Abstract

Mitochondria is an attractive target to deliver anticancer drugs. We have synthesized a cationic triphenylphosphonium ion conjugated fluorescent polymer which self-assembles into nanosized polymersomes and targets the encapsulated anticancer drug doxorubicin to cancer cell mitochondria.

Graphical Abstract

We have synthesized a fluorescent polymer which self-assembles into polymersomes and targets the encapsulated anticancer drug to cancer cell mitochondria.

Mitochondria govern the cellular electron transport and power dynamics. In rapidly multiplying cancer cells, mitochondria assist in the proliferation, progression, and development of resistance to the treatment.1 Activation of the mitochondrial pro-apoptotic assembly overcomes multidrug resistance in cancer cells.2, 3, 3 The enzyme topoisomerase II, found in the nucleus and mitochondria, plays a significant role in cellular replication. Recent studies have demonstrated that the anticancer drug doxorubicin, in addition to inhibiting topoisomerase II, affects the membrane integrity and DNA synthesis in the mitochondria.4 Hence, targeting mitochondria with doxorubicin is a promising approach for cancer therapy.5

The inner membrane of mitochondria has considerably more negative charges compared to the outer membrane.6 The triphenylphosphonium cation (TPP) targets and traverses the negatively-charged mitochondrial membranes.7 Conjugation of drugs or imaging agents with TPP transports them inside the mitochondria.8, 9a,5b

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) coating renders nanoparticles long-circulating and allows them to infiltrate into the tumour microenvironment through the leaky vasculature.10 Theranostic nanoparticles permit simultaneous imaging to ensure site-specific drug delivery.11 Amphiphilic block copolymers with appropriate hydrophilic-hydrophobic balance self-assemble into polymersomes.12 These vesicles encapsulate hydrophilic drugs in the aqueous core and hydrophobic drugs in the bilayer.13 Herein, we have synthesized a mitochondria-targeting, fluorescent analogue of TPP and conjugated it to the amphiphilic polymer poly (lactic acid)-co-poly (ethylene glycol) (PLA–PEG). The resultant polymer self-assembles into polymersomes in an aqueous buffer. We have used the polymeric vesicles to deliver the anticancer drug doxorubicin successfully into the mitochondria, resulting in significantly reduced viability of cultured pancreatic cancer cell spheroids.

