Abstract

PURPOSE

Preoperative detection of intrahepatic bile duct (IHBD) variations is essential to reduce surgical morbidity and mortality rates. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a noninvasive and reliable method for demonstrating the normal IHBD anatomy and its variations. This retrospective study aimed to identify and classify novel variations, except those already reported in the literature, using MRCP.

METHODS

MRCP examinations, which were conducted in two different centers in the last five years, were retrospectively evaluated. IHBD variations were recorded with respect to the Yoshida classification. In addition, newly detected variations that were not included in this classification were identified and classified.

RESULTS

MRCP examinations of 2624 patients were screened, and 2143 were determined to be eligible for evaluation. Of 2143 patients, 987 were males (average age, 54±18 years) and 1156 were females (mean age, 57±17 years). In this study, 10 novel variations that were not included in the Yoshida classification were identified in 14 patients.

CONCLUSION

MRCP is an effective, reliable, and noninvasive imaging method for evaluating the IHBD anatomy and its variations. Novel variations described in this study may help to better understand the biliary anatomy.

Intrahepatic bile duct (IHBD) anatomy can show many variations causing biliary complications after liver transplantation (1). Biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantations are reported in 10%–25% of subjects, and fatal complications can be observed in up to 10% of patients in complicated cases. In addition, although laparoscopic surgery is a less invasive surgical method, the limited visual field and errors of misperception occasionally result in biliary complications such as bile leakage and injury to the contralateral biliary ducts (approximately 0.5% of cases) (2). It is very important to preoperatively delineate the anatomy of the biliary system in an accurate and reliable manner. Inadequate characterization of the IHBD anatomy can cause not only perioperative but also postoperative complications that can adversely affect the prognosis.

With the technological developments in recent years, it has become possible to noninvasively depict biliary structures using imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiography, and computed tomography cholangiography. Noninvasive imaging modalities have emerged as invaluable alternatives for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and perioperative cholangiography. MRCP is the foremost noninvasive imaging method of the biliary system. Maximum-intensity projection (MIP) images obtained using MRCP enable the assessment of small biliary tracts. Furthermore, MRCP is not associated with radiation exposure and does not require a contrast material (3–5).

Despite many different IHBD variations reported, the most comprehensive classification is the Yoshida classification (6). This classification describes seven different IHBD variations. Cystohepatic duct is accepted as the eighth type in this study. In the literature, there are many case reports on different variations that were not presented in the Yoshida classification. Therefore, this study aimed to form a wide novel classification for IHBD variations.

Methods

The institutional ethics board approval was obtained, and the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived. MRCP studies that were performed over a 60-month period (from January 2011 to December 2015) at two university hospitals were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with a minimum age of 18 years who had undergone MRCP were included. The exclusion criteria were the lack of adequate quality of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), history of previous surgery, distortion of the biliary tracts because of a tumor or another space-occupying lesion, and cases with poor anatomic delineation because of an excessive dilation of the biliary tracts. Patients were selected from a cohort of 2624 consecutive patients for whom MRCP was obtained. Seventy-three patients below the age of 18 years were excluded. Furthermore, 408 patients were excluded because of motion artifacts or excessive dilation of the biliary tracts in MRI scans, and 2143 patients (Table 1) were included in the final study group. A flowchart for evaluating the MRI scans according to exclusion criteria is shown in Fig. 1. All MRCP studies were initially evaluated by one observer. When a nonclassified variation was encountered, the case was reevaluated by another observer who was experienced in abdominal radiology.

Table 1.

Indications for magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography examination

| Initial diagnosis and clinical condition | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Cholelithiasis (preoperative assessment) | 626 (29.2) |

| Obstructive jaundice | 593 (27.6) |

| Choledocholithiasis | 284 (13.3) |

| Acute cholecystitis | 132 (6.2) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 128 (5.9) |

| Donor for liver transplantation | 83 (3.9) |

| Liver mass | 82 (3.8) |

| Pancreatic mass | 65 (3) |

| Klatskin tumor | 51 (2.4) |

| Postcholecystectomy control | 49 (2.3) |

| Acute cholangitis | 34 (1.6) |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 16 (0.8) |

| Overall | 2143 |

Figure 1.

A flowchart showing the evaluation of the MRI data according to the exclusion criteria.

