Abstract

Background:

Very few studies from India have studied stigma experienced by patients with schizophrenia.

Aim of the Study:

To study stigma in patients with schizophrenia (in the form of internalized stigma, perceived stigma and social-participation-restriction stigma) and its relationship with specified demographic and clinical variables (demographic variables, clinical profile, level of psychopathology, knowledge about illness, and insight).

Materials and Methods:

Selected by purposive random sampling, 100 patients with schizophrenia in remission were evaluated on internalized stigma of mental illness scale (ISMIS), explanatory model interview catalog stigma scale, participation scale (P-scale), positive and negative syndrome scale for schizophrenia, global assessment of functioning scale, scale to assess unawareness of mental disorder, and knowledge of mental illness scale.

Results:

On ISMIS scale, 81% patients experienced alienation and 45% exhibited stigma resistance. Stereotype endorsement was seen in 26% patients, discrimination experience was faced by 21% patients, and only 16% patients had social withdrawal. Overall, 29% participants had internalized stigma when total ISMIS score was taken into consideration. On P-scale, 67% patients experienced significant restriction, with a majority reporting moderate to mild restriction. In terms of associations between stigma and sociodemographic variables, no consistent correlations emerged, except for those who were not on paid job, had higher participation restriction. Of the clinical variables, level of functioning was the only consistent predictor of stigma. While better knowledge about the disorder was associated with lower level of stigma, there was no association between stigma and insight.

Conclusion:

Significant proportion of patients with schizophrenia experience stigma and stigma is associated with lower level of functioning and better knowledge about illness is associated with lower level of stigma.

Key words: Correlates, insight, knowledge about illness, schizophrenia, stigma

INTRODUCTION

As a severe mental disorder that usually starts in late adolescence or early adulthood and causes continued disability and poor quality of life, persons with schizophrenia have to cope not only with their symptoms but also with many highly prevalent negative societal attitudes constituting stigma.

Stigma is understood as “a deeply discrediting attribute” and that reduces the bearer “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one.”[1] In relation to mental illness, other researchers consider stigma as a form of deviance that leads others to judge an individual as not having legitimacy to participate in a social interaction. This occurs because of a perception that they lack the skills or abilities to carry out such an interaction and is also influenced by judgments about the dangerousness and unpredictability of the person.[2]

The common impacts of stigma associated with mental disorders include social exclusion, unsatisfactory housing, and restricted opportunities for employment and education, which impair the quality of life. Many people hesitate to use mental health services because they do not want to be labeled as a “mental patient” and want to avoid the negative consequences connected with stigma.[3] It has also been shown that stigma is significantly related to mental health. Self-stigmatization leads to low self-esteem and low self-efficacy and discrimination contributes to failure to pursue work and household activities. Other consequences of stigma include reluctance for marital relations[4] and poor quality of care for physical illness among people with psychiatric ailments.[5] A recent systematic review,[6] reported that perceived/experienced stigmas predict higher depression, more social anxiety, more secrecy, and withdrawal as coping strategies, along with lower quality of life, lower self-efficacy, lower self-esteem, lower social functioning, less support, and less mastery.

Many studies have evaluated the relationship of stigma with sociodemographic variables. Overall, the findings regarding the significance of sociodemographic variables are inconsistent and the predictive power of these variables on stereotypical thinking and discriminating behavior is relatively low.[6,7] Higher perceived stigma has been reported to be associated with early phases of illness, longer duration of illness, and with higher number of hospitalizations.[8] Stigma has been reported to have a paradoxical relationship with insight, i.e., the patients with poor insight perceive less stigma; however, as the insight improves, there is increased belief in incurability and incapacity of achieving social role, lowered self-esteem, and more internalized stigma. A higher level of stigma has been shown to be related to lower subjective quality of life and younger age of onset.[9] However, data suggest that quality of life is inversely associated with personal stigma.[6] Among the various symptoms, positive symptoms, depression, and general psychopathology have been reported to have significant positive correlation with personal stigma[6] and negative symptoms, social functioning, and self-efficacy are correlated positively with internalized stigma.[10]

Although there are many studies from different parts of the world, there are only a handful of studies from India, which have evaluated stigma experienced by the patients with schizophrenia.[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] Some of these studies have discussed the urban-rural differences and male-female differences in the perception and impact of stigma.[12,14,18] Other studies have evaluated the relationship of stigma with insight.[13] Studies have also focused on the context, in which stigma is perceived by patients, possible causes for the stigma, experienced stigma, impact of stigma, and correlates of stigma.[11,16,17] It is evident that research on stigma associated with schizophrenia is mostly from southern India. Studies from India have not looked at the relationship of stigma with clinical factors such as attitude toward medication and medication compliance.

Studies also suggest that the nature, determinants, and consequences of stigma vary across culture and region. Hence, there is a need for studies to understand the stigma specific to a particular region to plan intervention. Better understanding and identification of determinants may suggest ways to reduce stigma and help prevent its adverse consequences.

