Since it was first found capable of suppressing transformation by E1A and RAS oncogenes (1), and then shortly thereafter discovered to be mutationally inactivated in over half of all human tumors (2), uncovering how the TP53 tumor suppressor (hereafter p53) inhibits tumor initiation and progression has remained one of the holy grails of the cancer field. At no point in this journey has p53 been readily forthcoming about its secret tumor-suppressor activities, and there have been many twists and turns along the way. In PNAS, Ou et al. (3) take us one step toward what recent data indicate might be the correct pathway of tumor suppression, with their identification of SAT1 (spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1), a mediator of polyamine catabolism, and ALOX15 (arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase), a lipid oxygenase, in a recently identified activity of p53 in the regulation of ferroptosis.

Ferroptosis is an iron-mediated, caspase-independent, pathway of cell death that requires the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxides. This pathway was first discovered by Stockwell and colleagues in 2012 (4), and this group later showed that this pathway was controlled by GPX4, a glutathione-regulated lipid repair enzyme (5). In 2015, Gu and colleagues implicated ferroptosis as a critical component of tumor suppression by p53 (6). However, before describing the collision between the fields of p53 and ferroptosis, it would be informative to analyze the data of Ou et al. (3) in a historical context, by highlighting the 27-year search for the key activities of p53 in tumor suppression. Throughout this quest, scientists focused on two questions: first, what stimulus does p53 “sense” when it becomes activated to suppress tumor development? And second, what key target genes does p53 regulate to eliminate the precancerous cell?

The Search for the Key Activities of p53 in Tumor Suppression

Some of the first-described p53 target genes that were found to align in a common pathway were called “PIGs,” for p53-induced genes. These gene products appeared to play a concerted role at inducing oxidative damage in the cell (7). For the most part however, the importance of this pathway to tumor suppression was not fully appreciated, and focus was placed on the ability of p53 to induce programmed cell death, or apoptosis, by virtue of its ability to regulate pro- and antiapoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) family proteins in the cell (see, for example, ref. 8). The importance of this pathway to p53-mediated tumor suppression was supported by data from many researchers, but perhaps best supported by the findings that dominant-negative caspases or overexpression of BCL2 could “substitute” for mutation of p53 in tumor development, as least in some cellular contexts (9). The fascination with the premise that p53-mediated apoptosis was paramount for tumor suppression persisted, until the Lozano group created a mouse model for a mutant of p53 that was defective at this activity, but capable of inducing senescence and suppressing tumor development (10). This finding highlighted the premise that p53 could use both its apoptosis and senescence pathways to suppress tumor development, and the conclusion was made that this choice was likely to be context or cell-type specific.

With regard to “upstream” signals, it was found that p53 protein could sense the extent of genotoxic stress in the cell, signaled by phosphorylation of p53 by DNA damage-activated kinases like ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) (11). Alternatively, the presence of activated oncogenes in the cell was signaled to p53 by its positive regulator p14ARF (12). Activated p53 could transactivate the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN1A to induce growth arrest and allow DNA repair, or senescence if the repair was deemed irreparable (13). In other cell types where BCL2 family members were limiting, the transactivation of BH3-only (BCL2-homology 3) genes, like PUMA by p53, tipped the scale toward cell death (14). Therefore, years of research produced models for p53-mediated tumor suppression that were intuitive, robust, and logical.

Ferroptosis, a New Pathway for p53-Mediated Tumor Suppression

Our concepts of p53-mediated tumor suppression started to unravel when the Attardi group created a synthetic mutant of p53 that was incapable of transactivating the majority of known p53 target genes, but was capable of suppressing cancer, both in unstressed organisms and in some cancer-prone mouse models (15, 16). To punctuate this unraveling, in 2012 the Gu group reported that a mutant form of p53 that fails to be acetylated on certain residues of the DNA binding domain was incapable of inducing growth arrest or apoptosis, but was capable of suppressing spontaneous tumor development in an unstressed organism (17). Gu and colleagues subsequently reported that, whereas this mutant of p53 was markedly defective for growth arrest, senescence, and apoptosis, it was capable of sensitizing cells to ferroptosis (6). Gu and colleagues showed that p53 regulated ferroptosis in part by negative regulation of SLC7A11, a component of the cystine/glutamate antiporter, system xc−. The ability of p53 to transcriptionally repress SLC7A11 was shown to lead to decreased cystine import, which would lead to reduced glutathione production and increased ROS, an important component of ferroptosis (6). However, at this point how p53 might contribute to the other important component of ferroptosis, lipid peroxides, was not clear.

