INTRODUCTION

The premenstrual syndrome is a common clinical condition; its prevalence depends on the threshold set for its identification. This article briefly describes its clinical features, examines issues related to its nomenclature and prevalence, considers controversies related to the diagnosis, and discusses its treatment. Special attention is paid to the use of sertraline as a treatment administered specifically within the window of symptom presence.

NOMENCLATURE

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) has had a checkered history in the psychiatric nomenclature. Commonly referred to in lay parlance as premenstrual tension, it has been known as the premenstrual syndrome, late luteal phase dysphoric disorder, and now, premenstrual tension syndrome (International Classification of Diseases-10th revision [ICD-10]) or PMDD (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition [DSM 5]). The current ICD-10 criteria are broad and easy to endorse;[1] as a result, the current ICD concept would include a substantial proportion of women during their reproductive lifespan. In contrast, the DSM criteria are narrow and specific;[1] as a result, the current DSM concept would identify only women at the severe end of the spectrum. As a striking example, in a sample of college students, the prevalence of the premenstrual syndrome was found to be 3.7% and 91.4%, depending on whether DSM or ICD criteria were applied.[2]

PREVALENCE

PMDD is a modestly common condition. The prevalence of PMDD is 3%–9%.[3] Similar numbers have been reported from India. In a small, early study of 62 women, Banerjee et al.[4] obtained a prevalence of 6.4% for PMDD in New Delhi. In a larger, more recent study, Raval et al.[2] identified a prevalence of 3.7% in a sample of 489 college girls in Bhavnagar, Gujarat. Mishra et al.[5] obtained a prevalence of 37% in 100 female medical students residing in hostel facilities in Ahmedabad, Gujarat; this outlying finding may have resulted from the special nature of the sample, selection bias (symptom-free girls not returning the questionnaire), and other methodological issues. Other figures obtained were 4.7% in a sample of 1355 adolescent girls in Anand, Gujarat,[6] 12.2% in a sample of 221 high school girls in Ahmedabad,[7] and 10% in a sample of nursing staff and students in Wardha, Maharashtra.[8]

CLINICAL FEATURES

PMDD comprises mood symptoms such as anxiety, depression, irritability, anger, or affective lability; physical symptoms such as bloating or muscle pain; and other symptoms, such as poor concentration, decreased interests, lethargy, and changes in sleep and appetite. The symptoms require to be present across several menstrual cycles, appear in the week before the onset of a menstrual period, and diminish and disappear shortly after the onset of the period. To merit diagnostic status, the symptoms need to cause significant distress or impairment in work, social, or interpersonal spheres of functioning.[9]

CONTROVERSIES

PMDD has for long been a controversial diagnosis. It has been considered to stigmatize or marginalize women, to comprise an attempt by the pharmaceutical industry, to medicalize a normal experience, and to represent a culture-specific syndrome rather than a universally prevalent condition. These and other concerns about the research on PMDD were addressed in a detailed review by Hartlage et al.;[10] the authors concluded that PMDD is a global disorder that merits full diagnostic attention.

TREATMENT

A large number of treatments have been trialed for PMDD. These include hormonal treatments, psychological treatments (from stress management to formal psychotherapy), physical treatments (e.g. yoga, aerobic exercise), mineral supplements (e.g. calcium), nutritional supplements (e.g. vitamins, omega-3 fatty acids), herbal supplements (e.g. Ginkgo biloba, Crocus sativus), and last but not least, antidepressant drugs (ADs).[9] Other interventions have included salt restriction, caffeine restriction, diuretic agents, and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Among the ADs, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been the best investigated, historically starting with fluoxetine.[11,12] In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 31 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of an SSRI for premenstrual syndrome disorders, Marjoribanks et al.[13] obtained small-to-medium effect sizes for self-reported improvement, depending on the nature of the end point studied.

In the initial RCTs, ADs were dosed throughout the menstrual cycle.[11,12] However, it quickly became apparent that it might be sufficient to treat affected women during the luteal phase alone. For example, in an small, early RCT, Halbreich and Smoller[14] found that benefits with luteal phase dosing with sertraline were similar to those with continuous dosing. Meta-analysis has now confirmed that SSRIs are superior to placebo whether administered only during the luteal phase or all through the menstrual cycle; whether the two treatment strategies are comparable in efficacy is however unclear.[13]

TARGETED, SYMPTOM-ONSET TREATMENT

SSRI treatment of the premenstrual syndrome is associated with a dose-dependent adverse effect burden that includes nausea (NNH, 7), decreased energy (NNH, 9), somnolence (NNH, 13), fatigue (NNH, 14), decreased libido (NNH, 14), and sweating (NNH, 14); there is also a more than doubled risk of drug discontinuation symptoms.[13] The symptoms of PMDD typically begin 4–7 days before the onset of a menstrual period and end shortly after the onset of menstruation. Therefore, taking medication during the entire menstrual cycle would expose the woman to possible medication adverse effects at times that the treatment is not required, besides adding to the treatment cost. A similar argument can be adduced for treating women during the late luteal phase; there may be several unnecessary days of treatment.

