Abstract

Background

Anxiety and depression are common psychological comorbidities that impact the quality of life (QoL) of patients. In this systematic review, we 1) determined the impact of anxiety and depression on outcomes in patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and 2) summarized unique challenges these comorbidities present to current OA management.

Patients and methods

A systematic literature search was performed using the OVID Medline and EMBASE databases until April 2016. Full-text research articles published in English from the year 2000 onward with a sample size of >100 were included in this review. Eligible research articles were reviewed and the following data were extracted: study author(s), year of publication, study design, and key findings.

Results

A total of 38 studies were included in the present review. The present study found that both anxiety and/or depression were highly prevalent among patients with OA. Patients with OA diagnosed with these comorbidities experienced more pain, had frequent hospital visits, took more medication, and reported less optimal outcomes. Management strategies in the form of self-care, telephone support, audio/video education programs, and new pharmacotherapies were reported with favorable results.

Conclusion

Anxiety and depression adversely impact the QoL of patients with OA. Physicians/caregivers are highly recommended to consider these comorbidities in patients with OA. Ultimately, a holistic individualized management approach is necessary to improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, anxiety, depression, impact, management

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common musculoskeletal disease worldwide.1 It is characterized by degeneration of the articular cartilage, osteophyte formation, and asymmetric joint space narrowing.2 These changes often lead to significant pain and disability and create a substantial individual, societal, and economic burden.3,4 Since the incidence and prevalence of OA increase with age, longer life expectancy will only increase these measures in the future.5 Current management largely emphasizes on alleviating symptoms and improving function, but for many these interventions do not provide adequate symptom relief. This variability in symptoms and outcomes among individuals with OA cannot be explained by the disease pathology alone.

Several factors are being investigated to explain differences in patient-reported symptoms and outcomes, of which anxiety and depression have begun to emerge as strong candidates.6,7 Anxiety is defined as the presence of “fear or nervousness about what might happen”.8 When this fear produces behavioral and physiological changes, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-V) denotes this as anxiety disorder.9 Depression, on the other hand, is defined as the presence of sad, empty, or irritable mood. Both anxiety and depression are accompanied by somatic and cognitive changes that can significantly affect an individual’s capacity to function.9 Outside of OA, studies have consistently reported that anxiety and depression have significant impacts on cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory disorders, and gastrointestinal conditions.10–12 Patients suffering from chronic painful disabling conditions frequently report anxiety and depression as comorbidities.13 This may predispose patients to experience pain more often, as recent evidence suggests that anxiety and depression can alter pain threshold levels.14 Since chronic pain in itself can cause or aggravate anxiety and depression,15 a vicious cycle begins, which can significantly impact the course and management of these chronic diseases.

Several studies have evaluated the concordance between OA, anxiety, and depression. Although substantial work has been conducted to elucidate the role of anxiety and depression in patients with OA, this study seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding regarding the impact these comorbidities have on OA symptoms, patient outcomes, and challenges they prensent towards disease management.

Patients and methods

Eligibility criteria

Original studies of 1) human subjects that 2) assessed anxiety or depression during any time point of the 3) OA disease course 4) regarding its impact on patient-reported symptoms and outcomes along with 5) different interventions employed to manage these comorbidities were included for this review. We limited eligibility to studies that were only in English language. Review articles, letters to the editor, published abstracts, book series, short surveys, notes, editorials, and case series were excluded. It has been reported that even with statistically significant results, studies with low sample sizes are less likely to reflect a true effect;16,17 therefore, reports concerning <100 patients were excluded. Additionally, only articles with full-text versions published from the year 2000 onward were eligible for this review to focus on recent updates in OA, anxiety, and depression.

Search strategy and criteria

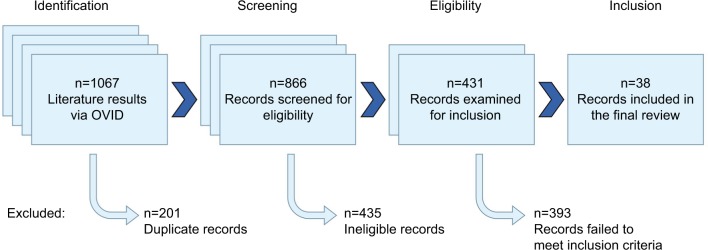

A manual electronic search of the OVID Medline (from 1996) and EMBASE (from 1974) databases was performed in duplicate by two authors (AS and PK) to identify studies published until April 2016 that assessed the impact or management of anxiety or depression in patients with OA. The following search string was used: “(osteoarthritis) and (anxiety or depression) and (impact or management)”. One thousand and sixty-seven records were identified after excluding non-English results. After performing automated deduplication using the OVID search interface, 866 studies remained.

Study selection

Citation records were extracted to Excel spreadsheet software (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) and sorted by publication-type metadata. No specialized systematic review software packages were used. Publication types not meeting inclusion criteria were removed (Figure 1). These records were manually screened for eligibility by two authors (AS and PK), and any doubt regarding inclusion/exclusion of a particular study was addressed by discussion between the two authors. Unresolved conflicts were managed by discussion with two additional authors (QS and RG). Four hundred and thirty-five records were excluded as 233 were review articles, 174 were published abstracts, seven were conference papers, seven were notes, six were editorials, three were short surveys, two were letters, two were meta-analysis, and one was a book series. After excluding further 356 records based on title and abstract information, 21 records with a sample size of <100, and 16 records based on year of publication, 38 records were included in the final review.18–55 No systematic search of article bibliographies or conference proceedings was performed in an attempt to identify any additional unpublished or otherwise unidentified data. Full-length articles of the remaining 38 records were obtained and included in our final synthesis (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram summarizing the literature search, screening, and review.

