Introduction

Ophthalmia Nodosa is the term ascribed to the ocular manifestations caused by involvement of the eye by organic hair or spines of insect or vegetative origin. It is a rare condition, and most of the few case reports that exist in the literature describe affliction of the eye by caterpillar hair or setae. However, the involvement is usually of the ocular surface, which includes the lids and the conjunctiva. Intraocular involvement in the form of penetration of the cornea with projection of the seta into the anterior chamber has never been reported. We are now reporting a case of this nature, which was managed successfully.

Case report

A 28-year-adult male patient presented to us in the morning with complaints of severe pain and redness of the right eye, which developed within an hour of rubbing of the eye following the fall of a caterpillar-like insect on the eye, which occurred while he was dusting his bed sheet. On examination, the visual acuity in the right eye was 6/60 with no further improvement with pinhole. The tarsal conjunctiva of the upper lid on eversion revealed a large number of embedded caterpillar setae (Fig. 1). The conjunctiva showed ciliary congestion and the cornea revealed a large epithelial defect staining with Fluorescein inferiorly (Fig. 2). A caterpillar seta was also seen to have penetrated the cornea obliquely at the limbus at 7 O’clock position. The tip of the seta was noted to be projecting into the anterior chamber (Fig. 3). There was no anterior chamber reaction and rest of the anterior segment exam did not reveal any abnormality. Fundus exam of the eye was also normal. Visual acuity of the left eye was 6/6 and no abnormality was detected. Removal of all the visible embedded setae in the superior tarsal conjunctiva was done under slit lamp magnification using fine forceps, as each of the setae was barely 3 mm in length. The right eye was managed with topical 1% carboxymethyl cellulose drops six times a day and 0.3% topical ciprofloxacin drops four times a day. However, the patient remained symptomatic due to recurrent appearance of setae from the superior tarsus in fresh crops. This necessitated repeated removal of the setae and intermittent patching of the eye with 0.3% topical ciprofloxacin ointment. No fresh crops of setae were seen after two weeks and the epithelial defect healed completely. The patient became asymptomatic after two weeks of conservative management with the visual acuity of the affected eye improving to 6/6 unaided. However, presence of the embedded corneal seta necessitated removal, which was done thereafter in the OT with peribulbar anaesthesia through a corneal stab incision using a 20 G vitreoretinal forceps (Fig. 4). The setal tip projecting barely 0.5 mm into the anterior chamber was grasped with the forceps ab interno and extracted through the corneal stab incision. At last follow-up after 6 months, the patient was asymptomatic with 6/6 unaided vision in the affected eye.

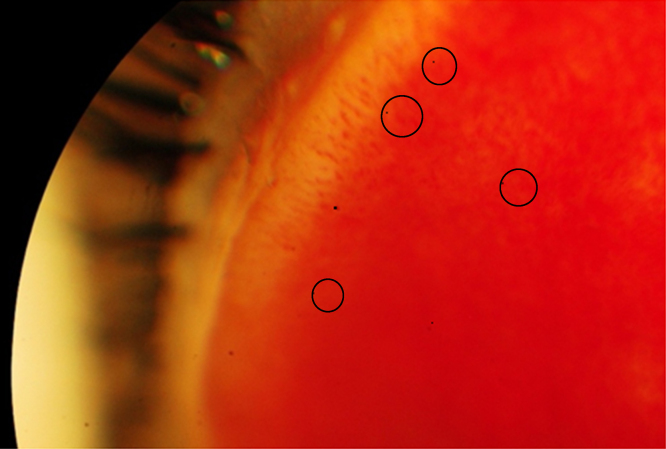

Fig. 1.

Tips of embedded setae seen protruding from the everted tarsal conjunctiva.

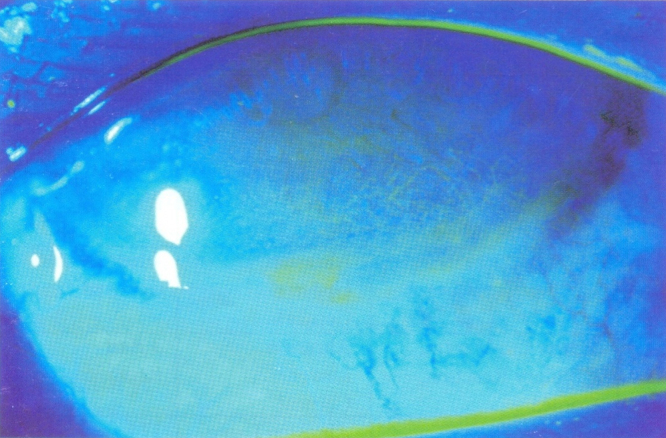

Fig. 2.

Large corneal epithelial defect seen staining with Fluorescein.