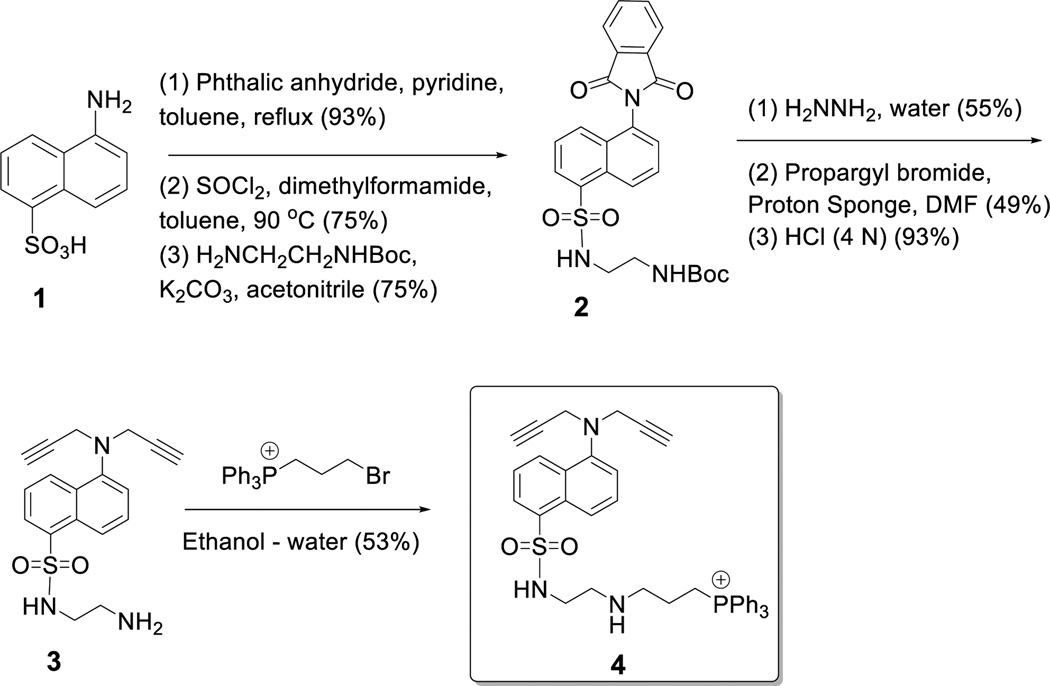

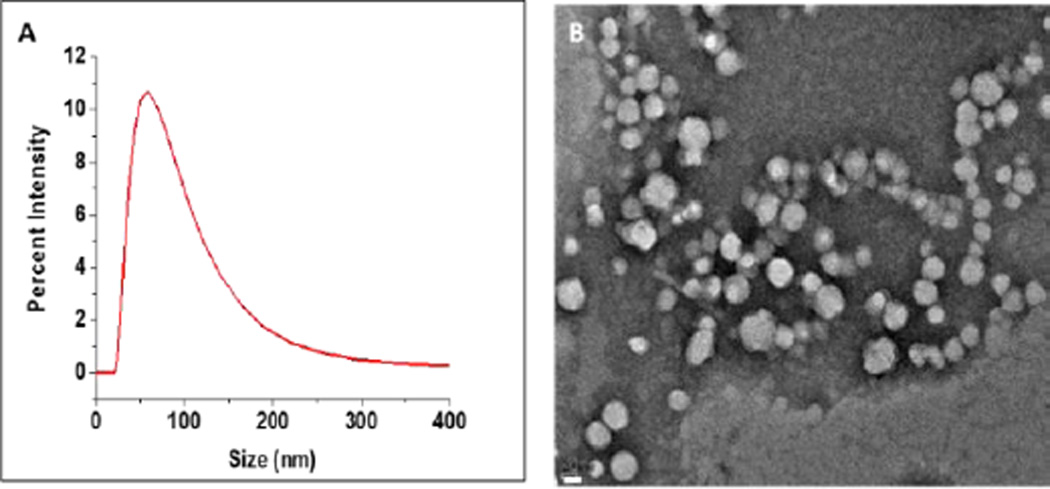

We synthesized the fluorescent mitochondria targeting compound 4 starting from the commercially available 5-aminonaphthalene sulfonic acid (Compound 1, Scheme 1 and Electronic Supplemental Information). The amino group was protected as phthalimide, the sulfonyl group was converted to the acid chloride and reacted with mono-protected ethylenediamine. Deprotection of the phthalimide group and reaction with propargyl bromide afforded the tertiary amine derivative 3. We were unable to optimize the reaction conditions such that only one propargyl group is incorporated. Subsequent deprotection of the t-butyloxycarbonyl group and reaction with triphenylphosphinoethyl bromide produced the fluorescent, mitochondrial targeting compound 4. We conjugated 4 with the synthesized PEG2000–PLA5000–N3 employing the Cu2+–catalysed [2+3]-cycloaddition reaction (Scheme 2).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the fluorescent, mitochondria targeting compound 4.

Scheme 2.

Conjugation reaction between the fluorescent mitochondria targeting compound 4 and the polymer PLA-PEG-N3.

