Abstract

Background

Over recent years genetic testing for germline mutations in BRCA1/BRCA2 has become more readily available because of technological advances and reducing costs.

Objective

To explore the feasibility and acceptability of offering genetic testing to all women recently diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC).

Methods

Between 1 July 2013 and 30 June 2015 women newly diagnosed with EOC were recruited through six sites in East Anglia, UK into the Genetic Testing in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer (GTEOC) study. Eligibility was irrespective of patient age and family history of cancer. The psychosocial arm of the study used self-report, psychometrically validated questionnaires (Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21); Impact of Event Scale (IES)) and cost analysis was performed.

Results

232 women were recruited and 18 mutations were detected (12 in BRCA1, 6 in BRCA2), giving a mutation yield of 8%, which increased to 12% in unselected women aged <70 years (17/146) but was only 1% in unselected women aged ≥70 years (1/86). IES and DASS-21 scores in response to genetic testing were significantly lower than equivalent scores in response to cancer diagnosis (p<0.001). Correlation tests indicated that although older age is a protective factor against any traumatic impacts of genetic testing, no significant correlation exists between age and distress outcomes.

Conclusions

The mutation yield in unselected women diagnosed with EOC from a heterogeneous population with no founder mutations was 8% in all ages and 12% in women under 70. Unselected genetic testing in women with EOC was acceptable to patients and is potentially less resource-intensive than current standard practice.

Keywords: Clinical genetics, Genetic screening/counselling, Obstetrics and Gynaecology

Introduction

Approximately 1.5% of women will be diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) in their lifetime and, as a result of the relatively poor prognosis, it is the fifth commonest cause of cancer-related mortality in women. In the mid-1990s germline mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes were identified in families with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer and testing for these genes is available through the NHS genetic service if the family history is sufficiently strong to instigate a referral (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline CG41). A woman with a mutation in the BRCA1 gene has a 40–60% lifetime risk of developing EOC.1 For BRCA2 the lifetime risk is lower at 10–30%, but this is still around a 10-fold higher risk than for the general population. At present there is no proven clinical screening for EOC2 and unaffected women with completed families who carry BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations typically elect to have a prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy that reduces the risk of EOC by 80–96%.3–5 The prevalence of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in unselected women with ovarian cancers ranges from 8% to 22%,6–10 and this variation can in part be explained by the presence or absence of founder mutations in the study populations. In one study of 1342 unselected patients with invasive ovarian cancer, 161 BRCA1/BRCA2 carriers were identified in 1038 women diagnosed with high-grade serous or endometrioid ovarian cancer (overall frequency 15.5%), confirming that inherited mutations in these genes account for a significant minority of all ovarian cancer cases.9 The frequency of mutations was highest in the high-grade serous ovarian cancer group (135 carriers, 18%) but also significant in women with endometrioid OC (26 carriers, 9%). Family history of breast or ovarian cancer was the best predictor of carrier status (33% had a first-degree relative with breast or ovarian cancer) but 7.9% of all carriers had no significant family history.

Genetic testing for mutations in BRCA1/BRCA2 was introduced into clinical practice in the late 1990s but because of the cost and technical complexity of testing it was initially limited to those cases where there was a >20% probability of detecting a mutation (NICE guideline CG41), with the threshold being lowered to 10% probability since 2013 (NICE guideline CG164). Various models, such as BOADICEA11 and the Manchester score,12 have been developed to estimate the probability of finding a BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation. Although these are extensively used in clinical genetics centres, they have in general not been incorporated into routine clinical practice elsewhere. Despite increasing awareness of BRCA1/BRCA2 in the medical community, referral rates vary considerably and many women are not referred for a genetic assessment; only 20% of the cohort studied by Zhang et al9 had previously been referred for genetic testing13 and as the referred group contained only 60% of all mutation carriers, 40% of mutation carriers were missed. If more mutation carriers could be identified this would increase the numbers of families for whom cascade genetic testing could be offered so that more female relatives at high risk of EOC and breast cancer could be identified, counselled and managed appropriately.

BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers with EOC have a better short-term survival than non-BRCA1/BRCA2 women14 and emerging evidence suggests that BRCA2 mutation status, in particular, is likely to be an important prognostic and predictive marker in EOC with a significantly higher primary chemotherapy sensitivity rate,14 15 although the survival difference becomes less apparent over time.16 It also appears that BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation status provides predictive information about the likelihood of response to poly(adenosine diphosphate ribose) polymerase inhibitors.17 18

In this study we explored the acceptability and feasibility of universal testing, without pre-test genetic counselling, for BRCA1/BRCA2 in an unselected population of women who were within 12 months of being diagnosed with EOC. We used established metrics (the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and the Impact of Event Scale (IES)) to assess psychological distress, tailored questionnaires to gauge acceptability and undertook a detailed cost analysis to compare resource use with the standard genetic testing model.