The potential relevance of p53 to ferroptosis, and ferroptosis to p53-mediated tumor suppression, was supported by research from two other groups. First, Jiang and colleagues performed an elegant biochemical study identifying glutaminolysis as critical for ferroptosis (18). Their research implicated GLS2, a p53-regulated glutaminase, as essential for ferroptosis. Then the Murphy group identified a polymorphic variant of p53 that at first blush appeared to be the Yin-Yang complement to the Attardi and Gu mice: this variant of p53 was capable of inducing growth arrest and apoptosis, but incapable of suppressing tumor development. Transcriptionally, this variant showed impaired ability to repress SLC7A11 or transactivate GLS2. Indeed, both human and murine cells containing this variant were markedly defective at inducing ferroptosis, and silencing of GLS2 essentially phenocopied this defect in cells with wild-type p53 (19). At this point, the search was on for an elucidation of the pathway whereby p53 regulates ferroptosis.

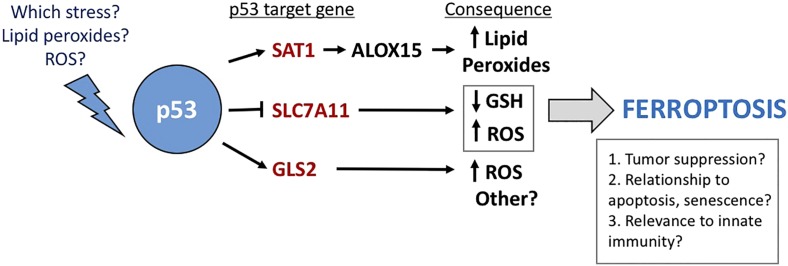

The Ou et al. (3) study in PNAS sheds light on how p53 regulates ferroptosis by highlighting the relationship of a novel p53 target gene, SAT1, to lipid peroxide accumulation, which is essential for ferroptosis. The authors show that SAT1 is a direct p53 target gene, and that increased SAT1 cooperates with ROS to lead to increased lipid peroxides and ferroptotic cell death. Notably, Ou et al. show that SAT1 levels are reduced in a large percentage of human tumor samples, and that knockout of SAT1 markedly reduces p53-mediated ferroptosis. Mechanistically, Ou et al. show that increased SAT1 leads to increased levels of ALOX15, an iron-binding enzyme that oxidizes polyunsaturated fatty acids. Furthermore, the authors show that a small-molecule inhibitor of ALOX15 was effective at inhibiting ferroptosis induced by SAT1 and ROS. Thus, the puzzle as to one mechanism whereby p53 may regulate lipid peroxides was solved, and the pathway of p53-mediated ferroptosis begins to emerge (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The pathway whereby p53 mediates ferroptosis. Shown are the p53 target genes involved, their consequence in the cell, and some questions that remain.

Remaining Questions

The study by Ou et al. (3) raises several important questions regarding ferroptosis and p53. There are likely other p53 target genes that contribute to ferroptosis, and these need to be identified. Additionally, according to data from Ou et al., neither p53 nor SAT1 alone appear to be capable of inducing ferroptosis; rather, these genes appear to regulate the threshold of sensitivity to ferroptosis inducers. So what else is needed? One interesting fact discovered by Ou et al. is that tetracycline-inducible SAT1 had no impact on cell viability in cultured cells, yet was capable of causing tumor regression in vivo. Given the

The Ou et al. study in PNAS sheds light on how p53 regulates ferroptosis by highlighting the relationship of a novel p53 target gene, SAT1, to lipid peroxide accumulation, which is essential for ferroptosis.

role of ALOX15 in inflammation and immunity (20), and the fact that the nude mice used in the study by Ou et al. (3) have an intact innate immune system, it is tempting to speculate on the involvement of the innate immune system in ferroptotic cell death and tumor suppression by p53. What about the PIG genes, which increase oxidative stress in the cell? Are these unknown players in the ferroptotic pathway? Furthermore, what is the “stress” that p53 responds to when it sensitizes to ferroptosis? Is it lipid peroxides that might accumulate after oncogenic or metabolic stress (21)? A key emerging question is whether ferroptosis inducers can be effectively used in the treatment of tumors that have inactivated the p53 pathway. Finally, how do we reconcile the abundant data that the growth arrest and apoptotic pathways also contribute to p53-mediated tumor suppression? One intriguing possibility is that these three pathways communicate with one another, and abrogating any one—or two—may reveal the tumor-suppressor potential of the remaining pathway.

