Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to investigate the ability of the third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene to bind and act on CB2 cannabinoid receptor. We have identified, for the first time, that CB2 is a novel target for bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene. Our results showed that bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene were able to compete for specific [3H]CP-55,940 binding to CB2 in a concentration-dependent manner. Our data also demonstrated that by acting on CB2, bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene concentration-dependently enhanced forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation. Furthermore, bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene caused parallel, rightward shifts of the CP-55,940, HU-210, and WIN55,212-2 concentration-response curves without altering the efficacy of these cannabinoid agonists on CB2, which indicates that bazedoxifene- and lasofoxifene-induced CB2 antagonism is most likely competitive in nature. Our discovery that CB2 is a novel target for bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene suggests that these third-generation SERMs can potentially be repurposed for novel therapeutic indications for which CB2 is a target. In addition, identifying bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene as CB2 inverse agonists also provides important novel mechanisms of actions to explain the known therapeutic effects of these SERMs.

Keywords: cannabinoid receptor, inverse agonist, selective estrogen receptor modulator, bazedoxifene, lasofoxifene

1. Introduction

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) exhibit a unique pharmacological profile [1,2]. In contrast to estrogens, which are classified as agonists, and antiestrogens, which are classified as antagonists, SERMs are characterized by having estrogen agonist action in some tissues while acting as estrogen antagonists in others [1,2].

Based on the timing of their clinical development, SERMs can be divided into three generations: 1) Tamoxifen, a triphenylethlene, is considered a first generation SERM [1,2], 2) Raloxifene, a benzothiophene, is a member of second generation SERMs [1,2], 3) Third generation SERMs are typified by indole-based bazeoxifene [1,2,3] and napthalene derivative lasofoxifene [1,2,4].

Both first generation SERM tamoxifen and second generation SERM raloxifene have been approved by FDA to be used in the United States [1,2]. Tamoxifen is prescribed frequently for the prevention and treatment of breast cancer, and raloxifene is used mainly for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in post-menopausal women [1,2]. In 2009, third generation SERMs bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene were approved for use in the Europe to prevent and treat post-menopausal osteoporosis under the trade names Conbriza and Fablyn, respectively [1,2,3,4].

Cannabinoids exert their activity by activating cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) and cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2), which are two inhibitory G-protein-coupled receptors that were cloned and identified in the early 1990’s [5,6,7,8]. CB1 is expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral organs, whereas CB2 is primarily expressed in periphery tissues such as immune cells with limited distribution in the CNS [5,6,7,8]. Since CB2 receptor expression is minimal in the CNS, this receptor has emerged as a highly attractive therapeutic target, as CB2 ligands would, in theory, lack psychoactivity [7,8].

Because CB2 ligands have a wide range of therapeutic potentials, many novel agonists and antagonists for CB2 receptors have been synthesized and patented by pharmaceutical industry as well as academic laboratories [9,10]. However, bringing a new drug to market is a highly expensive and time consuming process which could cost anywhere from $500 million to $2 billion and could take 10 to 15 years [11,12]. In contrast, drug repurposing, i.e. discovering novel uses for marketed drugs outside of its original scope of indication, has emerged as a time, cost-effective, and low risk drug development approach [13,14]. The advantages of drug repurposing include: 1) Existing approval by regulatory agencies for human use, and 2) Existing human pharmacokinetic and safety data [13,14].

Previously, in an attempt to rapidly and efficiently identify drugs that may act as agonists or inverse agonists for CB2, we screened a library of 640 FDA-approved drugs using a validated high throughput cAMP assay [15]. Our efforts resulted in the identification of raloxifene (Evista), a second generation SERM, as a novel CB2 inverse agonist [15].

