Abstract

Background

The aim of the study was to assess the accuracy of ultrasound shear wave elastography in the diagnosis of adenomyosis.

Methods

One hundred and fifty three patients were examined. Ninety-seven patients were with suspected adenomyosis and 56 patients were with unremarkable myometrium. Adenomyosis was confirmed in 39 cases (A subgroup) and excluded in 14 cases (B subgroup) in the main group based on morphological examination. All patients underwent ultrasound examination using an Aixplorer (Supersonic Imagine, France) scanner with application of shear wave elastography during transvaginal scanning. Retrospective analysis of the elastography criteria against the findings from morphological/histological examination was performed.

Results

The following values of Young’s modulus were found in subgroup A (adenomyosis): Emean – 72.7 (22.6–274.2) kPa (median, 5–95th percentiles), Emax – 94.8 (29.3–300.0) kPa, SD – 9.9 (2.6–26.3) kPa; in subgroup B (non adenomyosis) – 28.3 (12.7–59.5) kPa, 33.6 (16.0–80.8) kPa, 3.0 (1.4–15.6) kPa; in the control group – 24.4 (17.9–32.4) kPa, 29.8 (21.6–40.8) kPa, 2.3 (1.3–6.1) kPa, respectively (P < 0.05 for all comparison with subgroup В and the control group). The Emean cut-off value for adenomyosis diagnosis was 34.6 kPa. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and area under curve (AUC) were 89.7%, 92.9%, 97.2%, 76.5% and 0.908. The Emax cut-off value was 45.4 kPa (89.7%, 92.9%, 97.2%, 76.5% and 0.907, respectively).

Conclusion

This study showed a significant increase of the myometrial stiffness estimated with shear wave elastography use in patients with adenomyosis.

Keywords: Ultrasound shear wave elastography, stiffness, Young’s modulus, adenomyosis

Introduction

Adenomyosis is one of the most extensive pathologies of the upper female reproductive system, secondary to leiomyoma and inflammatory diseases. According to different authors, the prevalence of adenomyosis varies from 10–15% up to 60–70% depending on the population examined and diagnostic methods used.1,2 In all, 20 to 48% of women with infertility suffer from genital endometriosis and adenomyosis particularly. Prevalence of adenomyosis among women with chronic pelvic pain syndrome is 70%.3 It is essential to note the oncological potential of this pathology, as there are several reported cases of malignant transformation of adenomyosis to endometrial adenocarcinoma.4–7 The disease recurrence after palliative removal of an abnormal focus reaches 30–50%, and adenomyosis can therefore be compared with a tumour process.8,9

Adenomyosis can be a subtle, infiltrative disease and accurate diagnosis can, therefore, be challenging. Advanced cases may be resistant to conservative treatment and can involve nearby organs, considerably complicating surgical treatment.2 Early detection of the disease is therefore important for clinical practice. Uterine enlargement, menstrual disorders such as dysmenorrhoea, menorrhagia, dysfunctional uterine bleeding and pelvic pain are considered to be the typical clinical hallmarks of adenomyosis. However, these symptoms coincide with histologic diagnosis in as few as 22–65% of cases.10,11

Preoperative diagnostic tools are required to avoid unnecessary hysterectomy based on inaccurate clinical diagnosis and to investigate non-surgical and minimally invasive surgical alternatives. The basis for relevant implementation of diagnostic imaging tools is understanding of the relationship between image findings and the characteristic structural pathological changes and the diagnostic accuracy of these findings.12 The following examination methods are most commonly used for the diagnosis of adenomyosis in clinical practice: hysteroscopy,13 ultrasound12 and magnetic resonance imaging.14,15

Studies reporting the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound for adenomyosis are rather contradictory; its accuracy is in the range of 38.4 to 86.4%.16–20 According to Levgur,21 who analyzed publications in the English-language literature for 56 years (from 1949 to 2005), the sensitivity of ultrasound in the diagnosis of adenomyosis is between 50 and 87%. According to Dueholm,12 the sensitivity of transvaginal ultrasound varied between 53 and 89% and the specificity between 50 and 99%.

