Abstract

Introduction:

The current epidemiological data and meta-analyses indicate a bidirectional association between depression and metabolic syndrome (MetS).

Aims:

To assess the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and obesity in drug naïve patients (in current episode) having Recurrent Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Depression.

Method:

This was a single point cross sectional observational study that involved administration of diagnostic and assessment tools and blood investigations. Recruitment for the study was done from a period of September 2008 to august 2009.

Results:

The prevalence of MetS was significantly more in the depression group when compared to healthy controls. The Bipolar depression group had 24% prevalence and recurrent depression group had 26% prevalence as opposed to none in the control group. The prevalence of MetS did not differ significantly amongst the both depression groups. Presence of central obesity was significantly more in the recurrent depression (30%) and Bipolar depression (24%) as compared to controls (8%). There was no statistically significant difference between the two depression subgroups.

Discussion:

Our study adds to the mounting evidence that links the presence of depression and metabolic syndrome. As we had ensured a drug free period of at least 3 months, the findings in our study indicate that the metabolic syndrome observed in our study is independent of drug exposure.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrated significantly more incidence of metabolic syndrome and central obesity in patients of depression than age and sex matched controls.

Key words: Central obesity, depression, metabolic syndrome, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a set of metabolic, anthropometric, and hemodynamic abnormalities including abdominal obesity, impaired lipid profile (lowered high density lipoprotein [HDL] and elevated triglycerides), hypertension, and impaired fasting glucose or insulin resistance.[1] Studies done on Western populations have pegged the prevalence at approximately one-third of the general population.[2,3] Similar studies in Indian populations have found comparable prevalence, ranging from 31 to 41% of studied adults, with greater prevalence in women.[4,5] Needless to say, the risk factors considered under MetS can cause significant physical impairments and adverse health outcomes, Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular morbidity being the best established ones.[6] It has also been associated with increasing the risk of mortality due to cardiovascular events and also an overall, all-cause increase in mortality in the general population.[5,7]

MetS has also been associated robustly with a number of psychiatric illnesses, including and in no ways limited to bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia across multiple studies all around the globe.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]

The current epidemiological data and meta-analyses indicate a bidirectional association between depression and MetS.[16] It should also be noticed that a majority of the studies in this area focus on MetS as a whole, using a dichotomous outcome variable,[17] which strongly varies among different treatment centers and settings. In a British study, it was demonstrated that MetS, and more importantly, its obesity and hyperlipidemia components predicted the development of depressive symptoms over a follow-up period of 6 years.[18] Another meta-analysis involving 5000 depressed subjects calculated the estimated mean prevalence of MetS to be up to 30.5%.[19] In another population-based study, women with MetS in their childhood were found to have increased levels of depressive symptoms in adulthood, and the severity of these symptoms increased in proportion to the duration of exposure to MetS over lifetime.[20] Consequently, studies have found MetS to be a possible predisposing factor for the development of depression, and subsequently, have raised questions whether investigating individual components besides MetS per se would be useful.[16] There has also existed some amount of debate over whether some of the metabolic parameters comprising MetS are more predictive for depressive disorders than others.[16] Of the five components, waist circumference (i.e. abdominal obesity) has been found to be the strongest predictor.[20] Hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL have also been associated to a fair degree, but the association with hyperglycemia and hypertension have been studied to a lesser degree and the results have also been contradictory.[20,21,22]

As was discussed that a bidirectional association has been observed, data also exist regarding the risk for developing MetS in patients of depression. Follow-up studies have found increased the incidence of MetS and its components in patients of depression.

It has also been found that the severity of depression is positively associated with the metabolic outcomes in outpatients and also the use of Anti-depressant medications.[17,23] At the same time, multiple studies have shown poorer outcomes in depressive illnesses in patients with concomitant MetS or obesity.[16,24,25]

To the best of our knowledge, however, we could not find a study where MetS or its parameters were compared among the two major diagnoses of depression, namely the recurrent and the bipolar depression along with healthy controls.