Our previous finding that raloxifene is an inverse agonist for the CB2 cannabinoid receptor prompted us to hypothesize that third-generation SERMs bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene may also act as inverse agonists for CB2. To test this hypothesis, in the current study, we investigated the actions of these two drugs on heterologously expressed human CB2 receptors, as well as the effects of these two drugs on the actions of known cannbinoids by conducting both competitive radioligand binding assays and cell-based cAMP accumulation assays.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate that bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene are inverse agonists for the CB2 cannabinoid receptor. Our findings indicate that these two marketed drugs can potentially be repurposed for novel therapeutic indications for which CB2 is a target. Our discovery that CB2 is a novel target for bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene suggests novel mechanisms of actions for these third-generation SERMs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles’s Medium (DMEM), penicillin/streptomycin, L-glutamine, trypsin, and geneticin were purchased from Mediatech (Manassas, VA). Fetal bovine serum was obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA). Glass tubes used for cAMP accumulation assays were obtained from Kimble Chase (Vineland, NJ). These tubes were silanized by exposure to dichlorodimethylsilane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) vapor for 3 h under vacuum. 384-well, round bottom, low volume white plates were purchased from Grenier Bio One (Monroe, NC). The cell-based HTRF cAMP HiRange assay kits were purchased from CisBio International (Bedford, MA). Forskolin was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Bazedoxifene was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Lasofoxifene was purchased from Toronto research Chemicals (Toronto, Ontario).

2.2. Cell Transfection and Culture

Human Embryonic Kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere consisting of 5% CO2, at 37°C. Expression plasmids containing the wildtype human cannabinoid receptors were stably transfected into HEK293 cells using lipofectamine, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Stably transfected cells were selected in culture medium containing 800 μg/ml geneticin. Having established cell lines stably expressing wildtype human CB2 receptors, the cells were maintained in growth medium containing 400 μg/ml of geneticin until needed for experiments.

2.3. Cell-based Homogenous Time Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF) cAMP assay

Cellular cAMP levels were measured using reagents supplied by Cisbio International (HTRF HiRange cAMP kit). Cultured cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (8.1 mM NaH2PO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 138 mM NaCl, and 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.2), and then dissociated in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1 mM EDTA. Dissociated cells were collected by centrifugation for 5 min at 2000g. The cells were resuspended in cell buffer (DMEM plus 0.2 % fatty acid free bovine serum albumin) and centrifuged a second time at 2000g for 5 min at 4°C. Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in an appropriate final volume of cell buffer plus the phosphodiesterase inhibitor Ro 20-1724 (2 μM). 5000 cells were added at 5μl per well into 384-well, round bottom, low volume white plates (Grenier Bio One, Monroe, NC). Compounds were diluted in drug buffer (DMEM plus 2.5 % fatty acid free bovine serum albumin) and added to the assay plate at 5 μl per well. Following incubation of cells with the drugs or vehicle for 7 minutes at room temperature, d2-conjugated cAMP and Europium cryptate-conjugated anti-cAMP antibody were added to the assay plate at 5 μl per well. After 2 hour incubation at room temperature, the plate was read on a TECAN GENious Pro microplate reader with excitation at 337 nm and emissions at 665 nm and 620 nm. To assess receptor antagonism, HEK293 cells stably expressing CB2 were pre-incubated for 20 min with vehicle (DMSO) or drug (bazedoxifene or lasofoxifene) at a concentration of 1 or 10 μM before subject to stimulation with cannabinoid agonists.

2.4. Cell harvesting and membrane preparation

Cells were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) consisting of 8.1 mM NaH2PO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.2, and scraped off the tissue culture plates. Subsequently, the cells were homogenized in membrane buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) with a Polytron homogenizer. After the homogenate was centrifuged at 46000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, the pellet was resuspended in membrane buffer and stored at −80 °C. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay using a BioRad protein reagent kit.

