Abstract

Cancer is a serious concern at present. A large number of patients die each year due to cancer illnesses in spite of several interventions available. Development of an effective and side effects lacking anticancer therapy is the trending research direction in healthcare pharmacy. Chemical entities present in plants proved to be very potential in this regard. Bioactive phytochemicals are preferential as they pretend differentially on cancer cells only, without altering normal cells. Carcinogenesis is a complex process and includes multiple signaling events. Phytochemicals are pleiotropic in their function and target these events in multiple manners; hence they are most suitable candidate for anticancer drug development. Efforts are in progress to develop lead candidates from phytochemicals those can block or retard the growth of cancer without any side effect. Several phytochemicals manifest anticancer function in vitro and in vivo. This article deals with these lead phytomolecules with their action mechanisms on nuclear and cellular factors involved in carcinogenesis. Additionally, druggability parameters and clinical development of anticancer phytomolecules have also been discussed.

Keywords: cancer, limitations of anticancer drugs, anticancer phytochemicals, druggability evaluation

Introduction

Cancer, a severe metabolic syndrome, is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide and the number of cases are continuously rising (Sharma et al., 2014; American Cancer Society, 2016). This disease ranks second in death cases after cardiovascular disorders in the developed nations (Mbaveng et al., 2011; Siegel et al., 2016). The cancer phenomenon is described by uncontrolled proliferation and dedifferentiation of a normal cell. Cancer cells have some marked features i.e., they tune out the signals of proliferation and differentiation, they are capable to sustain proliferation, they overcome the apoptosis, and they have power of invasion and angiogenesis. Sequential genetic alterations which produce genetic instabilities accumulate in the cell and a normal cell transforms into a malignant cell. These alterations include mutations in DNA repair genes, tumor suppressor genes, oncogenes and genes involve in cell growth & differentiation. These modifications are not just abrupt transitions but may take several years. Both external (e.g., radiations, smoking, pollution and infectious organisms) and internal factors (e.g., genetic mutations, immune conditions, and hormones) can cause cancer. Various types of cancer forms exist in human (Table 1); and the lung, breast and colorectal cancer being the most common forms (Ferlay et al., 2010). Among these the lung cancer is reported the most in men and the breast cancer in women (Horn et al., 2012). Several genes coordinate together for the growth & differentiation of a normal cell. In the cancer, one or group of these genes get altered and express aberrantly (Biswas et al., 2015). These genes can be targeted for the development of anticancer therapeutics. Modifications of epigenetic processes involved in cell growth and differentiation also lead to the development of a cancer. Therapeutic interventions which can reverse these epigenetic alterations may also be a promising option in anticancer drug discovery (Schnekenburger et al., 2014). Azacitidine, decitbine, vorinostat, and romidespin are exemplary epigenetic anticancer drugs in this regard.

Table 1.

Some epidemiological forms of cancer.

| Lung cancer | Breast cancer | Colorectal cancer |

| Lymphoma | Melanoma | Leukemia |

| Stomach cancer | Brain tumor | Prostate cancer |

| Cervical cancer | Ovary cancer | Kidney cancer |

| Liver cancer | Oral cavity cancer | Larynx cancer |

| Malignant ascites | Skin cancer | Uterus cancer |

| Pancreas cancer | Urinary bladder cancer | Thyroid cancer |

| Fibrosarcoma | Lymphosarcoma |

Drugs for cancer treatment

Cancer treatment involves surgery of tumor, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. Treatment method depends upon the stage and location of tumor. Chemotherapy involves cytotoxic and cytostatic drugs and proved to be very efficient when used in combination with other therapies. Authoritative chemotherapeutics include alkylating agents, topoisomerase inhibitors, tubulin acting agents and antimetabolites. Alkylating agents bind covalently with DNA, crosslink them and generate strand breaks. Carboplatin, cisplatin, oxaliplatin, cyclophosphamide, and melphalan are exemplary alkylating agents which work by causing such DNA damage. Doxorubicin and irinotecan are topoisomerase inhibitors and hinder DNA replication. Tubulin acting agents interrupt mitotic spindles and arrest mitosis. Paclitaxel, docetaxel, vinblastine and vincristine act on tubulins. Paclitaxel (C47H51NO14) has been proved an effective anticancer drug against most of the cancer types. It was isolated in 1967 from the endophytic fungi found in Taxus brevifolia bark (Carsuso et al., 2000). Paclitaxel targets tubulin and suppress microtubules detachment from the centrosomes. It induces multipolar divisions by forming abnormal spindles which bear additional spindle poles. This results in unnatural chromosome segregation and abnormal aneuploid daughter cells which go in apoptosis direction (Weaver, 2014). Antimetabolites stop nucleic acid synthesis and examples are methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil. Some other drugs with specific targets are also approved for the treatment of cancer. Bevacizumab inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and has been used to treat metastatic cancers (Van Meter et al., 2010). Rituximab targets CD20 in lymphoma, imatinib targets Bcr/Abl, gefitinib acts on epithelial growth factor receptor and bortezomib is approved as proteosome inhibitor (Murawski and Pfreundschuh, 2010).

Limitations of available anticancer drugs

Existing anticancer drugs target rapidly dividing cells. Several cells in our body proliferate quickly under normal circumstances, viz. bone marrow cells, digestive tract cells and hair follicle cells. So these normal cells are also affected by the above mentioned drugs and serious side effects emerge. These side effects include myelosuppression (decreased production of blood cells), mucositis (inflammation of digestive tract lining), hair loss, cardiotoxicity, neurotoxicity and immunosuppression. Additionally, rapid elimination and widespread distribution of the introduced drug to the non-targeted organs by body system requires large dose of the drug which increases above mentioned side effects and also not economic. Another limitation is the resistance of cancer cells to the available drugs. Cancer cells undergo mutations and become resistant to the introduced drugs. Therefore, given the reality of unsatisfactory chemotherapy, innovations in treating cancer with fewer side effects are the trending research direction. An ideal anticancer drug will specifically be cytotoxic toward the cancer cells only and based on the research findings, phytochemicals & derivatives present in plants are promising option for the improved and less toxic cancer therapy. Bioactive phytochemicals possess diverse therapeutic functions (e.g., analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antitumor and many more). These phytomedicines cover an important portion of our current pharmaceutics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medicinal products derived from plants.