Table 1.

Final studies with authors, year of publication, design, and key findings

| Authors | Year | Design | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axford et al55 | 2008 | n=170 patients completed trial of PEP to determine what may hinder its efficacy in knee OA. | Greater pain was associated with reduced coping, increased depression, and reduced physical ability. |

| Ayral et al54 | 2002 | Prospective randomized study of n=112 (56/group) to access impact of video information on pre-operative anxiety of patients scheduled to undergo joint lavage for knee OA. | Pre-operative anxiety was lowered by half for patients who had viewed the video. Tolerability of knee lavage was also significantly better in the video group. |

| Blagestad et al53 | 2016 | Cross-sectional study of n=39,688 participants undergoing THA from 2005 to 2011 to investigate redeemed medications. | Surgery reduced prescriptions of analgesics, hypnotics, and anxiolytics, but not anti-depressants. |

| Buszewicz et al52 | 2006 | Randomized controlled trial, n=812 patients aged >50 hip and/or knee OA and pain and/or disability randomized to six sessions of self-management and education booklet (intervention group) or education booklet alone (control group). | The two groups showed significant differences at 12 months on the anxiety sub-score of HADS. No significant difference was seen in number of visits to the GP at 12 months. |

| Collantes-Esteve and Fernandez-Perez 51 | 2003 | Open-label multi-center study with n=2,228 investigated the effect of a switch from celecoxib to rofecoxib among patients with OA. | The switch to rofecoxib from celecoxib favorably influenced proportions of patients with self-reported depression. |

| Croft et al50 | 2005 | Mailed patient survey of n=8,995 individuals aged >50 years. Patients completed the SF-36, HADS, and WOMAC. | Severity of knee pain and related disability are worse in the presence of pain elsewhere. |

| Dailiana et al49 | 2015 | Investigate and compare the impact of primary THA (n=174) and TKA (n=204) on QoL, patients’ satisfaction and detect the effect of patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics on outcome. WOMAC and CES-D10 pre- and post-operative. | WOMAC and CES-D10 improved significantly 1 year post-operatively. |

| Dieppe et al48 | 2000 | Prospective study, n=500 patients, study of natural history of peripheral joint OA and its impact over 8 years. Patients reviewed at 3 and 8 years. HAQ and HADS. | The mean HAQ and HADS scores at 8 years were high, especially in those with knee disease, indicating significant disability as a result of the disease. |

| Ellis et al47 | 2012 | Effect of psychopathology on the rate of improvement following TKA (n=154). | Subjects in the psychopathology group showed significantly lower SF-36 mental component summary scores both at baseline and 1 year post-operatively. |

| Gerrits et al46 | 2014 | Prospective analysis of impact of chronic diseases and pain characteristics in n=1,122 individuals with remitted depressive or anxiety disorder. | Pain, not chronic disease, increases the likelihood of depression recurrence, largely through its association with aggravated sub-threshold depressive symptoms. |

| Gignac et al45 | 2013 | Middle- and older-age adults with OA, n=177 or no chronic disabling conditions, n=193, aged >40 years completed a telephone interview and self-administered questionnaire assessing demographics, SRPQ, and psychological variables. | Middle-aged adults with OA reported significantly greater role limitations and more health care utilization than all other groups. Middle-aged adults and those with OA also reported greater depression, stress, role conflict, and behavioral coping efforts than older adults or healthy controls. |

| Hanusch et al44 | 2014 | n=100, influence of psychological factors, including perception of illness, anxiety, and depression, on recovery and functional outcome after TKA. Function was assessed pre-operative, 6 weeks, and 1 year after using OKS and ROM. | Pre-operative function had the biggest impact on post-operative outcome for ROM and OKS. Depression and anxiety associated with a higher (worse) knee score at 1 year. |

| Hawker et al43 | 2011 | Community cohort, n=529 participants with hip/knee OA. Telephone interviews assessed OA pain and disability using three time points over 2 years. | Current OA pain strongly predicted future fatigue and disability; fatigue and disability in turn predicted future depressed mood; depressed mood and fatigue were interrelated such that depressed mood exacerbated fatigue and vice versa, and that fatigue and disability, but not depressed mood, led to worsening of OA pain. |

| Kingsbury and Conaghan42 | 2012 | Random online survey on assessment and treatment of OA, n=1,006 GPs randomly selected and invited to participate in, on factors influencing their management, burden on their practice, and on the need for improving care. | Achieving adequate pain control and lack of time were the most frequently cited challenges, whereas more time with patients, collaboration with specialist colleagues, and improved communication tools were the most common needs identified to improve OA management. |

| Kirkness et al41 | 2012 | Pre- and post-operative measures of pain, physical function using LEFS, and QoL of n=168 patients were evaluated. | Most common comorbidities in these patients were osteoarthritis, hypertension, and major depressive disorders. |

| Lin et al40 | 2003 | Randomized controlled trial, n=1,801, depressed older adults with coexisting arthritis, performed at 18 primary care clinics to evaluate whether care for depression changes pain and outcome. | Benefits of improved depression care extended beyond reduced depressive symptoms and included decreased pain as well as improved functional status and QoL. |

| Lin et al39 | 2006 | Multi-site randomized-controlled trial n=1,001 participants with depression and arthritis. Baseline and 12-month interviews assessed arthritis pain severity and activity interference, depression, analgesic use, and overall functional impairment. | Systematic depression management was more effective than usual care in decreasing pain severity among arthritis patients with lower initial pain severity. |

