Abstract

Postpartum depression is a major mental health issue for women and society. We examined stability and change in symptoms of depression over two consecutive pregnancies and tested life stress as a potential mechanism. The Community Child Health Network followed an ethnically/racially diverse sample from one month after a birth for two years. A subset of 228 women had a second birth. Interview measures of depression symptoms (EPDS) and life stress (life events, perceived stress, chronic stress, interpersonal aggression) were obtained during home visits. Three-quarters of the sample showed intra-individual stability in depressive symptoms from one postpartum period to the next, and 24% of the sample had clinically significant symptoms after at least one pregnancy (9% first, 7.5% second, 3.5% both). Each of the four life stressors significantly mediated the association between depressive symptoms across two postpartum periods. Stress between pregnancies for women may be an important mechanism perpetuating postpartum depression.

Keywords: Postpartum depression, stress mechanisms, postpartum depressive symptoms, interpregnancy interval

Postpartum depression (PPD) affects half a million mothers in the United States each year (Horowitz & Goodman, 2005) and is manifested across cultures, though to varying degrees (Halbreich & Karkun, 2006). It is a form of depression indistinct from major depression in symptoms of sadness, anhedonia, and low self-worth. However, PPD is technically defined as an onset of major depressive disorder in the 4 weeks after childbirth (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In research, symptoms of depression occurring within a longer period of time, up to 6 months following childbirth, are often examined as potential or probable PPD (e.g., Beck, 2001; Cooper & Murray, 1995; O’Hara & Swain, 1996). Estimates of PPD prevalence in the U.S. range from 7 to 13% (Gavin, et al., 2005; Rich-Edwards et al., 2006), and the consequences can be serious for mothers and their families. For example, PPD is associated with problems in breastfeeding, infant-parent attachment, partner relationship, and possible infant cognitive, psychological, and behavioral detriments over the life course (Abrams & Curran, 2007; Hahn-Holbrook, Haselton, Dunkel Schetter, & Glynn, 2013). Evidence continues to grow regarding the adverse effects of a mother’s depressive symptoms following a birth.

Given the burden of postpartum depression, research has been directed toward identifying biological, social, and psychological risk factors for developing symptoms of depression in the postpartum period (see Yim, Tanner Stapleton, Guardino, Hahn-Holbrook, & Dunkel Schetter, 2015 for a review) with some conclusive findings. For example, one meta-analysis of 11 studies found that a history of non-puerperal depression is a clear and important risk factor for PPD (Beck, 2001; see also O’Hara & Swain, 1996). However, there is little systematic evidence concerning whether postpartum depressive symptoms following one pregnancy are associated with depressive symptoms following subsequent pregnancies, yet most women have more than one child. Thus, while the persistence of PPD over pregnancies has not been thoroughly investigated, a family’s concerns about reoccurrence may influence reproductive decision making. Analyses of data on depressive symptoms across two postpartum periods may inform, not only the targeting of intervention efforts, but women and their partners when facing a decision about whether to have another child after an experience of PPD.

A handful of studies on risk for PPD among mothers who experienced symptoms of depression following a previous pregnancy was published some years ago (Bratfos & Haug, 1966; Garvey, Tuason, Lumry, & Hoffmann, 1983; Reich & Winokur, 1970; Yalom, Lunde, Moos, & Hamburg, 1968), all suggesting that PPD predicted depression after subsequent pregnancies. However, these studies were limited by reliance on retrospective reports and uneven quality of symptom assessment. A more recent retrospective study of over 200 women referred for PPD found that nearly half (47%) of women with early onset PPD reported a history of the disorder, whereas only 22% of women with late onset of PPD reported such a history (Stowe, Hostetter, & Newport, 2005).

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) for the treatment of PPD also suggest that its occurrence after a pregnancy may be a risk factor for subsequent PPD (e.g., Okun, Hanusa, Hall, & Wisner, 2009; Okun et al., 2011; Wisner et al., 2001; Wisner, Perel, Peindl, & Hanusa, 2004a; Wisner et al., 2004b). For example, Wisner and colleagues have conducted trials in which they recruited pregnant women with a history of PPD and randomized them to a pharmaceutical or a placebo treatment. Although these studies use retrospective reports of postpartum depression history and involve small sample sizes, inferences may be made about the recurrence rate of PPD by examining the rates in the control groups. For instance, results of an RCT involving 51 women with a history of PPD indicated 25% (6 of 25) in the placebo group were diagnosed with a recurrence of PPD (Wisner et al., 2001). Other studies of this type report rates in that range as well (Okun et al., 2009, Okun et al., 2011, Wisner et al., 2004a). Comparing these estimates of reoccurrence of PPD to new incidence in second pregnancies is not possible, however, because women without prior PPD were not studied.

Finally, a few recent prospective studies have addressed the issue of whether an episode of PPD predicts subsequent episodes. In one such study, 34 women entered the study during their first PPD episode; of these, 41% had a later episode of PPD (Cooper & Murray, 1995). A larger prospective study of Australian women found that previous postpartum depression in either one’s self or one’s mother significantly predicted future postpartum depressive symptoms (Johnstone, Boyce, Hickey, Morris-Yates, & Harris, 2001).