The subjective nature of B-mode image interpretation by each operator is a recognized limitation of ultrasound as a modality and is undoubtedly the cause of the accuracy range mentioned above. The image characteristics of adenomyosis most commonly seen during the transvaginal examination include heterogeneous and hypoechogenic, poorly circumscribed areas in the myometrium.19 These areas may appear with or without anechoic lacunae or cysts of varying size, and the echo texture of the myometrium may be increased. Moreover, there may be linear striations radiating out from the endometrium into the myometrium, and an indistinct endomyometrial junction with a pseudo-widening of the endometrium.22

Nowadays, many authors report high accuracy levels of magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis of adenomyosis by evaluation of the junctional zone.14,15 Unfortunately, high cost of examination limits the use of this method for routine examination. That is why, in spite of the significant success of magnetic resonance imaging for gynaecological pathology diagnostics, especially adenomyosis, ultrasound remains the primary noninvasive method of diagnosis.19

Many new developments in ultrasound techniques have provided additional information from the ultrasound examination with little extra effort from the practitioner. The most important have been contrast-enhanced ultrasound and ultrasound elastography. These combined with B-mode, colour and spectral Doppler, 3D and 4D imaging create multiparametric ultrasound.23 Two main forms of ultrasound elastography have become established in clinical practice. These are strain elastography and shear wave elastography.24–26 All current commercial elastography systems need to measure tissue displacement. The various systems differ in how the displacement is used; it may be imaged directly and converted to strain (strain elastography), or used to detect the time of arrival of shear-waves and hence their speed (shear wave elastography). The shear-wave speed can be converted to a Young’s modulus value, and the measurement given in kPa.27

Shear wave elastography is becoming an increasingly popular technique in the diagnosis of different organs and systems diseases.24 It is known that characteristic changes of the myometrial structure in cases of adenomyosis include the growth of adenomyosis foci within the interfascial compartment of connective tissue between the fascicles of hypertrophic smooth muscle cells, accompanied by myometrial hyperaemia, lymphostasis, oedema of perivascular myometrium tissue and leiomyomatosis of myometrial perifocal hyperplasia around adenomyosis foci.28,29 These changes in the tissue ultrastructure may modify the stiffness of the myometrium, which can be detected by ultrasound elastography.

The aim of this retrospective study was to assess the value of ultrasound shear wave elastography in the diagnosis of adenomyosis and to compare the obtained data with the results of morphological examination of operative material.

Materials and methods

One hundred fifty-three patients were examined. All patients underwent examination and treatment at the Diagnostic Centre and Department of Surgical Gynecology of S.P. Botkin City Clinical Hospital, Moscow. Ethical Committee approval was given, and written consents were obtained prior to commencing the study. Ninety-seven patients among 153 patients were with suspected adenomyosis (including standard ultrasound criteria (Figure 1)).12,30 Their average age was 48 years old (30–70, 28–75) (median, 5–95th percentiles, minimum–maximum values). Fifty-three patients among those 97 patients underwent hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy. The main indications for hysterectomy were regular and irregular pathological menorrhagia with iron deficient anaemia of patients due to adenomyosis with uterine fibroids and adnexal pathology. Forty-five patients among those 97 patients underwent hysteroscopy only. Indications for hysteroscopy were as follows: menorrhagia and dysfunctional uterine bleeding suspicious for adenomyosis, endometrial pathology (endometrial polyp and glandular hyperplasia) and submucous leiomyoma and investigation of the uterus in cases of infertility. Although hysteroscopy is one of the methods which can be used for diagnosis of adenomyosis by visualization of hypervascularization, strawberry pattern, cystic localized lesions or endometrial defects with an irregular endometrial lining,13 verification of adenomyosis diagnosis was based on the histology results from operative material only. Adenomyosis was defined microscopically by the presence of ectopic endometrial glands and/or stroma in the myometrium, located 2.5 mm beyond the endometrial junction.30

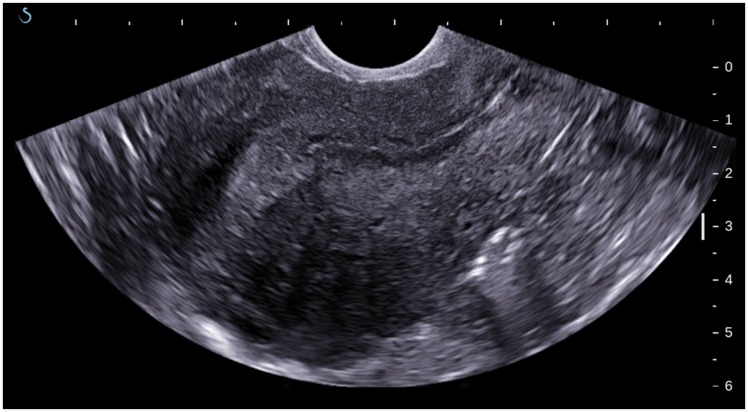

Figure 1.

