Abstract

Background

Establishing a presurgical baseline of neurocognitive functioning for pediatric brain tumor patients is a high priority to identify level of functioning prior to medical interventions. However, few studies have obtained adequate samples of presurgery assessments.

Methods

This study examines the feasibility of completing tests to assess pre-surgical neurocognitive functioning in 59 identified pediatric brain tumor patients.

Results

Eighty-five percent of patients (n = 50) were referred by the neurosurgery team before surgery and 83% of patients (n = 49) enrolled in the study. A full battery, including both performance-based and parent-report measures of neurocognitive function, was completed for 54% (n = 32) of patients. Rates of completion for either parent-report or performance-based measures were 68% (n = 40) and 69% (n = 41), respectively. While the performance-based assessment fell within the average range (M = 95.4, SD = 14.7, 95% CI, 90.7–100.0), 32% of participants had scores one or more standard deviations below the mean, or twice the expected rate. Parent-reports indicated higher level of concern than the general population (M = 55.4, SD = 11.3, 95% CI, 51.8–59.0) and found that 35% fell one or more standard deviations above the mean, or more than twice the expected rate.

Conclusions

Results suggest it is feasible to conduct pre-surgical assessments with a portion of pediatric brain tumor patients upon diagnosis and these results compare favorably with prior research. However, nearly half of identified patients did not receive a full test battery. Identifying barriers to enrollment and participation in research are discussed as well as recommendations for future research.

Keywords: neurocognitive function, pediatric brain tumors, presurgical assessment

As a group, brain tumors are the most common solid tumor diagnosis of childhood, and malignant brain tumors are the second most common cancer diagnosis in patients under age 20.1,2 The incidence rate is approximately 4.8 cases per 100 000 children annually and it is estimated that 4200 new cases of childhood primary nonmalignant and malignant central nervous system (CNS) tumors were diagnosed in the United States in 2011.3 Due to treatment advances, the survival rates for children with brain tumors have risen dramatically with the overall 5-year survival rate following diagnosis of a primary malignant tumor for children under age 20 reaching 72.6% by 2008.3 However, due to the aggressive nature of treatment, the increased survival rate has been accompanied by high levels of adverse late effects in multiple domains including chronic health problems, neurocognitive deficits, and psychosocial late effects.4–6 The National Cancer Institute Brain Tumor Progress Review Group Report has recommended that routine cognitive and quality-of-life assessment become the standard of care for brain tumor patients.7

Significant deficits in neurocognitive function in survivors of childhood brain tumors are well documented and are one of the most prominent negative consequences. A recent meta-analysis of 39 studies published between 1992 and 2009 found large effects compared to test norms for measures of intelligence.8 However, previous research has focused primarily on late effects, with children in these studies being assessed on average 5 years postdiagnosis and 4 years posttreatment, and the vast majority of studies were cross-sectional with cognitive function assessed at only one time point.8 Building on these studies, it will be important for future research on neurocognitive function in children with brain tumors to include assessment of cognitive function prior to surgery or adjuvant treatment.

Obtaining data on children's cognitive function prior to surgery is important for several reasons. Prospective, longitudinal designs that track children beginning at diagnosis (ie, presurgery) through posttreatment follow-ups are essential to disentangle which factors (eg, tumor type, location, and severity as well as type of treatment including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy) may account for negative outcomes. Meyers and Brown highlight the importance of establishing neurocognitive end points in order to understand what cognitive problems exist pretreatment to establish a baseline.9 Assessment of cognitive function presurgery is likely affected by a range of factors (eg, conducting assessments in the hospital and patients' levels of emotional distress, fatigue, vomiting, dizziness, complications such seizures or hydrocephalus). These factors notwithstanding, presurgical assessment provides a significantly better opportunity to measure baseline functioning compared with attempting to establish a baseline during or after treatment has commenced. Moreover, because it is rare for patients to have completed a cognitive assessment prior to diagnosis, presurgical assessment offers the only opportunity to measure cognitive function prior to surgery and adjuvant therapy. This benchmark would provide a point of comparison for later test results that would be helpful for caregivers, providers, and educators to interpret how functioning has changed (or remained stable) over the course of treatment and recovery.