Patients and methods

Patient eligibility

Patients were eligible if they were aged >18 years and had been diagnosed with high-grade serous or endometrioid EOC within the past 12 months. Other ovarian cancer subtypes, including low-grade tumours, were excluded as they are not part of the BRCA1/BRCA2 phenotype.9 The study had full ethical approval (REC12/EE/0433).

Patient recruitment

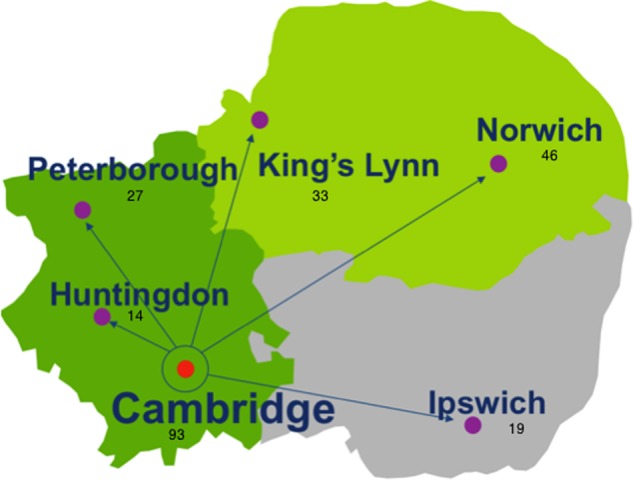

Women were recruited though six NHS hospitals of different sizes, ranging from smaller district general hospitals to large regional centres (figure 1). All women with ovarian cancer in the East Anglia region are managed in these six institutions, which allows for near-complete ascertainment of cases. Eligible women were approached by their treating clinician or specialist nurse. If the patient expressed interest in the study, the study coordinator was informed and provided the patient with detailed information about the study and obtained informed consent. Additionally, a letter was sent to the patient to collect her demographic details and family history (figure 2). No formal genetic counselling was given before testing.

Figure 1.

The location of hospitals in the Anglia region and number of patients recruited at each site.

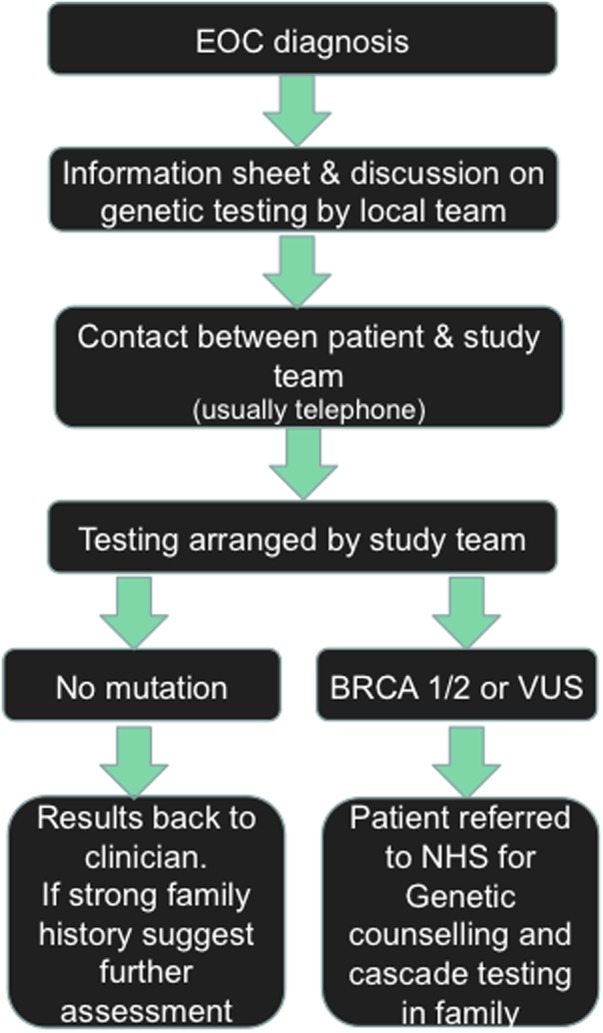

Figure 2.

The Genetic Testing in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer (GTEOC) protocol. VUS, variants of unknown significance.

Genetic counselling and testing process

BRCA1/BRCA2 testing was performed in the clinically accredited laboratory of the East Anglian Genetics Service by next-generation sequencing and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. If a gene mutation was identified the patient, her general practitioner and her treating clinician were informed by a letter from the study team, and a referral to the NHS clinical genetics service was requested for genetic counselling and cascade testing of other at-risk family members. Where variants of unknown significance (VUS) were identified these were also fed back to the participant, general practitioner and her clinician by letter, and again a referral for genetic counselling was requested (figure 2). Only those women with mutations or VUS received formal post-test genetic counselling via the standard clinical service. All family histories were assessed by a geneticist when the mutation report was generated. If there was a clinically relevant family history that met standard referral criteria in women with no mutations this was noted in the results letter to the participant with advice to seek a genetics referral.