Given the limited evidence and significant implications for women and their families, additional prospective research is needed to establish the extent to which postpartum depressive symptoms following one birth predicts risk for subsequent postpartum depressive symptoms after a subsequent pregnancy and birth. Furthermore, researchers have not examined mediators or moderators of recurrent PPD. Stress generation theory posits that people with depression experience more stressful life events and interpersonal disruptions as a function of their depressive state (Hammen, 1991). These life events and interpersonal difficulties, in turn, contribute to the persistence or worsening of depressive symptoms. Thus, life stress and depression can behave in a bidirectional or transactional manner (Alloy, Liu, & Bender, 2010). To our knowledge, this theory has not been applied to postpartum depression. Specifically, it is possible that various forms of stress that take place in a woman’s life during the intervening postpartum period and interpregnancy interval may increase the chances of recurrence of symptoms; in short, stressors would act as mediators. Examples of stressors that could plausibly mediate recurrence of PPD symptoms are chronic stress in the form of parenting stress, work, family or partner relationship strains, as well as acute episodes of severe life events such as death in a family, divorce, or job loss. A recent review found that parenting stress, chronic stress, perceived stress and severe life events appear to predict first incidence of PPD symptoms and disorders, although prospective studies were rare (Yim et al., 2015).

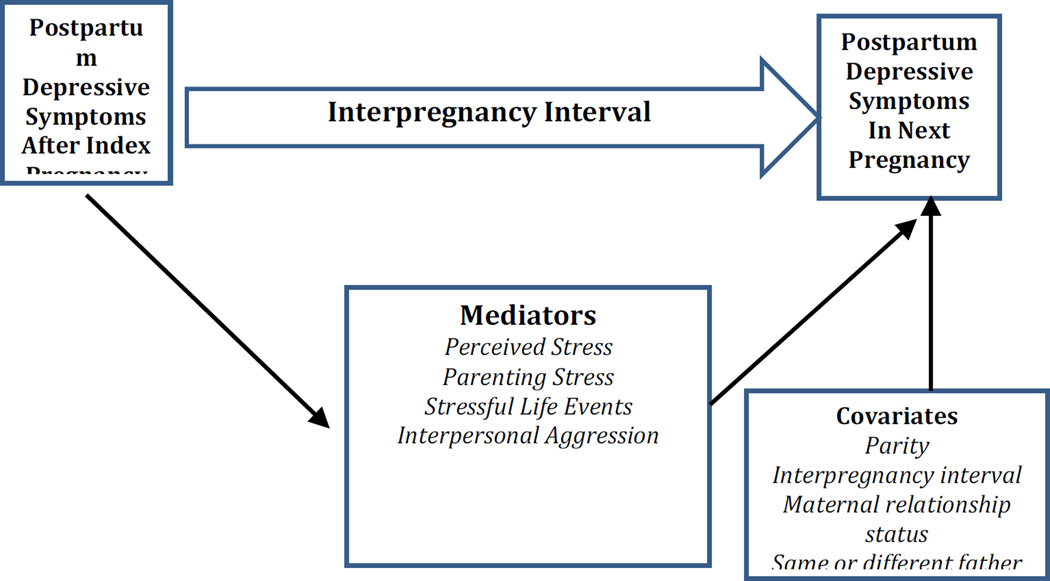

The present study utilized a relatively large sample of women with data on depressive symptoms collected prospectively over two postpartum periods. Figure 1 depicts the conceptual framework for this study, illustrating the pathway from one postpartum period to another and identifying hypothesized mediators and possible covariates. Regarding covariates, length of an interpregnancy interval is one key covariate. Shorter intervals, usually defined as 18 months or less between pregnancies, are associated with higher risk of adverse birth outcomes (Conde-Agudelo, Rosas-Bermudez, & Kafury-Goeta, 2006), possibly due to insufficient time for physiological recovery. Short intervals may also predict higher risk of PPD. Number of prior births is also important to control, as is a couple’s relationship status at the time of the second birth (i.e., cohabitating, married, or neither/single) because these factors may contribute to a woman’s overall stress burden during the interpregnancy interval. Women with more children and those who are single parents would be expected to have more stress. An additional covariate in this sample was whether the first and subsequent births involved the same or different fathers.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Mediators and Moderators of Recurrent PPD

The Current Study

The current study had two inter-related goals. First, since this is one of the first prospective studies on postpartum depressive symptoms following two different pregnancies, we sought to describe patterns of stability and change in symptoms. We hypothesized that maternal postpartum depressive symptoms following the birth of one child (Index Child) would be associated with more postpartum depressive symptoms after the birth of the next child (Subsequent Child).That is, we expected to see a fair degree of stability in mothers’ experiences of postpartum depressive symptoms (or absence of them) from one postpartum period to a subsequent postpartum period. Thus, mothers who had symptoms after one pregnancy would be at increased risk to experience them again after a subsequent pregnancy. We also tested whether depressive symptoms would increase or decrease in number (reflecting severity of depressive symptoms) in a subsequent pregnancy. On the one hand, it may be more challenging to adjust after a subsequent birth when parenting at least one other young child, which would increase risk for depression. On the other hand, it is possible that women will experience fewer symptoms following a subsequent pregnancy because a woman’s ability to cope and adjust to the demands of the postpartum period may improve with experience. These goals were tested in a relatively large and highly diverse community sample using community participatory methods.