Relatively few studies of pediatric brain tumor patients have obtained an adequate sample of pre-surgical assessment (ie, less than 10% of patients were tested prior to surgery or the onset of adjuvant therapy).10–13 For example, Stargatt et al13 were able to complete presurgery cognitive testing on only 6 of 34 children. They describe a number of challenges to testing prior to surgery, including premorbid characteristics of the children, acute effects of the tumor, and psychological stress.13 An additional challenge is the time constraint of conducting an assessment during the short window, typically 1 or 2 days, between diagnosis and surgery. Therefore, although a comprehensive assessment would be ideal, it is important to employ brief test batteries in order to accommodate this constraint and to minimize effects due to patient fatigue.14

The present study was designed to examine the feasibility of enrolling and measuring cognitive function, using age-appropriate measures, in a sample of pediatric brain tumor patients prior to their undergoing surgery. First, to address feasibility we report on rates of accrual into the study, completion of performance-based neurocognitive function, and parent-reported assessment of patients' neurocognitive function prior to surgery. Second, we present initial findings on the neurocognitive function of these patients to establish presurgery levels of cognitive function.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Eligible participants in the current study included 59 patients who were identified over 2 years through the Department of Pediatric Neurosurgery at a university-based children's hospital as having a primary brain tumor for which surgical resection was needed. Of the 59 patients who were consecutively admitted, 50 (85%) of these patients were referred to the study prior to the patient's surgery. Forty-nine (83%) of their parents provided consent and they were enrolled in the study examining presurgical neurocognitive functioning, approved by the University's Institutional Review Board. Individual demographic data as well as medical diagnostic information (tumor type, World Health Organization [WHO] grade, supratentorial versus infratentorial tumor location, and presence of hydrocephalus) are presented in Table 1. See Table 2 for a summary of sample demographics and tumor characteristics.

Table 1.

Individual participant demographic, medical, and neurocognitive data

| ID | Sex | Age | Tumor Type | WHO grade | Location | Hydrocephalus | FSIQa | GECb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 13.3 | Ependymoma | high | infra | yes | 96 | 40 |

| 2 | Male | 10.8 | Germinoma | high | supra | no | 85 | 70 |

| 3 | Male | 2.3 | Cortical Dysplasia | low | supra | no | 95 | 60 |

| 4 | Male | 10.2 | Glioma | low | supra | no | 93 | 68 |

| 5 | Male | 4.9 | Medulloblastoma | high | infra | no | 103 | 36 |

| 6 | Male | 7.8 | Glioblastoma | high | supra | yes | 46 | |

| 7 | Female | 7.3 | Glioma | high | supra | no | 81 | 48 |

| 8 | Male | 8.1 | Medulloblastoma | high | infra | yes | 118 | 61 |

| 9 | Female | 11.8 | Glioma | low | supra | no | 96 | 59 |

| 10 | Male | 14.1 | Glioma | low | supra | yes | 105 | 40 |

| 11 | Female | 11.8 | Glioma | high | infra | yes | 108 | |

| 12 | Female | 4.4 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | yes | 112 | 48 |

| 13 | Male | 16.8 | Astrocytoma | low | supra | no | 103 | 54 |

| 14 | Male | 2.6 | Glioma | low | supra | yes | 76 | |

| 15 | Male | 11.3 | Germinoma | high | supra | yes | 92 | 67 |

| 16 | Female | 3 | Ependymoma | high | infra | yes | 76 | 73 |

| 17 | Male | 2.8 | Hamartoma | low | infra | no | 70 | |

| 18 | Male | 5.4 | Medulloblastoma | high | infra | yes | 83 | 55 |

| 19 | Female | 7.8 | DNT | low | supra | no | 125 | 66 |

| 20 | Female | 2 | Astrocytoma | low | supra | no | 90 | |

| 21 | Male | 14.2 | Medulloblastoma | high | infra | no | 76 | 57 |

| 22 | Male | 0.4 | Choroid plexus papilloma | low | supra | yes | 85 | |

| 23 | Male | 2.9 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | yes | 76 | 68 |

