Abstract

Background

Recent reviews have synthesised the psychometric properties of measures developed to examine implementation science constructs in healthcare and mental health settings. However, no reviews have focussed primarily on the properties of measures developed to assess innovations in public health and community settings. This review identified quantitative measures developed in public health and community settings, examined their psychometric properties, and described how the domains of each measure align with the five domains and 37 constructs of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).

Methods

MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and CINAHL were searched to identify publications describing the development of measures to assess implementation science constructs in public health and community settings. The psychometric properties of each measure were assessed against recommended criteria for validity (face/content, construct, criterion), reliability (internal consistency, test-retest), responsiveness, acceptability, feasibility, and revalidation and cross-cultural adaptation. Relevant domains were mapped against implementation constructs defined by the CFIR.

Results

Fifty-one measures met the inclusion criteria. The majority of these were developed in schools, universities, or colleges and other workplaces or organisations. Overall, most measures did not adequately assess or report psychometric properties. Forty-six percent of measures using exploratory factor analysis reported >50 % of variance was explained by the final model; none of the measures assessed using confirmatory factor analysis reported root mean square error of approximation (<0.06) or comparative fit index (>0.95). Fifty percent of measures reported Cronbach’s alpha of <0.70 for at least one domain; 6 % adequately assessed test-retest reliability; 16 % of measures adequately assessed criterion validity (i.e. known-groups); 2 % adequately assessed convergent validity (r > 0.40). Twenty-five percent of measures reported revalidation or cross-cultural validation. The CFIR constructs most frequently assessed by the included measures were relative advantage, available resources, knowledge and beliefs, complexity, implementation climate, and other personal resources (assessed by more than ten measures). Five CFIR constructs were not addressed by any measure.

Conclusions

This review highlights gaps in the range of implementation constructs that are assessed by existing measures developed for use in public health and community settings. Moreover, measures with robust psychometric properties are lacking. Without rigorous tools, the factors associated with the successful implementation of innovations in these settings will remain unknown

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13012-016-0512-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Public health, Implementation research, Psychometric, Measure, Factor analysis

Background

In the field of implementation science, a considerable number of theories and frameworks are being used to better understand implementation processes and guide the development of strategies to improve the implementation of health innovations [1–3]. Many of these theories and frameworks, however, have not been tested empirically. As such, examining the utility of theories and frameworks has been recognised as critical to advance the field of implementation science [4].

The assessment of implementation theories and frameworks necessitates robust measures of their theoretical constructs. Psychometric properties important for measures of implementation research have been proposed [5] and include the following: reliability (internal consistency and test-retest); validity (construct and criterion); broad application (validated in different settings and cultures); and sensitivity to change (responsiveness). Tools which are acceptable, feasible, and display face and content validity are also particularly useful for researchers in real-world settings [5]. Furthermore, the psychometric characteristics of measures that assess a comprehensive range of implementation constructs have been highlighted as a particular priority area of research [4].

A number of reviews of implementation measures exist [6–13]. Such reviews indicate that the quality of existing measures of implementation constructs is limited. A review by Brennan and colleagues, for example, identified 41 instruments designed to assess factors hypothesised to influence quality improvement in primary care [6]. The review found that while most studies reported the internal consistency of instruments, very few assessed the construct validity of the measures using factor analysis [6]. Similarly, in a review of the psychometric properties of research utilisation measures used in health care, Squires and colleagues found that, of the 97 identified studies (60 unique measures), only 31 reported internal consistency and only 3 reported test-retest reliability [13]. Twenty percent of the included measures had not undergone any type of validity testing, and no studies reported on measure acceptability [13].

There are a number of limitations of previous reviews. Most do not provide comprehensive details of the psychometric properties of included measures [7, 8, 12] or address only a small number of constructs or outcomes relevant to implementation science [8, 10]. Additionally, the majority of these reviews primarily focus on measures developed for use in healthcare settings [6, 9, 11, 13]. Evidence from the field of psychometric research has suggested that, even when administered to similar population groups, changes in measure reliability and validity can occur when a measure developed in one setting is applied to another setting with different characteristics [14, 15].

Currently, a comprehensive review of measures of implementation constructs is being conducted by the Society for Implementation Research Collaboration (SIRC) Instrument Review Project [16, 17]. The SIRC review addresses some of the limitations of past reviews by extracting a range of psychometric properties from identified measures and assessing a more comprehensive range of outcomes [18] and constructs relevant to implementation science [19]. The outcomes of interest in the SIRC review are taken from Proctor and colleagues’ Implementation Outcomes Framework (IOF) and focus on the appropriateness, acceptability, feasibility, adoption, penetration, cost, fidelity, and sustainability of the intervention itself [18]. The constructs of interest for the review are drawn from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), which outlines factors or conditions deemed important to support the successful implementation of an intervention [19]. The constructs are grouped under five domains which describe the following: (1) Intervention characteristics (details of the intervention itself); (2) Outer setting (factors of influence which are external to an organisation); (3) Inner setting (internal characteristics of an organisation such as culture and learning climate); (4) Characteristics of individuals (actions and behaviours of individuals within the organisation); and (5) Process (systems and pathways within an organisation) [19].

To date, the SIRC review has uncovered 420 instruments related to 34 of the CFIR constructs and 104 instruments related to Proctor and colleagues’ IOF [16, 17]. At present, the data are available for the measures relevant to the inner setting domain of the CFIR and the IOF [20]. However, while comprehensive, the SIRC review only pertains to measures primarily applied to healthcare or mental health care settings, where the individuals responsible for implementing health-related interventions are most likely to be healthcare professionals [16, 17]. In the field of public health, the implementation of health-related interventions often occurs in non-clinical settings, with non-healthcare professionals responsible for implementing these changes. Therefore, there is a need to identify measures which have been developed specifically to measure constructs important for the implementation of health-related interventions in community settings, where the primary role of the organisations and individuals is not healthcare delivery.

To our knowledge, no previous reviews of measures of implementation constructs have focussed on instruments designed for use in a broad range of community settings. Such measures are of particular interest to public health researchers who are utilising implementation theories or frameworks to support evidence-based practice in these settings. As such, the aim of this study was to (1) systematically review the literature to identify measures of implementation constructs which have been developed in community settings; (2) describe each measure’s psychometric properties; and (3) describe how the domains of each measure align with the five domains and 37 constructs of the CFIR.

Methods

Scope of this review

The focus of this review was to identify, from peer-reviewed literature, measures which have been developed for use in community-based (non-clinical settings), and which measure constructs aligned to the CFIR. These measures were then examined to determine their psychometric properties and identify which of the CFIR constructs they captured. In this review, ‘measures’ are defined as surveys, questionnaires, instruments, tools, or scales which contain individual items that are answered or scored using predefined response options. ‘Constructs’ are defined as the broad attributes or characteristics which these items (usually grouped into domains) are attempting to capture. The constructs of interest were chosen to align with the CFIR, as this framework is the most comprehensive and draws together numerous theories which have been developed to guide the planning and evaluation of implementation research and combines them into one uniform theory with overarching domains [19].

Design

A systematic search and review was conducted to address the broad question of ‘what psychometrically robust measures are currently available to assess implementation research in public health and community settings’. A comprehensive search of peer-reviewed publications was conducted using four electronic databases and the quality of identified measures was assessed using well-established, pre-defined psychometric criteria.