METHODS

This was a single-point cross-sectional observational study that involved administration of diagnostic and assessment tools and blood investigations. Recruitment for the study was done from September 2008 to August 2009 from the adult psychiatric Outpatient Services of our Department. Men and women aged between 18 and 50 years were eligible for the study. We excluded patients above 50 years of age to exclude the effects of age on the metabolic parameters (such as blood glucose, lipid profile, and blood pressure). A drug-free period of 3 months was also ensured as to allow time for the parameters of MetS, which may be altered by psychotropic medications[26,27] to return to premedication levels. Pregnant or currently lactating women were excluded from the study. We excluded patients with co-morbid physical illnesses (such as coronary artery disease, hypothyroidism, liver or kidney disorders) or receiving medications (including contraceptive pills) that may alter the MetS parameters, and patients with any other co-morbid axis-I disorder were excluded as the current study focused on recurrent and bipolar depression. All the subjects provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. The study comprised three groups, two groups comprised of age and sex matched patients of bipolar depression and recurrent depression. The third group comprised of age and sex matched healthy controls. The subjects were evaluated for the MetS based on the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP/ATP III)[28] criteria.

Assessment of components of metabolic syndrome

Blood pressure was measured using a mercury sphygmomanometer in a well-rested subject in the left arm in the sitting position at two occasions, once at initial physical examination and the other on the following morning, and an average of the two was recorded. The body measurements for height, waist and hip circumference, weight and body mass index were done by the investigator (AB) using standard procedures. Participants were asked to fast overnight, following which 5 ml of venous blood was collected by standard venipuncture, 2 ml transferred to fluoride vial and 3 ml to non-ox vial for estimation of serum glucose and lipid levels, respectively. These vials were transferred to the lab immediately following standard preservation practices, and the sample was centrifuged and analyzed for blood glucose, serum HDL, and serum triglycerides on the same day, using automated analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, UK). The diagnostic criteria that were used for the MetS were the updated NCEP ATP III criteria,[29] which include cut-offs for waist circumference (males ≥90 cm, females ≥80 cm), fasting blood glucose (≥100 mg/dl), triglycerides (≥150 mg/dl), blood pressure (≥135/≥80 mm Hg), and low HDL (males <40 mg/dl and females <50 mg/dl). The NCEP ATP III criteria have ethnic specific cut-offs and these cut-offs are identical to the ones that are recommended for use in Indian population by the expert consensus statement on the issue.[30] Three or more of these parameters have to be abnormal for a diagnosis of MetS to be made in an individual.

Evaluation for psychiatric and physical disorders

The diagnosis of depression was made as per the criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).[31] The subjects were evaluated on the Structure Clinical Interview on DSM-IV-TR[32] for making Axis-I diagnosis of a recurrent depression or bipolar depression in accordance with and also to rule out any other psychiatric co-morbidity. The included participants were rated on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)[33] and Clinical Global Impression Scale[34] (only Severity scale was used as it was a single point study). The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale[35] was used to assess the participants’ psychological, social, and occupational functioning.

Statistical analyses

The three participant groups were compared on the sociodemographic variables including age, gender, marital status, domicile, religion, and monthly family income using the Pearson Chi-squared test. The numbers of subjects having MetS and central obesity in each group were compared using the Pearson Chi-squared test, and the correlation between waist circumference and severity of depression on HAM-D was assessed by calculating Pearson's Co-relation coefficient. The data were tabulated and results were calculated using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 14.0.0 for windows.

