Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis, a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease with significant physical disability, affects women three times more frequently than men, often in their childbearing years. Parenthood decisions can be challenging, often affected by perceptions of their disease state, health care needs, and complex pharmacological treatments. Many women struggle to find adequate information to guide them on pregnancy planning, lactation, and early parenting in relation to their chronic condition. The expanded availability and choice of pharmacotherapies have supported optimal disease control prior to conception and enhanced physical capabilities for women to successfully overcome the challenges of raising children but require a detailed understanding of their risks and safety in the setting of pregnancy and breastfeeding. This review outlines the various situational challenges faced by rheumatologists in providing care to men and women in the reproductive age group interested in starting a family. Up to date evidence-based solutions particularly focusing on the safe use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic response modifiers to assist rheumatologists in the care of pregnant and lactating women with RA are reviewed.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy, biologics, DMARDs

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a lifelong, systemic autoimmune disease that affects women three times more frequently than men, often in their most productive and childbearing years.1 Annual incidence of 8.7 per 100,000 between the ages of 18 and 34 years further increases to 36.2 per 100,000 between the ages of 35 and 44 years.2 Understanding and addressing reproductive health-related problems are critical for health professionals engaged in their care. For women living with a chronic disease like RA on pharmacotherapy, the generally pleasant experience of planning parenthood can be faced with a number of uncertainties, challenges, and important decisions to take in the context of family planning. These relate not only to their ability to conceive, maintain successful pregnancy, heritability of the disease, and risks of their medication on their offspring but also guilt and self-doubt about their physical and functional capability as a parent and the ability of take care of their children, family, and themselves. There is undoubtedly a clear need to support these vulnerable women through this important stage of their lives.

Management of RA has revolutionized in recent years. Availability of novel therapies, such as biologic agents, and treatment paradigms, such as “treat to target”, have substantially improved treatment outcomes for patients with RA. Unfortunately, data on the safety of many of these medications are limited, and many may be contraindicated during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Careful planning is thus required to stabilize disease activity prior to conception and modify medication regimens. Although it was previously believed that >75% of patients experience remission of their disease during pregnancy, this was largely based on subjective parameters, patient/physician recall, small cohorts, and retrospective studies.3 Application of validated disease activity indices in recent studies has confirmed that only 20%–40% of patients with RA achieve remission by the third trimester. Although 50% may be considered to have low disease activity, nearly 20% will have worse or moderate-to-high disease activity during pregnancy and may require further therapeutic intervention.4 Many women also experience postpartum flares impairing their ability to take care of themselves and their infant.

Understanding the goals, both short term and long term, to ensure favorable pregnancy outcomes among women with RA is critical to provide appropriate counseling and education and develop management plans. Close communication between patients, their rheumatologists, and obstetricians is necessary to develop individualized treatment plans not only for treating active disease but also for maintaining disease remission during the preconception phase, pregnancy, and postpartum. We discuss in this comprehensive review the numerous challenges faced by rheumatologists in their care of men and women of childbearing potential and outline potential evidence-based solutions to assist them in this formidable task. The review is organized into sections based on the many different situations a rheumatologist can face and the best ways to address them.

Woman of reproductive potential with RA, not currently planning a family

For all women diagnosed with RA, it is important to get a reproductive history. For patients with childbearing potential, the desire to start or extend their family while on treatment should be ascertained. Women who are not currently interested in pursuing pregnancy but desire to conceive in the future should be appropriately counseled about the potential safety, risks, or teratogenicity of medications they are on for RA treatment. Contraception counseling thus becomes necessary and should be individualized.5 Pharmacokinetics of the drug should also be accounted for when counseling women about the timing for safe consideration of conception. This is discussed further in the “Medication counseling” section.

Woman with RA who wants to get pregnant

Fertility/family planning

Multiple factors impact the ultimate number of children a woman with RA will have. When evaluating parity of women with inflammatory arthritis compared to controls using the Norwegian Population Registry, it was more likely for women with inflammatory arthritis to remain childless compared to controls.6 The finding of reduced parity has been echoed in interviews/questionnaires of women with RA. Women who had RA diagnosed prior to having a child as compared to those with at least one child before RA diagnosis were less likely to have as many pregnancies or children.7 Twenty percent reported that RA was impacting their family-planning decisions with concerns that included functional ability to care for their child, medications, and possible heritability of RA. Those women who described RA as impacting family-planning decisions had fewer numbers of pregnancies and fewer numbers of children compared to those who did not between the ages of 19 and 44 years.7 From the standpoint of heritability, the risk for children of a patient with RA is three times that of the general population.8

In a longitudinal observational study of women with RA, among women who expressed interest in having more children, 55% reported having fewer children than desired.9 Women who reported concerns for disease or medications having a negative impact on the baby had fewer pregnancies. In those who had fewer children, there were higher rates of reported infertility, but there was no difference in the number of spontaneous or elective abortions.9

Fertility issues in RA are not associated with reduced ovarian reserve as evaluated by anti-Müllerian hormone levels.10 Among pregnant women enrolled in the Danish National Birth Cohort between 1996 and 2002,11 those with prevalent RA (onset prior to conception) were more likely to have been treated for infertility (9.8% vs 7.6%) and were more likely to have taken >12 months to conceive (25.0% vs 15.6%). A prospective cohort from the PARA study in the Netherlands included women who were pregnant or attempting to become pregnant.12 Of 245 patients, 205 (84%) became pregnant with 64 (31%) having a time to pregnancy over 12 months. Disease activity as measured by Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) was higher among women who did not conceive and those with longer time to pregnancy. Other factors associated with longer time to pregnancy included age, nulliparous state, and preconception use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and prednisone (>7.5 mg/day). Time to pregnancy was not found to be associated with rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-citrullinated protein antibody status or disease duration.12

Women with RA are reported to have high rates of infertility treatment, but this may be biased by other risk factors. In one study, women with RA were more likely to have been treated for infertility than those without RA (9.8% vs 7.6%) but were also older than women without RA.11 Another study demonstrated that assisted reproductive technology was more likely used for those with RA (5.6% vs 2.4%).13 Wallenius et al noted women with inflammatory arthritis utilizing assisted reproduction more often (3.9% vs 1.6% for reference subjects), but this was not statistically significant when adjusted for maternal age.14

Disease course of RA during pregnancy

Discussing with patients the impact of pregnancy on disease activity is helpful to form a basis for treatment recommendations. Observations of improvement in RA during pregnancy date back to Dr Hench.15 Larger cohorts have further clarified these earlier observations.4,16 However, there are limitations in using conventional measures of disease activity in pregnancy as these measures can be confounded by symptoms related to pregnancy itself.17 In a comparison of different disease activity scoring tools in pregnant women with RA vs healthy controls, DAS28-CRP without assessment of global health was the preferred tool for measuring RA disease activity in pregnant patients.17

Disability measures in the form of health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) have been demonstrated to decrease during pregnancy with lower measures of disability in the third trimester compared to immediately before pregnancy.16 In a description of pain, only 19% described worsening, while the majority improved (60%) over the course of pregnancy. However, remission was strictly defined by no swollen joints and no use of medications and occurred in only 16% during pregnancy.16 In one cohort, the DAS28 reduced during pregnancy.4 This is despite the fact that over one-third of women were not receiving any specific medications for RA in the third trimester.4

In the postpartum setting, disease activity is often seen to worsen when measured by different parameters, including joint counts, pain measures, and DAS.4,16 In the PARA cohort, 36% of women had a moderate flare, and an additional 4% a severe flare.4

In an updated report of the PARA study, in women with at least moderate disease activity in the first trimester, approximately half had no response, while the other had good/moderate response as defined by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) response criteria for pregnancy.18 In the postpartum state, 36% of women had severe-to-moderate deterioration in disease activity, while 64% had no deterioration.