| Liu et al38 | 2016 | Patients with primary hand OA, n=247, consulting secondary care, underwent physical examination for the number of joints with bony joint enlargements, soft tissue swelling and deformities, and radiographs. | Hand OA patients report esthetic dissatisfaction with their hands regularly. This dissatisfaction has a negative impact in a small group of patients who also reported more depression and negative illness perceptions. |

| Lopez-Olivo et al37 | 2011 | Evaluation of n=241 patients undergoing TKA, before and 6 months after surgery. Multiple regression models evaluated associations of baseline demographic and psychosocial variables. | Perioperative psychosocial evaluation and intervention are crucial in enhancing TKA outcomes. |

| Marks36 | 2007 | Cross-sectional analyses, n=100, unilateral and bilateral radiographic and symptomatic knee OA patients underwent standard assessment using several validated questionnaires and a series of walking tests on level ground. | Efforts to heighten self-efficacy for pain and other symptoms management may influence the affective status, function, and effort-related perceptions of people with knee OA quite significantly. |

| Marks35 | 2009 | n=1,000 hip OA surgical candidates examined for any historical/concurrent evidence of depression/anxiety. | Those with depression and anxiety histories were more impaired before surgery and tended to recover more slowly than those with no such history. |

| Montin et al34 | 2007 | Longitudinal follow-up study, n=100 participants, State Trait Anxiety Inventory was used to measure patients’ level of anxiety before surgery and at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months post-operatively. | Patients’ pre-operative trait anxiety impaired HRQoL both before and after surgery. |

| Nour et al33 | 2006 | Older adult women (n=102) and men (n=11) with OA or RA were randomly assigned to experimental (n=68) or wait list control (n=45) groups. CES-D at baseline, pre-intervention, and post-intervention. | Self-management intervention can successfully improve involvement in exercise and relaxation among housebound older adults with arthritis. |

| Ozcakir et al32 | 2011 | n=100 knee OA patients; investigate relationship between radiological severity and clinical/psychological factors. KL, WOMAC, 15 m walk, 10-step climb. | Depression was significantly higher in late-stage knee OA group. Radiological severity is an important indicative factor for pain, disability, depression, and social isolation. |

| Perruccio et al31 | 2012 | Prospective study of n=494 participants who completed patient-reported outcome pre- and 12 months post-TKA. WOMAC, POMS, and HADS scoring methods used. | As symptomatic joint count increase, so does anxiety and depression both pre- and post-operatively. A comprehensive approach to OA management/care is warranted. |

| Pinto et al30 | 2013 | n=124 patients assessed 24 hours before (T1) and 48 hours after (T2) surgery. Demographic, clinical, and psychological factors were assessed at T1 and several post-surgical pain issues, anxiety, and analgesic consumption were evaluated at T2. | Positive correlation between post-surgical anxiety and acute pain was reported. |

| Rosemann et al29 | 2007 | Survey of n=1,021 participants to assess the prevalence, severity, and predictors of depression in a large sample of patients with OA. | There is high prevalence of depression among patients with OA and perceived pain and few social contacts were strongest predictors. |

| Rosemann et al28 | 2007 | Patient questionnaires, n=1,021 to assess the impact of concomitant depression on QoL and health service utilization of patients with OA. | Appropriate treatment of depression would appear not only to increase QoL but also to lower costs by decreasing health service utilization. |

| Rosemann et al27 | 2007 | Cross-sectional survey, n=1,250 OA patients to assess factors associated with visits to GPs, orthopedists, and non-physician practitioners. | Psychological factors contribute to the increased use of health care providers. |

| Rosemann et al26 | 2007 | Determined factors associated with functional disability in n=1,021 patients with OA via questionnaires. | Main factors associated with functional disability were depression, pain, and few social contacts. |

| Rosemann et al25 | 2008 | Cross-sectional survey of n=1,021 OA patients to determine factors associated with pain intensity in primary care. | Severity of depression showed the strongest association with pain intensity. |

| Sale et al24 | 2008 | Prospective cohort study, n=1,227 individuals ≥62 years with hip/knee OA completed CES-D, WOMAC, and other questionnaire. | Prevalence of depressive symptoms was high in adults with OA. Higher depressed mood was independently and significantly associated with female gender, greater pain and fatigue, stressful life events, more coping behaviors, and receiving treatment for depression/mental illness. |

| Stamm et al23 | 2014 | Health interview survey including n=3,097 subjects aged >65 years with OA, back pain, or osteoporosis to explore health care utilization compared to controls. | Patients with OA, back pain, or osteoporosis visited GPs and were hospitalized more often than controls. Problems in the ADLs, pain intensity, and anxiety/depression influenced GP consultations. |

| Steigerwald et al22 | 2012 | Open-label, Phase 3b study of n=195 patients to evaluate the effectiveness and tolerability of tapentadol for severe, chronic OA knee pain. | Tapentadol significantly improved pain intensity, HRQoL, and function in patients with inadequately managed, severe, chronic OA knee pain. |

| Theiler et al21 | 2002 | 3-week prospective open-label multi-center study with rofecoxib 25 mg daily in n=134 (mean 69 years, SD=8) outpatients with painful OA flares of the knee or the hip. | Rofecoxib significantly SF-12 and WOMAC scores, in OA patients. |

| Wylde et al20 | 2012 | Patients listed for a primary TKA were recruited from pre-operative assessment clinics. Pre-surgical evaluation included WOMAC, PSES, HAD, and SACQ questionnaires and questions about other painful joints. Patients then completed the WOMAC Pain and Function Scales at one year post-operatively. | Significant predictors of post-operative pain were greater anxiety and higher pain severity. Other significant predictors of post-operative disability were greater anxiety, worse functional disability, and a greater number of painful joints elsewhere. |

| Yilmaz et al19 | 2015 | Patients with RA (n=142), FMS (n=136), knee OA (n=139) and healthy women controls (n=152) were analyzed using VAS, BDI, FIQ, TPC, DAS-28, HAQ, and WOMAC. | Positive correlation was determined between BDI, VAS, and WOMAC scores in the knee OA group. However, level of depression was only related to disease severity in women with FMS. |

| Zullig et al18 | 2015 | Data were from patients (n=300) enrolled in a randomized control trial examined the association of comorbidities with baseline-OA PROs: pain, physical function, depressive symptoms, fatigue, and insomnia. | Depression was associated with worse pain, fatigue, and insomnia. Evidence that comorbidity burden is associated with worse OA-related PROs. |