2.5. Ligand binding assays

The protocol for the equilibrium ligand binding assay can be found in our published papers [16,17,18,19] and are briefly described below. Drug dilutions were made in binding buffer (membrane buffer containing 0.5 mg/ml fatty acid free BSA) and then added to the assay tubes. [3H]CP55940 was used as a labeled ligand for competition binding assays for CB2. Binding assays were performed in 0.5 ml of binding buffer containing 0.1 mg/ml BSA for 60 min at 30° C. Membranes (80 μg) were incubated with [3H]CP55940 in siliconized culture tubes, with unlabeled ligands at various concentrations. Free and bound radioligands were separated by rapid ltration through GF/B lters (Whatman International, Florham Park, New Jersey, USA). The lters were washed three times with 3 ml of cold wash buffer (50 mmol/l Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, containing 1 mg/ml of BSA). The bound [3H]CP55940 was determined by liquid scintillation counting in 5 ml of CytoScint liquid scintillation uid (MP Biomedicals, Solon, Ohio, USA). The assays were performed in duplicate, and the results represent the averaged data from at least three independent experiments.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data analyses for cell-based HTRF cAMP assays were performed based on the ratio of uorescence intensity of each well at 620 nm and 665 nm. Data are expressed as delta F%, which is de ned as [(standard or sample ratio − ratio of the negative control)/ratio of the negative control] x 100. The standard curves were generated by plotting delta F% versus cAMP concentrations using non-linear least squares t (Prism software, GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Unknowns are determined from the standard curve as nanomolar concentrations of cAMP. After the unknowns are determined, the sigmoidal concentration-response equations were used (via Prism program, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) to generate the curves of the tested compounds. Data from ligand binding assays were analyzed, and competition binding curves were generated with the non-linear regression analyses using the Prism program.

3. Results

3.1. Competition of sepcific [3H]CP-55,940 binding by bazedoxifen and lasofoxifene

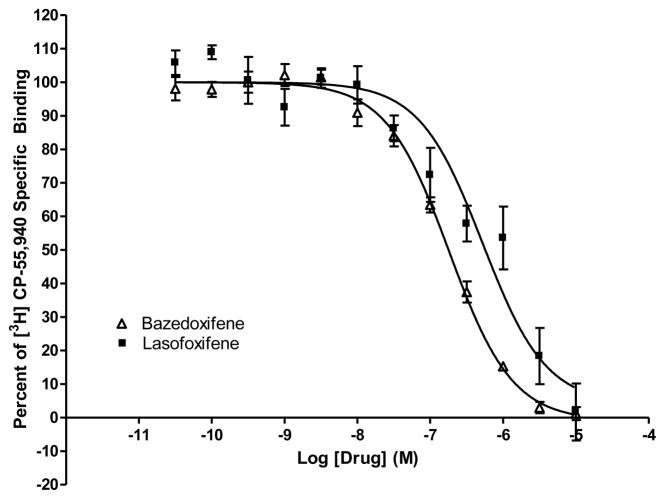

In order to investigate whether bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene bind to the CB2 receptor, we performed competition ligand binding experiments using membranes prepared from HEK293 cells stably expressing CB2. As shown in Fig. 1, bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene were able to compete for specific [3H]CP-55,940 binding in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, there was no detectable level of specific [3H]CP-55,940 binding in membranes prepared from HEK293 cells transfected with an empty vector (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene bind to the CB2 cannabinoid receptor.

Competition of specifc [3H]CP-55,940 binding by bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene. Bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene were used to compete for specific [3H] CP-55,940 binding to membranes prepared from HEK293 cells transfected with CB2. Data shown represent the mean ± SEM of three experiments performed in duplicate.

3.2. Effects of bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene on forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation

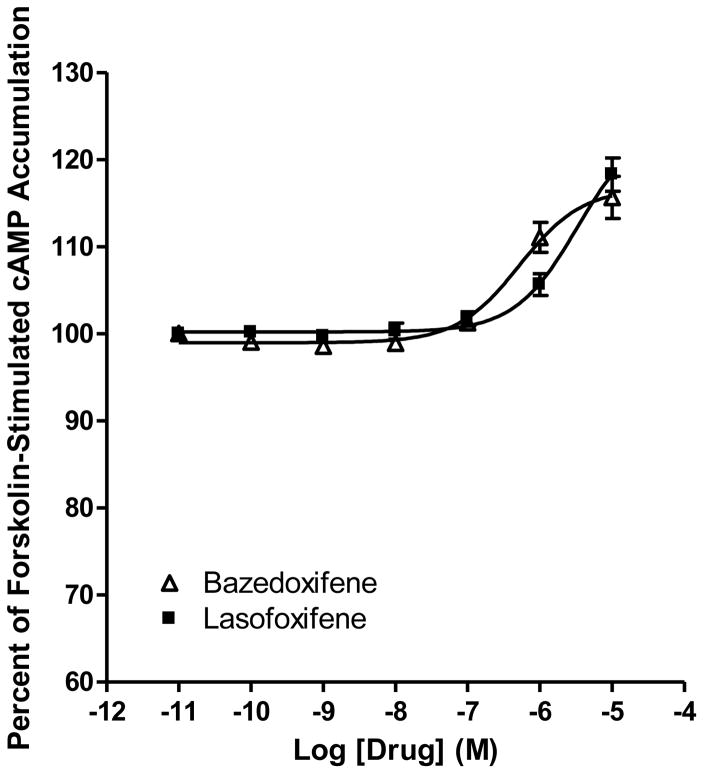

In order to investigate whether bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene act on the CB2 receptor, we performed cAMP accumulation assays using HEK293 cells stably expressing CB2. As shown in Fig. 2, we report for the first time that bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene behaved as inverse agonists for CB2 by enhancing forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation in a concentration-depenndent manner. Furthermore, bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene did not have any effects on forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation in empty vector- transfected HEK293 cells (data not shown).

Fig. 2. Bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene act on the CB2 cannabinoid receptor.

Effects of bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene on forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation. HEK293 cells stably expressing CB2 were treated with different concentrations of bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene for 7 minutes. Results are expressed as percent forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation. Data shown represent the mean ± SEM of five experiments.

3.3. Antagonism of cannabinoid agonist-induced inhibition forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation by bazedoxifene

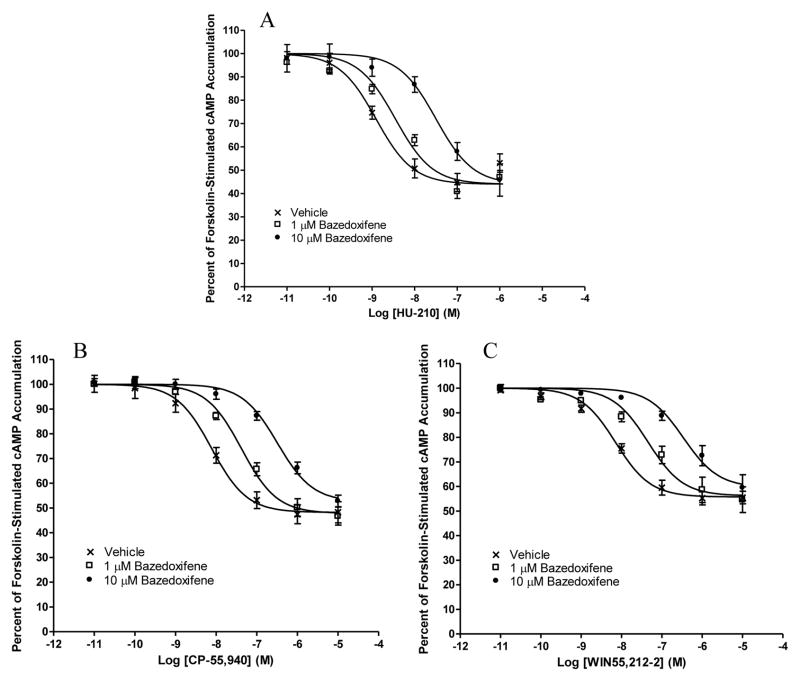

As shown in Fig. 3A–C, in HEK293 cells stably expressing CB2, the cannabinoid agonists CP-55,940, HU-210, and WIN55,212–2 concentration-dependently inhibited forskolin-stimulated cAMP production. Most importantly, in a concentration-dependent manner, 1 and 10 μM bazedoxifene pretreatments resulted in a rightward, parallel shift of the concentration-response curves for the three cannabinoid agonists (Fig. 3A–C).