Our second goal was to test life stress as a possible mechanism explaining the association between depressive symptoms from one postpartum period to the next. We hypothesized that psychosocial stress in the interval between the Index Child’s birth and the Subsequent Child’s birth would mediate associations between depressive symptoms in the two postpartum periods. Thus, higher postpartum depressive symptoms following the Index Child’s birth was expected to engender greater stress, which would in turn contribute to higher symptoms following the Subsequent Child’s birth. We tested this hypothesis using bootstrapping tests of mediation.

Methods

We utilized data from the Community and Child Health Network (CCHN), a five-site research network funded by The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development of NIH that was formed to investigate disparities in maternal child health and improve the health of families (Ramey et al., 2015). The overall goal of CCHN was to gain new insights into disparities in maternal health and child development through community-based participatory methods of research.

Participants

The sample was drawn from the larger pool of participants in the CCHN study, which includes 2,510 mothers, and 1,436 of the fathers of their children. Eligibility criteria, recruitment procedures, and cohort demographic characteristics are described elsewhere (Dunkel Schetter et al., 2013; Ramey et al., 2015). Briefly, mothers were recruited just after the birth of a child in one of five study sites: Washington, DC; Baltimore, MD; Los Angeles County, CA, Lake County, IL, and eastern North Carolina. The study catchment areas were predominantly low income. CCHN sampled only African American (54%), Latina (24%) and non-Hispanic white women (22%) and oversampled women who had delivered preterm infants. Fathers were invited to participate and provided separate informed consent if mothers agreed verbally for the study staff to contact them; only maternal data is used for the current study.

Eighty-three percent of the mothers in the full CCHN cohort completed at least one of five possible follow-up study visits held at six month intervals between six months and two years after the birth of the index child (n = 2089). During at least one of these visits, 372 participants (18%) reported that they were currently pregnant. Participants were also asked to contact study staff if they became pregnant again between study visits, and an additional 44 subsequent pregnancies were identified in this manner for a total of 416 subsequent pregnancies during the follow-up period. Most participants (n = 343, 82%) consented to continued participation in the subsequent pregnancy follow-up study and completed at least one study visit during or shortly after the subsequent pregnancy. The present sample includes only those women with subsequent pregnancies who completed a postpartum interview after the birth of the subsequent child (n = 228). A majority of the remaining 166 subsequent pregnancies were among women lost to follow up (n = 142). Another 12 women did not complete postpartum visits because the study ended before the P3 window opened. A few women withdrew from the study for reasons such as moving out of the study catchment area (n = 3), death of the index child (n = 2), stillbirth of the subsequent child (n =1), miscarriage (n = 4), lack of time/interest (n = 2). There were no differences in terms of income, race/ethnicity or cohabitation status between women with subsequent pregnancies who withdrew or were lost to follow-up and those with complete data included in the present sample. We also tested for differences in T1 depressive symptoms and there was no significant difference between the women with subsequent pregnancies who withdrew or were lost to follow-up (M = 4.80, SD = 4.70) and those who were included in the present study (M = 4.79, SD = 4.46).

Procedures

CCHN study visits occurred following a birth when the Index Children were approximately 1 month (T1), 6 months (T2), 12 months (T3), and 24 months (T5) of age with an additional telephone interview at 18 months (T4). Mothers who became pregnant again during this study period were interviewed during the second (P1) and third (P2) trimesters of their subsequent pregnancies, and then 6 to 20 weeks after the birth of the Subsequent Child (P3). Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish in participants’ homes, with attempts to match interviewer ethnicity to that of the participant.

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Participants completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987), a screening instrument validated for use during the first year postpartum. The EPDS assesses 10 common depressive symptoms (e.g., feeling sad or miserable, looking forward with enjoyment to activities, self-blame) experienced in the past 7 days. Items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, with higher ratings corresponding to greater symptoms, with total scores ranging 0 to 30. This instrument was completed at T1 (after the birth of the Index Child) and P3 (after the birth of the Subsequent Child). Participants had the option of completing the EPDS verbally or by written questionnaire to enhance open responding and confidentiality in the home if others were present. Means and ranges for these and other key variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Descriptive Information (n = 228)

| Range | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postpartum Depressive Symptoms (EPDS) | |||

| 1st (Index) Pregnancy | 0 – 18 | 4.79 | 4.46 |

| 2nd (Subsequent) Pregnancy | 0 – 20 | 4.12 | 4.47 |

| Interpregnancy Interval (in weeks) | 9 – 142 | 56.86 | 28.97 |

| Life Stress Mediators | |||

| Parenting Stress Index | 37 – 128 | 67.19 | 17.69 |

| Perceived Stress Score | 0 – 32 | 14.23 | 6.08 |

| Life Event Count | 0 – 12 | 3.67 | 2.83 |

| Interpersonal Violence Score | 5 – 17 | 6.20 | 2.09 |

Note: EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

Perceived stress

Perceived stress was measured at T3 using the 10-item brief version of the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Responses to the 10 items were each rated on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always) and summed after reverse-coding positively worded items. In the current study, Cronbach’s α was .85.