Cost analysis

In order to determine the resource implications of offering universal BRCA1/BRCA2 testing in an unselected population of women within 12 months of being diagnosed with EOC we undertook a cost analysis. We mapped both the existing (current standard) referral and testing pathway (see online supplementary figure S1) and the new proposed referral and testing pathway (see online supplementary figure S2). Once these pathways were mapped, we defined the service activities and determined the resources required to undertake these activities using a ‘bottom-up’ micro-costing approach in order to calculate the overall cost for both pathways. Costs are reported in 2015 UK pounds and from the perspective of the clinical genetics service from referral for genetic testing to diagnostic BRCA1/BRCA2 test outcome of the index case. Market prices taken from the NHS test directory hosted on the UKGTN website (http://ukgtn.nhs.uk) were used for the actual genetic testing of BRCA1/BRCA2. The cost of staff (administrators and clinical staff) was obtained from both the NHS agenda for change (2015) and the Personal Social Services Research Unit reference costs for 2014/2015. We used the mid-point of each grade and included national insurance, superannuation and overhead costs if they were not already included. All cost data collected are reported in online supplementary table S1. Here we report the average testing pathway cost for each BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation identified, the average testing pathway cost for each genetic test offered and the overall budget required for the 232 patients with EOC eligible for inclusion within the Genetic Testing in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer (GTEOC) study.

jmedgenet-2016-103902supp.pdf (242.2KB, pdf)

The main (base case) analysis assumes that in addition to those meeting the Manchester score for genetic testing (n=63 of the 232 patients with EOC), half (50%) of those affected by EOC were also referred through to the cancer genetics service to have their family history checked before determining whether they would have genetic testing. The base-case analysis does not have an age cut-off point and no discount rate has been applied given that all patients would expect to receive the result of their genetic test within a year.

Cost analysis sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses allow insight into which assumptions or limitations to the data included are important to the overall result or conclusion drawn from the analysis. A pragmatic approach to conducting one-way sensitivity analyses was undertaken and included varying the cost of the genetic test (assay price in both pathways), varying the percentage of patients referred to the clinical genetics service in the existing current testing pathway (from 0% of patients not meeting the Manchester score to 100%—ie, all patients offered initial appointment in clinical genetics service) and limiting the genetic testing within the GTEOC testing pathway to women aged <70 years.

Psychological impact and acceptability analysis

All participants who underwent genetic testing were asked to complete a short, self-report questionnaire that was sent to them by post to limit intrusion. This included the DASS-2119 and the IES.20 Each scale was presented twice: once anchored to the psychological impact of diagnosis of ovarian cancer, and a second time anchored to the psychological impact of the genetic test. A further 12 study-specific questions assessed the acceptability of this method of genetic testing.

Results

A total of 232 of 281 eligible women (83%) consented to participate and be tested over the study period. Almost all (97%) participants reported their ethnicity as white British, in keeping with the demographic profile of the region (table 1). The mean age of the participants was 63 years (range 28–89 years) and two-thirds of the participants were ≥60 years, which is consistent with the observed age profile in women diagnosed with EOC. One hundred and ninety-one participants (82%) had HGSOC, 20 (9%) had endometrioid OC, 15 (6%) had unspecified or poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas and 6 (2.5%) were mixed types. The median time from consent to results delivered was 46 working days (range 15–117 days) and from sample receipt to results delivered was 39 working days (range 11–111 days). Overall, 175 women (75%) had stage III or IV disease. Educational levels were available for 166 participants (72%) and in this group of women 100 (60%) had completed secondary education only, 37 (22%) had completed a diploma and 25 (15%) were educated to degree level (table 1).

Table 1.

Study population demographics

| Demographic | n |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (range) | 63 (28–89) |

| Country of birth, n (%) | |

| UK | 224 (97) |

| Other | 8 (3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 226 (98) |

| Other | 6 (2) |

| Pathology, n | |

| Serous | 192 |

| Endometrioid | 20 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 15 |

| Mixed | 5 |

| Stage, n | |

| I | 34 |

| II | 6 |

| III | 133 |

| IV | 42 |

| Not classified | 17 |

| Educational status (total n=166), n (%) | |

| Degree | 26 (15) |

| Diploma | 38 (22) |

| Secondary | 100 (60) |

| Primary | 2 (1) |

Eighteen BRCA1/BRCA2 predicted loss-of-function mutations were detected (12 in BRCA1, six in BRCA2), giving an overall prevalence of 8% (table 2). None of the mutations were common founder mutations seen in other populations (see online supplementary table S2).21 The mean age of mutation carriers was 49.5 years (range 40–75 years) with a mutation prevalence of 12% in women aged <70 years (17/146) and 1% in unselected women aged ≥70 (1/86).