MRCP protocol

MRI was performed using 1.5 T units (Siemens, Avanto and Siemens, Aera) using a body coil. All patients were imaged in the supine position. Our protocol included a done set of breath-hold coronal half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin echo (HASTE) (TR/TE, 1400/91 ms; flip angle, 180°; slice thickness, 6 mm; FOV, 400×400), axial and coronal fat-saturated HASTE (TR/TE, 1200/94 ms; flip angle, 160°; slice thickness, 3 mm; FOV, 400×400), and a set of three dimensional (3D) oblique coronal thin slice, fast spin echo T2-weighted images (TR/TE, 2500/700 ms; flip angle, 140°; slice thickness, 1 mm). Post-processing of the image data was performed to reconstruct MIP images.

Evaluation of the normal IHBD anatomy and its variations

The biliary tree runs parallel to the hepatic artery and portal vein branches through the liver parenchyma. Venous, arterial, and IHBD anatomic variations are quite common in the hepatobiliary system. Two biliary ducts draining the right liver lobe and a single duct formed by segmental tributaries draining the left lobe is the most common anatomic variation and is considered as “normal biliary anatomy.” IHBD variations have been classified into seven groups by Yoshida et al. (6). Cystohepatic duct is accepted as the eighth type in this study. In this study group, anatomic variations were assessed according to the Yoshida classification, and 10 novel variations with anatomic and surgical importance were described.

Results

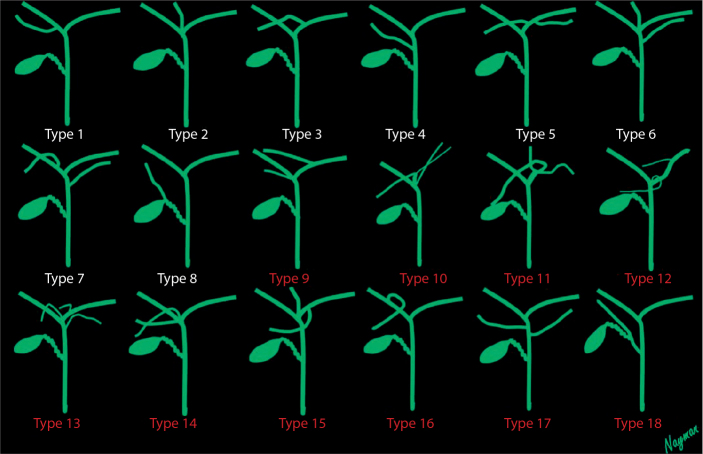

IHBDs of 2143 patients (987 males 54±18 years of age and 1156 females 57±17 years of age), were evaluated using 3D oblique coronal thin slice fast spin-echo T2-weighted images and reformat (MIP) images. Variation types 1, 2, and 3 were the most common variations, similar to the findings of previous studies. Variation types 4–7 were less frequently observed. Ten novel IHBD variations were encountered that were not included in the Yoshida classification. Frequency of variations in the Yoshida classification were as follows: Type 1, 62% (1329 patients); Type 2, 9% (202 patients); Type 3, 11% (245 patients); Type 4, 7% (149 patients); and the other types (5, 6, and 7), 10% (203 patients). The cystohepatic duct, which is defined as a bile duct of the aberrant right lobe that opens into the cystic duct, is commonly noted in the literature; this was defined as Type 8 in this study. Type 8 was seen in one patient (%0.05). The 10 novel IHBD variations were defined as Types 9–18 (Figs. 2–12). Types 10 and 14 were observed in two patients, and Type 17 was observed in three patients. Each of the other types was observed in one patient (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Intrahepatic bile duct variations. Types 1–8, previously classified types. Types 9–18, novel defined variants.

Figure 3.

Novel Type 9: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) image with an illustration showing the trifurcation associated with right segmental duct draining into the left main biliary duct.

Figure 4.

Novel Type 10: MRCP image with an illustration showing the accessory segmental right and left intrahepatic duct forming a truncus and the truncus draining into the common hepatic duct (CHD).

Figure 5.

Novel Type 11: MRCP image with an illustration showing the trifurcation associated with right segmental duct draining into CHD.

Figure 6.

Novel Type 12: MRCP image with an illustration showing the two right segmental ducts draining into the left main biliary duct.

Figure 7.

Novel Type 13: MRCP image with an illustration showing the trifurcation associated with right segmental duct draining into the left main biliary duct and left segmental duct draining into CHD.

Figure 8.

Novel Type 14: MRCP image with an illustration showing the trifurcation formed by three right segmental ducts.

