Abstract

Aim: Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized by recurrent thrombosis and/or gestational morbidity in patients with antiphospholipid autoantibodies (aPL). Over recent years, IgA anti-beta2-glycoprotein I (B2GPI) antibodies (IgA aB2GPI) have reached similar clinical relevance as IgG or IgM isotypes. We recently described the presence of immune complexes of IgA bounded to B2GPI (B2A-CIC) in the blood of patients with antecedents of APS symptomalology. However, B2A-CIC's clinical associations with thrombotic events (TEV) have not been described yet.

Methods: A total of 145 individuals who were isolate positive for IgA aB2GPI were studied: 50 controls without any APS antecedent, 22 patients with recent TEV (Group-1), and 73 patients with antecedents of old TEV (Group-2).

Results: Mean B2A-CIC levels and prevalence in Group-1 were 29.6 ± 4.1 AU and 81.8%, respectively, and were significantly higher than those of Group-2 and controls (p < 0.001). In a multivariable analysis, positivity of B2A-CIC was an independent variable for acute thrombosis with a 22.7 odd ratio (confidence interval 5.1 –101.6, 95%, p < 0.001). Levels of B2A-CIC dropped significantly two months after the TEV. B2A-CIC positive patients had lower platelet levels than B2A-CIC-negative patients (p < 0.001) and more prevalence of thrombocytopenia (p < 0.019). Group-1 had no significant differences in C3 and C4 levels compared with other groups.

Conclusion: B2A-CIC is strongly associated with acute TEV. Patients who did not develop thrombosis and were B2A-CIC positive had lower platelet levels, which suggest a hypercoagulable state. This mechanism is unrelated to complement-fixing aPL. B2A-CIC could potentially select IgA aB2GPI-positive patients at risk of developing a thrombotic event.

Keywords: Immunocomplex, Immune complex, Autoimmunity, Autoantibodies, Antiphospholipid syndrome, Seronegative antiphospholipid syndrome, APL, B2GPI, Cardiolipin, IgA

Introduction

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), also known as Hughes syndrome, is a multisystemic autoimmune disorder characterized by recurrent thrombosis and/or gestational morbidity and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL)1).

Diagnosis of APS is based on strict guidelines and requires clinical and laboratory criteria. Thrombotic events in patients with APS may be arterial, venous, or small vessel thrombosis of any organ, which must be diagnosed by objective methods such as imaging techniques or histopathology1). Gestational morbidity includes unexplained spontaneous abortions or deaths of a normal fetus and premature births due to eclampsia and pre-eclampsia of placental insufficiency2, 3). There are three different APS disease entities: primary (P-APS, without other concurrent morbidity), secondary to a pre-existing systemic autoimmune disease (S-APS), and catastrophic, consisting of multiple organ thrombosis with simultaneous multi-organ failure and a mortality rate close to 50%4).

The aPL are a heterogeneous antibody group that can be directed against phospholipids, phospholipids – plasma proteins complexes or, mainly, phospholipid binding proteins. Antigens recognized by aPL can be located in plasma or associated with anionic phospholipids on plasma membranes of endothelial cells, platelets and other cells related with the coagulation system5, 6). International consensus accepted aPL for APS diagnosis are lupus anticoagulant (LA), anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL) of IgG and IgM isotypes, and anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I antibodies (aB2GPI) of IgG and IgM isotypes2, 5).

Although anti-B2GPI antibodies of IgA isotype are not included in the laboratory criteria for APS defined in 2004 due to controversial results2), in the same meeting researchers were encouraged to clarify its role in the APS6). In the last few years, the clinical relevance of IgA aB2GPI has increased7, 8) and at the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies (2010, Galveston, TX), the task force recommended testing for IgA aB2GPI in cases negative for IgG and IgM where APS is still suspected9). This determination has allowed for great diagnostic utility in patients with APS symptomatology negative for consensus aPL (APS-like patients)9), lupus erythematosus10), thrombosis in chronic kidney disease11, 12), or early graft loss of transplanted kidneys13).

While most of the antibodies detected in autoimmune diseases are not the direct cause of disease, aPL of IgG, IgM14), and IgA8) isotype are directly pathogenic. However, the presence of aPL is necessary, but not sufficient, to produce an APS event, so an additional trigger is needed to develop thrombosis15). The predictive value of the presence of aPL in developing thrombosis in a patient is low, and there are few prospective studies in APS. A 10 year follow-up multicenter prospective study of 1000 APS patients was conducted, and about 15% of patients developed a thrombotic event in the first 5 years. The study concluded that it was necessary to search for new markers to prevent the complications of APS, since even though the patients were under treatment, some of them continued to develop thrombosis16). For patients positive for IgA aB2GPI only, prospective studies were conducted in patients in hemodialysis11, 17) and in renal transplant patients13). However, only a minority of patients developed thrombotic events-- 12% in renal transplant patients during the first year13) and approximately 50% in patients on dialysis within two years11, 17). Therefore, new biomarkers are needed to identify which patients have a higher risk of thrombosis16, 18).

The presence of circulating immune complexes (CIC) of B2GPI and antibodies (IgG and IgM) in APS patients has been reported19) although they were not associated with the occurrence of thrombotic events20). We recently described a new method to detect specific CIC of IgA bounded to B2GPI (B2A-CIC) demonstrating its presence in patients positive only for IgA aB2GPI antibodies21). In the present study, we show for the first time that the presence of B2A-CIC identifies a subgroup of patients prone to develop thrombosis.

Patients and Methods

Study Design.

A cross-sectional study conducted to determine the presence of IgA-B2GPI immune complexes and their association with recent and older thrombotic events in patients positive only for IgA anti-B2GPI (negative for other aPL).

A prospective study of B2A-CIC short-term evolution in patients with recent thrombotic events.