B-mode image of uterus with adenomyosis: heterogeneous myometrial echo texture; asymmetry of the anterior and posterior wall.

Fifty-three patients who underwent hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy formed the main group. Their average age was 47 years old (32–58, 30–62) (median, 5–95th percentiles, minimum–maximum values). Adenomyosis was confirmed in 39 cases (A subgroup) and excluded in 14 cases (B subgroup) in the main group based on morphological examination of operative material (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

The results of morphological examination of operative material in A subgroup (with verified adenomyosis) (n = 39)

| Diagnosis | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Adenomyosis with leiomyoma, endometrium of proliferative and transitional type | 29/39 (74.4%) |

| Adenomyosis with leiomyoma and endometrial ovarian cyst, endometrium of proliferative type | 3/39 (7.7%) |

| Adenomyosis with leiomyoma and ovarian cyst (serous cystic adenoma) endometrium in proliferation phase | 3/39 (7.7%) |

| Adenomyosis with leiomyoma, serous cystic adenoma and endometrial ovarian cyst, endometrium in proliferative phase | 1/39 (2.6%) |

| Adenomyosis with serous cystic adenoma, endometrium in proliferation phase | 1/39 (2.6%) |

| Adenomyosis with endometrial ovarian cyst, endometrium in proliferative phase | 1/39 (2.6%) |

| Adenomyosis with peritoneal endometriosis | 1/39 (2.6%) |

Table 2.

The results of morphological examination of operative material in B subgroup (with excluded adenomyosis) (n = 14)

| Diagnosis | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Leiomyoma | 8/14 (57.1%) |

| Leiomyoma with uterine adnexa pathology: | 6/14 (42.9%) |

| Endometrial cyst | 1/6 |

| Serous cystic adenoma | 1/6 |

| Ovary fibroma | 1/6 |

| Follicular cyst | 1/6 |

| Bilateral hydrosalpinx | 1/6 |

| Peritubular cyst | 1/6 |

Fifty-six patients of reproductive age formed the control group. Criteria of inclusion into the control group were as follows: regular menstrual cycle; sonographically unremarkable myometrium (the lack of diffuse and focal pathology features, inflammatory diseases); the lack of conservative myomectomy and previous caesarean section; more than 6 months gap after the previous delivery; lack of contraceptive pill use. The average age of the control group was 30 years old (21–45, 18–50) (median, 5–95th percentiles, minimum–maximum values).

All patients underwent pelvic ultrasound according to the standard protocol, including transabdominal and transvaginal techniques. Ultrasound was performed before laparotomy in patients of the main group during the first phase of the menstrual cycle and on the day of admission to the hospital in cases of menopause. The study was performed on an Aixplorer (Supersonic Imagine, France) scanner with both curved array transabdominal probe with an operative frequency range 1–6 MHz and curved array transvaginal probe with an operative frequency range 3–12 MHz. Shear wave elastography was used in case of transvaginal examination with the endocavitary (transvaginal) transducer operating at a depth of up to 3 cm, which is defined by the technical limitations of this technique. Scanning was performed without additional compression movements of the hand and transducer. The minimum amount of pressure on the cervix as possible was applied. At each imaging plane, the probe was held steady for approximately 3–5 seconds (several frames) to obtain a stabilized image. The technique used was in accordance with previous literature published by Mitkov et al.31