Figure 9.

Novel Type 15: MRCP image with an illustration showing the trifurcation associated with right segmental duct draining into the left main biliary duct.

Figure 10.

Novel Type 16: MRCP image with an illustration showing the right posterior segmental duct that passes caudally in contrast with Yoshida Type 1.

Figure 11.

Novel Type 17: MRCP image with an illustration showing the accessory right and left segmental ducts draining into CHD.

Figure 12.

Novel Type 18: MRCP image with an illustration showing the accessory right segmental duct draining into CHD and cystic duct draining into this accessory right segmental duct.

Table 2.

Novel intrahepatic bile duct variation types related to patient characteristics

| Novel intrahepatic bile duct variation types | Number of patient(s) | Age (years) | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 9 | 1 | 46 | M |

|

| |||

| Type 10 | 2 | 55 | M |

| 65 | M | ||

|

| |||

| Type 11 | 1 | 52 | F |

|

| |||

| Type 12 | 1 | 68 | F |

|

| |||

| Type 13 | 1 | 27 | F |

|

| |||

| Type 14 | 2 | 84 | F |

| 65 | M | ||

|

| |||

| Type 15 | 1 | 71 | M |

|

| |||

| Type 16 | 1 | 73 | M |

|

| |||

| Type 17 | 3 | 58 | F |

| 41 | F | ||

| 32 | M | ||

|

| |||

| Type 18 | 1 | 33 | F |

|

| |||

| Overall | 14 | ||

M, male; F, female.

Discussion

This study shows that IHBD anatomy and variations can be evaluated safely and noninvasively via MRCP. Many novel variations outside the classifications reported in the literature were also presented in this study.

Variations in arterial, venous, and ductal structures of the hepatopancreaticobiliary system are frequently observed. The reason for the frequency of IHBD variations in this system is clockwise rotation at the fourth to seventh embryologic weeks at the level of the midgut and foregut junction (7). According to the literature, the proportion of variations, except the typical pattern of the biliary tract (Yoshida Type 1), varies between 28% and 43% (1, 8–13).

The number of hepatobiliary surgeries has increased, which particularly includes laparoscopic cholecystectomy, transplantation surgery, hepatic resection, and tumor surgery. Complications related to the biliary system constitute one of the most common reasons for morbidity and mortality in these surgeries. To minimize peri- and postoperative morbidity and mortality, a detailed evaluation of the biliary anatomy is essential before surgery (1). In traumatic or iatrogenic biliary damage, in which biliary drainage is disrupted, jaundice, bilioma, biliary peritonitis, sepsis, and biliary fistula may develop within 1–2 weeks (14, 15). Recurrent and secondary biliary cirrhosis in segments or lobes with disrupted drainage may develop over the long term (months/years) (15, 16).

Various diagnostic methods can be used to evaluate the biliary anatomy in the preoperative period (conventional T2-weighted MRCP, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRCP, and multidetector row CT cholangiography) or during surgery (intraoperative cholangiography). Among these, the most commonly used method is MRCP, since it is noninvasive and does not require a contrast material. MRCP relies on heavily T2-weighted images that produce a high signal from the static fluid. This method can noninvasively display the anatomy of the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tract, with a high sensitivity and specificity (3–5). In many centers, MRCP is routinely used to image the bile duct anatomy and for surgical planning before live donor liver transplantation (LDLT), laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and extensive liver surgeries (9). The success of major liver surgeries and a decrease in biliary complications are closely related to a better evaluation of the biliary anatomy and the identification of anatomic variations. In this respect, MRCP is an indispensable, noninvasive method.

The proper evaluation of the IHBD anatomy and its variations before liver transplantation and extensive liver resection is very important (17). LDLT using the right lobe has become a standard operation (18). Nakamura et al. (18) conducted a study with 120 patients with right lobe LDLT and reported that there was no absolute contraindication related to the variations of the biliary system for transplantation. Varotti et al. (19) conducted a study with 96 donors of the right liver lobe and reported that the variations of the biliary system were frequently observed, and these variations were not contraindicated for transplantation; however, an accurate pre- and intraoperative evaluation was required for successful transplantation planning. For example, in a patient with Type 3 bile duct variation according to the Yoshida classification, the right posterior branch can be ligated during left hepatectomy, which can cause cirrhosis development at segments 6/7. However, studies have reported that Type 2 bile duct pattern is contraindicated for safe right lobe donation and the Type 3 bile duct pattern is also contraindicated for both right and left lobe donations (2, 20). The risk for biliary complication is high in the first situation because of the necessity of additional anastomosis in the recipient and in the second situation because of the risk of the right posterior branch injury during left hepatectomy. In addition, biliary variations are a major source of morbidity and mortality after transplantation (1, 19). The current study included novel IHBD variations that can cause bile duct complications for LDLT, namely, types 9, 11, 12, 13, and 15 (Figs. 3, 5–7, 9). The abovementioned types have aberrant IHBDs, which drain to the bile duct of the contralateral lobe.