Abbreviations: AIMS, Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale; ASMP, Arthritis Self-Management Program; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D, Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; DAS-28, Disease Activity Score-28; FIQ, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; FMS, fibromyalgia syndrome; GPs, general practitioners; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAQ, Health assessment questionnaire; HSCL-20, Hopkins Symptom Checklist Depression Scale; IPQ-R, Illness Perceptions Questionnaire-Revised; KL, Kellgren–Lawrence grading; KSS, Knee Society Scale; LEFS, Lower Extremity Function; OA, osteoarthritis; OKS, Oxford Knee Score; PEP, Patient Education Program; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; POMS, Profile of Mood States; PSES, Pain Self-Efficacy Scale; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; ROM, Goniometer-measured range of movement; SACQ, Self-Administered Co-morbidity Questionnaire; SF-36, SF-12, Short Form Health Survey; SRPQ, Social Role Participation Questionnaire; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; TPC, tender point counts; WOMAC, Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; PROs, Patient-reported Outcomes; ADLs, Activities of Daily Living.

Data collection

Data extraction included the following elements: 1) authors, year of publication, 2) study design, and 3) key findings.

Study designs and study quality

Of all the final studies included in this review, six were randomized controlled trials,18,33,39,40,52,54 14 were prospec tive cohort studies,20,21,30,31,34,37,41,44,46,48,49,51,55,56 14 were cross-sectional studies,19,25–29,32,36,38,43,45,47,53,57 one was a retro spective analysis,35 and three were surveys.23,42,50

Results

Sample and setting

Of the original 866 English articles, 38 articles fulfilled our aforementioned criteria and thus were included for analysis in this review.18–55 These 38 articles outline the impact of anxiety and/or depression on patients living with OA and the challenges these comorbidities present in OA management, wherein some studies also examined approaches on how to address these challenges. The age of patients analyzed in most of these studies was consistent with the age at which OA and depression are commonly diagnosed. However, one study specified a younger cutoff age range in their inclusion criteria.45 Gignac et al45 reported that middle-aged patients with OA (mean age 50.8 years) reported more depression compared to elderly subjects (mean age 67.8 years) having similar OA severity. This difference was attributed to role limitation and dissatisfaction among middle-aged OA individuals. Most studies included both male and female participants. However, in one study, sex was an eligibility criterion, as this study focused solely on female participants.19 Studies were carried out in different settings viz university hospital, general practitioner (GP) clinics, and via telephone/mailed surveys. All studies published after year 2000 were analyzed (Table 1).

Anxiety and depression

All studies evaluated anxiety and/or depression either as a primary or a secondary objective. Various scoring methods were utilized, of which Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)58 and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) were most popular.59 Both CES-D and HADS have been extensively used and studied, and are considered reliable and valid research tools.60 Other scoring methods used were Composite International Diagnostic Interview,13 36-Item or the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12, SF-36),61 Hopkins Symptom Checklist Depression Scale,62 Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System,63 Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ),64 visual analog scale, Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale,65 Beck Depression Inventory,66 and the Health Education Impact Questionnaire.67 Apart from these scores, clinical diagnosis based on patient interviews was also utilized.

OA pathology and disease severity

Most studies focused on lower extremity OA (hip and knee), with one study examining hand OA38 patients. Diagnosis was based on clinical presentation or radiographs. Patients from the entire spectrum of disease severity were studied. The Kellgren and Lawrence (KL) radiographic grading system was most often used to report OA severity; however, some studies did not use any specific grading method. One study included patients with early (KL I, II) and late (KL III, IV) stage OA.32 Pain was a consistent feature across most studies and was assessed primarily using the Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.68 In addition to OA, two studies also assessed patients with rheumatoid arthritis.19,33

Epidemiology of anxiety and depression in patients with OA

Three studies reported on the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with OA.24,29,41 Rosemann et al29 conducted a cross-sectional survey in 1,021 patients with OA and reported that psychological factors (viz anxiety and depression) were highly prevalent among the patients (19.76% of male and 19.16% of female participants reported a PHQ-9 score of ≥15). Similar results were reported by Sale et al24 in a cross-sectional study where 21.3% of 1,227 participants reported a CES-D score of ≥16. Likewise, Kirkness et al41 reported that major depressive disorder was commonly prevalent in patients scheduled for total knee arthroplasty.

