Significance

Pathogens, and antipathogen behavioral strategies, affect myriad aspects of human behavior. Recent findings suggest that antipathogen strategies relate to political attitudes, with more ideologically conservative individuals reporting more disgust toward pathogen cues, and with higher parasite stress nations being, on average, more conservative. However, no research has yet adjudicated between two theoretical accounts proposed to explain these relationships between pathogens and politics. We find that national parasite stress and individual disgust sensitivity relate more strongly to adherence to traditional norms than they relate to support for barriers between social groups. These results suggest that the relationship between pathogens and politics reflects intragroup motivations more than intergroup motivations.

Keywords: political ideology, pathogens, disgust, culture, evolutionary psychology

Abstract

People who are more avoidant of pathogens are more politically conservative, as are nations with greater parasite stress. In the current research, we test two prominent hypotheses that have been proposed as explanations for these relationships. The first, which is an intragroup account, holds that these relationships between pathogens and politics are based on motivations to adhere to local norms, which are sometimes shaped by cultural evolution to have pathogen-neutralizing properties. The second, which is an intergroup account, holds that these same relationships are based on motivations to avoid contact with outgroups, who might pose greater infectious disease threats than ingroup members. Results from a study surveying 11,501 participants across 30 nations are more consistent with the intragroup account than with the intergroup account. National parasite stress relates to traditionalism (an aspect of conservatism especially related to adherence to group norms) but not to social dominance orientation (SDO; an aspect of conservatism especially related to endorsements of intergroup barriers and negativity toward ethnic and racial outgroups). Further, individual differences in pathogen-avoidance motives (i.e., disgust sensitivity) relate more strongly to traditionalism than to SDO within the 30 nations.

The costs imposed by pathogens on their hosts have spurred the evolution of complex antipathogen defenses, many of which are behavioral (1, 2). In humans, such defenses range from the proximate avoidance of pathogen cues to the execution of complex rituals, often with far-reaching consequences (3). At the individual level, functionally specialized psychological mechanisms detect pathogen cues and motivate avoidance of physical contact with pathogens [e.g., via the emotion of disgust (4)]. These mechanisms, which have been collectively referred to as the behavioral immune system, influence, among other things, mate preferences (5, 6), dietary preferences (7), and person perception (8) (summarized in ref. 9). At the cultural level, many rules and rituals putatively function to mitigate infection risk, including those concerning food preparation and consumption (e.g., 10, 11), coughing and sneezing, and the use of a particular hand in ablutions (and little else).

Some of the most provocative findings in the behavioral immune system literature suggest that political attitudes are influenced both by individual motivations to avoid pathogens and by the presence of pathogens within an ecology. At the individual level, the degree to which people are disgusted by pathogen cues and wary of infection-risky situations relates to a number of politically relevant variables, including political party preference, openness to experience, and collectivism (summarized in ref. 12). At the cultural level, nations with greater infectious disease burdens (i.e., parasite stress) are governed by more authoritarian regimes and are more religious, more collectivistic, and less open to experience (13–17), all of which are hallmarks of conservative ideology. Two distinct hypotheses, one of which is fundamentally an intragroup account and one of which is fundamentally an intergroup account, have been advanced to explain these empirical patterns (13, 18, 19). The first, which we refer to as a traditional norms account, is based on the assumption that some local rules and rituals (e.g., how foods are prepared and stored, which meats are acceptable, which hand one eats with) evolve culturally to neutralize local pathogen threats. This intragroup account suggests that departures from traditional norms increase individuals' risk of infection, so more pathogen-avoidant individuals favor ideological positions that encourage adherence to traditional values (11, 20, 21).

The second hypothesis, which we refer to as an outgroup-avoidance account, is based on the assumption that individuals develop greater resistance to locally prevalent pathogens than to pathogens endemic to foreign ecologies, perhaps even those ecologies close enough to reach by foot (14, 16). This intergroup account holds that contact with outgroup members (who carry pathogens that individuals might have less immunity against) is more likely to result in infectious disease than is contact with ingroup members. Consequently, more pathogen-avoidant individuals favor ideological positions that minimize intergroup pathogen transmission.

Which of these two hypotheses better explains the relationship between the behavioral immune system and ideology? Given that conservatism is characterized both by stronger preferences for ethnic, racial, and national ingroups (vs. outgroups) and by greater adherence to traditional cultural norms (22), existing data have been interpreted as supporting both hypotheses. Of course, both accounts could be correct: Both intergroup and intragroup motivations could underlie the observed relationships between pathogens and politics. However, no work has yet aimed to generate and test competing predictions derived from these two hypotheses. We aim to fill this gap here. To do so, we depart from standard practice in this area, which has interpreted several different constructs as reflecting a single dimension of ideology. For example, a recent meta-analysis of the relationship between the behavioral immune system and conservatism treated diverse constructs—including right-wing authoritarianism, collectivism, religiosity, and social dominance orientation (SDO)—as interchangeable manifestations of social conservatism (12). In the current investigation, we consider how the above-described intragroup and intergroup accounts can be used to make distinct predictions regarding the relationship between the behavioral immune system and two dimensions of ideology: traditionalism and SDO.

