HPLC and mass spectroscopic analysis of the Cys-containing test peptide treated with 100-fold excess ascorbate. (A) HPLC chromatogram of the Cys(5-Npys)-containing peptide treated with ascorbate at 37 °C, pH = 7 for 24 hrs. (B) Mass spectrum of the Cys-containing peptide treated with ascorbate at 37 °C and pH = 7.0 for 24 hrs.

Our results do indeed show that ascorbate was very efficient in converting Sec(5-Npys) to Sec-SeH at acidic pH (Table 1). Increasing the reaction pH to 7 slightly decreases the extent of conversion for Sec as might be expected based on our discussion above. However, the opposite pH reaction profile is observed for the conversion of Cys(5-Npys) to Cys-SH. At pH 4.5, only about 50% conversion can be achieved, even when the temperature is increased from 25 °C to 37 °C (compare S2 to S4 in Table 1). Increasing the reaction pH to 7 did increase the extent of conversion of Cys(5-Npys) to Cys-SH, but only after extended reaction time (24 hrs) and elevated temperature (37 °C ). Thus the ideal deprotection of Cys(5-Npys) occurs with 100 molar excess ascorbate at pH 7, 37 °C, and after 24 hours of incubation (reaction S8 in Table 1). These conditions are significantly different than that for Sec(5-Npys) and this difference might be exploited for orthogonal deprotection conditions in the future.

While we do not report further on the utility of this deprotection reaction here, we envision multiple applications of this chemistry. One such application is the creation of interchain disulfide, diselenide, or selenosulfide bonds as depicted in Figure 5. Such a strategy would be identical to the biotin-switch assay where a mild reductant is needed so as to avoid reduction of the intact disulfide bond [7, 8].

Figure 5.

Strategy for creating an interstrand selenosulfide bond between two peptide chains. Directed disulfide bond formation could occur (1), followed by conversion of Sec(Mob) to Sec(5-Npys) (2). Treatment with Asc would liberate the selenol, which could then be coupled to a Cys residue on a second peptide strand.

Another application should be in the generation of C-terminal thioesters from C-terminal Sec residues. Macmillan and coworkers attempted such an approach and reported that generation of the free selenol was difficult using a variety of conditions [15]. A cyclic peptide was synthesized from a linear precursor by generating a C-terminal thioester that originated from a C-terminal Sec(5-Npys) residue. The reported reaction conditions used for the synthesis of this cyclic peptide were 10% w/v MESNA, in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 5.8, with 5% w/v sodium ascorbate and 0.5% w/v TCEP [15]. Macmillan reported that the use of ascorbate helped to prevent deselenization of the peptide, which has also been reported by others [16, 17]. We hypothesize that TCEP could be eliminated from this reaction because ascorbate will directly reduce the Sec(5-Npys) group to the desired selenol, thus initiating the formation of the desired selenoester. Though we have not tested this hypothesis experimentally, it seems to be an attractive route for generating stable thioesters for use in native chemical ligation reactions.

Another application of this chemistry may be in the use of N-terminal Cys(5-Npys) and Sec(5-Npys) residues in peptide fragments that also contain a C-terminal thioester where three or more peptides segments are to be ligated together in native chemical ligation reactions [18, 19]. Protection of the N-terminal Cys is needed in such cases to avoid cyclization and polymerization of the peptide containing both a N-terminal Cys residue and a C-terminal thioester [20, 21].

In conclusion, we have developed a gentle and highly effective method for conversion of Sec(5-Npys) to Sec-SeH, and this deprotection has multiple applications as described above. This chemistry also works for deprotection of Cys(5-Npys), but higher concentrations of ascorbate and longer reaction times are required.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Solvents for peptide synthesis were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Fmoc-amino acids were purchased from RSsynthesis (Louisville, KY). 2-Chlorotrityl chloride resin SS (100–200 mesh) and 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole (HOAt) for solid-phase synthesis were purchased from Advanced ChemTech (Louisville, KY). L-Ascorbic acid sodium salt (99%) and triisopropylsilane (98%) were purchased from Acros Organics (Pittsburgh, PA). All other chemicals were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). The HPLC system was from Shimadzu with a Symmetry® C18 -5 μm column from Waters (4.6 x 150mm). Mass spectral analysis was performed on an Applied Biosystems QTrap 4000 hybrid triple-quadrupole/linear ion trap liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer (SciEx, Framingham, MA).