| 24 | Male | 10.5 | Medulloblastoma | high | infra | yes | 77 | 37 |

| 25 | Male | 9.3 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | no | 113 | |

| 26 | Female | 6.2 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | yes | 122 | 33 |

| 27 | Male | 12.4 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | no | 120 | |

| 28 | Male | 7.6 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | yes | 85 | 42 |

| 29 | Female | 5.5 | Glioblastoma | high | infra | no | 91 | |

| 30 | Female | 6.8 | Choroid plexus papilloma | low | infra | no | 127 | 59 |

| 31 | Female | 9.3 | Craniopharyngioma | low | supra | no | 99 | 43 |

| 32 | Male | 14.2 | Ganglioglioma | low | supra | no | 91 | 71 |

| 33 | Female | 11.6 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | yes | 96 | 67 |

| 34 | Male | 16.9 | PNET | high | supra | no | 90 | 55 |

| 35 | Male | 15.3 | Glioma | low | supra | no | 44 | |

| 36 | Female | 10.6 | Ganglioglioma | low | infra | no | 92 | 54 |

| 37 | Male | 17.8 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | no | 81 | 58 |

| 38 | Female | 2.2 | PNET | high | supra | no | 95 | 55 |

| 39 | Female | 2.6 | Medulloblastoma | high | infra | yes | 85 | 56 |

| 40 | Female | 12.6 | Glioblastoma | high | supra | no | 86 | 41 |

| 41 | Male | 5.8 | Medulloblastoma | high | infra | yes | 63 | |

| 42 | Female | 2.9 | Teratoid/rhaboid | high | infra | yes | 103 | |

| 43 | Male | 2.3 | Choroid plexus papilloma | low | supra | yes | 52 | |

| 44 | Male | 16.5 | Glioma | high | supra | no | 48 | |

| 45 | Male | 14.2 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | no | 59 | |

| 46 | Female | 5.8 | Glioma | low | supra | no | 52 | |

| 47 | Female | 4.3 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | yes | 112 | |

| 48 | Male | 5.8 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | yes | 77 | 70 |

| 49 | Male | 7.3 | Astrocytoma | low | infra | yes | 101 | 64 |

aFull Scale Intelligence Quotient.

bGeneral Executive Composite.

Supra, supratentorial; infra, infratentorial; PNET, primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

Table 2.

Summary of patient demographics, tumor characteristics, and neurocognitive functioning

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Males | 29 | 59 |

| Females | 20 | 41 |

| Age, M (SD) | 7.92 | (4.78) |

| Tumor type | ||

| Astrocytoma | 14 | 29 |

| Glioma | 9 | 18 |

| Medulloblastoma | 7 | 14 |

| Other | 19 | 39 |

| WHOa grade | ||

| Low | 29 | 59 |

| High | 20 | 41 |

| Tumor location | ||

| Supratentorial | 22 | 45 |

| Infratentorial | 27 | 55 |

| Hydrocephalus | ||

| Yes | 23 | 47 |

| No | 26 | 53 |

| Neurocognitive Testing, M (SD) | ||

| FSIQb | 95.4 | (14.7) |

| GECc | 55.4 | (11.3) |

aWorld Health Organization.

bFull Scale IQ.

cGeneral Executive Composite.

Measures

Demographics and medical chart review

Demographic information including the child's age and sex was provided by parents. Patients' charts were reviewed to collect information regarding tumor type, as well as dichotomous information regarding WHO grade (low vs high), location (supratentorial vs infratentorial), and presence or absence of hydrocephalus.

