Abstract

Background

To assess and compare performance of the Alvarado score and computed tomography scan in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis at King Hussein Medical Center.

Methods

A total of 320 patients with suspected acute appendicitis were included in this study over a period of 2 years. The Alvarado score was calculated for all of these patients and 112 CT scans were requested selectively by surgeons caring for the patients. The histopathology diagnosis was used as the gold standard against which diagnostic performance of Alvarado score and CT scan were compared.

Results

The complete data of 196 males and 124 females were analyzed at the end of the study period. The mean age was 26.1 ± 11.3 years. Appendectomy was performed in 263 patients with a negative appendectomy rate of 14.83% overall (12.28 in males and 19.56 in females). The remaining 57 patients were assumed to have no appendicitis. The diagnostic performance of CT scan was superior to that of Alvarado score with sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio of 94.2 versus 85.4%, 90 versus 65%, 9.42 versus 2.44, and 0.065 versus 0.224, respectively (p-value < 0.05). The overall diagnostic accuracy of CT scan was 92.6% compared to 77.5% for Alvarado score.

Conclusion

The Alvarado score was far from good and CT scan is more accurate in diagnosis of acute appendicitis in our patient population.

Keywords: Acute appendicitis, Alvarado score, Diagnostic performance

Introduction

Over the past few decades, appendectomy for acute appendicitis (AA) remained the most commonly performed emergency surgical procedure. The dictum of 1960s, ‘When in doubt, take it out,” may be no longer valid. The simplicity of the procedure has led to the ideation that it can be done by the most junior resident on call. However, the negative exploration rates have remained between 5 and 45%. The complications of surgery for AA are tremendous and can result in enormous costs notwithstanding the estimated morbidity of 10% and mortality of 2.5/1000 patients.1 On the other hand, observing a patient with a possible diagnosis of AA is refutable till the diagnosis can be ruled out. As such, many models for diagnosis of appendicitis have emerged over time with the aim of avoiding surgery in those with normal appendix including the use of serial clinical assessment, leukocyte and differential count, C-reactive protein, ultrasonography, and most recently the computed tomography (CT) scan. The Alvarado score (AS) was suggested as a composite of clinical and laboratory findings to guide management of patients with right iliac fossa pain.2 At our busy emergency department, assumption of a clinical score may be useful and cost saving, particularly with scarcity of hospital beds. The following study is aimed at validation of the AS at our hospital and comparing AS to CT scan.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in a quaternary care center serving around 4 million populations. After a thorough search of our histopathology department database, we found that approximately 1200 appendectomies were done yearly at our hospitals with around 30–40% being for a normal appendix. This has prompted our work toward reducing the negative appendectomy rate by adoption of the AS if validated at our population and by assessment of abdominopelvic CT as alternatives to clinical judgment alone. By using the Slovin's formula, we have calculated that a sample size of 320 patients would be adequate with a confidence level of 95% (i.e. margin of error of 0.05).

Over a period of 2 years from January 2014 to December 2015, 320 patients admitted with a presumptive diagnosis of AA were included in this study. Patients with diffuse peritonitis, abdominal mass, or sepsis were excluded.

Special forms that include patients’ demographic and clinical data were filled by residents and the AS was calculated for all of these patients (Table 1). Scores ≥7 were considered positive. Any additional pertinent tests performed, including imaging by US or CTS, were also recorded on these forms.

Table 1.

The Alvarado score for evaluation of suspected acute appendicitis.

| Variable | Score |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Migratory right iliac fossa pain | 1 |

| Anorexia | 1 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 1 |

| Signs | |

| Right iliac fossa tenderness | 2 |

| Rebound tenderness | 1 |

| Elevated temperature > 37.3 °C | 1 |

| Laboratory tests | |

| Leukocytosis > 10.0 × 109/L | 2 |

| Neutrophils > 75% or left shift | 1 |

Subsequent management was decided by the specialist or consultant surgeon responsible for the care for these patients not taking in consideration their initial AS. This includes performance of imaging studies, observation, or surgery. Overall, 112 patients had CT scan of the abdomen.

57 patients were discharged without intervention and these patients were called by phone, 1 month after their discharge. None of them have recurrent symptoms or had appendectomy elsewhere within this period. These patients were assumed to have no appendicitis for statistical analysis. The remaining 263 patients underwent appendectomy.

Abdomen CT scans were performed with 16-slice multidetector scanner with IV contrast and no oral contrast. 5-mm slice thickness images were obtained with lowest possible exposure factors according to body built. These were retro reconstructed to 2-mm images to obtain reasonable 3-dimensional images. CT scan was considered positive if it showed appendiceal diameter >6 mm, enhancing appendiceal wall thickening >3 mm, focal thickening of the cecum (arrowhead sign), or periappendiceal inflammatory changes (fat stranding, fluid collections, phlegmon, and abscess formation) (Fig. 1). Minimal fluid in females in the absence of appendiceal and periappendiceal changes was ignored.

