Graphical abstract

Keywords: Ag NPs, Antibacterial agent, Green synthesis, Parkia speciosa Hassk, Microwave, Nanoparticles

Abstract

This paper reports an investigation of the microwave-assisted synthesis of silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) using extract of stinky bean (Parkia speciosa Hassk) pods (BP). The formation of Ag NPs was identified by instrumental analysis consists of UV–vis spectrophotometry, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrophotometry, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and particle size analysis. Furthermore, Ag NPs were used as antibacterial agents against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The results indicate rapid formation of Ag NPs during microwave irradiation with similar properties to those obtained through the aging method. In general, the use of microwave irradiation yields larger particles, and it is affected by volume ratio of the extract to the AgNO3 solution. The prepared materials demonstrated antibacterial activity.

Introduction

Nanotechnology has become a popular and necessary technology in recent years. Nanotechnology itself addresses nanoparticles that are atomic or molecular aggregates characterized by size of less than 100 nm. The application of nanotechnology in medical applications, commonly referred to as “nanomedicine”, seeks to deliver a new set of tools, devices and therapies for the treatment of human disease. Nanomaterials that can act as biological mimetics, “nanomachines”, biomaterials for tissue engineering, shape-memory polymers as molecular switches, biosensors, laboratory diagnostics and nanoscale devices for drug release, are just a few of the applications being explored [1]. Some nanoparticles have been reported as having therapeutic potential. For example, in cancer detection, silver and gold nanoparticles were utilized. In other cases, nanoparticles such as silver, gold, and ZnO were used as antibacterial agents and some therapeutic uses [2], [3], [4], in conjunction with some routes and simple technique for developing nanoparticle synthesis. Of the nanoparticles used in the pharmaceutical industry, silver nanoparticles are one of the important materials in nanomedicine. Silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) have been used as antibacterial agents for topical application for bacterial skin infections [5], [6]. In other cases, Ag NPs have received much attention for their potential use in cancer therapy from many reports showing that Ag NPs effectively induce selective killing of cancer cells as well as play a role in drug delivery. The synthesis of Ag NPs can be conducted by many routes, and the most used route is the chemical reduction of Ag+ ions from aqueous solution. The most popular reducing agent for mild condition is sodium borohydride (NaBH4). Many investigations suggest several synthesis routes using plant extracts as reducing agents instead of NaBH4 in a green synthesis or biosynthesis scheme for Ag NPs. Use of extract of Neem (Azadirachta indica L), Acalypha indica, Azadirachta, Emblica and Cinnamomum Emblica officianalis, lemongrass and other potential plants has been reported [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. The specific compounds that act as reducing agents and support the antimicrobial activity of Ag NPs are generally flavonoids and polyphenol compounds. Another method of green synthesis is the use of more effective, energy efficient and rapid methods of preparation. Microwave irradiation (MW), sonochemistry and other rapid techniques have been used [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. In previous reports, MW has been utilized for synthesis of Ag NPs, ZnO NPs, magnetite, TiO2 and other nanoparticles with some advantages, the most important being the rapid and efficient nature of the procedure [10], [14], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]. With different rates of nanoparticles formation, the use of MW also can be used to generate different morphologies [27]. For example, MW-assisted synthesis of ZnO gives a flower-like morphology that is influenced by the radiation power [28].

Here, we investigated the use of the stinky bean or Parkia speciosa Hassk. a plant indigenous to Southeast Asia including Indonesia [29]. It is reported that the stinky bean and its pods contain antioxidant, vitamin, oil and poly phenolic compounds. Traditionally, the stinky bean and its hull are used as an itch remedy. From previous research, the chemical composition of stinky bean pods includes active organic compounds such as flavonoids, saponins, and tannins. The phenolic content of BP extract was reported to be approximately 50–85 wt.%, and the flavonoid content is approximately 5–6 wt.% [30], [31], [32]. Due to the possible potency of BP, this study aimed to investigate the utilization of SB extract as reducing agent in Ag NPs synthesis. In addition, the effect of the use of MW and the concentration of BP extract on Ag NP characteristics was studied. Through the comparison with the formation without MW (aging method), the rate and profile of NPs are intensively discussed in light of their antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Considering green chemistry principles, simple extraction of the raw material was conducted by using water as solvent. The effect of parameter synthesis, the volume ratio of the SB extract to AgNO3 solution to the NPs formation, was also investigated.

Material and method

Materials

SBP extract was obtained from stinky beans cultivated in Sleman district, Yogyakarta Province, Indonesia. Identification of the stinky bean was performed by the Laboratory of Plant Taxonomy, Faculty of Biology, Gadjah Mada University. The empty BP samples were air dried before extraction. Ten grams of BP was refluxed in 100 mL water for 2 h to obtain the BP extract. Silver nitrate (AgNO3) (ACS reagent, ⩾99.0%) and Chloramphenicol (ACS reagent, ⩾99.0%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA), and E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa were supplied by ATCC Company (Manassas, VA, USA) and stored at the Microbiology Laboratory, Department of Pharmacy, Universitas Islam Indonesia. Deionized water (produced by Integrated Laboratory, Universitas Islam Indonesia) was used throughout.

Synthesis of silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs)

Aqueous solution (10−3 M) of silver nitrate (AgNO3) was prepared in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, and BP extract was added for reduction into Ag+ ions. The mixture was then heated in a microwave oven for complete bioreduction at a power of 300 W for 4 min. A commercial MW oven with a 2.45 GHz frequency was used. The color change of the SBP extract from light yellowish to reddish brown was recorded by UV–vis spectrophotometric analysis. As a comparison, the same mixture was prepared and aged for 24 h before being monitored using UV–vis spectrophotometry. For XRD and SEM analysis, the solution was filtered to yield fine particles to be thin filmed on the glass surface. The Ag NPs obtained from the microwave irradiation and aging methods are designated as Ag NPs-mw and Ag NPs-aging, respectively. In order to evaluate the effect of the volume ratio of the silver nitrate solution with respect to the BP extract on the particle size distribution and its antibacterial activity, the volume ratio in AgNPs-mw preparation was varied at 10:1, 20:1 and 40:1.

Nanoparticle characterization

UV-absorption spectra of synthesized Ag NPs were characterized using a HITACHU U-2010 UV–vis spectrometer, HITACHI (Tokyo, Japan). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was conducted using Philip XL 30, SEMTech (Tokyo, Japan) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed using JEOL-JEM 1400 (Freising, Germany). The particle size distributions of the synthesized Ag NPs were determined by the particle size analyzer HORIBA-X, HORIBA Scientific (Kyoto, Japan). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectral measurements using FTIR-UATR Spectrum Two, Perkin Elmer (Massachusetts, USA) were carried out to identify the functional groups contained in the BP extract. The XRD pattern of Ag NPs was obtained with a Shimadzu X-6000 (Kyoto, Japan) instrument and the Rietveld refinement was conducted by using Rietica. The solvent of the Ag NPs liquid sample was evaporated, and the powder was dispersed onto a glass film before analysis.

Antibacterial activity of Ag NPs

The antibacterial activity of the extract and Ag NPs was measured for E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa by the disk diffusion method. The disks were soaked with double distilled water, BP extract and the Ag NP solution separately. Varied concentrations of the Ag NPs were used to ensure identification of the antibacterial activity. The disks were air dried in sterile conditions before being placed in agar media containing the microbial cultures. Plates containing media as well as cultures were divided into four equal parts and previously prepared disks were placed on each part of the plate. The disk soaked with double distilled water was utilized as the negative control, and disk soaked with chloramphenicol (30 μg/mL) was used as the positive control. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h. The maximum zone of inhibition was observed and measured for analysis against each type of test microorganism.

Results and discussion

Ag NPs characterization

The UV–vis spectra of BP extract and the Ag NPs are displayed in Fig. 1. The extract color change from yellowish to reddish brown was exhibited by Ag reduction, also from the UV–vis spectra there are blue shifts of the spectra after the reduction. The absorption spectra of the extract are in the range of 271–273 nm while Ag NPs formed by both method have a peak wavelength of 445 nm. These changes are due to the rapid change of the surface plasmon resonance of Ag NPs. This change is denoted by the broadening of the peak, which indicates the formation of polydispersed large nanoparticles due to slow reduction rates. Ag NPs-mw exhibits the higher absorbance than Ag NP-aging in the maximum wavelength implied that more rapid bioreduction was achieved. Visually the final color of Ag NPs-mw is darker compared to Ag NPs-aging.

Fig. 1.

UV–vis spectra of BP extract and the Ag NPs.

SEM profiles of the drop coated films of Ag NPs with varied magnifications are depicted in Fig. 2. The images present the aggregate formation of Ag NPs with spherical-like formation by both methods. EDS analysis confirms that the aggregates are silver nanocrystals in that typical optical absorption peak is shown at approximately 3 keV. The aggregate formation in SEM analysis is related to the sample preparation procedure to the sample in that the nanoparticles need to be filtered and dried before measurement. Different surface morphology of the particles is found from varied methods in which the flake type is obtained from microwave assisted Ag NPs while the aging method presents spherical-like aggregates. The EDX analysis of the silver nanoparticles revealed only Ag content indicating no silver oxide formation. TEM profiles in Fig. 3 also show that the formed Ag NPs are in the range of nanoparticle size at around 20–50 nm. The TEM images exhibits the mixture of shapes with mainly spherical shapes are predominant. Also from the images, thin layer of organic material from plant is observed as well as reported by some previous reports utilizing plant extracts [33], [34].

Fig. 2.

SEM-EDX profile (a) Ag NPs-aging and (b) Ag NPs-mw.

Fig. 3.

TEM profile of (a) Ag NPs-aging and (b) Ag NPs-mw.

Comparison on the FTIR spectra of the BP extract and Ag NPs is displayed in Fig. 4. The FT-IR spectra of BP extract show several major peaks at 3292, 2917, 2849, 2112, 1742, 1630, 1420, 1375, 1147 and 1043 cm−1 and some other peaks approximately at 1000 cm−1. The peak at 3292 cm−1 represents the —OH stretching vibration from phenolic compounds in the extract while the three peaks at 2849, 1375 and 1043 cm−1 are probably attributable to the NH stretching vibration of amide II, C—O stretch and C—N stretching of amines, respectively. The peak at 1630 cm−1 is designated as the stretching vibration of C O bond. After the Ag NPs formation, there are some shifts of valuable peaks such as the O-H vibration from 3292 to 3306 cm−1, C O vibration from 1630 to 1634 cm−1, and N—H vibration from 1043 to 1045 cm−1, indicating that reduction occurred. Overall, the spectra of Ag NPs-mw and Ag NPs-aging are similar.

Fig. 4.

FTIR spectra of (a) BP extract, (b) Ag NPs-aging and (c) Ag NPs-mw.

The presence of silver is also confirmed by the XRD patterns in Fig. 5. The characteristics of diffraction peaks at 38.28°, 44.33°, 64.33°, and 77.53° correspond to the (1 1 1), (2 0 0), (2 2 0) and (3 1 1) planes, respectively. The peaks are in good agreement with face centered cubic (FCC) silver with a lattice parameter of a = 4.08 Å, which is also in agreement with the joint committee of powder diffraction standard (JCPDS) Card No-087-0720 data [16]. From the Rietveld refinement, the patterns also confirm that no oxide Ag species formed. From the calculation using the Scherrer’s formula for the crystallite domain size:

| (1) |

Fig. 5.

XRD pattern of AgNPs-aging (above) and Ag NPs-mw (below).

The crystallite size is calculated to be approximately 18 nm and 17 nm. The Ag NPs-mw are slightly bigger than Ag NPs-aging.

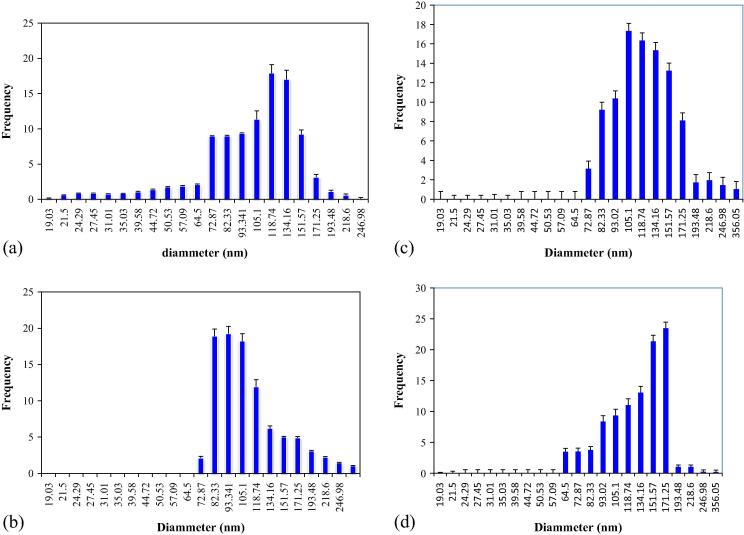

Fig. 6 presents the particle size distributions of Ag NPs prepared by different methods and the volume ratio of silver solution to SBP extract. With the same volume ratio, the results showed that the particle size distribution of Ag NPs-mw has a larger size (114.41 nm) than Ag NPs-aging (104.38 nm). The distribution suggests the formation of particle aggregates with increasing energy transfer during the rapid reduction reaction caused by microwave irradiation. The variation of the volume ratio indicates that the higher the concentration of SBP extract, the smaller particle size diameter distribution of the Ag NPs will be. The particle size distribution means are 114.41 nm, 127.60 nm and 160.67 nm for the ratio of 10:1; 20:1 and 40:1, respectively. The data suggest that the reduction mechanism is controlled by the amount of reducing agent.

Fig. 6.

Particle size distribution of (a) Ag NPs-aging and (b–d) Ag NPs-mw with the volume ratio of 10:1, 20:1 and 40:1 respectively.

Ag NPs antibacterial activity

Although the mechanism for the antimicrobial action of silver ions is not clearly understood, quantum size effect of silver ions on microbe is reported from several investigations. The effect of Ag NPs synthesis parameters on the antimicrobial activity compared with SBP extract, double distilled water as negative control and chloramphenicol as positive control is expressed by the data in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of antibacterial activity test of SBP extract and AgNPs.

| Antibacterial agent | Inhibition zone (mm) after incubation for 24 h |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | |

| SBP extract | 7.3 | 7.6 | 7.6 |

| AgNPs-aging | 6.9 | 7.6 | 8.6 |

| AgNPs-mw | |||

| 10:1 | 8.6 | 10.4 | 11.8 |

| 20:1 | 6.8 | 8.2 | 9.8 |

| 40:1 | 6.8 | 8.2 | 8.3 |

| Chloramphenicol (positive control) | 23.6 | 23.8 | 7.6 |

| Double distilled water (Negative control) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Ag NPs demonstrate higher antibacterial activity than the SBP extract for all tested microbes. Ag NPs exhibit high activity against P. aeruginosa as shown by the wider inhibition zone compared to chloramphenicol as the positive control while for the other microbes the activity of Ag NPs is between the SBP extract and chloramphenicol. The results of the varied volume ratio show that the higher ratio exhibits the lowest antibacterial activity. This phenomenon is in line with the particle size distribution resulting from the variable ratio. It has been reported that the smaller particle size contributes to more effective interaction and interference with microbial DNA [14].

Conclusions

Synthesis of stinky bean pod extract reduced Ag NPs with the microwave irradiation method and the effect of extract concentrations were studied. Microwave irradiation provides rapid formation of Ag NPs with larger particle size compared to aging method. The concentration of the extract affects the particle size distribution, as well as antibacterial activity against S. aureus, E. coli and P. aeruginosa.

Conflict of Interest

The author has declared no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges with thanks the Department of Chemistry, Universitas Islam Indonesia for providing the financial assistance in the research activity, Dara Safrina for bean photograph and the Nanopharmacy Research Center, Universitas Islam Indonesia for use of the particle size analysis instrument.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Hartemann P., Hoet P., Proykova A., Fernandes T., Baun A., De Jong W., et al. Nanosilver: safety, health and environmental effects and role in antimicrobial resistance. Mater Today. 2015;18:122–123. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pati R., Mehta R., Mohanty S., Padhi M., Sengupta M., Vaseeharan B., et al. Topical application of zinc oxide nanoparticles reduces bacterial skin infection in mice and exhibits antibacterial activity by inducing oxidative stress response and cell membrane disintegration in macrophages. Nanomedicine. 2014;10:1195–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bankar A., Joshi B., Kumar A.R., Zinjarde S. Banana peel extract mediated novel route for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Colloid Surf A. 2010;368:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siva Vijayakumar T., Karthikeyeni S., Vasanth S., Ganesh A., Bupesh G., Ramesh R., et al. Synthesis of silver-doped zinc oxide nanocomposite by pulse mode ultrasonication and its characterization studies. J Nanosci. 2013;2013:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma L., Jia I., Guo X., Xiang L. Catalytic activity of Ag/SBA-15 for low temperature gas phase selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde. Chinese J Catal. 2014;35:108–119. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gopinath P.M., Narchonai G., Dhanasekaran D., Ranjani A., Thajuddin N. Mycosynthesis, characterization and antibacterial properties of AgNPs against multidrug resistant (MDR) bacterial pathogens of female infertility cases. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2015;10:138–145. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalil M.M.H., Ismail E.H., El-Baghdady K.Z., Mohamed D. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using olive leaf extract and its antibacterial activity. Arabian J Chem. 2014;7:1131–1139. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhand V., Soumya L., Bharadwaj S., Chakra S., Bhatt D., Sreedhar B. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Coffea arabica seed extract and its antibacterial activity. Mater Sci Eng C. 2016;58:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honary S., Barabadi H., Gharaei-Fathabad E., Naghibi F. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles induced by the fungus penicillium citrinum. Tropical J Pharm Res. 2013;12:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasireddy R., Paul R., Krishna A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and the study of optical properties. Nanomate Nanotechnol. 2012;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma G., Sharma A.R., Kurian M., Bhavesh R., Nam J.S., Lee S.S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticle using Myristica fragrans (nutmeg) seed extract and its biological activity. Digest J Nanomater Biostruct. 2014;9:325–332. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muniyappan N., Nagarajan N.S. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Curcuma pseudomontana essential oil, its biological activity and cytotoxicity against human ductal breast carcinoma cells T47D. J Environ Chem Eng. 2014;2:2037–2044. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umoren S.A., Obot I.B., Gasem Z.M. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using red apple (Malus domestica) fruit extract at room temperature. J Mater Environ Sci. 2014;5:907–914. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velusamy P., Das J., Pachaiappan R. Greener approach for synthesis of antibacterial silver nanoparticles using aqueous solution of neem gum (Azadirachta indica L.) Ind Crops Products. 2015;66:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moosa A.A., Ridha A.M., Al-kaser M. Process parameters for green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves extract of aloe vera plant. Int J Mutidiciplinary Current Res. 2015;3:966–975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph S., Mathew B. Microwave-assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and the study on catalytic activity in the degradation of dyes. J Mol Liq. 2015;204:184–191. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma Y., Pang Y., Liu F., Xu H., Shen X. Biomolecular spectroscopy microwave-assisted ultrafast synthesis of silver nanoparticles for detection of Hg 2 + Spectrochimica Acta A. 2016;153:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raghavendra G.M., Jung J., Seo J. Microwave assisted antibacterial chitosan – silver nanocomposite films. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;84:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nazeruddin G.M., Prasad N.R., Prasad S.R., Shaikh Y.I., Waghmare S.R., Adhyapak P. Coriandrum sativum seed extract assisted in situ green synthesis of silver nanoparticle and its anti-microbial activity. Ind Crops Prod. 2014;60:212–216. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dar N., Chen K.-Y., Nien Y.-T., Perkas N., Gedanken A., Chen I.-G. Sonochemically synthesized Ag nanoparticles as a SERS active substrate and effect of surfactant. Appl Surf Sci. 2015;331:219–224. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutta D.P., Tyagi A.K. Facile sonochemical synthesis of Ag modified Bi4Ti3O12 nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light. Mater Res Bull. 2016;74:397–407. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pati S.S., Kalyani S., Mahendran V., Philip J. Microwave assisted synthesis of magnetite nanoparticles. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2014;14:5790–5797. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.8842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vankar P.S., Shukla D. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using lemon leaves extract and its application for antimicrobial finish on fabric. Appl Nanosci. 2012;2:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vijayashree I.S., Yallappa S., Niranjana P., Manjanna J. Microwave assisted synthesis of stable biofunctionalized silver nanoparticles using apple fruit (Malus domestica) extract. Adv Mater Lett. 2014;4:598–603. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang B., Zhuang X., Deng W., Cheng B. Microwave-assisted synthesis of silver nanoparticles in alkalic carboxymethyl chitosan solution. Engineering. 2010;2:387–390. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X., Tian J., Fei C., Lv L., Wang Y., Cao G. Rapid construction of TiO2 aggregates using microwave assisted synthesis and its application for dye-sensitized solar cells. RSC Adv. 2015;5:8622–8629. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin H., Yamamoto T., Wada Y., Yanagida S. Large-scale and size-controlled synthesis of silver nanoparticles under microwave irradiation. Mater Chem Phys. 2004;83:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasanpoor M., Aliofkhazraei M., Delavari H. Microwave-assisted synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Proc Mater Sci. 2015;11:320–325. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasima, Faridah D.N., Kurniawati D.A. Antibacterial activity of Parkia speciosa Hassk peel to Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus bacteria. J Chem Pharm Res. 2015;7:239–243. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aisha A., Abu-Salah’ K.M., Alrokayan S.A., Majid A.M.S.A. Evaluation of antiangiogenic and antoxidant properties of Parkia speciosa Hassk extracts. Pakistan J Pharm Sci. 2012;4:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wonghirundecha S., Soottawat B., Sumpavapol P. Total phenolic content, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of stink bean (Parkia speciosa Hassk) pod extracts. Songkl J Sci Technol. 2014;36:301–308. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aden AZ, Mawardika H, Vilansari N, Agustin F, Silvana GT. Uji Efektivitas Ekstrak Kulit Petai(Parkia speciosa Hassk) pada Mencit Balb sebagai Obat Anti-imflamasi Rheumatoid Arthitis; Universitas Brawijayamalang, Malang, 2013.

- 33.Roy S., Das T.K. Plant mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles – a review. Int J Plant Biol Res. 2015;3 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed S., Ahmad M., Swami B.L., Ikram S. A review on plants extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications: a green expertise. J Adv Res. 2016;7:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]