Abstract

Background

Refractory post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock (PCCS) is a relatively rare phenomenon that can lead to rapid multi-organ dysfunction syndrome and is almost invariably fatal without advanced mechanical circulatory support (AMCS), namely extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or ventricular assist devices (VAD). In this multicentre observational study we retrospectively analyzed the outcomes of salvage venoarterial ECMO (VA ECMO) and VAD for refractory PCCS in the 3 adult cardiothoracic surgery centres in Scotland over a 20-year period.

Methods

The data was obtained through the Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen cardiac surgery databases. Our inclusion criteria included any adult patient from April 1995 to April 2015 who had received salvage VA ECMO or VAD for PCCS refractory to intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) and maximal inotropic support following adult cardiac surgery.

Results

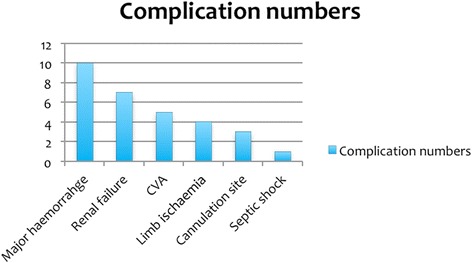

A total of 27 patients met the inclusion criteria. Age range was 34–83 years (median 51 years). There was a large male predominance (n = 23, 85 %). Overall 23 patients (85 %) received VA ECMO of which 14 (61 %) had central ECMO and 9 (39 %) had peripheral ECMO. Four patients (15 %) were treated with short-term VAD (BiVAD = 1, RVAD = 1 and LVAD = 2). The most common procedure-related complication was major haemorrhage (n = 10). Renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy (n = 7), fatal stroke (n = 5), septic shock (n = 2), and a pseudo-aneurysm at the femoral artery cannulation site (n = 1) were also observed. Overall survival to hospital discharge was 40.7 %. All survivors were NYHA class I-II at 12 months’ follow-up.

Conclusion

AMCS for refractory PCCS carries a survival benefit and achieves acceptable functional recovery despite a significant complication rate.

Keywords: Extracorporeal circulation, Heart-assist devices, Post-cardiotomy, Shock

Background

Cardiogenic shock following cardiac surgery can affect as many as 2–6 % of patients undergoing routine surgical coronary revascularization or valve surgery [1–4]. Although the majority of these patients respond to inotropic support and/or intra-aortic balloon pump counter pulsation (IABP) support, 0.5–1.5 % of patients demonstrate a rapid and progressive decline in their haemodynamic parameters in the immediate aftermath of cardiopulmonary bypass [5]. The occurrence of post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock (PCCS) can be unpredictable and can occur in patients with normal preoperative myocardial function as well as those with pre-existing impaired function [6]. Refractory PCCS leads to vital organ hypoperfusion and is almost universally fatal [4, 7–9] without the use of advanced mechanical circulatory support (AMCS) devices such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or ventricular assist devices (VAD).

In our previous study we looked at the outcomes of AMCS utilization at the Edinburgh heart center’s cardiothoracic surgery department (a non-transplant, intermediate-sized, adult cardiothoracic surgery centre) in Scotland [10]. This current multicentre observational study aims to consolidate our previous findings and looks at the 20-year outcomes of AMCS utilization to salvage refractory PCCS patients in all the 3 cardiothoracic surgery centres in Scotland.

Methods

Scottish adult cardiothoracic surgical services are provided by three regional centres covering a population of 5.2 million individuals [11]. The relevant data was collected from the databases of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (surgical case load ≈ 900/year), the Golden Jubilee National Hospital in Glasgow (surgical case load ≈ 1300/year), and the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary (surgical case load ≈ 500/year). Our inclusion criteria included any adult patient from April 1995 to April 2015 who had received salvage VA ECMO or VAD for PCCS refractory to IABP and inotropic support following adult cardiac surgery. We acquired information regarding the patients’ 12 month follow-up status by accessing the cardiology follow-up clinic letters on the TrakCareR system in Edinburgh, the AMCS database in Glasgow, and through making direct enquiries with the surgeons involved in the long-term outcomes of the patients in Aberdeen via email and telephone communications.

The AMCS devices utilised at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh over the defined study period were LevitronixR CentriMag II for ECMO and Medtronic Bio-MedicusR 560 for short-term VAD support. Over the same time period, the AMCS devices used at the Golden Jubilee National Hospital in Glasgow and the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary cardiac surgical units was the CentriMag device for both VA ECMO and short-term VAD support.

