Abstract

Hereditary elliptocytosis (HE) and hereditary pyropoikilocytosis (HPP) are heterogeneous red blood cell (RBC) membrane disorders that result from mutations in the genes encoding α-spectrin (SPTA1), β-spectrin (SPTB), or protein 4.1R (EPB41). The resulting defects alter the horizontal cytoskeletal associations and affect RBC membrane stability and deformability causing shortened RBC survival. The clinical diagnosis of HE and HPP relies on identifying characteristic RBC morphology on peripheral blood smear and specific membrane biomechanical properties using osmotic gradient ektacytometry. However, this phenotypic diagnosis may not be readily available in patients requiring frequent transfusions, and does not predict disease course or severity. Using Next-Generation sequencing, we identified the causative genetic mutations in fifteen patients with clinically suspected HE or HPP and correlated the identified mutations with the clinical phenotype and ektacytometry profile. In addition to identifying three novel mutations, gene sequencing confirmed and, when the RBC morphology was not evaluable, identified the diagnosis. Moreover, genotypic differences justified the phenotypic differences within families with HE/HPP.

Keywords: hemolytic anemia, red blood cell membrane, elliptocytosis, pyropoikilocytosis, mutation

Introduction

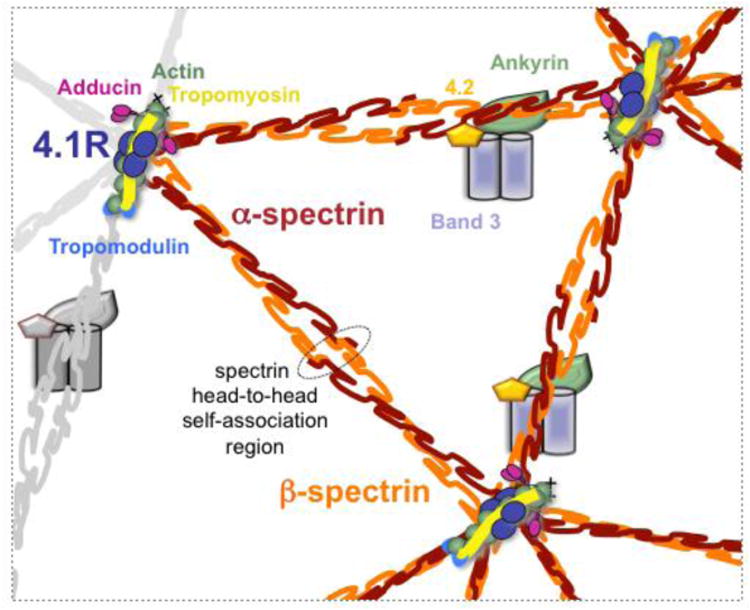

Hereditary elliptocytosis (HE) and hereditary pyropoikilocytosis (HPP) are genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous hemolytic anemias that result from mutations in the genes encoding the red blood cell (RBC) cytoskeleton proteins α-spectrin, β-spectrin, or protein 4.1R [1]. Spectrin, the primary RBC cytoskeleton protein, is composed of α-β heterodimers assembled in antiparallel fashion into flexible rods which self-associate head-to-head (each head composed by the N-terminal region of α-spectrin and the C-terminal region of β-spectrin) to form tetramers [2, 3]. Binding of the spectrin tetramer with actin at the junctional complex is mediated by protein 4.1R and is essential for RBC membrane stability (Figure 1) [4]. Defects in the spectrin-protein 4.1R-actin complex weaken the “horizontal” cytoskeletal associations causing decreased mechanical stability and deformability of erythrocytes [5]. HE/HPP disease is caused by mutations in SPTA1 and SPTB genes, causing qualitative defects of α- and β-spectrin respectively, and in EPB41 gene causing quantitative or qualitative defects of protein 4.1R. SPTA1 and SPTB mutations can be within or near the spectrin self-association domains disrupting the stability of spectrin tetramer, or away from the spectrin head-to head self-association site, mostly affecting residues critical for interactions between spectrin helices or between spectrin and ankyrin [1].

Figure 1.

Schematic of the erythrocyte cytoskeleton highlighting the spectrin head-to-head self-association region and the protein 4.1R in the junctional complex contributing to spectrin-actin interaction.

