Comparative analysis of chlorina and cpSRP mutants provides the novel genetic evidence for the flexible organization of light-harvesting complexes and their dynamic and reversible allocation to the two photosystems.

Abstract

State transitions in photosynthesis provide for the dynamic allocation of a mobile fraction of light-harvesting complex II (LHCII) to photosystem II (PSII) in state I and to photosystem I (PSI) in state II. In the state I-to-state II transition, LHCII is phosphorylated by STN7 and associates with PSI to favor absorption cross-section of PSI. Here, we used Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutants with defects in chlorophyll (Chl) b biosynthesis or in the chloroplast signal recognition particle (cpSRP) machinery to study the flexible formation of PS-LHC supercomplexes. Intriguingly, we found that impaired Chl b biosynthesis in chlorina1-2 (ch1-2) led to preferentially stabilized LHCI rather than LHCII, while the contents of both LHCI and LHCII were equally depressed in the cpSRP43-deficient mutant (chaos). In view of recent findings on the modified state transitions in LHCI-deficient mutants (Benson et al., 2015), the ch1-2 and chaos mutants were used to assess the influence of varying LHCI/LHCII antenna size on state transitions. Under state II conditions, LHCII-PSI supercomplexes were not formed in both ch1-2 and chaos plants. LHCII phosphorylation was drastically reduced in ch1-2, and the inactivation of STN7 correlates with the lack of state transitions. In contrast, phosphorylated LHCII in chaos was observed to be exclusively associated with PSII complexes, indicating a lack of mobile LHCII in chaos. Thus, the comparative analysis of ch1-2 and chaos mutants provides new evidence for the flexible organization of LHCs and enhances our understanding of the reversible allocation of LHCII to the two photosystems.

In oxygenic photosynthesis, PSII and PSI function in series to convert light energy into the chemical energy that fuels multiple metabolic processes. Most of this light energy is captured by the chlorophyll (Chl) and carotenoid pigments in the light-harvesting antenna complexes (LHCs) that are peripherally associated with the core complexes of both photosystems (Wobbe et al., 2016). However, since the two photosystems exhibit different absorption spectra (Nelson and Yocum, 2006; Nield and Barber, 2006; Qin et al., 2015), PSI or PSII is preferentially excited under naturally fluctuating light intensities and qualities. To optimize photosynthetic electron transfer, the excitation state of the two photosystems must be rebalanced in response to changes in lighting conditions. To achieve this, higher plants and green algae require rapid and precise acclimatory mechanisms to adjust the relative absorption cross-sections of the two photosystems.

To date, the phenomenon of state transitions is one of the well-documented short-term acclimatory mechanisms. It allows a mobile portion of the light-harvesting antenna complex II (LHCII) to be allocated to either photosystem, depending on the spectral composition and intensity of the ambient light (Allen and Forsberg, 2001; Rochaix, 2011; Goldschmidt-Clermont and Bassi, 2015; Gollan et al., 2015). State transitions are driven by the redox state of the plastoquinone (PQ) pool (Vener et al., 1997; Zito et al., 1999). When PSI is preferentially excited (by far-red light), the PQ pool is oxidized and all the LHCII is associated with PSII. This allocation of antenna complexes is defined as state I. When light conditions (blue/red light or low light) favor exciton trapping of PSII, the transition from state I to state II occurs. The over-reduced PQ pool triggers the activation of the membrane-localized Ser-Thr kinase STN7, which phosphorylates an N-terminal Thr on each of two major LHCII proteins, LHCB1 and LHCB2 (Allen, 1992; Bellafiore et al., 2005; Shapiguzov et al., 2016). Phosphorylation of LHCII results in the dissociation of LHCII from PSII and triggers its reversible relocation to PSI (Allen, 1992; Rochaix, 2011). Conversely, when the PQ pool is reoxidized, STN7 is inactivated and the constitutively active, thylakoid-associated phosphatase TAP38/PPH1 dephosphorylates LHCII, which then reassociates with PSII (Pribil et al., 2010; Shapiguzov et al., 2010). The physiological significance of state transitions has been demonstrated by the reduction in growth rate seen in the stn7 knock-out mutant under fluctuating light conditions (Bellafiore et al., 2005; Tikkanen et al., 2010).