In this background, this study is aimed to study (1) the stigma perceived by patients with schizophrenia in the form of internalized stigma, perceived stigma, and stigma in the form of participation restriction in various spheres of life; (2) the relationship of stigma with sociodemographic variables, clinical variables, level of psychopathology, knowledge about illness, and insight.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study conducted at the psychiatry outpatient services of a tertiary care hospital in North India. All the patients were recruited after obtaining written informed consent and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute.

The sample, selected by purposive random sampling, comprised of 100 patients with schizophrenia as per the DSM IV (as assessed by Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview[19]), in remission (as defined by Andreasen et al.,[20]), aged between 18 and 65 years, with illness of at least 2 years duration, and be able to read Hindi. Those with organic brain syndrome, mental retardation, and comorbid drug dependence were excluded from the study. Stigma was assessed using three scales as these are considered to assess different aspects of stigma.

Patients were evaluated on the following instruments:

Internalized stigma of mental illness scale

Internalized stigma of mental illness scale (ISMIS) is a tool to assess self-stigma/internalized stigma, from the perspective of stigmatized individuals. It comprises 29 questions with 4 answering options (strongly disagree - 1, disagree - 2, agree – 3, and strongly agree - 4) divided into five components (alienation, stereotype endorsement, perceived discrimination, social withdrawal, and stigma resistance). A higher score reflects a higher level of self-stigma. A cutoff of 2.5 is suggested to be an indicator of presence or absence of stigma.[21,22]

Explanatory model interview catalog stigma scale

Explanatory model interview catalog (EMIC) stigma scale is a tool to assess anticipated/perceived stigma, from the perspective of stigmatized individual. It has 15 questions, with four answering options, with higher score indicating higher perceived stigma.[23] As a generic application, it can be used for different health conditions.

The participation scale

It uses an interview to assess the subjective impact of stigma in terms of the severity of participation restrictions. The scale has generic application and can be used for different health conditions. It has 18 questions, with two levels of the answering options. The first level has five options: not satisfied, yes, sometimes, no, and irrelevant. If the first level options are yes or sometimes, the second level has four options: no problem (1), small problem (2), medium problem (3), and large problem (5). A high total score indicates a high level of participation restriction. In several studies, a cutoff point of 12 was found to indicate what is “normal” (not having significant participation restriction).[24]

Positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia

It was used to assess the level of residual psychopathology.[25]

Global assessment of functioning scale

This was used to assess the level of functioning of the patients.[26]

Scale to assess unawareness of mental disorder

An abbreviated version of the scale to assess unawareness of mental disorder (SUMD) was used to evaluate the level of insight. The SUMD utilizes a semi-structured interview to rate discrete and global aspects of insight. It is rated on a five-point scale (1-5), with lower scores indicating better insight. It has satisfactory convergent and criterion validities and can be used reliably with minimum training. It has been used widely among patients with schizophrenia.[27]

Knowledge of mental illness scale

Knowledge of mental illness (KMI) scale assesses the patient's knowledge about their illness and medications. It consists of five items exploring knowledge about diagnosis, symptomatology, causes, medications, and treatment; each item is rated on a three-point scale, and higher scores indicate better knowledge about the illness.[28]

Data were analyzed using SPSS-14 (SPSS for Windows, Version 14.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc.). The analysis was performed by frequency/percentage for categorical variables and by mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. Comparisons were made using Student's t-tests, Mann–Whitney-U tests, and Chi-square test. The relationship of stigma with other variables was studied using Pearson's correlation coefficient, t-tests, and Chi-square test. In terms of multiple correlations and comparisons, P < 0.01 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant. Multiple and binary logistic regression analyses were carried out to study the relationship of stigma with other variables.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic profile of patients

The mean age of the study sample was 36.8 (standard deviation [SD] 12.1; range 18–65) years. Males (n = 54) outnumbered the females (n = 46) in the study sample. A majority of the patients were currently married (n = 61), not on a paid employment (n = 58), Hindu by religious (n = 69), from nuclear families (n = 56), urban locality (n = 58), and from middle socioeconomic status (n = 59). The mean number of years of education of patients was 10.5 (SD: 4.4; range 0–17).

Clinical profile of the patient

The most common diagnostic subtypes were paranoid (63%) and undifferentiated schizophrenia (34%). The mean age of onset was 26.5 (SD: 8.9; range 12–53) years and the mean duration of illness was 10.2 (SD: 8.1; range 2–40) years. The mean number of hospital visits in 3 months before the study intake was 1.2 (SD: 0.8). The mean total PANSS score was 34.4 (SD: 2.1; range 31–41). The mean global assessment of functioning (GAF) score was 92.9 (SD: 4.3; 80–98).