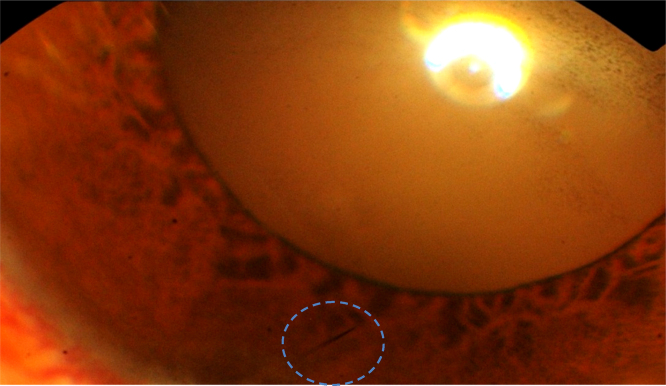

Fig. 3.

Caterpillar seta seen embedded within the cornea.

Fig. 4.

20 G vitreoretinal forceps used for extracting the embedded corneal seta ab interno.

Discussion

Ophthalmia Nodosa was first termed by Saemisch in 1904 and was initially defined as a conjunctival granulomatous reaction caused by hairs or spines of insect or vegetative origin. An article by Watson et al. in 1966 attributed most of the few cases of Ophthalmia Nodosa to caterpillars of moths of the genus Lepidoptera. The inflammatory effect of the hairs is due to the mechanical irritation as well as the proteinaceous toxin secreted by certain types of hair.1 It is an uncommon condition and has been reported sparingly in the literature. There are only a few reports from India. Cases are usually reported in the winter months when caterpillars abound, which was also the case in our patient. The initial event tends to occur indoors as the caterpillars prefer relatively dark and secluded environment to pupate, as was borne out in our case. Caterpillar setae tend to be barbed in Western reports and non-barbed, sharp and smooth in Indian ones. This explains the reason for the shorter quiescent interval for manifestation of symptoms, after the initial event, in Indian conditions. Penetration of the lids and ocular surface by setae is aided by muscular contraction of the lid muscles and rubbing of the eyelids in response to the irritation experienced by patients.2 Intraocular penetration and migration, though rare, have been postulated to be caused by globe movements and vascular and iris pulsations or due to the propulsive effect of inflammatory exudates behind the broken ends of the hair.3, 4

Caterpillar setae induced inflammation has been classified into five types: Type 1 – an acute reaction consisting of conjunctival congestion and chemosis, which starts immediately and lasts for weeks. Type 2 – chronic mechanical keratoconjunctivitis caused by caterpillar setae lodged in the bulbar or palpebral conjunctiva. Type 3 – formation of greyish yellow nodules (granulomas) in the conjunctiva. Setae may be seen in the sub-conjunctival space or may be intracorneal. Type 4 – iritis secondary to setal penetration of anterior segment. Type 5 – vitreoretinal involvement.5 Corneal penetration with intraocular involvement is a relatively rare phenomenon and has seldom been reported in Indian literature. In a case reported by Patel et al., corneal involvement was noted with two setae, one of which could be removed ab externo and one migrated inwards and caused chronic iritis.6 In a series of four cases reported by Sethi et al., one patient had an embedded corneal seta, which could not be extracted and was managed with carbolization.2 In a recent report from a premier eye institute in India, in a retrospective analysis of 544 cases of Ophthalmia Nodosa, only 80 had corneal penetration and 19 patients had intraocular involvement. Of the 80 cases with corneal penetration, removal of setae was possible only in 29 of them.7 In our patient as well, the embedded corneal seta presented a management dilemma due to the technical difficulty in its removal vis-à-vis the inadvisability of leaving it in situ due to the possibility of its acting as a tract for introducing infection into the eye. Also, there was the possibility of intraocular migration with its devastating sequelae. Keeping in mind this risk, it was decided to attempt removal of the corneal seta. As the tip of the seta was projecting by about 0.5 mm into the anterior chamber, ab interno extraction was planned. In addition to the miniscule length of the tip available for engagement, the oblique direction of entry further compounded the problem as it would be difficult to obtain a purchase on the tip, which was lying almost flush with the corneal endothelium internally. It was felt that only a vitreoretinal forceps would be delicate enough for the extraction, and accordingly the procedure was performed successfully as described earlier.

This case highlights the presentation of a rare entity at our centre and its successful management using a novel approach.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Watson P.G., Sevel D. Ophthalmia nodosa. Br J Ophthalmol. 1966;50:209–217. doi: 10.1136/bjo.50.4.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sethi P.K., Dwivedi N. Ophthalmia nodosa. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1982;30:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gundersen T., Heath P., Garron L.K. Ophthalmia nodosa. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1951:151–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ascher K.W. Mechanism of locomotion observed on caterpillar hairs. Br J Ophthalmol. 1968;52(2):210. doi: 10.1136/bjo.52.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cadera W., Pachtman M.A., Fountain J.A., Ellis F.D., Wilson F.M. Ocular lesions caused by caterpillar hair (ophthalmia nodosa) Can J Ophthalmol. 1984;19:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel R.J., Shanbhag R.M. Ophthalmia nodosa – (a case report) Indian J Ophthalmol. 1973;21:208. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sengupta S., Reddy P.R., Gyatsho J., Ravindran R.D., Thiruvengadakrishnan K., Vaidee V. Risk factors for ocular penetration of caterpillar hair in ophthalmia nodosa: a retrospective analysis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58(6):540–543. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.71711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]