The study complies with the Spanish legislation and European Community directives.

Patients

All patients positive only for IgA aB2GPI and negative for other aPL: aCL, IgG, IgA or IgM, and aB2GPI, IgG or IgM were recruited during one year (ending on November 30, 2014) from those referred by their physicians for aPL study to the Hospital 12 de Octubre Immunology Department. These patients were separated in two groups:

Group-1. Twenty-two patients positive for IgA aB2GPI-ab with recent thrombotic events consistent with APS clinical characteristics (supplementary Table 1) in the 30 days before aPL determination. Sera were evaluated for presence of aPL immediately after the event (mean 9.8 ± 2.2 days). All the serum samples were evaluated in the first month.

Supplementary Table 1. Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) clinical inclusion criteria.

| APS Clinical criteria | Group-1 (n = 22) | Group-2 (n = 73) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venous thrombosis | 17 | 77.3% | 65 | 89.0% |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 7 | 31.8% | 31 | 42.5% |

| Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism | 2 | 9.1% | 19 | 26.0% |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 2 | 9.1% | 3 | 4.1% |

| Portal vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism | 1 | 4.5% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Pulmonary embolism | 5 | 22.7% | 13 | 17.8% |

| Arterial thrombosis | 5 | 22.7% | 8 | 11.0% |

| Mesenteric thrombosis | 1 | 4.5% | 2 | 2.7% |

| Pulmonary thrombosis | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.4% |

| Central artery of the retina | 1 | 4.5% | 1 | 1.4% |

| Carotid thrombosis | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.4% |

| Cerebral thrombosis | 2 | 9.1% | 2 | 2.7% |

| Coronary thrombosis | 1 | 4.5% | 1 | 1.4% |

The mean age was 68.5 ± 2.4 years; 11 (50%) were male. One patient (4.5%) had an autoimmune disease and is consistent with secondary APS (S-APS). The rest of the patients were patients consistent with a diagnosis of primary APS (P-APS). Clinical characteristics are described on Table 1. 21 (95.4%) were Caucasians and 1 (4.6%) was east-African.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients on Group-1 and control group.

| Control Group (n = 50) |

Group 1 (n = 22) |

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/n | SE/ % | Mean/n | SE/ % | ||

| Age (y) | 59.1 | ±2.3 | 68.5 | ±2.4 | 0.006 |

| Sex (m) | 10 | 20.0% | 11 | 50.0% | 0.020 |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 12 | 24.0% | 7 | 31.8% | n.s. |

| Arterial hypertension (controlled) | 20 | 40.0% | 11 | 50.0% | n.s. |

| Dyslipidemia | 11 | 22.0% | 7 | 31.8% | n.s. |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | n.s. |

| No autoimmune underlying pathologies | 32 | 64.0% | 21 | 95.5% | 0.007 |

| Underlying autoimmune pathologies | 18 | 36.0% | 1 | 4.5% | 0.007 |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 13 | 26.0% | 1 | 4.5% | n.s. |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4 | 8.0% | 0 | 0.0% | n.s. |

| Systemic Sclerosis | 1 | 2.0% | 0 | 0.0% | n.s. |

SE: standard error of the mean.

Group-2. Seventy-three patients positive for IgA aB2GPI-ab with old thrombosis. Thrombotic events (supplementary Table 1) must have happened more than six months before the date of blood extraction (mean 782 ± 105 days). Eight patients (8.2%) had an autoimmune disease and are consistent with secondary APS (S-APS). The rest of patients were patients consistent with a diagnosis of primary APS (P-APS). The mean age was 59.1 ± 2.3 years; 40 (54.8%) were male. 70 (95.9%) were Caucasians and 3 (4.1%) were east-African.

Pretreatment: There were no significant differences among patients receiving treatment with immunomodulators, anticoagulants, antiplatelet or antimalarial treatment.

Asymptomatic Control Group (Control group). 50 patients positive only for IgA aB2PPI without APS-symptomatology (any thrombotic or APS-related obstetric antecedents) were recruited. The mean age was 59.1 ± 2.3 years; 10 (20%) were male. All patients were confirmed positive and remained free of thrombotic events from the time of diagnosis. The mean of time free of thrombosis from diagnosis of the presence of autoantibodies was 56.1 ± 4.5 months and the number of determinations of IgA aB2GPI that were made during the follow up period was 7.8 ± 1.4. All of the determinations were positive. Clinical characteristics are described on Table 1.

Patients with prothrombotic conditions secondary to other factors such as sepsis, homocystinemia, and genetic defects of coagulation factors (thrombin mutations, factor V Leiden, antithrombin deficiency, etc.) were not included. Data of the patients and controls were collected in an anonymized database.

Definitions

Thrombotic events: Venous and arterial thrombosis diagnosed following Sydney consensus of APS criteria2).

Current-thrombosis (CT): Thrombotic event that occurred within the 30 days prior to blood collection.

Old-thrombosis (OT): When previous thrombosis occurred from 1 to 36 months before blood collection.

Thrombocytopenia: platelets levels below 140× 103/uL

Laboratory determinations. aCL and aBGPI antibodies (IgG and IgM) were measured using the BioPLex 2200 multiplex immunoassay system (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA, USA). Antibody levels higher than 18 U/mL were considered positive following the manufacturer's guidelines.

IgA aCL and aB2GPI antibodies were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) using IgA-aCL and IgA-aB2GPI QUANTA Lite (INOVA Diagnostics Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Antibody levels higher than 20 U/mL were considered positive following the manufacturer's guidelines and the 99th percentile of a healthy population in our hospital7).

Complement factors C3 and C4 levels were measured using Beckman Coulter IMMAGE Immunochemistry System (Beckman Coulter Inc. Pasadena, CA, USA).