Dimension-Specific Relationships Between Pathogens and Ideology

Political psychologists suggest that ideology can be broadly categorized along two dimensions (22, 23), one of which is conceptualized as relating more to intragroup attitudes and the other of which is conceptualized as relating more to intergroup attitudes (24). The first (intragroup) dimension is characterized by favoring adherence to versus departures from social traditions [frequently operationalized as right wing authoritarianism and, specifically, the traditionalism facet of right wing authoritarianism (25)]. The second (intergroup) dimension is characterized by favoring versus rejecting (hierarchical) boundaries between groups [frequently operationalized as SDO (26)].

Although traditionalism and SDO are generally positively correlated, they relate differently to social values (27–29). Whereas traditionalism relates strongly to religiosity (25), a key variable in the behavioral immune system and ideology literature, SDO relates only weakly to conformity and adherence to religious orthodoxy (30, 31). Moreover, although both traditionalism and SDO relate to prejudices, they relate to prejudices toward different targets. Relative to SDO, traditionalism especially relates to prejudice toward the types of individuals who violate traditional social norms, including prostitutes, atheists, homosexuals, and drug users (32). In contrast, SDO especially relates to prejudice toward individuals possessing cues to different ecological origin (e.g., skin color), including white Americans’ prejudice toward blacks (33) and New Zealanders’ prejudice toward Africans, Asians, and Maori (31, 32). Reactions to immigrants (i.e., outgroup members hailing from foreign ecologies) can further highlight differences between SDO and traditionalism. Traditionalism relates to antiimmigrant sentiments when immigrants are pictured as failing to adopt local cultures rules and rituals; in contrast, SDO relates to antiimmigrant sentiment when immigrants are pictured as assimilating and, hence, increasing contact between groups (34).

Given the above considerations, the intragroup (traditional norms) hypothesis implies that pathogen-avoidance motives should relate to traditionalism, but not necessarily SDO. The intergroup (outgroup-avoidance) hypothesis implies a different prediction. Because SDO relates more strongly to prejudice toward individuals from foreign ecologies (e.g., immigrants, individuals from a different ethnic background), whereas traditionalism relates more strongly to prejudice toward nontraditional subgroups within a common ecology (e.g., homosexuals, atheists) (31, 32, 34), the outgroup-avoidance hypothesis implies that pathogen-avoidance motives should relate to SDO, but not necessarily to traditionalism.

Testing Competing Behavioral Immune System Hypotheses Within and Across Nations

Although results at individual and societal levels have been interpreted as providing converging evidence for behavioral immune system hypotheses of ideology, they differ in two important ways, each of which has implications for the hypotheses described above. First, almost all studies reporting individual-level relationships between the behavioral immune system and ideology have been conducted using North American samples. For example, 23 of the 24 studies considered in a recent meta-analysis of the relationship between individual differences in pathogen-avoidance motives and social conservatism used US or Canadian samples (12). In contrast, studies at the societal level have necessarily tested group-level relationships between parasite stress and ideology across nations or states. Second, whereas individual-level studies have used self-report instruments to assess pathogen-avoidance motives, cross-cultural studies have used national parasite stress estimates, with the assumption that greater ecological parasite stress leads to stronger individual-level motivations to avoid pathogens (35, 36). For example, in describing the potential relationship between variables measured at the individual level (e.g., disgust sensitivity) and societal level (i.e., parasite stress), Fincher and Thornhill (14) argue, “Our approach suggests that the relationship between infectious disease and religiosity will be mediated… by disgust and contamination sensitivity” (p. 78).

No research has yet tested (i) whether the individual-level relationships between pathogen-avoidance motives and dimensions of ideology (including traditionalism and SDO) found in North America samples replicate across cultures; (ii) whether individuals in higher parasite stress nations indeed score higher on instruments designed to measure pathogen-avoidance motives (e.g., disgust sensitivity); and (iii) whether individual-level pathogen-avoidance motives mediate any relationship between country-level parasite stress and traditionalism, SDO, or both. The current research aims to address these questions by measuring traditionalism, SDO, and (pathogen) disgust sensitivity across a number of nations that vary in parasite stress. In doing so, we test competing predictions made by the two behavioral immune system hypotheses of ideology described above, and we do so at both the national level and the individual level. We then use the same dataset (Dataset S1) to test the common assumption that higher parasite stress at the country level is associated with stronger pathogen-avoidance motives at the individual level. In total, we report results using a sample of 11,501 individuals from 30 nations (details are provided in Table 1).