Stigma experienced by patients

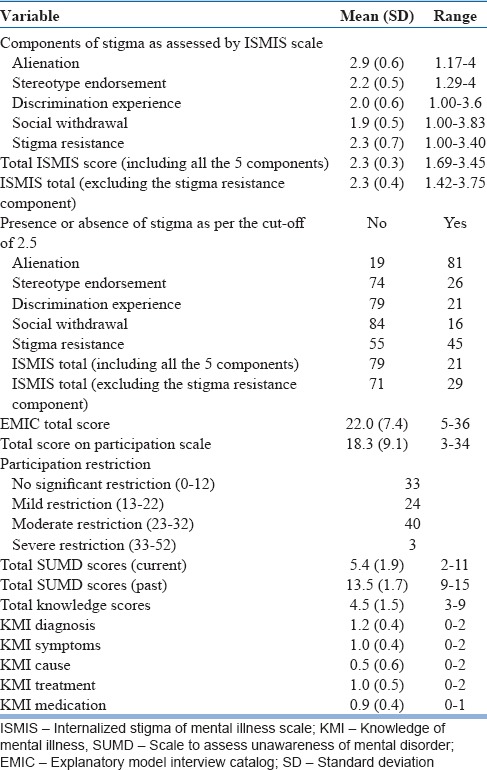

For the components of ISMIS, the mean score was highest for alienation, followed by stigma resistance, stereotype endorsement, and discrimination experience, and the lowest for the component of social withdrawal.

When the cutoff of 2.5 was used to categorize the presence or absence of stigma, 81% patients reported alienation and 45% patients reported stigma resistance. Other details are shown in Table 1. The total mean score on EMIC stigma scale was 22.0 (SD: 7.4) and on participation scale (P-scale) was 18.3 (SD: 9.1). When the cutoff of 12 was used to assess the level of restriction due to stigma, 67% patients reported experiencing significant restriction, with a majority reporting moderate to mild restriction [Table 1].

Table 1.

Stigma, insight, and knowledge about illness (n=100)

Insight, knowledge about illness

As shown in Table 1, compared to the past level of insight, for the current level of assessment, the SUMD total scores were lower. The mean total score on the scale assessing the knowledge about illness was 4.5 (SD: 1.5).

Association between stigma and other variables

Sociodemographic variables

There was no significant correlation between age and education with total ISMIS score, EMIC score, and P-scale score. However, age of the patients correlated positively with the stigma resistance component (r = 0.258**, P = 0.01). There was no significant difference in the mean total score on ISMIS, EMIC, and P-scales between patients from different socioeconomic classes, type of family (nuclear vs. nonnuclear), religions, and localities. There was no significant difference in the total mean ISMIS and EMIC scores across the two genders. However, compared to males, females had significantly higher scores in the components of stereotype endorsement (t = 3.72***, [P < 0.001]) and total P-scale score (t = 4.45***, [P < 0.001]). In contrast, males had significantly higher scores in the component of stigma resistance (t = 3.86***, (P < 0.001]). Those who were not wage earners had significantly lower scores in the components of social withdrawal (t = 2.68**, [P = 0.009]), total P-scale score (t = 15.03***, [P < 0.001]). However, those who were employed had significantly higher scores in the component of stigma resistance (t = 2.88**, [P = 0.005]).

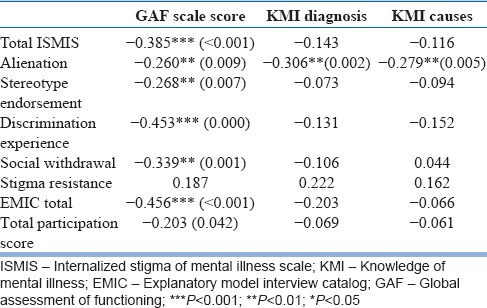

Clinical variables of patients

As shown in Table 2, maximum numbers of correlations were for GAF score with all except one component (i.e., stigma resistance) and total ISMIS and total EMIC. The correlation between GAF score and total participation scores was not significant when the significance level of 0.01 was used. There were no significant correlations between different stigma scores and age of onset, duration of illness, duration of current treatment, and PANSS score. There was no difference in the stigma experienced by those with paranoid and other types of schizophrenia.

Table 2.

Association between clinical variables and stigma experienced by patients (n=100)

In terms of knowledge about illness, KMI diagnosis item score and KMI causes item score correlated negatively with alienation component of ISMIS scale. There was no significant correlation between the current level of insight and stigma.

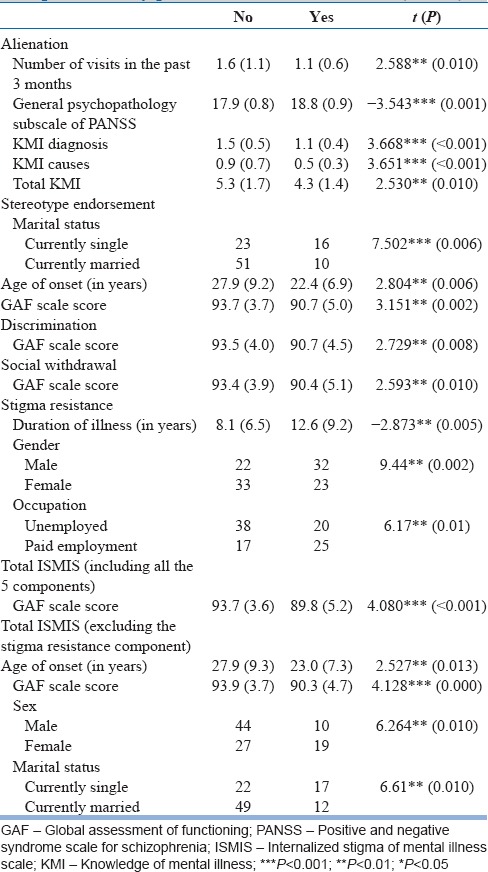

Factors associated with presence or absence of stigma as per internalized stigma of mental illness scale