The clinical diagnosis of HE and HPP relies on identifying abnormal RBC morphology on peripheral blood smear (elliptocytes, poikilocytosis and fragmented RBCs), and identifying characteristic membrane biomechanical properties using osmotic gradient ektacytometry. Ektacytometry is an objective reference technique that can aid in the diagnosis of RBC membrane disorders [6]. In ektacytometry, the deformability of the patient's RBCs is assessed based on their laser diffraction pattern while they are subjected to a defined value of shear stress and an increasing osmotic gradient [7, 8]. The resulting ektacytometry curve reflects biomechanical properties of the RBCs including osmotic fragility, surface-to-volume ratio, cytoskeleton flexibility, and cytoplasmic viscosity. The typical HE ektacytometry curve is trapezoidal with decreased RBC deformability, while a larger decrease in deformability is noted in HPP (Figures 2 and 3) [4, 8].

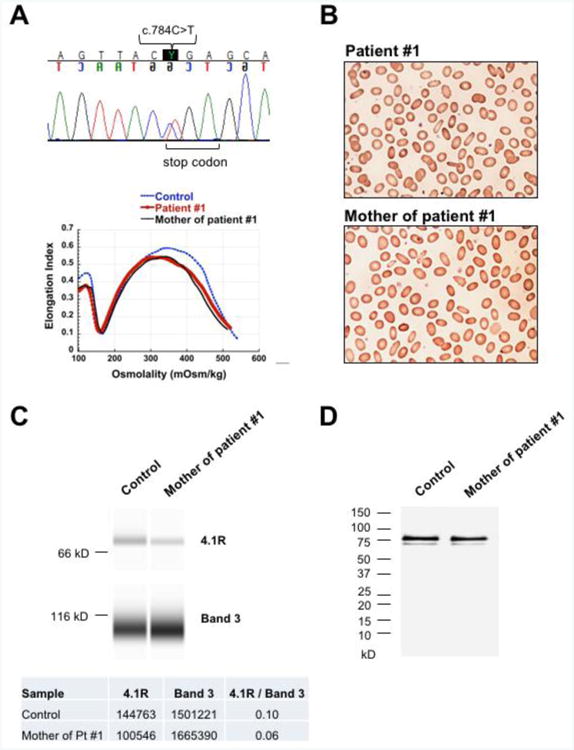

Figure 2. Novel EPB41 mutation causing HE.

(A) DNA sequencing of patient #1 and his mother with HE revealed a novel heterozygous nonsense mutation C>T in nucleotide 784 of EPB41 gene. This mutation introduces a stop codon in position p.R262 causing decreased production of protein 4.1R. Ektacytometry profile of patient #1 and his mother demonstrating trapezoidal curve with the maximum value of deformability or elongation index (EImax) decreased and shifted to the left, characteristic for HE. (B) Blood smears of patient #1 and his mother demonstrating multiple elliptocytes consistent with the diagnosis of HE. (C) Immunodetection by capillary electrophoresis of protein 4.1R versus band 3 in RBC ghost membrane of the mother of patient #1 compared to normal control. Densitometry of the bands demonstrates a decrease of 4.1R in this case of HE by 40%. (D) Immunoblotting after SDS-PAGE electrophoresis of RBC ghosts of the mother of patient #1 demonstrating normal protein 4.1R with its subcomponents 4.1a and 4.1b compared to normal controls. No truncated forms of protein 4.1R were detected (molecular weight ladder is shown on the left).