Performance-based assessment of neurocognitive function

One verbal and 1 performance IQ (VIQ and PIQ) subtest was administered from age-appropriate Wechsler Intelligence tests in order to estimate an age-standardized Full Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ) with a normative mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15. For participants ages 2 years, 6 months to 5 years, 11 months, the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scales of Intelligence – Third Edition (WPPSI-III)15 was used and for participants 6 years and older, the Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence (WASI)16 was administered. The association between individual subtests and their overall broader indices are highly correlated (r = 0.87–0.93).16 For participants under 2 years, 6 months of age, the cognitive domain of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development – Third Edition (BSID-III)17 was administered and also yielded an FSIQ score with a normative mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Scores between 90 and 110 are considered average.

Parent-report of neurocognitive function

Difficulties in neurocognitive function were assessed by the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF),18 a parent-report measure of children's day-to-day difficulties with tasks requiring working memory, initiation, planning/organizing, and emotional control. Scores yielded a broad General Executive Composite (GEC). The BRIEF-preschool version (BRIEF-P)19 was used for participants ages 2 through 4 years old and the standard BRIEF was used for participants 5 years and older. The GEC scores of the BRIEF and the BRIEF-preschool versions are presented as T-scores, which have a normative mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 (higher scores reflect greater problems in neurocognitive function). Scores below 65 are considered to be in the age-expected range. The BRIEF provides an index of parents' concerns about their children's problems in executive function.20

Procedure

The pediatric neurosurgery team identified newly diagnosed brain tumor patients and provided contact information to the psychology research team. A member of the research team then contacted the parents of identified patients to review the study in detail and determine their desire to participate. Parents provided informed consent and children over the age of 6 years provided assent. The test battery included direct performance-based assessment of neurocognitive function as well as parent-report of their children's functioning. As described above, specific subtests were administered dependent upon participant age.

The collaboration took significant commitment from the neurosurgery service since they initiated contact. The psychology team was available virtually around the clock and took a shift-coverage approach to each week. Shifts were divided between morning, afternoon, and weekends; coverage was achieved through a combination of portions of time dedicated by 2 masters-level research assistants and additional time from doctoral students in psychology. After an email was sent from neurosurgery to the psychology team about a newly diagnosed brain tumor requiring surgical intervention, a call was directed to the researcher or research assistant on-call via the project coordinator.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics are reported for the number and percentage of patients who were eligible, consented, enrolled, and tested. The data were analyzed for outliers and tests of skewness and kurtosis (ie, peakedness of the data relative to a normal distribution) yielded results all within acceptable ranges. Scores on the neurocognitive tests are reported, comparisons with the normative means for the respective tests are presented in a series of 2-tailed t-tests, and effect sizes (Cohen's d) are reported for the difference between the sample means and the test norms. Comparisons were made to normative means in order to establish how patients in this sample were functioning relative to same-age peers. We further examined rates of patients who were one or more standard deviations below the normative mean. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS version 23) and results were determined to be significant at P < .05.