Using a cutoff of 2.5 to categorize the presence or absence of stigma, the study sample was divided by total ISMIS score. Maximum numbers of differences were noted for the alienation component. Those who experienced alienation had significantly lesser number of visits, higher level of general psychopathology as per PANSS, lower scores for knowledge about diagnosis and causes, and total knowledge score.

For other components, i.e., stereotype endorsement, discrimination, social withdrawal, and stigma resistance, significant difference was seen on GAF. In addition for the component of stereotype endorsement, a significant difference was seen for age of onset and marital status with those experiencing the same had significantly lower age of onset and was more often single. For the component of stigma resistance, those with stigma resistance had significantly longer duration of illness. On total ISMIS score, those who experienced stigma had lower GAF score. On ISMIS total after excluding the component of stigma resistance, those who experienced stigma had lower age of onset, had lower level of functioning as assessed by GAF score, were more often females and currently single [Table 3].

Table 3.

Association between internalized stigma experienced by patients and other variables (n=100)

Factors associated with significant restriction experienced by the patients as assessed by participation scale

Those who experienced significant restriction were younger (34.4 [SD: 11.8] vs. 41.2 [SD: 10.8]; t = 2.80** [P = 0.006]), females (87.9% vs. 37.3%; χ2 = 20.7*** [P < 0.001]), and not on paid employment (14.9% vs. 96.9%; χ2 = 57.8*** [P < 0.001]). There was no difference on other variables.

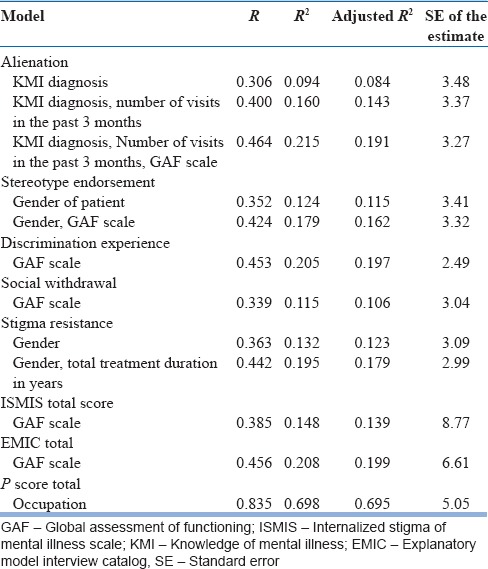

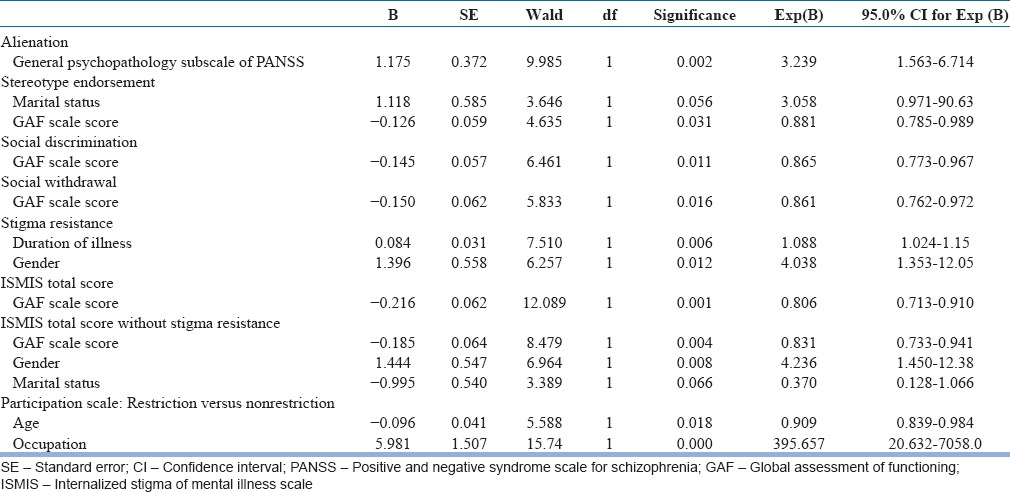

Regression analysis

Both multiple and binary logistic regression analyses were performed to study the relationship of stigma with other variables.

The variables with significant associations were entered into the multiple regression analysis with enter method. Alienation component was explained by KMI diagnosis, number of visits in the past 3 months, and GAF score. All these variables explained 19.1% of variance.