Parenting Stress

Parenting Stress was assessed at T3 using the 36-item short form of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI; Abidin, 1983), which includes subscales that measure mother’s distress, impaired interaction with child, and level of difficulty of infant’s behavior. All questions were coded on a 1–5 response scale, such that a higher score relates to more parenting stress and when summed, the composite score has a possible range of 36 to 180. Cronbach’s α for this measure was .92.

Life events

A life events checklist adapted from epidemiologic mental health research and used in several past maternal studies (Parker Dominguez, Dunkel Schetter, Mancuso, Rini and Hobel, 2005) was administered at T3. Participants reported whether each of 24 events occurred in the past year, and how negative or positive the impact of each event was. For the current analyses, we scored the total number of life events only (Life Event Count) with a range of 0 to 24.

Interpersonal violence

A modified version of a standard screener for family violence was administered to mothers at T3. The HITS includes four items related to physical Hurt, Insult, Threats, and Screaming (Sherin, Sinacore, Li, Zitter, & Shakil, 1998), plus an additional item regarding domination or emotional control (O’Campo, Caughy, & Nettles, 2010). Participants were asked how often the baby’s father, a partner, or anyone else in the household engaged in these actions towards her during the past year and responded using a 5-point frequency format (1 = never to 5 = frequently), with responses summed for a total score from 5 to 25. Cronbach’s α was .74.

Covariates

In testing the mediation models, all analyses controlled for four covariates: (1) parity (coded as 0 if the Index Child was the woman’s first birth child, 1 if she had given birth to any child preceding the Index Child); (2) the interpregnancy interval, or number of weeks between the Index Child’s birth and the first day of the last menstrual period before the subsequent pregnancy; (3) mothers’ relationship status at one year postpartum (e.g., if she was married or cohabiting, or neither/single), and (4) whether or not the Subsequent Child pregnancy was with the same father or a different father as the Index Child. Within our current sample, 51% of mother reported that the Index Child was their first born; for 33% of mothers, the Index Child was their second born child, and the Index Child was the third born child for 15% of mothers. Most mothers (93%) reported that the Subsequent Child pregnancy was with the same father as the Index Child pregnancy. Notably, a sizeable minority of mothers (31%) reported that they were neither married nor cohabiting at the 12-month interview though a majority were (69%).

Results

Table 2 presents zero order correlations between variables. As expected, postpartum depressive symptom scores in each of two subsequent pregnancies were significantly correlated, r (226) =.33, p=.001. A paired-samples t-test found that there was a decrease in symptoms during the postpartum from one postpartum period to the next, t (227) = 1.96, p=.051. Moreover, there was a great deal of heterogeneity in patterns of change. Specifically, 36% of the sample (81 women) showed a decrease in depressive symptoms over two postpartum periods. Another 20% of the sample (46 women) reported depressive symptom scores that were identical, and for 44% of the sample (101 women), depressive symptoms increased. Regardless of whether scores increased or decreased, 76% of the sample (173 women) had a negligible change in depressive symptoms (fewer than 5 points difference on the EPDS) from one postpartum period to the next. In the initial postpartum period, 13% of the sample (29 women) had clinically significant depressive symptoms (EPDS > 11) and 11% of the sample (25 women) had clinically significant symptoms in the subsequent postpartum period.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations between Key Study Variables (n = 228)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | T1 Depressive Symptoms | 1 | ||||||||

| (2) | P3 Depressive Symptoms | .33*** | 1 | |||||||

| (3) | T3 Parenting Stress Index | .29*** | .40*** | 1 | ||||||

| (4) | T3 Perceived Stress Score | .33*** | .43*** | .40*** | 1 | |||||

| (5) | T3 Life Event Count | .27*** | .27*** | .11+ | .32*** | 1 | ||||

| (6) | T3 Interpersonal Violence Score | .28*** | .30*** | .26*** | .33*** | .38*** | 1 | |||

| (7) | Parity | .19** | .03 | .12* | .06 | .07 | .10 | 1 | ||

| (8) | Interpregnancy interval (weeks) | −.12* | −.04 | −.01 | −.02 | .01 | .01 | −.07 | 1 | |

| (9) | T3 mother relationship status | −.06 | −.10 | −.13* | .17** | −.10+ | −.06 | −.04 | .03 | |

| (10) | Different father (T1 to P3) | .02 | .03 | .04 | .16** | .10 | .04 | −.03 | .12* | −.26*** |

Notes. Parity coded as 0 = index child is first child; 1 = mother had other children prior to index child. T3 mother relationship status coded as 0 = not married/not cohabitating; 1 = married/cohabitating. Different father coded as 0 =same father for index and subsequent pregnancy; 1 = different father for index and subsequent pregnancy.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

When we compared clinical cut-off categories between postpartum periods, 9% of the sample (21 women) showed clinically significant depressive symptoms after the index but not subsequent pregnancy, and 7.5% of the sample (17 woman) showed clinically significant symptoms in the second but not first postpartum period. Another 3.5% (8 women) showed clinically significant symptoms at both postpartum periods. Thus, the majority of the sample (80%) was non-depressed at both intervals. Finally, 8 of 29, or 28% of the women who had clinically significant PPD after the initial pregnancy had clinically significant PPD after the subsequent pregnancy.