One final thought. A key piece of information that should shed light on the relevance of ferroptosis to tumor suppression by p53 regards the evolutionary-conservation of the p53-ferroptosis pathway, which is not known. It has been suggested that Planaria is the simplest vertebrate organism that uses p53 to suppress tumor development (22), but in Planaria p53 seems to function predominantly to limit stem cell biology and self-renewal. Are these activities related to ferroptosis? Are there ties with the pathways of iron homeostasis, ROS, metabolism, and ferroptosis, all of which p53 regulates, to stem cell biology, cell fate, and self-renewal? A better understanding of the evolution of p53-mediated ferroptosis should give us key insight into the function of p53. But more importantly, the hope is that a firmer understanding of how p53 mediates tumor suppression will lead to the design and testing of new anticancer strategies to combat cancer, both in those tumors with mutations in p53 and those tumors that retain wild-type p53. These and other questions will continue to fuel the quest for the search for the key activities of p53 in tumor suppression.

Acknowledgments

The author’s research is supported by NIH Grants CA102184 and CA201430.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page E6806.

References

- 1.Finlay CA, Hinds PW, Levine AJ. The p53 proto-oncogene can act as a suppressor of transformation. Cell. 1989;57(7):1083–1093. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC. p53 mutations in human cancers. Science. 1991;253(5015):49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ou Y, Wang S-J, Li D, Chu B, Gu W. Activation of SAT1 engages polyamine metabolism with p53-mediated ferroptotic responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E6806–E6812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607152113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon SJ, et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang WS, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156(1-2):317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang L, et al. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520(7545):57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature14344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polyak K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. A model for p53-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1997;389(6648):300–305. doi: 10.1038/38525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vousden KH. Apoptosis. p53 and PUMA: A deadly duo. Science. 2005;309(5741):1685–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.1118232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitt CA, et al. Dissecting p53 tumor suppressor functions in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2002;1(3):289–298. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu G, et al. Chromosome stability, in the absence of apoptosis, is critical for suppression of tumorigenesis in Trp53 mutant mice. Nat Genet. 2004;36(1):63–68. doi: 10.1038/ng1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banin S, et al. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science. 1998;281(5383):1674–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough WG. ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways. Cell. 1998;92(6):725–734. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.el-Deiry WS, et al. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75(4):817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano K, Vousden KH. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;7(3):683–694. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brady CA, et al. Distinct p53 transcriptional programs dictate acute DNA-damage responses and tumor suppression. Cell. 2011;145(4):571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang D, et al. Full p53 transcriptional activation potential is dispensable for tumor suppression in diverse lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(41):17123–17128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111245108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li T, et al. Tumor suppression in the absence of p53-mediated cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence. Cell. 2012;149(6):1269–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao M, Monian P, Quadri N, Ramasamy R, Jiang X. Glutaminolysis and transferrin regulate ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2015;59(2):298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennis M, et al. An African-specific polymorphism in the TP53 gene impairs p53 tumor suppressor function in a mouse model. Genes Dev. 2016;30(8):918–930. doi: 10.1101/gad.275891.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uderhardt S, Krönke G. 12/15-lipoxygenase during the regulation of inflammation, immunity, and self-tolerance. J Mol Med (Berl) 2012;90(11):1247–1256. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0954-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shibata T, et al. Identification of a lipid peroxidation product as a potential trigger of the p53 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(2):1196–1204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearson BJ, Sánchez Alvarado A. A planarian p53 homolog regulates proliferation and self-renewal in adult stem cell lineages. Development. 2010;137(2):213–221. doi: 10.1242/dev.044297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]