Results

Feasibility of Recruitment, Enrollment, and Completion of Testing Presurgery

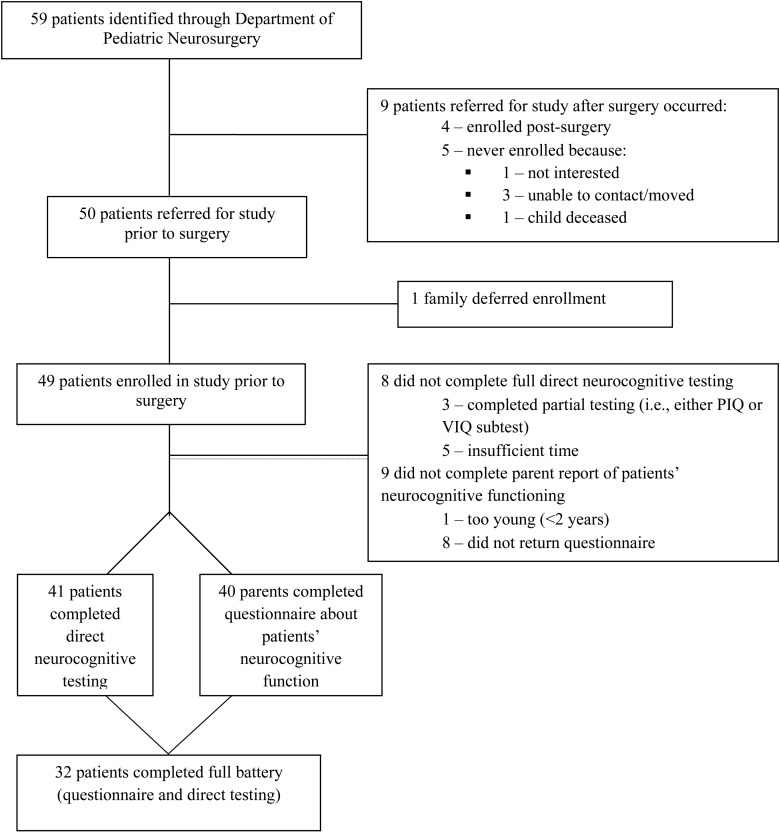

The recruitment, consenting, enrollment, and testing of pediatric brain tumor patients and their parents involved a series of steps (see Figure 1 for a summary of this process and for the rates of enrollment and testing).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of patients through the study from admission to neurocognitive testing.

Of the 59 patients identified over a 2-year period, 85% (n = 50) were successfully referred by the neurosurgery team to the psychology team for enrollment in the study prior to the patients' surgery. The remaining 9 patients were referred following surgery and 4 of those patients were successfully enrolled postsurgery. Five of the 9 patients who were referred to the psychology team after their surgery did not enroll due to lack of interest (n = 1), inability to be contacted/moved (n = 3), and death prior to being enrolled in the study (n = 1).

Eighty-three percent of identified patients (n = 49) provided consent to participate and were successfully enrolled in the study. One patient and his family asked to defer their enrollment due to being too overwhelmed at the time of the child's surgery, but were later enrolled at follow-up.

The age-appropriate neurocognitive test was successfully administered to 41 patients, which represents 69% of identified patients. It is noteworthy that an additional 3 patients (n = 44) completed part of the direct testing (either the verbal or performance subtest). The parent-based measure was completed for 68% of patients (n = 40). Of the 9 patients for whom we did not receive this measure, 1 was too young and the remaining 8 did not return the form. Complete data on both direct testing and parent reports were obtained for 54% of the eligible sample (n = 32).

Location and duration of presurgery testing

The majority of the direct neurocognitive testing (75%) took place in the patients' rooms on the inpatient unit of the hospital. The remaining testing took place in an outpatient clinic setting (25%). On average, the consenting and testing took approximately 40 minutes (M = 39.6; SD = 18.7).

Neurocognitive functioning

Results of the direct neurocognitive testing administered to 41 patients are presented in Table 1 and summary data are presented in Table 2. The mean FSIQ of the sample falls in the average range (M = 95.4; SD = 14.7; 95% CI, 90.7-100.0) and comparison to the normative mean was not significant (t = 3.01, P > .05; d = 0.31). We examined the percentage of children one or more standard deviations below the mean (ie, FSIQ ≤ 85) and found that 13 patients (32%) fell below this cut off.

Results of parent-reported neurocognitive functioning on the GEC scale of the BRIEF were compiled for 40 patients and are also presented in Table 1. The index mean on the GEC yielded a T-score that is one-half standard deviation above the normative mean (M = 55.4; SD = 11.3; 95% CI: 51.8-59.0) and represented a significant difference (t = 3.01, P = .005) and yielded a medium effect size (d = 0.51), indicating higher level of parent concern about their child's neurocognitive function in the current sample compared with the normative sample. We examined the percentage of children 1 or more standard deviations above the mean (ie, GEC ≥ 60) and found that 14 patients (35%) fell above this cut off. Consistent with findings from previous research,21 the correlation between IQ and BRIEF scores was not significant (r = −0.18, P = .31).