Remission of disease activity during pregnancy is more likely in women who are RF negative.16 Individuals who responded during pregnancy, as defined by EULAR response criteria, were more likely to be both CCP and RF negative. Antibody status was not associated with flares postpartum.18

Pregnancy outcomes

Delivery by cesarean section has been demonstrated to be more common among women with RA across multiple cohorts with wide-ranging geographic locations.1,13,14,19,20 Cesarean sections were significantly more common in individuals who had moderate-to-high disease activity vs low disease activity.21

A few studies have demonstrated increased risk of preeclampsia among women with RA,13,20 while others have not been able to confirm this.1,14,19 It is unclear if this is reflective of different patient populations or preeclampsia case ascertainment.

The majority of studies demonstrate an increased risk of preterm births1,13,14,19,22 but not all.20 Increasing HAQ values during pregnancy have been associated with prematurity.23

There are variable data regarding the impact of RA on infant weight. Low birth weight was associated with RA in some studies.13,14,20,24 However, other studies have demonstrated no association.1,19,21 Disease activity in the third trimester is also known to be negatively associated with birth weight (P=0.025).21 Disability measures in the form of HAQ have also been associated with small-for-gestational age.23 Differences in levels of disease activity between the different cohorts may be a potential reason for variable results.

To date, there are no data to demonstrate an increased risk of congenital abnormalities among offsprings of women with RA, related to their disease.1,13

Medication counseling

There is significant complexity in terms of management of RA during pregnancy.25 Interpreting the effects of medications can also be more complicated by the fact that they are often used in combination. To add to the difficulty, there can be lack of agreement regarding medication recommendations between rheumatologists and obstetricians.26 Through experience and stakeholder feedback, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) learned that the pregnancy drug categories (A, B, C, D, X) were confusing and did not accurately and consistently communicate differences in degrees of fetal risk. These have been heavily relied upon by clinicians but are often misinterpreted and misused in that prescribing decisions have been made based on the pregnancy category, rather than an understanding of the underlying information that informed the assignment of the pregnancy category. The FDA believes that a narrative structure for pregnancy labeling, rather than a category system, is best able to capture and convey the potential risks of drug exposure based on animal or human data, or both. Therefore, the “final rule” requires the removal of the pregnancy categories A, B, C, D, and X from all drug labeling (effective from June 30, 2015).27 The final rule requires that the labeling include relevant information about pregnancy testing, contraception, and infertility. The final rule creates a consistent format for providing information about the risks and benefits of prescription drug and/or biological product use during pregnancy and lactation and by females and males of reproductive potential. These revisions will facilitate prescriber counseling for these populations.

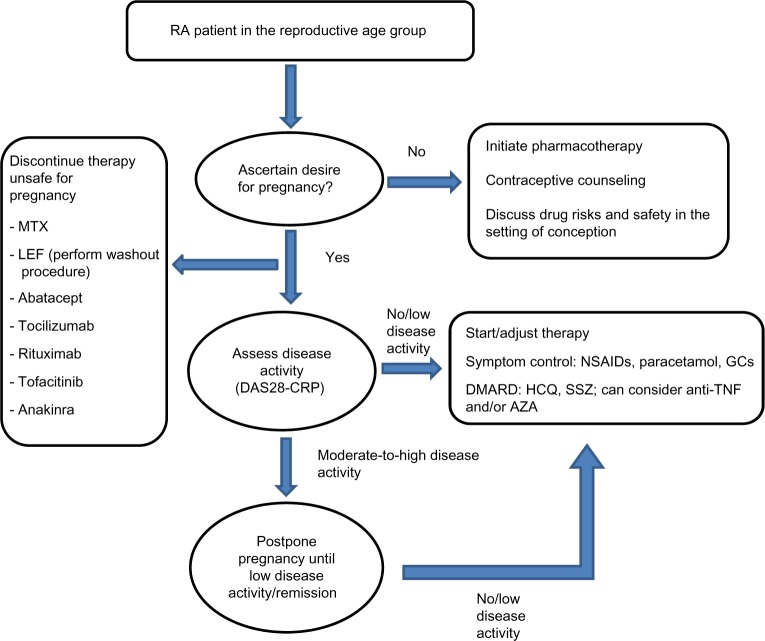

In the following sections, we discuss the risks and benefits and outline best practices in use of drug therapy in pregnant women with RA (Table 1 and Figure 1). In view of their previous extensive use, the previously established FDA category of the drug is also reviewed.

Table 1.

Approach to disease-modifying therapy for pregnant women with RA (or for women wishing to conceive)

| Preferred medications (if required) | Medications relatively safe to use (require individualized approach) | Contraindicated medications | Inadequate data to support safety |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids (B)a | TNFα inhibitors (B) | Methotrexate (X) | Anakinra (B) |

| NSAIDs (B)b | Azathioprine (D) | Leflunomide (X) | Abatacept (C) |

| Hydroxychloroquine (C) | Tocilizumab (C) | ||

| Sulfasalazine (B) | Tofacitinib (C) | ||

| Rituximab (C)c |

Notes: The US FDA pregnancy category125 for each drug is quoted in parenthesis: A: controlled human studies show no risk; B: no evidence of risk in studies; C: risk cannot be ruled out; D: positive evidence of risk; and X: contraindicated in pregnancy.

Counseling advised regarding possible cleft lip/palate abnormalities.

Avoid in third trimester due to risk of premature closure of ductus arteriosus.

Recommendation is to avoid in pregnancy due to hematologic abnormalities and infection risk.

Abbreviations: RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; FDA, Food and Drug Administration.

Figure 1.

Approach to management of patient with RA in reproductive age group.

Abbreviations: RA, rheumatoid arthritis; MTX, methotrexate; LEF, leflunomide; DAS28, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; GCs, glucocorticoids; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; SSZ, sulfasalazine; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; AZA, azathioprine.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

There are conflicting data regarding the risk of spontaneous abortion conferred by NSAIDs. In a case–control study evaluating miscarriages, NSAIDs were associated with miscarriage with the highest risk occurring with use during the week prior to miscarriage.28 This association was not found significant when adjusted for gestational age.29 A study utilizing Kaiser Permanente data demonstrated an increased risk of spontaneous abortion (hazard ratio [HR] 1.8, 1.0–3.2) with NSAID use, with higher risk associated with use closer to conception, and with >1 week of use.30 Reassuringly, a recent large prospective cohort study evaluating use of over-the-counter NSAID (2,780 pregnancies with over 40% reporting NSAID use) from last menstrual cycle to sixth week of pregnancy did not demonstrate any association between use of NSAIDs and spontaneous abortion.31

There has been no association of NSAIDs with congenital abnormalities or prematurity.28,32 In terms of birth weight, the majority of studies have found no association between low birth weight and NSAID use.28,32 However, when evaluating exposure to ibuprofen in the second trimester, there were findings of reduced birth weight, although other NSAIDs in this study did not demonstrate this association.32 It is unclear if this is an association unique to ibuprofen or a result of multiple comparisons.

In a meta-analysis, NSAIDs were demonstrated to significantly increase the risk of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus (odds ratio [OR] 15.04, 3.29–68.68).33 NSAIDs use is thus advised against in the third trimester, but they are considered category B earlier in the pregnancy.