Laparoscopic surgery has become the standard approach for cholecystectomy (21). As biliary tract variations are observed quite often, an evaluation of bile duct variations with MRCP before laparoscopic cholecystectomy is very important to prevent biliary complications because of ductal injuries such as bile leakage, bile peritonitis, biliary stricture, obstructive jaundice, and liver abscess (21). Poor visualization of the cystic duct during surgery may cause accidental bile duct injury. Although the overall incidence of bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is usually lower than 1%, they often emerge in the form of serious complications (2, 9, 22–25). For example, aberrant right posterior duct draining into the common hepatic or cystic duct or draining of the cystic duct into the right hepatic duct (Fig. 12) may cause ligation or inadvertent injury of these branches (9). An unnoticed bile duct during surgery may cause bile peritonitis or bilioma that develop 5–7 days postoperatively. If not treated, the mortality rate can be as high as 44% (26). Except iatrogenic complications during surgery, other complications include bile duct calculi formation, pancreatitis, and cholangitis (26, 27). In the current study, one of the novel variations (Type 18) was noted to be prone to bilioma, bile peritonitis, and intrahepatic biliary obstruction development after laparoscopic surgery (Fig. 12). In patients with Type 18 bile duct variation, aberrant right IHBD may be damaged during ligation and removal of cystic duct, which may lead to bile leakage and bile peritonitis.

This study had some limitations. The most important one is spatial resolution, which is an inevitable limitation of MRI and MRCP. Another is that this study was conducted in a nondilated biliary system and only the main branches of the biliary tract were observed; terminal branches were not evaluated. To evaluate the terminal branches, morphine, fentanyl, and secretin should be used to increase the contractions of sphincter of Oddi (1, 28–31), which are not used in our routine practice.

In conclusion, biliary tract-induced complications in hepatobiliary surgery are important causes of morbidity and mortality. MRCP is a noninvasive and reliable method to evaluate the IHBD anatomy and its variations in the preoperative period. There are many variations outside the classifications reported in the literature, and these novel variations were also classified in this study. This study highlights the clinical and surgical importance of the newly identified variants.

Main points.

The majority of complications that cause morbidity and mortality in hepatobiliary surgery are related to the biliary system variations.

MRCP is a noninvasive, efficient, and reliable imaging method for evaluating the intrahepatic bile duct anatomy and its variations.