Results

A total of 28 patients met the inclusion criteria with one patient excluded due to lack of recorded information in the TrakCareR database regarding the type of AMCS support used, any potential complications and the short and the long-term outcomes of this individual. Overall, 16 patients from the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh met the inclusion criteria, 8 patients from the Golden Jubilee National Hospital in Glasgow and 3 patients from Aberdeen Royal Infirmary cardiothoracic surgery unit. The reason why more cases belonged to Edinburgh rather than Glasgow, despite the latter being a larger unit, was because AMCS was rarely used to salvage refractory PCCS patients in the west of Scotland prior to 2007 (the year of the merger between Glasgow Royal Infirmary and the Glasgow Western Infirmary forming the Golden Jubilee National Hospital).

Of the total 27 patients from the 3 centres, the age range was 34–83 years (median 59 years). There was a large male predominance of 23 (85 %). Four patients (15 %) had undergone re-operative cardiac surgery. One patient (3.7 %) had undergone AMCS following the repair of a traumatic ascending aortic transection after a road traffic accident. Overall, 23 patients (85 %) had received a single run of VA ECMO of which 14 (61 %) had received central ECMO and 9 (39 %) had received peripheral ECMO. Four patients (15 %) had short-term VADs (1 BiVAD, 1 RVAD and 2 LVAD). The mean duration of AMCS was approximately 5.43 days (Range < 1 day–33 days). The most common procedure-related complication was major haemorrhage (37 %). Renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy (26 %), stroke (19 %) and peripheral limb ischaemia (15 %, Fig. 1) were also recorded. Logistic EuroSCORE ranged from 2.08 to 73.26. More detailed patient baseline characteristics are tabulated in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Bar chart illustrating the number and nature of complications within cohort

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics

| Age & Gender | Date of surgery | Original operation | Duration and Mode of AMCS | AMCS Complication/s | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 76 year old male | 2012 | Re-do sternotomy and AVR | Salvage peripheral VA ECMO due to postoperative pulmonary haemorrhage and cardiogenic shock | Femoral artery cannulation site pseudoaneurysm | Alive |

| NYHA I (No breathlessness of exertion, back to work) | ||||||

| Major haemorrhage from cannulation site | ||||||

| Patient 2 | 40 year old male | 2014 | Re-do, Re-do sternotomy for type A aortic dissection: Bentall procedure | Salvage RVAD due to VF arrest and severe LVSD after weaning from CPB | Major haemorrhage and re-exploration in the operating theatre | Alive |

| NYHA II (Breathless on exertion) | ||||||

| Patient 3 | 82 year old male | 2006 | MV Repair and CABG | 3 Days | Could not be weaned from ECMO with severe biVent failure and | Died in CTICU |

| VA ECMO as unable to wean from CPB | COD: BiVent failure | |||||

| Patient 4 | 72 year old Female | 2011 | AVR | 9 Days | Septic shock | Died in CTICU |

| VA ECMO as unable to come off CPB | Limb ischaemia | COD: Septic shock | ||||

| Patient 5 | 71 year old male | 2011 | CABG and AVR | 2 Days | ECMO cannulation site bleeding and haematoma explored | Died in CTICU |

| Peripheral VA ECMO as unable to come off CPB | COD: Shock (unknown cause) | |||||

| Renal failure a | ||||||

| Patient 6 | 83 year old female | 2012 | MVR and CABG | <1 Day | None | Died in CTICU |

| Peripheral VA ECMO as unable to wean from CPB | COD: BiVent failure | |||||

| Patient 7 | 70 year old male | 2013 | Re-do sternotomy and AVR | 33 Days | Major CVA | Died in HDU |

| VA ECMO for cardiac failure. Successfully weaned from ECMO | COD: severe Respiratory failure | |||||

| Patient 8 | 72 year old male | 2013 | Re-do sternotomy and AVR | <1 Day | ECMO cannulation femoral artery dissection | Died in CTICU |

| VA ECMO after iatrogenic aortic dissection leading to cardiogenic shock during Femoral cannulation for CPB | COD: Major CVA | |||||

| Major haemorrhage | ||||||

| Major CVA | ||||||

| Patient 9 | 51 year old male | 2013 | Re-suspension of Aortic valve and repair of type A aortic dissection | 1 Day | Major cannulation site haemorrhage | Died in CTICU |