| Drug | Pharmacological function |

|---|---|

| Aspirin | Analgesic, anti-inflammatory |

| Atropine | Pupil dilation |

| Bromelain | Anti-inflammatory |

| Colchicine | Anticancer |

| Digitoxin | Cardiotonic |

| Ginkgolides | Brain disorders |

| Harpogoside | Rheumatism |

| Hyoscyamine | Anti-cholinergic |

| Morphine | Analgesic |

| Podophyllotoxin | Anticancer |

| Quinine | Antimalarial |

| Reserpine | Anti-hypertensive |

| Salicin | Analgesic |

| Silymarin | Antihepatotoxic |

| Sitosterol | Prostate hyperplasia |

| Taxol | Anticancer |

| Vincristine and vinblastine | Anticancer |

| Tubocurarine | Mascular relaxation |

Plants as indispensable sources for anticancer phytochemicals

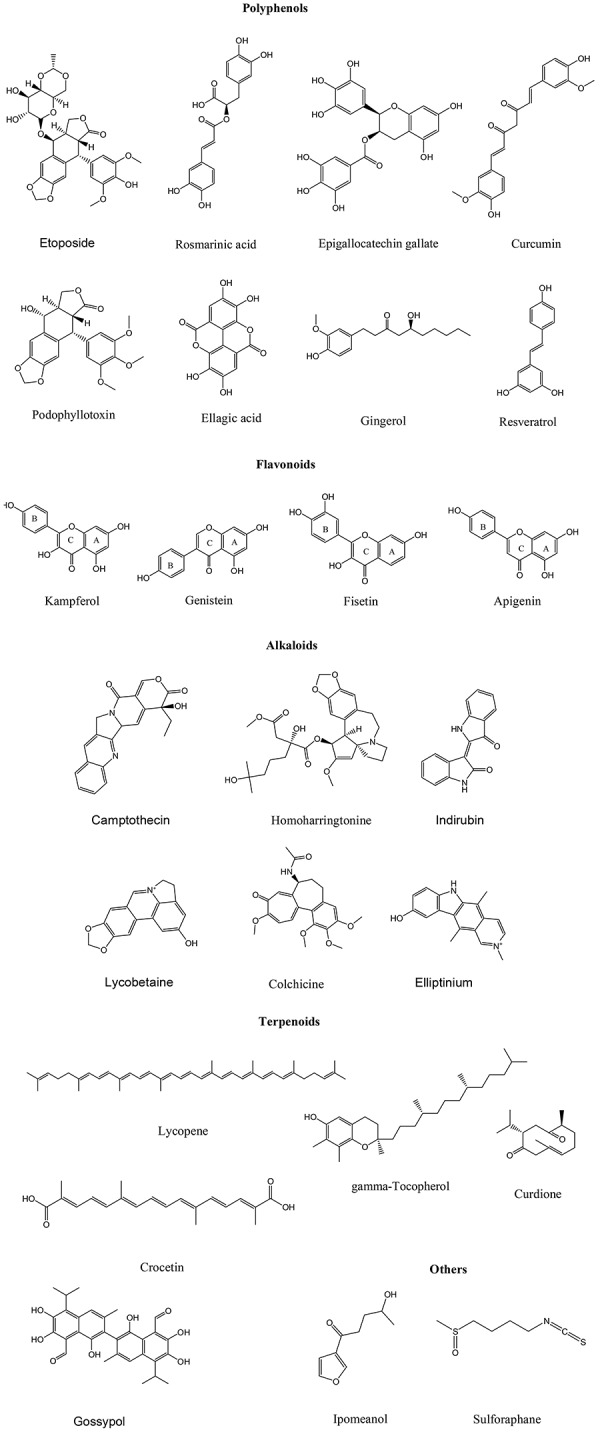

Plants and their formulations are in medicinal uses since ancient times. Various herbal preparations with different philosophies and cultural origins are used by folk medicine practitioners to heal kinds of diseases. Ayurveda, the ancient Vedic literature of India, is the science of good health and well-being (Behere et al., 2013). It is the collection of traditional and cultural philosophies to cure the diseases. Modern drug development program based on ayurveda concepts has gained wide acceptance in present healthcare system. Plant derived natural products are nontoxic to normal cells and also better tolerated hence they gain attention of modern drug discovery. Estimated figures reveal that plant kingdom comprises at least 250,000 species and only 10 percent have been investigated for pharmacological applications. Phytochemicals and their derived metabolites present in root, leaf, flower, stem and bark perform several pharmacological functions in human systems. Alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolics, tannins, glycosides, gums, resins and oils are such responsible elements (Singh et al., 2013). These elements or their altered forms have shown significant antitumor potential. Vinblastine, vincristine, taxol, elliptinium, etoposide, colchicinamide, 10-hydroxycamptothecin, curcumol, gossypol, ipomeanol, lycobetaine, tetrandrine, homoharringtonine, monocrotaline, curdione, and indirubin are remarkable phytomolecules in this regard (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of some anticancer phytochemicals.

Anticancer functions of phytochemicals on animal and cellular models

Several plant species have been discovered to suppress the progression and development of tumors in cancer patients (Umadevi et al., 2013) and many phytochemicals have been identified as active constituents in these plant species (Table 3). Phytochemicals exert antitumor effects via distinct mechanisms. They selectively kill rapidly dividing cells, target abnormally expressed molecular factors, remove oxidative stress, modulate cell growth factors, inhibit angiogenesis of cancerous tissue and induce apoptosis. For example some polyphenols (e.g., resveratrol, gallocatechins), flavonoids (e.g., methoxy licoflavanone, alpinumisoflavone), and brassinosteroids (e.g., homocatasterone and epibrassinolide) exert anticancer effects through apoptosis induction (Heo et al., 2014; Wen et al., 2014). Curcumin, thymol, rosmarinic acid, β-carotene, quercetin, rutin, allicin, gingerol, epigallocatechin gallate, and coumarin perform anticancer functions through antioxidant mechanisms.

Table 3.

Phytochemicals which demonstrated effective tumor killing in various cancer types.

| Phytochemical(s) | Cancer models suppressed | References |

|---|---|---|

| Alexin B, Emodin (Aloe vera) | Leukemia, stomach cancer, neuroectodermal tumors | Elshamy et al., 2010 |

| Allylmercaptocysteine, allicin (Allium sativum) | Colon cancer, bladder carcinoma | Ranjani and Ayya, 2012 |

| Amooranin (Amoora rohituka) | Breast, cervical, and pancreatic cancer | Chan et al., 2011 |

| Andrographolide (Andrographis paniculata) | Cancers of breast, ovary, stomach, prostate, kidney, nasopharynx malignant melanoma, leukemia | Geethangili et al., 2008 |

| Ashwagandhanolide (Withania somnifera) | Cancers of breast, stomach, colon, lung, and central nervous system | Yadav et al., 2010 |

| Bavachanin, corylfolinin, psoralen (Psoralea corylifolia) | Cancers of lung, liver, osteosarcoma, malignant ascites, fibrosarcoma, and leukemia | Wang et al., 2011 |

| Berberine, Cannabisin-G (Berberis vulgaris) | Cancers of breast, prostate, liver, and leukemia | Elisa et al., 2015 |

| Betulinic acid (Betula utilis) | Melanomas | Król et al., 2015 |

| Boswellic acid (Boswellia serrata) | Prostate cancer | Garg and Deep, 2015 |

| Costunolide, Cynaropicrine, Mokkolactone, (Saussurea lappa) | Intestinal cancer, malignant lymphoma, and leukemia | Lin et al., 2015 |

| Curcumin (Curcuma longa) | Cancers of breast, lung, esophagus, liver, colon, prostate, skin and stomach | Perrone et al., 2015 |

| Daidzein and genistein (Glycine max) | Cancers of breast, uterus, cervix, lung, stomach, colon, pancreas, liver, kidney, urinary bladder, prostate, testis, oral cavity, larynx, and thyroid | Li et al., 2012 |

| Damnacanthal (Morinda citrifolia) | Lung cancer, sarcomas | Aziz et al., 2014 |

| β-Dimethyl acryl shikonin, arnebin (Arnebia nobilis) | Rat walker carcinosarcoma | Thangapazham et al., 2016 |

| Emblicanin A & B (Emblica officinalis) | Cancers of breast, uterus, pancreas, stomach, liver, and malignant ascites | Dasaroju and Gottumukkala, 2014 |

| Eugenol, orientin, vicenin (Ocimum sanctum) | Cancers of breast, liver, and fibrosarcoma | Preethi and Padma, 2016 |

| Galangin, pinocembrine, acetoxy chavicol acetate (Alpinia galangal) | Cancers of lung, breast, digestive systems, prostate, and leukemia | Sulaiman, 2016 |

| Gingerol (Zingiber officinale) | Cancers of ovary, cervix, colon, rectum, liver, urinary bladder, oral cavity, neuroblastoma, and leukemia | Rastogi et al., 2015 |

| Ginkgetin, ginkgolide A & B (Ginkgo biloba) | Glioblastoma multiforme, hepatocarcinoma, ovary, prostate, colon, and liver | Xiong et al., 2016 |

| Glycyrrhizin (Glycyrrhiza glabra) | Lung cancer, fibrosarcomas | Huang et al., 2014 |

| Gossypol (Gossypium hirsutum) | Cancers of breast, esophagus, stomach, liver, colon, pancreas, adrenal gland, prostate, urinary bladder, malignant lymphoma & myeloma, brain tumor, and leukemia | Zhan et al., 2009 |

| Kaempferol galactoside (Bauhinia variegata) | Cancers of breast, lung, liver, oral cavity, larynx, and malignant ascites | Tu et al., 2016 |

| Licochalcone A, Licoagrochalcone (Glycyrrhiza glabra) | Cancers of prostate, breast, lung, stomach, colon, liver, kidney, and leukemia | Zhang et al., 2016 |

| Lupeol (Aegle marmelos) | Breast cancer, lymphoma, melanoma, and leukemia | Wal et al., 2015 |

| Nimbolide (Azadirachta indica) | Colon cancer, lymphoma, melanoma, leukemia, and prostate cancer | Wang et al., 2016 |

| Panaxadiol, panaxatriol (Panax ginseng) | Cancers of breast, ovary, lung, prostate, colon, renal cell carcinoma, leukemia, malignant lymphoma, and melanoma | Du et al., 2013 |

| Plumbagin (Plumbago zeylanica) | Cancers of breast, liver, fibrosarcoma, leukemia, and malignant ascites | Yan et al., 2015 |

| Podophyllin & podophyllotoxin (Podophyllum hexandrum) | Cancers of breast, ovary, lung, liver, urinary bladder, testis, brain, neuroblastoma, and Hodgkin's disease | Liu et al., 2015 |

| Psoralidin (Psoralea corylifolia) | Stomach and prostate cancer | Pahari et al., 2016 |

| Sesquiterpenes and diterpenes (Tinospora cordifolia) | Lung, cervix, throat, and malignant ascites | Gach et al., 2015 |

| 6-Shogaol (Zingiber officinale) | Ovary cancer | Ghasemzadeh et al., 2015 |

| Skimmianine (Aegle marmelos) | Liver tumors | Mukhija et al., 2015 |

| Solamargine, solasonine (Solanum nigrum) | Cancers of breast, liver, lung, and skin | Al Sinani et al., 2016 |

| Thymoquinone (Nigella sativa) | Colon, breast, prostate, pancreas, uterus, malignant lymphoma, ascites, melanoma, and leukemia | Fakhoury et al., 2016 |

| Ursolic acid and oleanolic acid (Prunella vulgaris) | Cancers of breast, cervix, lung, oral cavity, esophagus, stomach, colon, thyroid, malignant lymphoma, intracranial tumors, and leukemia | Wozniak et al., 2015 |

| Ursolic acid (Oldenlandia diffusa) | Cancers lung, ovary, uterus, stomach, liver, colon, rectum, brain, lymphosarcoma, and leukemia (Al Sinani et al., 2016) | Wozniak et al., 2015 |

| Vinblastine, vincristine (Catharantus roseus) | Cancers of breast, ovary, cervix, lung, colon, rectum, testis, neuroblastoma, leukemia, rhabdomyosarcoma, malignant lymphoma, and hodgkin's disease | Keglevich et al., 2012 |

| Viscumin, digallic acid (Viscum album) | Cancers of breast, cervix, ovary lung, stomach, colon, rectum, kidney, urinary bladder, testis, fibrosarcoma, melanoma | Bhouri et al., 2012 |

| Withaferin A, D (Withania somnifera) | Cancers of breast, cervix, prostate, colon, nasopharynx, larynx, and malignant melanoma | Lee and Choi, 2016 |

Anticancer drug development involves in vitro cytotoxicity on cancer cells, in vivo confirmation, and clinical trial evaluation. Assessment of cytotoxicity toward cancer cell lines is a trending strategy for the discovery of anticancer agents. Cell viability assessment of cancer cells is a high throughput screening method through which numerous compounds can be screened in a short period of time. Several such phytochemicals have been discovered from plants and dietary supplements (Table 4). Crude phytochemical extracts also suppress the viability of cancer cells (Table 5).