Table 2.

Age at diagnosis and pathology characteristics of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers

| BRCA1/2+ (n=18) | BRCA1/2 VUS (n=15) | Non-BRCA1/2 (n=199) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (range) | 49.5 (40–75) | 64.8 (41–84) | 66.1 (28–89) |

| BRCA1, n (%) | 12 (67) | 3 (20) | N/A |

| BRCA2, n (%) | 6 (33) | 12 (80) | N/A |

| Pathology, n | |||

| High-grade serous | 15 | 11 | 166 |

| Endometrioid | 1 | 4 | 15 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 2 | 0 | 13 |

| Mixed types | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Stage, n | |||

| I | 4 | 5 | 25 |

| II | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| III | 12 | 9 | 112 |

| IV | 2 | 1 | 39 |

| Not classified | 0 | 0 | 15 |

VUS, variants of unknown significance.

In women less than 70 years of age with a positive family history (affected first- or second-degree relative) the mutation prevalence was 17% (13/77), but one-quarter of the mutation carriers in this age group had no family history. Six mutation carriers had a previous personal history of breast cancer (table 2). All 12 BRCA1 and five of the BRCA2 mutation-positive cases had high-grade serous ovarian cancer (table 2). The other BRCA2-mutation positive case had a high-grade adenocarcinoma with features suggestive of an endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Seventeen VUS were detected in 15 patients, 14 in BRCA1 and three in BRCA2.

Psychological impact

One hundred and seventy-three questionnaires were returned (75%). IES (cognitive intrusion—ie, unwanted intrusive thoughts about the phenomenon; avoidance behavior; hyperarousal—ie, a state of increased psychological and physiological tension) and DASS-21 (depression, anxiety and stress) scores in response to genetic testing were significantly lower than equivalent scores in response to cancer diagnosis (Wilcoxon signed rank tests Z score range=−6.174 to −8.852; all p<0.001). Essentially, having the genetic test did not increase distress or psychological traumatic response beyond that already being experienced as a result of the cancer diagnosis itself. Younger participants found that the test led to more intrusive thoughts (IES intrusion r=−0.172, p=0.026) and significantly more stress (DASS stress r=0.162, p=0.014). There were no significant differences based on age for IES avoidance, IES hyperarousal, DASS anxiety or DASS depression. There were no significant differences on any IES or DASS subscale according to educational level, cancer stage, Manchester score or previous cancer history. A significant difference was found in cognitive avoidance scores based on categorisation of BRCA mutation status (p=0.036), with highest mean scores reported by those with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. The study population was not sufficiently heterogeneous to explore any differences based on either ethnicity or country of birth.

Acceptability of the test

High levels of acceptability were reported (table 3) and participants felt they had enough information and time to proceed with genetic testing. Most women talked to their family about the test and felt that the test gave them a better understanding of their family's risk. The widest variation in scores related to the perceived level of ease with which participants made the decision to proceed with genetic testing.

Table 3.

Quantitative analysis of acceptability using 13 tailored questions

| Question | n | Mean score | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1: I was pleased to have the option of genetic testing | 173 | 5.72 | 0.846 |

| High mean score=pleased to have option of genetic test | |||

| Q2: I had access to enough information to make a decision about testing | 174 | 5.61 | 0.953 |

| High mean score=had enough information to make decision | |||

| Q3: It was difficult to decide whether to have the genetic test | 172 | 2.05 | 1.80 |

| Low mean score=easy to make decision | |||

| Q4: I had enough time to think about whether to have the genetic test | 174 | 5.43 | 1.29 |

| High mean score=had enough time to make decision | |||

| Q5: I found genetic testing to be useful to me | 172 | 5.49 | 1.07 |

| High mean score=genetic test was useful | |||

| Q6: I was reassured by my genetic test results | 173 | 5.30 | 1.30 |

| High mean score=reassured by test results | |||

| Q7: The genetic test results allowed me to better understand my cancer risks | 173 | 5.00 | 1.48 |

| High mean score=test allowed better understanding of cancer risks | |||

| Q8: The genetic test results allowed me to better understand my family's cancer risks | 173 | 5.31 | 1.26 |

| High mean score=test allowed better understanding of family's risk | |||

| Q9: This was a good time for me to have the genetic test | 171 | 5.43 | 1.19 |

| High mean score=good time to have test | |||

| Q10: I would have preferred to wait before I had genetic testing | 171 | 1.49 | 1.21 |

| Low mean score=wouldn't have wanted to wait before test | |||

| Q11: I found genetic testing to be stressful | 170 | 1.75 | 1.53 |

| Low mean score=didn't find it stressful | |||

| Q12: I was satisfied with the support I received from family and friends | 168 | 5.52 | 1.13 |

| High mean score=satisfied with family/friend support | |||

| Q13: I talked to my family about my genetic test | 169 | 5.73 | 1.15 |

| High mean score=most talked to their family about the test |

Possible score range was 1.0 (min) to 6.0 (max).