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to examine the feasibility of conducting a brief, pretreatment assessment with pediatric brain tumor patients. Eighty-five percent of patients were successfully referred to the psychology team for the study prior to the patients' surgery and the battery of testing was completed with 54% of eligible patients. The referral and enrollment rate of 85% suggests that it is feasible for a psychology research team to work effectively with the neurosurgery team for recruitment and successful enrollment of families prior to surgery in order to establish a pretreatment baseline. This percentage compares favorably with previous rates of recruitment for presurgical cognitive testing in this population. However, 9 of the 59 (15%) identified patients were not referred for the study prior to surgery. Given the heavy time demands on medical treatment providers and the short time window between diagnosis and surgery, it is imperative to have a clear system for referrals, close collaboration, and regular communication between the medical and research teams. Some specific strategies that contributed to our successful enrollment of presurgical patients included strong interest in the study from the neurosurgery service team and around-the-clock availability of the psychological team administering the assessments. The surgical team initiated contact with patients and their families and then provided the referral to the psychology team, who took a shift coverage approach to each week to ensure availability to enroll and test patients. While the psychology team was available for coverage 10 shifts per week plus weekend call, on average, less than 1 shift was filled per week. The study took place in an academic medical center and had the advantage of having close physical proximity between the hospital where children received treatment and the psychology team's lab. The medical team was composed of one pediatric neurosurgeon with one primary nurse. The psychology team was comprised of researchers and research assistants. In order to improve enrollment rates in future studies, it would be helpful for the psychology team to be able to directly monitor and identify newly admitted patients to ease some of the burden for the neurosurgery service.

Of the patients referred to the study prior to surgery, consent to participate was obtained for 98% (ie, all but one patient). This suggests that families are highly motivated to participate in research studies despite the major stress of a child being diagnosed with a brain tumor. Anecdotally, families reported a strong desire to do everything they could to help other families who may be dealing with a brain tumor diagnosis in the future, as well as to receive feedback about their child's cognitive functioning that was provided as part of their participation. Overall, these data provide strong support for the feasibility of enrolling patients and their families to participate in a brief, neurocognitive assessment prior to undergoing surgery.

However, as reflected in the 54% completion rate for the neurocognitive battery, it is important to note several impediments that made conducting direct assessment and gathering questionnaire data a challenge under these circumstances. One such impediment was working around the multiple demands and scheduled procedures that families faced prior to children's surgery (eg, presurgical scans, visits from health care personnel, family visitation). Additionally, the typical window from time of referral from the medical team to complete testing was approximately 24 to 48 hours. Given this tight window it was not possible to conduct testing in all cases. Insufficient time between referral and surgery was an issue for 4 of the children enrolled. Further, 8 of the parents in the sample did not complete the BRIEF and demographic questionnaire. Parents often appeared overwhelmed and if they did not complete the measures during their hospital stay, the measures most often were not returned. Therefore, future studies should emphasize the need for parents to complete measures prior to or during the child's hospital stay as well as to coordinate efforts for questionnaire completion with nursing staff. Importantly, although one may suspect that the children would be too distressed to complete testing, level of distress only prevented testing for 1 child in our sample.

The second primary aim of this study was to present initial findings from our brief neurocognitive test battery. The results of intellectual functioning were below the population mean but within the average range. However, approximately one third of patients fell one or more standard deviations below the normative mean, which is approximately twice what is expected in the normal distribution. Similarly, with regard to parents' reports of their children's neurocognitive functioning, scores also fell in the age-expected range; however, the sample mean scores indicated significant impairment relative to the normative mean with a half of a standard deviation elevation for the BRIEF GEC ratings. Moreover, over one-third of patients' parent-reported GEC T-scores fell 1 or more standard deviations above the normative mean, which is more than double the expected rate. Given the relatively increased rates of difficulty in a subgroup of this sample as measured by both direct assessment and parent report, these baseline markers of functioning are critical to understand and correctly attribute disease and treatment factors that may or may not be related to trajectories of functioning over time. However, it is also noteworthy that both parent-report and performance-based scores indicate that children in this study of pretreatment functioning were faring better relative to the large effect sizes noted in a recent meta-analysis of pediatric brain tumor survivors.8 Therefore, future research is needed to examine functioning over time to understand who is at greatest risk, when and if declines take place, as well as what factors, such as treatment type or tumor type and location, may contribute to declining function.