| Peripheral VA ECMO for cardiogenic shock | COD: Haemorrahgic shock and BiVent failure | |||||

| Patient 10 | 34 year old female | 2014 | IVC Leiomyosarcoma resection | 3 Days | None | Died in CTICU |

| VA ECMO for postoperative cardiogenic shock for intraoperative MI | COD: BiVent failure from acute MI | |||||

| Patient 11 | 65 year old male | 2013 | CABG | 2 Days | Renal failurea | Died in CTICU |

| Salvage VA ECMO for cardiogenic shock | Hepatic failure | COD: MODS | ||||

| Pulmonary oedema | ||||||

| Patient 12 | 71 year old male | 2015 | CABG | 3 Days | Major haemorrhag e: Re-opening for bleeding x4 | Died in CTICU |

| VA ECMO as unable to wean from CPB | COD: biventricular failure and septic shock | |||||

| limb ischaemia | ||||||

| Patient 13 | 49 year old male | 1997 | CABG | VA ECMO as unable to wean from CPB | Note recorded | Alive |

| (Died 2004) | ||||||

| NYHA II | ||||||

| Patient 14 | 69 year old male | 2004 | MVR and CABG for mitral valve IE | VA ECMO as unable to wean from CPB | CVA and seizures | Alive |

| Renal failure a | NYHA II | |||||

| Patient 15 | 41 year old female | 2005 | Aortic transection and diaphragm rupture | VA ECMO | Not recorded | Alive |

| NYHA I | ||||||

| Patient 16 | 59 year old male | 2006 | Type A aortic dissection | 2 Days | Not recorded | Died |

| Peripheral VA ECMO as unable to wean from CPB | COD: Bivent failure | |||||

| Patient 17 | 21 year old male | 2014 | AVR | 3 days | ECMO cannulation site bleeding-required re-exploration | Alive |

| Peripheral VA ECMO | NYHA I | |||||

| Cardiac tamponade | ||||||

| Patient 18 | 51 year old male | 2014 | AVR | 6 days | CVA and Seizures | Died in ICU |

| Peripheral VA ECMO | limb ischaemia | COD: status epilepticus | ||||

| Patient 19 | 46 year old male | 2014 | CABG | 2 days | Major haemorrahage | Died in ICU |

| Peripheral VA ECMO converted to central VA ECMO due to peripheral ischaemia | COD: MODS | |||||

| Limb ischaemia/compartment syndrome-bilateral fasciotomies | ||||||

| Renal failurea | ||||||

| Patient 20 | 54 year old male | 2015 | CABG and AVR | 3 days | SVT/VT | Alive |

| VA ECMO for cardiogenic shock | Major intra-abdominal haemorrhage requiring laparotomy | NYHA II (Neuropathic leg pain) | ||||

| Limb ischaemia | ||||||

| Patient 21 | 56 year old male | 2015 | AVR | 3 days | CVA (occipital infarcts) | Alive |

| Peripheral VA ECMO for cardiogenic shock | NYHA I (Visual difficulties) | |||||

| Patient 22 | 64 year old male | 2015 | AVR | 1 day | Vasoplegia | Died |

| VA ECMO | MODS | COD: AV dissociation | ||||

| Patient 23 | 52 year old male | 2015 | CABG | 1 day | MODS | Died |

| VA ECMO | COD: MODS | |||||

| Patient 24 | 64 year old male | 2015 | AVR | 7 days | None | Alive |

| VA ECMO | NYHA I | |||||

| Patient 25 | 50 year old male | 2014 | AVR | 23 days | Renal failurea | Alive |

| BiVAD | NYHA I | |||||

| Haemothorax/mediastinal collection requiring re-operation | ||||||

| Patient 26 | 54 year old male | 2015 | Bentall’s procedure and CABG surgery | 2 days | Hepatic failure | COD: MODS |

| LVAD acute LV failure | Renal failure pleasea | |||||

| Patient 27 | 61 year old male | 2003 | CABG | 11 days | Respiratory failure | Alive |