The canonical state transitions model implies spatial and temporal regulation of the allocation of LHC between the two spatially segregated photosystems (Dekker and Boekema, 2005). PSII-LHCII supercomplexes are organized in a tightly packed form in the stacked grana regions of thylakoid membranes, while PSI-LHCI supercomplexes are mainly localized in the nonstacked stromal lamellae and grana margin regions (Dekker and Boekema, 2005; Haferkamp et al., 2010). It has been proposed that, in the grana margin regions, which harbor LHCII and both photosystems, LHCII can migrate rapidly between them (Albertsson et al., 1990; Albertsson, 2001). This idea is supported by the recent discovery of mega complexes containing both photosystems in the grana margin regions (Yokono et al., 2015). Furthermore, phosphorylation of LHCII was found to increase not only the amount of PSI found in the grana margin region of thylakoid membranes (Tikkanen et al., 2008a), but also to modulate the pattern of PSI-PSII megacomplexes under changing light conditions (Suorsa et al., 2015). Nonetheless, open questions remain in relation to the physiological significance of the detection of phosphorylated LHCII in all thylakoid regions, even under the constant light conditions (Grieco et al., 2012; Leoni et al., 2013; Wientjes et al., 2013), although LHCII phosphorylation has been shown to modify the stacking of thylakoid membranes (Chuartzman et al., 2008; Pietrzykowska et al., 2014).

State I-to-state II transition is featured by the formation of LHCII-PSI-LHCI supercomplexes, in which LHCII favors the light-harvesting capacity of PSI. Recently, LHCII-PSI-LHCI supercomplexes have been successfully isolated and purified using various detergents (Galka et al., 2012; Drop et al., 2014; Crepin and Caffarri, 2015) or a styrene-maleic acid copolymer (Bell et al., 2015). These findings yielded further insights into the reorganization of supercomplexes associated with state transitions, and it was suggested that phosphorylation of LHCB2 rather than LHCB1 is the essential trigger for the formation of state transition supercomplexes (Leoni et al., 2013; Pietrzykowska et al., 2014; Crepin and Caffarri, 2015; Longoni et al., 2015). Furthermore, characterization of mutants deficient in individual PSI core subunits indicates that PsaH, L, and I are required for docking of LHCII at PSI (Lunde et al., 2000; Zhang and Scheller, 2004; Kouril et al., 2005; Plöchinger et al., 2016).

Recently, the state transition capacity has been characterized in the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutants with missing LHCI components. Although the Arabidopsis knock-out mutants lacking one of the four LHCI proteins (LHCA1-4) showed enhanced accumulation of LHCII-PSI complexes, the absorption cross-section of PSI under state II conditions was still compromised in the lhca1-4 mutants, and it is suggested that LHCI mediates the detergent-sensitive interaction between ‘extra LHCII’ and PSI (Benson et al., 2015; Grieco et al., 2015). Furthermore, the Arabidopsis mutant ΔLhca lacking all LHCA1-4 proteins was shown to be compensated for the deficiency of LHCI by binding LHCII under state II conditions (Bressan et al., 2016). In spite of this finding, the significant reduction in the absorption cross-section of PSI was still observed in the ΔLhca mutant, suggesting a substantial role of LHCI in light absorption under canopy conditions (Bressan et al., 2016). However, these findings emphasize the acclimatory function of state transitions in balancing light absorption capacity between the two photosystems by modifying their relative antenna size and imply the dynamic and variable organization of PS-LHC supercomplexes.