One reason why postpartum depressive symptoms might show an average decline from one postpartum period to the next is that women who experienced PPD after one pregnancy might not choose to have subsequent children. However, we did not find support for this possibility. Within the full sample of 2,171 women who participated in the T1 interview but did not provide data during or after a subsequent pregnancy, 206 women (9.5%) showed clinically significant depressive symptoms after the index pregnancy. This rate is lower than the 13% rate found in the sample that was followed through a subsequent pregnancy and that reported on PPD depressive symptoms at both occasions. Thus, the evidence is counter to the possibility that women with postpartum depression following the birth of the index child were less likely to have another child.

The second main goal of the study was to identify variables that might mediate associations between depressive symptoms over two pregnancies. We specifically sought to test a stress generation model in which depression after one pregnancy contributed to greater life stress or interpersonal dysfunction, which then predicted more depressive symptoms following the subsequent pregnancy. In order to test this question, we performed bias-corrected bootstrapping tests of mediation to estimate confidence intervals using the SPSS macro described by Preacher & Hayes (2008), with index child postpartum depressive symptoms as our predictor and Subsequent Child postpartum depressive symptoms as the outcome variable. This approach uses bias-corrected bootstrapping techniques, a non-parametric method based on resampling with replacement, to estimate confidence intervals. Bootstrapping adjusts for uneven sampling distribution of indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) and is considered superior to normal theory tests for estimation of indirect effects (Hayes, 2009).

We tested four possible stressors as mediators, all of which were measured in the postpartum interview conducted one year following the index child’s birth. These mediators were perceived stress, parenting stress, number of stressful life events over the preceding year and interpersonal violence/aggression over the preceding year. Each mediator was tested in a separate model (four models run in total), each with the same four covariates included (number of previous pregnancies/births, maternal relationship status at one year postpartum, whether the two pregnancies had the same father, and interpregnancy interval in months). All four of these mediators passed the full mediation test (yielding 95% bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals not containing zero), specifically: 95% CI for parenting stress 0.05, 0.19, with a relative indirect effect (ratio of indirect effect to the total effect) = 0.34 (n=169); 95% CI for perceived stress 0.04–0.18; relative indirect effect = .32 (n=178); 95% CI for life event count 0.01, 0.10; relative indirect effect =.12 (n=178), and 95% CI for intimate partner aggression 0.02, 0.11, relative indirect effect = .19 (n=172). None of the four covariates was significant, and results were unchanged whether we included them in the model or dropped them.

In summary, each mediator explained a significant proportion of the variance linking depression following the birth of the Index Child to depression following the birth of the Subsequent Child. The largest indirect effects emerged for parenting stress and perceived stress, which were comparable in magnitude, while the life event count had the weakest indirect effect. According to these effect sizes, approximately one-third of the total effect of depression at the first assessment (following the birth of the Index Child) on depression at the next assessment (following the Subsequent Child) was mediated by parenting stress and perceived stress measured one year after the Index Child’s birth.

Discussion

This study is among the first to prospectively examine postpartum depressive symptoms following two pregnancies. We found indications of stability from one postpartum interval to the next, with most women showing only small changes in levels of depressive symptoms. However, there was also considerable variation within the sample in terms of whether symptoms increased or decreased, with an overall trend of symptoms decreasing slightly from one postpartum period to the next. A total of 24% of the sample had symptoms above clinical cutoffs after at least one of the two pregnancies. Thus, one in four women would warrant follow-up in the next pregnancy and postpartum period. Furthermore, among those with elevated PPD symptoms following one birth in this sample, 28% had a recurrence of clinically significant PPD symptoms following their next birth. Of note, this study is one of the first to examine PPD recurrence in a lower income, diverse, community-based sample. Therefore, our estimates of postpartum depression are relevant to a wider range of women in the population as compared to most prior studies.

In addition, this is the first study to test several forms of psychosocial stress assessed between births as potential mediators of recurrent PPD. That is, women who reported more depressive symptoms following the birth of one child were at risk of experiencing more stress thereafter, such as parenting and interpersonal difficulties, and these interpregnancy-interval stressors, in turn, exacerbated risk of depressive symptoms following a subsequent pregnancy. When each stress factor was tested separately, all four (perceived stress, parenting stress, stressful life events, and interpersonal aggression) measured at one year following the first birth emerged as mediators of the association between depressive symptoms over two consecutive postpartum periods. As would be expected, there were small to moderate associations among the four forms of stress, suggesting that they occurred independently as well as in combination (Dunkel Schetter et al., 2013 and supplementary materials). Thus, our findings strongly support the stress generation model and are consistent with prior evidence for non-pregnant samples,

One other mechanism possibly linking depressive symptoms following consecutive pregnancies is stable hormonal changes and other ongoing physiological factors such as maternal chronic inflammation. Also, recent work suggests that stress hormones, including products of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, may underlie the association between stress and postpartum depression found in the present study (Bloch, Daly, & Rubinow, 2003; de Rezende et al., 2016; Gobinath, Mahmoud, & Galea, 2014; Jolley, Elmore, Barnard, & Carr, 2007). These mechanisms deserve investigation, as do any genetic bases for them.