Eligibility

Publications were included if they (1) were peer-reviewed journal articles reporting original research results; (2) reported research from non-clinical settings; (3) reported details regarding the development of a measure; (4) described a measure which assessed at least one of the 37 CFIR constructs; (5) described a measure which was being applied to a specific innovation or intervention; and (6) used statistical methods to assess the measures’ factor structure.

In this review, clinical settings included the following: hospitals, general practices, allied health facilities such as physiotherapy or dental practices, rehabilitation centres, psychiatric facilities, and any other settings where the delivery of health or mental health care was the primary focus. Non-clinical settings included schools, universities, private businesses, childcare centres, correctional facilities, and any other settings where the delivery of health or mental health care was not the primary focus. Given that an aim of the study was to map the domains of included measures against constructs within the CFIR, it was important that measures displayed a minimum level of construct validity via exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis.

Duplicate abstracts were excluded from the review, as were abstracts describing reviews, editorials, commentaries, protocols, conference abstracts, and dissertations. Publications which reported on measures developed using qualitative methods only were also ineligible.

Search strategy

A search of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and CINAHL databases was conducted to identify publications describing the development of measures to assess factors relevant to the implementation of innovations. These four databases were selected as they index journals from the field of implementation science and provide extensive coverage of research across a range of public health and community settings, such as schools, pharmacies, businesses, nursing homes, sporting clubs, and childcare facilities.

Prior to the database searches being conducted, four authors met to ensure that the chosen keywords accurately captured the constructs of interest and that keywords were combined using the correct Boolean operators [21]. The core search terms comprised of keywords that related to measurement, the psychometric properties of instruments, the levels at which the measurement could occur (e.g. organisational or individual) and the goals of research implementation. These keywords were as follows: [questionnaire or measure or scale or tool] AND [psychometric or reliability or validity or acceptability] AND [organisation* or institut* or service or staff or personnel] AND [implement* or change or adopt* or sustain*].

Similar to the strategy used in the SIRC review [16, 17], the core search terms were combined with five more keyword searches designed to capture the constructs within each of the five CFIR domains: (1) Intervention Characteristics [strength or quality or advantage or adapt* or complex* or pack* or cost]; (2) Outer Setting [needs or barrier* or facilitate* or resource* or network or external or peer or compet* or poli* or regulation* or guideline* or incentive*]; (3) Inner Setting [structur* or communication or cultur* or value* or climate or tension or risk* or reward* or goal* or feedback or commitment or leadership or knowledge*]; (4) Characteristics of Individuals [belief* or attitude* or self-efficacy or skill* or identi* or trait* or ability* or motivat*]; or (5) Process [plan* or market or train or manager or team or champion or execut* or evaluat*].

The keyword search terms were repeated for all four databases. Keyword searches were limited to the English language; however, no limit was placed on the year of publication, as measurement tools often evolve over many years. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were not used in the literature search, as keyword searches have been found to have higher sensitivity, being more successful than subject searching in identifying relevant publications [22].

Identification of eligible publications

One author coded all abstracts according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A second author cross-checked 10 % of the abstracts to confirm they had been correctly classified. Full-text versions of publications were obtained for included abstracts. To ensure that no relevant tools had been missed, previous systematic reviews [7, 8, 10] were also screened for relevant measures, as were tools included on the SIRC Instrument Review Project website [20]. Copies of publications for any additional measures that met the inclusion criteria were obtained. Full-text versions of all eligible publications were then obtained and screened to identify the names and acronyms of all relevant measures they described. The reference lists of all eligible publications were also screened for any additional measures, and Google Scholar was used to conduct cited reference searches. A final literature search was conducted by ‘measure name’ and ‘author names’, using Google Scholar. This search strategy ensured that as many publications as possible were found that related to the psychometric development and validation and revalidation and cross-cultural adaptation of identified measures.

Extraction of data from eligible publications

The properties of each measure were extracted from all full-text publications relating to the development of the measure using data reported in the manuscript text, tables, or figures. Extracted data included: (1) the research setting, sample, and characteristics of the intervention or innovation being assessed; (2) psychometric properties including face and content validity, construct and criterion validity, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, responsiveness, acceptability, and feasibility; and (3) whether the measure had undergone a process of revalidation or cross-cultural adaptation.

The psychometric properties of each measure were independently assessed by two authors using the same criteria described in previous systematic reviews [23, 24] and according to the guidelines for the development and use of tests, including the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing [5, 25, 26]. The Standards provides a frame of reference to ensure all relevant issues are addressed when developing a measure and allows the quality of measures to be evaluated by those who wish to use them [25]. Following the assessment of psychometric properties, two authors then independently coded each publication to determine which measure domains corresponded with which CFIR constructs. When discrepancies emerged, a third author assisted in reaching consensus.

Psychometric coding

Setting, sample, and characteristics of the innovation being assessed

Details regarding the country and setting where the measure was developed, characteristics of the innovation or intervention being assessed, response rate, sample size, and demographic characteristics of the sample (gender and profession) who completed the measure were described.

Face and content validity

An instrument is said to have face validity if both the administrators and those who complete it agree that it measures what it was designed to measure [27]. To have content validity, the description of the measure’s development needed to include: (1) the process by which items were selected; (2) who assessed the measure’s content; and (3) what aspects of the measure were revised [14, 28]. Information regarding any theories or frameworks that the measure was developed to test, as well as whether items were adapted from previously validated measures, was also extracted.

Construct and criterion validity

A measure was classified as having good internal structure (construct validity) if exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed with eigenvalues set at >1 [14, 29] and >50 % of the variance was explained [30], or confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed with a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of <0.06 and a comparative fit index (CFI) of >0.95 [31, 32]. The number of items and domains in the measure following factor analysis was recorded. Additional construct validity was determined by assessing whether the measure had convergent validity (correlations (r) >0.40) with similar instruments or divergent validity (correlations (r) <0.30) with dissimilar instruments [33]. Criterion validity was determined by assessing whether the measure was able to obtain different scores for sub-populations with known differences (known-groups validity) [34].

Internal consistency and test-retest reliability

To meet the criteria for internal consistency, correlations for a measure’s subscales and total scale needed to have a Cronbach’s alpha (α) of >0.70 or a Kuder-Richardson 20 (KR-20) of >0.70 for dichotomous response scales [28]. For test-retest reliability, the measure needed to have undergone a repeated administration with the same sample within 2–14 days [35]. Agreement between scores from the two administrations needed to be calculated, with item, subscale, and total scale correlations having a (1) Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ) of >0.60 for nominal or ordinal response scales [14]; (2) Pearson correlation coefficient (r) of >0.70 for interval response scales [14, 28]; or an (3) Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of >0.70 for interval response scales [14, 28].

Responsiveness, acceptability, feasibility, revalidation, and cross-cultural adaptation

A measure’s potential to detect change over time was confirmed if it could show a moderate effect size (>0.5) for a given change [14, 28, 36], and if it had minimal floor and ceiling effects (less than 5 % of the sample achieved the highest or lowest scores) [37]. To determine acceptability and feasibility (burden associated with using the measure), data on the following were extracted: proportion of missing items, time needed to complete, and time needed to interpret and score [28]. Data from publications reporting the revalidation of a measure with additional samples, or in different languages or cultures, were also extracted [28].