| LVAD for acute LV failure | Renal failurea | NYHA II |

Abbreviations: ACS Acute coronary syndrome, AF atrial fibrillation, AMCS Advanced mechanical circulatory support, AVR Aortic valve replacement, CABG Coronary artery bypass grafting surgery, CPB Cardiopulmonary bypass, COD cause of death, BiVent failure BiVentricular failure, MVR Mitral valve replacement, IE Infective endocarditis, CVA Cerebrovascular accident, IVC Inferior vena-cava, NYHA New York Heart Association, CTICU cardiothoracic Intensive care unit, HDU High dependency unit, Implantable cardioverter defibrillator, MI Myocardial infarction, LVSD Left ventricular systolic dysfunction, TVD triple vessel coronary artery disease, LV left ventricular, MR Mitral regurgitation, PVD Peripheral vascular disease, MODS Multi-organ dysfunction syndrome, VF Ventricular fibrillation, VAD Ventricular assist device, VA Veno-Arterial

aAll patients with renal failure required renal replacement therapy

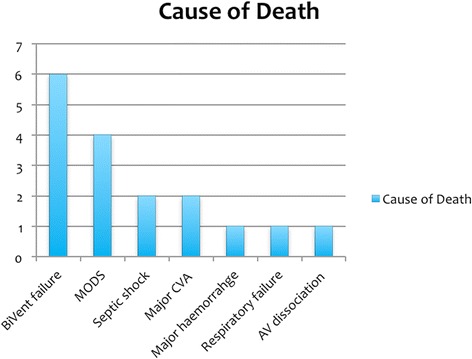

The most common cause of death (COD) was refractory biventricular failure that failed to recover sufficiently to allow weaning from AMCS (22.2 %, Fig. 2). In these patients care was withdrawn. One patient died due to a combination of biventricular failure and haemorrhagic shock and another patient died from a combination of biventricular failure and septic shock whilst on VA ECMO. The survival rate to hospital discharge was 40.7 % (Fig. 3). The follow-up data showed that the survivors were all NYHA class I-II functional status at 12 months.

Fig. 2.

Bar chart illustrating the number and causes of death within cohort. AV: atrioventricular

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve of survival, x-axis represents follow-up (FU) in days and y-axis represents cumulative survival (Cum survival)

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Fisher’s exact and Pearson’s chi2 tests. Univariate analysis was performed. Table 2 demonstrates the baseline statistics data and the analytical methods used in this study.

Table 2.

Demonstrates variables used for statistical analysis. Fisher’s exact test and Pearson’s chi test (Log. EuroSCORE) were utilized for statistical analysis

| Factors attributed to mortality and statistical analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics analyzed | Alive | Dead | Odds ratio (95 % Conf. interval) | p-value |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 0–65 | 8 | 10 | 2.8 (0.362853–33.74714) | 0.24 |

| > 65 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 9 | 14 | 1.928571 (0.1270413–112.3145) | 0.5 |

| Female | 1 | 3 | ||

| Type of center | ||||

| Transplant | 4 | 5 | 0.625 (0.0921389–4.488993) | 0.44 |

| Non-transplant | 6 | 12 | ||

| Prev. cardiac surgery | ||||

| Re-do surgery | 2 | 2 | 0.5333333 (0.0335265–8.873345) | 0.48 |

| First time surgery | 8 | 15 | ||

| Surgical complexity | ||||

| Isolated surgery | 6 | 10 | 1.05 (0.1662785–7.107629) | 0.64 |

| Complex surgery | 4 | 7 | ||

| Type of Support | ||||

| VAD | 3 | 1 | 0.1458333 (0.0026189–2.352801 | 0.13 |

| ECMO | 7 | 16 | ||

| Duration of Support | ||||

| 0–7 days | 8 | 15 | 0.5333333 (0.0335265 8.873345) | 0.47 |

| > 7 days | 2 | 2 | ||

| Support complications | ||||

| Major haemorrhage | 5 | 5 | 0.4166667 (0.0620347–2.804408) | 0.25 |

| No major haemorrhage | 5 | 12 | ||

| Major CVA | 1 | 4 | 2.769231 (0.2140667–151.2664) | 0.37 |

| No major CVA | 9 | 13 | ||

| Renal failure | 3 | 4 | 0.7179487 (0.0910803–6.420841) | 0.52 |

| No renal failure | 7 | 13 | ||

| Log. EuroSCORE | ||||

| 0–10 | 1 | 3 | 0.36 (Pearson’s chi2 test) | |

| 10–20 | 1 | 6 | ||

| > 20 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Score not available | 4 | 5 | ||