Young’s modulus is one of the quantities for measuring the stiffness. Its unit, kPa, was used for stiffness assessment. The scale of Young’s modulus, which is used in gynaecological mode (180 kPa), was increased up to 300 kPa as required for the patients of the main group. Numerical values of Young’s modulus were measured in the areas of maximum myometrium stiffness. Sampling areas were chosen based on B-mode appearances for the patients of the main group. It is worth mentioning that the degree of myometrium stiffness according to the elastography data did not always correlate with the degree of myometrial heterogeneity on B-mode. Areas of interrogation were chosen to avoid fibroids in cases where both pathologies co-existed. Measurements were performed under conditions of full staining of the colour window (shear wave elastography imaging). The tissue stiffness of the examined area (kPa) was displayed with a colour map in real-time mode. Tissues of greater stiffness were characterized by high range of Young’s modulus, and mapped by red, green and yellow colours. The less stiff tissue with lower range of Young’s modulus was displayed predominately by a blue range of colours. The evaluation of tissue stiffness was performed in regions of interest (Q boxes), which were presented by round-shaped circles with adjustable diameter up to 10 mm. We used standard regions of interest (in shape and size). All images and data were saved in the machine’s storage for further assessment and processing.

The following numerical values (statistics) of Young’s modulus (E) were determined automatically in a region of interest (Q Box): the average value (Emean), minimum value (Emin), maximum value (Emax) and standard deviation (SD). Emean, Emax and SD were used for the analysis. Measurements were performed in three regions of interest (Q boxes). Then the average values of Emean, Emax and SD were determined.

Statistical analysis was performed with MedCalc Statistical Software. Quantitative data were displayed as median, 5th and 95th percentiles and minimum and maximum values. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare two independent groups, and the Friedman test was used for multiple comparison. The differences were considered to be significant with P < 0.05. The diagnostic potential of shear wave elastography was assessed by receiver operator characteristics (ROC) curve analysis. The ninety five percent confidence interval (95% CI) was presented for sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value.

Results

Retrospective analysis of shear wave elastography results against the results of morphological examination of operative material was performed.

It is worth noticing that shear wave elastography imaging (colour window) with adenomyosis was characterized by red, green and yellow colours (predominately heterogeneous staining due to high stiffness) (Figures 2 and 3). At the same time, unremarkable myometrium in all cases was mapped by blue colour (homogenous staining against the background of normative values of Young’s modulus) (Figure 4). However, the tint of colour range depended on the chosen scale of Young’s modulus. As mentioned above, the determined value of the scale in gynaecological mode is 180 kPa. In the course of the research, it became clear that increasing the scale (up to 300 kPa) did not influence Young’s modulus values, received from elastography in the interest area, but did alter the tint of the colour range.

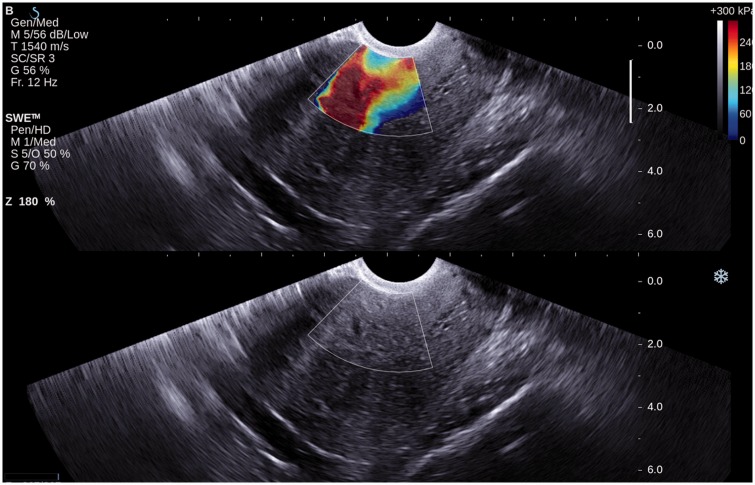

Figure 2.

Shear wave elastography of myometrium in a patient with confirmed adenomyosis (A subgroup). Grey-scale ultrasound in bottom row and overlaid shear wave elastography imaging in top row. Heterogeneous staining and high stiffness are demonstrated within a colour window (shear wave elastography imaging).