Table 4.

Phytochemicals which are cytotoxic against cancer cell lines.

| Phytochemical(s) | Cell line | References |

|---|---|---|

| Actein (Actaea racemosa) | HepG2 (liver cancer), MCF7 (breast cancer) | Einbonda et al., 2009 |

| β-Aescin (Aesculus hippocastanum) | HT29 (colorectal adenocarcinoma) | Zhang et al., 2010 |

| Allylmercaptocysteine, allicin (Allium sativum) | HeLa (cervix cancer), L5178Y (lymphoma), MCF7 | Karmakar et al., 2011 |

| Amooranin (Amoora rohituka) | MCF7, CEM (lymphocytic leukemia) | Chan et al., 2011 |

| Asiatic acid (Centella asiatica) | EAC (ehrlich ascites carcinoma), DLA (dalton's lymphoma ascites), SK-MEL-2 (melanoma), U-87-MG (glioblastoma), B16F1 (melanoma), MDA-MB-231 (breast adenocarcinoma) | Heidari et al., 2012 |

| Baicalein (Scutellaria baicalensis) | LXFL-529L (lung cancer) | Zhou et al., 2008 |

| Carnosic acid, rosmarinic acid (Rosmarinus officinalis) | A549 (lung cancer), SMMC7721 (liver cancer), A2780 (ovary cancer) | Tai et al., 2012 |

| β-Caryophyllene, α-zingiberene (Peristrophe bicalyculata) | MCF7, MDA-MB-468 | Ogunwande et al., 2010 |

| Cinnamaldehyde (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) | HeLa, HCT116 (colorectal carcinoma), HT29 | Koppikar et al., 2010 |

| Clausenalansamide A and B (Clausena lansium) | SGC-7901 (gastric cancer), HepG2, A549 | Maneerat et al., 2011 |

| Corydine, salutaridine (Croton macrobotrys) | NCI-H460 (lung cancer), K5662 (leukemia) | Motta et al., 2011 |

| Conyzapyranone A and B (Conyza Canadensis) | HeLa, A431 (epidermoid carcinoma), MCF7 | Csupor-Loffler et al., 2011 |

| Costunolide, tulipinolide, liriodenine, germacranolide (Liriodendron tulipifera) | KB (oral cancer), HT29 | Wang et al., 2012 |

| Crocin, picrocrocin, crocetin, and safranal (Crocus sativus) | S-180 (sarcoma), EAC, DLA, Tca8113 (oral cancer), and HCT116 | Bakshi et al., 2009 |

| Dioscin (Dioscorea colletti) | HepG2, SGC-7901 | Hu et al., 2011 |

| Epicatechin, procyanidin B2, B4 (Litchi cinensis) | MCF7 | Bhoopat et al., 2011 |

| Gallic acid (Leea indica) | EAC | Raihan et al., 2012 |

| Harringtonines (Cephalotaxus harringtonia) | P388 (blood cancer), L-1210 (blood cancer) | Jin et al., 2010 |

| Hydroxycinnamoyl ursolic acid (Vaccinium macrocarpon) | MCF7, ME180 (cervical cancer), and PC3 (prostate cancer) | Kondo et al., 2011 |

| Leachianone A (Radix sophorae) | HepG2 | Long et al., 2009 |

| Lectin (Hibiscus mutabilis) | HepG2, MCF7 | Lam and Ng, 2009 |

| Naphthoquinones (Tabebuia avellanedae) | EAC, DU145 (prostate cancer) | Yamashita et al., 2009 |

| Niazinine A (Moringa oliefera) | AML (blood cancer), HepG2 | Khalafalla et al., 2011 |

| Pectolinarin (Cirsium japonicum) | S180, H22 (liver cancer) | Yin et al., 2008 |

| Piperine, piperidine (Piper nigrum) | B16F10 (melanoma) | Liu et al., 2010 |

| Platycodin D (Platycodon grandiflorum) | A549, HT29 | Shin et al., 2009 |

| Plumbagin (Plumbago zeylanica) | PC3, A549, NB4 (blood cancer), A375 (skin cancer), SGC7901 | Checker et al., 2010 |

| Pyrogallol (Emblica officinalis) | L929 | Baliga and Dsouza, 2011 |

| Tylophorine (Tylophora indica) | A549, DU145, ZR751 (breast cancer) | Kaur et al., 2011 |

| Withaferin A (Withania somnifera) | MCF7, MDA-MB-231 | Hahm et al., 2011 |

Table 5.

Plants whose phytochemical preparation is cytotoxic toward cancer cell lines.

| Plant | Cancer cell line(s) | GI50 (μg/ml)# | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abelia triflora (leaf) | A549 | 1000 | Al-Taweel et al., 2015; Rafshanjani et al., 2015 |

| Abutilon indicum (leaf) | A549 | 85.2 | Kaladhar et al., 2014 |

| Amphipterygium adstringens (bark) | OVCAR3 (ovary adenocarcinoma) | Garcia et al., 2015 | |

| Annona crassiflora and A. coriacea (leaf and seed) | UA251 (glioma), UACC62 (lymphoid melanoma), MCF7, NCIH460 (lung cancer), 786-0 (renal carcinoma), HT29, NCIADR-RES (ovary cancer), OVCAR, K562 (myeloid leukemia) | ≈8.9 | Formagio et al., 2015 |

| Argemone gracilenta | M12.C3F6 (B-cell lymphoma) RAW264.7 (leukemia) HeLa |

46.2 64.45 78.87 |

Leyva-Peralta et al., 2015 |

| Camellia sinensis (black tea) | MCF-7 | 0.0125 | Konariková et al., 2015 |

| Catharanthus roseus Emblica officinalis (fruit) | HCT116 | 46.21 35.21 |

Bandopadhyaya et al., 2015 |

| Centaurea kilaea | MCF7 HeLa PC3 |

60.7 53.07 73.92 |

Selvarani et al., 2015; Sen et al., 2015 |

| Chamaecyparis obtuse (leaf) | HCT116 | 1.25 | Kim et al., 2015 |

| Chresta sphaerocephala (leaf and stem) | OVCAR3 786-0 U251 |

50.4 72.3 77.6 |

Da Costa et al., 2015 |

| Cichorium intybus | MCF7 | 429 | Gospodinova and Krasteva, 2015 |

| Croton sphaerogynus (leaf) | U251, MCF7, NCIH460 | – | dos Santos et al., 2015 |

| Curcuma longa (rhizome) | A549 | 207.3 | Shah et al., 2015 |

| Elaeocarpus serratus (leaf) | MCF7 | 227 | Sneha et al., 2015 |

| Fraxinus micrantha | MCF7 | 18.95 | Kumar and Kashyap, 2015 |

| Harpophyllum caffrum (leaf) | HCT116 A549 MCF7 HepG2 |

29 28.8 21 29 |

El-Hallouty et al., 2015 |

| Holarrhena floribunda (leaf) | MCF7 HT29 HeLa | 126.7 159.4 106.7 |

Badmus et al., 2015 |

| Ipomoea quamoclit (leaf) | CNE1 (nasopharynx carcinoma) HT29 MCF7 HeLa |

18 18 31 33 |

Ho et al., 2015 |

| Ipomoea pestigridis (leaf) | HepG2 | 155.2 | Begum et al., 2015; Kabbashi et al., 2015 |

| Justicia tranquibariensis (roots) | HeLa | >200 | Jiju, 2015; Nair et al., 2015 |

| Nardostachys jatamansi (roots and rhizome) | MCF7 MDA-MB-231 |

58.01 23.83 |

Chaudhary et al., 2015 |

| Piper cubeba (seed) | MCF7 MDA-MB-468 |

22.31 21.84 |

Graidist et al., 2015 |

| Piper pellucidum (leaf) | HeLa | 2.85 | Wahyu et al., 2013 |

| Premna odorata (bark) | HCT116 MCF7 A549 AA8 |

8.58 8.42 11.42 18.09 |

Tantengco and Jacinto, 2015 |

| Psidium guajava (leaf) | EAC HeLa MDA-MB-231 MG-263 |

25 49.5 6.19 6.19 |

Shakeera and Sujatha, 2015 |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | C6 (glioma), MCF, T47D (breast cancer), A549 | - | Bhat et al., 2015 |

| Rubus fairholmianus (root) | Caco2 | 20 | George et al., 2015 |

| Sansevieria liberica (root) | HeLa HCT116 THP1 (leukemia) |

23 22 18 |

Akindele et al., 2015 |

| Sideritis syriaca (leaf) | MCF7 | 100 | Yumrutas et al., 2015 |

| Solanum nigrum | HeLa SiHa (cervix carcinoma) C33A (cervix carcinoma) | 250 87.5 100 |

Paul et al., 2015 |

| Theobroma cacao (leaf) | MCF7 | 41.4 | Baharum et al., 2014 |

| Trapa acornis (shell) | SKBR3 (breast cancer) MDA-MB-435 |

56.07 31.60 |

Pradhan and Tripathy, 2014 |

| Tridax procumbens | A549, HepG2 | - | Priya and Srinivasa, 2015 |

| Triumfetta welwitschii | Jurkat T cells (T-cell leukemia) | – | Batanai and Stanley, 2015 |

| Vernonia amygdalina (leaf) | HL60 SMMC7721 A549 MCF7 SW480 (colorectal adenocarcinoma) |

5.58 8.74 10.97 9.51 8.84 |

Iweala et al., 2015 |

| Vinca major (aerial parts) | HEp-2 (HeLa derived) | 228 | Singh et al., 2014 |

Concentration of plant preparation at which 50% growth inhibition of cells found.