Quantification of B2A-CIC levels was performed as previously described21). Sera with values of B2A-CIC higher than 21 AU were considered positive. All the procedures were performed in a Triturus® Analyzer (Diagnostics Grifols, S.A., Barcelona, Spain).

Lupus Anticoagulant

Lupus anticoagulant (LA) is not routinely performed in all patients with a first thrombotic event. They are only done in special coagulation studies in patients with repeated thrombosis or elevated thrombotic risk. In patients who have a first thrombosis, LA is only ordered when the hematologist considers it is appropriate due to clinical characteristics. LA activity was detected by coagulation assays following the guidelines of the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH)22). We used the HemosIL dRVVT Screen, HemosIL dRVVT Confirm and HemosIL Silica Clotting Time assays (Instrumentation Laboratory SpA, Milano, Italy).

Statistical Methods

Results were expressed as mean ± standard error or absolute frequency and percentage. In scaled variables with two categories, comparisons were performed using the Student's t-test. Association between qualitative variables was determined with Pearson's Chi-square test incorporating Yates Continuity Correction. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

A box-and-whisker plot represents the values from the lower to upper quartile (25 to 75 percentile) in the central box. The median is represented as the middle line into the box. Data were processed and analyzed using Medcalc for Windows version 15.4 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

Results

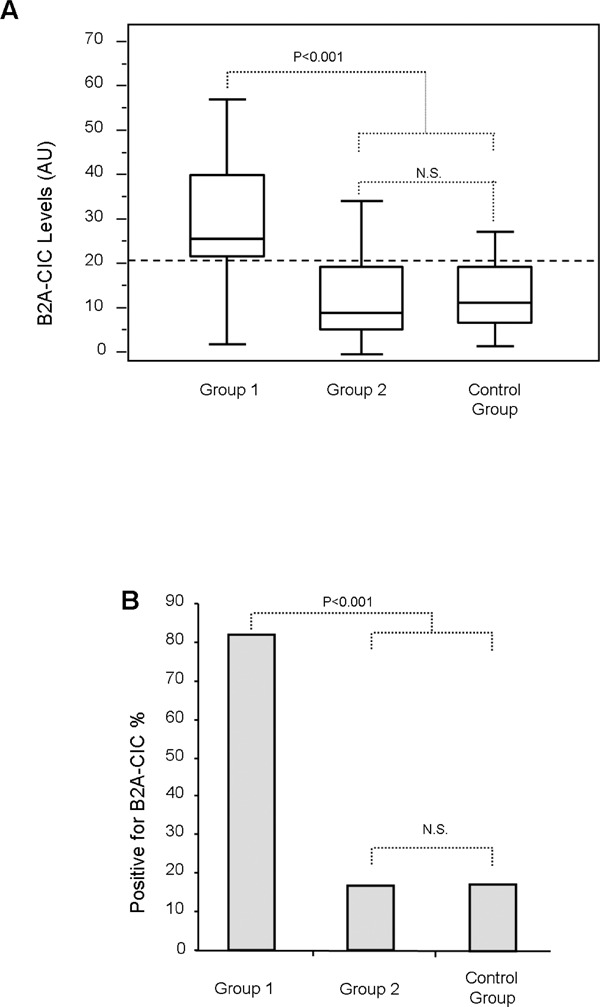

Presence of B2A-CIC

No significant differences in aB2GPI and aCL antibodies levels (IgG, IgM and IgA) between Group1, Group-2 and control patients were observed (Supplementary Table 2). Levels of B2A-CIC were significantly higher in Group-1 (29.6 ± 4.1 AU) than in the control group (15.1 ± 1.9 AU; p = 0.003; Fig. 1A). 81.8% of patients in Group-1 (18/22) were positive for B2A-CIC. This percentage was significantly higher (p < 0.001) than the 18% (9/50) observed in the control group of patients positive for IgA aB2GPI and without any thrombotic antecedent (Fig. 1B).

Supplementary Table 2. Antiphospholipid antibodies levels (IU/ml) in the three groups.

| Group-1 |

Group-2 |

Control group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | mean | SE | |

| aCL IgG | 4.7 | 1.4 | 5.6 | 1.8 | 3.1 | 0.4 |

| aCL IgM | 4.3 | 0.9 | 4.6 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 0.8 |

| aCL IgA | 4.2 | 0.5 | 4.1 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 0.3 |

| aB2GPI IgG | 4.7 | 1.5 | 5.7 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 0.6 |

| aB2GPI IgM | 2.7 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 0.7 |

| aB2GPI IgA | 66.1 | 5.8 | 68.8 | 7.2 | 68.2 | 7.7 |

SE: standard error of the mean. aCL: Anti-cardiolipin. aB2GPI: anti-Beta 2 Glycoprotein I.

Fig. 1.

Levels (A) of immune complexes of IgA bounded to B2GPI (B2A-CIC) and percentage of positives (B) in Group-1 and controls. Dotted line is the cutoff.