Table 1.

Survey language(s), percentage male, mean age in years, and bivariate correlations for samples in each nation surveyed

| Country | Language(s) | n | Male | Age | rT_DS | r′T_DS | rSDO_DS | r′SDO_DS |

| Argentina (AR) | Spanish | 827 | 64 | 34 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Australia (AU) | English | 300 | 48 | 31 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Belgium (BE) | Dutch | 448 | 46 | 23 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Bosnia & Herzegovina (BA) | Bosnian and Croatian | 326 | 30 | 28 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Brazil (BR) | Portuguese | 288 | 46 | 23 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Canada (CA) | English | 307 | 42 | 35 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.16 | −0.22 |

| Chile (CL) | Spanish | 262 | 49 | 28 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| China (CN) | Simplified Chinese | 377 | 10 | 21 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.20 |

| Croatia (HR) | Croatian | 554 | 23 | 30 | 0.08 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.04 |

| Denmark (DK) | Danish | 126 | 40 | 24 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| Finland (FI) | Finnish | 190 | 42 | 41 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| France (FR) | French | 266 | 29 | 23 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.21 |

| Germany (DE) | German | 374 | 47 | 32 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Greece (GR) | Greek | 317 | 27 | 32 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| India (IN) | Hindi and English | 504 | 57 | 23 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.14 |

| Ireland (IE) | English | 150 | 52 | 32 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.23 |

| Israel (IL) | Hebrew | 339 | 38 | 34 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Japan (JP) | Japanese | 394 | 53 | 32 | 0.11 | 0.17 | −0.04 | −0.06 |

| Netherlands (NL) | Dutch | 574 | 42 | 35 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| New Zealand (NZ) | English | 595 | 27 | 29 | 0.11 | 0.15 | −0.06 | −0.09 |

| Poland (PL) | Polish | 210 | 31 | 28 | −0.09 | −0.12 | −0.05 | −0.09 |

| Serbia (RS) | Serbian | 402 | 31 | 29 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Singapore (SG) | English | 239 | 48 | 25 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Slovakia (SK) | Slovak | 338 | 33 | 32 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Republic of Korea (KR) | Korean | 137 | 42 | 21 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| Spain (ES) | Spanish | 699 | 33 | 33 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sweden (SE) | English | 117 | 45 | 30 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.30 | 0.41 |

| Turkey (TR) | Turkish | 1,082 | 50 | 34 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| United Kingdom (UK) | English | 276 | 27 | 28 | 0.18 | 0.25 | −0.05 | −0.07 |

| United States (US) | English | 483 | 62 | 30 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Total | 11,501 | 42 | 30 | 0.10 (0.07–0.12) | 0.14 (0.10–0.18) | 0.04 (0.02–0.06) | 0.06 (0.03–0.10) |

The r′ statistics are disattenuated for unreliability. The total (bottom row) includes meta-analyzed correlations and 95% CIs. DS, disgust sensitivity; SDO, social dominance orientation; T, traditionalism.

Results

Traditionalism.

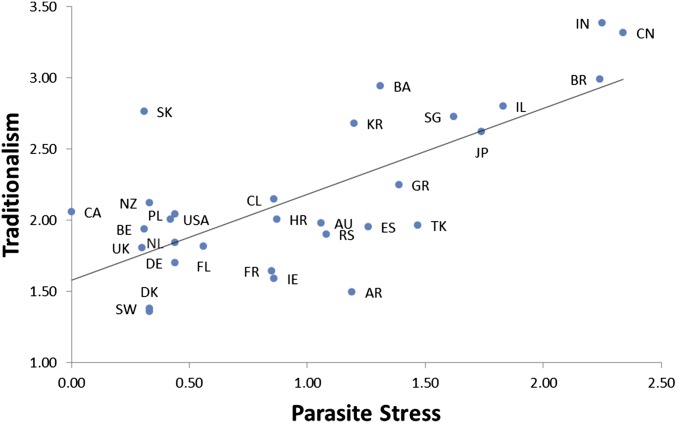

The intragroup, traditional norms hypothesis predicts a relationship between traditionalism and pathogen-avoidance motives. Results at both the individual and national levels were consistent with this account. Individuals in nations with greater parasite stress were more traditional [t(26.54) = 4.16, P < 0.001; Fig. 1]; to illustrate, nations’ average traditionalism scores correlated strongly with parasite stress (r = 0.70, P < 0.001). Notably, these results are similar to the results reported in previous analyses of the relationship between parasite stress and archival estimates of collectivism across 52 and 70 nations, which yielded correlations of r = 0.73 and r = 0.63, respectively (13). Within nations, disgust sensitivity also related to traditionalism [t(25.97) = 8.46, P < 0.001], independent of national parasite stress. A random effects meta-analysis showed the correlation between disgust sensitivity and traditionalism to be r = 0.10 [95% CI (0.07, 0.12)]. Analyses on correlations disattenuated for unreliability yielded similar results [r = 0.14, 95% CI (0.10, 0.18)].