RESULTS

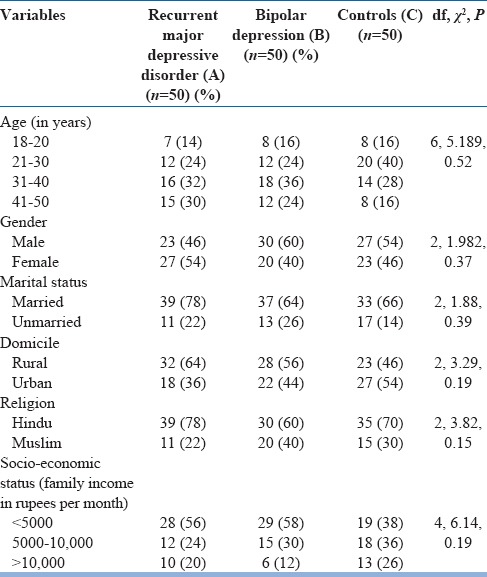

Crude demographic and clinical variables of the three groups are shown in Table 1. No statistically significant difference exists between the groups. Majority of the patients were males, between ages 31 and 40 years, married, and from rural background and lower socioeconomic class.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic details of the sample

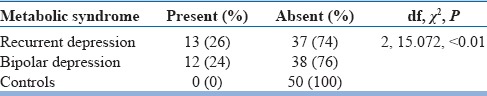

The presence of MetS is shown in Table 2. The prevalence of MetS was significantly more in the depression group when compared to healthy controls. The bipolar depression group had 24% prevalence and recurrent depression group had 26% prevalence as opposed to none in the control group. The prevalence of MetS did not differ significantly among both the depression groups.

Table 2.

Presence of metabolic syndrome

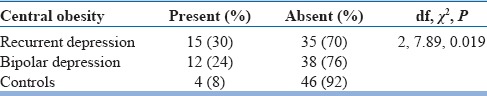

Presence of central obesity was significantly more in the recurrent depression (30%) and bipolar depression (24%) as compared to controls (8%). There was no statistically significant difference between the two depression subgroups [Table 3].

Table 3.

Presence of central obesity

The waist circumference was also positively correlated with the severity of depressive symptoms as measured on the HAM-D scale (r = 0.291; P = 0.003).

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that MetS was more prevalent in the patients suffering from depressive episode when compared to healthy controls (P < 0.01). While no subject from the control group had MetS, the difference among the two patient groups was not statistically significant. As we had ensured a drug-free period of at least 3 months, the findings in our study indicate that the MetS observed in our study is independent of drug exposure.

Our study adds to the mounting evidence that links the presence of depression and MetS. In the studies done in the Western populations, investigators have found that a current or lifetime diagnosis of depression increases the risk of MetS.[36] Similarly, in studies comparing patients suffering from depression to healthy controls, increased prevalence of MetS was established.[10,11,13,15] In a meta-analyses on MetS and metabolic abnormalities in patients of depression, comprising 18 studies and 5531 subjects, a mean prevalence of 29.7% was reported.[19] This is comparable to the prevalence found in our patients group (26% in recurrent depression and 24% in bipolar depression group). In another study done on drug-naive patients[37] of depression in India, the prevalence of MetS was found to be significantly higher (37.2%) than healthy controls.

While the association between MetS and depression has been firmly demonstrated, the question of causality, however, still stands inadequately answered. There have been studies on the predisposing role of MetS in depressive disorder. A longitudinal study found that subjects with no psychiatric illness and MetS at baseline were twice more likely to develop depressive symptoms during follow-up than their healthy matched controls.[38] This area is of particular concern as if MetS is established as a predisposing factor, its subsequent prevention, and treatment can also be an important step in the prevention of depression.

Nevertheless, the high co-occurrence of depressive symptoms and MetS is highly indicative of a patho-physiological overlap between the two conditions. While the conclusive evidence and mechanism are yet to be elucidated, the proposed hypotheses include elevation in cortisol secretion due to increased activity of HPA axis, neuro-inflammatory processes involving interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein, increased oxidative stress, autonomic dysregulation in form of increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic system responses, and insulin resistance.[19] It should also be remembered that even if the biological processes are important, equally relevant are the lifestyle and socio-economic factors.[13,39] Depression is known to be associated with increasing odds of developing hyperglycemia and hypertriglyceridemia, which may be attributed to the biological process of depression or the associated changes in the diet and physical activity.[40]