Cost analysis

For the base-case analysis, the overall budget, the average patient pathway cost for each BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation positive and the average patient pathway cost for each test offered for the current pathway were £142 702, £11 892, and £2265, respectively. For the GTEOC patient pathway, these costs were £253 617, £14 919 and £1093, respectively (see online supplementary table S2). The larger budget for the GTEOC patient pathway represents the increased cost due to the significantly greater number of genetic tests undertaken. When the cost of the genetic testing is removed from the cost of the patient pathway, the budget for GTEOC patient pathway is lower than for the current patient pathway (£56 166 vs £88 633). The non-genetic test-related costs within the GTEOC patient pathway account for about 22% of the budget compared with 62% for the current patient pathway within the base-case analysis. The average patient pathway cost for each patient without the genetic testing for the GTEOC and the current testing patient pathway are £243 and £383, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis

The results of the sensitivity analysis show that changing the cost of the genetic test has a large effect on the budget, the average patient pathway cost for each BRCA1/BRCA2 positive and also the average testing pathway cost for each test offered for both pathways (see online supplementary table S3). If the cost of the genetic test were reduced to £190, the budget required for the GTEOC pathway would be the same as the current pathway, with other conditions remaining the same, as in the base-case analysis. Changing the number of women referred to the clinical genetics service affects the budget required for the existing pathway. Implementing the age cut-off point of 70 years for eligibility of genetic testing in the GTEOC pathway has a large effect on the budget required to test the 232 eligible women. Even with a genetic test price of £650 (the current price of a clinical exome), implementing the age cut-off point within the GTEOC patient pathway would lead to a lower budget for the GTEOC pathway (£121 229 vs £130 102 for the current patient pathway).

Discussion and conclusions

The primary objective of the study was to determine the feasibility, acceptability and cost-effectiveness of screening all newly diagnosed women with EOC for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations by determining the mutation prevalence, calculating the cost for each gene mutation detected and assessing the psychological impact based on questionnaire responses and qualitative interviews.

The mutation prevalence in an unselected cohort of women diagnosed with EOC from a heterogeneous population with no founder mutations was 8% in all ages and 12% in women aged <70 years. This is similar to that reported in a combined study of two large case–control OC series (one of which included cases from the East Anglia region),8 but lower than the frequency of 15% reported in a recent study by Norquist et al.10 These differences are likely to be partly explained by the presence or absence of founder mutations in the test populations as 13% of all the BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations identified in the Norquist study were those commonly found in individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.

The cost analysis undertaken here provides some insight into the potential delivery of BRCA1/BRCA2 genetic testing in a cohort of women diagnosed with EOC. The burden of cost in the provision of genetic testing lies in the provision of diagnostic testing for the current patient pathway (62% of costs are non-genetic test related), whereas with the GTEOC pathway the burden lies in the cost of the genetic testing itself (only 22% of costs were non-genetic test related). Furthermore, a high price of genetic testing was used for the base case, and when a more realistic current day price is included in a sensitivity analysis, coupled with an age cut-off point, the GTEOC patient testing pathway is probably cost saving compared with the current testing pathway for this patient cohort. However, a clear limitation of this analysis is the exclusion of the costs involved in the clinical management of these patients, which are likely to be significant when cascade testing is also included in the ‘patient’ pathway.

Based on our findings we would recommend offering testing to all women with EOC aged <70 years as the mutation prevalence would be above the current threshold of 10% used for eligibility for testing breast cancer families in the UK (NICE CG164). This age cut-off point would also improve the mutation:VUS ratio from 1:1 to 2:1. By not testing those aged ≥70 years it is possible to reduce the number of tests by around 37% and miss only 6% of all mutations. Indeed, in this study the woman over the age of 70 with a mutation had a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. No mutation carriers would have been missed using the criteria: (1) age <70 years, or (2) ≥70 years with a previous history of breast cancer or history of breast or ovarian cancer in a first-degree relative.

A key question of the GTEOC study was whether outcome of the genetic test affects IES or DASS-21 scores. Our study investigated the hypothesis that psychological response to the genetic test might lead to increased distress beyond that of the cancer diagnosis itself. Methodologically, this was difficult to test and we used the approach of including each psychological measure twice (with different anchoring) to allow participants to distinguish their psychological responses to the genetic test from their psychological response to the cancer diagnosis itself. Participants responded differently to identical questions anchored to each event, suggesting that this is a useful methodology; mean ratings on all subscales of both the IES and the DASS were significantly higher for cancer diagnosis than for the genetic test, consistent with previous findings in patients with breast cancer.22 We also investigated whether the psychological response to the genetic test would be affected by participant demographics. Correlation analyses indicated no significant effects of age on depression, anxiety cognitive avoidance or hyperarousal; significant negative correlations indicate an inverse relationship between younger age and higher levels of perceived stress and cognitive intrusion. This result fits the pattern of broader literature on the psychological impact of cancer diagnosis and treatment, whereby adjustment is typically worse in those diagnosed at a younger age.23 Those later found to have a genetic mutation scored significantly higher on cognitive avoidance, but no differences in other subscales assessed were identified. Self-reported acceptability data were favourable and support the value and acceptability of the testing procedure in this sample.