Fig. 1.

The scatterplot displays the relationship between national parasite stress and traditionalism (r = 0.70). Each data point [labeled with a two-letter country code (abbreviations defined in Table 1)] represents a nation's mean traditionalism, controlling for sample demographic characteristics (age and sex).

SDO.

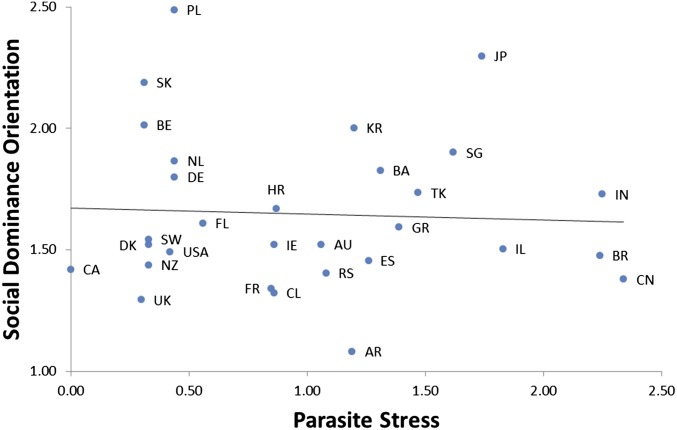

The intergroup, outgroup-avoidance account predicts a relationship between SDO and pathogen-avoidance motives. Results were not consistent with this prediction at the nation level, with individuals in higher parasite stress nations scoring no higher on SDO [t(25.19) = 0.12, P = 0.91; Fig. 2], and with the correlation between national parasite stress and SDO close to zero (and directionally opposite to predictions) (r = −0.06, P = 0.75). Within nations, disgust sensitivity was indeed related to SDO [t(23.57) = 6.52, P < 0.001]. However, the random effects metaanalysis indicated that the correlation between disgust sensitivity and SDO was close to zero [r = 0.04, 95% CI (0.02, 0.06)]. Analyses on disattenuated correlations yielded similar results [r = 0.06, 95% CI (0.03, 0.10)]. Notably, these 95% CIs did not overlap with the 95% CIs for the relationship between disgust sensitivity and traditionalism.

Fig. 2.

The scatterplot displays the relationship between national parasite stress and SDO (r = −0.06). Each data point [labeled with a two-letter country code (abbreviations defined in Table 1)] represents a nation's mean SDO, controlling for sample demographic characteristics (age and sex).

Cross-National Variability in Disgust Sensitivity.

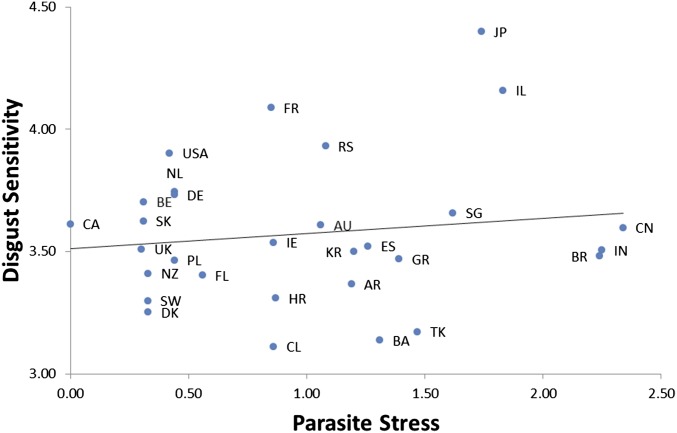

Although we observed variation in disgust sensitivity across nations [τ00 = 0.09, χ2(1) = 47.41, P < 0.001], this variability was unrelated to parasite stress [t(26.18) = 1.12, P = 0.27; Fig. 3]. However, results suggested that the disgust sensitivity instrument had similar validity across samples. In addition to observing a relationship between disgust sensitivity and traditionalism across nations, we replicated previously reported sex-related differences in disgust sensitivity (37, 38), with women consistently scoring higher than men across nations [t(20.73) = 16.46, P < 0.001, meta-analyzed d = 0.41, 95% CI (0.36, 0.45)].

Fig. 3.

The scatterplot displays the relationship between national parasite stress and disgust sensitivity (r = 0.18). Each data point [labeled with a two-letter country code (abbreviations defined in Table 1)] represents a nation's mean disgust sensitivity, controlling for sample demographic characteristics (age and sex).