Fig. 3. Antagonism of cannabinoid agonist-induced inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation by bazedoxifene.

HEK293 cells stably expressing CB2 were pre-incubated for 20 min with vehicle or bazedoxifene at a concentration of 1 or 10 μM before subject to stimulation with cannabinoid agonists (A) HU-210, (B) CP-55,940, and (C) WIN55,212–2 for 7 min. Results are expressed as percent forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation. Data shown represent the mean ± SEM of five experiments.

3.4. Antagonism of cannabinoid agonist-induced inhibition forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation by lasofoxifene

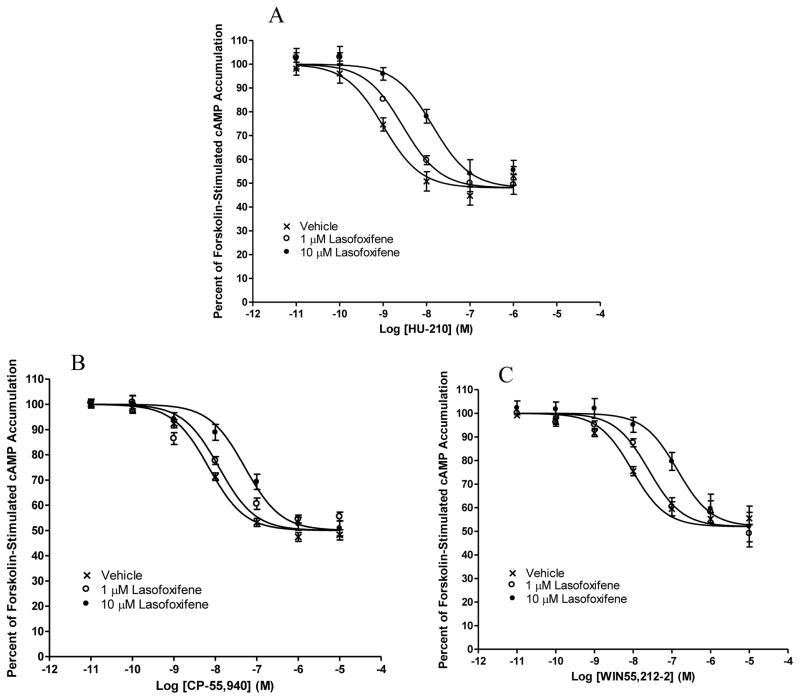

As shown in Fig. 4A–C, in HEK293 cells stably expressing CB2, in a concentration-dependent manner, pretreatment with lasofoxifene at a concentration of 1 and 10 μM resulted in a rightward, parallel shift of the concentration-response curves for three cannabinoid agonists CP-55, 940, HU-210, and WIN55,212–2.

Fig. 4. Antagonism of cannabinoid agonist-induced inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation by lasofoxifene.

HEK293 cells stably expressing CB2 were pre-incubated for 20 min with vehicle or lasofoxifene at a concentration of 1 or 10 μM before subject to stimulation with cannabinoid agonists (A) HU-210, (B) CP-55,940, and (C) WIN55,212–2 for 7 min. Results are expressed as percent forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation. Data shown represent the mean ± SEM of five experiments.

4. Discussion

Previously, in an attempt to identify novel ligands for CB2, we screened a library of 640 FDA-approved drugs using a cell-based HTRF assay for measuring changes in intracellular cAMP [15]. Our efforts resulted in the identification of raloxifene, a second generation SERM used to treat/prevent post-menopausal osteoporosis, as a novel CB2 inverse agonist [15]. In this article, we report for the first time that CB2 is a novel target for third-generation SERMs bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene.