Glucocorticoids (prednisone)

Prednisone is a commonly used medication in pregnancy with over half of one cohort of women with RA receiving corticosteroids during pregnancy.34

In the PARA cohort,21 prednisone use in patients with RA was associated with shorter gestational age (P<0.001) and as a result lower birth weight via multiple linear regression analysis (38.8 vs 39.9 weeks). Women with RA treated with prednisone were also more likely to deliver before 37 weeks than those not treated with prednisone (P=0.004).21 Two additional studies also demonstrated higher rates of prematurity in women treated with glucocorticoids (GCs) for varied indications, and both used pregnant women who had not been exposed to GCs and were not disease matched as the comparison group.35,36

There are conflicting data regarding the impact of GCs on miscarriage/fetal death. While in one study, there was no difference in miscarriage,36 another demonstrated higher occurrence of miscarriage with GCs.35

There are variable data with regard to the risk of congenital anomalies with prednisone exposure in pregnancy, especially cleft lip/palate. A study comparing 311 women with varied indications for GCs use in the first trimester with women without use did not note a difference in major anomalies. No occurrences of cleft lip or palate were identified.35 Similarly, there was no difference in major anomalies in another prospective cohort study (3.6% vs 2%, P=0.3).36 However, in a meta-analysis of six cohort studies and four case–control studies, a marginally increased risk of major malformations after first-trimester exposure to corticosteroids was noted in addition to a significantly higher odds for oral clefts (OR 3.35, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.97–5.69).36 Women should be counseled about this small but increased risk to make an informed decision regarding first-trimester GC use, as a similar incidence of oral clefts has been demonstrated in animal studies.37 The FDA considers GCs as category B.

Methotrexate

The absolute contraindication to methotrexate (MTX) (category X) during pregnancy is secondary to the risk of spontaneous abortion and MTX embryopathy characterized by a combination of abnormalities impacting the heart, central nervous system, and skeleton.38 There are case reports of exposure to low doses of MTX during the first trimester without untoward side effects,39,40 but unfortunately, there does not appear to be a low enough dose that a pregnant patient can be counseled on that the MTX exposure will not pose any risk.

In the setting of accidental exposure to MTX, women can be counseled using observational data. The largest available dataset comes from the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS) and European Network of Teratology Information Services.41 Pregnancy outcomes in women taking MTX (≤30 mg/week) either after conception or within 12 weeks before conception were evaluated in a prospective observational multicenter cohort study and compared to disease-matched women and women without autoimmune diseases. There were 136 pregnancies exposed during preconception and 188 exposed following conception. The median exposure after last menstrual cycle was 4.3 weeks with only two women exposed past the first trimester. Cumulative incidence of spontaneous abortions was higher at 42.5% among those exposed postconception when compared to disease-matched (HR 2.1, 1.3–3.2) and nondiseased comparison groups (HR 2.5, 1.4–4.3). For women exposed prior to conception, risk was no higher than the two comparison groups. Major birth defects were more common in women with MTX exposure postconception as compared to nondiseased comparison group (OR 3.1, 1.03–9.5). However, there was no significant increase when compared to disease-matched controls. There was no difference in birth defects among women with exposure only in preconception and the two comparison groups. No birth defects in either exposure group were consistent with MTX embryopathy.41

A systematic review from 2009 reported similar results in 101 cases of MTX exposure during the first trimester.42 Half resulted in live births. This study also demonstrated relatively low rates of congenital abnormalities with none thought to represent MTX embryopathy. Nineteen pregnancies ended as spontaneous abortions.42

While this information could be used in the setting of an inadvertent exposure, MTX should be discontinued prior to conception when pregnancy is being planned (category X). If a woman is receiving MTX, she should be using concomitant contraception.

Hydroxychloroquine

Much of the data regarding the safety of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) for RA are extrapolated from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In an evaluation of 114 pregnancies with majority occurring in women with SLE (RA in 22%) with exposure to HCQ, there was no difference in congenital anomalies between those exposed to HCQ and healthy controls.43 There was evidence of higher rates of preterm delivery and lower birth weight, but this is confounded by exposed groups having underlying disease and additional medications.43

A meta-analysis utilized four observational studies of women with connective tissue disease with HCQ exposure as compared to non-HCQ-exposed controls. There was no significant risk of spontaneous abortion, fetal death, prematurity, live births, or congenital defects.44

In a randomized, controlled study that assessed the need for HCQ during lupus pregnancy and safety, 22 consecutive pregnant women with lupus were randomized to HCQ vs placebo.45 Women exposed to HCQ did not experience any flares. Delivery age and Apgar scores were higher in the HCQ group. Neonatal examination did not reveal congenital abnormalities nor did a neuroophthalmological and auditory evaluation at 1.5–3 years of age. Despite the small number of patients studied, beneficial effects of HCQ were noted as measured by lupus disease activity measures developed for pregnancy (SLE disease activity index) and decrease in prednisone dose with no detriment to patients’ health. In addition, HCQ has been associated with benefit of improved obstetrical outcomes in the setting of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.46 HCQ is labeled as category C, and if needed to control disease activity, can be safely continued during pregnancy.47

Sulfasalazine

Conclusions regarding safety of sulfasalazine are drawn primarily from the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) literature. In a meta-analysis evaluating 642 women with IBD with exposures to sulfasalazine, mesalazine, and olsalazine, there were no findings of increased risk of congenital abnormalities, spontaneous abortions, preterm delivery, or low birth weight.48 The largest individual study included in this meta-analysis utilized a Danish cohort of children born to mothers with Crohn’s disease with 179 births representing exposure to sulfasalazine. There were no findings of increased risk of low birth weight, prematurity, or congenital abnormalities when comparing to women with Crohn’s disease without exposure.49

There are limited case reports of adverse outcomes for infants exposed to sulfasalazine, but it is difficult to attribute causality from these reports. These include reports of fetal hemolytic anemia and congenital neutropenia.50,51

Sulfasalazine is another disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) that can be continued during pregnancy with a category B rating.52

Leflunomide

Similar to MTX, leflunomide (LEF) is classified as a category X drug.53 It should be avoided in women who will be pursuing pregnancy even in the upcoming years due to its long half-life.

In a study by the OTIS Collaborative Research Group, 64 individuals with LEF exposure were identified and were compared to disease-matched controls and healthy controls. The latest exposure was 8.6 weeks after conception. The vast majority underwent a cholestyramine washout procedure (95.3%). Live births occurred in 87.5%, while 7.8% had spontaneous abortions, and 1.6% elective abortion. When adjusted for other factors, there was no difference in birth weight or gestational age based on LEF exposure. Overall, there were no differences in occurrence of major structural abnormalities. There were three defects identified in infants with LEF exposure: occult spinal dysraphism, unilateral uretero pelvic junction obstruction with subsequent multicystic kidney disease, and microcephaly.54

An additional study by OTIS with 45 women was subsequently published that did not meet the prior study’s inclusion criteria. This study included women enrolled after 20 weeks of gestation, those who had an indication beyond RA, or did not have confirmatory elimination of LEF with use within the prior 2 years. There were two spontaneous abortions, but the remaining were live infants. There were two infants with major anomalies: aplasia cutis congenita and Pierre-Robin sequence, spina bifida occulta, patent ductus arteriosus, chondrodysplasia punctata, and congenital heart block. Two separate patients had a similar pattern of minor anomalies of a short nose, flat nasal bridge, and long philtrum. There were increased rates of preterm delivery in women exposed to LEF during pregnancy as compared to women who were exposed only prior to conception.55

The category X status of LEF requires that significant caution be used in women who are of childbearing age.