Ten novel variations are reported in this study, outside the reported classifications.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lyu S-Y, Pan K-T, Chu S-Y, et al. Common and rare variants of the biliary tree: magnetic resonance cholangiographic findings and clinical implications. J Radiol. 2012;37:59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyodo T, Kumano S, Kushihata F, et al. CT and MR cholangiography: advantages and pitfalls in perioperative evaluation of biliary tree. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:887–896. doi: 10.1259/bjr/21209407. http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/bjr/21209407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindsell DR. The diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and ultrasound compared with direct cholangiography in the detection of choledocholithiasis. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:579. doi: 10.1053/crad.1999.0426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/crad.1999.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angulo P, Pearce DH, Johnson CD, et al. Magnetic resonance cholangiography in patients with biliary disease: its role in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2000;33:520–527. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004520.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sirinek KR, Schwesinger WH. Has intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy become obsolete in the era of preoperative endoscopic retrograde and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography? J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:522–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida J, Chijiiwa K, Yamaguchi K, Yokohata K, Tanaka M. Practical classification of the branching types of the biliary tree: an analysis of 1,094 consecutive direct cholangiograms. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;182:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mortele KJ, Rocha TC, Streeter JL, Taylor AJ. Multimodality imaging of pancreatic and biliary congenital anomalies. Radiographics. 2006;26:715–731. doi: 10.1148/rg.263055164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/rg.263055164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang TL, Cheng YF, Chen CL, Chen TY, Lee TY. Variants of the bile ducts: clinical application in the potential donor of living-related hepatic transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1996;28:1669–1670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mortele KJ, Ros PR. Anatomic variants of the biliary tree: MR cholangiographic findings and clinical applications. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:389–394. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.2.1770389. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.177.2.1770389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi JW, Kim TK, Kim KW, et al. Anatomic variation in intrahepatic bile ducts: an analysis of intraoperative cholangiograms in 300 consecutive donors for living donor liver transplantation. Korean J Radiol. 2003;4:85–90. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2003.4.2.85. http://dx.doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2003.4.2.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CM, Chen HC, Leung TK, Chen YY. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography of anatomic variants of the biliary tree in Taiwanese. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103:155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puente SG, Bannura GC. Radiological anatomy of the biliary tract: variations and congenital abnormalities. World J Surg. 1983;7:271–276. doi: 10.1007/BF01656159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01656159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohkubo M, Nagino M, Kamiya J, et al. Surgical anatomy of the bile ducts at the hepatic hilum as applied to living donor liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2004;239:82–86. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000102934.93029.89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000102934.93029.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll BJ, Birth M, Phillips EH. Common bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy that result in litigation. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:310–313. doi: 10.1007/s004649900660. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s004649900660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keulemans YC, Bergman JJ, de Wit LT, et al. Improvement in the management of bile duct injuries? J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:246–254. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00155-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1072-7515(98)00155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connor S, Garden OJ. Bile duct injury in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The Br J Surg. 2006;93:158–168. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.5266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mariolis-Sapsakos T, Kalles V, Papatheodorou K, et al. Anatomic variations of the right hepatic duct: results and surgical implications from a cadaveric study. Anat Res Int. 2012;2012:838179. doi: 10.1155/2012/838179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura T, Tanaka K, Kiuchi T, et al. Anatomical variations and surgical strategies in right lobe living donor liver transplantation: lessons from 120 cases. Transplantation. 2002;73:1896–1903. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206270-00008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00007890-200206270-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varotti G, Gondolesi GE, Goldman J, et al. Anatomic variations in right liver living donors. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.11.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee VS, Morgan GR, Teperman LW, et al. MR imaging as the sole preoperative imaging modality for right hepatectomy: a prospective study of living adult-to-adult liver donor candidates. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1475–1482. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.6.1761475. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.176.6.1761475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minutoli F, Naso S, Visalli C, et al. A new variant of cholecystohepatic duct: MR cholangiography demonstration. Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37:539–541. doi: 10.1007/s00276-014-1356-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00276-014-1356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapoor V, Baron RL, Peterson MS. Bile leaks after surgery. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:451–458. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.2.1820451. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.182.2.1820451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirao K, Miyazaki A, Fujimoto T, Isomoto I, Hayashi K. Evaluation of aberrant bile ducts before laparoscopic cholecystectomy: helical CT cholangiography versus MR cholangiography. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:713–720. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.3.1750713. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.175.3.1750713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner MA, Fulcher AS. The cystic duct: normal anatomy and disease processes. Radiographics. 2001;21:3–22. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja093. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon AH, Uetsuji S, Ogura T, Kamiyama Y. Spiral computed tomography scanning after intravenous infusion cholangiography for biliary duct anomalies. Am J Surg. 1997;174:396–401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9610(97)80050-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandio A, Javaid A, Mustafa S, Naqvi S, Aftab F. Biliary Tract Variations and its Correlation with Clinical Presentations. Surgery Curr Res. 2014;4:2161–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dusunceli E, Erden A, Erden I. Anatomic variations of the bile ducts: MRCP findings. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2004;10:296–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arrive L, Hodoul M, Arbache A, Slavikova-Boucher L, Menu Y, El Mouhadi S. Magnetic resonance cholangiography: Current and future perspectives. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39:659–664. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2015.07.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva AC, Friese JL, Hara AK, Liu PT. MR cholangiopancreatography: improved ductal distention with intravenous morphine administration. Radiographics. 2004;24:677–687. doi: 10.1148/rg.243035087. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/rg.243035087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwal S, Nag P, Sikora S, Prasad TL, Kumar S, Gupta RK. Fentanyl-augmented MRCP. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:582–587. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0155-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00261-005-0155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee NJ, Kim KW, Kim TK, et al. Secretin-stimulated MRCP. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:575–581. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0118-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00261-005-0118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]