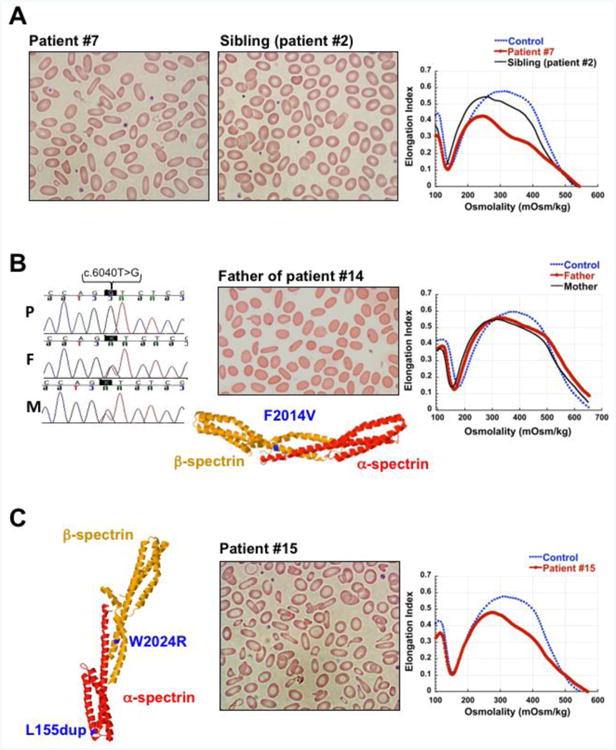

Figure 3. Biallelic spectrin mutations causing HPP.

(A) HPP due to SPTA1 mutation in trans to αLELY. Blood smears and ektacytometry profiles of patient #7 with HPP due to p.L154_L155insL mutation in SPTA1 gene in trans to αLELY allele and her sibling (patient #2) with HE, heterozygous for the same HE-causing mutation, p.L154_L155insL, in trans to a normal SPTA1 allele. Blood smear demonstrates increased poikilocytosis and elliptocytosis and ektacytometry indicates worsened deformability in the patient carrying αLELY compared to her sibling. (B) HPP due to novel homozygous SPTB mutation. DNA sequencing revealed a homozygous SPTB missense mutation (c.6040T>G, p.F2014V) in patient # 14 with HPP (P); both father (F) and mother (M) were found heterozygous for the same mutation. 3-D structure of the erythrocyte α- and β-spectrin tetramerization domain complex showing the position of the novel p.F2014V mutation (in blue) in relation to the spectrin self-association site. A mutation at this position likely affects the α-β spectrin interaction causing HE in heterozygous state and HPP in the homozygous state. Blood smear of the father shows elliptocytosis, and ektacytometry profiles of both parents demonstrate RBC deformability consistent with mild HE. Ektacytometry was not performed in the child since he was chronically transfused. (C) HPP due to compound SPTA1 and SPTB mutations. 3-D structure of the erythrocyte spectrin tetramerization domain complex showing (in blue) the positions of the mutations p.W2024R in β-spectrin (within the spectrin self-association site) and p.L154_L155insL in α-spectrin (near the spectrin self-association site) in patient # 15. Blood smear and ektacytometry profile of patient # 15 consistent with HPP. The 3-D structures were depicted in Jmol (an open-source Java viewer for chemical structures in 3D (http://www.jmol.org/), using the protein data bank (PDB) file 3lbx (DOI: 10.2210/pdb3lbx/pdb).

Clinical diagnosis of HE/HPP using blood smear examination and ektacytometry requires a pure RBC population, which may not be available in patients requiring frequent transfusions and does not predict disease course or severity. In this study we identified the causative genetic mutations in 15 patients with HE or HPP using Next-Generation sequencing, and correlated the identified mutations with phenotype and ektacytometric RBC properties. Three of these mutations (one each in EPB41, SPTA1, and SPTB) were novel. Gene sequencing confirmed and, when the RBC morphology was not evaluable, identified the diagnosis. Moreover, genotypic differences justified the differences in phenotype seen within families with HE/HPP.

Materials and Methods

Fifteen patients, from 13 different families, with clinically suspected HE or HPP (6 with HE and 9 with HPP) underwent evaluation at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center under an Institutional Review Board-approved research protocol. A Next-Generation sequencing panel of 12 genes associated with RBC membrane disorders (ABCG5, ABCG8, ANK1, EPB41, EPB42, PIEZO1, RHAG, SLC2A1 [GLUT1], SLC4A1, SPTA1, SPTB, XK) was used to evaluate for the presence of genetic mutations, which were then confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The identified genetic mutations were correlated with clinical data, peripheral blood smears, and ektacytometry results for each patient.

For ektacytometry, 250 μL of whole blood was analyzed within 24 hours of sample collection (with the exception of the case in Figure 3B, where ektacytometry was performed at 48 hours after sample collection) using LoRRca®MaxSis osmoscan (Mechatronics USA LLC, Warwick, RI). The samples were collected in vials with EDTA as anticoagulant and at the same time a similar specimen from a healthy volunteer was also drawn as a control. Control and patients' specimens were kept or shipped at 4°C until the time of analysis. Patients' RBCs deformation was monitored while exposed to a constant shear stress of 30 Pa and an increasing osmotic gradient in order to generate the ektacytometry curves.