Impact

Impact of anxiety and depression on OA symptoms

Of the 38 studies included in our final analysis, 13 studies examined the impact of anxiety and depression on OA symptoms.18,19,26,31,32,38,43,45,46,48,50,55 There was a considerable overlap in reporting impact of these psychological conditions on patients with OA with pain being the key central element. Studies reported that the prevalence of anxiety and depression was interrelated to index joint pain,55 pain at multiple sites,31,50 pain intensity,25 and OA severity.32 Pain was in turn associated with depression and its recurrence.46 Hawker et al43 also reported that current OA pain predicted future fatigue, disability, and depressed mood. In addition to its impact on OA pain, concurrent depression was also interrelated to significant participation restriction and physical limitation.26,45

Impact of anxiety and depression on OA outcomes

Nine studies examined the impact of anxiety and depression on the outcomes of patients with OA.20,27,30,34,35,37,44,52,53 Studies reported that anxiety and depression increased GP visits,52 health care utilization,27 drug prescriptions,53 adversely affected surgical outcomes,30,34,35,37,44 and increased post-surgical pain.20

Impact of anxiety and depression on patients with OA: sex differences

Our results indicate that anxiety and depression differentially impact lives of male and female patients with OA. Sale et al24 reported that higher level of depressed mood was independently and significantly associated with the female sex.

Management challenges

Thirteen studies evaluated management challenges in patients with OA with comorbid anxiety and depression.21–23,28,33,36,39,40,42,47,49,51,54 The present study found that anxiety and depression posed unique challenges to physicians in 1) diagnosis, 2) structuring a proper management plan, and 3) effective pharmacotherapy.

Challenges in diagnosis of anxiety and depression

Primary care physicians or GPs infrequently considered or found it difficult to diagnose anxiety and/or depression in patients with OA.28,42

Challenges in self-care, collaborative care, social/phone support

Management regimes advocating self-care, social/phone support, and educational engagements in patients with OA with comorbid anxiety and depression were reported. Lin et al39 reported that systematic depression management (antidepressant pharmacotherapy and/or problem-solving treatment) was more effective than usual care in decreasing pain severity among patients with arthritis with lower initial pain severity, but not among patients with higher initial pain severity. On the contrary, Buszewicz et al52 reported that although self-management reduced anxiety, it had no significant effect on pain, physical functioning, or number of GP visits at 12 months.

Challenges in pharmacotherapy

Pharmacological challenges exist in managing patients with OA with comorbid anxiety and depression. These challenges juxtaposed with the demographics of this patient cohort (advanced age and presence of other medical comorbidities) make pharmacotherapy difficult. Therefore, it is vital to investigate new treatment modalities that could effectively manage these conditions with minimum adverse effects. The present study found that rofecoxib and tapentadol were reported to improve pain and depressive symptoms of patients with OA. Theiler et al21 assessed the effects of rofecoxib on quality of life (QoL) in elderly patients with painful OA flares who were not responsive to or had adverse reactions to previous NSAID therapy. The authors reported that rofecoxib significantly improved QoL, as measured by the SF-12. Similarly, Collantes-Esteve and Fernandez-Perez51 found rofecoxib to favorably influence patients with OA with self-reported depression. In addition to rofecoxib, use of tapentadol (prolonged and immediate release) has also been reported in patients with chronic painful knee OA. Steigerwald et al22 evaluated effectiveness of tapentadol prolonged release in 195 patients with chronic OA knee pain and found significant improvement in pain intensity, QoL, SF-36, and HADS.

New management approaches: music, video, and yoga

In recent years, various new and innovative management methodologies have been investigated. Ayral et al54 reported that advocating video education information on the planned procedure before surgery lowered perioperative anxiety. Music therapy and yoga have also been reported to help improve patient anxiety and depression; however, the sample sizes of their respective studies were small.69,70

Discussion

Psychological comorbidities (anxiety and depression) are highly prevalent among patients with OA.24,29,41,49 These comorbidities are frequently associated with higher pain and physical limitation,18,19,26,31,32,38,43,45,46,48,50,55 poor outcomes to both conservative and surgical interventions,20,30,31,34,35,37,44,47,56 and increased pharmacotherapy and health care utilization.23,48 Our results indicate that standardized interventions to manage these comorbidities are lacking as a number of different self-care management programs, telephone support programs, video information support programs, and new drug treatments were reported in the literature with varied success.21–23,28,33,36,39,40,42,47,49,51,54 This variability in patient care highlights the complex relationship that exists between OA, anxiety, and depression (Table 2). Yet, these comorbidities are commonly overlooked by many primary care physicians and GPs who either solely focus on physical aspects of OA or simply fail to assess patients’ psychological state altogether.71 It is imperative to recognize these comorbidities, as these can influence disease course and management, ultimately affecting functional outcomes.

Table 2.

Summary of results

| Impact | Summary | |

|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | Psychological factors such as anxiety and depression are commonly prevalent in patients with OA. | |

| OA symptoms | Anxiety and depression contribute to index joint pain and its intensity. This pain can predict future fatigue, disability, and depressed mood. | |

| OA outcomes | Anxiety and depression increase GP visits, health care and drug utilization, post-surgical pain, and adverse outcomes. | |

| Sex differences | Anxiety and depression differentially impact lives of male and female patients with OA, with females showing higher levels of depressed mood. | |

|

| ||

| Management challenges | Summary | Suggestions |

|

| ||

| Challenges in diagnosis | Physicians found it difficult to diagnose anxiety and/or depression in patients with OA. | Adopt NICE guidelines toward holistic assessment of patients with OA. |

| Challenges in self-care, collaborative care, social/phone support | Anxiety and depression pose as a challenge to physicians in structuring a management plan. Studies have reported use of various management programs with variable success. | Use “à la carte” approach. Thorough timely patient assessment required following initiation of program to access for improvement. |

| Challenges in pharmacotherapy | Rofecoxib and tapentadol were reported to have favorable results. | Cocktail pharmacotherapy. Other drugs like duloxetine have been approved by FDA for use in this patient cohort. |

| New management approaches | Music, video, and yoga have been tried with favorable results. | Can be employed as adjuvants. |

Abbreviations: FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; GP, general practitioner; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; OA, osteoarthritis.