Fig. 1.

CT-scan findings in acute appendicitis. (A) A 74-year old male with right iliac fossa pain. Multiplanner reformat (MPR) image of abdomen CT scan showed appendicolith with thick wall appendix and arrowhead sign (arrow). In elderly patients, CTS is mandatory to rule out cecal tumor. (B) A 26-year old male with retrocecal inflamed Appendix. In these patients, abdominal examination may be misleading. MPR image of abdomen CT scan showed a long thick wall retrocecal appendix (arrow). (C) An 18-year-old male. MPR image of abdomen CT scan shows a thick enhancing appendiceal wall with surrounding free fluid (target sign). (D) A 17-year-old female. MPR image of abdomen CT scan shows a dilated appendix with thick enhancing wall (white arrow) with enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes (black arrow).

At the end of the study period, the histopathology reports of patients who underwent surgery were reviewed. Patients whose histopathology reports revealed the presence of AA, obstructed appendix, or appendicular tumor (5 cases) were considered to have undergone therapeutic appendectomy. Those whose reports showed the presence of normal appendix, serositis, or Enterobius vermicularis in the appendix were considered to have had negative appendectomy.

The IBM SPSS 21 and the NCSS 10 were used for statistical analysis. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive-likelihood ratio (+LR), negative-likelihood ratio (−LR), and accuracy were calculated for AS and CT scan for the whole cohort and again for each gender separately. The performance of AS and CTS were compared using the NCSS 10 statistical software. A p-value <0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

Over the study period of 2 years, 320 patients with a presumptive diagnosis of AA were included in the analysis. There were 196 males and 124 females with a mean age of 26.1 ± 11.3 years. 57 patients improved without intervention and were discharged home and none of them had recurrent symptoms or appendectomy performed during a follow-up period of 1 month. The remaining 263 patients underwent appendectomy based on the judgment of the surgeon caring for them without consideration of their AS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient's demographic and clinical data and eventual management.

| Criteria | Male | Female | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 196 | 124 | 320 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 26.1 ± 9.3 | 25.6 ± 8.9 | 27.9 ± 10.8 |

| Mean duration of symptoms (range/h) | 26.7 (18–72) | 18.4 (12–60) | 22.4 (12–72) |

| WBC count (mean ± SD) | 16.4 ± 4.3 | 15.2 ± 3.6 | 15.9 ± 4.7 |

| AS (mean ± SD) | 7.53 ± 1.1 | 7.74 ± 1.1 | 7.61 ± 1.1 |

| CTS done | 49 | 63 | 112 |

| Management | |||

| No surgery | 25 | 32 | 57 |

| Therapeutic appendectomy | 150 | 74 | 224 |

| Negative appendectomy | 21 | 18 | 39 |

| Negative appendectomy rate (%) | 12.28 | 19.56 | 14.83 |

The bold entries in table show the number of CT scans performed in both genders. The negative appendectomy rate is higher in females due to the wider differential diagnosis in females particularly the gynecological causes of lower abdominal pain.

At the end of the study period, the histopathology reports of these patients revealed 224 cases of AA, obstructed appendix, or appendiceal tumor (3 carcinoids and 2 mucinous cystadenomas) giving a negative appendectomy rate of 14.83% (12.28 in males and 19.56% in females). The histopathology report results were considered the gold standard against which the calculated AS and CT scan results were evaluated.

The AS overall sensitivity and specificity were 84.96% and 59.57% respectively with a positive Likelihood ratio of 2.1 and a negative Likelihood ratio of 0.25. When the analysis was repeated for genders separately, the sensitivity and specificity of AS significantly decreased in females (Table 3). The accuracy of AS was calculated at 77.5% overall (86.7% in males versus 62.9% in females).

Table 3.

Alvarado score diagnostic performance in both genders.

| Criterion | Overall | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | 84.96 (79.62–89.35) | 87.5 | 79.7 |

| Specificity (%) | 59.57 (48.95–69.58) | 84.1 | 38 |

| Positive predictive value (%) | 83.48 (78.04–88.04) | 95 | 65.5 |

| Negative predictive value (%) | 62.22 (51.38–72.23) | 66.1 | 55.9 |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 2.1 (1.63–2.70) | 5.5 | 1.29 |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.25 (0.18–0.36) | 0.15 | 0.53 |

| Accuracy (%) | 77.5 | 86.74 | 62.9 |

On the other hand, CT scan showed significantly higher sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy that were not affected by patient's gender (Table 4).

Table 4.

CTS diagnostic performance in both genders.

| Criterion | Overall | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | 94.2 (87.75–97.83) | 93.7 | 94.9 |

| Specificity (%) | 90.0(79.49–96.24) | 90.0 | 89.5 |

| Positive predictive value (%) | 94.2 (87.75–97.83) | 96.7 | 90.2 |

| Negative predictive value (%) | 90.0 (79.49–96.24) | 94.4 | 81.8 |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 9.42 (4.40–20.15) | 9.01 | 9.37 |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.06 (0.03–0.14) | 0.07 | 0.57 |

| Accuracy (%) | 92.6 | 92.8 | 92.2 |

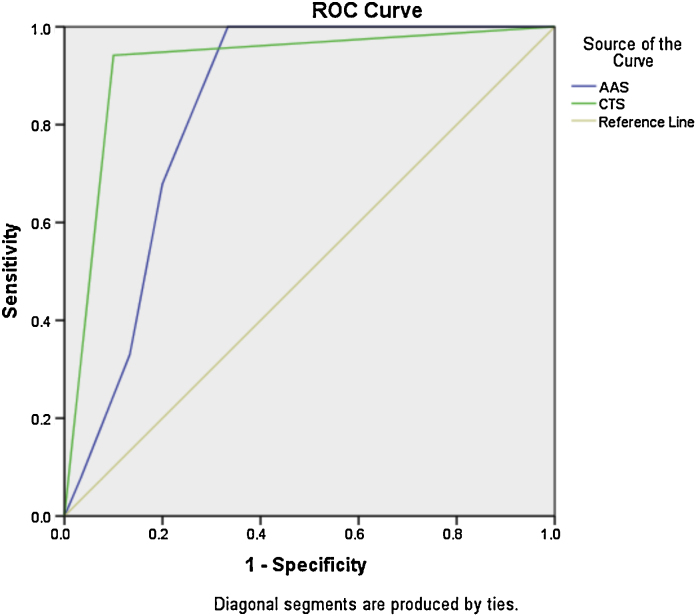

We have also compared the performance of the AS in 112 patients who have CT scan as part of their management. Using the NCSS statistical software, CT scan was superior to AS in diagnosing and ruling out AA (Table 5 and Fig. 2).

Table 5.

Comparison of the diagnostic performance of AS against CTS in 112 patients.

| Criteria | AS | CTS | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity % | 85.4 | 94.2 | 0.0382 |

| Specificity% | 65.0 | 90.0 | 0.0010 |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 2.4411 | 9.4175 | 0.0003 |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.2240 | 0.0647 | 0.0101 |

p-Value < 0.05 is statistically significant.

Fig. 2.

Area under the ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve for CTS is significantly higher than that of AS (0.921 versus 0.752, p-value 0.05).

Interestingly, in 15 patients whose AS was below 7 and their CT scan was normal, no single case of AA was diagnosed. Conversely in 67 patients with AS > 6 and positive CT scan, one patient had no appendicitis (Fig. 1d). This patient was a 26-year-old female, who was discovered to have new-onset diabetes mellitus with diabetic ketoacidosis. During management of ketoacidosis in preparation for surgery, abdominal pain was resolved and the patient was discharged without intervention.

Discussion

The AS has been suggested in 1986 aiming at reducing the frequency of negative appendectomy while allowing early appendectomy in patients with appendicitis.2 This 8-parameter score had undergone different modifications aiming at improving the performance of the score.3, 4 More recent scores such as the RIPASA (a 15-parameter score initially validated in southeast Asia) and the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR) (7-parameter score including CRP measurement) scores, although more elaborate and showing better performance than AS, are more complex and may be inconvenient in emergency department.5, 6, 7 As such, we have used the original AS, which was more widely used and evaluated, in this study.

Earlier studies on validation of AS in adults were encouraging, with sensitivity and specificity reaching 90%.8 Other studies failed to prove the benefit of AS in ruling out AA and suggested that ethnic difference may account for this.9, 10 Our results were in concordance with a similar study performed on similar population in the Middle East.11

Many of these studies, however, were before the advent of high-tech CT imaging, which is being increasingly utilized in the work-up of acute abdomen in adult population.

The use of multidetector CT scanning with postacquisition reformatting capabilities has been increasingly used in evaluation of acute abdomen. It allows visualization of the appendix, periappendiceal inflammation, and complications of appendicitis (mass, abscess, and perforation), while uncovering other alternative differential diagnoses. The disadvantages of CT scan are radiation exposure, contrast-agent toxicity, and the requirement of experienced radiologist for interpretation. A CT examination with an effective dose of 10 millisieverts may be associated with an increase in the possibility of fatal cancer of approximately 1 chance in 2000. This increase in the possibility of a fatal cancer from radiation is negligible to the natural incidence of fatal cancer in the United States population (equal to 400 chances in 2000). Many studies have shown the value of CTS in evaluation of acute abdominal pain with sensitivity of 90–100%, specificity of 91–99%, accuracies of 94–98%, PPVs of 92–98%, and NPVs of 95–100% for diagnosing AA.12, 13, 14 Our results were similar to those published in literature with an overall diagnostic accuracy of 92.6%. Recent trend toward medical management of early AA will make CTS a mandatory diagnostic test for all patients with clinical suspicion of the diagnosis.15, 16