For RBC cytoskeleton membrane protein detection: RBC membrane ghosts were prepared by hypotonic lysis [9]. Cytoskeletal proteins were evaluated by immunodetection using a size-based capillary electrophoresis instrument Wes (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA) or by standard SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting and detection using the infrared imager Odyssey (LI-COR Biotechology, Lincoln, NE).

Results and Discussion

All 15 patients were found to have mutations in SPTA1, SPTB or EPB41 (Table 1). Ten patients had mutations in SPTA1 only, one in SPTB, one was compound heterozygous for mutations affecting both α- and β-spectrin and one had a mutation in EPB41. Most patients (10/15) had mutations within or near the spectrin self-association site.

Table 1. Genetic Mutations and The Associated Diagnosis in HE and HPP Patients.

| Dx | Patient | Genes | Nucleotide variation | Type | Effect | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HE (heterozygous mutations) | 1 | EPB41 allele 1 | c.784C>T | Nonsense | p.R262* | Novel |

| 2* | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.460_463insTTG | Duplication | p.L154_L155insL | ||

| 3 | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.460_463insTTG | Duplication | p.L154_L155insL | ||

| 4 | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.460_463insTTG | Duplication | p.L154_L155insL | ||

| 5 | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.2373C>A | Missense | p.D791E | Jendouba | |

| 6 | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.2373C>A | Missense | p.D791E | Jendouba | |

| HPP due to SPTA1 HE-mutation in trans to αLELY polymorphism (c.6531-12C>T and c.5572C>G, p.L1858V) | 7* | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.460_463insTTG | Duplication | p.L154_L155insL | |

| SPTA1 allele 2 | αLELY | |||||

| 8§ | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.82C>A | Missense | p.R28S | ||

| SPTA1 allele 2 | αLELY | |||||

| 9§ | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.82C>A | Missense | p.R28S | ||

| SPTA1 allele 2 | αLELY | |||||

| 10 | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.460_463insTTG | Duplication | p.L154_L155insL | ||

| SPTA1 allele 2 | αLELY | |||||

| 11 | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.83G>A | Missense | p.R28H | Corbeil | |

| SPTA1 allele 2 | αLELY | |||||

| 12 | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.1406_1408delATC | Deletion | p.H469del | Alexandria | |

| SPTA1 allele 2 | αLELY | |||||

| 13 | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.6421C>T | Missense | p.R2141W | Novel | |

| SPTA1 allele 2 | αLELY | |||||

| HPP due to two HE-mutations in two separate alleles | 14 | SPTB allele 1 | c.6040T>G | Missense | p.F2014V | Novel (homozygous) |

| SPTB allele 2 | c.6040T>G | Missense | p.F2014V | |||

| 15 | SPTA1 allele 1 | c.460_463insTTG | Duplication | p.L154_L155insL | ||

| SPTB allele 1 | c.6070T>A | Missense | p.W2024R | Linguere |

Dx: diagnosis; HE: hereditary elliptocytosis; HPP: hereditary pyropoikilocytosis

The 15 patients listed above are from 13 different families.

patients #2 and #7 are siblings

patients #8 and #9 are siblings

HE is caused by monoallelic (heterozygous) mutations while HPP, the more severe form, is typically caused by biallelic (homozygous or compound heterozygous) mutations [4]. Of the 6 HE patients in our cohort, one was heterozygous for a novel mutation in EPB41 and five were heterozygous for mutations in SPTA1. Patient # 1 (Figure 2) was a 12-month-old Caucasian boy who had presented with mild hemolytic anemia at 4 months of age, but did not require any transfusion (Table 2). Elliptocytes were noted on blood smear and HE was suspected. DNA sequencing revealed that he was heterozygous for a novel nonsense mutation in the EPB41 gene: a C>T nucleotide change resulting in a premature stop codon in position p.R262. The same mutation was found in the mother. Ektacytometry and blood smear confirmed the similarity of phenotype between the patient and his mother, who was diagnosed with HE after her son's diagnosis. This mutation is expected to cause decreased production of band 4.1R leading to defective horizontal interaction between spectrin and actin in the RBC cytoskeleton and manifesting as autosomal dominant HE [10]. We found a decrease in protein 4.1R by up to 40% in the patient's mother RBC membrane ghosts compared to normal controls (Figure 2C), consistent with previous studies [10, 11] that showed a 15-30% decrease in 4.1R levels in patients with heterozygous nonsense EPB41 mutations. No truncated forms of protein 4.1R were detectable (Figure 2D). The other HE patients were heterozygous for SPTA1 mutations: three (patients # 2, 3 and 4) carried the common p.L154_L155insL mutation that affects the second repeat of α-spectrin and alters spectrin self-association [12], and two (patients # 5 and 6) were heterozygous for p.D791E mutation, also known as spectrin Jendouba, distant from the spectrin head-to-head self-association site [13]. Both patients with the missense mutation p.D791E were asymptomatic at baseline but had ektacytometry profile consistent with mild HE; one presented with neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and the second was evaluated because of hemolytic episodes occurring during acute infections.