Table information: Prev.cardiac surgery denotes whether the patient had had previous cardiac surgery through median sternotomy (i.e. redo surgery). Isolated surgery refers to whether the operation was isolated coronary artery bypass grafting surgery (CABG) or single valve surgery. Complex cardiac surgery refers to combined valve, CABG and/or aortic surgery. Type of center denotes whether the operating hospital in which the operation was performed was a cardiopulmonary transplant center. Log. EuroSCORE refers to logistic EuroSCORE

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that AMCS used for the treatment of refractory PCCS can lead to good outcomes for a significant number of patients, with 40.7 % surviving to hospital discharge and all surviving patients were graded as either NYHA class I or II at 12 months’ post-discharge. Without AMCS, it is likely that the vast majority of these patients would have died. Ours is also the first multi-centre study of its kind to emerge from the UK and one of the few studies to examine functional outcomes post AMCS utilisation for refractory PCCS.

Recent evidence has demonstrated that modern, continuous-flow AMCS devices, such as the CentriMagR that was used in our centres, can lead to improved survival in patients with PCCS [12–14]. In the largest cohort, Hernandez et al. [3] collated data from 5735 patients who underwent salvage VAD for refractory PCCS. They reported a 54.1 % survival rate to hospital discharge and concluded that VAD is a valuable, life-saving therapeutic manoeuvre. By comparison, the survival rate in our study was lower but firm conclusions are difficult given the low number of patients in our cohort. However, other smaller studies (relative to the Hernandez study) [5, 15–18] all using either ECMO or VAD for refractory PCCS, reported less impressive survival to hospital discharge rates of 24.8 %–37 % and a 5 year survival of 13.7 %–16.9 %. Unfortunately, we do not have long-term survival data as many of the survivors were ultimately discharged from the outpatient clinics when no further medical or surgical interventions were required, hence longer term follow up data post out-patient clinic discharge had not been recorded in the database.

We identified advanced age to be a factor leading to an adverse outcome, although again, owing to our smaller numbers, this did not reach statistical significance. Most (64 %) of the survivors were under 60 years of age. Furthermore, the emergent nature of surgery and pre-existing, preoperative severe left ventricular impairment were also identified as probable factors leading to an adverse outcome.

Evidence suggests that early device implantation [6] and appropriate patient selection through a multidisciplinary team approach is paramount to an optimal outcome [10]. There are no national or local protocols for identifying suitable patients for AMCS with refractory PCCS in Scotland: instead, decisions are based on a case-by-case assessment involving a multidisciplinary team (cardiac surgeon, department head, anaesthetist, and perfusionist) in each of the three hospital sites. We continue to believe that this is the best approach to patient selection rather than a standardised algorithmic approach because it ensures an ethically appropriate decision for the patient whilst optimising the cost-benefit equation. The decision regarding when to initiate AMCS support was made for most patients whilst in theatre in those whom weaning from CPB was not possible, although a few were commenced AMCS whilst in ICU. The time to AMCS and how this correlates to survival is an important variable that regrettably was not consistently recorded in our patient cohort.

AMCS devices are expensive [9, 19, 20] and this, coupled with a potentially prolonged length of stay in ICU, means that cost is an important factor in the decision-making process, particularly within the UK NHS. Indeed, decision-makers have opted to centralise AMCS funding to a restricted number of the larger cardiothoracic centres [21], invariably depriving other units of this potentially life-saving resource. Understandably, this has led to expressions of consternation [21]. In our cohort, the longest duration on AMCS was 33 days (patient 7). This patient was successfully weaned from VA ECMO but died whilst in critical care from a stroke, which may have been a complication from AMCS employment.

The NYHA functional outcomes for our patients were also very positive. Unfortunately, many previous AMCS studies for refractory PCCS do not report such findings, although we did identify two studies, each with similar outcomes to ours. Ko et al. [17] detailed a cohort of 76 patients undergoing ECMO support for refractory PCCS. They reported that all survivors were of NYHA classes I or II at 32 +/− 22 month follow-up. Pennington et al. [15] reported on refractory PCCS support with VAD and found that all survivors were “leading active lives”. In 72.7 % of their survivors, ejection fraction had normalized on follow-up echocardiography.

Clearly, given that we only identified 27 patients undergoing AMCS over a 20-year period, and despite our pooled hospital case volume, we acknowledge that the Scottish approach to institution of AMCS for refractory PCCS has been relatively conservative. This can partly be explained by the fact that salvage AMCS was not employed in the west of Scotland until 2007. Also, our general approach to institution of AMCS dictates that such modalities are instituted only if there is a reversible cause of the cardiogenic shock, which is reflected by our reasonable survival rate. Other possible reasons for underutilization may include: scarcity of resources, prohibitive costs, and lack of consistent evidence for the benefit of AMCS.