Azathioprine

The pregnancy rating of azathioprine (AZA) is category D, but it has been utilized in other diseases such as IBD.56 A recent meta-analysis of women with IBD combined four studies that evaluated AZA/6-mercaptopurine use in 312 pregnant women. When compared to pregnant women with IBD with no other medications as well as women with IBD treated with other medications, there was no increased risk of prematurity or low birth weight. When evaluating spontaneous abortion compared to other medications for IBD, there was no increased risk noted. However, for congenital abnormality, while no increased risk was noted when compared to women with IBD treated with other medications, an increased risk was noted when compared to women with IBD not on medications (OR 2.95, 95% CI 1.03–8.43).57 While there is reassuring data regarding the use of AZA in pregnancy, it is still considered category D.

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors/anti-TNF therapy

Exposure to anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents in pregnancy has been linked with VACTERL (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, limb abnormalities) association in case reports58 and after a review of the FDA database for congenital anomalies in the setting of TNF exposure.59 There were 41 children with a total of 61 anomalies in the setting of exposure to etanercept or infliximab. One child was diagnosed with VACTERL association with 59% of children having at least one anomaly associated with VACTERL association.59 However, these data are in contrast to more recent data. Utilizing the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register, 130 pregnancies in 118 women were identified who were exposed to anti-TNF agents either prior to or at conception.60 There were four congenital manifestations: congenital dislocation of the hip and pyloric stenosis in those with exposure to anti-TNF at conception and winking jaw syndrome and a strawberry birth mark in those who had prior TNF exposure.60 In a prospective evaluation of the Israeli Teratology Information Service over a 10-year period,61 83 individuals were identified to be exposed to TNF inhibitors (infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab) and were compared to disease-matched and women with no known teratogen exposures during pregnancy. There were no children with VATER/VACTERL association and overall no differences in congenital anomalies.61 In the PIANO registry of pregnant women with IBD, TNF inhibitors were not associated with increased risk of congenital abnormalities.62 Utilizing the European Network of Teratology Information Services, major birth defects were reported in 5% of exposed as compared to 1.5% in nondiseased controls with borderline significant risk.63 In terms of fetal abnormalities in another cohort of individuals exposed to infliximab, one patient had Tetralogy of Fallot, one child had intestinal malrotation, and one twin had delayed development and hypothyroidism.64 In the TREAT registry for Crohn’s disease, there were 142 pregnancies with exposure to infliximab with healthy babies in 92.4% compared to 85.3% receiving other treatments.65 In the OTIS RA Pregnancy Project, a total of 32 patients were compared to women with RA but not on anti-TNF and women without RA. There was no difference in congenital abnormalities between the three groups. Preterm delivery was the same between the RA groups but higher compared to those without RA. Birth weight in full-term infants was lower in both RA groups compared to non-RA. One defect in anti-TNF group was spontaneous abortion of a fetus with trisomy 18.66

TNF inhibitors have not been associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion in multiple cohorts.62–64 Spontaneous abortions occurred in 24% of those who received TNF inhibitors at conception (excluding those who were also receiving MTX or LEF) as compared to 17% in those with prior TNF exposure, and 10% of those who were not exposed (based on low numbers, only ten pregnancies included in the nonexposed group).60

There have been contrasting reports regarding risk of prematurity and TNF inhibitors with some demonstrating increased risk,63 while others have not been able to confirm this.60,62

There are differences between the individual TNF inhibitors in terms of placental transfer. In an evaluation of women with IBD who received TNF inhibitors during pregnancy, maternal blood levels were compared to infant blood levels and cord levels. The infants of women who received certolizumab had the lowest rates with all infants having undetectable concentrations as measured by polyethylene glycol. In contrast, for infliximab, every infant had an infliximab level from cord or blood that was higher than the mother’s concentrations, the median ratio of cord to mother’s blood being 160%. Infliximab remained detectable for multiple months in the majority of children, and ultimately became undetectable at 7 months. For adalimumab as well, the levels were elevated with a median ratio of 153%. Despite these differences, there were no congenital abnormalities reported.67

An increased number of infections in infants in the first year of life was noted for combination of TNF inhibitors and thiopurines as compared to those who were unexposed.62 The devastating impact of infection is demonstrated in an infant who died from a disseminated BCG infection at 4.5 months following immunization at 3 months in the setting of the child’s mother receiving infliximab for IBD during pregnancy.68

Package inserts for TNF inhibitors include a pregnancy risk factor B.69–73

Abatacept

Based on expert opinion, it is recommended that attempts to conceive should occur 14 weeks after the last abatacept dose which would correlate with five half-lives of abatacept.74 The largest series of maternal exposure to abatacept is 151 pregnancies with 86 live births.75 In 59, the pregnancy resulted in an abortion, 40 spontaneous (over half of patients were also receiving MTX) and 19 elective. There were seven congenital anomalies identified: cleft lip/palate, congenital aortic anomaly, meningocele, pyloric stenosis, skull malformation, trisomy 21 with premature rupture of membranes at 17 weeks with subsequent infant death, and ventricular septal defect and congenital arterial malformation. Two of the mothers were also receiving LEF and mycophenolate. Abatacept is considered a pregnancy risk factor C.76

Rituximab

Rituximab is categorized as pregnancy category C, and it is recommended to wait 12 months after exposure to rituximab before attempting conception.77 The largest cohort of rituximab pregnancy exposures for varied disease conditions utilizing a drug safety database included 153 pregnancies with known outcomes.78 Live births occurred in 59%. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 21%, while 18% were elective terminations. Of the live births, 24% were premature with one death at 6 weeks of unclear etiology. There were eleven infants with hematologic abnormalities, including leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia, and a separate four patients suffered neonatal infection. There were two reports of congenital abnormalities including one clubfoot and one cardiac malformation. Rituximab is detectable in infant blood and cord blood.78 In one case report, B-cells were undetectable in cord blood following exposure to rituximab in the mother for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.79 Rituximab is rated as category C.

Anakinra

While anakinra is rated as pregnancy category B, very little information is available on its effects in pregnancy.80 Evaluating women with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes, nine births were identified with anakinra exposure. There was a single fetus of a twin pregnancy that died in the setting of renal agenesis with an NLRP3 mutation. Otherwise, there were no episodes of prematurity for live births.81 In three patients with Still’s disease, there are case reports of successful pregnancies with anakinra exposure.82,83

Tocilizumab

Similarly, there is insufficient information with regard to tocilizumab use and pregnancy. It is categorized as a risk factor C.84 A total of 33 pregnancies with tocilizumab exposure have been reported with eleven term deliveries. In seven, a spontaneous abortion occurred with five of those also receiving MTX. An additional 13 had an elective abortion, while the outcome in two was unknown. There was one death that occurred at 3 days due to acute respiratory distress syndrome following intrapartum hemorrhage due to placenta previa.85

Tofacitinib

There are no published data regarding tofacitinib exposure and pregnancy outcomes. It is categorized as risk factor C.86

Woman with RA who calls with positive pregnancy test

In the setting of a positive pregnancy test for a woman on treatment for RA, an individualized discussion for each medication should occur. Also, the possibility but uncertainty of improved disease activity over the course of pregnancy should be discussed. Certain medications will absolutely need to be discontinued, including MTX and LEF.38,53 Decisions to continue pregnancies should be based on extensive counseling to include the possibility of healthy pregnancy despite medication exposure.