As in all correlational studies, many other factors may be involved as alternative explanations; accordingly, some key confounds – interpregnancy interval, relationship status, and prior births -- were controlled in these analyses. However, we could not control for additional factors in women’s lives in the interpregnancy interval such as changes in employment, or health or developmental issues in the index child. Nonetheless, these results are consistent with the interpretation that depression following one pregnancy increases risk for depression after the next, and that increased stress of many kinds is one pathway whereby this occurs. Randomized controlled intervention studies that aim to reduce the many possible forms of stress between pregnancies can further address issues of causality.

One of the plausible reasons that depressive symptoms might decline from pregnancy to pregnancy is that women who experienced PPD after one pregnancy might elect not to have subsequent children, or might be less likely to be retained in our sample for other reasons. We did not find support for these possibilities. The rate of postpartum depression was lower in the full CCHN sample of women who enrolled in the study but were not in the subsequent pregnancy cohort (9.5%) as compared to women in this cohort (13%). Thus, the evidence does not appear to support the possibility that women with PPD following the birth of the index child were less likely to have another child, or more likely to drop out. In addition, CCHN did a fairly good job of following women during the two years following a birth, and followed most women even longer, so differential loss in the subsequent pregnancy cohort is an unlikely concern.

The strengths of the study include the prospective longitudinal design along with the rare observation of two postpartum periods and in a relatively large sample. Another positive feature of the study is that this sample is predominantly low income, with a majority composed of women of color (Hispanic/Latino or African American Black) thereby adding to our understanding of a wider range of women during postpartum than much of prior research. The study was conducted with community partnership methods which enhanced recruitment, retention, rapport, and insight into the issues studied. In addition, the large and psychometrically strong set of measures available in this dataset is valuable for testing stress mediation. Although this paper does not focus on resilience, another CCHN paper examined postpartum depression among African American mothers (Cheadle, et al., 2015), indicating that resilience factors, spirituality and religiosity, predict lower risk of PPD.

Limitations of the study are perhaps that clinical diagnoses were not studied; rather, the study used a standardized postpartum depression screening tool to obtain a continuous measure of depressive symptoms. However, the particular screener used (the EPDS) is the worldwide “gold standard” for prenatal and postnatal depression screening and is well-validated for studying postpartum depression. Moreover, even subclinical elevations in depressive symptoms have implications for parenting and a mother’s functioning in multiple roles (Moehler, Brunner, Wiebel, Reck, & Resch, 2006; Tanner Stapleton et al., 2012). Many researchers feel that symptom measures, in and of themselves, are valuable when viewed in concert with studies of clinical diagnoses of more severely depressed women.

Of note, the depressive symptom screening measure used here is also appropriate for new fathers. Emerging research indicates that fathers experience depression following birth at much higher rates compared to men in the general population (Garfield, et al., 2014; Paulson, & Bazemore, 2010). Thus, consideration of predictors and mechanisms of depression in fathers (Bamishigbin et al., in press; Wee, Skouteris, Pier, Richardson & Milgrom, 2011), and in both parents simultaneously following birth (Pinheiro, et al., 2006; Saxbe et al., under review) warrant attention as well as research on maternal PPD risk. Our finding that stress appears to mediate associations between depressive symptoms following two pregnancies may be relevant to fathers as well, given that parenting stress, perceived stress, and life event stress may all be shared within couples. We also identified intimate partner violence as a mediator, suggesting that fathers who are aggressive to their partners may contribute to the persistence of depression across multiple pregnancies.

Recent and widely publicized consensus reports call for screening all women in pregnancy and postpartum for depressive symptoms due to the epidemic nature of this problem and the seriousness of the consequences. Our findings point to the possibility that such screening should also take into account not only a history of depression before pregnancy, but also prior symptoms of PPD following earlier pregnancies and sources of life stress (including life events, parenting stress, and intimate partner aggression) between pregnancies.

The most promising intervention for depression is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which can be delivered to women with a history of depression who have not been previously treated. For those who have been previously treated, refresher therapy may be advisable (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006). In addition, there are now promising web-based versions of CBT (Craske et al, 2009; Craske, et al., 2011). A critical issue is the timing of treatment. Ideally, we need to prepare women for pregnancy by screening and providing treatment for affective disorders prior to conception. In fact, a population-wide approach to depression screening and treatment is now seeing some progress (Sui et al., 2016). Insurance coverage for mental health treatment in young women before a first pregnancy (preconception prevention) stands to contribute substantially to the reduction of PPD, as do mental health parity laws that ensure psychological treatment is made widely available.