The decision to institute AMCS must also be balanced with due consideration of the associated risks of this invasive modality, many of which are potentially life-threatening. Common device-related complications include: haemorrhage, thrombus formation and embolization, stroke, device-related infection, limb ischaemia, and multi-organ dysfunction syndrome/failure [1, 2, 15, 17, 22, 23]. In our cohort, the most common procedure-related complication was major haemorrhage. Renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy, stroke, and peripheral limb ischaemia also occurred with comparable rates to previous studies.

Given the scarcity of donor hearts in the UK, research continues to focus on implantable AMCS devices as a bridge to recovery, bridge to transplant, or as destination therapy [19]. However, none of our patients were transplanted during the study period and none had implantable long-term VADs.

Finally, this study is limited by the small number of subjects (as previously discussed) and its retrospective nature. It nevertheless reaffirms the findings of our previous study, which reported a good survival rate and acceptable quality of life for patients who received AMCS for refractory PCCS and survived to hospital discharge.

Conclusions

AMCS devices can be used to salvage a significant proportion of patients with refractory PCCS who would otherwise not survive. These patients are also likely to enjoy a reasonable quality of life. However, ACMS devices are associated with high rates of severe, systemic and device-related complications as well as being costly. Multidisciplinary teams experienced with patient selection and decision-making are imperative to help ensure appropriate use of AMCS and the best patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The data gathered for this study can be retrieved from the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Golden Jubilee National Hospital and Aberdeen Royal Infirmary cardiothoracic surgery databases and TrakCareR databases. The raw data can be requested from the corresponding author (M. Khorsandi).

Authors’ contributions

MK principal investigator, manuscript preparation and drafting, data collection, SD: manuscript drafting, AS manuscript drafting and assistance with data collection, KB: manuscript drafting, FM: assistance with data collection, OB: statistical analysis, PC: manuscript drafting, VZ: manuscript drafting, GB: manuscript drafting, NAA: project supervisor and manuscript drafting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Meeting presentation

Oral presentation at the SCTS conference Birmingham, UK, 13-15/March/2016.

Abbreviations

- ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- AMCS

Advanced mechanical circulatory support

- AVR

Aortic valve replacement

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass grafting surgery

- CPB

Cardiopulmonary bypass

- COD

Cause of death

- BiVent failure

BiVentricular failure

- MVR

Mitral valve replacement

- IE

Infective endocarditis

- CVA

Cerebrovascular accident

- IVC

Inferior vena-cava

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- CTICU

Cardiothoracic Intensive care unit

- HDU

High dependency unit

- ICD

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- LVSD

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction

- TVD

triple vessel coronary artery disease

- LV

left ventricular

- MR

Mitral regurgitation

- PVD

Peripheral vascular disease

- MODS

Multi-organ dysfunction syndrome

- VF

Ventricular fibrillation

- VAD

Ventricular assist device

- VA

Veno-Arterial

Contributor Information

Maziar Khorsandi, Phone: 0044-7737708453, Email: maziarkhorsandi@doctors.org.uk.

Scott Dougherty, Email: s.dougherty_imca@yahoo.com.

Andrew Sinclair, Email: Andrew.Sinclair@gjnh.scot.nhs.uk.

Keith Buchan, Email: keith.buchan@nhs.net.

Fiona MacLennan, Email: feefee_87@hotmail.com.

Omar Bouamra, Email: omar.bouamra@manchester.ac.uk.

Philip Curry, Email: philipalancurry@gmail.com.

Vipin Zamvar, Email: zamvarv@hotmail.com.

Geoffrey Berg, Email: geoffberg@nhs.net.