Table 2. Laboratory Characteristics of Patients with Novel Mutations.

| Patient | RBC count (106/μL) | Hemoglobin (g/dL) | MCV (fL) | MCH (pg) | MCHC (g/dL) | RDW (%) | ARC (103/μL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient #1 | 3.9 | 9.9 | 73.3 | 25.4 | 37.4 | 17.7 | 113 |

| Patient #13 | 3.0 | 10.5 | 96.3* | 34.9 | 36.3 | 14 | 119 |

| Patient #14 | 2.2 | 4.9 | 60.2 | 22 | 36.5 | 26.3 | 187 |

RBC: red blood cell; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RDW: red blood cell distribution width; ARC: absolute reticulocyte count.

This test was done in neonatal period. Normal MCV for age: 98-118 fL.

HPP is typically diagnosed in patients with family history of HE but presents with increased severity, frequently with transfusion requirement in infancy or, rarely, long-term transfusion-dependence. Peripheral blood smears demonstrate increased poikilocytosis and RBC fragmentation compared to HE. HPP is caused by biallelic mutations; most frequently compound heterozygosity for a SPTA1 HE-causing structural mutation in trans to a low-expression SPTA1 allele. In our cohort, seven out of nine patients with HPP (patients #7-13) carried a pathogenic HE mutation in SPTA1 (p.L154_L155insL, p.R28S, p.R28H, p.H469del, or p.R2141W) in trans to αLELY (Low Expression LYon) SPTA1 allele (Table 1). αLELY is found in 20-30% of the population and consists of the mutation c.6531-12C>T in intron 45 inherited in cis to the missense variant c.5572C>G (p.L1858V) in exon 40. This polymorphism results in partial skipping of exon 46 and consequently a decrease in the amount of spectrin available for membrane assembly [14]. Because α-spectrin is produced in excess, αLELY is silent in normal individuals; however, patients who are compound heterozygous for a mutant SPTA1 allele and αLELY in trans have a relatively increased incorporation of the defective spectrin in the cytoskeleton, resulting in a more severe phenotype [15]. This known effect of αLELY on modifying the elliptocytosis phenotype within families [1] is demonstrated in patients #2 and 7 who are siblings and carry the same SPTA1 mutation (p.L154_L155insL); patient # 7 also carries αLELY in trans to the HE mutation causing more severe anemia, poikilocytosis, and worsened deformability consistent with HPP rather than HE in the sibling (patient #2) (Figure 3A). An additional example is the family of patients # 8 and 9, siblings with HPP due to compound heterozygosity for the SPTA1 self-association site mutation (p.R28S) in trans to αLELY. Their father was heterozygous for the same mutation in trans to a normal SPTA1 allele and had mild HE, diagnosed after the children were diagnosed, while their mother was carrier for αLELY only and was asymptomatic.

Patient # 13, a female infant of African origin, presented with severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and hemolytic anemia at 24 hours of life requiring phototherapy; blood transfusion was not needed. Laboratory results are shown in table 2. Blood smear was characterized by poikilocytosis with several elliptocytes while ektacytometry was suggestive of HE/HPP. She was found to have a novel missense variant in SPTA1, p.R2141W, affecting repeat 20 of α-spectrin near the C-terminus. This variant is predicted to be “probably damaging” with a score of 1.0 through the use of the mutation prediction software PolyPhen-2 [16]. Since the repeat α20 is a specialized dimerization repeat participating at the α-β-spectrin nucleation site near the junctional complex, the variant p.R2141W may disturb the assembly of spectrin heterodimers and subsequent tetramer formation [3, 17], likely leading to an HE phenotype in heterozygous state and HPP when co-inherited with αLELY in trans, as in this case.