CFIR coding

The domains of each included measure were assessed to determine whether the factors they measured corresponded with one or more of the 37 CFIR constructs [19]. A brief summary of each of the CFIR constructs is presented in Additional file 1. The mapping process was domain-focused (i.e. mapping the overall measure domains to constructs) rather than item-focused (i.e. mapping individual items to constructs) to ensure that the overall construct was well captured. Within a measure, only one domain needed to be judged by the reviewers to address a CFIR construct. Therefore, it was possible that a measure with five domains might only have one of its domains mapped to a CFIR construct. Similarly, a measure with three domains might have all contributing to the same CFIR construct. In the latter scenario, the construct was only counted once.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies and proportions) were used to report the number of domains from the included measures which were mapped to each of the CFIR constructs and CFIR domains. Frequencies and proportions were also used to describe the number of measures which met various psychometric criteria.

Results

Identified measures of implementation constructs

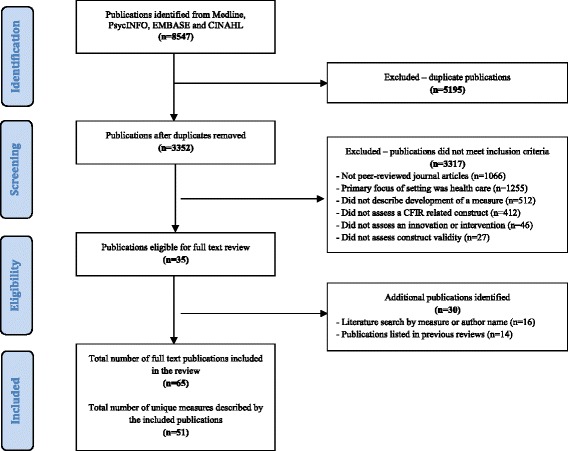

The initial searches of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and CINAHL identified 8547 potentially relevant publications. Of these, 5195 were duplicates leaving 3352 publication abstracts to be coded. Of these 3352 publications, 3317 did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1 for PRISMA diagram), leaving 35 eligible publications. The process of identifying measures included in systematic reviews related to the current review [7, 8, 10], and a secondary literature search by measure or author name, lead to the inclusion of an additional 30 publications. A total of 65 full-text publications were retained which described 51 unique measures.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the publication and measure inclusion process

Psychometric properties of measures

Setting, sample, and characteristics of the innovation being assessed

Table 1 outlines the details of the setting, sample, and characteristics of the innovation being assessed by each measure. The majority of measures were developed in the USA (n = 28), with Canada and Australia also having developed three or more measures each. Sixteen measures were developed for use in school settings [38–52], six for use in universities or colleges [53–60], three for use in pharmacies [61–63], two for use in police or correctional facilities [64, 65], two for use in nursing homes [66, 67], six for use with whole communities or in multiple settings [68–75], and sixteen measures were developed for use in workplace settings or other organisations (e.g. utility companies, IT service providers, human services) [76–92]. A broad range of innovations or interventions were assessed, with technology-focussed innovations featuring prominently. Sample sizes in each study ranged from 31 to 1358, and response rates ranged from 15 to 98 %. Sample characteristics (i.e. gender and profession of participants) were inconsistently reported across the studies.

Table 1.

Setting, sample, and characteristics of the innovation being assessed

| Measure | Country | Setting | Characteristics of the innovation being assessed | Sample size | Response rate | Gender and profession of participants (Standard 1.8)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schools | ||||||

| Adopter Characteristics Scale [43] | USA | Schools in Texas (number not reported) | Adoption and use of a classroom educational programme for tobacco prevention | n = 131 | 54 % | Second grade teachers |

| Awareness and Concern Instrument [51] | USA | School districts in North Carolina with at least two junior high or middle schools (n = 21) | Awareness, concern, and interest in adopting and implementing tobacco prevention the curricula | n = 917 | Not reported | Central office administrators Principals Teachers |

| Health Teaching Self-Efficacy (HTSE) Scale [47] | USA | Schools in the Region IV district of the Texas Education Agency (number not reported) | Ability to implement health teaching in the classroom | n = 31 | Not reported | Junior high teachers Senior high teachers |

| Index of Inter-professional Team Collaboration-Expanded School Mental Health (IITC-ESMH) [50] | USA | Schools across the USA (number not reported) | Level of inter-professional collaboration occurring to implement learning support and mental health promotion strategies in schools | n = 436 | Not reported | Female = 88 % School-employed mental health workers (e.g. school counsellors) Community-based mental health workers (e.g. clinical psychologists) School nurses Educators |

| McKinney-Vento Act Implementation Scale (MVAIS) [40] | USA | Illinois Association of School Social Workers annual conference | Perceived knowledge and awareness regarding implementation of the McKinney-Vento Act | n = 201 | 40 % | Female = 92 % School social workers |

| Organisational Climate Instrument [51] | USA | School districts in North Carolina with at least two junior high or middle schools (n = 21) | Perceptions regarding the organisational climate in schools adopting tobacco prevention curricula | n = 910 | Not reported | Central office administrators Principals Teachers |

| Perceived Attributes of the Healthy Schools Approach Scale [42] | Canada | Schools in Quebec (n = 107) | Perceived attributes of a health promoting school initiative | n = 141 | 28 % | Female = 62 % Principals School health promotion delegates |

| Policy Characteristics Scale [52] | Belgium | Flemish secondary schools, including community schools, and subsidised public and private schools (n = 37) | Perceptions of a new teacher evaluation policy | n = 347 | 82 % | Female = 58 % Teachers |

| Role-Efficacy Belief Instrument (REBI) [45] | USA | Schools in a state recently mandating sexuality education (number not reported) | Role-efficacy related to the successful implementation of a mandated sexuality curriculum | n = 123 | Not reported | Female = 67 % County-level curriculum coordinators |

| Rogers’s Adoption Questionnaire [51] | USA | School districts in North Carolina with at least two junior high or middle schools (n = 21) | Perceptions regarding the characteristics of three different tobacco prevention curricula | n = 251 | Not reported | Central office administrators Teachers |

| School Wellness Policy Instrument (WPI) [48] | USA | Public elementary schools in Mississippi (n = 30) | Acceptance and implementation of nutrition competencies as part of a school wellness policy | n = 947 | 34 % | Teachers |

| School-level Environment Questionnaire—South Africa (SLEQ-SA) [38] | South Africa | Secondary schools in the Limpopo Province (n = 54) | Perceptions of the school-level environment with regard to the implementation of outcomes-based education | n = 403 | Not reported | Teachers |

| School Success Profile—Learning Organisation (SSP-LO) Measure [39] | USA | Public middle schools in North Carolina (n = 11) | Perceptions of organisational learning as part of an evaluation of the effectiveness and sustainability of the School Success Profile Intervention Package | n = 766 | 80 % | Teachers Specialists Teacher assistants Administrators Other employees (e.g. cafeteria workers) |

| School Readiness for Reforms—Leader Questionnaire (SRR-LQ) [41] | USA | Elementary, middle, and high schools in nine districts from South-west Florida (n = 169) | Perceptions regarding school readiness for the implementation of reforms including standards-based testing | n = 167 | 99 % | Leaders from elementary schools (e.g. principals, assistant principals, curriculum specialists) Leaders from high schools Leaders from middle schools |