Nawwar Al-Attar, Email: nawwar.al-attar@gjnh.scot.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.Muehrcke DD, McCarthy PM, Stewart RW, Foster RC, Ogella DA, Borsh JA, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61(2):684–91. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)01042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeRose JJ, Jr, Umana JP, Argenziano M, Catanese KA, Levin HR, Sun BC, et al. Improved results for postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock with the use of implantable left ventricular assist devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64(6):1757–62. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)01107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez AF, Grab JD, Gammie JS, O’Brien SM, Hammill BG, Rogers JG, et al. A decade of short-term outcomes in post cardiac surgery ventricular assist device implantation: data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons' National Cardiac Database. Circulation. 2007;116(6):606–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohite PN, Sabashnikov A, Patil NP, Saez DG, Zych B, Popov AF, et al. Short-term ventricular assist device in post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock: factors influencing survival. J Artif Organs. 2014;17(3):228–35. doi: 10.1007/s10047-014-0773-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rastan AJ, Dege A, Mohr M, Doll N, Falk V, Walther T, et al. Early and late outcomes of 517 consecutive adult patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139(2):302–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado DH, Rao V, Ross HJ, Verma S, Smedira NG. Mechanical circulatory assistance: state of art. Circulation. 2002;106:2046–50. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000035281.97319.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein DJ, Oz MC. Mechanical support for postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12(3):220–8. doi: 10.1053/stcs.2000.9666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beurtheret S, Mordant P, Paoletti X, Marijon E, Celermajer DS, Leger P, et al. Emergency circulatory support in refractory cardiogenic shock patients in remote institutions: a pilot study (the cardiac-RESCUE program) Eur Heart J. 2013;34(2):112–20. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borisenko O, Wylie G, Payne J, Bjessmo S, Smith J, Firmin R, et al. The cost impact of short-term ventricular assist devices and extracorporeal life support systems therapies on the National Health Service in the UK. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;19(1):41–8. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivu078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khorsandi M, Shaikhrezai K, Prasad S, Pessotto R, Walker W, Berg G, et al. Advanced mechanical circulatory support for post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock: a 20-year outcome analysis in a non-transplant unit. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;11(1). DOI: 10.1186/s13019-016-0430-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.The official gateway to Scotland 2011 [Available from: http://www.scotland.org/about-scotland/facts-about-scotland/population-of-scotland/. Accessed 11 July 2016.

- 12.Akay MH, Gregoric ID, Radovancevic R, Cohn WE, Frazier OH. Timely use of a CentriMag heart assist device improves survival in postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. J Card Surg. 2011;26(5):548–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2011.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peura JL, Colvin-Adams M, Francis GS, Grady KL, Hoffman TM, Jessup M, et al. Recommendations for the use of mechanical circulatory support: device strategies and patient selection: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126(22):2648–67. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182769a54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikus E, Tripodi A, Calvi S, Giglio MD, Cavallucci A, Lamarra M. CentriMag venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support as treatment for patients with refractory postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. ASAIO J. 2013;59(1):18–23. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3182768b68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pennington DG, McBride LR, Swartz MT, Kanter KR, Kaiser GC, Barner HB, et al. Use of the Pierce-Donachy ventricular assist device in patients with cardiogenic shock after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;47(1):130–5. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta SM, Aufiero TX, Pae WE, Jr, Miller CA, Pierce WS. Results of mechanical ventricular assistance for the treatment of post cardiotomy cardiogenic shock. ASAIO J. 1996;42(3):211–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ko WJ, Lin C, Chen RJ, Wang SS, Lin FY, Chen YS, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for adult postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:538–45. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doll N, Kiaii B, Borger M, Bucerius J, Kramer K, Schmitt D, et al. Five year results of 219 consecutive patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after refractory postoperative cardiogenic shock. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:151–7. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emin A, Rogers CA, Parameshwar J, Macgowan G, Taylor R, Yonan N, et al. Trends in long-term mechanical circulatory support for advanced heart failure in the UK. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(10):1185–93. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller LW, Guglin M, Rogers J. Cost of ventricular assist devices: can we afford the progress? Circulation. 2013;127(6):743–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.139824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westaby S, Taggart D. Inappropriate restrictions on life saving technology. Heart. 2012;98(15):1117–9. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zumbro GL, Kitchens WR, Shearer G, Harville G, Bailey L, Galloway RF. Mechanical assistance for cardiogenic shock following cardiac surgery, myocardial infarction, and cardiac transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1987;44(1):11–3. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)62344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao XJ, Luo Z, Ye CX, Fan RX, Yi DH, Ji SY, et al. The short-term pulsatile ventricular assist device for postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock: a clinical trial in China. Artif Organs. 2009;33(4):373–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2009.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data gathered for this study can be retrieved from the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Golden Jubilee National Hospital and Aberdeen Royal Infirmary cardiothoracic surgery databases and TrakCareR databases. The raw data can be requested from the corresponding author (M. Khorsandi).