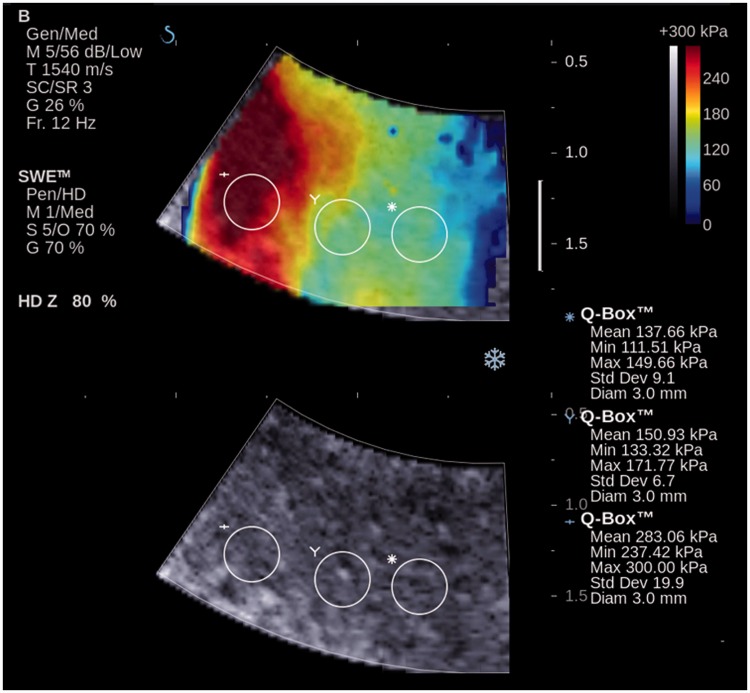

Figure 3.

Shear wave elastography of myometrium in a patient with confirmed adenomyosis (A subgroup) (ZOOM). Grey-scale ultrasound in bottom row and overlaid shear wave elastography imaging in top row. Colour window (shear wave elastography imaging) is characterized by heterogeneous staining. A wide range of Young’s modulus numerical values in three regions of interest (Q Box) are identified.

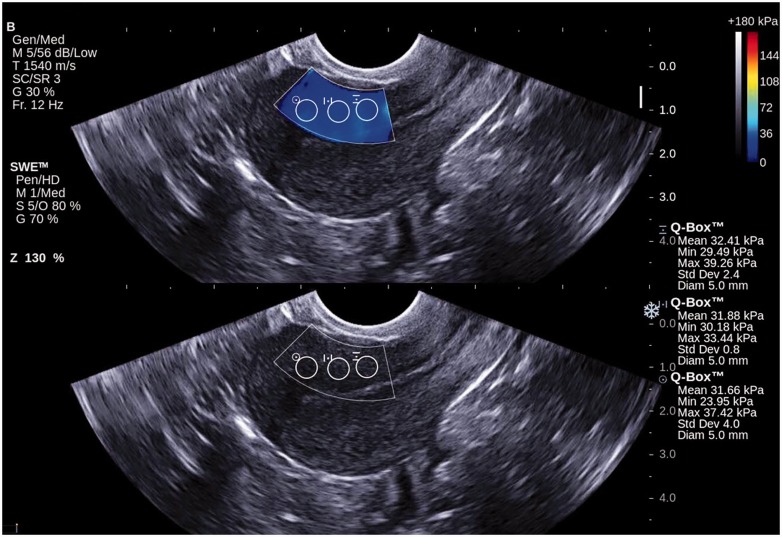

Figure 4.

Shear wave elastography of normal myometrium in a control group patient. Grey-scale ultrasound in bottom row and overlaid shear wave elastography imaging in top row. Colour window (shear wave elastography imaging) is characterized by homogenous staining. The results of Young’s modulus measurements in three regions of interest (Q-Box) are within the normal range.

Emean characteristics in A subgroup were within the range from 15.3 to 299.0 kPa, in B subgroup, they were from 10.6 to 65.7 kPa and in the control group, they were from 17.0 to 33.8 kPa (minimum and maximum values).

Emax characteristics in A subgroup were within the range from 20.4 to 300.0 kPa, in B subgroup, they were from 13.9 to 89.7 kPa and in the control group, they were from 19.8 to 44.9 kPa (minimum and maximum values).

SD characteristics in A subgroup were within the range from 2.3 to 43.5 kPa, in B subgroup, they were from 1.3 to 17.8 kPa and, in the control group, they were from 0.9 to 9.1 kPa (minimum and maximum values). Other statistics of Emean, Emax and SD are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Young’s modulus numerical values (kPa) (study and control groups)

| Groups and subgroups | Emean | Emax | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main group (n = 53): | |||

| A subgroup (n = 39) | 72.7a,b 22.6–274.2 | 94.8a,b 29.3–300.0 | 9.9a,b 2.6–26.3 |

| B subgroup (n = 14) | 28.3 12.7–59.5 | 33.6 16.0–80.8 | 3.0a 1.4–15.6 |

| Control group (n = 56) | 24.4 17.9–32.4 | 29.8 21.6–40.8 | 2.3 1.3–6.1 |

Note: first row – median, second row – 5–95th percentiles.