In our study, the use of initial AS for diagnosing AA was far from good, particularly in females with an overall accuracy of 77.5%. Our results suggest that dependence on AS score alone can result in 40% negative appendectomy rate and around 15% missed appendicitis. CT scan performance was significantly better in diagnosing AA with an overall accuracy of 92.6%. The diagnostic accuracy is exaggerated when both the AS and CTS findings are taken together. When both are negative, the diagnosis of AA can be ruled out with almost 100% certainty. On the other hand, if both are positive, the chance of removing a normal appendix is negligible (1 in 67 patients in our study, 1.49%).

Laparoscopy has been suggested to replace other diagnostic studies in AA, particularly in women. However, laparoscopy will miss cases of microscopic appendicitis, may increase NARs, and is costly.17, 18, 19

In conclusion, in our settings and in our population, CTS is far superior to AS in assessment of patients with suspected appendicitis. The combination of both may even add to diagnostic accuracy as seen in our study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.SCOAP Collaborative, Cuschieri J., Florence M. Negative appendectomy and imaging accuracy in the Washington State Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. Ann Surg. 2008;248(October (4)):557–563. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318187aeca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(5):557–564. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80993-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalan M., Talbot D., Cunliffe W.J., Rich A.J. Evaluation of the modified Alvarado score in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a prospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1994;76(6):418–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamran H., Naveed D., Asad S., Hameed M., Khan U. Evaluation of modified Alvarado score for frequency of negative appendicectomies. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2010;22(October–December (4)):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong C.F., Thien A., Mackie A.J.A. Comparison of RIPASA and Alvarado scores for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Singap Med J. 2011;52(5):340–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Castro S.M.M., Ünlü Ç., Steller E.P., van Wagensveld B.A., Vrouenraets B.C. Evaluation of the appendicitis inflammatory response score for patients with acute appendicitis. World J Surg. 2012;36(7):1540–1545. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nanjundaiah N., Mohammed A., Shanbhag V., Ashfaque K., Priya S.A. A comparative study of RIPASA score and ALVARADO score in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(November (11)):NC03–NC5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9055.5170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owen T.D., Williams H., Stiff G., Jenkinson L.R., Rees B.I. Evaluation of the Alvarado score in acute appendicitis. J R Soc Med. 1992;85(2):87–88. doi: 10.1177/014107689208500211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong C.F., Adi M.I.W., Thien A. Development of the RIPASA score: a new appendicitis scoring system for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Singap Med J. 2010;51(3):220–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong V.Y., Van Der Linde S., Aldous C., Handley J.J., Clarke D.L. The accuracy of the Alvarado score in predicting acute appendicitis in the black South African population needs to be validated. Can J Surg. 2014;57(4):E121–E125. doi: 10.1503/cjs.023013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Hashemy A.M., Seleem M.I. Appraisal of the modified Alvarado Score for acute appendicitis in adults. Saudi Med J. 2004;25(September (9)):1229–1231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cağlayan K., Günerhan Y., Koç A., Uzun M.A., Altınlı E., Köksal N. The role of computerized tomography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in patients with negative ultrasonography findings and a low Alvarado score. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2010;16(September (5)):445–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee C.C., Golub R., Singer A.J., Cantu R., Jr., Levinson H. Routine versus selective abdominal computed tomography scan in the evaluation of right lower quadrant pain: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(February (2)):117–122. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.08.007. [Epub 2006 December 27] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim K., Kim Y.H., Kim S.Y. Low-dose abdominal CT for evaluating suspected appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(April (17)):1596–1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Souza N. Patients may prefer radiation risk to surgical risk in diagnosing appendicitis. BMJ. 2015;350:h3493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lahaye M.J., Lambregts D.M., Mutsaers E. Mandatory imaging cuts costs and reduces the rate of unnecessary surgeries in the diagnostic work-up of patients suspected of having appendicitis. Eur Radiol. 2015;25(May (5)):1464–1470. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akbar F., Yousuf M., Morgan R.J., Maw A. Changing management of suspected appendicitis in the laparoscopic era. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(January (1)):65–68. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12518836439920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones G.E., Kreckler S., Shah A., Stechman M.J., Handa A. Increased use of laparoscopy in acute right iliac fossa pain – is it good for patients? Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(February (2)):237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slotboom T., Hamminga J.T., Hofker H.S., Heineman E., Haveman J.W. Intraoperative motive for performing a laparoscopic appendectomy on a postoperative histological proven normal appendix. Scand J Surg. 2014;103(December (4)):245–248. doi: 10.1177/1457496913519771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]