Peptide Syntheses

Fmoc-Sec(Mob)-OH was synthesized as reported previously [22] and used to synthesize peptide H-Pro-Thr-Val-Thr-Gly-Gly-Sec-Gly-OH (PTVTGGUG) as a test peptide that enabled us to explore the ascorbolysis strategy. Fmoc-Cys(Mob)-OH (NovaBiochem) was used to synthesize the following peptide: H-Pro-Thr-Val-Thr-Gly-Gly-Cys-Gly-OH (PTVTGGCG), the Cys-analog of our test peptide sequence. Both peptides were synthesized using solid-phase synthesis as described below. Peptides were synthesized on a 0.1 mmol scale using a glass vessel that was shaken with a model 75 Burrell wrist action shaker. Each batch used 300 mg of 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin SS (100–200 mesh, AdvancedChemtech). The first amino acid in the sequence was added directly to the resin, and the resin was successively capped using methanol. Subsequent amino acid couplings were performed using a 2-fold excess of Fmoc amino acid, N-methylmorpholine and HOBt (for all amino acids except Sec), or HATU and N,N-diisopropylcarbodiimide (for Sec only) in a dichloromethane (DCM) or dimethylformamide (DMF) solvent. Preactivation of the amino acid was not performed to minimize the racemization of L-cysteine and L-selenocysteine. These coupling conditions are essentially the same as those of Barany and co-workers, which were likewise used to minimize racemization of cysteine [23]. Couplings were deemed complete by ninhydrin testing after allowing the reaction to proceed for 1 hr. Removal of the Fmoc group between couplings was achieved via two 10 min agitations with a 20% piperdine/80% DMF mixture, fully covering the resin and rinsing between each deblocking step four times with DMF. Success of deblocking was monitored qualitatively using a ninhydrin test [24]. Removal of the final Fmoc protecting group completed the peptide synthesis.

Cleavage of the Cys-containing peptide from resin, along with deprotection of the side chain protecting groups, was done via a 2 hr reaction using a cleavage cocktail consisting of 2% thioanisol and 2,2′-dithiobis-5-nitropyridine (DTNP) dissolved in a 96% TFA/2% triisopropylsilane/2% water mixture [1]. This reaction mixture removes the Mob protecting group from Cys, replacing it with 5-Npys. For the Sec-containing peptide, the same reaction conditions and cleavage cocktail was used, but without the addition of thioanisole [1]. Following cleavage and deprotection, the resin was washed with TFA and DCM to remove any additional peptide, after which the volume of the cleavage solution was reduced by evaporation with nitrogen gas. The cleavage filtrate was then pipetted into cold, anhydrous diethyl ether, where the peptides were observed to precipitate. Centrifugation at 3000 rpm on a clinical centrifuge (International Equipment Co., Boston, MA) for 10 min pelleted the peptide, which was followed by two additional wash-precipitation cycles using TFA to dissolve the pellet and diethyl ether for precipitation. Peptides were then dissolved in a minimal amount of water and lyophilized. Both peptides were used without further purification.

Deprotection of S-5-nitro-2-pyridine-sulfenyl-cysteine (Cys(5-Npys)) and Se-5-nitro-2-pyridine-sulfenyl-selenocysteine (Sec(5-Npys)) by ascorbate

The lyophilized peptides were then dissolved in distilled/deionized water and divided into eight aliquots of 0.5 mL before treatment with ascorbate. Two ascorbate-containing buffers were prepared either at pH 4.5 and pH 7.0. Buffer A consisted of 40 mM ascorbate dissolved in 500 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH = 7.0 ± 0.1, and buffer B consisted of 40 mM ascorbate dissolved in 500 mM ammonium acetate buffer pH = 4.5 ± 0.1. Deprotection of the Cys-containing peptide was initiated by adding 0.5 mL of either buffer A or buffer B to the sample so that the total reaction volume was 1.0 mL, and the final concentration of ascorbate was 20 mM. At this concentration of ascorbate, the ratio of ascorbate to peptide was 100:1. Deprotection of the Sec-containing peptide was initiated by adding 0.1 mL of either buffer A or buffer B to 0.5 mL of the sample and then the reaction volume was adjusted to 1.0 mL by addition of either 0.4 mL of 500 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), or 500 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 4.5). At this concentration of ascorbate, the ratio of ascorbate to peptide was 5:1. The reactions were then allowed to proceed at either room temperature or 37 °C for either 4 hours or 24 hours according to Table 1.

Removal of 5-Npys by ascorbolysis monitored by HPLC

HPLC analysis of all samples was completed using a Shimadzu with a Symmetry® C18 -5μ column from Waters (4.6 x 150 mm). Aqueous and organic phases were 0.1% TFA in water (Buffer A) and 0.1% TFA in HPLC-grade acetonitrile (Buffer B), respectively. Beginning with 100% Buffer A, Buffer B was increased by 1% up to 50% over 50 min with a 1.4-mL/min gradient elution. Buffer B was then increased by 10% up to 100% over 5 min. This method was used for analysis of each sample. Peptide elution was monitored at both 214 nm and 254 nm.

Analysis of peptides by mass spectrometry

Each of the samples in Table 1 was subjected to analysis by mass spectrometry to determine the extent of deprotection. Samples were directly infused with a guard column at 10 μlL/min into a 100 μlL/min mobile phase flow consisting of 50/50 water/acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. The mobile phase flow was introduced into an Applied Biosystems QTrap 4000 hybrid triple-quadrupole/linear ion trap liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer operating in positive ESI mode. Mass spectra were collected in linear ion trap mode, scanning from m/z 200–1500.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant GM094172 to RJH. We also thank Douglas Masterson of the University of Southern Mississippi for critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

These studies were supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM094172 to RJH.