Specifically for LEF, in the event of pregnancy, it is recommended that patients receive cholestyramine to eliminate the drug (washout procedure). A dose of 8 g three times daily for a total of 11 days followed by checking the plasma level of LEF with a goal of <0.02 mg/L on two occasions separated by 2 weeks, with consideration for additional cholestyramine if it remains elevated, is recommended.87

Woman with RA who is pregnant calls with flare

While fortunately some individuals have improvement in disease activity, not all patients will have improvement, and some will suffer flare during pregnancy. Corticosteroids are an initial first step in pregnancy, and when possible, intra-articular administration is indicated to limit systemic side effects. NSAIDs can also be another option, but as described in the following section, they need to be used with caution particularly in the third trimester.

Woman with RA who is considering breastfeeding

The decision about breastfeeding must be individualized to take into account the wishes of the mother, health benefits of breastfeeding, the disease activity of RA, and the associated need for medications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Approach to medications for women with RA who are breastfeeding

| Preferred medications (if required) | Insufficient data to support safe use | Contraindicated medications |

|---|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids | TNFα inhibitors | Methotrexate |

| NSAIDs | Anakinra | Leflunomide |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Abatacept | Azathioprineb |

| Sulfasalazinea | Rituximab | |

| Tocilizumab | ||

| Tofacitinib |

Notes:

Caution is advised in the setting of prematurity, hyperbilirubinemia, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

Avoidance is recommended by the manufacturer and expert opinion which is primarily based on theoretical risk.

Abbreviations: RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In a prospective cohort of pregnant women with RA where disease activity was assessed from the third trimester to 6 months postpartum, worse disease activity was noted in first-time breastfeeding women at 6 months postpartum compared to non-breastfeeding women.88

A resource to help guide clinicians and patients about the safety of drug use during lactation is the Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed), a part of the Toxicology Data Network from the National Institutes of Health (http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/lactmed.htm). Individual drugs can be searched on this portal, and the resource is updated monthly.

For the management of an acute flare of RA in a lactating mother, prednisone seems to be a reasonable option. Prednisolone levels in breast milk reach 5%–25% of serum levels, with estimates of infants absorbing 0.1% of the mother’s dose that, even at high doses, are an insignificant amount compared to endogenous production.89

NSAIDs are also an alternative for pain management. Commonly used NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, diclofenac, indomethacin, naproxen, and piroxicam are compatible with breastfeeding per the American Academy of Pediatrics.90 Ibuprofen demonstrates low rates of transfer with a theoretical infant dose of 68 μg/kg/day, which corresponds to 0.2% of the pediatric dose.91 It is also a good option due to its short half-life and low levels reached in breast milk.92

In terms of DMARDs that can be utilized during breastfeeding, HCQ is felt to be a safe option. It has not been associated with any visual abnormalities or infections in infants over the first year of life.93 Further, no abnormalities were noted in flash electroretinography among children exposed in utero and during lactation.94 Two women had breast milk values of HCQ evaluated; it was detectable in both with ingestion estimated at 0.06–0.2 mg/kg/day.95

While sulfasalazine metabolites are present in breast milk, there was no increase in serum values of children for either sulfasalazine or its metabolites. These levels were low enough as to have no impact on displacement of bilirubin.96 In one case report, an infant who was exclusively breastfed developed bloody diarrhea, while the mother was using sulfasalazine for ulcerative colitis.97 Infants should thus be monitored for diarrhea. The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends caution in infants who are premature, have glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, or have jaundice.90

In terms of AZA, the data available are primarily from patients with IBD. Very low amounts appear in the breast milk. In a study of four women, the metabolite 6-mercaptopurine could not be detected, and the infant level corresponds to 0.09% of the maternal dose.98 In another study, 6-mercaptopurine could only be detected in two of 31 breast samples (from ten women), both from the same woman. There were no complications noted in the ten children.99 In a long-term follow-up of children who were breastfed while mother was taking AZA (eleven mothers, 15 infants), no difference in development, infection, or hospitalizations was demonstrated compared to mothers who did not take AZA.100

There is a possibility of neutropenia in the infant exposed to AZA. In an abstract describing 20 newborns with blood counts performed after 2–3 weeks of breastfeeding, one patient had asymptomatic neutropenia at 2 weeks, but the AZA metabolites could not be detected. The neutropenia continued after breastfeeding was stopped for 15 days and normalized after 3.5 months. The child had no complications of infection.101

Based on the prescription insert, MTX should be avoided during breastfeeding.38 There are case reports of low levels present in breast milk. In one patient treated for cholangiocarcinoma, there were very low levels with milk-to-plasma concentrations of 0.08:1.102 In a woman treated for RA with 25 mg subcutaneous weekly, MTX was detectable in the milk but at low values of 3.4 μg/kg/day consistent with 1% of the mother’s weight-adjusted dose with no adverse outcomes.103 However, due to the concern for side effects particularly cytopenias, MTX would not be desirable particularly when alternatives are available. There are no data regarding LEF and breastfeeding, and as such, it is not recommended.53

While the prescription inserts of TNF inhibitors recommend that they should not be used during pregnancy, some expert opinions consensus do support their use in particular patient scenarios.104 Very low rates of TNF inhibitors are present in breast milk and in some cases undetectable.105,106 When detectable, the levels are quite low. In an evaluation of three patients, infliximab was detectable in the milk at 1/200 as compared to mother’s serum.107 Adalimumab was detectable in a single patient’s breast milk with peak on day 6 with the level being <1/100 compared to the mother’s serum.108 In a child born to a woman who remained on etanercept throughout pregnancy who was exclusively breastfed, the cord blood level was 1/30 of the mother’s blood level, and this significantly declined in the weeks following pregnancy (81 ng/mL at birth, 21 ng/mL at 1 week, 2 ng/mL at 3 weeks, and undetectable at 12 weeks) despite ongoing breastfeeding.109 Other case reports have also confirmed the low values of etanercept in breast milk.110,111

There are insufficient data to make recommendations regarding other biologics or JAK inhibitors. There is a single report of anakinra exposure during pregnancy and breastfeeding with a good outcome for the infant.83

Male patient with RA who wants to start a family

The diagnosis of RA in a father is not associated with poor outcomes such as preterm birth or fetal growth measures for their children.22 However, there may be implications with regard to medications used for RA management on birth outcomes (Table 3). Overall, when evaluating risk of paternal DMARD exposure near conception, there was no associated risk identified of preterm delivery, low birth weight, or significant congenital abnormalities compared to reference populations utilizing Norwegian birth data and DMARD registry studies.112 The medication exposures in this cohort included MTX, sulfasalazine, LEF, AZA, HCQ, and TNF inhibitors.

Table 3.

Medication management in male patient with RA interested in planning a family

| Drug | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Methotrexate | Hold 3 months prior to contraception due to sperm life cycle |

| Sulfasalazine | If difficulty with fertility, consider holding as it has been associated with reversible infertility |

| Azathioprine | No data to suggest adverse outcomes |

| Leflunomide | Insufficient data, but no adverse outcomes reported |

| TNFα inhibitors | Varied data regarding spermatogenesis but overall favorable outcomes |

| Rituximab | Insufficient data, but adverse outcomes reported |

| Abatacept | Insufficient data, but adverse outcomes reported |

Abbreviations: RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

There are variable data regarding the impact of MTX on male fertility. A young male developed severe oligospermia coincident with MTX use on two different occasions, which normalized after discontinuation of its use.113 However, in another case series of ten patients with psoriasis treated with MTX, there were no differences in semen analysis results compared to patients treated with topical corticosteroids, and the analysis showed that the semen was actually more frequently found to be normal in the MTX-treated group (P=0.04).114

The prescription insert for MTX advises waiting for at least 3 months after discontinuing MTX before attempting to conceive.38 This 3-month timeframe corresponds to the length of the spermatogenic cycle (74 days).115 Fortunately, recent data from a prospective cohort study on paternal MTX exposure demonstrated no increase in major birth defects, spontaneous abortions, birth weight, or low gestational age at delivery.116

Sulfasalazine has been associated with decreased sperm count, motility, and abnormal sperm morphology.117 If a male patient is having difficulty with fertility, and if disease activity will allow, sulfasalazine could be held to see if this results in successful conception attempt.