| School-wide Universal Behaviour Sustainability Index—School Teams (SUBSIST) [46, 49] | USA | Elementary, middle, and secondary public schools in Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, and Oregon who were implementing school-wide positive behaviour support (n = 14) | Evaluation of school capacity to sustain school-wide positive behaviour support | n = 25 | Not reported | Internal school team leaders External district coaches |

| Teacher Receptivity Measure [44] | USA | Elementary schools in Texas (number not reported) | Views towards the implementation of the smoke-free class of 2000 teaching kit | n = 216 | 79 % | First grade teachers |

| Universities/colleges | ||||||

| Intention to Adopt Mobile Commerce Questionnaire [54, 55] | Kazakhstan | Private institutions of higher learning in Almaty and Astana (n = 3) | Intention to adopt mobile commerce | n = 345 | 51 % | Female = 50 % University students |

| Perceived Attributes of eHealth Innovations Questionnaire [53] | USA | Education providers including community colleges, state colleges and universities from across the United States (n = 12) | Perceived attributes of a technological innovation for health education | n = 193 | 84 % | Male = 53 % Sophomores Freshman Juniors Seniors |

| Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use Scale [56] | USA | Business school at Boston University | Evaluation of usefulness and ease of use of two computer programmes | n = 40 | 93 % | MBA students |

| Post-adoption Information Systems Usage Measure [59] | USA | University in the United States | Post-adoption perceptions of a self-service, web-based student information system | n = 1008 | Not reported | Females = 53 % University students |

| Social Influence on Innovation Adoption Scale [60] | Australia | University of South Australia | Attitudes towards adopting advanced features of email software | n = 275 | 15 % | Female = 64 % Academic staff Professional staff |

| Tertiary Students Readiness for Online Learning (TSROL) Scale [57, 58] | Australia | Metropolitan university in Australia | Readiness to adopt an online approach to teaching and learning | n = 254 | 52 % | Female = 65 % University students |

| Pharmacies | ||||||

| Facilitators of Practice Change Scale [63] | Australia | Australian community pharmacies (n = 735) | Facilitators of practice change with regard to the implementation of cognitive pharmaceutical services in community pharmacies | n = 1303 | Not reported | Proprietor pharmacists Employee pharmacists Pharmacy assistants (including technicians) |

| Leeds Attitude Towards Concordance (LATCon) Scale [62] | Finland | Finnish community pharmacies (number not reported) | Attitudes towards the implementation of a new counselling model based on concordance and mutual decision-making between pharmacists and patients | n = 376 | 51 % | Community pharmacists |

| Perceived Barriers to the Provision of Pharmaceutical Care Questionnaire [61] | China | Community pharmacies in Xian, China (number not reported) | Attitudes and barriers to the implementation of pharmaceutical care | n = 101 | 78 % | Female = 82 % Prescription checking staff Quality assurance staff Staff managers |

| Police/correctional facilities | ||||||

| Perceptions of Organisational Readiness for Change [65] | USA | Juvenile justice offices (n = 12) | Perceptions of organisational readiness to implement an innovation consisting of screening, assessment, and referral strategies | n = 231 | Not reported | Female = 58 % Case-workers Managers Front-line supervisors |

| Receptivity to Organisational Change Questionnaire [64] | USA | Districts I and II of the Hillsborough County, Florida Sheriff’s Office (n = 2) | Attitudes regarding an agency-wide shift towards community-oriented policing | n = 204 | 98 % | Patrol deputies Other sworn employees |

| Nursing homes | ||||||

| Intervention Process Measure (IPM) [67] | Denmark | Elderly care centres (n = 2) | Assessment of employee perceptions related to the implementation of self-managed teams | n = 163 | 81 % | Female = 93 % Healthcare assistants Nurses Other health educated staff Staff with no healthcare education |

| Staff Attitudes to Nutritional Nursing (SANN) Care Scale [66] | Sweden | Residential units in a municipality of southern Sweden (n = 8) | Attitudes of nursing staff towards the implementation of nutritional nursing care | n = 176 | 95 % | Registered nurses Nurse aids |

| Whole communities/multiple settings | ||||||

| 4-E Telemeter [70, 71] | Netherlands | Education-related settings from 39 countries including elementary, secondary, university, vocational, and company training settings (number not reported) | Likelihood of using telecommunications-related technological innovations in learning-related settings | n = 550 | Not reported | Instructors Students Administrators Educational support unit members Technical support unit members Researchers |

| Attitudes Towards Asthma Care Mobile Service Adoption Scale [94] | Taiwan | General community | Attitudes and behavioura towards the adoption of a asthma care mobile service | n = 229 | 57 % | Male = 63 % |

| Intention to Adopt Multimedia Messaging Service Scale [69] | Taiwan | General community | Attitudes towards and intention to adopt multimedia messaging services | n = 112 | Not reported | Male = 55 % Students Electronics or IT sector employees Education sector employees Financial services, entertainment, media, government, health care, and law office employees |

| Systems of Care Implementation Survey (SOCIS) [68, 72] | USA | Education settings, mental health services, family assistance organisations, child welfare services, juvenile justice services and medical services from 225 counties across the USA (number not reported) | Level of implementation of factors contributing to effective children’s systems of care | n = 910 | 42 % | Female = 72 % |

| Stages of Concern Questionnaire (SoCQ) [73, 74] | USA | Elementary schools and higher education institutions in the USA (number not reported) | Concerns about innovations including team teaching in elementary schools and using instructional modules in colleges | n = 830 | Not reported | Public school teachers College professors Specialists Teacher assistants Administrators Other employees (e.g. cafeteria workers) |

| Telepsychotherapy Acceptance Questionnaire [75] | Canada | First nations communities in Quebec (n = 32) | Attitudes and perceptions of adoption and referral to telepsychotherapy delivered via videoconference | n = 205 | 77 % | Female = 70 % Community elders/natural helpers Social assistants/social workers Nurses/school nurses Psychoeducators Educators/teachers Psychologists Social interveners Community health representatives Non-professionals |

| Other workplaces/organisations | ||||||

| Adoption of Customer Relationship Management Technology Scale [88] | USA | A national buying cooperative for hardware and variety businesses in the USA | Facilitators to adopting customer relationship management technology | n = 386 | 48 % | Owner-operators of hardware and variety businesses |

| Coping with Organisational Change Scale [83] | USA | International organisations including Australian banks, a Scandinavian shipping company, a United Kingdom oil company, a US university and a Korean manufacturing company (n = 6) | Ability to cope with organisational change including reorganisation and downsizing, managerial changes, mergers and acquisitions, and business divestments | n = 514 | 71 % | Male = 91 % Middle and upper-level managers |

| Data Mining Readiness Index (DMRI) [80] | Malaysia | Telecommunication organisations (number not reported) | Readiness to adopt data mining technologies | n = 106 | 43 % | Telecommunications employees |

| Group Innovation Inventory (GII) [78, 91] | USA | High-technology companies, primarily in the aerospace and electronics industries (number not reported) | Attitudes towards innovation within groups developing new component-testing programmes, systems-level integration projects, engineering audit procedures, and failure analyses | n = 244 | Not reported | Managers/supervisors Engineers/scientists |