Discussion

Several lines of evidence point to a relationship between pathogens and politics (9, 12). Here, we aimed to clarify the nature of this relationship by generating competing predictions using two behavioral immune system hypotheses of conservatism. The traditional norms account predicts that pathogen-avoidance motives should relate to traditionalism, which, relative to SDO, more strongly relates to intragroup attitudes, such as endorsements of traditional rules and rituals and antipathy toward within-group deviants. In contrast, the outgroup-avoidance account predicts that pathogen-avoidance motives should relate to SDO, which, relative to traditionalism, more strongly relates to intergroup attitudes, such as negative attitudes toward ethnic outgroups and support for barriers between groups. Results supported the traditional norms account over the outgroup-avoidance account, with national parasite stress relating strongly to traditionalism but not to SDO. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of individual-level relationships within the 30 sampled nations revealed that disgust sensitivity relates more strongly to traditionalism than to SDO. Indeed, whereas the traditionalism-disgust sensitivity relationship was of a magnitude similar to that observed in a large recent study in the United States (39), the SDO-disgust sensitivity relationship, while nonzero, was negligible.

Results also helped to clarify the relationship between national parasite stress and individual pathogen-avoidance motives. We found no support for the notion that individuals living in more pathogen-dense countries are more disgust-sensitive. This null result may be understood by considering both the benefits and the costs of investing in pathogen avoidance. Although greater disgust sensitivity steers individuals away from cues to pathogens, it also constrains dietary, sexual, and social contact opportunities (4, 40). If pathogens are ubiquitous enough that investments in avoidance do not decrease infection—at least not enough to offset the benefits of behaviors that pose some infection risk—then individuals in pathogen-rich ecologies could invest more effort in resisting pathogens [e.g., through greater production of pathogen-combating cytokines (41)] rather than avoiding them. Of course, our parasite stress data, like most used in this literature (36), were measured at the country level, and we cannot rule out the possibility that individual disgust sensitivity is calibrated by individual rather than national pathogen exposure. However, findings here corroborate previous results indicating that childhood illness in a pathogen-rich location (Bangladesh) is unrelated to disgust sensitivity in adulthood (42).

The observed null relationship between disgust sensitivity and national parasite stress suggests that different processes might account for the relationships between ideology and national parasite stress versus ideology and disgust sensitivity. At the national level, those norms categorized as “traditional” might be more successfully transmitted and sustained within pathogen-rich ecologies if such norms lead to reduced contact with pathogens (9–11, 20). Indeed, mathematical models indicate that pathogens can result in the cultural evolution of prophylactic rules and rituals (43). Alternatively, traditionalism might promote within-coalition alliances that can provide health care in times of illness, which might be especially critical in high parasite stress ecologies (14, 19, 44, 45). Alternatively, traditional norms might endure more in pathogen-rich nations simply because the ecologies of such nations are less hospitable to liberal Western institutions and infrastructures, and were thus less influenced by European colonialism (46).

At the individual level, those who are more motivated to avoid pathogens might especially find traditional rules and rituals appealing for a number of reasons. Relative to less restricted sex (i.e., more experimental, more partners), sexual practices often categorized as traditional expose individuals to fewer pathogens (39) and reduce the ability for sexually transmitted infections to thrive within communities (47). Traditional food preparation techniques often include ingredients with antimicrobial properties (10), traditional food taboos sometimes limit pathogen and toxin exposure (7, 48), and traditional hygiene rules can coordinate behaviors to limit pathogen transmission (e.g., when one hand is used to contact bodily waste and is not used for physical contact with foods or with social allies). Within each of these accounts, relationships between pathogen avoidance and traditionalism could solely reflect motivations to avoid direct contact with pathogens, or they could also reflect motivations to regulate others’ behavior, which might indirectly increase infection risk (18, 47). Just as we have attempted to clarify why the behavioral immune system might relate to political ideology, based on either norm adherence or outgroup avoidance, future work can clarify which of these aspects of traditionalism might be especially appealing to those individuals especially motivated to avoid pathogens.

Methods

The study was reviewed and approved by the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Vaste Commissie Wetenschap en Ethiek Institutional Review Board. Further ethical approval was obtained where required by local ethics boards. Consent was gathered after participants read an information sheet describing the contents of the survey.

Participants.

We recruited participants in 30 countries (Table 1). We aimed to enroll at least 200 participants in each country and to recruit participants from both universities and the general population. After excluding participants who (i) reported being less than 18 y old, (ii) did not report their sex, or (iii) had completely missing data for any of the instruments described below, our final sample consisted of 11,501 participants [42% male, with a mean age of 30.06 y (SD = 12.62)].

Measures.