We also compared the individual metabolic abnormalities in our participant groups. In our study, visceral obesity (increased waist circumference) was significantly more in the recurrent depression patient groups compared to the healthy controls. This has been reported in many of the studies.[24,37,41,42,43,44] Over the last 10–15 years, an increasing amount of literature has appeared, examining the cross-sectional and longitudinal relationship between the constructs of obesity and depression. While a large number of these studies have defined obesity by BMI, which is an indicator of general fat distribution.[40,45,46,47] The abdominal fat or visceral obesity is known to have a greater impact on the immune system and is considered to have greater predictive value for health outcomes.[48] In addition, as discussed earlier, association between central obesity as a MetS variable has a stronger association with depression,[20] thus studies have made use of abdominal obesity as a variable. As reported in a meta-analysis, a significant degree of association between obesity and depression has been found in multiple community studies.[45] Its findings were in concordance with the meta-analysis on relation of abdominal obesity with depression where the risk of having depression was increased by more than 50% in obese men and women.[48]

Furthermore, the mean waist circumference of recurrent major depressive disorder (77.18 ± 8.79) and bipolar depression (77.68 ± 9.16) was significantly higher (P = 0.03; P = 0.02) as compared to control group (73.92 ± 6.66). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of obesity between the recurrent depression and the bipolar depression group. However, association of obesity has been more robustly defined with bipolar disorder than depression.[49,50]

An important confounding factor in many studies has been the medications for the treatment of bipolar disorder, such as lithium, valproic acid, and atypical antipsychotics that have been associated with weight gain.[51,52,53,54,55] Some of the unanswered questions include whether severity of depression influences the obesity. There has been some evidence that depression increases with severity of obesity.[56,57] In our sample too, we found a positive correlation, albeit small between the severity of depression on HAM-D and the mean waist circumference.

A very important query in relation to obesity, as with MetS, is the existence of a causal link. There have been some studies that have found evidence that depression predicts development of obesity,[58,59] a recent met-analysis has also concluded that depression can predict development of obesity later in life.[46] On the other hand, there have been studies that have found that obesity may predict the development of depression.[60,61]

Nevertheless, the findings of our study are clinically important, as it is imperative for us as clinicians to identify patients having or predisposed to MetS and obesity. While some longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have found gender to be a factor, meta-analyses have not shown any significant differences, indicating that both the sexes need equal attention. It is also important because depression and associated biological/psychological processes may take more salience than the known risk factor of age for MetS,[62] as suggested by the age of our sample, which was on the lower side. This finding was also found in the meta-analyses on the subject.[19,48] Thus, it can be suggested that individuals with depressive disorder can be screened for MetS risk factors, and this approach should not just be reserved for patients of advanced age, but also the younger age group patients. Another important step in this direction can be the management of these individuals as a multi-disciplinary collaborative effort between the psychiatrist and physicians, with psychoeducation and motivation for lifestyle improvements and use of lower risk medications or medications to reduce the weight or metabolic abnormalities.[63]

Our study did have a number of limitations. Our sample size was small and thus results may not be generalized to general population. In addition, the cross-sectional design of the study is not suitable to demonstrate prognostic or predictive features of the MetS or its variables. Longitudinal studies are required to study these areas and also the impact of intervention on metabolic parameters in patients suffering from depression.