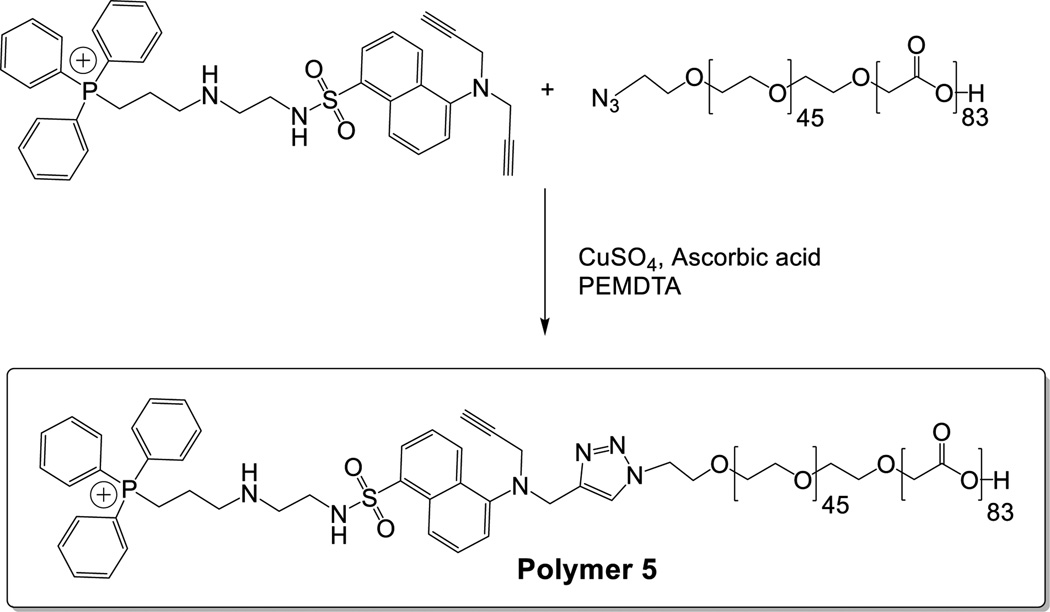

We prepared the polymersomes incorporating 90 mol% of the commercially available poly (L-lactic acid) PLLA5000 – PEG2000 and the synthesized mitochondria targeting polymer 5 (Scheme 2, 10 mol%) employing the solvent exchange method.14 The size of polymersomes was analysed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and transmission electron microscopic (TEM) (Figure 1). DLS analysis of prepared polymersomes indicated the size as 89 ± 6 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.3. Similar results were observed with TEM imaging. To demonstrate the bilayer structure, we prepared giant polymersomes and encapsulated the dye FM1-43 in the membrane following a reported procedure.15 Confocal fluorescence microscopic studies indicated the bilayers of the polymersomes (Figure S7, Electronic Supplemental Information). We observed that the high positive Zeta potential of the mitochondria targeting compound (46.5 ± 2.8 mV) was reduced (19.6 ± 0.8 mV) upon conjugation with the PLA-PEG polymer. The polymersomes had even lower Zeta potential (9 ± 0.8 mV, Electronic Supplementary Information).

Figure 1.

Size distribution of the prepared polymersomes by DLS (A) and TEM (B) (scale bar: 20 nm).