Prospective Study

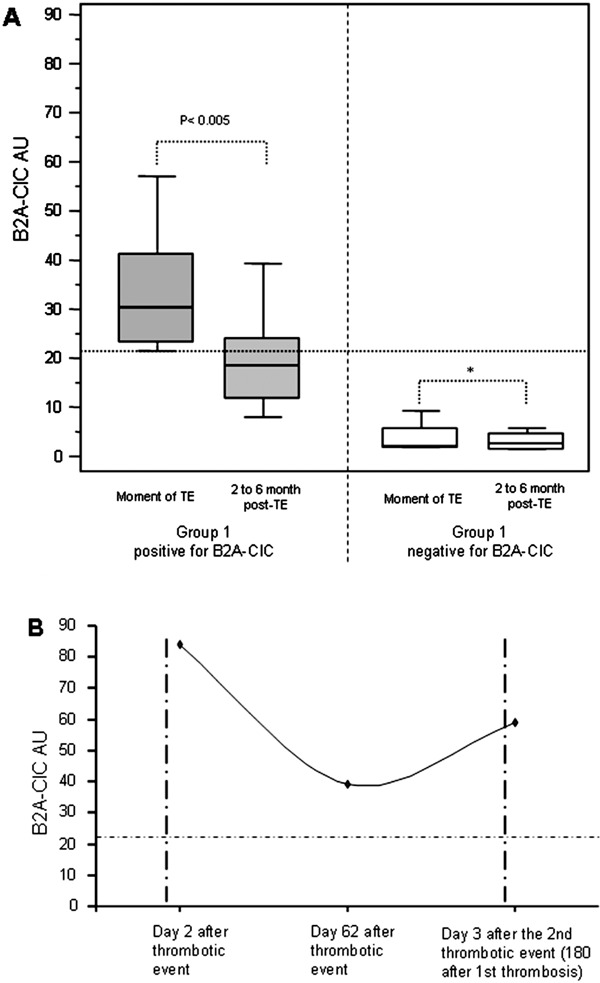

Group-1 patients were followed-up. Twenty patients were reevaluated to quantify B2A-CIC between the second and sixth month post-thrombotic event (four of them were reevaluated a second time in this period). Two patients were unavailable because they did not attend the scheduled follow-up visit. IgA aB2GPI mean levels at the moment of thrombosis did not differ from the levels in the scheduled follow-up visit and all of them were positive (data not shown). In the 20 patients who completed the follow-up, B2A-CIC levels decreased after the thrombotic event (Fig. 2A): mean B2A-CIC at the time of thrombosis was 35.3 ± 3.8 AU and in the reevaluation, it was 20.3 ± 2.7 AU (p = 0.002). The percentage of B2A-CIC positive patients two months after the thrombotic event was 35.0% (7/20), similar to the control group (p = 0.224). In the four patients in Group-1 who were negative for B2A-CIC in the first sample (mean 3.8 ± 1.8 AU), significant differences were not observed in the second sample at the time of the follow-up visit (mean 3.1 ± 1.0 AU).

Fig. 2.

Evolution of immune complexes of IgA bounded to B2GPI (B2A-CIC) levels in patients with current thrombosis (Group-1) positive and negative for B2A-CIC (A) and a case example of a Group-1 patient positive for B2A-CIC who redeveloped a thrombotic event (B). The horizontal dotted line shows the cutoff. The vertical dotted line shows the moment of thrombosis

* = non-significant.

A case example of evolution of B2A-CIC in a patient in Group-1 who had a second thrombotic event is shown in Fig. 2B. The patient had suffered a portal vein thrombosis and had elevated levels of B2A-CIC the 2nd day after the thrombosis. B2A-CIC levels dropped by 50% in the 2nd month clinical reevaluation, and while the patient was asymptomatic, they were still positive for B2A-CIC. However, 180 days after the first thrombosis, the patient developed another thrombotic event (deep venous thrombosis) and levels of B2A-CIC increased by 50% compared to the 2nd month post-thrombosis. This was the only patient with recurrent thrombosis during the follow-up.

B2A-CIC in Patients with Thrombotic Antecedents

Mean levels of B2A-CIC in sera of patients on Group-2 (patients who had a thrombotic event more than 6 months before blood extraction) was 14.8 ± 1.8 AU-- significantly lower (p < 0.001) than patients on Group-1 (first sample) but without significant differences to Group-1 reevaluation samples (2–6 month after the thrombotic event) or to the control group (p = 0.143 and p = 0.908 respectively).

Group-2 and the control group showed similar percentages of B2A-CIC positive patients: 17.8% (13/73) vs 18.0% (9/50), p= 0.832. Also, Group-2 did not differ from the percentage of B2A-CIC positive patients in Group-1 reevaluation after the thrombotic event (p= 0.177).

Multivariate Study

The variables associated with patients with recent thrombosis that were significant in the univariate analysis (Table 1) were included in a multivariate analysis. The odds ratio for B2A-CIC in the multivariate study was 22.7 for recent thrombosis (p < 0.001), appearing as a risk factor for thrombosis. The odds ratio for the presence of an autoimmune disease was 0.08 OR (p = 0.046, Table 2). Sex and age were not significant.

Table 2. Multivariate analysis (p < 0.001) of factors associated with recent thrombosis.

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| B2A-CIC positive | 22.7 | 5.055 to 101.571 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.0 | 0.969 to 1.095 | 0.335 |

| Sex | 2.8 | 0.648 to 12.502 | 0.166 |

| Presence of autoimmune disease | 0.08 | 0.007 to 0.954 | 0.046 |

Area under the ROC curve: 0.915; 95% CI: 0.823 to 0.968.

Lupus Anticoagulant

52 patients were analyzed for LA according to hematologist criteria: 10 in Group-1 (all were negative) and 42 in Group-2. Six patients in Group-2 (11%) were positive and all of them were negative for B2A-CIC.