Significance of differences comparing with control group (P < 0.05).

Significance of differences comparing with B subgroup (P < 0.05).

The significant differences between the patients of A subgroup from the one side and patients of the control group and B subgroup from the other side were obtained when comparing Emean, Emax and SD. Difference between the B subgroup and control group were not significant with the exception of SD.

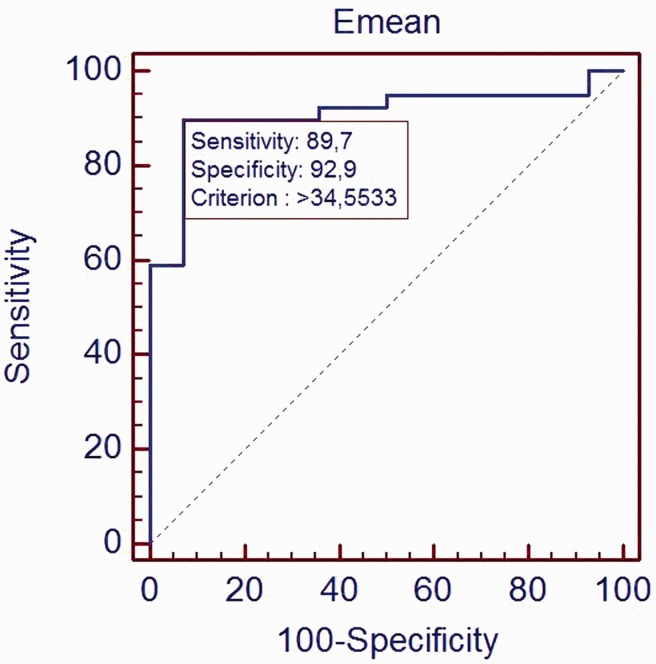

The ROC curve was generated using the Young’s modulus and the pathologic result (histological presence or absence adenomyosis). The Emean cut-off value was 34.6 kPa (Figure 5). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and area under curve (AUC) were 89.7% (75.8–97.1%) (95% CI), 92.9% (66.1–99.8%), 97.2% (85.5–99.9%), 76.5% (50.1–93.2%) and 0.908.

Figure 5.

ROC curve of Emean in adenomyosis prediction. AUC was 0.908.

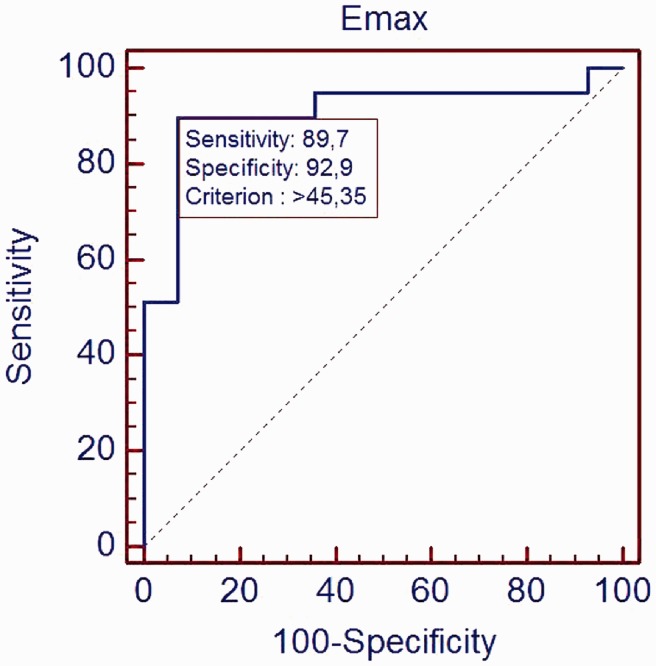

The Emax cut-off value was 45.4 kPa (Figure 6). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and area under curve (AUC) were 89.7% (75.8–97.1%) (95% CI), 92.9% (66.1–99.8%), 97.2% (85.5–99.9%), 76.5% (50.1–93.2%) and 0.907.