Patient # 14 was a 3.5-year-old boy of Iranian descent who had presented with severe transfusion-dependent anemia since infancy and therefore his erythrocyte phenotype could not be evaluated (Table 2). Family history was significant for three maternal cousins who had undergone splenectomy for an uncharacterized hemolytic anemia. Next-Generation sequencing of the RBC membrane disorders genes revealed that he was homozygous for a novel missense mutation in SPTB gene c.6040T>G resulting in the substitution of a highly conserved phenylalanine in codon 2014 near the C-terminus of β-spectrin to valine (Figure 3B) [2]. Similar to other mutations involving β-spectrin at the self-association site, like p.W2024R or p.A2018G [18, 19], the novel mutation p.F2014V is expected to alter the α- and β-spectrin interaction causing HE in heterozygous state and HPP in homozygous state. Both parents were heterozygous for the same mutation and were asymptomatic, but their ektacytometry profiles and blood smears were consistent with HE (Figure 3B).

Patient #15 was found to have a mutation affecting α-spectrin (p.L154_L155insL) and a mutation affecting β-spectrin (p.W2024R) near or within the self-association site respectively (Figure 3C). Separately, each of these mutations in heterozygous state causes autosomal dominant HE [12, 19]. This infant of Mauritanian origin was compound heterozygous for both mutations and had more severe hemolysis, poikilocytosis and decreased deformability by ektacytometry consistent with HPP (Figure 3C), adding to the rare cases reported previously of patients co-inheriting α- and β-spectrin mutations as a cause of HPP [20, 21].

Conclusion

Targeted sequencing using a Next-Generation sequencing platform is an efficient approach to identify or confirm the diagnosis of HE and HPP, especially in severe, transfusion-dependent cases where the RBC phenotype cannot be evaluated. Moreover, causative molecular diagnosis allows genotype-phenotype correlations in these heterogeneous disorders and may assist in prognosis discussions. When HPP is caused by an HE-causing mutation in SPTA1 in trans to αLELY, significant poikilocytosis and possible transfusion requirement is noted in infancy, typically with improvement of the phenotype to a mild hemolytic anemia later on. Heterozygous HE-causing mutations in both SPTB and SPTA1 demonstrated a similar HPP phenotype (significant in infancy with improvement after the first few months of life) in our case of patient #15 as well as in similar cases described previously [20, 21]. In contrast, HPP due to biallelic SPTB mutations in the tetramerization domain appears to cause severe transfusion-dependent hemolytic anemia. Combining clinical data, ektacytometry, and family studies is essential in understanding the relevance of new genetic variants to the pathology of RBC cytoskeletal disorders, providing insights into the genotype-phenotype correlation, and improving the genetic counseling and clinical care for these patients and families.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the CCHMC Hematology Clinical Research Support Team and the patients and families for their participation in this study. The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number 1UL1TR001425-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- HE