| Intention to Adopt Electronic Data Interchange Questionnaire [79] | Canada | Purchasing Managers’ Association of Canada (PMAC) | Intention to adopt electronic data interchange | n = 337 | 58 % | Senior purchasing managers |

| Organisational Change Questionnaire-Climate of Change, Processes, and Readiness (OCQ-C, P, R) [77] | Belgium | Belgian organisations from sectors including information technology, petrochemicals, telecommunications, consumer products, finance, insurance, consultancy, healthcare, and government services (n = 42) | Attitudes towards recently announced, large-scale change including downsizing, reengineering, total quality management, culture change, and technological innovation | n = 1358 | Not reported | Male = 64 % |

| Organisational Learning Capacity Scale (OLCS) [76] | USA | Human service organisations from a Southern United States city (n = 5) | Organisational readiness for change towards primary prevention, strength-based approach, empowerment, and changing community conditions | n = 125 | 50 % | Female = 79 % |

| Organisational Capacity Measure-Chronic Disease Prevention and Healthy Lifestyle Promotion [81] | Canada | Public health organisations in Canada including government departments, regional health authorities, public health units, and other professional and non-government organisations (n = 216) | Organisational capacity in public health systems to develop, adopt, or implement chronic disease prevention and healthy lifestyle programmes | n = 216 | Not reported | Senior/middle managers Service providers Professional staff |

| Organisational Environment and Processes Scale [89] | USA | Fortune 1000 companies (manufacturing firms, service organisations) and large government agencies (n = 710) | Perceptions of structures and processes related to the adoption of an administrative innovation (Total Quality Management) by Information Systems departments in organisations | n = 123 | 17 % | Senior Information Systems Executives |

| Perceived Characteristics of Innovating (PCI) Scale [87] | Canada | Utility companies, resource-based companies, government departments and a natural grains pool (n = 7) | Perceptions regarding the adoption of personal work stations | n = 540 | 68 % | Executive and middle management First-line supervisors Non-management professionals Technical and clerical staff |

| Perceived Strategic Value and Adoption of eCommerce Scale [90] | Ghana | Small and medium-sized enterprises (200 employees or less) (n = 107) | Perceived strategic value of adopting eCommerce | n = 107 | 54 % | Owners/managers |

| Perceived eReadiness Model (PERM) Questionnaire [85, 86] | South Africa | Business organisations in South Africa (n = 875) | Readiness to adopt eCommerce | n = 150 | 19 % | Chief Executive Officers Managing directors General managers Directors of finance, IT, eCommerce and marketing |

| Readiness for Organisational Change Measure [82] | USA | Government organisation responsible for developing fielding information systems for the Department of Defence | Readiness for a new organisation structure that clarified lines of authority and eliminated duplicate functions | n = 264 | 53 % | Male = 59 % Computer analysts and programmers |

| Technology Acceptance Model 2 (TAM2) Scale [96] | United States | Manufacturing firm, financial services firm, accounting services firm, international investment banking firm (n = 4) | Perceived usefulness and ease of use of a new software system | n = 156 | 78 % | Manufacturing floor supervisors Financial services workers Accounting services workers Investment banking workers |

| Total Quality Management (TQM) and Culture Survey [92] | USA | Manufacturing firm, non-profit service agency, university (n = 3) | Perceived organisational culture and implementation of total quality management practices | n = 886 | 95 % | Manufacturing firm employees Non-profit service agency employees Government employees Service agency employees Educational institute employees |

| Worksite Health Promotion Capacity Instrument (WHPCI) [84] | Germany | Information and communication technology companies in Germany (n = 522) | Willingness and capacity to implement worksite health promotion activities | n = 522 | 21 % | Managing director/board of directors Division head/senior department head Department head Human resources manager/director Owner/proprietor Assistant to executive management |

a Standard 1.8—Describe the composition of the sample from which validity evidence is obtained, including relevant sociodemographic characteristics [25]

Face and content validity

Almost all measures (n = 47) had undergone a process of face and content validation. The development of 36 measures was guided by an existing theory or framework (Additional file 2). No measures were specifically designed to address all constructs considered important for the implementation of innovations by the CFIR. Twenty-six measures had adapted at least some of their items from pre-existing instruments (Additional file 2).

Construct and criterion validity

The internal structure of 45 instruments was determined via EFA (11 of these also used CFA [42, 49, 52, 54, 55, 59, 65, 67, 77, 78, 82, 91–93]), and six studies used CFA alone [39, 40, 68, 72, 75, 83, 94] (Additional file 3). For studies which conducted EFA, 46 % reported that >50 % of the variance was explained by the final factor model. None of the studies that used CFA alone reported acceptable RMSEA (<0.06) or CFI (>0.95). Across all measures, the number of items ranged from 9 to 149, and the number of factors (domains) ranged from 1 to 20. Eight measures were tested for criterion validity for sub-populations with known differences. These measures demonstrated capacity to distinguish between a number of groups with known differences, including the amount of teaching experience [47], familiarisation with technology [59], age [58], and managers and non-managers [77]. Only two measures [41, 82] reported testing for convergent/divergent validity against existing instruments, although only one [82] met the required threshold of having significant positive or negative correlations >0.40 or <0.30 with an external measure. In this instance, these relationships were only reported for some individual domains rather than the total score of the scale.

Internal consistency and test-retest reliability

Fifty of the 51 included measures reported on the internal consistency of either the total scale or the individual domains (Additional file 4). The internal consistency of both the total scale and the domains was reported for four measures [40, 61, 66, 76], the internal consistency of the total scale only was reported for five measures (all alpha’s >0.70) [47, 49, 51, 75, 83], and the internal consistency for the scale domains only was reported for the remaining 41 measures. Twenty measures achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of >0.70 for all of their domains [38, 40, 41, 48, 50–52, 54, 59, 60, 63, 76, 79, 81, 84, 85, 87, 89, 90, 95, 96], indicating that more than 50 % of measures did not meet the acceptable threshold for at least one domain. Three measures were examined for test-retest reliability [47, 73, 84]. The administration period was acceptable (2–14 days) for all measures, and adequate test-retest reliability (Pearson’s correlations >0.70) was achieved for all measures, with the exception of one domain (awareness, r = 0.65) in the Stages of Concern Questionnaire [74].

Responsiveness, acceptability, feasibility, revalidation, and cross-cultural adaptation

Seventeen measures reported acceptability and feasibility, with five studies reporting the time that it took to complete the measure (range 10–70 min; M = 34.6 min) [39, 64, 73, 81, 90] and six studies reporting the proportion of missing items observed following the measure administration (range 1.5–5 %) [52, 59, 63, 67, 75, 84] (Additional file 5). Seven studies examined responsiveness in relation to effect sizes [38, 47, 67, 69, 75, 93, 97], and all but one reported an effect size above the threshold criterion of 0.5 [67], indicating that these measures are capable of detecting moderate size change (Additional file 5). No studies reported floor or ceiling effects. Thirteen measures were revalidated in new settings and with different populations across a number of additional studies [55, 77, 91, 96, 98–112].