Figure 6.

ROC curve of Emax in adenomyosis prediction. AUC was 0.907.

Discussion

The sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound shear wave elastography in adenomyosis diagnosis was 89.7 and 92.9%. It is a sufficiently accurate primary noninvasive method for the diagnosis of adenomyosis in clinically suspicious cases. One should pay attention to the wide range of SD values with adenomyosis compared with normal myometrium. It can be argued that heterogeneity of myometrium seen with adenomyosis is often apparent on B-mode imaging based on subjective evaluation alone. However, with shear wave elastography, it seems possible to obtain statistically significant, objective information whilst reducing inter-operator variability.32

This study is corroborated by the publication of Tessarolo et al.33 who stresses the non-invasiveness of elastography, simplicity of its performance and the lack of significant extension of examination time. There are many studies presenting strain elastography only.34,35 Unfortunately, we cannot compare our results with strain elastography due to difference in technique methodology. According to Stoelinga et al.,34 strain elastography is able to identify clear discriminating characteristics of fibroids and adenomyosis, and elastography-based diagnoses are in excellent agreement with those of magnetic resonance imaging. A study by Frank et al.35 suggests that maximum strain ratio allows the operator to assess the presence of a uterine fibroid or adenomyosis and helps to differentiate between both focal findings.

There have been a number of studies presented since the first publication of EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Use of Ultrasound Elastography (Part 2),24 which include a study of uterine cervix and assessment of cervix premature softening. Present challenges for future studies and quantitative stiffness assessment of placenta, uterine fibroids, adenomyosis and cervix in view of shear wave elastography use in diagnosis of reproductive system diseases are discussed.36–40

Conclusion

Although this was one of the first studies of ultrasound shear wave elastography in the diagnosis of adenomyosis, the results are promising. The significant difference in stiffness of the myometrium with diffuse change in comparison with normal myometrium is presented. This technique may help to increase the accuracy of ultrasound in adenomyosis diagnosis, which could subsequently decrease the need for invasive diagnostic procedures, including hysterectomy. The addition of shear wave elastography to the transvaginal scan does not demand any significant lengthening of examination time; however, the main constraint at present is its field of operation, which is defined by the manufacturer and machine specifications, limited in this study to a depth of 3 cm. This would obviously have implications for large or axially orientated uteri. The technique is not suitable for women in whom transvaginal examination is contraindicated. Future studies with greater data should be considered to support the findings of this study and to confirm the proposed clinical benefit to patients and gynaecologists.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Sergey Sarkisov for his continued support during our research.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of Russian Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education. All patients submitted written consent.

Guarantor

SAC

Contributorship

SAC wrote the first draft and the final version. MDM, EM and VVM reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. VVM was the project supervisor.

References

- 1.Adamyan LV and Kulakov VI. Endometriosis: Guidelines for clinicians. Moscow: Medicine, 1998, p. 317.

- 2.Strizhakov AN and Davydov AI. Endometriosis: Clinical and theoretical aspects. Moscow: Medicine, 1996, p. 330.