AZA/mercaptopurine paternal exposure before conception has not been associated with congenital abnormalities.118,119 No significant difference was reported in spontaneous abortions, birth weight, or time to conception between men with IBD who had received AZA/mercaptopurine for 3 months prior to conception and those who did not.119

Data on paternal exposure to LEF are limited. In one man who continued LEF throughout his partner’s pregnancy, there was a normal-term pregnancy.120

There are conflicting data on the impact of TNF inhibitors on spermatogenesis. Among ten men with IBD receiving infliximab, there was an increase in semen volume following infliximab infusion in comparison to before infusion.121 Overall, there were reduced percentages of normal oval forms and sperm motility in these patients with IBD exposed to infliximab.121 A man treated with adalimumab was noted to have oligoasthenozoospermia.122 With cessation of adalimumab, sperm concentration and morphology returned to normal, while motility continued to be low. Sperm abnormalities are common in healthy men but more pronounced in patients with active spondyloarthropathy. A study reported significantly reduced sperm motility and vitality among patients with active spondyloarthropathy compared to those with inactive disease on longstanding anti-TNF therapy.123 There were no differences in sperm concentration or morphology. When comparing healthy controls and anti-TNF-treated patients, there was no difference in sperm quality.123 Ongoing use of anti-TNF by a man who desires pregnancy with their partner is supported by this study.

Overall, the outcomes with paternal TNF exposure have been positive. In the TREAT registry for infliximab for management of Crohn’s disease, there were no differences in the percentage of live births or congenital abnormalities for paternal exposures to TNF inhibitors vs other treatments. 65 Four patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with infliximab had six healthy children.124 In a total of ten pregnancies with male partner with exposure to infliximab, nine pregnancies resulted in live births with one miscarriage.64

There is limited information about paternal exposure to rituximab. Of eleven pregnancies, seven had normal live births, two were still ongoing at the time of the report, and two had miscarried.78

Of ten men whose partners became pregnant while exposed to abatacept,75 nine pregnancies resulted in live births, and one ended as an elective abortion. There were no congenital abnormalities and no fetal deaths.75

Conclusion

Family planning both for female and male patients with RA must be taken into account by rheumatologists for developing plans of care. Extensive counseling is needed to help guide patients and primarily is dependent on observational data. This underscores the importance of reporting outcomes of pregnancies to help better inform future patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Mayo Clinic Margaret Harvey Schering Clinician Career Development Award Fund for Arthritis Research. The sponsors of this grant did not have any involvement with study design, data collection, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Wallenius M, Salvesen KA, Daltveit AK, Skomsvoll JF. Rheumatoid arthritis and outcomes in first and subsequent births based on data from a national birth registry. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(3):302–307. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955–2007. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1576–1582. doi: 10.1002/art.27425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cush JJ, Kavanaugh A. Editorial: pregnancy and rheumatoid arthritis–do not let the perfect become the enemy of the good. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(3):299–301. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Man YA, Dolhain RJ, van de Geijn FE, Willemsen SP, Hazes JM. Disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: results from a nationwide prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1241–1248. doi: 10.1002/art.24003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Østensen M. Contraception and pregnancy counselling in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(3):302–307. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallenius M, Skomsvoll JF, Irgens LM, et al. Parity in patients with chronic inflammatory arthritides childless at time of diagnosis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41(3):202–207. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2011.641582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz PP. Childbearing decisions and family size among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(2):217–223. doi: 10.1002/art.21859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frisell T, Holmqvist M, Kallberg H, Klareskog L, Alfredsson L, Askling J. Familial risks and heritability of rheumatoid arthritis: role of rheumatoid factor/anti-citrullinated protein antibody status, number and type of affected relatives, sex, and age. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(11):2773–2782. doi: 10.1002/art.38097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clowse ME, Chakravarty E, Costenbader KH, Chambers C, Michaud K. Effects of infertility, pregnancy loss, and patient concerns on family size of women with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(5):668–674. doi: 10.1002/acr.21593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brouwer J, Laven JS, Hazes JM, Schipper I, Dolhain RJ. Levels of serum anti-Mullerian hormone, a marker for ovarian reserve, in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65(9):1534–1538. doi: 10.1002/acr.22013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jawaheer D, Zhu JL, Nohr EA, Olsen J. Time to pregnancy among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(6):1517–1521. doi: 10.1002/art.30327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brouwer J, Hazes JM, Laven JS, Dolhain RJ. Fertility in women with rheumatoid arthritis: influence of disease activity and medication. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(10):1836–1841. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nørgaard M, Larsson H, Pedersen L, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and birth outcomes: a Danish and Swedish nationwide prevalence study. J Intern Med. 2010;268(4):329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallenius M, Skomsvoll JF, Irgens LM, et al. Pregnancy and delivery in women with chronic inflammatory arthritides with a specific focus on first birth. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(6):1534–1542. doi: 10.1002/art.30210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hench PS. The ameliorating of pregnancy on chronic atrophic (infectious, rheumatoid) arthritis, fibrositis and intermittent hydrarthrosis. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1938;13:161–167. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrett JH, Brennan P, Fiddler M, Silman AJ. Does rheumatoid arthritis remit during pregnancy and relapse postpartum? Results from a nationwide study in the United Kingdom performed prospectively from late pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(6):1219–1227. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199906)42:6<1219::AID-ANR19>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Man YA, Hazes JM, van de Geijn FE, Krommenhoek C, Dolhain RJ. Measuring disease activity and functionality during pregnancy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(5):716–722. doi: 10.1002/art.22773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Man YA, Bakker-Jonges LE, Goorbergh CM, et al. Women with rheumatoid arthritis negative for anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide and rheumatoid factor are more likely to improve during pregnancy, whereas in autoantibody-positive women autoantibody levels are not influenced by pregnancy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(2):420–423. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.104331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed SD, Vollan TA, Svec MA. Pregnancy outcomes in women with rheumatoid arthritis in Washington State. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(4):361–366. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin HC, Chen SF, Chen YH. Increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(4):715–717. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.105262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Man YA, Hazes JM, van der Heide H, et al. Association of higher rheumatoid arthritis disease activity during pregnancy with lower birth weight: results of a national prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(11):3196–3206. doi: 10.1002/art.24914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rom AL, Wu CS, Olsen J, et al. Fetal growth and preterm birth in children exposed to maternal or paternal rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(12):3265–3273. doi: 10.1002/art.38874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bharti B, Lee SJ, Lindsay SP, et al. Disease severity and pregnancy outcomes in women with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists Autoimmune Diseases in Pregnancy Project. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(8):1376–1382. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowden AP, Barrett JH, Fallow W, Silman AJ. Women with inflammatory polyarthritis have babies of lower birth weight. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(2):355–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Østensen M, Khamashta M, Lockshin M, et al. Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs and reproduction. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):209. doi: 10.1186/ar1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panchal S, Khare M, Moorthy A, Samanta A. Catch me if you can: a national survey of rheumatologists and obstetricians on the use of DMARDs during pregnancy. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(2):347–353. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products; requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling. [Accessed October 10, 2015]. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2014/12/04/2014-28241/content-and-format-of-labeling-for-human-prescription-drug-and-biological-products-requirements-for.