Patients’ gender alone explained 11.5% of variance of the component of stereotype endorsement. The variance increased to 16.2% when gender of the patient and level of functioning by GAF score were taken into account. Other variables did not have any significant effect on the variance of stereotype endorsement.

GAF score explained 19.7% of the variance in the component of discrimination experience and 10.6% of the variance in the component of social withdrawal. Gender and total duration of treatment in years explained 17.9% of variance in the stigma resistance component. Only 13.9% of the variance of ISMIS total could be explained by GAF score. Similarly, 19.9% of variance of EMIC total score was explained by GAF score. Only one variable (occupation) explained maximum variance of stigma by P-scale (69.5%) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Multiple regression analysis showing the variance in the stigma score of patient explained by other variables (n=100)

For the binary logistic regression analysis, all the variables with significant differences on various stigma categories were entered into the analysis. The presence or absence of stigma as per the various components of ISMIS, total ISMIS score, and total ISMIS score without the component of stigma resistance and presence or absence of restriction in participation were entered as dependent variable, and the variables which differed significantly in the comparison analysis were entered as covariates to calculate the odds ratio.

For alienation, odds ratio was significant and more than one for general psychopathology score. For the components of stereotype endorsement, social discrimination, and social withdrawal, GAF score was the only significant predictor. For the component of stigma resistance and ISMIS total score without stigma resistance, the odds ratio was 4 for gender. GAF score was significant predictor of ISMIS score on the both inclusion and exclusion of stigma resistance component. For the participation restriction as assessed by P-scale, the odds ratio for occupation was 395.65 [Table 5].

Table 5.

Binary logistic regression analysis showing predictors of stigma (n=100)

DISCUSSION

People with mental illness have to deal with the double jeopardy. On the one hand, they have to struggle with their symptoms and disability arising from the disorder, and on the other hand, they have to face the societal stereotypes about the illness. These stereotypes influence the behavior of the patient and are understood as stigma. Stigma is a major barrier in the management of various mental disorders.

Studies suggest that the nature, determinants, and consequences of stigma vary across culture. Hence, to overcome stigma, it is important to understand it in its cultural context. The present study attempted to evaluate the personal stigma in the form of self-sigma, anticipated stigma, and impact of stigma in participation in work-related activities, social activities, and peer relationship using standardized scales. This study included 100 patients with schizophrenia who were in remission. The phase of remission was specifically selected to rule out the influence of florid psychopathology (we did not come across any study where only patients in remission were included). The illness had to be of at least 2 years duration so that the patients could better relate their experience and perception about stigma. Those with comorbid drug dependence were excluded as drug dependence itself is associated with significant stigma.

Stigma experienced by patients

Stigma was assessed by three well-validated instruments (ISMIS, EMIC and P-scales), used in earlier studies on stigma with schizophrenia[29,30,31,32,33] and including in India for stigma with mental as well as physical illnesses.[34] With some overlap, these scales evaluate different aspects of stigma experienced by patients with schizophrenia. ISMIS focuses on self-stigma, EMIC focuses on anticipated/perceived stigma, and P-scale assesses subjectively the severity of participation restrictions in work, social activities, and peer relationship. None of the previous studies have evaluated these three components of stigma together in the same study sample of schizophrenia; thus, this can be considered as a methodological advancement.

Self-stigma refers to the alienation of patients due to the process of internalization of stigma. It is thought to have cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to perceived or experienced stigma. In our study, based on the ISMIS total score cutoff, 21% participants experienced stigma. This finding cannot be compared with other studies for two main reasons. One, the previous studies across the world have used different instruments to evaluate personal stigma. Two, our sample being in remission, how much the stigma reported in other studies is affected by ongoing psychopathology, remains questionable. However, when we compare our findings with studies reporting ISMIS-assessed self-stigma in the range of 29.4–41.7% of participants,[35,36] the prevalence of self-stigma in our study was about one half or toward the lower end. However, in terms of the components of stigma, prevalence rate of 81% for alienation in our study is higher than the range of 27.9–77% reported in ISMIS-based studies from the West.[37,38,39] This suggests that compared to other aspects of stigma, the alienation, which reflects a feeling of social devaluation, is more prevalent in our society. About 26% prevalence of stereotype endorsement in our study was within the earlier reported range of 15.2–42%.[37,38,39] Stereotype endorsement reflects agreement of the patient with negative stereotypes of mental illness prevailing in the society in general. Similarity of its prevalence across different cultures suggests that although the negative stereotypes may be specific to a culture, the reaction of mentally ill subjects is similar across different cultures. As other studies have consistently not described the prevalence of stigma in terms of other components of ISMIS, i.e., discrimination experience and social withdrawal, we have no data to compare our findings with, but our findings suggest that 21% and 16% of patients experience stigma in these areas too. For stigma resistance, the existing literature from the West suggests a prevalence rate of 32.5–84%;[37,38,39] our finding of prevalence of 45% is within this range.