Anxiety and depression are interrelated with pain and physical limitation, the two key OA symptoms. Studies in our review have revealed that anxiety and depression can significantly impair QoL of patients by altering pain perception and functional capacity.24 Therefore, educating physicians about timely identification of psychosocial factors such as anxiety and depression that may pre-date OA pathology or result as a consequence of the disease can improve the QoL of patients living with these comorbidities. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has outlined recommendations regarding holistic assessment of patients with OA (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177), which serves as an excellent starting point and it is highly recommended that physicians consult this document. Thus, implementation of appropriate screening questionnaires can help identify these psychological comorbidities at an earlier stage, which could in effect provide adequate lead time to implement a management plan that could improve outcomes and lower future health care burden and costs.

OA is a progressive disease and a large portion of patients with OA will, at some point, undergo surgery. Patients awaiting surgery can experience anxiety; however, educating them about the procedure and advocating a self-care plan can change health-directed behaviors. While surgery does improve QoL of patients, patients with OA with comorbid anxiety and depression may not experience similar favorable clinical outcomes following joint replacement surgery as seen in patients with OA without these comorbidities,20,30,34,35,37,44,47,56 even after a structured rehabilitation program.72 Thus, surgical indications in patients with OA with comorbid anxiety and depression should be critically assessed as not all patients report similar benefits following surgery.

As seen in our results, OA management strategies include self-care, collaborative care, social/phone support, pharmacotherapy, music, educational videos about OA procedures, and yoga. Self-care, collaborative care, and social/phone support should be integrated into OA management, as these strategies have been shown to alter comorbid anxiety and depression, as well as resulting physical and emotional pain. Similarly, pharmacotherapy should also be appropriately integrated into OA management; however, this should be done carefully, as the treatment of OA, depression, anxiety, and pain through pharmacotherapy carries the danger of drug interactions and adverse side effects. From our study, we can suggest rofecoxib and tapentadol to improve QoL and pain of patient with OA and encourage the development of new treatment modalities that work in tandem to treat OA symptoms, as well as comorbidities. Additionally, there is evidence that anti-depressant medications such as duloxetine can improve pain in patients with OA,73 suggesting a central mechanism that may connect OA pain and depression. Therefore, it would be appropriate to consider implementing anti-depressant/anti-anxiety therapy in tandem with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or analgesic drugs to address these different pain pathways concurrently. This multi-faceted pharmacological approach can greatly benefit patients in this cohort. Other newer modalities such as music, videos, and yoga are management methods that have recently gained more attention, as they have been shown to improve patient outcomes. Music has been shown to reduce levels of anxiety, depression, and pain. Likewise, videos educating patients on their planned surgical procedures have lowered pre-operative anxiety. These modalities can act as adjuvants to current management strategies.

To create individualized OA management strategies, it is essential to recognize that patients with early OA disease experience less anxiety and depression compared to patients with late-stage disease.32 Therefore, radiological severity of OA can serve as an indicative factor for intensity of depression in patients with OA. This concept should be further investigated. Similarly, sex differences are prevalent independently in OA, anxiety, and depression.74,75 Studies have reported that female patients with OA report greater anxiety and depression24,76 and lower QoL38 than males. Moreover, female patients with OA may have different expectations than their male counterparts and therefore may require a completely different management approach.

It is important to state that present literature fails to fully address the management strategies in dealing with psychological comorbidities seen in patients with OA. It is rather clear that one treatment does not fit all, as seen in the present review. On one end self-management interventions did not improve pain, QoL, or depression,77 while on the other hand, self-management did produce improvement in exercise and relaxation activities in depressed patients although not as much as in patients without depression.33 These conflicting results highlight the challenges present in the management of these comorbidities today. It should also be highlighted that recruiting and retaining patients in management programs is also challenging and should be further evaluated to increase patient compliance, as depressed patients tend to lack interest from the outset. Furthermore, another factor in need of consideration is age, and how reports of depression/anxiety can differ based on patients’ age group. To garner an accurate understanding of how depression/anxiety interacts with OA, it is important to consider the possibility that different age groups experience varying degrees of depression/anxiety, based on a diverse set of factors, such as socioeconomic status and health complications. Recent trends in depression suggest its high prevalence among individuals aged 40–59 years, which may thus affect the presentation of OA to a greater degree in middle-aged cohorts than younger or elderly cohorts.78 Therefore, examining the impact and management challenges of anxiety and depression in an age-stratified OA cohort should be further investigated.

Although our results provide a comprehensive summary of the current state of literature, a considerable lack of studies originating from outside of North America and Europe is noted. This could be attributed to the fact that outpatient visits and in-patient admissions for mental health diseases are higher in the US and Europe,79 or it could simply underscore a general lack of research initiatives in the developing world, or that psychological conditions largely remain under-recognized and/or under-diagnosed. Thus, the inclusion of studies from developing nations may provide a more detailed picture of the relationship between anxiety, depression, and OA. We also acknowledge that the exclusion of reports not published in English may have introduced institutional bias. Furthermore, in addition to the inherent weaknesses of the studies reviewed, our study may be skewed by publication bias, as there is a well-described prejudice toward the publication of positive findings. Nevertheless, we believe that the present review accurately presents the current state of evidence concerning the impact and management challenges of anxiety and depression encountered by patients with OA.