- 28.Nielsen GL, Sorensen HT, Larsen H, Pedersen L. Risk of adverse birth outcome and miscarriage in pregnant users of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: population based observational study and case-control study. BMJ. 2001;322(7281):266–270. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7281.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen GL, Skriver MV, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. Danish group reanalyses miscarriage in NSAID users. BMJ. 2004;328(7431):109. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7431.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li DK, Liu L, Odouli R. Exposure to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during pregnancy and risk of miscarriage: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2003;327(7411):368. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7411.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edwards DR, Aldridge T, Baird DD, Funk MJ, Savitz DA, Hartmann KE. Periconceptional over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug exposure and risk for spontaneous abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(1):113–122. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182595671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nezvalová-Henriksen K, Spigset O, Nordeng H. Effects of ibuprofen, diclofenac, naproxen, and piroxicam on the course of pregnancy and pregnancy outcome: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120(8):948–959. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koren G, Florescu A, Costei AM, Boskovic R, Moretti ME. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs during third trimester and the risk of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus: a meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(5):824–829. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuriya B, Hernández-Díaz S, Liu J, Bermas BL, Daniel G, Solomon DH. Patterns of medication use during pregnancy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(5):721–728. doi: 10.1002/acr.20422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gur C, Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Arnon J, Ornoy A. Pregnancy outcome after first trimester exposure to corticosteroids: a prospective controlled study. Reprod Toxicol. 2004;18(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park-Wyllie L, Mazzotta P, Pastuszak A, et al. Birth defects after maternal exposure to corticosteroids: prospective cohort study and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Teratology. 2000;62(6):385–392. doi: 10.1002/1096-9926(200012)62:6<385::AID-TERA5>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schardein JL. Chemically Induced Birth Defects. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Methotrexate [package insert] 2011. [Accessed June 26, 2015]. Available from: http://www.pfizer.ca/sites/g/files/g10017036/f/201410/Methotrexate_0.pdf.

- 39.Martin MC, Barbero P, Groisman B, Aguirre MA, Koren G. Methotrexate embryopathy after exposure to low weekly doses in early pregnancy. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;43:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buckley LM, Bullaboy CA, Leichtman L, Marquez M. Multiple congenital anomalies associated with weekly low-dose methotrexate treatment of the mother. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(5):971–973. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber-Schoendorfer C, Chambers C, Wacker E, et al. Pregnancy outcome after methotrexate treatment for rheumatic disease prior to or during early pregnancy: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(5):1101–1110. doi: 10.1002/art.38368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez Lopez JA, Loza E, Carmona L. Systematic review on the safety of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis regarding the reproductive system (fertility, pregnancy, and breastfeeding) Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(4):678–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diav-Citrin O, Blyakhman S, Shechtman S, Ornoy A. Pregnancy outcome following in utero exposure to hydroxychloroquine: a prospective comparative observational study. Reprod Toxicol. 2013;39:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sperber K, Hom C, Chao CP, Shapiro D, Ash J. Systematic review of hydroxychloroquine use in pregnant patients with autoimmune diseases. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2009;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levy RA, Vilela VS, Cataldo MJ, et al. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in lupus pregnancy: double-blind and placebo-controlled study. Lupus. 2001;10(6):401–404. doi: 10.1191/096120301678646137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Carolis S, Botta A, Salvi S, et al. Is there any role for the hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in refractory obstetrical antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) treatment? Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(9):760–762. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hydroxychloroquine [package insert] 2012. [Accessed August 15, 2015]. Available from: http://products.sanofi.ca/en/plaquenil.pdf.

- 48.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. Pregnancy outcome in women with inflammatory bowel disease following exposure to 5-aminosalicylic acid drugs: a meta-analysis. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25(2):271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nørgård B, Pedersen L, Christensen LA, Sørensen HT. Therapeutic drug use in women with Crohn’s disease and birth outcomes: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(7):1406–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bokström H, Holst RM, Hafström O, et al. Fetal hemolytic anemia associated with maternal sulfasalazine therapy during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(1):118–121. doi: 10.1080/00016340500334810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levi S, Liberman M, Levi AJ, Bjarnason I. Reversible congenital neutropenia associated with maternal sulphasalazine therapy. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;148(2):174–175. doi: 10.1007/BF00445938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sulfasalazine [package insert] 2014. [Accessed June 26, 2015]. Available from: http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=524.

- 53.Leflunomide [package insert] 2014. [Accessed June 26, 2015]. Available from: http://products.sanofi.us/arava/arava.html.

- 54.Chambers CD, Johnson DL, Robinson LK, et al. Birth outcomes in women who have taken leflunomide during pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(5):1494–1503. doi: 10.1002/art.27358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cassina M, Johnson DL, Robinson LK, et al. Pregnancy outcome in women exposed to leflunomide before or during pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(7):2085–2094. doi: 10.1002/art.34419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azathioprine [package insert] 2011. [Accessed June 12, 2015]. Available from: http://www.tritonpharma.ca/uploads/files/pdf/imuran-tablet-en.pdf.

- 57.Mozaffari S, Abdolghaffari AH, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Pregnancy outcomes in women with inflammatory bowel disease following exposure to thiopurines and antitumor necrosis factor drugs: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2015;34(5):445–459. doi: 10.1177/0960327114550882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibition and VATER association: a causal relationship. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(5):1014–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca LR, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. A safety assessment of tumor necrosis factor antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(3):635–641. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verstappen SM, King Y, Watson KD, Symmons DP, Hyrich KL. Anti-TNF therapies and pregnancy: outcome of 130 pregnancies in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):823–826. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.140822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diav-Citrin O, Otcheretianski-Volodarsky A, Shechtman S, Ornoy A. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to TNF-alpha-inhibitors: a prospective, comparative, observational study. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;43:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mahadevan U, Martin CF, Sandler RS, et al. PIANO: a 1000 patient prospective registry of pregnancy outcomes in women with IBD exposed to immunomodulators and biologic therapy. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:S149. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weber-Schoendorfer C, Oppermann M, Wacker E, et al. Pregnancy outcome after TNF-alpha inhibitor therapy during the first trimester: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(4):727–739. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katz JA, Antoni C, Keenan GF, Smith DE, Jacobs SJ, Lichtenstein GR. Outcome of pregnancy in women receiving infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(12):2385–2392. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1409–1422. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chambers C, Johnson D, Jones KL, OTIS Collaborative Research Group Pregnancy outcome in women exposed to anti-TNF-alpha medications: the OTIS rheumatoid arthritis in pregnancy study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2004;50(9):S479. Abstract 1224. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahadevan U, Wolf DC, Dubinsky M, et al. Placental transfer of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents in pregnant patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(3):286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.011. quiz e224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S, Kiho L, Pal A, Arnold J. Case report: fatal case of disseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(5):603–605. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adalimumab [package insert] 2002. [Accessed May 15, 2015]. Available from: http://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/humira.pdf.

- 70.Certolizumab [package insert] 2013. [Accessed July 20, 2015]. Available from: http://www.cimzia.com/pdf/prescribing_information.pdf.

- 71.Etanercept [package insert] 2013. [Accessed August 1, 2015]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2003/etanimm060503LB.pdf.

- 72.Golimumab [package insert] 2014. [Accessed August 1, 2015]. Available from: http://www.simponi.com/shared/product/simponi/prescribing-information.pdf.

- 73.Infliximab [package insert] 2013. [Accessed August 2, 2015]. Available from: http://www.remicade.com/shared/product/remicade/prescribing-information.pdf.