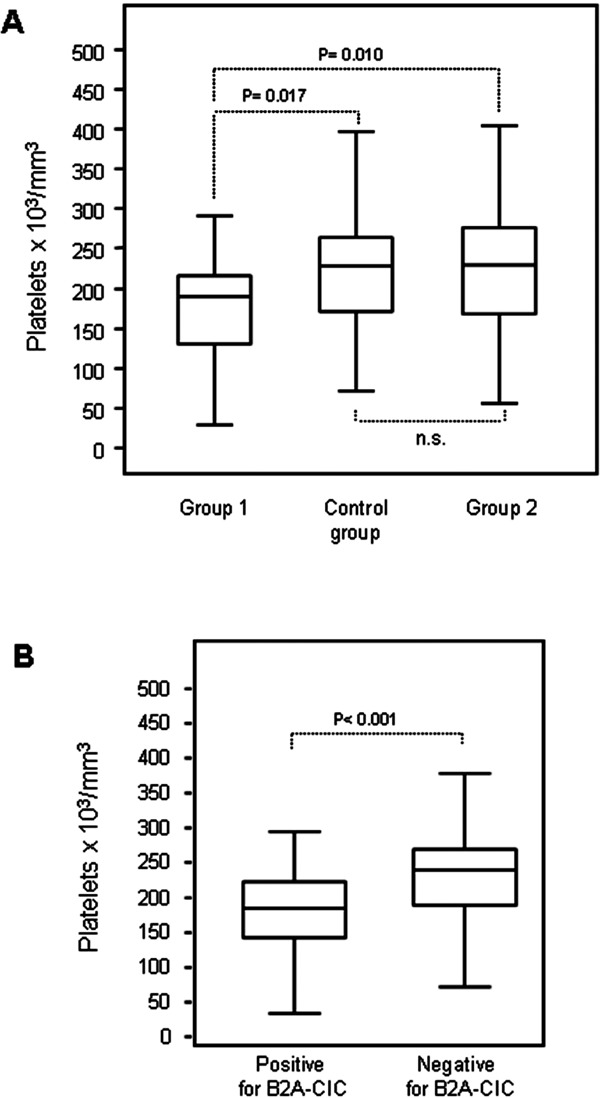

Platelet Levels

The Group-1 mean platelet levels were 182.7 ± 14.6 × 1000/uL, which was lower than those in Group-2 (229.2 ± 9.0 × 1000/uL; p = 0.010) or in the control group (225.2 ± 8.9 ± 1000/uL; p = 0.017). However, no significant differences were observed between the control group and Group-2 (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Platelet levels in the groups (A) and in positive and negative for immune complexes of IgA bounded to B2GPI (B2A-CIC) (B).

When IgA aB2GPI positive patients were analyzed according to whether they were B2A-CIC positive or negative, independently of whether they had a current or past thrombosis, or did not have thrombosis, we obtained mean platelet levels of 185.5 ± 9.4 × 1000/uL for positive B2A-CIC and 234.8 ± 6.9 × 1000/uL for negative B2A-CIC (p = 0.0001) (Fig. 3b).

In Group-1, 27.3% of patients (6/22) had thrombocytopenia. This proportion was not significantly higher (p = 0.07) than that observed in the control group, 10.0% (5/50), or in Group-2, 12.3% (9/73; p = 0.18). Nevertheless, thrombocytopenia in B2A-CIC positive patients (in all groups) was 22.5%, significantly higher (p = 0.019) than the 7.6% observed in B2A-CIC negative patients in the same groups.

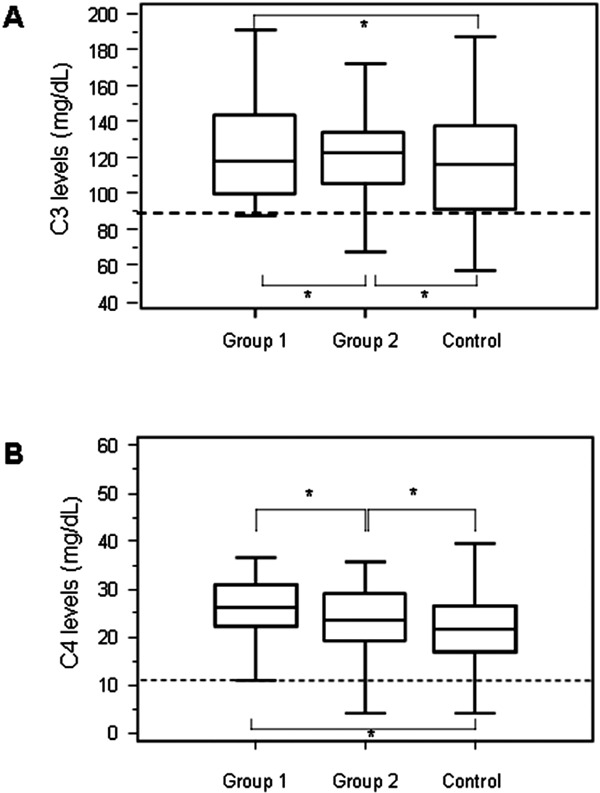

Complement Levels

Group-1 patients had 123.7 ± 7.1 mg/dl and 26.0 ± 2.5 mg/dl C3 and C4 mean levels, respectively, Group-2 patients had 121.1 ± 4.6 mg/dl and 23.7 ± 1.3 mg/dl C3 and C4 mean levels, respectively, and the control group had 113.4 ± 3.9 mg/dl and 22.8 ± 1.0 mg/dl C3 and C4 mean levels, respectively. Mean levels of Complement C3 and C4 factors in all patients groups and subgroups were within the normal range (88–252 mg/dl for C3 levels and 12–75 mg/dl for C4 levels) and were not significant. Only 1 patient with recent thrombosis had low levels of C4 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

C3 (A) and C4 (B) complement levels in groups.

* = non-significant.

Discussion

In this work, for the first time, we have described a high prevalence of B2A-CIC in patients with recent thrombosis and positive isolated for IgA aB2GPI antibodies compared with patients who presented old thrombosis and those without thrombotic antecedents. IgA aB2GPI antibodies are directly thrombogenic but the mechanisms of antibody-mediated thrombosis are unknown8). Although the presence of aB2GPI antibodies is a necessary condition, only a small group of patients positive for these antibodies develop thrombotic complications. It has been proposed that the presence of antibodies would generate a prothrombotic microenvironment. Thrombus formation would require additional prothrombotic factors (“second hit”), which are related to immune responses and are still not well known15). Therefore, as demanded in recent studies, it is necessary to search for new markers that permit the screening of patients who are really at risk of suffering a thrombotic event16).