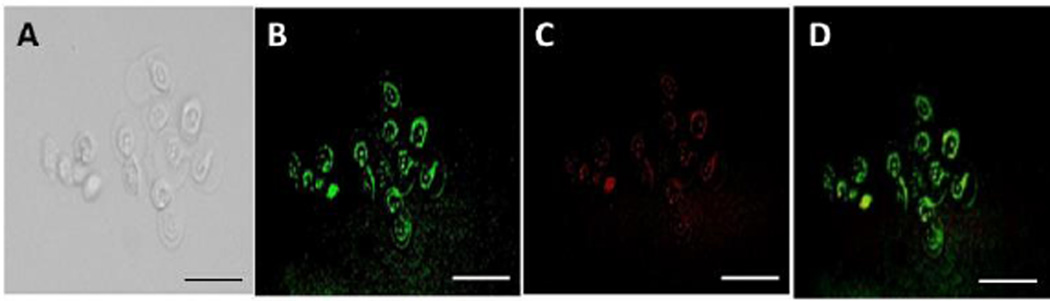

We prepared buffer-encapsulated polymersomes to determine the cellular localization. The BxPC-3 pancreatic cancer cells were seeded in a 6-well plate and then treated with the buffer encapsulated, fluorescent, mitochondria targeting polymersomes for varying time intervals. The cellular mitochondria were stained with the dye Milo view following the manufacturer’s protocol. We imaged the cells using a fluorescence microscope to determine the localization of the targeted polymersomes. We observed the fluorescence from mitochondria using a tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC) filter and the fluorescence from the polymersomes using the 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) filter. Overlapping fluorescence from the MitoView Red and the polymersomes confirmed mitochondrial localization of the vesicles (Figure 2). We observed complete overlap of the green and red colours after 2 hours of incubation of the cells with the polymersomes (Figure 2, Panel D).

Figure 2.

Bright-field (Panel A) and fluorescence microscopic (Panel B) images of the BxPC-3 cells incubated with the mitochondria-targeted polymersomes. Mitochondria were stained with MitoView Red (Panel C). Panel D shows the overlap of the green and red fluorescence, indicating mitochondrial localization of the polymersomes (scale bar: 50 µm).