Conclusion

In summary, the majority of evidence regarding impact of anxiety and depression in patients with OA suggests reduced QoL and poor clinical outcomes. The current literature fails to lay a blueprint to tackle the management challenges seen. OA stage-specific stratification may help guide management. However, further studies are needed to formulate definitive management strategies to deal with OA-associated anxiety and depression and should focus on high-quality randomized controlled trials with patients stratified into non-operative, pre-operative/operative, and post-operative groups.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Jason Rockel, Research Associate at Krembil Research Institute, for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work

References

- 1.Johnson VL, Hunter DJ. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lories RJ, Luyten FP. The bone-cartilage unit in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(1):43–49. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter DJ, Schofield D, Callander E. The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(7):437–441. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Litwic A, Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull. 2013;105:185–199. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. National Arthritis Data Workgroup Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Axford J, Butt A, Heron C, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in osteoarthritis: use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(11):1277–1283. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1547-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Baar ME, Dekker J, Lemmens JA, Oostendorp RA, Bijlsma JW. Pain and disability in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: the relationship with articular, kinesiological, and psychological characteristics. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(1):125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Merriam-Webster.com [homepage on the Internet] Anxiety. 2016. [Accessed September 16, 2016]. Available from: http://www.merriam-webster.com/

- 9.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maurer J, Rebbapragada V, Borson S, et al. ACCP Workshop Panel on Anxiety and Depression in COPD Anxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needs. Chest. 2008;134(4 suppl):43S–56S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Januzzi JL, Jr, Stern TA, Pasternak RC, DeSanctis RW. The influence of anxiety and depression on outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(13):1913–1921. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Andrews JM, Holtmann GJ. Controversies surrounding the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a literature review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(2):225–234. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He Y, Zhang M, Lin EH, et al. Mental disorders among persons with arthritis: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med. 2008;38(11):1639–1650. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neogi T, Nevitt MC, Yang M, Curtis JR, Torner J, Felson DT. Consistency of knee pain: correlates and association with function. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(10):1250–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen GR, Streltzer J. The psychology of pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23(2):339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Button KS, Ioannidis JP, Mokrysz C, et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(5):365–376. doi: 10.1038/nrn3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuesch E, Trelle S, Reichenbach S, et al. Small study effects in meta-analyses of osteoarthritis trials: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2010;341:c3515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zullig LL, Bosworth HB, Jeffreys AS, et al. The association of comorbid conditions with patient-reported outcomes in Veterans with hip and knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(8):1435–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2707-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yılmaz H, Karaca G, Demir Polat HA, Akkurt HE. Comparison between depression levels of women with knee osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia syndrome: a controlled study. Turk J Phys Med Rehab. 2015;61:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wylde V, Dixon S, Blom AW. The role of preoperative self-efficacy in predicting outcome after total knee replacement. Musculoskeletal Care. 2012;10(2):110–118. doi: 10.1002/msc.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theiler R, Bischoff HA, Good M, Uebelhart D. Rofecoxib improves quality of life in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2002;132(39–40):566–573. doi: 10.4414/smw.2002.10075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steigerwald I, Muller M, Kujawa J, Balblanc JC, Calvo-Alen J. Effectiveness and safety of tapentadol prolonged release with tapentadol immediate release on-demand for the management of severe, chronic osteoarthritis-related knee pain: results of an open-label, phase 3b study. J Pain Res. 2012;5:121–138. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S30540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stamm TA, Pieber K, Blasche G, Dorner TE. Health care utilisation in subjects with osteoarthritis, chronic back pain and osteoporosis aged 65 years and more: mediating effects of limitations in activities of daily living, pain intensity and mental diseases. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2014;164(7–8):160–166. doi: 10.1007/s10354-014-0262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sale JE, Gignac M, Hawker G. The relationship between disease symptoms, life events, coping and treatment, and depression among older adults with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(2):335–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosemann T, Laux G, Szecsenyi J, Wensing M, Grol R. Pain and osteoarthritis in primary care: factors associated with pain perception in a sample of 1,021 patients. Pain Med. 2008;9(7):903–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosemann T, Laux G, Kuehlein T. Osteoarthritis and functional disability: results of a cross sectional study among primary care patients in Germany. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosemann T, Joos S, Szecsenyi J, Laux G, Wensing M. Health service utilization patterns of primary care patients with osteoarthritis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:169. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosemann T, Gensichen J, Sauer N, Laux G, Szecsenyi J. The impact of concomitant depression on quality of life and health service utilisation in patients with osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2007;27(9):859–863. doi: 10.1007/s00296-007-0309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosemann T, Backenstrass M, Joest K, Rosemann A, Szecsenyi J, Laux G. Predictors of depression in a sample of 1,021 primary care patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(3):415–422. doi: 10.1002/art.22624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinto PR, McIntyre T, Ferrero R, Almeida A, Araujo-Soares V. Predictors of acute postsurgical pain and anxiety following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Pain. 2013;14(5):502–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perruccio AV, Power JD, Evans HM, et al. Multiple joint involvement in total knee replacement for osteoarthritis: effects on patient-reported outcomes. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(6):838–846. doi: 10.1002/acr.21629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozcakir S, Raif SL, Sivrioglu K, Kucukcakir N. Relationship between radiological severity and clinical and psychological factors in knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(12):1521–1526. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1768-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nour K, Laforest S, Gauvin L, Gignac M. Behavior change following a self-management intervention for housebound older adults with arthritis: an experimental study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montin L, Leino-Kilpi H, Katajisto J, Lepisto J, Kettunen J, Suominen T. Anxiety and health-related quality of life of patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. Chronic Illn. 2007;3(3):219–227. doi: 10.1177/1742395307084405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marks R. Comorbid depression and anxiety impact hip osteoarthritis disability. Disabil Health J. 2009;2(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marks R. Physical and psychological correlates of disability among a cohort of individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Can J Aging. 