The aCL assay is mainly for the detection of B2GPI-dependent antibodies; however, our patients presented an isolated IgA positivity for B2GPI (negative for IgA aCL). There are several studies showing that positivity for IgA aCL and IgA aB2GPI are independent7, 8, 23). The epitopes recognized by the IgA aB2GPI are mainly located in the domains 4–5 of the B2GPI protein, this region being the phospholipid binding area. When cardiolipin is incorporated to B2GPI, IgA-binding epitopes are not accessible and patients only present isolated IgA aB2GPI antibodies24, 25).

We have found that patients with acute thrombosis (Group-1) have a higher prevalence of B2A-CIC positive and higher levels of B2A-CIC than in patients with antecedents of thrombosis (Group-2) or patients in the control group. Both prevalence and levels decrease after the thrombotic event. Group-1 patients were reevaluated between two and six months after TEV showing B2A-CIC levels and positive prevalence similar to those in Group-2 and the control group.

The presence of B2A-CIC is not exclusive to patients with a history of thrombotic events. It also appears, but with lower prevalence, in asymptomatic patients. This would suggest that the presence of B2A-CIC would not be directly thrombogenic but would rather behave as an additional risk factor that favors the prothrombotic microenvironment, thus increasing the probability of occurrence of the thrombotic event.

Multivariable analysis shows positivity for B2A-CIC as an independent factor for recent thrombosis and that patients without autoimmune diseases had more thrombosis. This makes sense because of the presence of IgA aB2GPI is more frequent in patients with P-APS than in S-APS7). By performing a follow-up study on patients with recent thrombosis, we have been able to detect a drop in B2A-CIC levels two months after the thrombotic event. In spite of the small number of patients, this decrease is significant and suggests a formation of B2A-CIC during the thrombotic event.

In the analysis of platelets, we observed that the mean levels of Group-1 are lower than in the control group. This may be because they would have been consumed during the thrombotic event. Nevertheless, patients with elevated B2A-CIC levels also have significantly lower means than those in the non-elevated B2A-CIC levels. This may suggest that B2A-CIC would induce a certain degree of platelet activation/aggregation and might be able to activate platelets to produce platelet-consumption and even to produce thrombotic events in some patients. Complement activation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of aPL-induced thrombosis. Therefore, hypocomplementaemia is common in APS patients (aPL of IgG or IgM isotypes), reflecting complement activation and consumption26, 27), and blockade of the complement system has been proposed as an effective therapy for complex forms of APS28). Our finding of normal C3 and C4 levels in patients with anti-B2GPI antibodies of IgA isotype and APS-events is perfectly consistent with the results obtained because IgA does not fix complement29).

The mechanism by which the aB2GPI antibodies produce pathology is unclear. Some studies suggest that B2GPI changes its conformation after binding to the plasma membrane of platelets and endothelial cells. This would enable B2GPI antibody binding, thus producing endothelial activation30), platelet activation31) and an altered coagulation state32, 33), which could, in turn, trigger a proinflammatory and procoagulant state. The presence of the B2A-CIC could help make this activation process more effectively by increasing the probability of triggering thrombotic events in a complement-unrelated mechanism. Currently, there is no cure for APS and the treatment should be individualized and adapted to the characteristics of each patient34). The risk of thrombosis in aPL positive asymptomatic individuals is low but increases with the concurrence of other risk factors such as smoking, use of estrogens, prolonged immobilization, infections, or surgical procedures35, 36). In spite of this, at least 50% of patients who develop thrombosis do not have any other risk factor at the time when the event occurs37). Asymptomatic individuals with positive blood tests for aPL without other prothrombotic factors do not require treatment38). APS patients with thrombotic antecedents are usually treated to reduce the risk of recurrent thromboembolism34). The mainstay of the treatment is thromboprophylaxis, usually using Vitamin K antagonists. However, there is no consensus regarding the patient screening criteria and treatment duration because anticoagulant drugs are among the most common medications that cause adverse events39). Therefore, in order to select which patients should receive thromboprophylaxis, new biomarkers are needed that would make it possible to identify patients with a pro-thrombotic state and at high risk of clinical events40). B2A-CIC identification could be a new biomarker to define the population to be treated at risk of thrombotic events.

Limitations of the study: we have selected patients positive only for IgA aB2GPI and deliberately excluded seronegative and positive patients for other isotypes because they could have been a confounding factor. This makes essential the inclusion of this population in future studies. Also, our population is slightly older because although we have selected all patients with thrombosis during a year, the population of the hospital area is older, as is the population of Spain. Despite this, age was not significant in the multivariate analysis for the development of thrombosis. Another major limitation was that blood samples at the moment of thrombosis were not available.

In summary, IgA aB2GPI antibodies are, per se, a risk factor but they are not sufficient to discriminate the population potentially at risk of thrombosis. We have described for the first time an association among patients with elevated levels of B2A-CIC and acute thrombosis. Notably, B2A-CIC levels become negative 2–6 months after the thrombotic event. Furthermore, patients B2A-CIC positive present less platelet levels, suggesting a hypercoagulability state by platelet activation. This mechanism seems to be independent of complement. The study of the B2A-CIC may help us to better understand the process of a prothrombotic state prior to the development of an APS event. From a clinical point of view, if these are corroborated, it may be useful for the diagnosis of seronegative-APS and may help in the decision of whether treatment with thromboprophylaxis would be useful or not. Due to the difficulty of predicting a thrombotic event, this hypothesis needs to be confirmed in prospective studies with an elevated number of patients to determine the B2A-CIC levels pre-thrombosis in more patients and the potentially role of B2A-CIC as a predictive marker.