CONCLUSION

In the current study, the overall prevalence of MetS was found to be 25% in the patients group (24% in recurrent depression and 26% in bipolar depression), which was significantly more than the healthy age- and sex-matched controls. Central obesity was also present in significantly higher proportion of the patient groups, and the waist circumference was found to be positively associated with the severity of depressive symptoms.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:629–36. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta R, Deedwania PC, Gupta A, Rastogi S, Panwar RB, Kothari K. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an Indian urban population. Int J Cardiol. 2004;97:257–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Satyavani K, Sivasankari S, Vijay V. Metabolic syndrome in urban Asian Indian adults – A population study using modified ATP III criteria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;60:199–204. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(03)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford ES. Risks for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes associated with the metabolic syndrome: A summary of the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1769–78. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grover S, Nebhinani N, Chakrabarti S, Avasthi A, Basu D, Kulhara P, et al. Cardiac risk factors and metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia admitted to a general hospital psychiatric unit. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56:371–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.146520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malhotra N, Kulhara P, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. A prospective, longitudinal study of metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:653–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahl KG, Greggersen W, Schweiger U, Cordes J, Balijepalli C, Lösch C, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in unipolar major depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262:313–20. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter N, Juckel G, Assion HJ. Metabolic syndrome: A follow-up study of acute depressive inpatients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260:41–9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattoo SK, Singh SM. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in psychiatric inpatients in a tertiary care centre in North India. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIntyre RS, Rasgon NL, Kemp DE, Nguyen HT, Law CW, Taylor VH, et al. Metabolic syndrome and major depressive disorder: Co-occurrence and pathophysiologic overlap. Curr Diab Rep. 2009;9:51–9. doi: 10.1007/s11892-009-0010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Hert M, Schreurs V, Vancampfort D, van Winkel R. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: A review. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:15–22. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gil K, Radzillowicz P, Zdrojewski T, Pakalska-Korcala A, Chwojnicki K, Piwonski J, et al. Relationship between the prevalence of depressive symptoms and metabolic syndrome. Results of the SOPKARD project. Kardiol Pol. 2006;64:464–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marazziti D, Rutigliano G, Baroni S, Landi P, Dell’Osso L. Metabolic syndrome and major depression. CNS Spectr. 2014;19:293–304. doi: 10.1017/S1092852913000667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luppino FS, Bouvy PF, Giltay EJ, Penninx BW, Zitman FG. The metabolic syndrome and related characteristics in major depression: Inpatients and outpatients compared: Metabolic differences across treatment settings. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:509–15. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akbaraly TN, Kivimäki M, Brunner EJ, Chandola T, Marmot MG, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and depressive symptoms in middle-aged adults: Results from the Whitehall II study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:499–504. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vancampfort D, Correll CU, Wampers M, Sienaert P, Mitchell AJ, De Herdt A, et al. Metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of prevalences and moderating variables. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2017–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pulkki-Råback L, Elovainio M, Kivimäki M, Mattsson N, Raitakari OT, Puttonen S, et al. Depressive symptoms and the metabolic syndrome in childhood and adulthood: A prospective cohort study. Health Psychol. 2009;28:108–16. doi: 10.1037/a0012646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaysina D, Pierce M, Richards M, Hotopf M, Kuh D, Hardy R. Association between adolescent emotional problems and metabolic syndrome: The modifying effect of C-reactive protein gene (CRP) polymorphisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:750–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blank K, Szarek BL, Goethe JW. Metabolic abnormalities in adult and geriatric major depression with and without comorbid dementia. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2010;12:456–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Reedt Dortland AK, Giltay EJ, van Veen T, Zitman FG, Penninx BW. Metabolic syndrome abnormalities are associated with severity of anxiety and depression and with tricyclic antidepressant use. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122:30–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinder LS, Carnethon MR, Palaniappan LP, King AC, Fortmann SP. Depression and the metabolic syndrome in young adults: Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:316–22. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000124755.91880.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-Toro M, Vicens-Pons E, Gili M, Roca M, Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Vives M, et al. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and Mediterranean diet: Impact on depression outcome. J Affect Disord. 2016;194:105–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Hert MA, van Winkel R, Van Eyck D, Hanssens L, Wampers M, Scheen A, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotic medication. Schizophr Res. 2006;83:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.12.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McIntyre RS, Park KY, Law CW, Sultan F, Adams A, Lourenco MT, et al. The association between conventional antidepressants and the metabolic syndrome: A review of the evidence and clinical implications. CNS Drugs. 2010;24:741–53. doi: 10.2165/11533280-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the national cholesterol education program adult treatment panel III guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:720–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misra A, Chowbey P, Makkar BM, Vikram NK, Wasir JS, Chadha D, et al. Consensus statement for diagnosis of obesity, abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome for Asian Indians and recommendations for physical activity, medical and surgical management. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009;57:163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition: DSM-IV-TR ®. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams, Janet BW. (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, patient Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guy W, editor. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Psychiatric Association. Global assessment of functioning scale. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldbacher EM, Bromberger J, Matthews KA. Lifetime history of major depression predicts the development of the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged women. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:266–72. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318197a4d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grover S, Nebhinani N, Chakrabarti S, Avasthi A, Kulhara P. Metabolic syndrome in drug-naïve patients with depressive disorders. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:167–73. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.116247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koponen H, Jokelainen J, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Kumpusalo E, Vanhala M. Metabolic syndrome predisposes to depressive symptoms: A population-based 7-year follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:178–82. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Eliasziw M. A longitudinal community study of major depression and physical activity. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:571–5. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:220–9. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeuchi T, Nakao M, Nomura K, Yano E. Association of metabolic syndrome with depression and anxiety in Japanese men. Diabetes Metab. 2009;35:32–6. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaccarino V, McClure C, Johnson BD, Sheps DS, Bittner V, Rutledge T, et al. Depression, the metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:40–8. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815c1b85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunbar JA, Reddy P, Davis-Lameloise N, Philpot B, Laatikainen T, Kilkkinen A, et al. Depression: An important comorbidity with metabolic syndrome in a general population. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2368–73. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herva A, Räsänen P, Miettunen J, Timonen M, Läksy K, Veijola J, et al. Co-occurrence of metabolic syndrome with depression and anxiety in young adults: The Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:213–6. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000203172.02305.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A, Penninx B, Zitman F, Cuijpers P. Depression and obesity: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:230–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blaine B. Does depression cause obesity? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies of depression and weight control. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:1190–7. doi: 10.1177/1359105308095977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Atlantis E, Baker M. Obesity effects on depression: Systematic review of epidemiological studies. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:881–91. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu Q, Anderson D, Lurie-Beck J. The relationship between abdominal obesity and depression in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2011;5:e267–360. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elmslie JL, Silverstone JT, Mann JI, Williams SM, Romans SE. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:179–84. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McElroy SL, Frye MA, Suppes T, Dhavale D, Keck PE, Jr, Leverich GS, et al. Correlates of overweight and obesity in 644 patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:207–13. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, Chandler LP, Cappelleri JC, Infante MC, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: A comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1686–96. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keck PE, McElroy SL. Bipolar disorder, obesity, and pharmacotherapy-associated weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1426–35. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Theisen FM, Linden A, Geller F, Schäfer H, Martin M, Remschmidt H, et al. Prevalence of obesity in adolescent and young adult patients with and without schizophrenia and in relationship to antipsychotic medication. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35:339–45. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Avasthi A, Aggarwal M, Grover S, Khan MK. Research on antipsychotics in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(Suppl 1):S317–40. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gautam S, Meena PS. Drug-emergent metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia receiving atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:128–33. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.82537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scott KM, Bruffaerts R, Simon GE, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, de Girolamo G, et al. Obesity and mental disorders in the general population: Results from the world mental health surveys. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:192–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Onyike CU, Crum RM, Lee HB, Lyketsos CG, Eaton WW. Is obesity associated with major depression? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:1139–47. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roberts RE, Strawbridge WJ, Deleger S, Kaplan GA. Are the fat more jolly? Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:169–80. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pine DS, Cohen P, Brook J, Coplan JD. Psychiatric symptoms in adolescence as predictors of obesity in early adulthood: A longitudinal study. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1303–10. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.8.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herva A, Laitinen J, Miettunen J, Veijola J, Karvonen JT, Läksy K, et al. Obesity and depression: Results from the longitudinal Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:520–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roberts RE, Deleger S, Strawbridge WJ, Kaplan GA. Prospective association between obesity and depression: Evidence from the Alameda County study. Int J Obes. 2003;27:514–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.North BJ, Sinclair DA. The intersection between aging and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2012;110:1097–108. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.246876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Hert M, Dekker JM, Wood D, Kahl KG, Holt RI, Möller HJ. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:412–24. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]