A summary of the psychometric criteria reported by the included measures can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of psychometric properties reported for each measure

| Measure | Face/content validity | Construct validity | Criterion validity | Internal consistency | Test-retest reliability | Responsiveness | Acceptability/feasibility | Revalidation/cross-cultural |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schools | ||||||||

| Adopter Characteristics Scale [43] | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Awareness and Concern Instrument [51] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Health Teaching Self-efficacy (HTSE) Scale [47] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| Index of Inter-professional Team Collaboration-Expanded School Mental Health (IITC-ESMH) [50] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| McKinney-Vento Act Implementation Scale (MVAIS) [40] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Organisational Climate Instrument [51] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Perceived Attributes of the Healthy Schools Approach Scale [42] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Policy Characteristics Scale [52] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Role-Efficacy Belief Instrument (REBI) [45] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Rogers’s Adoption Questionnaire [51] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| School Wellness Policy Instrument (WPI) [48] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| School-level Environment Questionnaire—South Africa (SLEQ-SA) [38] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| School Success Profile-Learning Organisation Measure (SSP-LO) [39] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| School Readiness for Reforms-Leader Questionnaire (SRR-LQ) [41] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| School-wide Universal Behaviour Sustainability \Index-School Teams (SUBSIST) [49] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – |

| Teacher Receptivity Measure [44] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Universities/colleges | ||||||||

| Intention to Adopt Mobile Commerce Questionnaire [54, 55] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Perceived Attributes of eHealth Innovations Questionnaire [53] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use Scale [56] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Post-adoption Information Systems Usage Measure [59] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Social Influence on Innovation Adoption Scale [60] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Tertiary Students Readiness for Online Learning (TSROL) Scale [57, 58] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Pharmacies | ||||||||

| Facilitators of Practice Change Scale [63] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Leeds Attitude Towards Concordance (LATCon) Scale (Pharmacists) [62] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Perceived Barriers to the Provision of Pharmaceutical Care Questionnaire [61] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Police/correctional facilities | ||||||||

| Perceptions of Organisational Readiness for Change [65] | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – |

| Receptivity to Organisational Change Questionnaire [64] | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Nursing homes | ||||||||

| Intervention Process Measure (IPM) [67] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| Staff Attitudes to Nutritional Nursing Care (SANN) Scale [66] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Whole communities/multiple settings | ||||||||

| 4-E Telemeter [70, 71] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – |

| Attitudes Towards Asthma Care Mobile Service Adoption Scale [94] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| Intention to Adopt Multimedia Messaging Service Scale [69] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| Systems of Care Implementation Survey (SOCIS) [68, 72] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Stages of Concern Questionnaire (SoCQ) [73, 74] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Telepsychotherapy Acceptance Questionnaire [75] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – |

| Other workplaces/organisations | ||||||||

| Adoption of Customer Relationship Management Technology Scale [88] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Coping with Organisational Change Scale [83] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Data Mining Readiness Index (DMRI) [80] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Group Innovation Inventory (GII) [78, 91] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Intention to Adopt Electronic Data Interchange Questionnaire [79] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Organisational Change Questionnaire-Climate of Change, Processes, and Readiness (OCQ-C, P, R) [77] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Organisational Learning Capacity Scale (OLCS) [76] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Organisational Capacity Measure-Chronic Disease Prevention and Healthy Lifestyle Promotion [81] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Organisational Environment and Processes Scale [89] | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Perceived Characteristics of Innovating (PCI) Scale [87] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Perceived Strategic Value and Adoption of eCommerce Scale [90] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Perceived eReadiness Model (PERM) Questionnaire [85, 86] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Readiness for Organisational Change Measure [82] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Technology Acceptance Model 2 (TAM2) Scale [96] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Total Quality Management (TQM) and Culture Survey [92] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Worksite Health Promotion Capacity Instrument (WHPCI) [84] | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – |

Mapping of measure domains that align with the 37 constructs of the CFIR

The number of measure domains that mapped onto the CFIR constructs ranged from 1 to 19. Relative advantage, networks and communications, culture, implementation climate, learning climate, readiness for implementation, available resources, and reflecting and evaluating were the constructs most frequently addressed by the included measures. Five of the CFIR constructs were not addressed by any measure (Additional file 6). These five constructs were as follows: intervention source, tension for change, engaging, opinion leaders, and champions.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to describe the psychometric properties of measures developed to assess innovations and implementation constructs specifically in public health and community settings. Overall, the psychometric properties of included measures were typically inadequately assessed or not reported. No single measure reported on all key psychometric quality indicators. The majority of studies assessed face, content, construct validity, and internal consistency. However, criterion validity (known-groups), test-retest reliability, and acceptability and feasibility were rarely reported. Only seven measures had responsiveness to change assessed. These findings mirror those of previous reviews [7, 13] that found that few measures demonstrated test-retest reliability, acceptability, or criterion validity.

When measures did report psychometric data, it was typically below the widely accepted thresholds defined in this review. Almost half of the measures that reported undertaking EFA reported that their final factor model explained <50 % of the variance. Furthermore, none of the measures that used CFA alone reported satisfactory RMSEA (<.06) or CFI (>0.95). This suggests that a notable proportion of available implementation measures developed and currently available for use in non-clinical settings are not particularly robust or are prone to misspecification of fit. That only eight of the 51 measures explored criterion validity using known-groups is also concerning. The lack of attention to known-groups validity limits the confidence we can place in these measures being able to detect how groups within community settings (e.g. experienced teachers vs. new teachers) vary in regards to implementation of innovation. This is important for identifying which aspects of an intervention or innovation might need to be adjusted to ensure more robust implementation in the future.

Internal consistency was frequently reported but only 40 % of measures reported that all scale domains had a Cronbach’s alpha >0.70, highlighting a need for further refinement of scale items and revalidation. Only three measures assessed test-retest reliability, another area requiring much greater attention in future studies. Those studies that did assess test-retest reliability performed well, meeting the vast majority threshold criteria. However, the stability of these types of measures over time remains unclear. Acceptability and feasibility data were reported for just 33 % of the measures. Mean completion time for measures was almost 35 min. Although shorter questionnaires have been shown to improve response rates [113], it is unclear what the optimal survey length is while still maintaining the survey validity. Rates of missing data ranged from 1.5 to <5 %, which according to Schafer [114] is acceptable given missing data rates of less than 5 % are likely to be inconsequential. Only 25 % of measures had been revalidated or validated in a different culture. This limits the generalisability of the measures and poses a significant barrier to research translation within potentially underserved communities or cultures [115].

Without more comprehensive assessment of the psychometric properties of these instruments, the ability to ascertain the utility of theories or frameworks to support the implementation of innovations in public health and community settings is limited. For example, understanding the responsiveness of measures is essential for evaluating implementation interventions and ensuring that changes in constructs over time can be detected [116, 117]. Having measures which are acceptable and feasible is also important to the conduct of rigorous research, particularly in more pragmatic research studies [5, 18]. Low survey response rates or high rates of attrition due to onerous research methods can introduce bias and compromise study internal and external validity [118, 119].

Alignment of measure domains with constructs of the CFIR

While some of the CFIR constructs were addressed by domains from multiple measures in this study, five constructs were not assessed by any measure. These were intervention source, tension for change, engaging, opinion leaders, and champions. The development of psychometrically robust measures which can assess these constructs in public health and community settings may be a priority area of research for the field.