hereditary elliptocytosis

- HPP

hereditary pyropoikilocytosis

- RBC

red blood cell

- Elmax

the maximum value of elongation index

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: O.N. and T.A.K. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript, O.N., S.C., M.O.A., K.K., Z.R.R., P.T.M., M.Q., and T.A.K. enrolled patients and collected clinical data, S.C., M.R., N.D., K.Z. performed research and analyzed data. All authors reviewed and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gallagher PG. Hereditary elliptocytosis: spectrin and protein 4.1R. Semin Hematol. 2004;41:142–164. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherry L, Menhart N, Fung LW. Interactions of the alpha-spectrin N-terminal region with beta-spectrin. Implications for the spectrin tetramerization reaction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2077–2084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ipsaro JJ, Harper SL, Messick TE, Marmorstein R, Mondragon A, Speicher DW. Crystal structure and functional interpretation of the erythrocyte spectrin tetramerization domain complex. Blood. 2010;115:4843–4852. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-261396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Da Costa L, Galimand J, Fenneteau O, Mohandas N. Hereditary spherocytosis, elliptocytosis, and other red cell membrane disorders. Blood Rev. 2013;27:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An X, Mohandas N. Disorders of red cell membrane. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:367–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohandas N, Gallagher PG. Red cell membrane: past, present, and future. Blood. 2008;112:3939–3948. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-161166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohandas N, Clark MR, Health BP, Rossi M, Wolfe LC, Lux SE, Shohet SB. A technique to detect reduced mechanical stability of red cell membranes: relevance to elliptocytic disorders. Blood. 1982;59:768–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Costa L, Suner L, Galimand J, Bonnel A, Pascreau T, Couque N, Fenneteau O, Mohandas N p. group of Societe d'Hematologie et d'Immunologie, d.H. Societe Francaise. Diagnostic tool for red blood cell membrane disorders: Assessment of a new generation ektacytometer. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2016;56:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett V. Proteins involved in membrane--cytoskeleton association in human erythrocytes: spectrin, ankyrin, and band 3. Methods Enzymol. 1983;96:313–324. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)96029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feddal S, Brunet G, Roda L, Chabanis S, Alloisio N, Morle L, Ducluzeau MT, Marechal J, Robert JM, Benz EJ, Jr, et al. Molecular analysis of hereditary elliptocytosis with reduced protein 4.1 in the French Northern Alps. Blood. 1991;78:2113–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalla Venezia N, Gilsanz F, Alloisio N, Ducluzeau MT, Benz EJ, Jr, Delaunay J. Homozygous 4.1(-) hereditary elliptocytosis associated with a point mutation in the downstream initiation codon of protein 4.1 gene. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1713–1717. doi: 10.1172/JCI116044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roux AF, Morle F, Guetarni D, Colonna P, Sahr K, Forget BG, Delaunay J, Godet J. Molecular basis of Sp alpha I/65 hereditary elliptocytosis in North Africa: insertion of a TTG triplet between codons 147 and 149 in the alpha-spectrin gene from five unrelated families. Blood. 1989;73:2196–2201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alloisio N, Wilmotte R, Morle L, Baklouti F, Marechal J, Ducluzeau MT, Denoroy L, Feo C, Forget BG, Kastally R, et al. Spectrin Jendouba: an alpha II/31 spectrin variant that is associated with elliptocytosis and carries a mutation distant from the dimer self-association site. Blood. 1992;80:809–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marechal J, Wilmotte R, Kanzaki A, Dhermy D, Garbarz M, Galand C, Tang TK, Yawata Y, Delaunay J. Ethnic distribution of allele alpha LELY, a low-expression allele of red-cell spectrin alpha-gene. Br J Haematol. 1995;90:553–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maillet P, Alloisio N, Morle L, Delaunay J. Spectrin mutations in hereditary elliptocytosis and hereditary spherocytosis. Hum Mutat. 1996;8:97–107. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)8:2<97::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Speicher DW, Weglarz L, DeSilva TM. Properties of human red cell spectrin heterodimer (side-to-side) assembly and identification of an essential nucleation site. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14775–14782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahr KE, Coetzer TL, Moy LS, Derick LH, Chishti AH, Jarolim P, Lorenzo F, Miraglia del Giudice E, Iolascon A, Gallanello R, et al. Spectrin cagliari. an Ala-->Gly substitution in helix 1 of beta spectrin repeat 17 that severely disrupts the structure and self-association of the erythrocyte spectrin heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22656–22662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolas G, Pedroni S, Fournier C, Gautero H, Craescu C, Dhermy D, Lecomte MC. Spectrin self-association site: characterization and study of beta-spectrin mutations associated with hereditary elliptocytosis. Biochem J. 1998;332(Pt 1):81–89. doi: 10.1042/bj3320081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhermy D, Galand C, Bournier O, King MJ, Cynober T, Roberts I, Kanyike F, Adekile A. Coinheritance of alpha-and beta-spectrin gene mutations in a case of hereditary elliptocytosis. Blood. 1998;92:4481–4482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christensen RD, Nussenzveig RH, Reading NS, Agarwal AM, Prchal JT, Yaish HM. Variations in both alpha-spectrin (SPTA1) and beta-spectrin (SPTB) in a neonate with prolonged jaundice in a family where nine individuals had hereditary elliptocytosis. Neonatology. 2014;105:1–4. doi: 10.1159/000354884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]