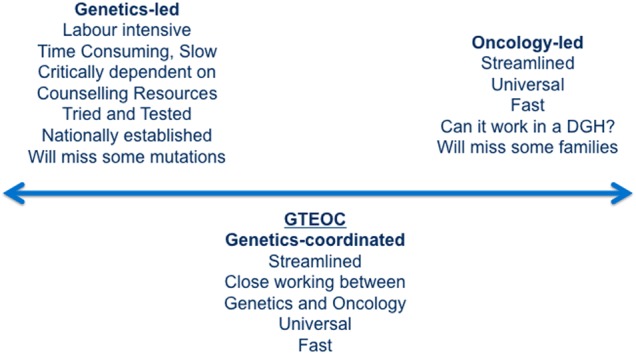

Genetic counselling protocols have evolved from a paradigm initially developed for predictive testing of Huntington's disease (HD). Owing to concerns about the negative and potentially grave impact of receiving a molecular diagnosis of HD, a protocol involving two face-to-face pre-test appointments and follow-up was developed.24 It has long been thought that this level of support may not be required in the diagnostic setting25 and with the advent of targeted treatments the need for systematic genetic testing has become more pressing, but current pathways are not designed for high-volume testing. One solution would be to devolve genetic testing completely to the oncologists but this approach fails to take advantage of the comprehensive clinical genetic networks that exist in many countries. There are also other concerns about this approach; the interpretation of VUS may not be adequate,26 and cascade testing within families may not occur (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Models of service delivery for genetic testing. DGH, district general hospital; GTEOC, Genetic Testing in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer study.

A unique strength of this study is the near-complete ascertainment of women with ovarian cancer recruited through both secondary and tertiary referral centres in a clearly defined geographical region which is highly representative of clinical services throughout the UK and internationally. These findings are therefore likely to be widely applicable, and similar new approaches have been trialled in other countries, such as Norway7 and the Netherlands.27 Even though overall numbers tested are relatively small, the participation rate was high and the mutation yield is consistent with those reported in other studies in heterogeneous populations lacking founder mutations. One weakness is the lack of ethnic diversity in the study participants, which reflects the relative homogeneity of the East Anglian population (91% white Caucasian for all ages; Office for National Statistics, 2011 Census data from KS201EW). Further studies would be required to assess acceptability in more ethnically diverse regions.

These results show that universal genetic testing in women with a diagnosis of EOC is an acceptable and sensitive procedure: these women have to deal with great emotion as they confront their diagnosis, mortality and the impact on family members. Our data show that this type of genetic testing does not increase distress or traumatic response significantly beyond that already experienced after a diagnosis of cancer. Older age was a protective factor against traumatic response, but not distress. Comprehensive case-based genetic testing appears to be acceptable to patients and is less resource-intensive than standard current practice where all women are referred for genetic counselling before testing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Simon Newman and the Target Ovarian Cancer team for their help, advice and comments throughout the study. We would like to thank all the study participants and their clinicians.

Footnotes

Contributors: MT, JB, PP and RC conceived the idea, developed the study protocol and oversaw the project. IP and HS coordinated the running of the study. JD, ET and StAb coordinated the mutation analysis. HS and NH-W performed the psychosocial analysis, VB and GS performed the health economic analysis, MJ-L performed the pathological review. BN, CH, EB, PR, RN, SM, AD, VL, HW, LTT, MD, SaAy, BR, HE, CP and TD assisted with the recruitment of study participants. MT drafted the manuscript and all authors read and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by Target Ovarian Cancer grant number T005MT. GS was supported by funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre. MT was supported by funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Program (2007Y2013)/European Research Council (Grant No. 310018).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: National Research Ethics Service Committee East of England—Essex (REC12/EE/0433).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Patient level data and the full dataset are available from the corresponding author. Participants gave informed consent for data sharing.