The most frequently addressed constructs appeared to fall within the ‘inner setting’ and ‘characteristics of individuals’ domains, suggesting that the focus of measures to date has been on understanding only the immediate environment where the innovation or intervention will be implemented. It appeared that measures addressing ‘outer setting’ or ‘process’ constructs were less frequently observed than other domains. The development of future measures should target these domains of the CFIR to ensure a greater breadth and depth of understanding of all factors which may influence the implementation of evidence into practice in public health and community settings.

Comparison of the current review with the SIRC Instrument Review Project

Despite the similarity in review methodologies utilised by the current review and that undertaken by SIRC [16], few measures have been reported by both reviews. This is not surprising, as although the SIRC review captured some measures developed in education or workplace settings, other public health and community settings were not addressed. Furthermore, the SIRC review used a much broader inclusion criteria with regard to measures of CFIR constructs. For example, for the construct of ‘self-efficacy’, the SIRC review includes all measures of self-efficacy, regardless of the context in which self-efficacy is being examined. In contrast, the current review only includes measures which assess self-efficacy in the context of an individual’s perceived ability to implement the target innovation.

Despite these differences, the use of a common framework (CFIR) for examining constructs captured by different measures in the current review promotes consistency and complements the findings of the SIRC review.

Limitations

It is possible that not all existing implementation measures in public health and community settings were captured by this review. The keywords used to identify measures were limited to ‘questionnaire’, ‘measure’, ‘scale’, or ‘tool’ and other possible terms such as ‘instrument’ and ‘test’ were not used. These terms were excluded due to the likelihood of identifying non-relevant publications related to clinical practice (e.g. surgical instruments, immunologic tests). However, the exclusion of these keywords may have meant that some relevant publications were not identified during the database search. Additionally, the review did not assess measures published in the grey literature and only studies published in English were included. However, it is likely that those measures which were identified represent the best available evidence, given their publication in peer-reviewed journals and indexing in four scientific databases. The psychometric properties that were chosen to be extracted from publications about each measure may have also limited the findings. For example, for studies that utilised CFA, only data pertaining to the RMSEA and CFI were recorded based on recommendations by Schmitt [32]. Included publications may have reported additional CFA metrics (such as goodness of fit (GFI) or the normed fit index (NI)); however, they were not included in this review.

Despite these limitations, the findings from this review are likely to be of value to public health researchers who are looking to identify measures with robust psychometric properties that can be used to assess implementation constructs. There are, however, a small number of constructs for which no measure could be identified. Developing measures which can assess these five remaining constructs will be an important consideration for future research.

Conclusion

Existing measures of implementation constructs for use in public health and community settings require additional testing to enhance their reliability and validity. Further research is also needed to revalidate these measures in different settings and populations. At present, no single measure, or combination of measures, can be used to assess all constructs of the CFIR in public health and community settings. The development of new measures which can assess the broader range of implementation constructs across all of the CFIR domains should continue to be a priority for the field.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Ms. Tara Payling for the assistance with identifying the included publications.

Funding

The study was supported by an infrastructure funding from the University of Newcastle, Hunter Medical Research Institute, and Hunter New England Population Health.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the published article and its supplementary information files.

Authors’ contributions

LW, SY, and TCM developed the aims, the methodology, and the search terms. TCM, FT, TR, AF, ES, MK, and JYO contributed to the abstract and full-text screening and data extraction. TCM led the authorship of the manuscript. All other authors contributed to authorship and all approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CFA

confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI

comparative fit index

- CFIR

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- CINAHL

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- EFA

exploratory factor analysis

- EMBASE

Excerpta Medica database

- GFI

goodness of fit

- IOF

Implementation Outcomes Framework

- MEDLINE

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- NFI

normed fit index

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RMSEA

root mean square error of approximation

- SIRC

Society for Implementation Research Collaboration

Additional files

Summary of the CFIR domains and constructs used to support mapping of included measure domains [19]. (DOCX 32.8 kb)

Contributor Information

Tara Clinton-McHarg, Email: tara.clintonmcharg@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Sze Lin Yoong, Email: serene.yoong@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Flora Tzelepis, Email: flora.tzelepis@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Tim Regan, Email: tim.regan@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Alison Fielding, Email: alison.fielding@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Eliza Skelton, Email: eliza.skelton@newcastle.edu.au.

Melanie Kingsland, Email: melanie.kingsland@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Jia Ying Ooi, Email: jiaying.ooi@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Luke Wolfenden, Phone: +61 2 4924 6567, Email: luke.wolfenden@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

References

- 1.Davies P, Walker A, Grimshaw J. A systematic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implement Sci. 2010;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers D, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:337–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez RG, Lewis CC, Weiner BJ. Instrumentation issues in implementation science. Implement Sci. 2014;9:118. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0118-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabin BA, Purcell P, Naveed S, Moser RP, Henton MD, Proctor EK, Brownson RC, Glasgow RE. Advancing the application, quality and harmonization of implementation science measures. Implement Sci. 2012;7:119. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan SE, Bosch M, Buchan H, Green SE. Measuring organizational and individual factors thought to influence the success of quality improvement in primary care: a systematic review of instruments. Implement Sci. 2012;7:121. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chor KHB, Wisdom JP, Olin SCS, Hoagwood KE, Horwitz SM. Measures for predictors of innovation adoption. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014;42:545–73. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0551-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott T, Mannion R, Davies H, Marshall M. The quantitative measurement of organizational culture in health care: a review of the available instruments. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:923–45. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiner BJ, Amick H, Lee SYD. Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: a review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65:379–436. doi: 10.1177/1077558708317802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King T, Byers JF. A review of organizational culture instruments for nurse executives. J Nurs Adm. 2007;37:21. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200701000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emmons KM, Weiner B, Fernandez ME, Tu SP. Systems antecedents for dissemination and implementation: a review and analysis of measures. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39:87–105. doi: 10.1177/1090198111409748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Squires JE, Estabrooks CA, Gustavsson P, Wallin L. Individual determinants of research utilization by nurses: a systematic review update. Implement Sci. 2011;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDowell I. Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hersen M. Clinician’s handbook of adult behavioral assessment. Boston: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implement Sci. 2015;10:155. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0342-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis CC, Stanick CF, Martinez RG, Weiner BJ, Kim M, Barwick M, Comtois KA. The Society for Implementation Research Collaboration Instrument Review Project: a methodology to promote rigorous evaluation. Implement Sci. 2015;10:2. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0193-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The SIRC Instrument Review Project (IRP): A systematic review and synthesis of implementation science instruments [http://www.societyforimplementationresearchcollaboration.org/sirc-projects/sirc-instrument-project]