In closing, this study fills gaps in understanding the pattern of depressive symptoms over pregnancies and their mediators in a diverse population. In light of the worldwide burden of depression in general (Whiteford et al., 2011), and the specific burden of depression for mothers of an infant, it behooves us to make use of this new evidence if we are to increase the health of mothers, fathers, and their children. How might we do that? First, informing women of the facts and findings regarding risks for PPD based on solid evidence is of utmost importance, both before they become pregnant, certainly during pregnancy, and also following pregnancy when symptoms may emerge at home. Second, widespread screening efforts are justified beginning during pregnancy and through postpartum but such practices must be accompanied by diagnosis and treatment, both of which are far too often lacking in the healthcare system in the US presently. We know of one incident in which a mother who had a preconception history of depression was screened in a major medical center within 48 hours of her birth but the follow-up to the screening was inadequate and insensitive. This should not be the case. We must do better to attend to the needs of mothers sensitively and comprehensively if we are to make inroads into this problem. Finally, our data suggest that among the women most at risk of PPD are mothers that had depressive symptoms following a prior birth, particularly when life stress is also elevated. Therefore, efforts to monitor and assist these women in particular can begin before they give birth.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on data from the Child Community Health Network (CCHN), supported through cooperative agreements with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U HD44207, U HD44219, U HD44226, U HD44245, U HD44253, U HD54791, U HD54019, U HD44226-05S1, U HD44245-06S1, R03 HD59584) and the National Institute for Nursing Research (U NR008929). Members of each site are listed below.

-

Baltimore, MD: Baltimore City Healthy Start, Johns Hopkins University

Community PI: M. Vance

Academic PI: C. S. Minkovitz; Co-Invs: P. O’Campo, P. Schafer

Project Coordinators: N. Sankofa, K. Walton

-

Lake County, IL: Lake County Health Department and Community Health Center, the North Shore University Health System

Community PI: K. Wagenaar

Academic PI: M. Shalowitz

Co-Invs: E. Adam, G. Duncan*, A. Schoua-Glusberg, C. McKinney, T. McDade, C. Simon

Project Coordinator: E. Clark-Kauffman

-

Los Angeles, CA: Healthy African American Families, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, University of California, Los Angeles

Community PI: L. Jones

Academic PI: C. Hobel; Co-PIs: C. Dunkel Schetter, M. C. Lu; Co-I: B. Chung

Project Coordinators: F. Jones, D. Serafin, D. Young

-

North Carolina: East Carolina University, NC Division of Public Health, NC Eastern Baby Love Plus Consortium, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Community PIs: S. Evans, J. Ruffin, R. Woolard

Academic PI: J. Thorp; Co-Is J. DeClerque, C. Dolbier, C. Lorenz

Project Coordinators L. S. Sahadeo, K. Salisbury

-

Washington, DC: Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, Virginia Tech, Washington Hospital Center, Developing Families Center

Community PI: L. Patchen

Academic PI: S. L. Ramey; Academic Co-PI R.Gaines Lanzi

Co-Invs: L. V. Klerman, M. Miodovnik, C. T. Ramey, L. Randolph

Project Coordinator: N. Timraz

Community Coordinator: R. German

-

Data Coordination and Analysis Center DCAC (Pennsylvania State University)

PI: V. M. Chinchilli

Co-Invs: R, Belue, G. Brown Faulkner*, M, Hillemeier, I. Paul, M. L. Shaffer

Project Coordinator: G. Snyder

Biostatisticians: E. Lehman, C. Stetter

Data Managers: J. Schmidt, K. Cerullo, S. Whisler

Programmers: J. Fisher, J, Boyer, M. Payton

NIH Program Scientists: V. J. Evans and T. N.K. Raju, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; L. Weglicki, National Institute of Nursing Research, Program Officers: M. Spittel* and M. Willinger, NICHD; Y. Bryan,* NINR.

Steering Committee Chairs: M. Phillippe (University of Vermont) and E. Fuentes-Afflick* (University of California - San Francisco School of Medicine)

*Indicates those who participated in only the planning phase of the CCHN.