In the current study, bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene were able to compete, in a concentration-dependent manner, for specific [3H]CP-55,940 binding to CB2. Analysis of the competition curves revealed that the rank order of affinity of these SERMs for CB2 was bazedoxifene > lasofoxifene. These data demonstrate that these two drugs were able to bind specifically to the CB2 cannabinoid receptor.

In this study, bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene enhanced cAMP accumulation concentration-dependently in HEK293 cells stably expressing CB2. The rank order of potency of these two drugs in enhancing cAMP accumulation was found to be bazedoxifene > lasofoxifene. Since these two drugs did not have any effect on forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation in empty vector-transfected HEK293 cells, our data show that the effect of bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene on cAMP accumulation was mediated through CB2 receptor.

To further characterize the pharmacological properties of these two drugs on CB2, we evaluated their ability to antagonize the effects of three cannabinoid agonists. Bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene concentration-dependently caused rightward shifts of the CP-55,940, HU-210, and WIN55,212-2 concentration-response curves. Our data indicate that the mode of CB2 antagonism induced by bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene is most likely competitive in nature, as these rightward shifts were parallel and were not associated with any change in the Emax of cannabinoid agonists.

Estrogen deficiency is the main cause of post-menopausal osteoporosis. When estrogen is deficient, bone turnover increases, and bone resorption increases more than bone formation, leading to bone loss [1,2,3,4]. Bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene belong to the classes of SERMs, which exhibit estrogen agonist activity in some target tissues while exert estrogen antagonist activity in other tissues [1,2,3,4]. Both are estrogen agonists in the bone and have been approved for the treatment and prevention of post-menopausal osteoporosis in Europe [1,2,3,4].

The effects of bazedoxifene on bone have been investigated in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis in a large phase III clinical trial [20]. Compared to placebo, bazedoxifene at a dose 20 mg or 40 mg per day significantly reduced the risk of new vertebral fractures [20]. Furthermore, compared to placebo, bazedoxifene significantly improved bone mineral density [20].

The effects of lasofoxifene on bone have been investigated in great detail and are well established [21]. A large clinical trial, the Postmenopausal Evaluation and Risk-Reduction with Lasofoxifene (PEARL), was conducted in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis. Lasofoxifene at a dose of 0.5 mg per day was associated with reduced risks of nonvertebral and vertebral fractures [21]. Furthermore, lasofoxifene improved bone mineral density compared to placebo group [21].

The pharmacological actions of bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene are known to be mediated through binding to estrogen receptors [1,2,3,4]. This binding results in activation of estrogenic pathways in certain tissues such as bone, and blockade of estrogen pathways in other tissues such as breast [1,2,3,4]. Bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene are well known for their SERM properties. However, to our knowledge, this report is the first time that bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene have been demonstrated to behave as inverse agonists for CB2. Cannabinoids and their receptors play important roles in bone metabolism by regulating bone cell function [22]. It has been shown that the CB2 inverse agonist SR144528 can reduce bone loss by inhibiting osteoclast formation and bone resorption [22]. Therefore, our new discovery that bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene are CB2 inverse agonists implicates a novel mechanism for the anti-osteoporosis activity of these third-generation SERMs—the effects might be partially mediated through the CB2 cannabinoid receptor in the bone.

Recently, there is accumulating evidence to suggest that CB2 inverse agonists are effective for controlling inflammatory cell migration, thus are useful for a variety of inflammatory diseases, such as arthritis and multiple sclerosis [23]. Therefore, our identification of bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene as a novel CB2 inverse agonist suggests that these third-generation SERMs have great potential to be repurposed for other therapeutic indications for which CB2 is a target.

In summary, we have identified bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene, two third-generation SERMs, as novel CB2 inverse agonists. These new findings provide novel mechanisms of action to explain the known therapeutic effects of these two marketed drugs. Our discovery also suggests that bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene can potentially be repurposed for novel therapeutic indications for which CB2 is a target.

Highlights.