Molecular targets and mechanisms of action of anticancer phytochemicals

The exact mechanism by which phytochemicals perform anticancer functions is still a topic of research. They exert wide and complex range of actions on nuclear and cytosolic factors of a cancer cell. They can directly absorb the reactive oxygen species (ROS) or promote activities of antioxidant enzymes (e.g., superoxide dismutase, glutathione and catalase) in a transformed cell. A phytomolecule can suppress malignant transformation of an initiated pre-neoplastic cell or it can block the metabolic conversion of the pro-carcinogen. Also, they can modulate cellular and signaling events involved in growth, invasion and metastasis of cancer cell. Ellagic acid of pomegranate induces apoptosis in prostate and breast cancer cells, and inhibits metastasis processes of various cancer types. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) suppresses the activity of ornithine decarboxylase, the enzyme which signals the cell to proliferate faster and bypass apoptosis. Luteolin obstructs epithelial mesenchymal transition. Flavanones, isoflavones and lignans prevent binding of the estrogen to the cancer cells and reduce their proliferation. Reduction of inflammation processes through suppression of nuclear factor- kappa B (NF-κB) family transcription factors is an additional mechanism. Curcumin, bilberries anthocyanins, EGCG, caffeic acid and derivatives and quercetin act via NF-κB signaling. Besides these mechanisms, anticancer phytomolecules targets several other signaling molecules/ pathways also to reduce the growth and metastasis of cancer cells.

Apigenin, the flavone found in parsley, celery, and chamomile targets leptin/leptin receptor pathway and induces apoptosis in lung adenocarcinoma cells. It induces caspase dependent extrinsic apoptosis in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) over expressing BT-474 breast cancer cells through inhibition of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling (Seo et al., 2015). Curcumin, the polyphenol of Curcuma longa slows down the growth of human glioblastoma cells by modulating several molecular components. It upregulates the expressions of p21, p16, p53, early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1), extracellular signal regulated kinase (Erk), c-Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK), ElK-1 (member of ETS oncogenic family), Bcl-2 associated X protein (Bax) and Caspase- 3, 8, 9 proteins; and downregulates the levels of B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), p65, B cell lymphoma extra-large protein (Bcl-xL), protein kinase B (Akt), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), NF-κB, cell division cycle protein 2 (cdc-2), retinoblastoma protein (pRB), cellular myelocytomatosis oncogenes (c-myc) and cyclin D1 proteins (Vallianou et al., 2015).

Crocetin, the carotenoid present in Crocus sativus and Gardenia jasminoides act on GATA binding protein 4 and MEK-ERK1/2 pathway and protect against cardiac hypertrophy (Cai et al., 2009). Cyanidin glycosides from red berries execute antioxidant and anticancer functions through various mechanisms. In colon cancer cells, they suppress the expressions of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) genes and inhibit mitogen induced metabolic pathways (Serra et al., 2013). In human vulva cells, they target EGFR and in breast cancer cells they block the ErbB2/cSrc/FAK pathway and prevent their metastasis (Xu et al., 2010). EGCG, the catechin polyphenol of tea exert anticancer effects through multiple mechanisms. It blocks NF-κB activation, Bcl-2 and COX-2 expression in prostate carcinoma cells and induces apoptosis. In bladder and lung carcinoma cells, it inhibits matrix metallopeptidase-9 (MMP-9) expression (Singh et al., 2011). In head & neck carcinoma cells it suppresses the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In fibrosarcoma cells it prevents the Erk phosphorylation and activity of MMP-2 & 9. And, in gastric carcinoma cells it suppresses the Erk, JNK, and MMP-9 expressions (Luthra and Lal, 2016).

Fisetin and hesperetin cause cell cycle arrest in human acute promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells by altering several signaling networks, viz. mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK), NF-κB, JAK/STAT, PI3K/Akt, Wnt, and mTOR pathways (Adan and Baran, 2015). Genistein, the isoflavone of soybean exerts its anticancer effects via inhibition of NF-κB and Akt signaling pathways (Li et al., 2012). Gingerol targets the Erk1/2/JNK/AP-1 signaling and induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in colon cancer cells (Radhakrishnan et al., 2014). Kaempferol acts on proto-oncogene tyrosine protein kinase (Src), Erk1/2 and Akt pathways in pancreatic cancer cells and retard their growth & migration (Lee and Kim, 2016). Similarly, lycopene targets PI3K/Akt pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. It prevents gastric carcinogenesis by inhibiting Erk and Bcl-2 signaling (Kim and Kim, 2015). It activates antioxidant enzymes (e.g., GST, GSH, and GPx) in the cancer cells and removes oxidative damage produced by the carcinogen. Rosmarinic acid reduces COX-2 activity and Erk phosphorylation in colon cancer cells (Hossan et al., 2014). In breast cancer cells, rosmarinic acid reduces the activity of DNA methyl transferase and interfere RANKL/RANK/OPG networks. Also, it targets PKA/CREB/MITF pathway and NF-κB activation in melanoma and leukemia U938 cells respectively (Hossan et al., 2014).

Calcitriol inhibits prostaglandins, COX-2, NF-κB, and VEGF signaling and prevents angiogenesis of cancer cells (Diaz et al., 2015). Tocotrienols and γ-tocopherol hinder PI3K/Akt and Erk/MAPK pathways (Sylvester and Ayoub, 2013). Colchicine upregulates dual specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1) gene in gastric carcinogenesis (Lin et al., 2016). It also prevents the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through upregulation of A-kinase anchoring protein 12 (AKAP12) and transforming growth factor beta-2 (TGF-β2) proteins (Kuo et al., 2015). Podophyllotoxin blocks the growth of MCF-7 breast cancer cells by altering checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk-2) signaling pathway (Zilla et al., 2014). Podophyllotoxin also promotes apoptosis in non-small cell lung carcinoma cells through ER stress, autophagy and cell cycle arrest (Choi et al., 2015). Vinblastine and taxol target activator protein 1 (AP-1) signaling pathways (Flamant et al., 2010). Resveratrol arrest carcinogenesis by multiple mechanisms, viz. upregulation of p53 and BAX proteins and downregulation of NF-κB, AP-1, hypoxia induced factor 1α (HIF-1α), MMPs, Bcl-2, cytokines, cyclins, cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs) and COX-2 proteins (Varoni et al., 2016).

These phytomolecules act on epigenetic elements also. DNA methylation, histone modifications and miRNAs expression are important epigenetic processes which involve in cancer initiation and progression. Phytomolecules reduce the activities and expression of DNA methyl transferases (DNMTs), histone deacetylases (HDACs) and histone methyl transferases (HMTs) and increase promoter demethylation in various cancer models (Thakur et al., 2014).

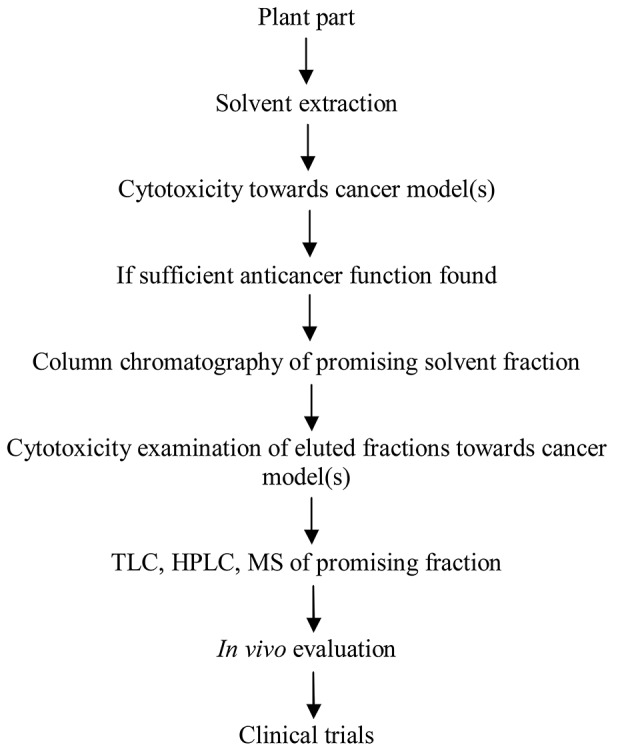

Process development for purification of anticancer phytochemicals

Therapeutic efficacy of any medicinal plant depends upon the quality and quantity of the active phyto-constituent(s), which vary with latitude, altitude, climate and season. Different parts of a plant may possess different level of pharmacological activity. Additive or synergistic effects of bioactive phyto-constituents might be responsible for the concerned pharmacological function rather than the purified one. These bioactive phyto-constituents can be developed in antitumor therapeutic entities but they demand intense effort. Several approaches can be used to purify these pharmacologically active phytochemicals. These include isolation and assay, combinatorial chemistry and bioassay-guided fractionation. Bioassay guided fractionation involves the separation of bioactive phytochemicals from a mixture of compounds using various analytic techniques based on biological activity testing. The process begins with the testing of natural extract with the confirmed bioactivity. The active extract is fractionated on suitable matrices, eluted fractions are tested for bioactivity and active fractions are examined by various analytic techniques, viz. thin layer chromatography (TLC), HPLC, FTIR, and Mass spectroscopy (MS). This approach can also be used to purify antimicrobial, antilipolytic and antioxidant compounds (Figure 2). Solvents should be used in an increasing polarity order. Silica, Sephadex, Superdex, or any other suitable matrix can be used for fractionation. Vanilline-sulfuric acid can be used as dyeing reagent for the detection natural compounds. The procedures may be modified but purity and quantity of the bioactive molecule must be high as much as possible and this can be achieved by using good quality of solvents, experimental careful handling and efficiency of the procedure. After purification, molecule(s) must be examined in vivo for the anticancer effects. If a promising tumor killing is achieved by the molecule then other parameters i.e., safety and adverse effects, dose concentration, pharmacokinetics, drug interactions etc. must be explored for the drug molecule.