References

- 1.Mavaddat N, Peock S, Frost D, Ellis S, Platte R, Fineberg E, Evans DG, Izatt L, Eeles RA, Adlard J, Davidson R, Eccles D, Cole T, Cook J, Brewer C, Tischkowitz M, Douglas F, Hodgson S, Walker L, Porteous ME, Morrison PJ, Side LE, Kennedy MJ, Houghton C, Donaldson A, Rogers MT, Dorkins H, Miedzybrodzka Z, Gregory H, Eason J, Barwell J, McCann E, Murray A, Antoniou AC, Easton DF. Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:812–22. 10.1093/jnci/djt095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs IJ, Menon U, Ryan A, Gentry-Maharaj A, Burnell M, Kalsi JK, Amso NN, Apostolidou S, Benjamin E, Cruickshank D, Crump DN, Davies SK, Dawnay A, Dobbs S, Fletcher G, Ford J, Godfrey K, Gunu R, Habib M, Hallett R, Herod J, Jenkins H, Karpinskyj C, Leeson S, Lewis SJ, Liston WR, Lopes A, Mould T, Murdoch J, Oram D, Rabideau DJ, Reynolds K, Scott I, Seif MW, Sharma A, Singh N, Taylor J, Warburton F, Widschwendter M, Williamson K, Woolas R, Fallowfield L, McGuire AJ, Campbell S, Parmar M, Skates SJ. Ovarian cancer screening and mortality in the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:945–56. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01224-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF, Evans DG, Lynch HT, Isaacs C, Garber JE, Neuhausen SL, Matloff E, Eeles R, Pichert G, Vant'veer L, Tung N, Weitzel JN, Couch FJ, Rubinstein WS, Ganz PA, Daly MB, Olopade OI, Tomlinson G, Schildkraut J, Blum JL, Rebbeck TR. Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. JAMA 2010;304:967–75. 10.1001/jama.2010.1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kauff ND, Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Robson ME, Lee J, Garber JE, Isaacs C, Evans DG, Lynch H, Eeles RA, Neuhausen SL, Daly MB, Matloff E, Blum JL, Sabbatini P, Barakat RR, Hudis C, Norton L, Offit K, Rebbeck TR. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy for the prevention of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast and gynecologic cancer: a multicenter, prospective study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1331–7. 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rebbeck TR, Kauff ND, Domchek SM. Meta-analysis of risk reduction estimates associated with risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:80–7. 10.1093/jnci/djn442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, deFazio A, Emmanuel C, George J, Dobrovic A, Birrer MJ, Webb PM, Stewart C, Friedlander M, Fox S, Bowtell D, Mitchell G. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from The Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2654–63. 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Høberg-Vetti H, Bjorvatn C, Fiane BE, Aas T, Woie K, Espelid H, Rusken T, Eikesdal HP, Listøl W, Haavind MT, Knappskog PM, Haukanes BI, Steen VM, Hoogerbrugge N. BRCA1/2 testing in newly diagnosed breast and ovarian cancer patients without prior genetic counselling: the DNA-BONus study. Eur J Hum Genet Published Online First: 9 Sep 2015. 10.1038/ejhg.2015.196 10.1038/ejhg.2015.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song H, Cicek MS, Dicks E, Harrington P, Ramus SJ, Cunningham JM, Fridley BL, Tyrer JP, Alsop J, Jimenez-Linan M, Gayther SA, Goode EL, Pharoah PD. The contribution of deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2 and the mismatch repair genes to ovarian cancer in the population. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:4703–9. 10.1093/hmg/ddu172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S, Royer R, Li S, McLaughlin JR, Rosen B, Risch HA, Fan I, Bradley L, Shaw PA, Narod SA. Frequencies of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among 1,342 unselected patients with invasive ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2011;121:353–7. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norquist BM, Harrell MI, Brady MF, Walsh T, Lee MK, Gulsuner S, Bernards SS, Casadei S, Yi Q, Burger RA, Chan JK, Davidson SA, Mannel RS, DiSilvestro PA, Lankes HA, Ramirez NC, King MC, Swisher EM, Birrer MJ. Inherited mutations in women with ovarian carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:482–90. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antoniou AC, Cunningham AP, Peto J, Evans DG, Lalloo F, Narod SA, Risch HA, Eyfjord JE, Hopper JL, Southey MC, Olsson H, Johannsson O, Borg A, Pasini B, Radice P, Manoukian S, Eccles DM, Tang N, Olah E, Anton-Culver H, Warner E, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Gorski B, Tryggvadottir L, Syrjakoski K, Kallioniemi OP, Eerola H, Nevanlinna H, Pharoah PD, Easton DF. The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancers: updates and extensions. Br J Cancer 2008;98:1457–66. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans DG, Lalloo F, Wallace A, Rahman N. Update on the Manchester scoring system for BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing. J Med Genet 2005;42:e39 10.1136/jmg.2005.031989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metcalfe KA, Fan I, McLaughlin J, Risch HA, Rosen B, Murphy J, Bradley L, Armel S, Sun P, Narod SA. Uptake of clinical genetic testing for ovarian cancer in Ontario: a population-based study. Gynecol Oncol 2009;112:68–72. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolton KL, Chenevix-Trench G, Goh C, Sadetzki S, Ramus SJ, Karlan BY, Lambrechts D, Despierre E, Barrowdale D, McGuffog L, Healey S, Easton DF, Sinilnikova O, Benítez J, García MJ, Neuhausen S, Gail MH, Hartge P, Peock S, Frost D, Evans DG, Eeles R, Godwin AK, Daly MB, Kwong A, Ma ES, Lázaro C, Blanco I, Montagna M, D'Andrea E, Nicoletto MO, Johnatty SE, Kjær SK, Jensen A, Høgdall E, Goode EL, Fridley BL, Loud JT, Greene MH, Mai PL, Chetrit A, Lubin F, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, Glendon G, Andrulis IL, Toland AE, Senter L, Gore ME, Gourley C, Michie CO, Song H, Tyrer J, Whittemore AS, McGuire V, Sieh W, Kristoffersson U, Olsson H, Borg Å, Levine DA, Steele L, Beattie MS, Chan S, Nussbaum RL, Moysich KB, Gross J, Cass I, Walsh C, Li AJ, Leuchter R, Gordon O, Garcia-Closas M, Gayther SA, Chanock SJ, Antoniou AC, Pharoah PD, EMBRACE; kConFab Investigators; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Association between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and survival in women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. JAMA 2012;307:382–90. 10.1001/jama.2012.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang D, Khan S, Sun Y, Hess K, Shmulevich I, Sood AK, Zhang W. Association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with survival, chemotherapy sensitivity, and gene mutator phenotype in patients with ovarian cancer. JAMA 2011;306:1557–65. 10.1001/jama.2011.1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Candido-dos-Reis FJ, Song H, Goode EL, Cunningham JM, Fridley BL, Larson MC, Alsop K, Dicks E, Harrington P, Ramus SJ, de Fazio A, Mitchell G, Fereday S, Bolton KL, Gourley C, Michie C, Karlan B, Lester J, Walsh C, Cass I, Olsson H, Gore M, Benitez JJ, Garcia MJ, Andrulis I, Mulligan AM, Glendon G, Blanco I, Lazaro C, Whittemore AS, McGuire V, Sieh W, Montagna M, Alducci E, Sadetzki S, Chetrit A, Kwong A, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Høgdall E, Neuhausen S, Nussbaum R, Daly M, Greene MH, Mai PL, Loud JT, Moysich K, Toland AE, Lambrechts D, Ellis S, Frost D, Brenton JD, Tischkowitz M, Easton DF, Antoniou A, Chenevix-Trench G, Gayther SA, Bowtell D, Pharoah PD, for EMBRACE, kConFab I, Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Germline mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 and ten-year survival for women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:652–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, Scott CL, Meier W, Shapira-Frommer R, Safra T, Matei D, Fielding A, Spencer S, Dougherty B, Orr M, Hodgson D, Barrett JC, Matulonis U. Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer: a preplanned retrospective analysis of outcomes by BRCA status in a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:852–61. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70228-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, Scott C, Meier W, Shapira-Frommer R, Safra T, Matei D, Macpherson E, Watkins C, Carmichael J, Matulonis U. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1382–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1105535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horowitz MJ, Hulley S, Alvarez W, Reynolds AM, Benfari R, Blair S, Borhani N, Simon N. Life events, risk factors, and coronary disease. Psychosomatics 1979;20:586–92. 10.1016/S0033-3182(79)70763-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferla R, Calò V, Cascio S, Rinaldi G, Badalamenti G, Carreca I, Surmacz E, Colucci G, Bazan V, Russo A. Founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Ann Oncol 2007;18(Suppl 6):vi93–8. 10.1093/annonc/mdm234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlich-Bakker KJ, Ausems MG, Schipper M, Ten Kroode HF, Wárlám-Rodenhuis CC, van den Bout J. BRCA1/2 mutation testing in breast cancer patients: a prospective study of the long-term psychological impact of approach during adjuvant radiotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;109:507–14. 10.1007/s10549-007-9680-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulbert-Williams NJ, Storey L. Psychological flexibility correlates with patient-reported outcomes independent of clinical or sociodemographic characteristics. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:2513–21. 10.1007/s00520-015-3050-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craufurd D, Tyler A. Predictive testing for Huntington's disease: protocol of the UK Huntington's Prediction Consortium. J Med Genet 1992;29:915–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George A. UK BRCA mutation testing in patients with ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 2015;113(Suppl 1):S17–21. 10.1038/bjc.2015.396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eccles BK, Copson E, Maishman T, Abraham JE, Eccles DM. Understanding of BRCA VUS genetic results by breast cancer specialists. BMC Cancer 2015;15:936 10.1186/s12885-015-1934-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sie AS, van Zelst-Stams WA, Spruijt L, Mensenkamp AR, Ligtenberg MJ, Brunner HG, Prins JB, Hoogerbrugge N. More breast cancer patients prefer BRCA-mutation testing without prior face-to-face genetic counseling. Fam Cancer 2014;13:143–51. 10.1007/s10689-013-9686-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jmedgenet-2016-103902supp.pdf (242.2KB, pdf)