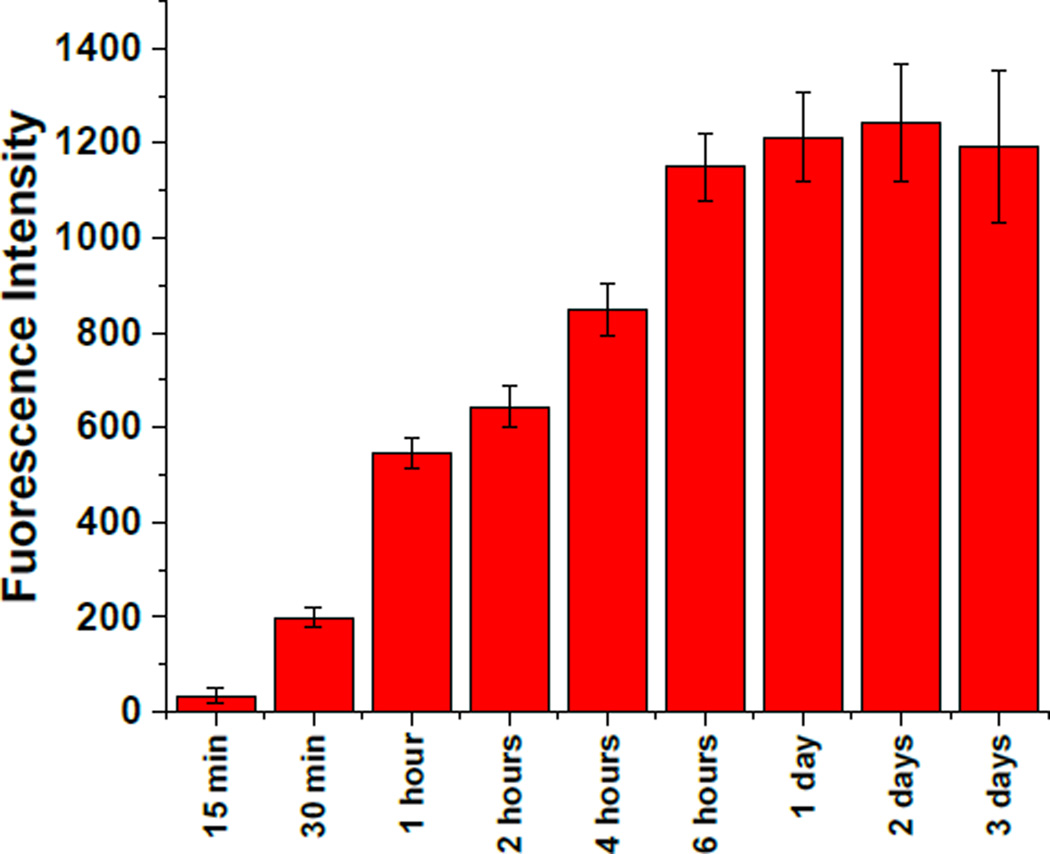

To optimize the mitochondrial localization, we cultured 108 BxPC-3 cells in flasks and incubated them with carboxyfluorescein-encapsulated polymersomes. After different time intervals (15 min, 30 min, 1 hour, 4 hours, 6 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours), we washed the cells, isolated the mitochondria (using manufacturer’s protocol, Electronic Supplemental Information), and centrifuged at 20,000 g to form a pellet. Fluorescence intensity in the supernatant (mitochondrial internalized dye) was measured at the emission wavelength of 515 nm (excitation: 485 nm). We observed the maximum fluorescence intensity after 6 hours of incubation (Figure 3). Longer treatment did not show significantly increase the emission intensity – indicating that the polymersomes were internalized in the BxPC-3 cells within 6 hours (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Fluorescence emission intensity of carboxyfluorescein (Excitation: 485 nm, Emission: 515 nm) in the supernatant as a function of time (n = 3).

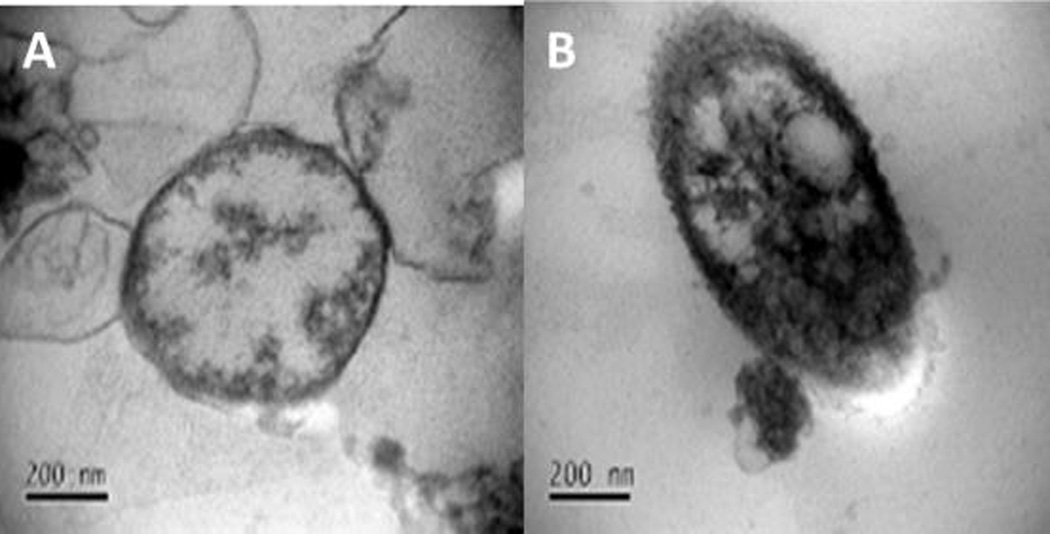

To further confirm the internalization and the effect of the treatment on the cellular mitochondria, we prepared the polymersomes encapsulating citrate buffer (20 mM, pH 4) suspended in HEPES buffer (25 mM, pH 7.4). The BxPC-3 cells (108) were treated with the drug encapsulated polymersomes for 2 hours. Subsequently, we washed the cells, isolated the mitochondria using a commercially-available mitochondria isolation kit (Electronic Supplemental Information), and imaged them using TEM. We observed different morphology for the mitochondria when the cells were treated with buffer encapsulated polymersomes compared to the untreated control (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

TEM images showing the isolated mitochondria before (A) and after (B) treatment with buffer encapsulated polymersomes.