2007;26(4):367–377. doi: 10.3138/cja.26.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez-Olivo MA, Landon GC, Siff SJ, et al. Psychosocial determinants of outcomes in knee replacement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(10):1775–1781. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.146423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu R, Damman W, Beaart-van de Voorde L, et al. Aesthetic dissatisfaction in patients with hand osteoarthritis and its impact on daily life. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016;45(3):219–223. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2015.1079731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin EH, Tang L, Katon W, Hegel MT, Sullivan MD, Unutzer J. Arthritis pain and disability: response to collaborative depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(6):482–486. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. IMPACT Investigators Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(18):2428–2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirkness CS, McAdam-Marx C, Unni S, et al. Characterization of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty in a real-world setting and pain-related medication prescriptions for management of postoperative pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2012;26(4):326–333. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2012.734898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kingsbury SR, Conaghan PG. Current osteoarthritis treatment, prescribing influences and barriers to implementation in primary care. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2012;13(4):373–381. doi: 10.1017/S1463423612000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hawker GA, Gignac MA, Badley E, et al. A longitudinal study to explain the pain-depression link in older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(10):1382–1390. doi: 10.1002/acr.20298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanusch BC, O’Connor DB, Ions P, Scott A, Gregg PJ. Effects of psychological distress and perceptions of illness on recovery from total knee replacement. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):210–216. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B2.31136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gignac MA, Backman CL, Davis AM, Lacaille D, Cao X, Badley EM. Social role participation and the life course in healthy adults and individuals with osteoarthritis: are we overlooking the impact on the middle-aged? Soc Sci Med. 2013;81:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerrits MM, van Oppen P, Leone SS, van Marwijk HW, van der Horst HE, Penninx BW. Pain, not chronic disease, is associated with the recurrence of depressive and anxiety disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellis HB, Howard KJ, Khaleel MA, Bucholz R. Effect of psychopathology on patient-perceived outcomes of total knee arthroplasty within an indigent population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(12):e84. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dieppe P, Cushnaghan J, Tucker M, Browning S, Shepstone L. The Bristol ‘OA500 study’: progression and impact of the disease after 8 years. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8(2):63–68. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dailiana ZH, Papakostidou I, Varitimidis S, et al. Patient-reported quality of life after primary major joint arthroplasty: a prospective comparison of hip and knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:366. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0814-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Croft P, Jordan K, Jinks C. “Pain elsewhere” and the impact of knee pain in older people. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(8):2350–2354. doi: 10.1002/art.21218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collantes-Estevez E, Fernandez-Perez C. Improved control of osteoarthritis pain and self-reported health status in non-responders to celecoxib switched to rofecoxib: results of PAVIA, an open-label post-marketing survey in Spain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19(5):402–410. doi: 10.1185/030079903125001938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buszewicz M, Rait G, Griffin M, et al. Self management of arthritis in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;333(7574):879. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38965.375718.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blagestad T, Nordhus IH, Gronli J, et al. Prescription trajectories and effect of total hip arthroplasty on the use of analgesics, hypnotics, antidepressants, and anxiolytics: results from a population of total hip arthroplasty patients. Pain. 2016;157(3):643–651. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ayral X, Gicquere C, Duhalde A, Boucheny D, Dougados M. Effects of video information on preoperative anxiety level and tolerability of joint lavage in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47(4):380–382. doi: 10.1002/art.10559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Axford J, Heron C, Ross F, Victor CR. Management of knee osteoarthritis in primary care: pain and depression are the major obstacles. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(5):461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Riddle DL, Kong X, Fitzgerald GK. Psychological health impact on 2-year changes in pain and function in persons with knee pain: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(9):1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim KW, Han JW, Cho HJ, et al. Association between comorbid depression and osteoarthritis symptom severity in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(6):556–563. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL). A measure of primary symptom dimensions. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1974;7(0):79–110. doi: 10.1159/000395070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. PROMIS Cooperative Group The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meenan RF, Gertman PM, Mason JH. Measuring health status in arthritis. The arthritis impact measurement scales. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(2):146–152. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Osborne RH, Elsworth GR, Whitfield K. The Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ): an outcomes and evaluation measure for patient education and self-management interventions for people with chronic conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(2):192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bellamy N. The WOMAC knee and hip osteoarthritis indices: development, validation, globalization and influence on the development of the AUSCAN Hand Osteoarthritis Indices. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 suppl 39):S148–S153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Middleton KR, Ward MM, Haaz S, et al. A pilot study of yoga as self-care for arthritis in minority communities. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:55. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ottaviani S, Bernard JL, Bardin T, Richette P. Effect of music on anxiety and pain during joint lavage for knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(3):531–534. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Turner J, Kelly B. Emotional dimensions of chronic disease. West J Med. 2000;172(2):124–128. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.von der Hoeh NH, Voelker A, Gulow J, Uhle U, Przkora R, Heyde CE. Impact of a multidisciplinary pain program for the management of chronic low back pain in patients undergoing spine surgery and primary total hip replacement: a retrospective cohort study. Patient Saf Surg. 2014;8:34. doi: 10.1186/s13037-014-0034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abou-Raya S, Abou-Raya A, Helmii M. Duloxetine for the management of pain in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2012;41(5):646–652. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.O’Connor MI. Sex differences in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(suppl 1):S22–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Theis KA, Helmick CG, Hootman JM. Arthritis burden and impact are greater among U.S. women than men: intervention opportunities. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16(4):441–453. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Crotty M, Prendergast J, Battersby MW, et al. Self-management and peer support among people with arthritis on a hospital joint replacement waiting list: a randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(11):1428–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2009–2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 79.WHO . Mental Health Atlas 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar]