Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated predictors of unresponsiveness to second-line intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment for Kawasaki disease (KD).

Methods

This was a single-center analysis of the medical records of 588 patients with KD who had been admitted to Asan Medical Center between 2006 and 2014. Related clinical and laboratory data were analyzed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Results

Eighty (13.6%) of the 588 patients with KD were unresponsive to the initial IVIG treatment and received a second dose. For these 80 patients, univariate analysis of the laboratory results obtained before administering the second-line IVIG treatment showed that white blood cell count, neutrophil percent, hemoglobin level, platelet count, serum protein level, albumin level, potassium level, and C-reactive protein level were significant predictors. The addition of methyl prednisolone to the second-line regimen was not associated with treatment response (odds ratio [OR], 0.871; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.216–3.512; P=0.846). Multivariate analysis revealed serum protein level to be the only predictor of unresponsiveness to the second-line treatment (OR, 0.160; 95% CI, 0.028–0.911; P=0.039). Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis to determine predictors of unresponsiveness to the second dose of IVIG showed a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 72% at a serum protein cutoff level of <7.15 g/dL.

Conclusion

The serum protein level of the patient prior to the second dose of IVIG is a significant predictor of unresponsiveness. The addition of methyl prednisolone to the second-line regimen produces no treatment benefit.

Keywords: Kawasaki disease, Mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, Immunoglobulins, Serum proteins

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute, self-limiting vasculitis that occurs predominantly in young children1) and is now acknowledged as a common acquired heart disease in this population. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is the most effective first-line treatment during the acute phase of illness. However, approximately ≥10% of patients with KD fail to defervesce following an initial IVIG treatment1). The rate of unresponsiveness to initial IVIG is reported to be as high as 38.3%2). Unresponsiveness 2,3,4,5,6) and prolonged fever7,8,9) have also been reported to be significant risk factors for coronary artery lesions. Despite the significant level of unresponsiveness to first-line treatment in patients with KD, the best second-line treatment remains unknown. The administration of a second IVIG dose is currently the most common therapeutic strategy in unresponsive cases10,11). Although the rate of unresponsiveness to second-line treatment with IVIG has been reported as 22%–49% 12,13,14,15,16,17), no studies have reported on the prediction of unresponsiveness to second-line IVIG treatment.

The purpose of our current study was to investigate the predictor of the unresponsiveness to the additional administration of IVIG as the second-line treatment. We conducted a retrospective, single center study to find out a clinical/laboratory variable associated with the unresponsiveness to the second IVIG treatment.

Materials and methods

1. Subjects

From January 2006 to December 2014, 797 patients with KD were admitted and managed at Asan Medical Center. The diagnostic criteria for KD followed American Heart Association guidelines1). Among 588 patients with complete presentation of principal clinical features who were treated with initial IVIG (2 g/kg), 80 patients with demonstrated unresponsiveness were enrolled as our current study subjects. Patients demonstrating incomplete presentation of principal clinical features, displaying spontaneous recovery before the administration of initial IVIG, admitted after the 10th day of illness, or transferred from other institutes without complete initial clinical/laboratory data were excluded.

Before 2009, the second-line treatment regimen consisted of additional administration of IVIG, but after 2009 consisted of combination IVIG and IV methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg/day for 2 or 3 days). We defined unresponsiveness to treatment as persistent or recrudescent fever 36 hours after completion of initial IVIG administration.

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (2015-0368), and the requirement for informed patient consent was waived.

2. Data collection

Clinical and laboratory data were collected through medical record review. The subjects were divided into 2 groups according to second-line IVIG treatment response. Group 1 consisted of children that were responsive to second-line IVIG treatment and group 2 consisted of children that were unresponsive to second-line IVIG treatment.

Clinical data such as age, height, body weight, clinical features and duration of fever before initial IVIG treatment, were collected at the time of first-line IVIG treatment. Laboratory data were collected retrospectively (1) before initial IVIG treatment and (2) before second-line treatment. If a laboratory test was performed ≥2 times during each period, the highest value was selected for the following tests: white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophil percent, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum aspartate aminotransferase level, alanine transaminase level, total bilirubin level, C-reactive protein level, lactate dehydrogenase level, and brain natriuretic peptide level. For hemoglobin concentration, platelet counts, serum protein level, albumin level, and electrolyte concentration, the lowest value was selected. A fractional change (FC) in the laboratory data was obtained through an additional calculation; FC (%)=(value before initial treatment–the value before second line treatment)/(the value before second line treatment)18).

We measured coronary artery diameter at each phase of illness within three months of fever onset. The highest value among the measurements was selected and used to calculate the z score using the formula by Dallaire and Dahdah19). Coronary artery dilatation was defined as a z score ≥2.5. Giant aneurysms were defined by a diameter >8 mm or a z score ≥10.

3. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). All continuous variables are described as a mean±standard deviation. All categorical variables are described as a frequency with percentage. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to determine predictors of unresponsiveness to second-line IVIG treatment. Additionally, receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis for the predictor was performed. The z score of coronary artery diameters was compared between the 2 groups using a t test. Statistical significance was defined as a P<0.05.

Results

The clinical characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1. None of the clinical variables were significant predictors of unresponsiveness to second-line IVIG treatment.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the study subjects.

| Characteristic | Group 1 (n=71) | Group 2 (n=9) |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 23 (32.4) | 2 (22.2) |

| Age (mo) | 29.5±22.0 | 36.2±24.2 |

| Body weight (kg) | 13.2±4.7 | 14.4±5.5 |

| Height (cm) | 89.2±16.1 | 93.1±18.7 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 0.56±0.15 | 0.60±0.18 |

| Principal clinical features | ||

| Conjunctival injection | 69 (97) | 8 (89) |

| Changes in lips/oral cavity | 68 (96) | 9 (100) |

| Changes in extremities | 67 (94) | 8 (89) |

| Polymorphous exanthema | 68 (96) | 9 (100) |

| Cervical lymphadenopathy | 47 (66) | 6 (67) |

| Duration of fever before initial IVIG (day) | 5.9±1.7 | 5.0±0.5 |

| No. of methylprednisolone combination | 34 (48) | 4 (44) |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Group 1, responsive to second-line IVIG treatment; group 2, unresponsive to second-line IVIG treatment; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin.

The laboratory data for the subjects are presented in Table 2. WBC count, neutrophil percent, hemoglobin level, platelet count, and serum protein level, albumin level, potassium level, and C-reactive protein level were significant predictors by univariate analysis when evaluated before second-line IVIG treatment. Among the laboratory data obtained before initial IVIG treatment, only the serum chloride level was significant. Univariate analysis was also performed on the FC of laboratory variables. The FC of serum protein level (odds ratio [OR], 0.0, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.0–0.064, P=0.016) and C-reactive protein level (OR, 23.986; 95% CI, 2.915–194.407; P=0.003) were significant in univariate analysis. The FC of serum protein level was 0.15%±0.14% in group 1 and –0.01%±0.12% in group 2. The value of FC for C-reactive protein level was -0.38%±0.36% in group 1 and 0.36%±0.66% in group 2. Methyl prednisolone was used as an additional drug to second-line IVIG treatment in 34 subjects (48%) from group 1 and 4 subjects (44%) from group 2. Methyl prednisolone use was not a significant predictor for unresponsiveness to second-line IVIG treatment (OR, 0.871; 95% CI, 0.216–3.512; P=0.846).

Table 2. Laboratory data of the study subjects.

| Variable | Initial evaluation | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | Before 2nd IVIG | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n=71) | Group 2 (n=9) | Group 1 (n=71) | Group 2 (n=9) | |||||||

| WBC count (/mm3) | 14,383±5,529 | 14,642±2,613 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.902 | 12,739±4,740 | 19,088±7,563 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.005* |

| Neutrophil (%) | 72.33±13.10 | 80.64±7.32 | 1.070 | 0.984–1.163 | 0.114 | 54.66±15.69 | 74.48±12.28 | 1.119 | 1.041–1.203 | 0.002* |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.4±1.0 | 10.8±1.3 | 0.575 | 0.276–1.199 | 0.140 | 10.6±1.1 | 9.5±1.4 | 0.458 | 0.242–0.868 | 0.017* |

| Platelet (×103/mm3) | 303±88 | 292±59 | 0.999 | 0.989–1.008 | 0.756 | 387±136 | 286±116 | 0.992 | 0.984–0.999 | 0.036* |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 72.4±29.5 | 75±30 | 1.003 | 0.976–1.031 | 0.823 | 87±25 | 78±33 | 0.987 | 0.958–1.018 | 0.404 |

| Protein (g/dL) | 6.5±0.8 | 6.3±0.6 | 0.763 | 0.292–1.993 | 0.581 | 7.4±0.7 | 6.1±0.7 | 0.089 | 0.022–0.355 | 0.001* |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.4 ±0.5 | 3.2±0.5 | 0.470 | 0.098–2.240 | 0.343 | 2.7±0.5 | 2.2±0.3 | 0.035 | 0.003–0.459 | 0.011* |

| AST (IU/L) | 128±141 | 72±34 | 0.995 | 0.984–1.005 | 0.325 | 44±35 | 30±11 | 0.958 | 0.888–1.034 | 0.274 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 161±180 | 125±97 | 0.999 | 0.993–1.004 | 0.604 | 58 ±54 | 33±14 | 0.983 | 0.957–1.010 | 0.223 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.5 ±1.3 | 2.2±1.6 | 1.388 | 0.833–2.313 | 0.208 | 0.5±0.6 | 1.3 ±1.6 | 1.979 | 1.001–3.912 | 0.050 |

| Na+ (mEq/L) | 135±4.0 | 132±2 | 0.782 | 0.600–1.020 | 0.070 | 135±2 | 135±1 | 0.961 | 0.683–1.351 | 0.818 |

| K+ (mEq/L) | 4.2±0.5 | 3.9±0.3 | 0.318 | 0.067–1.505 | 0.149 | 4.5±0.5 | 4.0±0.8 | 0.219 | 0.055–0.873 | 0.031* |

| Cl− (mEq/L) | 101±4 | 98±1 | 0.790 | 0.626–0.996 | 0.046* | 101±3 | 101±5 | 0.999 | 0.770–1.296 | 0.994 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 12.19±8.26 | 14.56±5.30 | 1.034 | 0.946–1.130 | 0.458 | 7.31±6.33 | 19.89±7.35 | 1.209 | 1.090–1.342 | <0.001* |

| LDH (IU/L) | 255±88 | 206±25 | 0.988 | 0.961–1.017 | 0.425 | 252±42 | 218±75 | 0.986 | 0.951–1.023 | 0.450 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 144±244 | 265±226 | 1.001 | 0.999–1.004 | 0.311 | 219±467 | 627±387 | 1.001 | 1.000–1.003 | 0.160 |

| Urine WBC ≥10/HPF | 31 (44) | 6 (67) | 6.581 | 0.750–57.764 | 0.089 | 2 (3) | 1 (11) | 4.000 | 0.341–51.027 | 0.286 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

Group 1, responsive to second-line IVIG treatment; group 2, unresponsive to second-line IVIG treatment; CI, confidence interval; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; WBC, white blood cell count; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CRP, C-reactive protein; LDH, lactic acid dehydrogenase; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; HPF, high power field.

*P<0.05, indicating significance as a predictor for unresponsiveness to second-line intravenous immunoglobulin treatment.

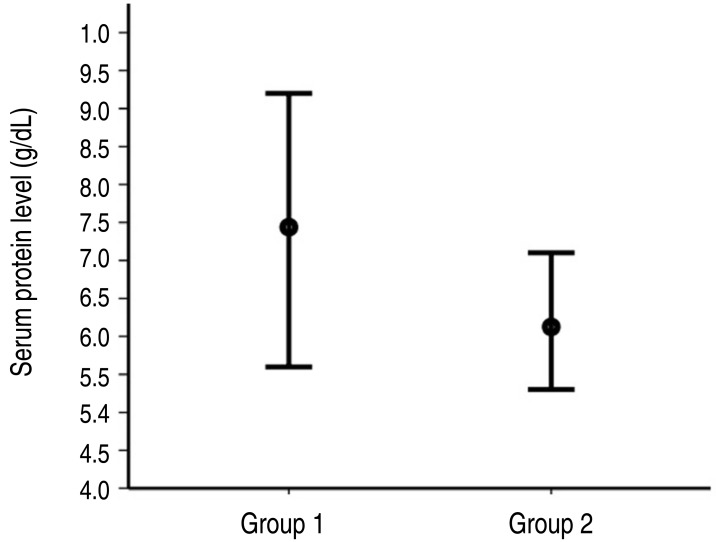

A multivariate logistic regression analysis conducted for the model consisted of 4 variables with relatively lower P values (WBC count, neutrophil percentage, serum protein level, and serum C-reactive protein level) before second-line treatment (Table 3). Serum protein level was only predictor for unresponsiveness to second-line IVIG treatment (OR, 0.160; 95% CI, 0.028–0.911; P=0.039) (Fig. 1).

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine predictors of unresponsiveness to second-line intravenous immunoglobulin treatment.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC count (/mm3) | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.803 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 1.032 | 0.928–1.147 | 0.565 |

| Protein (g/dL) | 0.160 | 0.028–0.911 | 0.039* |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 1.116 | 0.977–1.275 | 0.107 |

CI, confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell count; CRP, C-reactive protein.

*P<0.05, indicating significance as a predictor for unresponsiveness to second-line intravenous immunoglobulin treatment.

Fig. 1. The serum protein level ranges before administration of the second-line intravenous iimmunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment in each group. The circle on the bar indicates the mean. Group 1, responsive to second-line IVIG treatment; group 2, unresponsive to second-line IVIG treatment.

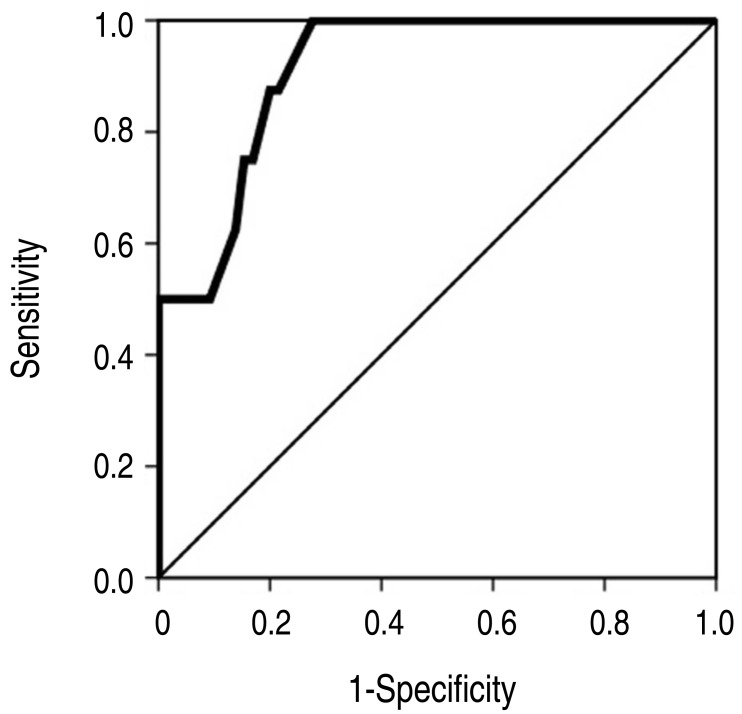

The result of ROC analysis is presented in Fig. 2. Area under curve was 0.913(95% CI, 0.835–0.992). In the prediction of the unresponsiveness to second-line IVIG treatment, the sensitivity was 88% and the specificity was 80% at the cutoff level of <6.95 g/dL. The sensitivity was 100% and the specificity was 72% at the cutoff level of <7.15 g/dL because the highest value of serum protein level was 7.1 g/dL in subjects of group 2 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of the serum protein levels before administration of the second-line intravenous immunoglobulin treatment to determine predictors of unresponsiveness.

The coronary artery diameter was significantly larger in group 2 compared with group 1 (Table 4). Fourteen subjects (20%) in group 1 and 4 subjects (44%) in group 2 had a coronary artery dilatation. Two subjects in group 2 had a giant aneurysm.

Table 4. Comparison of coronary artery diameters between groups.

| Variable | Group 1 (n=71) | Group 2 (n=9) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left main CA (mm) | 2.43±0.45 | 2.86±0.80 | 0.020 |

| Z score | 1.25±1.19 | 2.21±2.28 | 0.047 |

| Left anterior descending CA (mm) | 2.08±0.78 | 3.19±1.63 | 0.001 |

| Z score | 0.26±1.75 | 3.09±4.19 | <0.001 |

| Right CA (mm) | 2.02±0.62 | 2.76±1.82 | 0.013 |

| Z score | 0.11±1.53 | 1.99±5.06 | 0.017 |

| No. of coronary artery dilatation | 14 (20) | 4 (44) | 0.023 |

| No. of giant aneurysm | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | - |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

Group 1, responsive to second-line intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment; group 2, unresponsive to second-line IVIG treatment; CA, coronary artery.