References

- Abidin RR. The Parenting Stress Index. Charlottesville, VA: Pediatric Psychology Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams LS, Curran L. Not just a middle-class affliction: Crafting a social work research agenda on postpartum depression. Health & Social Work. 2007;32(4):289–296. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.4.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Liu RT, Bender RE. Stress generation research in depression: A commentary. International journal of cognitive therapy. 2010;3(4):380. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2010.3.4.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bamishigbin ON, Dunkel Schetter C, Guardino CM, Stanton AL, Schafer P, Shalowitz M, Gaines Lanzi R, Thorp J, Raju T the Community Child Health Network. Risk, resilience, and depressive symptoms in low-income African American fathers. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000088. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression. Nursing Research. 2001;50(5):275–285. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch M, Daly RC, Rubinow DR. Endocrine factors in the etiology of postpartum depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44(3):234–246. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratfos O, Haug JO. Puerperal mental disorders in manic-depressive females. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1966;42(3):285–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1966.tb01933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle AC, Dunkel Schetter C, Lanzi RG, Vance MR, Sahadeo LS, Shalowitz MU the Community Child Health Network. Spiritual and Religious Resources in African American Women Protection From Depressive Symptoms After Childbirth. Clinical Psychological Science. 2015;3(2):283–291. doi: 10.1177/2167702614531581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295(15):1809–1823. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.15.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper P, Murray L. Course and recurrence of postnatal depression. Evidence for the specificity of the diagnostic concept. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;166(2):191–195. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Rose RD, Lang A, Welch S, Campbell-Sills L, Sullivan G, Sherbourne C, Bystritsky A, Stein MB, Roy-Byrne PP. Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in primary care settings. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:235–242. doi: 10.1002/da.20542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Stein MB, Sullivan G, Sherbourne C, Bystritsky A, Rose D, Lang AJ, Welch S, Campbell-Sills L, Golinelli D, Roy-Byrne P. Disorder specific impact of CALM treatment for anxiety disorders in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:378–388. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rezende MG, Garcia-Leal C, de Figueiredo FP, de Carvalho Cavalli R, Spanghero MS, Barbieri MA, Del-Ben CM. Altered functioning of the HPA axis in depressed postpartum women. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;193:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel Schetter C, Schafer P, Lanzi RG, Clark-Kauffman E, Raju TNK, Hillemeier MM. Shedding light on the mechanisms underlying health disparities through community participatory methods: The stress pathway. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(6):613–633. doi: 10.1177/1745691613506016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield CF, Duncan G, Rutsohn J, McDade TW, Adam EK, Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL. A longitudinal study of paternal mental health during transition to fatherhood as young adults. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):836–843. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey MJ, Tuason VB, Lumry AE, Hoffmann NG. Occurrence of depression in the postpartum state. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1983;5(2):97–101. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(83)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005;106(5, pt 1):1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobinath AR, Mahmoud R, Galea LA. Influence of sex and stress exposure across the lifespan on endophenotypes of depression: focus on behavior, glucocorticoids, and hippocampus. Front Neuroscience. 2014;8:420. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn-Holbrook J, Haselton MG, Dunkel Schetter C, Glynn LM. Does breastfeeding offer protection against maternal depressive symptomatology? Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2013;16(5):411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0348-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbreich U, Karkun S. Cross-cultural and social diversity of prevalence of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;91(2–3):97–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76(4):408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JA, Goodman JH. Identifying and treating postpartum depression. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2005;34(2):264–273. doi: 10.1177/0884217505274583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone SJ, Boyce PM, Hickey AR, Morris-Yates AD, Harris MG. Obstetric risk factors for postnatal depression in urban and rural community samples. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;35(1):69–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley SN, Elmore S, Barnard KE, Carr DB. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in postpartum depression. Biological Research for Nursing. 2007;8(3):210–222. doi: 10.1177/1099800406294598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehler E, Brunner R, Wiebel A, Reck C, Resch F. Maternal depressive symptoms in the postnatal period are associated with long-term impairment of mother-child bonding. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2006;9:273–278. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Campo P, Caughy MO, Nettles SM. Partner abuse or violence, parenting and neighborhood influences on children’s behavioral problems. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(9):1404–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression-a metaanalysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Okun ML, Hanusa BH, Hall M, Wisner KL. Sleep complaints in late pregnancy and the recurrence of postpartum depression. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2009;7(2):106–117. doi: 10.1080/15402000902762394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun ML, Luther J, Prather AA, Perel JM, Wisniewski S, Wisner KL. Changes in sleep quality, but not hormones predict time to postpartum depression recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;130(3):378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker Dominguez T, Dunkel Schetter C, Mancuso R, Rini CM, Hobel C. Stress in African-American pregnancies: Testing the roles of various stress concepts in prediction of birth outcomes. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29(1):12–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2901_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson JF, Bazemore SD. Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(19):1961–1969. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro RT, Magalhães PVS, Horta BL, Pinheiro KAT, Da Silva RA, Pinto RH. Is paternal postpartum depression associated with maternal postpartum depression? Population-based study in Brazil. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113(3):230–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey SL, Schafer P, DeClerque JL, Lanzi RG, Hobel C, Shalowitz M Community Child Health Network. The preconception stress and resiliency pathways model: A multi-level framework on maternal, paternal, and child health disparities derived by community-based participatory research. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2015;19(4):707–719. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich T, Winokur G. Postpartum psychoses in patients with manic depressive disease. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1970;151(1):60–68. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman K, Abrams A, Harlow BL, McLaughlin TJ, Joffe H, Gillman MW. Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60(3):221–227. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, Zitter RE, Shakil A. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Family Medicine. 1998;30(7):508–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe ZN, Hostetter AL, Newport DJ. The onset of postpartum depression: Implications for clinical screening in obstetrical and primary care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;192(2):522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, Ebell M, Krist AH. Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380–387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner Stapleton LR, Dunkel Schetter C, Westling E, Rini C, Glynn LM, Hobel CJ, Sandman CA. Perceived partner support in pregnancy predicts lower maternal and infant distress. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26(3):453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0028332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee KY, Skouteris H, Pier C, Richardson B, Milgrom J. Correlates of ante-and postnatal depression in fathers: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;130(3):358–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, Vos T. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Perel JM, Peindl KS, Hanusa BH, Findling RL, Rapport D. Prevention of recurrent postpartum depression: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62(2):82–86. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Perel JM, Peindl KS, Hanusa BH. Timing of depression recurrence in the first year after birth. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004a;78(3):249–252. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Perel JM, Peindl KS, Hanusa BH, Piontek CM, Findling RL. Prevention of postpartum depression: A pilot randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004b;161(7):1290–1292. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalom ID, Lunde DT, Moos RH, Hamburg DA. Postpartum blues syndrome: A description and related variables. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1968;18(1):16–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1968.01740010018003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim IS, Tanner Stapleton LR, Guardino CM, Hahn-Holbrook J, Dunkel Schetter C. Biological and psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression: Systematic review and call for integration. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2015;11:99–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-101414-020426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]