Acknowledgments

We thank Margarita Sevilla for her excellent technical assistance and Barbara Shapiro for her excellent work of translation and English revision of the paper.

Authors' Contribution

José Ángel Martínez-Flores and Manuel Serrano collaborated equally to this work

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias and co-financed with European Regional Development Funds. (Grants: PI12-00108, PIE13/0045 and PI14-00360).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- 1). Gomez-Puerta JA, Cervera R: Diagnosis and classification of the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Autoimmun, 2014; 48-49: 20-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, Branch DW, Brey RL, Cervera R, Derksen RH, PG DEG, Koike T, Meroni PL, Reber G, Shoenfeld Y, Tincani A, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Krilis SA: International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost, 2006; 4: 295-306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Devreese K, Hoylaerts MF: Challenges in the diagnosis of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Clin Chem, 2010; 56: 930-940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Asherson RA, Cervera R, Piette JC, Font J, Lie JT, Burcoglu A, Lim K, Munoz-Rodriguez FJ, Levy RA, Boue F, Rossert J, Ingelmo M: Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. Clinical and laboratory features of 50 patients. Medicine (Baltimore), 1998; 77: 195-207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Willis R, Harris EN, Pierangeli SS: Pathogenesis of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Semin Thromb Hemost, 2012; 38: 305-321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Branch DW: Summary of the 11th International Congress on antiphospholipid autoantibodies, Australia, November 2004. J Reprod Immunol, 2005; 66: 85-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Ruiz-Garcia R, Serrano M, Angel Martinez-Flores J, Mora S, Morillas L, Martin-Mola MA, Morales JM, Paz-Artal E, Serrano A: Isolated IgA Anti-beta 2 Glycoprotein I Antibodies in Patients with Clinical Criteria for Antiphospholipid Syndrome. J Immunol Res, 2014; 2014: 704395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Murthy V, Willis R, Romay-Penabad Z, Ruiz-Limon P, Martinez-Martinez LA, Jatwani S, Jajoria P, Seif A, Alarcon GS, Papalardo E, Liu J, Vila LM, McGwin G, Jr., McNearney TA, Maganti R, Sunkureddi P, Parekh T, Tarantino M, Akhter E, Fang H, Gonzalez EB, Binder WR, Norman GL, Shums Z, Teodorescu M, Reveille JD, Petri M, Pierangeli SS: Value of isolated IgA anti-beta2-glycoprotein I positivity in the diagnosis of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheum, 2013; 65: 3186-3193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Lakos G, Favaloro EJ, Harris EN, Meroni PL, Tincani A, Wong RC, Pierangeli SS: International consensus guidelines on anticardiolipin and anti-beta2-glycoprotein I testing: report from the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies. Arthritis Rheum, 2012; 64: 1-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcon GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, Bruce IN, Isenberg D, Wallace DJ, Nived O, Sturfelt G, Ramsey-Goldman R, Bae SC, Hanly JG, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Clarke A, Aranow C, Manzi S, Urowitz M, Gladman D, Kalunian K, Costner M, Werth VP, Zoma A, Bernatsky S, Ruiz-Irastorza G, Khamashta MA, Jacobsen S, Buyon JP, Maddison P, Dooley MA, van Vollenhoven RF, Ginzler E, Stoll T, Peschken C, Jorizzo JL, Callen JP, Lim SS, Fessler BJ, Inanc M, Kamen DL, Rahman A, Steinsson K, Franks AG, Jr., Sigler L, Hameed S, Fang H, Pham N, Brey R, Weisman MH, McGwin G, Jr., Magder LS: Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum, 2012; 64: 2677-2686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Serrano A, Garcia F, Serrano M, Ramirez E, Alfaro FJ, Lora D, de la Camara AG, Paz-Artal E, Praga M, Morales JM: IgA antibodies against beta2 glycoprotein I in hemodialysis patients are an independent risk factor for mortality. Kidney Int, 2012; 81: 1239-1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Serrano M, Martinez-Flores JA, Castro MJ, Garcia F, Lora D, Perez D, Gonzalez E, Paz-Artal E, Morales JM, Serrano A: Renal transplantation dramatically reduces IgA anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I antibodies in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Immunol Res, 2014; 2014: 641962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Morales JM, Martinez-Flores JA, Serrano M, Castro MJ, Alfaro FJ, Garcia F, Martinez MA, Andres A, Gonzalez E, Praga M, Paz-Artal E, Serrano A: Association of Early Kidney Allograft Failure with Preformed IgA Antibodies to beta2-Glycoprotein I. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2015; 26: 735-745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Giannakopoulos B, Krilis SA: The pathogenesis of the antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med, 2013; 368: 1033-1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Meroni PL, Borghi MO, Raschi E, Tedesco F: Pathogenesis of antiphospholipid syndrome: understanding the antibodies. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 2011; 7: 330-339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Cervera R, Serrano R, Pons-Estel GJ, Ceberio-Hualde L, Shoenfeld Y, de Ramon E, Buonaiuto V, Jacobsen S, Zeher MM, Tarr T, Tincani A, Taglietti M, Theodossiades G, Nomikou E, Galeazzi M, Bellisai F, Meroni PL, Derksen RH, de Groot PG, Baleva M, Mosca M, Bombardieri S, Houssiau F, Gris JC, Quere I, Hachulla E, Vasconcelos C, Fernandez-Nebro A, Haro M, Amoura Z, Miyara M, Tektonidou M, Espinosa G, Bertolaccini ML, Khamashta MA: Morbidity and mortality in the antiphospholipid syndrome during a 10-year period: a multicentre prospective study of 1000 patients. Ann Rheum Dis, 2015; 74: 1011-1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Hadhri S, Rejeb MB, Belarbia A, Achour A, Skouri H: Hemodialysis duration, Human platelet antigen HPA-3 and IgA Isotype of anti-beta2glycoprotein I antibodies are associated with