Discussion

To find out the predictor for second-line IVIG treatment, we additionally investigated laboratory data collected before second-line treatment after initial IVIG treatment, as well as laboratory data before the initial IVIG treatment which have been analyzed for the prediction of unresponsiveness to initial IVIG treatment by other authors18,20,21,22). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that serum protein levels collected before second-line IVIG treatment was a significant predictor of unresponsiveness. This result has clinical significance, as it might help physicians make appropriate therapeutic decisions and enable counseling of KD patients who are unresponsive to the initial IVIG treatment.

Currently, the most frequently selected second-line treatment in patients with KD refractory to initial treatment is exclusive administration of IVIG. IVIG was the second-line drug of choice in 64.5% of the patients unresponsive to initial IVIG treatment in a previous investigation of 5,633 patients in the United States10). A nationwide survey in Japan showed that second-line treatment with additional IVIG was performed in 44.1% of hospitals and that it was combined with other drugs in 26% of hospitals11). The rate of unresponsiveness to second-line IVIG treatment is not lower than the rate of unresponsiveness to initial IVIG treatment 12,13,14,15,16,17). Finally, the dilation of coronary arteries was significantly higher in KD patients demonstrating unresponsiveness to second-line IVIG treatment. This result suggests that such patients should be notified about the risk of unresponsiveness to additional IVIG administration before receiving it as a second-line treatment.

Because the etiology of KD is unknown, we cannot explain the pathophysiologic mechanism underlying low serum protein levels after initial IVIG treatment or its association with unresponsiveness to second-line IVIG treatment. Low serum protein levels after IVIG treatment might suggest that there is a deficient amount of serum immunoglobulin needed to alleviate illness. However, a future study verifying this assumption is needed. Other future studies should investigate the low serum protein levels as a predictor of unresponsiveness to other second-line treatments (e.g., administration of corticosteroids, infliximab, cyclosporine, methotrexate, etc.).

The most effective second-line treatment in patients with KD that are refractory to initial treatment is still unclear23). Investigations regarding the efficacy of exclusive administration of corticosteroids as the second-line treatment have shown no superior protective effect for coronary artery lesions relative to additional IVIG administration15,16,24,25). In one study, the combination of IVIG and oral prednisolone was recommended as a second-line treatment26). However, the addition of methyl prednisolone to the second-line IVIG treatment regimen was not significantly advantageous in this study. We think that the efficacy of combination therapy needs further investigation in a future study including larger numbers of patients.

This study had several limitations. First, the number of Kawasaki patients with unresponsiveness to second-line IVIG treatment was relatively small. Second, every subject in this study was Korean. Therefore, our findings should be reexamined in other ethnic groups. Third, we could not test the diameter of coronary arteries as a predictor because the initial echocardiographic examination was performed before or after initial IVIG treatment. Fourth, we have not distinguished the timing of echocardiography for the detection of coronary lesions between subacute and convalescent phase.