- 3.Bulun SE. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 268–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kucera E, Hejda V, Dankovcik R, et al. Malignant changes in adenomyosis in patients with endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2011; 32: 182–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazandi M, Zeybek B, Terek MC, et al. Grade 2 endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from adenomyosis of the uterus: report of a case. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2010; 31: 719–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koshiyama M, Suzuki A, Ozawa M, et al. Adenocarcinomas arising from uterine adenomyosis: a report of four cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002; 21: 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu MI, Chou SY, Lin SE, et al. Very early stage adenocarcinoma arising from adenomyosis in the uterus. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 45: 346–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCausland AM. Extent and depth of adenomyosis – assessable? Fertil Steril 1993; 59: 479–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copperman AB, DeCherney AH, Olive DL. A case of endometrial cancer following endometrial ablation for dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol 1993; 82: 640–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popp LW, Schwiedessen JP, Gaetje R. Myometrial biopsy in the diagnosis of adenomyosis uteri. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993; 169: 546–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landekhovskiy YuD, Shnayderman MS. Value of different methods in genital endometriosis diagnostics. Obstet Gynaecol 2000; 1: 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dueholm M. Transvaginal ultrasound for diagnosis of adenomyosis: a review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2006; 20: 569–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molinas CR, Campo R. Office hysteroscopy and adenomyosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2006; 20: 557–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halis G, Mechsner S, Ebert AD. The diagnosis and treatment of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010; 107: 446–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazot M, Cortez A, Darai E, et al. Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathology. Hum Reprod 2001; 16: 2427–2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bazot M, Darai E, Rouger J, et al. Limitations of transvaginal sonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis, with histopathological correlation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002; 20: 605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bazot M, Malzy P, Cortez A, et al. Accuracy of transvaginal sonography and rectal endoscopic sonography in the diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007; 30: 994–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bromley B, Shipp TD, Benacerraf B. Adenomyosis: sonographic findings and diagnostic accuracy. J Ultrasound Med 2000; 19: 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinhold C, Atri M, Mehio A, et al. Diffuse uterine adenomyosis: morphologic criteria and diagnostic accuracy of endovaginal sonography. Radiology 1995; 197: 609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demidov VN, Adamyan LV, Khachatryan AK. Ultrasound diagnostics of endometriosis. Retrocervical endometriosis. Ultrasound Diagn Obstet Gynaecol Pediatr 1995; 2: 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levgur M. Diagnosis of adenomyosis: a review. J Reprod Med 2007; 52: 177–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinhold C, Tafazoli F, Wang L. Imaging features of adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update 1998; 4: 337–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidhu PS. Multiparametric ultrasound (MPUS) imaging: terminology describing the many aspects of ultrasonography. Ultraschall Med 2015; 36: 315–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cosgrove D, Piscaglia F, Bamber J, et al. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography. Part 2: Clinical applications. Ultraschall Med 2013; 34: 238–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ophir J, Alam SK, Garra BS, et al. Elastography: imaging the elastic properties of soft tissues with ultrasound. J Med Ultrason 2001; 29: 155–171–155–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garra BS. Imaging and estimation of tissue elasticity by ultrasound. Ultrasound Q 2007; 23: 255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bamber J, Cosgrove D, Dietrich CF, et al. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography. Part 1: Basic principles and technology. Ultraschall Med 2013; 34: 169–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linde VA and Tatarova NA. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis, clinical aspects, diagnosis, and treatment. Moscow: GEOTAR Media, 2010, p. 192.

- 29.Khmelnitskiy OK. Pathomorphological diagnostics of female diseases. Saint-Petersburg: Sotis, 1994, p. 480.

- 30.Dakhly DM, Abdel Moety GA, Saber W, et al. Accuracy of hysteroscopic endomyometrial biopsy in diagnosis of adenomyosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2016; 23: 364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitkov VV, Khuako SA, Sarkisov SE, et al. Quantitative estimation of the normal myometrium elasticity. Ultrasound Funct Diagn 2011; 5: 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitkov VV, Khuako SA, Ampilogova ER, et al. Assessment of the shear wave elastography reproducibility. Ultrasound Funct Diagn 2011; 2: 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tessarolo M, Bonino L, Camanni M, et al. Elastosonography: a possible new tool for diagnosis of adenomyosis? Eur Radiol 2011; 21: 1546–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stoelinga B, Hehenkamp WJ, Brolmann HA, et al. Real-time elastography for assessment of uterine disorders. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014; 43: 218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank ML, Schafer SD, Mollers M, et al. Importance of transvaginal elastography in the diagnosis of uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. Ultraschall Med 2016; 37: 373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitkov VV, Khuako SA, Sarkisov SE, et al. Value of shear wave elastography and elastometry in the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Ultrasound Funct Diagn 2011; 6: 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuksel MA, Kilic F, Kayadibi Y, et al. Shear wave elastography of the placenta in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Obstet Gynaecol 2016; 36: 585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muller M, Ait-Belkacem D, Hessabi M, et al. Assessment of the cervix in pregnant women using shear wave elastography: a feasibility study. Ultrasound Med Biol 2015; 41: 2789–2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez-Andrade E, Aurioles-Garibay A, Garcia M, et al. Effect of depth on shear-wave elastography estimated in the internal and external cervical os during pregnancy. J Perinat Med 2014; 42: 549–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furukawa S, Soeda S, Watanabe T, et al. The measurement of stiffness of uterine smooth muscle tumor by elastography. Springerplus 2014; 3: 294–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]