It is generally assumed that ADs take time for onset of action, regardless of indication. What if, instead, ADs can be used symptomatically for immediate relief, much as, for example, paracetamol is used to treat fever or pain? This unusual idea was explored in the context of PDD treatment by several authors, with generally favorable findings, starting as far back as in 2005.[15,16,17,18,19]

TARGETED, SYMPTOM-ONSET TREATMENT WITH SERTRALINE: RECENT RESEARCH

In the most recent study, Yonkers et al.[20] described a large (n = 252), industry-independent, three-center RCT of sertraline (n = 125) versus placebo (n = 127) in women with prospectively confirmed PMDD. No woman had significant medical or psychiatric comorbidities. The mean age of the women was about 34 years. The sample was about 70% white. Sertraline was flexibly dosed at 50–100 mg/day, starting at the time of PMDD symptom onset and uptitrating or downtitrating to the ideal dose; treatment was abruptly discontinued after the first few days of menstruation. Each woman was treated in this manner for six menstrual cycles.

There were 37 dropouts from the sertraline group and 39 from the placebo group; reasons for dropout were closely similar in the two groups except that fewer sertraline women dropped out because they required rescue therapy relative to placebo women (3 vs. 9, respectively).

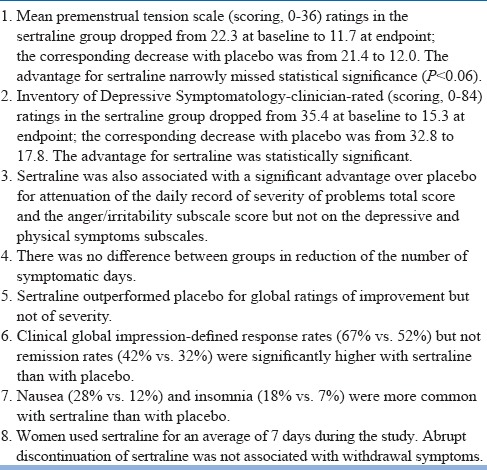

Important findings from the study are presented in Table 1. In summary, symptom-onset treatment with sertraline (50–100 mg/day for about 7 days) was associated with a significant reduction in women's daily record of problem severity (including, specifically, on the anger/irritability subscale), with a significant reduction in depression ratings, and a near-significant reduction in premenstrual tension ratings. Response but not remission rates were significantly higher with sertraline. Discontinuation of sertraline after the onset of menstruation did not result in drug discontinuation symptoms. The large sample size (n = 252) and long study duration (six menstrual cycles) were important strengths of this study.

Table 1.

Important findings from Yonkers et al.[20]

DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Some questions remain to be addressed in future research. One is whether targeted, symptom-onset treatment is as effective as (and better tolerated than) treatment during the late luteal phase and treatment during the entire menstrual cycle. Another is the strategy to be adopted in women who fail to respond to targeted, symptom-onset sertraline in the dose employed by Yonkers et al.;[20] should a higher dose be employed, should a different drug be trialed, or should women be advised treatment during the luteal phase or even during the entire menstrual cycle?

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freeman EW. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Definitions and diagnosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(Suppl 3):25–37. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raval CM, Panchal BN, Tiwari DS, Vala AU, Bhatt RB. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder among college students of Bhavnagar, Gujarat. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:164–70. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.183796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson LL, Ismail KM. Clinical epidemiology of premenstrual disorder: Informing optimized patient outcomes. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:811–8. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S48426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee N, Roy KK, Takkar D. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder – A study from India. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2000;45:342–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra A, Banwari G, Yadav P. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder in medical students residing in hostel and its association with lifestyle factors. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015;24:150–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.181718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamat SV, Nimbalkar AS, Nimbalkar SM. Premenstrual syndrome in adolescents of anand – Cross-sectional study from India using premenstrual symptoms screening tool for adolescents (PSST-A) Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:A136. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parikh MN, Parikh NC, Parikh SK. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder in adolescent girls in Western India. Gujarat Med J. 2015;70:65–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padhy SK, Sarkar S, Beherre PB, Rathi R, Panigrahi M, Patil PS. Relationship of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder with major depression: Relevance to clinical practice. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37:159–64. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.155614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Epidemiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17:87. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0628-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartlage SA, Breaux CA, Yonkers KA. Addressing concerns about the inclusion of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in DSM-5. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:70–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13cs08368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone AB, Pearlstein TB, Brown WA. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990;26:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone AB, Pearlstein TB, Brown WA. Fluoxetine in the treatment of late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:290–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marjoribanks J, Brown J, O’Brien PM, Wyatt K. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD001396. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halbreich U, Smoller JW. Intermittent luteal phase sertraline treatment of dysphoric premenstrual syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:399–402. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman EW, Sondheimer SJ, Sammel MD, Ferdousi T, Lin H. A preliminary study of luteal phase versus symptom-onset dosing with escitalopram for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:769–73. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kornstein SG, Pearlstein TB, Fayyad R, Farfel GM, Gillespie JA. Low-dose sertraline in the treatment of moderate-to-severe premenstrual syndrome: Efficacy of 3 dosing strategies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1624–32. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yonkers KA, Holthausen GA, Poschman K, Howell HB. Symptom-onset treatment for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:198–202. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000203197.03829.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravindran LN, Woods SA, Steiner M, Ravindran AV. Symptom-onset dosing with citalopram in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD): A case series. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10:125–7. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landén M, Erlandsson H, Bengtsson F, Andersch B, Eriksson E. Short onset of action of a serotonin reuptake inhibitor when used to reduce premenstrual irritability. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:585–92. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yonkers KA, Kornstein SG, Gueorguieva R, Merry B, Van Steenburgh K, Altemus M. Symptom-onset dosing of sertraline for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1037–44. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]