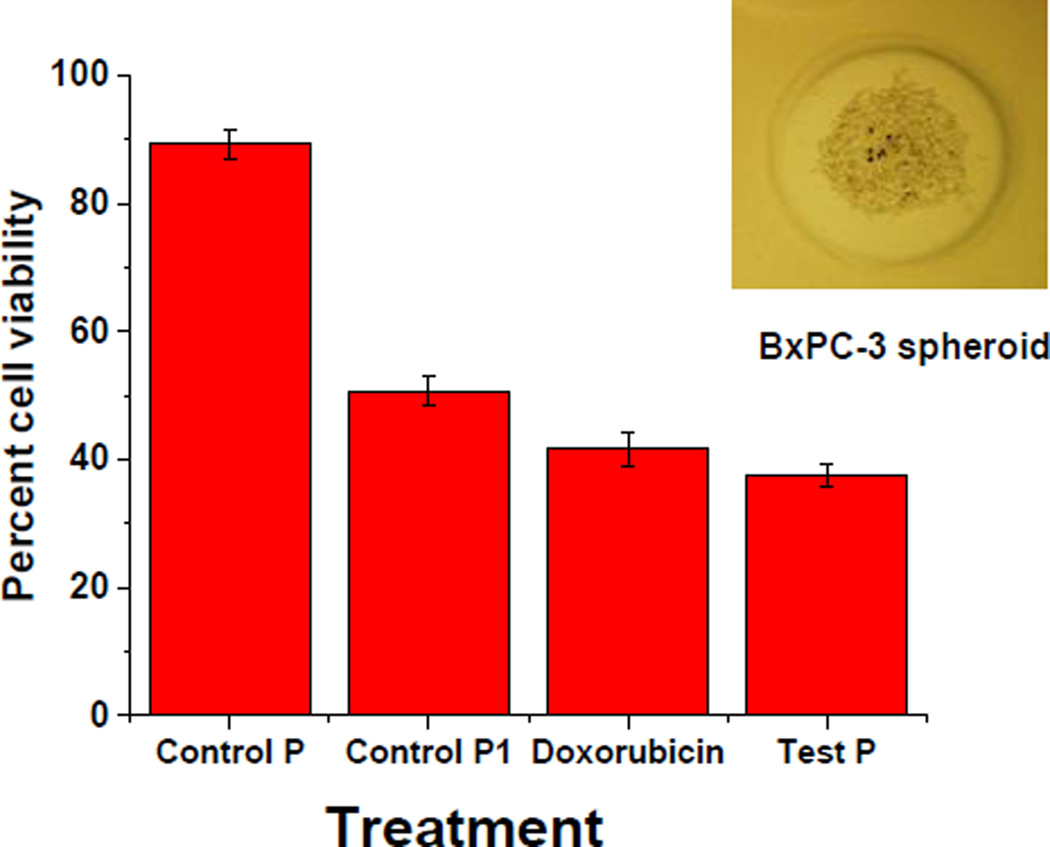

After confirming the mitochondrial localization, we encapsulated the anticancer drug doxorubicin (efficiency: 40 ± 8%) in the polymersomes by the pH-gradient method (Electronic Supplemental Information). The polymersomes are intended to target the mitochondria, localize inside, and then release the encapsulated drug by diffusion or degradation. No stimuli responsive material is used in these polymersomes. Subsequently, we cultured the pancreatic cancer cells (BxPC-3) as three-dimensional spheroids using agarose scaffolds (prepared from molds supplied by Microtissues, Electronic Supplemental Information). We treated the 10-day old cell spheroids with doxorubicin (10 µM), polymersomes encapsulating doxorubicin (equivalent to 10 µM) with and without the mitochondria targeting polymer 5. The cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. We disrupted the treated cell spheroids with recombinant trypsin enzyme (TryPLE). The disrupted spheroids were then cultured as monolayers, and the viability was determined using the Alamar Blue assay.16 We observed that the spheroids treated with mitochondria-targeted, doxorubicin-encapsulated polymersomes showed decreased cell viability compared with the free drug or the drug-encapsulated, non-targeting vesicles (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The viability of the BxPC-3 cell spheroids treated with doxorubicin (10 µM), control polymersomes devoid of mitochondria targeting molecule (Control P1), and mitochondria-targeted test polymersomes (Test P) encapsulating an equivalent amount of doxorubicin (n = 8). A typical image of a cultured, 10-day old BxPC-3 spheroid is shown in the inset (diameter: 150 µm, magnification: 5X).