On comparing mean scores of various components of ISMIS and total ISMIS score with the previous studies based on the ISMIS, the mean scores for the components of stereotype endorsement, discrimination, social withdrawal, and stigma resistance are comparable with the existing literature.[10,35,36,40,41] However, in the present study, the mean score for the component of alienation was 2.9, which is relatively higher than the reported range of 2.13–2.53 in literature, suggesting that possibly patients in Indian setting face more alienation.

Previous studies which have evaluated stigma in patients with schizophrenia have not used EMIC stigma scale and P-scale, hence, we have no data to compare our findings with. However, our findings are comparable to the findings of EMIC stigma scale or P-scale-assessed stigma with leprosy, tuberculosis, and HIV in Indian setting.[42,43] Our finding of 67% patients with schizophrenia experiencing difficulty in work related activities, social activities, and peer relationships suggests that besides the rehabilitation and vocational guidance, the clinicians should focus on the social skills training of patients with schizophrenia to reduce the participatory restriction.

Correlates of stigma

A recent review concluded that studies evaluating stigma with schizophrenia have not reported any consistent sociodemographic correlates of stigma.[6] Our study also failed to find many significant associations between stigma and various sociodemographic variables. However, we recorded some gender differences for alienation, which can be understood from the perspective of different gender roles in traditional Indian culture. Another interesting correlation noted in our study was that of age and stigma resistance, which suggests that with increasing age - possibly experienced patients learn how to fight the cultural myths and stigma associated with their schizophrenia. Another important association, the strongest in our study, was between employment status and restriction in participation. This finding suggests that since being a wage earner possibly boosts the self-esteem of the patients with schizophrenia and provides them status in the society, it is associated with lower level of participatory difficulties in other spheres of life. This finding finds further support in the fact that being a wage earner is also associated positively with stigma resistance, suggesting that it helps in fighting the stigma.

In terms of clinical correlates, our study noted very few associations between the level of psychopathology and stigma. Only higher general psychopathology score on PANSS was associated with the presence of alienation. This finding is supported by earlier studies.[44] Possible lack of such associations in our study could be due to the inclusion of patients in remission only.

Our finding of most important association between stigma and GAF-assessed level of functioning being similar to the finding of higher level of quality of life and social integration being associated with lower level of stigma suggests that the efforts in clinical management of schizophrenia should be directed not only at symptom removal but should at improving the functioning.

In our study, higher number of visits to the hospital in the past 3 months being associated with lower level of alienation suggests that interaction with the clinicians possibly acts as a big support for the patients to fight with stigma. Our study did not support the relationship of stigma with insight as reported in literature.[45,46,47] As discussed earlier, this could be due to inclusion of patients in remission, who possibly had a high level of insight. On the other hand, our study noted the association between the higher level of knowledge about the disorder, especially the diagnosis and causes, being associated with lower level of internalized stigma. Previous studies have come up with similar findings,[48] and this finding emphasizes the need for proper psychoeducation about the illness.

Comparison with findings from India

How do the findings on stigma in the present study compare to the previous studies from India?

Because of the scales used to measure stigma being different, the comparison with previous studies from India is difficult. However, the following commonalities are noted. Murthy[49] evaluated stigma in 1000 patients in four cities as a part of the Indian initiative of the World Psychiatric Program to reduce the stigma and discrimination because of schizophrenia. Assessment instrument was a semi-structured interview which was developed by a national working group for India by the World Psychiatric Association steering committee.[50] He reported that urban respondents in large centers try to hide their illness hoping to remain unnoticed whereas rural respondents in smaller regions experience greater ridicule, shame, and discrimination as anonymity is more difficult. Another study from Bengaluru, which evaluated the urban rural differences, reported that urban participants felt the need to hide their illness and avoided illness histories in job applications whereas rural participants experienced more ridicule, shame, and discrimination.[14] As we did not carry out the item level analysis of various scales, we cannot comment on their urban rural differences; however, for total scores and ratings of various components, no significant rural urban difference was noted.

Loganathan and Murthy[12,14] also evaluated gender differences for stigma. They noted that while men experienced shame and ridicule and difficulty in getting married, hid their illness from others and in job applications, and were worried what others might think of them; in women, stigma was related to marriage, pregnancy, and childbirth. Both men and women revealed certain cultural myths about their illness and how these affected their lives in a negative way.[12,14] Another study from India,[17] which evaluated stigma and beliefs about illness of 100 patients with schizophrenia and their caregivers, reported that stigma was related to specific beliefs about causes of mental illness; the total stigma score was associated with male gender. In our study, females scored significantly higher for the components of stereotype endorsement and total P-scale score and more of them experienced stigma (as assessed presence or absence of stigma based on total ISMIS after excluding the component of stigma resistance). In contrast, males scored significantly higher for the component of stigma resistance. Stigma being more common in females suggests that cultural factors play a role in the experience of self-stigma. Traditionally Indian society is considered to be male dominant. Even if males have deficits they are more often accepted and their retaliation is accepted, at least in the family context. In contrast, females are usually considered dependent on their male partners and are often ridiculed. Presence of mental illness increases the susceptibility in terms of subjective sense of deficiency/disability. Finding of higher stigma resistance in males can also be understood from the same cultural context, in which males with disability/mental illness are more often accepted in the family context and have all their rights, which is often not true for women with mental illness.