Figure 2.

Development of the bioactive phytomolecule(s) into an anticancer product.

Druggability evaluation of natural products

Bioactive functional leads of natural origins can be used as original or must be converted into the druggable forms. Outrageous cost and reduced number of new drug approvals are serious challenges to the new drug discovery. The major task in plant-based drug discovery is the selection of right candidate species of pharmacological activity. This identification can be achieved using several approaches, viz. random selection, ethnopharmacology, codified systems of medicine, ayurvedic classical texts or zoopharmacognosy. Analysis of ayurvedic attributes of ancient healing formulations for the initial selection and bioactivity guided fractionation of the identified plant is a strategy of worth with greater success rate and reduced cost, time, and toxicity parameters. The Bhavprakash is an important ayurvedic text for the cancer prevention. The botanic candidate can be selected on the basis of ethnomedicine uses also. These plant species can be safer than the species with no history of human use. Another challenge with plant based medicinal products is their poor bioavailability due to excessive degradation by drug metabolic enzymes. The chemical entities of plants have greater steric complexity, greater number of chiral centers, greater number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, diverse in aromaticity and higher molecular mass and rigidity which pose strings of challenges in their development into a clinical product.

Therapeutic phytomolecules and dietary supplements of natural origins are governed by Food and Drug Administration (FDA, USA) and Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act 1994 respectively for their pharmacological effects and safety issues. Despite having desired bioactivity and ADMET profile (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity), most of the chemical entities of natural origin do not fulfill Lipinski's “rule of five” the drug likeness criteria according to which, a candidate should have less than 500 Da molecular weight, less than 5 hydrogen bond donors, less than 10 hydrogen bond acceptors and less than 5 partition coefficient (logP) for being work as a drug molecule. These rules are aimed to achieve highest bioavailability. Nonetheless some breakthrough natural products for e.g., paclitaxel would have never become a drug based on these Lipinski's conventions. So there is an essential need to develop suitable druggability standards for the compounds/formulations of natural origins. Various coating materials, micelles, liposomes, phospholipid complexes and nano-materials may be used to enhance the bioavailability of phytomedicines.

Conclusion

The world is moving toward natural products due to their low cost and reliability over side effects resulted from existing drugs. Researchers are intensifying their efforts for the development of phytopharmaceuticals against severe metabolic syndromes including cancer. Bioactive phytochemicals/formulations are potential leads for the development of safer anticancer drugs. Several plants and their constitutive phytochemicals have been screened for this purpose but only a very few have reached up to the clinical level. Anticancer phytochemicals described in this article must be further researched in clinical trials for their effectiveness and toxicological documentation. They must be developed as druggable forms with sufficient bioavailability. Moreover, we know that a traditional herbal preparation has greater medicinal effect than the same phytochemical/molecule taken in a pure form. So therapeutic intervention based upon the combination of anticancer molecules may give potent and effective therapeutic results.

India is the largest producer of medicinal plants and many of the current health care products. Substantial scientific work has been done on Indian plants and their products for the treatment of frightful diseases. They must be explored for anticancer potential. Furthermore, medicinal attributes put the medicinal plants in high demand and draw the attention of world in risking their biodiversity. Due to increasing demand and deforestation, over exploitation of the medicinal plants continues worldwide with time. Thus, some of the medicinal plants may become extinct soon. Therefore, medicinal plants need their conservation also. Germplasm preservation, viable seed preservation and cryopreservation are promising strategies for the same. In final words, this review can help healthcare pharmacy to explore values of medicinal plants to treat malignancies.