LHC proteins are encoded by the nuclear Lhc superfamily (Jansson, 1994). The biogenesis of LHCs includes the cytoplasmic synthesis of the LHC precursor proteins, their translocation into chloroplasts via the TOC/TIC complex, and their posttranslational targeting and integration into the thylakoid membranes by means of the chloroplast signal recognition particle (cpSRP) machinery (Jarvis and Lopez-Juez, 2013). The posttranslational cpSRP-dependent pathway for the final translocation of LHC proteins into the thylakoid membrane includes interaction of cpSRP43 with LHC apo-proteins and recruitment of cpSRP54 to form a transit complex. Then binding of this tripartite cpSRP transit complex to the SRP receptor cpFtsY follows, which supports docking of the transit complex to thylakoid membranes and its association with the LHC translocase ALB3. Ultimately, ALB3 inserts LHC apo-proteins into the thylakoid membrane (Richter et al., 2010). Importantly, stoichiometric amounts of newly synthesized Chl a and Chl b as well as carotenoid are inserted into the LHC apo-proteins by unknown mechanisms to form the functional LHCs that associate with the core complexes of both photosystems in the thylakoid membranes (Dall’Osto et al., 2015; Wang and Grimm, 2015).

The first committed steps in Chl synthesis occur in the Mg branch of the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis pathway. 5-Aminolevulinic acid synthesis provides the precursor for the formation of protoporphyrin IX, which is directed into the Mg branch (Tanaka and Tanaka, 2007; Brzezowski et al., 2015). Chl synthesis ends with the conversion of Chl a to Chl b catalyzed by Chl a oxygenase (CAO; Tanaka et al., 1998; Tomitani et al., 1999). It has been hypothesized that coordination between Chl synthesis and the posttranslational cpSRP pathway is a prerequisite for the efficient integration of Chls into LHC apo-proteins.

In this study, we intend to characterize the assembly of LHCs when the availability of Chl molecules or the integration of LHC apo-proteins into thylakoid membranes is limiting. To this end, we compared the assembly of LHCs and the organization of PS-LHC complexes in two different sets of Arabidopsis mutants. Firstly, we used the chlorina1-2 (ch1-2) mutant, which is defective in the CAO gene. The members of the second set of mutants carry knock-out mutations in genes involved in the chloroplast SRP pathway (Richter et al., 2010).

Our studies revealed distinct accumulation of PS-LHC supercomplexes between the two sets of mutant relative to wild-type plants. In spite of the defect in synthesis of Chl b, ch1-2 retains predominantly intact PSI-LHCI supercomplexes but has strongly reduced amounts of LHCII. In contrast, the chaos (cpSRP43) mutant exhibits synchronously reduced contents of both LHCI and LHCII, which results in the accumulation of PS core complexes without accompanying LHCs. Thus, the distribution of LHCs in the thylakoid membranes of the two mutants, ch1-2 and chaos, were explored under varying light conditions with the aim of elucidating the influence of modified LHCI/LHCII antenna size on state transitions. Our results contribute to an expanding view on the variety of photosynthetic complexes, which can be observed in Arabidopsis plants with specified mutations in LHC biogenesis.