Many studies have reported the relationship of stigma and marriage related issues.[12] This is quite understandable in the context of Indian culture, in which marriage is almost universal phenomenon.

A study from Ranchi evaluated the relationship of stigma with insight in 100 patients with mental disorder, of whom 30 were diagnosed with schizophrenia and found that those with better insight perceived more stigma compared to those with poor insight.[13] However, our study failed to find any relationship between stigma and insight.

Raguram et al.[17] evaluated thirty patients with schizophrenia on Link's perceived stigma questionnaire and a short explanatory model interview for beliefs about the illness. Patients were likely to hide the history of schizophrenia and reported similar impact of the illness on their work, finances, and social interactions as reported by their caregivers. The findings on P-scale in our study can be considered to be similar to that of the previous study.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, our study suggests that patients with schizophrenia experience high level of stigma and this restricts many aspects of their lives. One factor that influences stigma is the level of functioning achieved with treatment; those patients who achieve higher level of functioning have lower experience of self-stigma, anticipated stigma, and also lower participatory restriction. The implication is for the clinicians to know the vicious cycle involving lower level of improvement and lower achievement of better functioning and higher perception of stigma. Other factors which influence alienation component of stigma include knowledge (or lack of) about their diagnosis and treatment. Accordingly, simple psychoeducation can help in reduction of alienation. Another important aspect which emerges from our study is the inverse relationship of being on paid job and experiencing of stigma. It is difficult to establish the cause-effect relationship here; however, this finding suggests that ensuring proper job to patients of schizophrenia can boost their self-esteem. Accordingly, there is a need to encourage politico-administrative policies to improve appropriate employment opportunities for patients with schizophrenia.