Author contributions

All authors listed, have made substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Govt. of India to SS (Grant No. DBT-JRF/F-19/487) till March 2016 is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Adan A., Baran Y. (2015). The pleiotropic effects of fisetin and hesperetin on human acute promyelocytic leukemia cells are mediated through apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and alterations in signaling networks. Tumor Biol. 36, 8973–8984. 10.1007/s13277-015-3597-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akindele A. J., Wani Z. A., Sharma S., Mahajan G., Satti N. K., Adeyemi O. O., et al. (2015). In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of root extracts of Sansevieria liberica Gerome and Labroy (Agavaceae). Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 1–11. 10.1155/2015/560404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Sinani S. S., Eltayeb E. A., Coomber B. L., Adham S. A. (2016). Solamargine triggers cellular necrosis selectively in different types of human melanoma cancer cells through extrinsic lysosomal mitochondrial death pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 16, 11. 10.1186/s12935-016-0287-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Taweel A. M., Perveen S., Fawzy G. A., Ibrahim G. A., Khan A., Mehmood R. (2015). Cytotoxicity assessment of six different extracts of Abelia triflora leaves on A-549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 16, 4641–4645. 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.11.4641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society (2016). Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz M. Y., Omar A. R., Subramani T., Yeap S. K., Ho W. Y., Ismail N. H., et al. (2014). Damnacanthal is a potent inducer of apoptosis with anticancer activity by stimulatin p53 and p21 genes in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 7, 1479–1484. 10.3892/ol.2014.1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badmus J. A., Ekpo O. E., Hussein A. A., Meyer M., Hiss D. C. (2015). Antiproliferative and apoptosis induction potential of the methanolic leaf extract of Holarrhena floribunda (G Don). Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 1–11. 10.1155/2015/756482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baharum Z., Akim A. M., Taufiq-Yap Y. H., Hamid R. A., Kasran R. (2014). In vitro antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of methanolic plant part extracts of Theobroma cacao. Molecules 19, 18317–18331. 10.3390/molecules191118317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi H. A., Sam S., Anna F., Zeinab R., Ahmad S. G., Sharma M. (2009). Crocin from Kashmiri Saffron (Crocus sativus) Induces in vitro and in vivo xenograft growth inhibition of Dalton's lymphoma (DLA) in Mice. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 10, 887–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliga M. S., Dsouza J. J. (2011). Amla (Emblica officinalis Gaertn), a wonder berry in the treatment and prevention of cancer. Euro. J. Cancer Prev. 20, 225–239. 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32834473f4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandopadhyaya S., Ramakrishnan M., Thylur R. P., Shivanna Y. (2015). In-vitro evaluation of plant extracts against colorectal cancer using HCT 116 cell line. Int. J. Plant Sci. Ecol. 1, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Batanai M., Stanley M. (2015). Antiproliferative activity of T welwitschii extract on Jurkat T cells in vitro. Biomed Res. Int. 2015:817624. 10.1155/2015/817624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum S. S., Ajithadhas A., Sivakumar T., Premanand C., Sribhuaneswari (2015). In vitro cytotoxic activity on ethanolic extracts of leaves of Ipomoea Pes-Tigridis (Convolulaceae) Against liver Hepg2 cell line. Int. J. Ayurv. Herbal Med. 5, 1778–1784. 10.18535/ijahm [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behere P. B., Das A., Yadav R., Behere A. P. (2013). Ayurvedic concepts related to psychotherapy. Indian J. Psychiatry 55, 310–314. 10.4103/0019-5545.105556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat B. A., Ahmad M., Amin T., Ahmad A., Shah W. A. (2015). Evaluation of phytochemical screening, anticancer and antimicrobial activities of Robinia pseudoacacia. Am. J. Pharmacy Health Res. 3, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bhoopat L., Srichairatanakool S., Kanjanapothi D., Taesotikul T., Thananchai H., Bhoopat T. (2011). Hepatoprotective effects of lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.): a combination of antioxidant and anti-apoptotic activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 136, 55–66. 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhouri W., Boubaker J., Skandrani I., Ghedira K., Ghedira L. C. (2012). Investigation of the apoptotic way induced by digallic acid in human lymphoblastoid TK6 cells. Cancer Cell Int. 12:26. 10.1186/1475-2867-12-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas J., Roy M., Mukherjee A. (2015). Anticancer drug development based on phytochemicals. J. Drug Disc. Develop. Delivery 2, 1012. [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Yi F. F., Bian Z. Y., Shen D. F., Yang L., Yan L., et al. (2009). Crocetin protects against cardiac hypertrophy by blocking MEK-ERK1/2 signaling pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13, 909–925. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00620.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carsuso M., Colombo A. L., Fedeli A. L., Pavesi A., Quaroni S., Saracchi M., et al. (2000). Isolation of endophytic fungi and actinomycetes taxane producers. Ann. Microbiol. 50, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chan L. L., George S., Ahmad I., Gonsangari S. L., Abbasi A., Cunningham B. T., et al. (2011). Cytotoxicity effects of Amoora rohituka and chittagonga on breast and pancreatic cancer cells. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011:860605. 10.1155/2011/860605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary S., Chandrashekar K. S., Pai K. S. R., Setty M. M., Devkar R. A., Reddy N. D., et al. (2015). Evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of extract and fractions of Nardostachys jatamansi DC in breast carcinoma. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 15, 1–13. 10.1186/s12906-015-0563-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checker R., Sharma D., Sandur S. K., Subrahmanyam G., Krishnan S., Poduval T. B., et al. (2010). Plumbagin inhibits proliferative and inflammatory responses of T cells independent of ROS generation but by modulating intracellular thiols. J. Cell. Biochem. 110, 1082–1093. 10.1002/jcb.22620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. Y., Hong W. J., Cho J. H., Kim E. M., Kim J., Jung C. H., et al. (2015). Podophyllotoxin acetate triggers anticancer effects against non-small cell lung cancer cells by promoting cell death via cell cycle arrest, ER stress and autophagy. Int. J. Oncol. 47, 1257–1265. 10.3892/ijo.2015.3123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csupor-Loffler B., Hajdu Z., Zupko I., Molnar J., Forgo P., Vasas A., et al. (2011). Antiproliferative Constituents of the Roots of Conyza Canadensis. Planta Med. 77, 1183–1188. 10.1055/s-0030-1270714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa L. S., Andreazza N. L., Correa W. R., Correa W. R., Cunha I. B. S., Ruiz A. L. T. G., et al. (2015). Antiproliferative activity, antioxidant capacity and chemical composition of extracts from the leaves and stem of Chresta sphaerocephala. Rev. Brasil. Farmacog. 25, 369–374. 10.1016/j.bjp.2015.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dasaroju S., Gottumukkala K. M. (2014). Current trends in research of Emblica officinalis (Amla): a pharmacological perspectives. Int. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. Rev. Res. 24, 150–159. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz L., Díaz-Muñoz M., García A. C., Méndez I. (2015). Mechanistic effects of calcitriol in cancer biology. Nutrients 7, 5020–5050. 10.3390/nu7065020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos K. P., Motta L. B., Santos D. Y. A. C., Salatino M. L. F., Salatino A., Ferreira M. J. P., et al. (2015). Antiproliferative activity of flavonoids from croton sphaerogynus Baill (Euphorbiaceae). Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 1–7. 10.1155/2015/212809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du G. J., Wang C. Z., Qi L. W., Zhang Z. Y., Calway T., He T. C., et al. (2013). The synergistic apoptotic interaction of panaxadiol and epigallocatechin gallate in human colorectal cancer cells. Phytother. Res. 27, 272–277. 10.1002/ptr.4707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einbonda L. S., Soffritti M., Esposti D. D., Park T., Cruz E., Su T., et al. (2009). Actein activates stress and statin associated responses and is bioavailable in Spague-Dawley rats. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 23, 311–321. 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00673.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hallouty S. M., Fayad W., Meky N. H., EL-Menshawi B. S., Wassel G. M., Hasabo A. A. (2015). In vitro anticancer activity of some Egyptian plant extracts against different human cancer cell lines. Int. J. Pharmtech Res. 8, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Elisa P., Elisa D., Fiorenza O., Guendalina L., Beatrice B., Paolo L., et al. (2015). Antiangiogenic and antitumor activities of berberine derivative NAX014 compound in a transgenic murine model of HER2/neu-positive mammary carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 36, 1169–1179. 10.1093/carcin/bgv103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elshamy H. A., Aboul-Soud M. A., Nassr-Allah A. A., Aboul-Enein K. M., Kabash A., Yagi A. (2010). Antitumor properties and modulation of antioxidant enzymes by Aloe vera leaf active principles isolated via supercritical carbon dioxide extraction. Curr. Med. Chem. 17, 129–138. 10.2174/092986710790112620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhoury I., Saad W., Bauhadir K., Nygren P., Stock R. S., Muhtasib H. G. (2016). Uptake, delivery and anticancer activity of thymoquinone nanoparticles in breast cancer cells. J. Nanopart. Res. 18, 210 10.1007/s11051-016-3517-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J., Shin H. R., Bray F., Forman D., Mathers C., Parkin D. M. (2010). Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int. J. Cancer 127, 2893–2917. 10.1002/ijc.25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamant L., Notte A., Ninane N., Raes M., Michiels C. (2010). Anti-apoptotic role of HIF-1 and AP-1 in paclitaxel exposed breast cancer cells under hypoxia. Mol. Cancer 9:191. 10.1186/1476-4598-9-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formagio A. S. N., Vieira M. C., Volobuff C. R. F., Silva M. S., Matos A. I., Cardoso C. A. L., et al. (2015). In vitro biological screening of the anticholinesterase and antiproliferative activities of medicinal plants belonging to Annonaceae. Brazil. J. Med. Biol. Res. 48, 308–315. 10.1590/1414-431X20144127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gach K., Dluqosz A., Janecka A. (2015). The role of anticancer activity of sesequiterpene lactones. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 388, 477–486. 10.1007/s00210-015-1096-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A. R., Peixoto I. T. A., Verde-Star M. J., Torre-Zavala D. L., Arnaut A., Ruiz A. L. T. Z. (2015). In vitro antimicrobial and antiproliferative activity of Amphipterygium adstringens. Evid Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 1–7. 10.1155/2015/175497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg P., Deep A. (2015). Anticancer potential of boswellic acid: a mini review. Hygeia J. Drugs Med. 7, 18–27. 10.15254/H.J.D.Med.7.2015.147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geethangili M., Rao Y. K., Fang S. H., Tzeng Y. M. (2008). Cytotoxic constituents from Andrographis paniculata induce cell cycle arrest in jurkat cells. Phytother. Res. 22, 1336–1341. 10.1002/ptr.2493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George B. P. A., Tynga I. M., Abrahamse H. (2015). In vitro antiproliferative effect of the acetone extract of Rubus fairholmianus gard root on human colorectal cancer cells. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 1–8. 10.1155/2015/165037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemzadeh A., Jaafar H. Z. E., Rahmat A. (2015). Optimization protocol for the extraction of 6-gingerol and 6-shogaol from Zingiber officinale var. rubrum and improving antioxidant and anticancer activity using response surface methodology. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 15:258. 10.1186/s12906-015-0718-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gospodinova Z., Krasteva M. (2015). Cichorium intybus L from Bulgaria inhibits viability of human breast cancer cells in vitro. Genet. Plant Physiol. 5, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Graidist P., Martla M., Sukpondma Y. (2015). Cytotoxic Activity of Piper cubeba extract in breast cancer cell lines. Nutrients 7, 2707–2718. 10.3390/nu7042707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm E. R., Moura M. B., Kelley E. E., van Houten B., Shiva S., Singh S. V. (2011). Withaferin A induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells is mediated by reactive oxygen species. PLoS ONE 6:e23354. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari M., Heidari-Vala H., Sadeghi M. R., Akhondi M. M. (2012). The inductive effects of Centella asiatica on rat spermatogenic cell apoptosis in vivo. J. Nat. Med. 66, 271–278. 10.1007/s11418-011-0578-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo B. G., Park Y. J., Park Y. S., Bae J. H., Cho J. Y., Park K., et al. (2014). Anticancer and antioxidant effects of extracts from different parts of indigo plant. Ind. Crops Prod. 56, 9–16. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.02.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K. L., Chung W. E., Choong K. E., Cheah Y. L., Phua E. Y., Srinivasan R. (2015). Anti-proliferative activity and preliminary phytochemical screening of Ipomoea quamoclit leaf extracts. Res. J. Med. Plant 9, 127–134. 10.3923/rjmp.2015.127.134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horn L., Pao W., Johnson D. H. (2012). Neoplasms of the lung, Chapter 89, in Harrisons Principles of Internal Medicine, 18th Edn., eds Longo D. L., Kasper D. L., Jamson J. L., Fauci A. S., Hauser S. L., Loscalzo J. (New York, NY: MacGraw-Hill; ). [Google Scholar]

- Hossan M. S., Rahman S., Bashar A. B. M. A., Jahan R., Al-Nahain A., Rahamatullah M. (2014). Rosmarinic acid: A review of its anticancer action. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 3, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hu M., Xu L., Yin L., Qi Y., Li H., Xu Y., et al. (2011). Cytotoxicity of dioscin in human gastric carcinoma cells through death receptor and mitochondrial pathways. J. Appl. Toxicol. 33, 712–722. 10.1002/jat.2715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R. Y., Chu Y. L., Jiang Z. B., Chen X. M., Zhang X., Zeng X. (2014). Glycyrrhyzin suppresses lung adenocarcinoma cell growth through inhibition of thromboxane synthase. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 33, 375–388. 10.1159/000356677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iweala E. E. J., Liu F. F., Cheng R. R., Li Y., Omonhinmin C. A., Zhang Y. J. (2015). Anticancer and free radical scavenging activity of some Nigerian food plants in vitro. Int. J. Cancer Res. 11, 41–51. 10.3923/ijcr.2015.41.51 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiju V. (2015). Evaluation of in vitro anticancer activity of hydroalcoholic extract of Justicia tranquibariensis. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Biosci. 2, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Lu Z., Cao K., Zhu Y., Chen Q., Zhu F., et al. (2010). The antitumor activity of homo-harringtonine against human mast cells harboring the KIT D816V mutation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 9, 211–223. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbashi A. S., Garbi M. I., Osman E. E. (2015). Antigiardial, antioxidant activities and cytotoxicity of ethanolic extract of leaves of Acacia nilotica. Adv. Med. Plant Res. 3, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kaladhar D. S. V. G. K., Saranya K. S., Vadlapudi V., Yarla N. S. (2014). Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative activity of Abutilon indicum L plant ethanolic leaf extract on lung cancer cell line A549 for system network studies. J. Cancer Sci. Ther. 6, 195–201. 10.4172/1948-5956.1000271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar S., Choudhury S. R., Banik N. L., Swapan R. K. (2011). Molecular mechanisms of anti-cancer action of garlic compounds in neuroblastoma. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 11, 398–407. 10.2174/187152011795677553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H., Anand M., Goyal D. (2011). Extraction of tylophorine from in-vitro raised Manju plants of Tylophora indica. J. Med. Plants Res. 5, 729–734. [Google Scholar]