- 74.Pham T, Bachelez H, Berthelot JM, et al. Abatacept therapy and safety management. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(Suppl 1):3–84. doi: 10.1016/S1297-319X(12)70011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kumar M, Ray L, Vemuri S, Simon TA. Pregnancy outcomes following exposure to abatacept during pregnancy. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45(3):351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abatacept [package insert] 2015. [Accessed June 29, 2015]. Available from: http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_orencia.pdf.

- 77.Rituximab [package insert] 2014. [Accessed August 2, 2015]. http://www.gene.com/download/pdf/rituxan_prescribing.pdf.

- 78.Chakravarty EF, Murray ER, Kelman A, Farmer P. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to rituximab. Blood. 2011;117(5):1499–1506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mandal PK, Dolai TK, Bagchi B, Ghosh MK, Bose S, Bhattacharyya M. B cell suppression in newborn following treatment of pregnant diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patient with rituximab containing regimen. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81(10):1092–1094. doi: 10.1007/s12098-013-1336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anakinra [package insert] 2013. [Accessed July 15, 2015]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2003/anakamg062703LB.pdf.

- 81.Chang Z, Spong CY, Jesus AA, et al. Anakinra use during pregnancy in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(11):3227–3232. doi: 10.1002/art.38811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fischer-Betz R, Specker C, Schneider M. Successful outcome of two pregnancies in patients with adult-onset Still’s disease treated with IL-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(6):1021–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Berger CT, Recher M, Steiner U, Hauser TM. A patient’s wish: anakinra in pregnancy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(11):1794–1795. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.105833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tocilizumab [package insert] 2014. [Accessed July 25, 2015]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/125276lbl.pdf.

- 85.Rubbert-Roth A, Goupille P, Moosavi S, Hou A. First experiences with pregnancies in RA patients receiving tocilizumab therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2010;62(Suppl 10):384. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tofacitinib [package insert] 2015. [Accessed August 1, 2015]. Available from: http://www.xeljanz.com/

- 87.Brent RL. Teratogen update: reproductive risks of leflunomide (Arava); a pyrimidine synthesis inhibitor: counseling women taking leflunomide before or during pregnancy and men taking leflunomide who are contemplating fathering a child. Teratology. 2001;63(2):106–112. doi: 10.1002/1096-9926(200102)63:2<106::AID-TERA1017>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barrett JH, Brennan P, Fiddler M, Silman A. Breast-feeding and postpartum relapse in women with rheumatoid and inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(5):1010–1015. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1010::AID-ANR8>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ost L, Wettrell G, Björkhem I, Rane A. Prednisolone excretion in human milk. J Pediatr. 1985;106(6):1008–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):776–789. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rigourd V, de Villepin B, Amirouche A, et al. Ibuprofen concentrations in human mature milk–first data about pharmacokinetics study in breast milk with AOR-10127 “Antalait” study. Ther Drug Monit. 2014;36(5):590–596. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.LactMed: ibuprofen [Accessed June 25, 2015]. Available from: http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/lactmed.htm.

- 93.Motta M, Tincani A, Faden D, et al. Follow-up of infants exposed to hydroxychloroquine given to mothers during pregnancy and lactation. J Perinatol. 2005;25(2):86–89. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cimaz R, Brucato A, Meregalli E, Muscará M, Sergi P. Electroretinograms of children born to mothers treated with hydroxychloroquine during pregnancy and breast-feeding: comment on the article by Costedoat-Chalumeau et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(9):3056–3057. doi: 10.1002/art.20648. author reply 3057–3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Amoura Z, Aymard G, et al. Evidence of transplacental passage of hydroxychloroquine in humans. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(4):1123–1124. doi: 10.1002/art.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Esbjörner E, Järnerot G, Wranne L. Sulphasalazine and sulphapyridine serum levels in children to mothers treated with sulphasalazine during pregnancy and lactation. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1987;76(1):137–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1987.tb10430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Branski D, Kerem E, Gross-Kieselstein E, Hurvitz H, Litt R, Abrahamov A. Bloody diarrhea--a possible complication of sulfasalazine transferred through human breast milk. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5(2):316–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Moretti ME, Verjee Z, Ito S, Koren G. Breast-feeding during maternal use of azathioprine. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(12):2269–2272. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sau A, Clarke S, Bass J, Kaiser A, Marinaki A, Nelson-Piercy C. Azathioprine and breastfeeding: is it safe? BJOG. 2007;114(4):498–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Angelberger S, Reinisch W, Messerschmidt A, et al. Long-term follow-up of babies exposed to azathioprine in utero and via breastfeeding. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(2):95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bernard N, Gouraud A, Paret N, Cottin J, Descotes J, Vial T. Azathioprine and breastfeeding: long-term follow-up. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2013;27(Suppl 1):12. Abstract 05-03. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Johns DG, Rutherford LD, Leighton PC, Vogel CL. Secretion of methotrexate into human milk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;112(7):978–980. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(72)90824-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Thorne JC, Nadarajah T, Moretti M, Ito S. Methotrexate use in a breastfeeding patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(11):2332. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.van der Woude CJ, Kolacek S, Dotan I, et al. European evidenced-based consensus on reproduction in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(5):493–510. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Vasiliauskas EA, Church JA, Silverman N, Barry M, Targan SR, Dubinsky MC. Case report: evidence for transplacental transfer of maternally administered infliximab to the newborn. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(10):1255–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kane S, Ford J, Cohen R, Wagner C. Absence of infliximab in infants and breast milk from nursing mothers receiving therapy for Crohn’s disease before and after delivery. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(7):613–616. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31817f9367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Kopylov U, et al. Detection of infliximab in breast milk of nursing mothers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):555–558. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Katz L, et al. Adalimumab level in breast milk of a nursing mother. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(5):475–476. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Murashima A, Watanabe N, Ozawa N, Saito H, Yamaguchi K. Etanercept during pregnancy and lactation in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis: drug levels in maternal serum, cord blood, breast milk and the infant’s serum. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(11):1793–1794. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.105924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Keeling S, Wolbink GJ. Measuring multiple etanercept levels in the breast milk of a nursing mother with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(7):1551. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ostensen M, Eigenmann GO. Etanercept in breast milk. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(5):1017–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wallenius M, Lie E, Daltveit AK, et al. No excess risks in offspring with paternal preconception exposure to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(1):296–301. doi: 10.1002/art.38919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sussman A, Leonard JM. Psoriasis, methotrexate, and oligospermia. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116(2):215–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Grunnet E, Nyfors A, Hansen KB. Studies of human semen in topical corticosteroid-treated and in methotrexate-treated psoriatics. Dermatologica. 1977;154(2):78–84. doi: 10.1159/000251036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Morris LF, Harrod MJ, Menter MA, Silverman AK. Methotrexate and reproduction in men: case report and recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(5 Pt 2):913–916. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Weber-Schoendorfer C, Hoeltzenbein M, Wacker E, Meister R, Schaefer C. No evidence for an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcome after paternal low-dose methotrexate: an observational cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53(4):757–763. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.O’Moráin C, Smethurst P, Doré CJ, Levi AJ. Reversible male infertility due to sulphasalazine: studies in man and rat. Gut. 1984;25(10):1078–1084. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.10.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nørgård B, Pedersen L, Jacobsen J, Rasmussen SN, Sørensen HT. The risk of congenital abnormalities in children fathered by men treated with azathioprine or mercaptopurine before conception. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19(6):679–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Teruel C, López-San Román A, Bermejo F, et al. Outcomes of pregnancies fathered by inflammatory bowel disease patients exposed to thiopurines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(9):2003–2008. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]