CB2 was discovered to be a novel target for bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene

Bazdoxifene and lasofoxifene behaved as novel CB2 inverse agonists

Our discovery provides insights into repurposing bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene

Our data suggests new mechanisms of actions for bazedoxifene and lasofoxifene

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grants EY13632 and DA11551.

Abbreviations

- SERM

selective estrogen receptor modulator

- CB1

cannabinoid receptor 1

- CB2

cannabinoid receptor 2

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- FDA

food and drug administration

- HTRF

homogenous time resolved fluorescence

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Riggs BL, Hartmann LC. Selective estrogen-receptor modulators -- mechanisms of action and application to clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:618–629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maximov PY, Lee TM, Jordan VC. The discovery and development of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for clinical practice. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2013;8:135–155. doi: 10.2174/1574884711308020006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stump AL, Kelley KW, Wensel TM. Bazedoxifene: a third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulator for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:833–839. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gennari L, Merlotti D, Martini G, Nuti R. Lasofoxifene: a third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulator for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:1091–1103. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.9.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howlett AC. Cannabinoid receptor signaling. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005:53–79. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26573-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pertwee RG. Pharmacological actions of cannabinoids. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005:1–51. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26573-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riether D. Selective cannabinoid receptor 2 modulators: a patent review 2009--present. Expert opinion on therapeutic patents. 2012;22:495–510. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.682570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marriott KS, Huffman JW. Recent advances in the development of selective ligands for the cannabinoid CB(2) receptor. Current topics in medicinal chemistry. 2008;8:187–204. doi: 10.2174/156802608783498014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams CP, Brantner VV. Estimating the cost of new drug development: is it really 802 million dollars? Health affairs. 2006;25:420–428. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. Journal of health economics. 2003;22:151–185. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carley DW. Drug repurposing: identify, develop and commercialize new uses for existing or abandoned drugs. Part II. IDrugs : the investigational drugs journal. 2005;8:310–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carley DW. Drug repurposing: identify, develop and commercialize new uses for existing or abandoned drugs. Part I. IDrugs : the investigational drugs journal. 2005;8:306–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar P, Song ZH. Identification of raloxifene as a novel CB2 inverse agonist. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013;435:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng W, Song ZH. Effects of D3.49A, R3.50A, and A6.34E mutations on ligand binding and activation of the cannabinoid-2 (CB2) receptor. Biochemical pharmacology. 2003;65:1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nebane NM, Kellie B, Song ZH. The effects of charge-neutralizing mutation D6.30N on the functions of CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors. FEBS letters. 2006;580:5392–5398. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song ZH, Feng W. Absence of a conserved proline and presence of a conserved tyrosine in the CB2 cannabinoid receptor are crucial for its function. FEBS letters. 2002;531:290–294. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song ZH, Slowey CA, Hurst DP, Reggio PH. The difference between the CB(1) and CB(2) cannabinoid receptors at position 5.46 is crucial for the selectivity of WIN55212-2 for CB(2) Molecular pharmacology. 1999;56:834–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverman SL, Christiansen C, Genant HK, Vukicevic S, Zanchetta JR, de Villiers TJ, Constantine GD, Chines AA. Efficacy of bazedoxifene in reducing new vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from a 3-year, randomized, placebo-, and active-controlled clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1923–1934. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings SR, Ensrud K, Delmas PD, LaCroix AZ, Vukicevic S, Reid DM, Goldstein S, Sriram U, Lee A, Thompson J, Armstrong RA, Thompson DD, Powles T, Zanchetta J, Kendler D, Neven P, Eastell R. Lasofoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:686–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Idris AI, Sophocleous A, Landao-Bassonga E, van’t Hof RJ, Ralston SH. Regulation of bone mass, osteoclast function, and ovariectomy-induced bone loss by the type 2 cannabinoid receptor. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5619–5626. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lunn CA, Reich EP, Fine JS, Lavey B, Kozlowski JA, Hipkin RW, Lundell DJ, Bober L. Biology and therapeutic potential of cannabinoid CB2 receptor inverse agonists. British journal of pharmacology. 2008;153:226–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]