Participants completed a short questionnaire described as concerning “attitudes toward political issues and groups of people.” In all but one country (Sweden, where English fluency is high), questionnaires were translated into the official or native language, with multiple languages offered in some multilingual countries (language details are provided in Table 1). The questionnaire contained measures of traditionalism, SDO, and disgust sensitivity. It also included items peripherally related to this study, including sex, age, religious attendance, endorsement of policy issues (e.g., should society increase its use of nuclear power?), and attitudes toward different types of people. We focus only on traditionalism, SDO, and disgust sensitivity here, but the English version of the survey (including all items) is available in SI Appendix.

Traditionalism.

We assessed traditionalism using the six-item short form of the traditionalism facet of the authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism scale (25). This instrument relates strongly to religiosity and other manifestations of traditional values. Example items include “the ‘old-fashioned ways’ and ‘old-fashioned values’ still show the best way to live” and “this country will flourish if young people stop experimenting with drugs, alcohol, and sex, and pay more attention to family values.” Responses were recorded on a 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) scale.

SDO.

The four-item short SDO scale (49) was used to assess SDO. The instrument has been used in at least one previous multinational study, where it consistently (negatively) related to desires to protect ethnic and religious minorities across cultures (49). Example items include “in setting priorities, we must consider all groups” (reverse coded) and “we should not push for group equality.” Responses were recorded on a 0 (extremely oppose) to 6 (extremely favor) scale.

Disgust Sensitivity.

Most research in the behavioral immune system literature has operationalized pathogen-avoidance motives using self-report measures of disgust sensitivity or contamination sensitivity (36). We used the seven-item pathogen factor of the three-domain disgust scale (50) for the current investigation, for two reasons: (i) Its item content appears more interpretable to individuals from diverse cultures relative to other instruments, and (ii) it is less confounded with sexual openness and neuroticism than other disgust sensitivity instruments (39, 51). Participants reported how disgusting they find each of six items on a 0 (not at all disgusting) to 6 (extremely disgusting) scale. Example items include “stepping on dog poop” and “sitting next to someone who has red sores on their arm.”

Parasite Stress.

Researchers have used several different indices to estimate parasite stress (36), with the most frequently used being the historical prevalence of pathogens within regions (52) and the contemporary frequency of nonzoonotic parasites within regions (14). These two estimates were strongly correlated for the 30 nations sampled here (r = 0.75). We opted to use the historical prevalence estimates because they were less strongly skewed, with nation-level results less strongly influenced by the higher parasite stress nations sampled here (e.g., India, Brazil). No conclusions changed when using the nonzoonotic disease estimates, or when we used alternative parasite stress estimates (zoonotic parasites and contemporary infectious disease deaths; details and results are provided in SI Appendix). To facilitate visual interpretation of results (Figs. 1–3), we added a constant to each nation’s parasite stress score so that the lowest scoring country (Canada) had a value of zero.

Analytical Strategy.

Data were analyzed in SPSS version 23 using random slope, random intercept, linear mixed modeling with restricted maximum likelihood estimation criteria. Participants (level 1 units) were nested within nations (level 2 units). Given that our samples varied in their sex ratio and mean age, we controlled for participant sex and age. We used disgust sensitivity as a level 1 predictor to test for effects of individual pathogen-avoidance motivations on SDO and traditionalism. We used historical parasite prevalence as a level 2 variable to test for effects of parasite stress on SDO, traditionalism, and pathogen-avoidance motivations. We allowed the effects of each level 1 variable to vary across level 2. Our analyses can thus be described as follows, where Yij refers to traditionalism or SDO for individuals (i) within nations (j):

We also tested whether disgust sensitivity (Yij below) varied across nations as a function of parasite stress, with the following model:

After multilevel analyses, we meta-analyzed the level 1 effects using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software. This strategy allows for a point estimate of the effect size of the relationship between disgust sensitivity and the two dimensions of ideology, as well as 95% CIs for those relationships. Each country was treated as a different sample. For both traditionalism and SDO, we conducted two meta-analyses of the relationship with disgust sensitivity. The first involved meta-analyzing the observed effect size within each country, and the second involved meta-analyzing the effect size after disattenuating for the country-specific unreliability in disgust sensitivity, traditionalism, and SDO.

Alternative Parasite Stress Estimates

The main text reports analyses using estimates of national historical parasite prevalence to operationalize parasite stress. The supplementary analyses reported here describe results when alternative variables are used to operationalize parasite stress. We report results using historical parasite prevalence [i.e., analyses used in the main text (52)] and two alternative estimates. The first alternative uses nonzoonotic infectious disease estimates (14), and the second alternative uses the first component extracted from a principal component analysis on historical parasite stress, nonzoonotic infections disease, zoonotic infectious disease estimates, and 2012 WHO infectious disease deaths per country. This principal component was log-transformed to correct for positive skew. Correlations between the historical prevalence estimate reported in the main text and the nonzoonotic disease estimate and the principal component were r = 0.54 and r = 0.85, respectively, and the correlation between the nonzoonotic disease estimate and the principal component was r = 0.86. All nation-level results reported below control for level 1 effects of participant sex, participant age, and disgust sensitivity.