Limitations and future directions

Findings of our study must be interpreted in the light of its limitations. The study was limited to a single center. The study included patients in remission attending the outpatient services of a general hospital psychiatric unit. Accordingly, the findings of this study may not be generalized to those living in the community and not experiencing symptomatic remission. Our patients had long duration of illness; hence, the findings may not be generalized to those experiencing first episode of psychosis. Only few associations were noted between stigma and various sociodemographic and clinical variables. This could be because we selected only those patients who were regularly attending the psychiatric services and were in remission. It is possible that many of the patients who feel stigmatized could have actually dropped out of treatment and, hence, were not included in the study. Our study sample was also relatively small, and the patients were evaluated only once. We did not study the relationship of stigma with other factors such as hope, self-esteem, depression, demoralization, quality of life, coping, emotional distress, social functioning, social cognition, etc., which have been addressed by some of the studies.[10,46,51,52] Future studies should try to overcome these limitations by planning multicentric, larger sample size, and community-based patient populations, with focus on patients in different phases of illness.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Penguin Books; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott GC, Ziegler HL, Altman BM, Scott DR. Understanding stigma: Dimensions of deviance and coping. Deviant Behav. 1982;3:275–300. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corrigan PW, Rusch N. Mental illness stereotypes and service use: Do people avoid treatment because of stigma? Psychiatr Rehabil Skills. 2002;6:312–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verghese A, Baig A. Public attitudes towards mental illness: The Vellore study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1974;16:8–18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadri N, Sartorius N. The global fight against the stigma of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerlinger G, Hauser M, De Hert M, Lacluyse K, Wampers M, Correll CU. Personal stigma in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A systematic review of prevalence rates, correlates, impact and interventions. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:155–64. doi: 10.1002/wps.20040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van ’t Veer JT, Kraan HF, Drosseart SH, Modde JM. Determinants that shape public attitudes towards the mentally ill: A Dutch public study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:310–7. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jodi MG. Perceived stigma and depression among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:535–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Switaj P, Wciórka J, Smolarska-Switaj J, Grygiel P. Extent and predictors of stigma experienced by patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:513–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill K, Startup M. The relationship between internalized stigma, negative symptoms and social functioning in schizophrenia: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Psychiatry Res. 2013;206:151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shrivastava A, Johnston ME, Thakar M, Shrivastava S, Sarkhel G, Sunita I, et al. Origin and impact of stigma and discrimination in schizophrenia – Patients’ perception: Mumbai study. Stigma Res Action. 2011;1:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loganathan S, Murthy RS. Living with schizophrenia in India: Gender perspectives. Transcult Psychiatry. 2011;48:569–84. doi: 10.1177/1363461511418872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishra DK, Alreja S, Sengar KS, Singh AR. Insight and its relationship with stigma in psychiatric patients. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009;18:39–42. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.57858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loganathan S, Murthy SR. Experiences of stigma and discrimination endured by people suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:39–46. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charles H, Manoranjitham SD, Jacob KS. Stigma and explanatory models among people with schizophrenia and their relatives in Vellore, South India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2007;53:325–32. doi: 10.1177/0020764006074538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jadhav S, Littlewood R, Ryder AG, Chakraborty A, Jain S, Barua M. Stigmatization of severe mental illness in India: Against the simple industrialization hypothesis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:189–94. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raguram R, Raghu TM, Vounatsou P, Weiss MG. Schizophrenia and the cultural epidemiology of stigma in Bangalore, India. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:734–44. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000144692.24993.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thara R, Srinivasan TN. How stigmatising is schizophrenia in India? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46:135–41. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Jr, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR. Remission in schizophrenia: Proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:441–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2004;129:257–65. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss M. Explanatory model interview catalogue (EMIC): Framework for comparative study of illness. Transcult Psychiatry. 1997;34:235–63. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Brakel WH, Anderson AM, Mutatkar RK, Bakirtzief Z, Nicholls PG, Raju MS, et al. The participation scale: Measuring a key concept in public health. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:193–203. doi: 10.1080/09638280500192785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA. Scale to assess unawareness of mental disorder (SUMD) In: Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF, editors. Rating Scales in Mental Health. Hudson OH: Lexi-Comp; 2001. pp. 188–90. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotze C, King MP, Joubert PM. What do patients with psychotic and mood disorders know about their illness and medication? S Afr J Psychiatr. 2008;14:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramadan ES, El Dod WA. Relation between Insight and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia: Role of internalized stigma and depression. Curr Psychiatry. 2010;17:43–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sibitz I, Unger A, Woppmann A, Zidek T, Amering M. Stigma resistance in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:316–23. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosanya TJ, Adelufosi AO, Adebowale OT, Ogunwale A, Adebayo OK. Self-stigma, quality of life and schizophrenia: An outpatient clinic survey in Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60:377–86. doi: 10.1177/0020764013491738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghanean H, Nojomi M, Jacobsson L. Internalized stigma of mental illness in Tehran, Iran. Stigma Res Action. 2011;1:11–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Assefa D, Shibre T, Asher L, Fekadu A. Internalized stigma among patients with schizophrenia in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional facility-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:239. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rensen C, Bandyopadhyay S, Gopal PK, Van Brakel WH. Measuring leprosy-related stigma – A pilot study to validate a toolkit of instruments. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:711–9. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.506942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G. GAMIAN-Europe Study Group. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: The GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophr Res. 2010;122:232–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarisoy G, Kaçar ÖF, Pazvantoglu O, Korkmaz IZ, Öztürk A, Akkaya D, et al. Internalized stigma and intimate relations in bipolar and schizophrenic patients: A comparative study. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54:665–72. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Werner P, Aviv A, Barak Y. Self-stigma, self-esteem and age in persons with schizophrenia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20:174–87. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207005340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai YM, Hong CP, Chee CY. Stigma of mental illness. Singapore Med J. 2001;42:111–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Botha UA, Koen L, Niehaus DJ. Perceptions of a South African schizophrenia population with regards to community attitudes towards their illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:619–23. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lysaker PH, Tsai J, Yanos P, Roe D. Associations of multiple domains of self-esteem with four dimensions of stigma in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lysaker PH, Roe D, Yanos PT. Toward understanding the insight paradox: Internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:192–9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aryal S, Badhu A, Pandey S, Bhandari A, Khatiwoda P, Khatiwada P, et al. Stigma related to tuberculosis among patients attending DOTS clinics of Dharan municipality. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2012;10:48–52. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v10i1.6914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevelink SA, van Brakel WH, Augustine V. Stigma and social participation in Southern India: Differences and commonalities among persons affected by leprosy and persons living with HIV/AIDS. Psychol Health Med. 2011;16:695–707. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.555945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karidi MV, Stefanis CN, Theleritis C, Tzedaki M, Rabavilas AD, Stefanis NC. Perceived social stigma, self-concept, and self-stigmatization of patient with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pruß L, Wiedl KH, Waldorf M. Stigma as a predictor of insight in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schrank B, Amering M, Hay AG, Weber M, Sibitz I. Insight, positive and negative symptoms, hope, depression and self-stigma: A comprehensive model of mutual influences in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2014;23:271–9. doi: 10.1017/S2045796013000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hasson-Ohayon I, Ehrlich-Ben Or S, Vahab K, Amiaz R, Weiser M, Roe D. Insight into mental illness and self-stigma: The mediating role of shame proneness. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:802–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uchino T, Maeda M, Uchimura N. Psychoeducation may reduce self-stigma of people with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Kurume Med J. 2012;59:25–31. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.59.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murthy SR. Stigma of Mental Illness in the Third World. Geneva: World Psychiatric Association; 2005. Perspectives on the Stigma of Mental Illness. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sartorius N, Schulze H. Reducing the Stigma of Mental Illness. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park SG, Bennett ME, Couture SM, Blanchard JJ. Internalized stigma in schizophrenia: Relations with dysfunctional attitudes, symptoms, and quality of life. Psychiatry Res. 2013;205:43–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mashiach-Eizenberg M, Hasson-Ohayon I, Yanos PT, Lysaker PH, Roe D. Internalized stigma and quality of life among persons with severe mental illness: The mediating roles of self-esteem and hope. Psychiatry Res. 2013;208:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]