- 21.Sampson M, McGowan J, Cogo E, Grimshaw J, Moher D, Lefebvre C. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:944–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenuwine E, Floyd J. Comparison of Medical Subject Headings and text-word searches in MEDLINE to retrieve studies on sleep in healthy individuals. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004;92:349–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clinton-McHarg T, Carey M, Sanson-Fisher R, Shakeshaft A, Rainbird K. Measuring the psychosocial health of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors: a critical review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tzelepis F, Rose SK, Sanson-Fisher RW, Clinton-McHarg T, Carey ML, Paul CL. Are we missing the Institute of Medicine’s mark? A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures assessing quality of patient-centred cancer care. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Educational Research Association. American Psychological Association. National Council on Measurement in Education . Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mokkink L, Terwee C, Patrick D, Alonso J, Stratford P, Knol D, Bouter L, de Vet H. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:539–49. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anastasi A, Urbina S. Psychological testing. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohr KN, Aaronson NK, Alonso J, Audrey-Burnam M, Patrick DL, Perrin EB, Roberts JS. Evaluating quality-of-life and health status instruments: development of scientific review criteria. Clin Ther. 1996;18:979–92. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(96)80054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaiser HF. Directional statistical decisions. Psychol Rev. 1960;67:160–7. doi: 10.1037/h0047595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Pearson; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Model. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitt TA. Current methodological considerations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2011;29:304–21. doi: 10.1177/0734282911406653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubin A, Bellamy J. Practitioner’s guide to using research for evidence-based practice. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marx RG, Menezes A, Horovitz L, Jones EC, Warren RF. A comparison of two time intervals for test-retest reliability of health status instruments. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:730–5. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedhazur EJ, Schmelkin LP. Measurement, design, and analysis: an integrated approach. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aldridge JM, Laugksch RC, Fraser BJ. School-level environment and outcomes-based education in South Africa. Learn Environ Res. 2006;9:123–47. doi: 10.1007/s10984-006-9009-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowen GL, Rose RA, Ware WB. The reliability and validity of the school success profile learning organization measure. Eval Program Plann. 2006;29:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2005.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canfield JP, Teasley ML, Abell N, Randolph KA. Validation of a Mckinney-Vento Act implementation scale. Res Soc Work Pract. 2012;22:410–9. doi: 10.1177/1049731512439758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chatterji M. Measuring leader perceptions of school readiness for reforms: use of an iterative model combining classical and Rasch methods. J Appl Meas. 2001;3:455–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deschesnes M, Trudeau F, Kebe M. Psychometric properties of a scale focusing on perceived attributes of a health promoting school approach. Can J Public Health. 2009;100:389–92. doi: 10.1007/BF03405277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gingiss PL, Gottlieb NH, Brink SG. Measuring cognitive characteristics associated with adoption and implementation of health innovations in schools. Am J Health Promot. 1994;8:294–301. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-8.4.294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gingiss PL, Gottlieb NH, Brink SG. Increasing teacher receptivity toward use of tobacco prevention education programs. J Drug Educ. 1994;24:163–76. doi: 10.2190/2UXC-NA52-CAL0-G9RJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayes DM. Toward the development and validation of a curriculum coordinator Role-efficacy Belief Instrument for sexuality education. J Sex Educ Ther. 1992;18:127–35. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hume A, McIntosh K. Construct validation of a measure to assess sustainability of school-wide behavior interventions. Psychol Sch. 2013;50:1003–14. doi: 10.1002/pits.21722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kingery PM, Holcomb JD, Jibaja-Rusth M, Pruitt BE, Buckner WP. The health teaching self-efficacy scale. J Health Educ. 1994;25:68–76. doi: 10.1080/10556699.1994.10603006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lambert LG, Monroe A, Wolff L. Mississippi elementary school teachers’ perspectives on providing nutrition competencies under the framework of their school wellness policy. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42:271–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McIntosh K, MacKay LD, Hume AE, Doolittle J, Vincent CG, Horner RH, Ervin RA. Development and initial validation of a measure to assess factors related to sustainability of school-wide positive behavior support. J Posit Behav Interv. 2011;13:208–18. doi: 10.1177/1098300710385348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mellin EA, Bronstein L, Anderson-Butcher D, Amorose AJ, Ball A, Green J. Measuring interprofessional team collaboration in expanded school mental health: model refinement and scale development. J Interprof Care. 2010;24:514–23. doi: 10.3109/13561821003624622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steckler A, Goodman RM, McLeroy KR, Davis S, Koch G. Measuring the diffusion of innovative health promotion programs. Am J Health Promot. 1992;6:214–24. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tuytens M, Devos G. Teachers’ perception of the new teacher evaluation policy: a validity study of the policy characteristics scale. Teach Teach Educ. 2009;25:924–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Atkinson NL. Developing a questionnaire to measure perceived attributes of eHealth innovations. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31:612–21. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.31.6.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chung KC. Gender, culture and determinants of behavioural intents to adopt mobile commerce among the Y generation in transition economies: evidence from Kazakhstan. Behav Inf Technol. 2014;33:743–56. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2013.805243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chung K-C, Holdsworth DK. Culture and behavioural intent to adopt mobile commerce among the Y Generation: comparative analyses between Kazakhstan, Morocco and Singapore. Young Consumers. 2012;13:224–41. doi: 10.1108/17473611211261629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13:319–40. doi: 10.2307/249008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pillay H, Irving K, McCrindle A. Developing a diagnostic tool for assessing tertiary students’ readiness for online learning. Int J Learn Tech. 2006;2:92–104. doi: 10.1504/IJLT.2006.008696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pillay H, Irving K, Tones M. Validation of the diagnostic tool for assessing tertiary students’ readiness for online learning. High Educ Res Dev. 2007;26:217–34. doi: 10.1080/07294360701310821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saeed KA, Abdinnour S. Understanding post-adoption IS usage stages: an empirical assessment of self-service information systems. Inf Syst J. 2013;23:219–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2575.2011.00389.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Talukder M, Quazi A. The impact of social influence on individuals’ adoption of innovation. J Org Comp Elect Com. 2011;21:111–35. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fang Y, Yang S, Feng B, Ni Y, Zhang K. Pharmacists’ perception of pharmaceutical care in community pharmacy: a questionnaire survey in Northwest China. Health Soc Care Community. 2011;19:189–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kansanaho HM, Puumalainen II, Varunki MM, Airaksinen MSA, Aslani P. Attitudes of Finnish community pharmacists toward concordance. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1946–53. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roberts AS, Benrimoj SI, Chen TF, Williams KA, Aslani P. Practice change in community pharmacy: quantification of facilitators. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:861–8. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cochran JK, Bromley ML, Swando MJ. Sheriff’s deputies’ receptivity to organizational change. Policing. 2002;25:507–29. doi: 10.1108/13639510210437014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taxman FS, Henderson C, Young D, Farrell J. The impact of training interventions on organizational readiness to support innovations in juvenile justice offices. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014;41:177–88. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0445-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Christensson L, Unosson M, Bachrach-Lindstrom M, Ek AC. Attitudes of nursing staff towards nutritional nursing care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2003;17:223–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Randall R, Nielsen K, Tvedt SD. The development of five scales to measure employees’ appraisals of organizational-level stress management interventions. Work Stress. 2009;23:1–23. doi: 10.1080/02678370902815277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boothroyd RA, Greenbaum PE, Wang W, Kutash K, Friedman RM. Development of a measure to assess the implementation of children’s systems of care: the systems of care implementation survey (SOCIS) J Behav Health Serv Res. 2011;38:288–302. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chang SE, Pan YHV. Exploring factors influencing mobile users’ intention to adopt multimedia messaging service. Behav Inf Technol. 2011;30:659–72. doi: 10.1080/01449290903377095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]