- Keglevich P., Hazai L., Kalaus G., Szantay C. (2012). Modifications of basic skeleton of vinblastin and vincristine. Molecules 17, 5893–5914. 10.3390/molecules17055893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalafalla M. M., Abdellatef E., Dafalla H. M., Nassrallah A. A., Aboul-Enein K. M., Hany A., et al. (2011). Dedifferentiation of leaf explants and antileukemia activity of an ethanolic extract of cell cultures of Moringa oleifera. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10, 2746–2750. 10.5897/AJB10.2099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. Y., Lee S. G., Oh T. J., Lim S. R., Kim S. H., Lee H. J., et al. (2015). Antiproliferative and apoptotic activity of Chamaecyparis obtuse leaf extract against the HCT116 human colorectal cancer cell line and investigation of the bioactive compound by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Molecules 20, 18066–18082. 10.3390/molecules201018066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. J., Kim H. (2015). Anticancer effect of lycopene in gastric carcinogenesis. J. Cancer Prev. 20, 92–96. 10.15430/JCP.2015.20.2.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konariková K., Ježovicová M., Keresteš J., Gbelcová H., Duracková Z., Žitvanová I. (2015). Anticancer effect of black tea extract in human cancer cell lines. Springerplus 4, 1–6. 10.1186/s40064-015-0871-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M., MacKinnon S. L., Craft C. C., Matchett M. D., Hurta R. A., Neto C. C. (2011). Ursolic acid and its esters: occurrence in cranberries and other Vaccinium fruit and effects on matrix metalloproteinase activity in DU145 prostate tumor cells. J. Sci. Food Agric. 91, 789–796. 10.1002/jsfa.4330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppikar S. J., Choudhari A. S., Suryavanshi S. A., Kumari S., Chattopadhyay S., Kaul-Ghanekar R. (2010). Aqueous Cinnamon Extract (ACE-c) from the bark of Cinnamomum cassia causes apoptosis in human cervical cancer cell line (SiHa) through loss of mitochondrial membrane potential. BMC Cancer 10:210. 10.1186/1471-2407-10-210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Król S. K., Kiełbus M., Rivero-Müller A. R., Stepulak A. (2015). Comprehensive review on betulin as a potential anticancer agent. Biomed Res. Int. 2015:584189. 10.1155/2015/584189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Kashyap P. (2015). Antiproliferative activity and nitric oxide production of a methanolic extract of Fraxinus micrantha on Michigan cancer foundation-7 mammalian breast carcinoma cell line. J. Interc. Ethnopharmacol. 4, 109–113. 10.5455/jice.20150129102013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M. C., Chang S. J., Hsieh M. C. (2015). Colchicine significantly reduces incident cancer in Gout male patients. Medicine 94:e1570. 10.1097/MD.0000000000001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam S. K., Ng T. B. (2009). Novel galactonic acid-binding hexameric lectin from Hibiscus mutabilis seeds with antiproliferative and potent HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitory activities. Acta Biochim. Pol. 56, 649–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I. C., Choi B. Y. (2016). Withaferin A: a natural anticancer agent with pleiotropic mechanisms of action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:290. 10.3390/ijms17030290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Kim J. H. (2016). Kaempferol inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth and migration through the blockade of EGFR-related pathway in vitro. PLoS ONE 11:e0155264. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyva-Peralta M. A., Robles-Zepeda R. E., Garibay-Escobar A. G., Ruiz-Bustos E., Alvarez-Berber L. P., Galvez-Ruiz J. C. (2015). In vitro anti-proliferative activity of Argemone gracilenta and identification of some active components. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 15:13. 10.1186/s12906-015-0532-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. S., Li C. Y., Li Z. L., Zhu H. L. (2012). Genistein and its synthetic analogs as anticancer agents. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 12, 271–281. 10.2174/187152012800228788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Peng Z., Su C. (2015). Potential anticancer activities and mechanisms of costunolide and dehydrocostuslactone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 10888–10906. 10.3390/ijms160510888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z. Y., Kuo C. H., Wu D. C., Chuang W. L. (2016). Anticancer effects of acceptable colchicine concentrations on human gastric cancer cell lines. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 32, 68–73. 10.1016/j.kjms.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Q., Tian J., Qian K., Zhao X. B., Susan L. M., Yang L., et al. (2015). Recent progress on c-4 modified Podophyllotoxin analogs as potent antitumor agents. Med. Res. Rev. 35, 1–62. 10.1002/med.21319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Yadev V. R., Aggarwal B. B., Nair M. G. (2010). Inhibitory effects of black pepper (Piper nigrum) extracts and compounds on human tumor cell proliferation, cyclooxy genase enzymes, lipid peroxidation and nuclear transcription factor-kappa-B. Nat. Prod. Commun. 5, 1253–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long G., Wang G., Ye L., Lin B., Wei D., Liu L., et al. (2009). Important role of TNF-α in inhibitory effects of Radix sophorae flavescentis extract on vascular restenosis in a rat carotid model of balloon dilatation injury. Planta Med. 75, 1293–1299. 10.1055/s-0029-1185602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthra P. M., Lal N. (2016). Prospective of curcumin, a pleiotropic signaling molecule from Curcuma longa in the treatment of glioblastoma. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 109, 23–35. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneerat W., Thain S., Cheenpracha S., Prawat U., Laphookhieo S. (2011). New amides from the seeds of Clausana lansium. J. Med. Plants Res. 5, 2812–2815. [Google Scholar]

- Mbaveng A. T., Kuete V., Mapunya B. M., Beng V. P., Nkengfack A. E., Meyer J. J., et al. (2011). Evaluation of four Cameroonian medicinal plants for anticancer, antigonorrheal and antireverse transcriptase activities. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 32, 162–167. 10.1016/j.etap.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta F. C. M., Santos D. Y. A. C., Salatino M. L. F., Almeida J. M. D., Negri G., Carvalho J. E., et al. (2011). Constituents and antiproliferative activity of extracts from leaves of Croton macrobothrys. Rev. Brasil. Farmacogn. 21, 972–977. 10.1590/S0102-695X2011005000174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhija M., Singh M. P., Dhar K. L., Kalia A. N. (2015). Cytotoxic and antioxidant activity of Zanthozylum alatum stem bark and its flavonoid constituents. J. Pharmacog. Phytochem. 4, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Murawski N., Pfreundschuh M. (2010). New drugs for aggressive B-cell and T-cell lymphomas. Lancet Oncol. 11, 1074–1085. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70210-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair R. S., Snima K. S., Kamath R. C., Nair S. V., Lakshmanan V. K. (2015). Synthesis and characterization of Careya arborea nanoparticles for assessing its in vitro efficacy in pancreatic cancer cells. J. Nat. Prod. 8, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunwande I. A., Walker T. M., Bansal A., Setzer W. N., Essien E. E. (2010). Essential oil constituents and biological activities of Peristrophe bicalyculata and Borreria verticillata. Nat. Prod. Commun. 5, 1815–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahari P., Saikia U. P., Das T. P., Damodaran C., Rohr J. (2016). Synthesis of psoralidin derivatives and their anticancer activity: first synthesis of lespeflorin l1. Tetrahedron 72, 3324–3334. 10.1016/j.tet.2016.04.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S., Chakraborty S., Mukherjee A., Kundu R. (2015). Evaluation of cytotoxicity and DNA damaging activity of three plant extracts on cervical cancer cell lines. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 31, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Perrone D., Ardito F., Giannatempo G., Dioguardi M., Troiano G., Russo L. L., et al. (2015). Biological and therapeutic activities and anticancer properties of curcumin. Exp. Ther. Med. 10, 1615–1623. 10.3892/etm.2015.2749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan D., Tripathy G. (2014). Antiproliferative activity of Trapa acornis shell extracts against human breast cancer cell lines. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 5, 2238–2243. [Google Scholar]

- Preethi R., Padma P. R. (2016). Anticancer activity of silver nanobioconjugates synthesized from Piper betle leaves extract and its active compound eugenol. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 8, 201–205. 10.22159/ijpps.2016.v8i9.12993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Priya V., Srinivasa R. A. (2015). Evaluation of anticancer activity of Tridax procumbens leaf extracts on A549 and HepG2 cell lines. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 8, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan E. K., Bava S. V., Narayanan S. S., Nath L. R., Thulasidasan A. K. T., Soniya E. V., et al. (2014). 6-Gingerol induces caspase dependent apoptosis and prevents PMA- induced proliferation in colon cancer cells by inhibiting MAPK/AP-1 signaling. PLoS ONE 9:e104401. 10.1371/journal.pone.0104401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafshanjani M. A. S., Parvin S., Kader M. A., Sharmin T. (2015). Preliminary phytochemical screening and cytotoxic potentials from leaves of Sanchezia speciosa Hook f. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 1, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Raihan M. O., Tareq S. M., Brishti A., Alam M. K., Haque A., Ali M. S. (2012). Evaluation of antitumor activity of Leea indica (Burm.f.) merr extract against Ehrlich ascites carcinoma (EAC) bearing mice. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. 4, 143–152. 10.5099/aj120200143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjani R., Ayya R. M. (2012). Anticancer properties of Allium sativum- a review. Asian J. Biochem. Pharm. Res. 3, 190–196. [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi N., Duggal S., Singh S. K., Porwal K., Srivastava V. K., Maurya R., et al. (2015). Proteosome inhibition mediates p53 reactivation and anticancer activity of 6-gingerol in cervical cancer cells. Oncotarget 6, 43310–43325. 10.18632/oncotarget.6383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnekenburger M., Dicato M., Diederich M. (2014). Plant derived epigenetic modulators for cancer treatment and prevention. Biotechnol. Adv. 32, 1123–1132. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvarani S., Moorthi P. V., Saranya P., Abirami M. (2015). Anti-cancer activity of silver nanoparticle synthesized from stem extract of Ocimum Kilimandscharicum against Hep-G2, liver cancer cell line. Kenkyu J. Nanotechnol. Nanosci. 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A., Ozbas S. T., Akbuga J., Bitis L. (2015). In vitro antiproliferative activity of Endemic Centaurea kilaea Boiss against human tumor cell lines. Musbed 5, 149–153. 10.5455/musbed.20150602022750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo H. S., Jo J. K., Ku J. M., Choi H. S., Choi Y. K., et al. (2015). Induction of caspase dependent extrinsic apoptosis through inhibition of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling in HER2-overexpressing BT-474 breast cancer cells. Biosci. Rep. 35:e00276. 10.1042/BSR20150165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra D., Paixao J., Nunes C., Dinis T. C. P., Almeida L. M. (2013). Cyanidine-3-Glucoside suppresses cytokine induced inflammatory response in human intestinal cells: Comparison with 5-aminosalicylic acid. PLoS ONE 8:e73001. 10.1371/journal.pone.0073001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S., Ramakrishnan M., Thylur R. P., Shivanna Y. (2015). In-vitro evaluation of anti proliferative and haemolysis activity of selected plant extracts on lung carcinoma (A549). Int. J. Plant Sci. Ecol. 1, 208–212. [Google Scholar]