Traditionalism.

The effect of national parasite stress on traditionalism was similar across operationalizations of parasite stress: historical pathogen prevalence [t(26.54) = 4.16, P < 0.001], nonzoonotic infectious disease estimate [t(27.32) = 3.23, P < 0.01], and the principal component from multiple estimates [t(27.13) = 3.36, P < 0.01]. Correlations between national traditionalism averages and the three parasite stress indices were r = 0.70, r = 0.51, and r = 0.62, respectively.

SDO.

The effect of national parasite stress on SDO was similar across operationalizations of parasite stress: historical pathogen prevalence [t(25.19) = 0.11, P = 0.91], nonzoonotic infectious disease estimate [t(24.86) = 0.91, P = 0.37], and the principal component from multiple estimates [t(24.97) = 0.57, P = 0.57]. Correlations between national SDO averages and the three parasite stress indices were r = −0.06, r = −0.17, and r = −0.17, respectively.

Cross-National Variability in Disgust Sensitivity.

The effect of national parasite stress on disgust sensitivity was similar across operationalizations of parasite stress: historical pathogen prevalence [t(26.18) = 1.12, P = 0.28], nonzoonotic infectious disease estimate [t(25.69) = 0.12, P = 0.91], and the principal component from multiple estimates, [t(26.21) = 0.93, P = 0.36]. Correlations between national disgust sensitivity averages and the three parasite stress indices were r = 0.18, r = 0.14, and r = 0.11, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.M.T., publication costs, and open access funds are supported by the European Research Council [(ERC) StG-2015 680002-HBIS].