In conclusion, the serum protein level before second-line IVIG treatment is a significant predictor of unresponsiveness in KD patients. Furthermore, the addition of methyl prednisolone to the second-line IVIG treatment regimen in these cases is not more effective than exclusive IVIG administration.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, Gewitz MH, Tani LY, Burns JC, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1708–1733. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tremoulet AH, Best BM, Song S, Wang S, Corinaldesi E, Eichenfield JR, et al. Resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin in children with Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2008;153:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns JC, Capparelli EV, Brown JA, Newburger JW, Glode MP. Intravenous gamma-globulin treatment and retreatment in Kawasaki disease. US Canadian Kawasaki Syndrome Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:1144–1148. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199812000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sittiwangkul R, Pongprot Y, Silvilairat S, Phornphutkul C. Management and outcome of intravenous gammaglobulin-resistant Kawasaki disease. Singapore Med J. 2006;47:780–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei M, Huang M, Chen S, Huang G, Huang M, Qiu D, et al. A multicenter study of intravenous immunoglobulin non-response in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2015;36:1166–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00246-015-1138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uehara R, Belay ED, Maddox RA, Holman RC, Nakamura Y, Yashiro M, et al. Analysis of potential risk factors associated with nonresponse to initial intravenous immunoglobulin treatment among Kawasaki disease patients in Japan. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:155–160. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31815922b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koren G, Lavi S, Rose V, Rowe R. Kawasaki disease: review of risk factors for coronary aneurysms. J Pediatr. 1986;108:388–392. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80878-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichida F, Fatica NS, Engle MA, O'Loughlin JE, Klein AA, Snyder MS, et al. Coronary artery involvement in Kawasaki syndrome in Manhattan, New York: risk factors and role of aspirin. Pediatrics. 1987;80:828–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels SR, Specker B, Capannari TE, Schwartz DC, Burke MJ, Kaplan S. Correlates of coronary artery aneurysm formation in patients with Kawasaki disease. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141:205–207. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1987.04460020095035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghelani SJ, Pastor W, Parikh K. Demographic and treatment variability of refractory kawasaki disease: a multicenter analysis from 2005 to 2009. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2:71–76. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2011-00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uehara R, Yashiro M, Oki I, Nakamura Y, Yanagawa H. Re-treatment regimens for acute stage of Kawasaki disease patients who failed to respond to initial intravenous immunoglobulin therapy: analysis from the 17th nationwide survey. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:427–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashino K, Ishii M, Iemura M, Akagi T, Kato H. Re-treatment for immune globulin-resistant Kawasaki disease: a comparative study of additional immune globulin and steroid pulse therapy. Pediatr Int. 2001;43:211–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2001.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace CA, French JW, Kahn SJ, Sherry DD. Initial intravenous gammaglobulin treatment failure in Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E78. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miura M, Tamame T, Naganuma T, Chinen S, Matsuoka M, Ohki H. Steroid pulse therapy for Kawasaki disease unresponsive to additional immunoglobulin therapy. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:479–484. doi: 10.1093/pch/16.8.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furukawa T, Kishiro M, Akimoto K, Nagata S, Shimizu T, Yamashiro Y. Effects of steroid pulse therapy on immunoglobulin-resistant Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:142–146. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.126144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teraguchi M, Ogino H, Yoshimura K, Taniuchi S, Kino M, Okazaki H, et al. Steroid pulse therapy for children with intravenous immunoglobulin therapy-resistant Kawasaki disease: a prospective study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34:959–963. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki H, Terai M, Hamada H, Honda T, Suenaga T, Takeuchi T, et al. Cyclosporin A treatment for Kawasaki disease refractory to initial and additional intravenous immunoglobulin. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:871–876. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318220c3cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori M, Imagawa T, Yasui K, Kanaya A, Yokota S. Predictors of coronary artery lesions after intravenous gamma-globulin treatment in Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2000;137:177–180. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.107890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dallaire F, Dahdah N. New equations and a critical appraisal of coronary artery Z scores in healthy children. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:60–74. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim HK, Oh J, Hong YM, Sohn S. Parameters to guide retreatment after initial intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in kawasaki disease. Korean Circ J. 2011;41:379–384. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2011.41.7.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SM, Lee JB, Go YB, Song HY, Lee BJ, Kwak JH. Prediction of resistance to standard intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in kawasaki disease. Korean Circ J. 2014;44:415–422. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2014.44.6.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang JY, Lee KY, Rhim JW, Youn YS, Oh JH, Han JW, et al. Assessment of intravenous immunoglobulin non-responders in Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1088–1090. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.184101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Research Committee of the Japanese Society of Pediatric Cardiology; Cardiac Surgery Committee for Development of Guidelines for Medical Treatment of Acute Kawasaki Disease. Guidelines for medical treatment of acute Kawasaki disease: report of the Research Committee of the Japanese Society of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery (2012 revised version) Pediatr Int. 2014;56:135–158. doi: 10.1111/ped.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogata S, Bando Y, Kimura S, Ando H, Nakahata Y, Ogihara Y, et al. The strategy of immune globulin resistant Kawasaki disease: a comparative study of additional immune globulin and steroid pulse therapy. J Cardiol. 2009;53:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miura M, Ohki H, Yoshiba S, Ueda H, Sugaya A, Satoh M, et al. Adverse effects of methylprednisolone pulse therapy in refractory Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:1096–1097. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.062299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu JJ. Use of corticosteroids during acute phase of Kawasaki disease. World J Clin Pediatr. 2015;4:135–142. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v4.i4.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]