In summary, we have successfully synthesized a fluorescent triphenylphosphonium (TPP) compound containing two alkyne groups and conjugated it to an amphiphilic block copolymer. The resultant polymer was successfully incorporated into polymersomes. The TPP moiety allowed mitochondrial localization of the polymersomes in pancreatic cancer cells. We also imaged the mitochondria employing the fluorescence emission from the dansyl groups. Targeting of doxorubicin-encapsulated vesicles to the mitochondria significantly decreased the viability of the cultured cancer cell spheroids compared to the non-targeted counterparts. The PEG polymer on the surface of these polymersomes is expected to render them long circulating and suitable for targeted delivery of anti-cancer drugs.17 We also note that the scope of our polymersomes is not limited to anticancer drug delivery only. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been observed in various other chronic ailments, such as Alzheimer’s disease and type II diabetes.18, 19 Our fluorescent, mitochondria targeting polymersomes can find applications in imaging or targeting drugs to mitochondria of the cells with mitochondrial dysfunction.

Supplementary Material

LIVE SUBJECT STATEMENT.

The pancreatic cancer cells used in the study were purchased from American Tissue Culture Consortium (www.atcc.org). The cellular experiments were approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee (protocol B16011) and were conducted in compliance with the laws and policies of the North Dakota State University.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NSF grant DMR 1306154 and NIH grant 1 R01GM 114080 to SM. PSK was supported by a Doctoral Dissertation Award (IIA-1355466) from the North Dakota EPSCoR (National Science Foundation). TEM material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0923354.

References

- 1.Dorward A, Sweet S, Moorehead R, Singh G. Journal of bioenergetics and biomembranes. 1997;29:385–392. doi: 10.1023/a:1022454932269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joza N, Susin SA, Daugas E, Stanford WL, Cho SK, Li CY, Sasaki T, EliaSasaki AJ, Cheng H-YM, Ravagnan L. Nature. 2001;410:549–554. doi: 10.1038/35069004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fulda S, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2010;9:447–464. doi: 10.1038/nrd3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashley N, Poulton J. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2009;378:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’brien M, Wigler N, Inbar M, Rosso R, Grischke E, Santoro A, Catane R, Kieback D, Tomczak P, Ackland S. Annals of oncology. 2004;15:440–449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scaduto RC, Grotyohann LW. Biophysical journal. 1999;76:469–477. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77214-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy MP. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics. 2008;1777:1028–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy MP, Smith RA. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47:629–656. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickinson BC, Srikun D, Chang CJ. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2010;14:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otsuka H, Nagasaki Y, Kataoka K. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2012;64:246–255. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie J, Lee S, Chen X. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2010;62:1064–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng F, Zhong Z, Feijen J. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:197–209. doi: 10.1021/bm801127d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Discher DE, Ahmed F. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2006;8:323–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsden HR, Gabrielli L, Kros A. Polymer Chemistry. 2010;1:1512–1518. [Google Scholar]

- 15.SangáKim M, SungáLee D. Chemical Communications. 2010;46:4481–4483. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkarni PS, Haldar MK, Nahire RR, Katti P, Ambre AH, Muhonen WW, Shabb JB, Padi SK, Singh RK, Borowicz PP. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2014;11:2390–2399. doi: 10.1021/mp500108p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Murray JC. Pharmacological reviews. 2001;53:283–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin MT, Beal MF. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowell BB, Shulman GI. Science. 2005;307:384–387. doi: 10.1126/science.1104343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.