References

- 1.Harris KM, Flemer S, Jr, Hondal RJ. Studies on deprotection of cysteine and selenocysteine side-chain protecting groups. J Pept Sci. 2007;13:81–93. doi: 10.1002/psc.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schroll AL, Hondal RJ, Flemer S., Jr 2,2'-Dithiobis(5-nitropyridine) (DTNP) as an effective and gentle deprotectant for common cysteine protecting groups. J Pept Sci. 2012;18:1–9. doi: 10.1002/psc.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isidro-Llobet A, Álvarez M, Albericio F. Amino acid protecting groups. Chem Rev. 2009;109:2455–2504. doi: 10.1021/cr800323s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flemer S., Jr Selenol protecting groups in organic chemistry: special emphasis on selenocysteine Se-protection in solid phase peptide synthesis. Molecules. 2011;16:3232–3251. doi: 10.3390/molecules16043232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleming JE, Bensch KG, Schreiber J, Lohmann W. Interaction of ascorbate with disulfides. Z Naturforsch. 1983;38:859–861. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giustarini D, Dalle-Donne I, Colombo R, Milzani A, Rossi R. Is ascorbate able to reduce disulfide bridges? A cautionary note. Nitric Oxide. 2008;19:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Keszler A, Broniowska KA, Hogg N. Characterization and application of the biotin-switch assay for the identification of S-nitrosated proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:874–881. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forrester MT, Foster MW, Stamler JS. Assessment and application of the biotin switch technique for examining protein S-nitrosylation under conditions of pharmacologically induced oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13977–13983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panduranga V, Prabhu G, Kumar R, Basavaprabhu, Sureshbabu VV. A facile one pot route for the synthesis of imide tethered peptidomimetics. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;14:556–63. doi: 10.1039/c5ob01708d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell NJ, Malins LR, Liu X, Thompson RE, Chan B, Radom L, Payne RJ. Rapid additive-free selenocystine-selenoester peptide ligation. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:14011–14014. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aihara K, Yamaoka K, Naruse N, Inokuma T, Shigenaga A, Otaka A. One-pot/sequential native chemical ligation using photocaged crypto-thioester. Org Lett. 2016;18:596–599. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saeeduddin, Khanzada AW, Mufti AT. Determination of equilibrium constant of ascorbic acid and benzoic acid at different temperature and in aqueous and non-aqueous media. Pak J Pharm Sci. 1996;9:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabanal F, DeGrado WF, Dutton PL. Use of 2,2'-dithiobis(5-nitropyridine) for the heterodimerization of cysteine containing peptides. Introduction of the 5-nitro-2-pyridine sulfenyl group. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:1347–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brocklehurst K, Little G. Reactions of papain and of low-molecular-weight thiols with some aromatic disulphides. 2,2'-Dipyridyl disulphide as a convenient active-site titrant for papain even in the presence of other thiols. Biochem J. 1973;133:67–80. doi: 10.1042/bj1330067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams AL, Macmillan D. Investigation of peptide thioester formation via N→Se acyl transfer. J Pept Sci. 2013;19:65–73. doi: 10.1002/psc.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuda S1, Yoshiya T1, Mochizuki M1, Nishiuchi Y. Synthesis of cysteine-rich peptides by native chemical ligation without use of exogenous thiols. Org Lett. 2015;17:1806–1809. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rohde H, Schmalisch J, Harpaz Z, Diezmann F, Seitz O. Ascorbate as an alternative to thiol additives in native chemical ligation. Chembiochem. 2011;12:1396–1400. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raibaut L, Ollivier N, Melnyk O. Sequential native peptide ligation strategies for total chemical protein synthesis. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:7001–7015. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35147a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takenouchi T, Katayama H, Nakahara Y, Nakahara Y, Hojo H. A novel post-ligation thioesterification device enables peptide ligation in the N to C direction: synthetic study of human glycodelin. J Pept Sci. 2014;20:55–61. doi: 10.1002/psc.2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canne LE, Botti P, Simon RJ, Chen Y, Dennis EA, Kent SB. Chemical protein synthesis by solid phase ligation of unprotected peptide segments. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8720–8727. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brik A, Keinan E, Dawson PE. Protein synthesis by solid-phase chemical ligation using a safety catch linker. J Org Chem. 2000;65:3829–3835. doi: 10.1021/jo000346s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hondal RJ, Raines RT. Semisynthesis of proteins containing selenocysteine. Methods Enzymol. 2002;347:70–83. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)47009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han Y, Albericio F, Barany G. Occurrence and minimization of cysteine racemization during stepwise solid-phase peptide synthesis. J Org Chem. 1997;62:4307–4312. doi: 10.1021/jo9622744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser E, Colescott RL, Bossinger CD, Cook PI. Color test for detection of free terminal amino groups in the solid-phase synthesis of peptides. Anal Biochem. 1970;34:595–598. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]