native arteriovenous fistula failure in Tunisian hemodialysis patients. Thromb Res, 2013; 131: e202-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Devreese KM: Antiphospholipid antibodies: evaluation of the thrombotic risk. Thromb Res, 2012; 130 Suppl 1: S37-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Banzato A, Frasson R, Acquasaliente L, Bison E, Bracco A, Denas G, Cuffaro S, Hoxha A, Ruffatti A, Iliceto S, De Filippis V, Pengo V: Circulating beta2 glycoprotein I-IgG anti-beta2 glycoprotein I immunocomplexes in patients with definite antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus, 2012; 21: 784-786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Biasiolo A, Rampazzo P, Brocco T, Barbero F, Rosato A, Pengo V: [Anti-beta2 glycoprotein I-beta2 glycoprotein I] immune complexes in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome and other autoimmune diseases. Lupus, 1999; 8: 121-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Martinez-Flores JA, Serrano M, Perez D, Lora D, Paz-Artal E, Morales JM, Serrano A: Detection of circulating immune complexes of human IgA and beta 2 Glycoprotein I in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome symptomatology. J Immunol Methods, 2015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Brandt JT, Triplett DA, Alving B, Scharrer I: Criteria for the diagnosis of lupus anticoagulants: an update. On behalf of the Subcommittee on Lupus Anticoagulant/Antiphospholipid Antibody of the Scientific and Standardisation Committee of the ISTH. Thromb Haemost, 1995; 74: 1185-1190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Mattia E, Ruffatti A, Tonello M, Meneghel L, Robecchi B, Pittoni M, Gallo N, Salvan E, Teghil V, Punzi L, Plebani M: IgA anticardiolipin and IgA anti-beta2 glycoprotein I antibody positivity determined by fluorescence enzyme immunoassay in primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Clin Chem Lab Med, 2014; 52: 1329-1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Sweiss NJ, Bo R, Kapadia R, Manst D, Mahmood F, Adhikari T, Volkov S, Badaracco M, Smaron M, Chang A, Baron J, Levine JS: IgA anti-beta2-glycoprotein I autoantibodies are associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One, 2010; 5: e12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Andreoli L, Chighizola CB, Nalli C, Gerosa M, Borghi MO, Pregnolato F, Grossi C, Zanola A, Allegri F, Norman GL, Mahler M, Meroni PL, Angela T: Antiphospholipid Antibody Profiling: The Detection of IgG Antibodies Against beta2glycoprotein I Domain 1 and 4/5 Offers Better Clinical Characterization: The ratio between antiD1 and anti-D4/5 as a new useful biomarker for APS. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Oku K, Atsumi T, Bohgaki M, Amengual O, Kataoka H, Horita T, Yasuda S, Koike T: Complement activation in patients with primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis, 2009; 68: 1030-1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Lim W: Complement and the antiphospholipid syndrome. Curr Opin Hematol, 2011; 18: 361-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Erkan D, Aguiar CL, Andrade D, Cohen H, Cuadrado MJ, Danowski A, Levy RA, Ortel TL, Rahman A, Salmon JE, Tektonidou MG, Willis R, Lockshin MD: 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies: task force report on antiphospholipid syndrome treatment trends. Autoimmun Rev, 2014; 13: 685-696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Daha NA, Banda NK, Roos A, Beurskens FJ, Bakker JM, Daha MR, Trouw LA: Complement activation by (auto-) antibodies. Mol Immunol, 2011; 48: 1656-1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Raschi E, Testoni C, Borghi MO, Fineschi S, Meroni PL: Endothelium activation in the anti-phospholipid syndrome. Biomed Pharmacother, 2003; 57: 282-286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Lutters BC, Derksen RH, Tekelenburg WL, Lenting PJ, Arnout J, de Groot PG: Dimers of beta 2-glycoprotein I increase platelet deposition to collagen via interaction with phospholipids and the apolipoprotein E receptor 2′. J Biol Chem, 2003; 278: 33831-33838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Levine JS, Branch DW, Rauch J: The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med, 2002; 346: 752-763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Matsuura E, Shen L, Matsunami Y, Quan N, Makarova M, Geske FJ, Boisen M, Yasuda S, Kobayashi K, Lopez LR: Pathophysiology of beta2-glycoprotein I in antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus, 2010; 19: 379-384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Punnialingam S, Khamashta MA: Duration of anticoagulation treatment for thrombosis in APS: is it ever safe to stop? Curr Rheumatol Rep, 2013; 15: 318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Erkan D, Yazici Y, Peterson MG, Sammaritano L, Lockshin MD: A cross-sectional study of clinical thrombotic risk factors and preventive treatments in antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2002; 41: 924-929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Fischetti F, Durigutto P, Pellis V, Debeus A, Macor P, Bulla R, Bossi F, Ziller F, Sblattero D, Meroni P, Tedesco F: Thrombus formation induced by antibodies to beta2-glycoprotein I is complement dependent and requires a priming factor. Blood, 2005; 106: 2340-2346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Barbhaiya M, Erkan D: Primary thrombosis prophylaxis in antiphospholipid antibody-positive patients: where do we stand? Curr Rheumatol Rep, 2011; 13: 59-69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Giannakopoulos B, Krilis SA: How I treat the antiphospholipid syndrome. Blood, 2009; 114: 2020-2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Piazza G, Nguyen TN, Cios D, Labreche M, Hohlfelder B, Fanikos J, Fiumara K, Goldhaber SZ: Anticoagulation-associated adverse drug events. Am J Med, 2011; 124: 1136-1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40). Bertero MT: Primary prevention in antiphospholipid antibody carriers. Lupus, 2012; 21: 751-754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]