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1607398113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Curtis VA. Dirt, disgust and disease: A natural history of hygiene. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(8):660–664. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.062380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart BL. Behavioral adaptations to pathogens and parasites: Five strategies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1990;14(3):273–294. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaller M, Park JH. The behavioral immune system (and why it matters) Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2011;20:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tybur JM, Lieberman D, Kurzban R, DeScioli P. Disgust: Evolved function and structure. Psychol Rev. 2013;120(1):65–84. doi: 10.1037/a0030778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeBruine LM, Jones BC, Tybur JM, Lieberman D, Griskevicius V. Women’s preferences for masculinity in male faces are predicted by pathogen disgust, but not moral or sexual disgust. Evol Hum Behav. 2010;31:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JH, van Leeuwen F, Stephen ID. Homeliness is in the disgust sensitivity of the beholder: Relatively unattractive faces appear especially unattractive to individuals higher in pathogen disgust. Evol Hum Behav. 2012;33:569–577. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fessler DMT, Navarrete CD. Meat is good to taboo: Dietary proscriptions as a product of the interaction of psychological mechanisms and social processes. J Cogn Cult. 2003;3:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller SL, Maner JK. Overperceiving disease cues: The basic cognition of the behavioral immune system. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;102(6):1198–1213. doi: 10.1037/a0027198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray DR, Schaller M. The behavioral immune system: Implications for social cognition, social interaction, and social influence. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2016;53:75–129. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billing J, Sherman PW. Antimicrobial functions of spices: Why some like it hot. Q Rev Biol. 1998;73(1):3–49. doi: 10.1086/420058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaller M, Murray DR. Pathogens, personality, and culture: Disease prevalence predicts worldwide variability in sociosexuality, extraversion, and openness to experience. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(1):212–221. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terrizzi JA, Shook NJ, McDaniel MA. The behavioral immune system and social conservatism: A meta-analysis. Evol Hum Behav. 2013;34:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fincher CL, Thornhill R, Murray DR, Schaller M. Pathogen prevalence predicts human cross-cultural variability in individualism/collectivism. Proc Biol Sci. 2008;275(1640):1279–1285. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fincher CL, Thornhill R. Parasite-stress promotes in-group assortative sociality: The cases of strong family ties and heightened religiosity. Behav Brain Sci. 2012;35(2):61–79. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X11000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornhill R, Fincher CL. The Parasite-Stress Theory of Values and Sociality: Infectious Disease, History and Human Values Worldwide. Springer; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornhill R, Fincher CL, Aran D. Parasites, democratization, and the liberalization of values across contemporary countries. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2009;84(1):113–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray DR, Schaller M, Suedfeld P. Pathogens and politics: Further evidence that parasite prevalence predicts authoritarianism. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faulkner J, Schaller M, Park JH, Duncan LA. Evolved disease-avoidance mechanisms and contemporary xenophobic attitudes. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2004;7:333–353. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navarrete CD, Fessler DM. Disease avoidance and ethnocentrism: The effects of disease vulnerability and disgust sensitivity on intergroup attitudes. Evol Hum Behav. 2006;27:270–282. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray DR, Schaller M. Threat(s) and conformity deconstructed: Perceived threat of infectious disease and its implications for conformist attitudes and behavior. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2012;42:180–188. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Leeuwen F, Park JH, Koenig BL, Graham J. Regional variation in pathogen prevalence predicts endorsement of group-focused moral concerns. Evol Hum Behav. 2012;33:429–437. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jost JT, Federico CM, Napier JL. Political ideology: Its structure, functions, and elective affinities. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:307–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duckitt J, Sibley CG. A dual process motivational model of ideology, politics, and prejudice. Psychol Inq. 2009;20:98–109. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zakrisson I. Construction of a short version of the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale. Pers Individ Dif. 2005;39:863–872. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duckitt J, Bizumic B, Krauss SW, Heled E. A tripartite approach to right‐wing authoritarianism: The authoritarianism‐conservatism‐traditionalism model. Polit Psychol. 2010;31:685–715. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pratto F, Sidanius J, Stallworth LM, Malle BF. Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:741–763. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altemeyer B. The other “authoritarian personality”. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1998;30:47–92. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duckitt J. A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2001;33:41–114. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roccato M, Ricolfi L. On the correlation between right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2005;27:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duriez B, Van Hiel A. The march of modern fascism: A comparison of social dominance orientation and authoritarianism. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;32:1199–1213. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sibley CG, Robertson A, Wilson MS. Social dominance orientation and right‐wing authoritarianism: Additive and interactive effects. Polit Psychol. 2006;27:755–768. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duckitt J, Sibley CG. Right wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice. Eur J Pers. 2007;21:113–130. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitley BE., Jr Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and prejudice. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77:126–134. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomsen L, Green EG, Sidanius J. We will hunt them down: How social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism fuel ethnic persecution of immigrants in fundamentally different ways. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2008;44:1455–1464. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollet TV, Tybur JM, Frankenhuis WE, Rickard IJ. What can cross-cultural correlations teach us about human nature? Hum Nat. 2014;25(3):410–429. doi: 10.1007/s12110-014-9206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tybur JM, Frankenhuis WE, Pollet TV. Behavioral immune system methods: Surveying the present to shape the future. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences. 2014;8:274–283. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oaten M, Stevenson RJ, Case TI. Disgust as a disease-avoidance mechanism. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(2):303–321. doi: 10.1037/a0014823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tybur JM, Bryan AD, Lieberman D, Hooper AEC, Merriman LA. Sex differences and sex similarities in disgust sensitivity. Pers Individ Dif. 2011;51:343–348. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tybur JM, Inbar Y, Güler E, Molho C. Is the relationship between pathogen avoidance and ideological conservatism explained by sexual strategies? Evol Hum Behav. 2015;36:489–497. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tybur JM, Lieberman D. Human pathogen avoidance adaptations. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016;7:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaller M, Miller GE, Gervais WM, Yager S, Chen E. Mere visual perception of other people’s disease symptoms facilitates a more aggressive immune response. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(5):649–652. doi: 10.1177/0956797610368064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Barra M, Islam MS, Curtis V. Disgust sensitivity is not associated with health in a rural Bangladeshi sample. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka MM, Kumm J, Feldman MW. Coevolution of pathogens and cultural practices: A new look at behavioral heterogeneity in epidemics. Theor Popul Biol. 2002;62(2):111–119. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.2002.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugiyama LS. Illness, injury, and disability among Shiwiar forager-horticulturalists: Implications of health-risk buffering for the evolution of human life history. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2004;123(4):371–389. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Navarrete CD, Fessler DMT. Normative bias and adaptive challenges: A relational approach to coalitional psychology and a critique of terror management theory. Evol Psychol. 2005;3:297–325. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hruschka DJ, Henrich J. Institutions, parasites and the persistence of in-group preferences. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauch CT, McElreath R. Disease dynamics and costly punishment can foster socially imposed monogamy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11219. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henrich J, Henrich N. The evolution of cultural adaptations: Fijian food taboos protect against dangerous marine toxins. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277(1701):3715–3724. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pratto F, et al. Social dominance in context and in individuals: Contextual moderation of robust effects of social dominance orientation in 15 languages and 20 countries. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2013;4:587–599. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tybur JM, Lieberman D, Griskevicius V. Microbes, mating, and morality: Individual differences in three functional domains of disgust. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):103–122. doi: 10.1037/a0015474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inbar Y, Pizarro DA, Iyer R, Haidt J. Disgust sensitivity, political conservatism, and voting. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2012;3:537–544. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murray DR, Schaller M. Historical prevalence of infectious disease within 230 geopolitical regions: A tool for investigating origins of culture. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2010;41:99–108. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.