- Shakeera B. M., Sujatha K. (2015). In-vitro cytotoxicity studies of Psidium guajava against Ehrlich ascites carcinoma cell lines. Indian J. Sci. 15, 218–231. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma B., Singh S., Kanwar S. S. (2014). L-Methionase: a therapeutic enzyme to treat malignancies. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 1–13. 10.1155/2014/506287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D. Y., Kim G. Y., Li W., Choi B. T., Kim N. D., Kang H. S., et al. (2009). Implication of intracellular ROS formation, caspase-3 activation and Egr-1 induction in platycodon D-induced apoptosis of U937 human leukemia cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 63, 86–94. 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Jemal A. (2016). Cancer statistics 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 7–30. 10.3322/caac.21332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B. N., Shankar S., Srivastava R. K. (2011). Green tea catechin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG): mechanisms, perspectives and clinical applications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 82, 1807–1821. 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.07.093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Gupta J., Kanwar S. S. (2014). Antilipase, antiproliferatic and antiradical activities of methanolic extracts of Vinca major. J. Pharm. Phytochem. 3, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Jarial R., Kanwar S. S. (2013). Therapeutic effect of herbal medicines on obesity: herbal pancreatic lipase inhibitors. Wudpecker J. Med. Plants 2, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sneha S., Sharath R., Aishwarya K. S., Samrat K., Vasundhara M., Radhika B., et al. (2015). Screening of the anti-oxidant, antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of the methanolic extracts of Elaeocarpus ganitrus and Elaeocarpus serratus. Int. Res. J. Innov. Eng. 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman G. M. (2016). Molecular structure and antiproliferative effect of galangin in HCT116 cells: In vitro study. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 25, 247–252. 10.1007/s10068-016-0036-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester P. W., Ayoub N. M. (2013). Tocotrienols target PI3K/Akt signaling in anti-breast cancer therapy. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 13, 1039–1047. 10.2174/18715206113139990116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai J., Cheung S., Wu M., Hasman D. (2012). Antiproliferation effect of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) on human ovarian cancer cells in vitro. Phytomedicine 19, 436–443. 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantengco O. A. G., Jacinto S. D. (2015). Cytotoxic activity of crude extracts and fractions from Premna odorata (Blanco), Artocarpus camansi (Blanco) and Gliricidia sepium (Jacq) against selected human cancer cell lines. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 5, 1037–1041. 10.1016/j.apjtb.2015.09.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V. S., Deb G., Babcook M. A., Gupta S. (2014). Plant phytochemicals as epigenetic modulators: role in cancer chemoprevention. AAPS J. 16, 151–163. 10.1208/s12248-013-9548-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangapazham R. L., Sharad S., Maheshwari R. K. (2016). Phytochemicals in wound healing. Adv. Wound Care 5, 230–241. 10.1089/wound.2013.0505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu L. Y., Pi J., Jin H., Cai J. Y., Deng S. P. (2016). Synthesis, characterization and anticancer activity of kaempferol-zinc(II) complex. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. Lett. 26, 2730–2734. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.03.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umadevi M., Kumar K. P. S., Bhowmik D., Duraivel S. (2013). Traditionally used anticancer herbs in india. J. Med. Plants Stud. 1, 56–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vallianou N. G., Evangelopoulos A., Schizas N., Kazazis C. (2015). Potential anticancer properties and mechanisms of action of curcumin. Anticancer Res. 35, 645–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Meter M. E., Kim E. S., Bevacizumab (2010). Current updates in treatment. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 22, 586–591. 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833edc0c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoni E. M., Lo Faro A. F., Shnti-Rad J., Inti M. (2016). Anticancer molecular mechanisms of resveratrol. Front. Nutrit. 3:8. 10.3389/fnut.2016.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahyu W., Laura W., Teresa L. W., Indra B., Yellianty Y., Dian R. L. (2013). Antioxidant, anticancer and apoptosis-inducing effects of Piper extracts in HeLa cells. J. Exp. Integr. Med. 3, 225–230. 10.5455/jeim.160513.or.074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wal A., Srivastava R. S., Wal P., Rai A., Sharma S. (2015). Lupeol as a magic drug. Pharm. Biol. Eval. 2, 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Phan D. D., Zhang J., Ong P. S., Thuya W. L., Soo R. A., et al. (2016). Anticancer properties of nimbolide and pharmacokinetic considerations to accelerate its development. Oncotarget. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.18632/oncotarget.8316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Xu G. F., Liu X. X., Chang A. X., Xu M. L., Ghimeray A. K., et al. (2012). In vitro antioxidant properties and induced G2/M arrest in HT-29 cells of dichloromethane fraction from Liriodendron tulipifera. J. Med. Plants Res. 6, 424–432. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Hong C., Qu H. (2011). Screening of antitumor compounds psoralen and isopsoralen from Psoralea corylifolia L seeds. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011, 363052. 10.1093/ecam/nen087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver B. A. (2014). How taxol/ paclitaxel kills cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 2677–2681. 10.1091/mbc.E14-04-0916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen L., Wu D., Jiang Y., Prasad K. N., Lin S., Jiang G., et al. (2014). Identification of flavonoids in litchi (Litchi chinensis) leaf and evaluation of anticancer activities. J. Funct. Foods 6, 555–563. 10.1016/j.jff.2013.11.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak L., Skapska S., Marszalek K. (2015). Ursolic acid- a pentacyclic triterpenoid with a wide spectrum of pharmacological activities. Molecules 20, 20614–20641. 10.3390/molecules201119721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong M., Wang L., Yu H. L., Han H., Mao D., Chen J., et al. (2016). Ginkgetin exerts growth inhibitory and apoptotic effects on osteosarcoma cells through inhibition of STAT3 and activation of caspase-3/9. Oncol. Rep. 35, 1034–1040. 10.3892/or.2015.4427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Bower K. A., Wang S., Frank J. A., Chen G., Ding M., et al. (2010). Cyanidin-3-Glucoside inhibits ethanol induced invasion of breast cancer cells overexpressing ErbB2. Mol. Cancer 9:285. 10.1186/1476-4598-9-285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav B., Bajaj A., Saxena A. K. (2010). In vitro anticancer activity of the root, stem and leaves of Withania somnifera against various human cancer cell lines. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 72, 659–663. 10.4103/0250-474X.78543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M., Kaneko M., Tokuda H., Nishimura K., Kumeda Y., Iida A. (2009). Synthesis and evaluation of bioactive naphthoquinones from the Brazilian medicinal plant, Tabebuia avellanedae. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 17, 6286–6291. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C. H., Li F., Ma Y. C. (2015). Plumbagin shows anticancer activity in human osteosarcoma (MG-63) via the inhibition of s-phase checkpoints and downregulation of c-myc. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 14432–14439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Heo S., Wang M. H. (2008). Antioxidant and anticancer activities of methanol and water extracts from leaves of Cirsium japonicum. J. Appl. Biol. Chem. 51, 160–164. 10.3839/jabc.2008.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yumrutas O., Oztuzcu S., Pehlivan M., Ozturk N., Eroz Poyraz I., Ziya Iğci Y., et al. (2015). Cell viability, anti-proliferation and antioxidant activities of Sideritis syriaca, Tanacetum argenteum subsp argenteum and Achillea aleppica subsp zederbaueri on human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7). J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 5, 1–5. 10.7324/JAPS.2015.50301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y., Jia G., Wu D., Xu Y., Xu L. (2009). Design and synthesis of a gossypol derivative with improved antitumor activities. Arch. Pharm. Chem. Life Sci. 342, 223–229. 10.1002/ardp.200800185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Y., Huang C. T., Liu S. M., Wang B., Guo J., Bai J. Q., et al. (2016). Licochalcone A exerts antitumor activity in bladder cancer cell lines and mouse models. Tropic. J. Pharm. Res. 15, 1151–1157. 10.4314/tjpr.v15i6.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Li S., Lian X. Y. (2010). An overview of genus aesculus L ethnobotany, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activities. Pharma Crops 1, 24–51. 10.2174/2210290601001010024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Gao W., Li K. (2008). Chinese herbal medicines in the treatment of lung cancer. Asian J. Tradit. Med. 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zilla M. K., Nayak D., Amin H., Nalli Y., Rah B., Chakraborty S., et al. (2014). 4'-Demethyl-deoxypodophyllotoxin glucoside isolated from Podophyllum hexandrum exhibits potential anticancer activities by altering Chk-2 signaling pathway in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 224, 100–107. 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]