Despite its strengths, the present study has several limitations. The sample is highly variable with regard to age and tumor type, which makes it difficult to interpret how these factors relate to functioning. It is also noteworthy that as found in other studies,21 performance-based measures of intellectual functioning were not related to parent-report measures of this construct. Further research is needed to continue to understand the meaning of these 2 indices of children's cognitive function. Furthermore, the small size of the current sample prevented group comparisons of neurocognitive functioning by demographic factors (eg, gender) or tumor characteristics (eg, tumor grade, location). It is also unclear whether some factors, such as presence of a space-occupying lesion, hydrocephalus, transient visual loss, hearing impairment, or neuroendocrine dysfunction, are reversible. Future studies should include multiple sites in order to accrue large samples to systematically analyze the aforementioned effects.

Finally, the findings from this study have significant implications for future research and clinical practice. By obtaining presurgical assessment of children's cognitive function, researchers, clinicians, and families will be able to track survivors’ functioning over time. It will be important to compare children's preoperative testing with their postoperative and follow-up testing. Additionally, plotting trajectories of children's functioning will help to identify critical points of intervention and factors related to declines in functioning. It will be important to consider moderators, both risk and protective factors, that will inform intervention efforts to prevent or abate negative effects for brain tumor survivors and their families.

Funding

This research was supported by a gift from an anonymous donor and in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA175840).

Conflict of interest statement. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Mulhern RK, Butler RW. Neurocognitive sequelae of childhood cancers and their treatment. Pediatr Rehabil. 2004;7 (1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sklar CA. Childhood brain tumors. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2002;15 (2):669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States. Statistical Report: Primary Brain Tumors in the United States, 2004–2007. 2012; Published by the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States, Hinsdale, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ness KK, Gurney JG. Adverse late effects of childhood cancer and its treatment on health and performance. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28:279–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355 (15):1572–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Panigrahy A, Bluml S. Neuroimaging of pediatric brain tumors: From basic to advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). J Child Neurol. 2009;24:1343–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brain Tumor Progress Review Group. The National Cancer Institute Brain Tumor Progress Review Group Report. Bethesda, MD: General Books, LLC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robinson KE, Kuttesch JF, Champion JE et al. A quantitative meta-analysis of neurocognitive sequelae in survivors of pediatric brain tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55 (3):525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meyers CA, Brown PD. Role and relevance of neurocognitive assessment in clinical trials of patients with CNS tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1305–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Merchant TE, Conklin HM, Wu S, Lustig RH, Xiong X. Late effects of conformal radiation therapy for pediatric patients with low-grade glioma: Prospective evaluation of cognitive, endocrine, and hearing deficits. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 (22):3691–3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shortman RI, Lowis SP, Penn A et al. Cognitive function in children with brain tumors in the first year after diagnosis compared to healthy matched controls. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61 (3):464–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spiegler BJ, Bouffet E, Greenberg ML, Rutka JT, Mabbott DJ. Change in neurocognitive functioning after treatment with cranial radiation in childhood. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22 (4):706–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stargatt R, Rosenfeld JV, Maixner W, Ashley D. Multiple Factors Contribute to Neuropsychological Outcome in Children with Posterior Fossa Tumors. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2007;32 (2):729–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Correa D. Cognition in brain tumor patients. Current Neurology and Neuroscience reports. 2008;8 (3):242–248. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wechsler D. WPPSI-III: Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence – 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wechsler D. WASI: Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-3rd edition: Administration Manual. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. BRIEF: Behavior. Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gioia GA, Espy KA, Isquith PK. BRIEF-P: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function—Preschool Version. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Knight SJ, Conklin HM, Palmer SL et al. Working memory abilities among children treated for Medulloblastoma: Parent report and child performance. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39 (5):501–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McAuley T, Chen S, Goos L, Schachar R, Crosbie J. J International Neuropsych Society. 2010;16:495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]