RESULTS

Reduced Contents of LHCs in ch1-2 and cpsrp Mutants

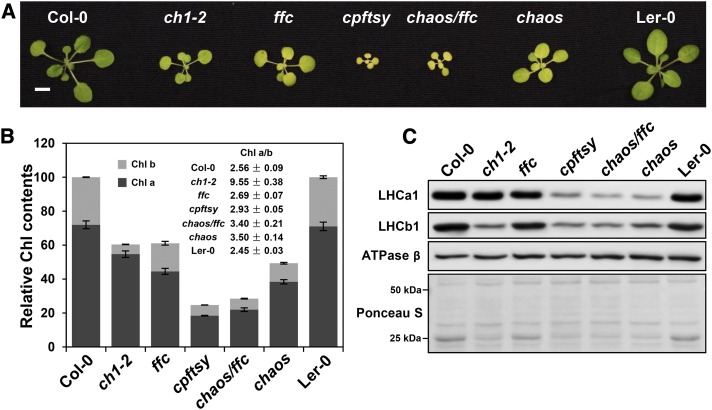

To examine the prerequisites for the precise reallocation of LHCII in response to an imbalance in the distribution of absorbed light energy between PSII and PSI, we examined mutants that are impaired in Chl b biosynthesis or in the cpSRP machinery. These mutants enable comparative studies on LHC accumulation during state transitions when the availability of either Chl b or LHC apo-proteins is limiting (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Characterization of Arabidopsis mutants with defects in Chl b biosynthesis and chloroplast SRP machinery. A, Representative photograph of an 18-d-old ch1-2 mutant and cpsrp mutants including chaos (cpsrp43), ffc (cpsrp54), the chaos/ffc (cpsrp43/cpsrp54) double mutant, and the cpftsy mutant and their corresponding wild-type progenitor plants (Ler-0 for chaos, Col-0 for all the others). Bar = 5 mm. B, Relative Chl contents and Chl a/b ratios in the above plants. The total Chl a + b levels in the wild-type plants were set to 100%. The data represent means ± sd of three biological replicates. C, Steady-state levels of LHC subunits (LCHA1 for LHCI and LHCB1 for LHCII) and the ATPase β-subunit in the thylakoid membranes from the above plants were analyzed by immunoblotting. An equivalent of 1.5 μg of Chl was loaded on the 12% SDS-urea-PA gel. Equality of loading was monitored by the level of the ATPase β-subunit and by Ponceau red staining (Ponceau S). Three biological replicates were performed, and similar results were obtained.

Three allelic Arabidopsis cao mutants have been reported and termed chlorina1-1, 1-2, and 1-3 (ch1-1, ch1-2, and ch1-3). They either accumulate reduced amounts of Chl b or fail to synthesize it altogether and in turn show significantly reduced levels of LHC proteins (Murray and Kohorn, 1991; Espineda et al., 1999; Havaux et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009; Takabayashi et al., 2011). ch1-1 and ch1-3 entirely lack Chl b due to a CAO null mutation (Murray and Kohorn, 1991; Espineda et al., 1999; Havaux et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009; Takabayashi et al., 2011). In ch1-2, Chl b synthesis is compromised, and the CAO protein contains a V274E point mutation within its Rieske-binding domain (Espineda et al., 1999). In agreement with previous reports, the ch1-2 mutant accumulated only about 20% as much Chl b as the wild-type plants. As a result, the Chl a/b ratio in ch1-2 rises to about 9.55 (Fig. 1B).

Plants bearing knockout mutations in the nuclear genes encoding cpSRP43 (chaos; Amin et al., 1999; Klimyuk et al., 1999), cpSRP54 (ffc; Pilgrim et al., 1998; Amin et al., 1999), both cpSRP43 and cpSRP54 (chaos/ffc; Hutin et al., 2002), or cpFtsY (cpftsy; Tzvetkova-Chevolleau et al., 2007) always exhibited a pale-green leaf phenotype (Fig. 1A) and contained reduced Chl levels (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the alb3 mutant, which lacks the LHC translocase, shows an albino phenotype (Sundberg et al., 1997). Interestingly, in addition to chaos and ffc mutants, an additive effect on delayed plant growth and reduced Chl contents was found in chaos/ffc mutant (Fig. 1, A and B), highlighting the role of cpSRP43-cpSRP54 heterodimer in targeting of LHC proteins to thylakoid membranes. Moreover, the strongest pale-green phenotype and the most retarded plant growth were observed in the cpftsy mutants among the cpsrp mutants analyzed here (Fig. 1, A and B), indicating the indispensable function of cpFtsY in the cpSRP pathway.

In the mutants analyzed here, the LHC contents were examined by immunoblotting with antibodies raised against LHCA1 and LHCB1, as representative subunits of LHCI and LHCII, respectively. As shown before (Espineda et al., 1999), LHCB1 was strongly reduced in ch1-2 (Fig. 1C), while the LHCA1 content was unexpectedly slightly diminished (Fig. 1C). In contrast to ch1-2 mutant, the cpsrp mutants contained severely reduced contents of the LHCPs of both photosystems. Combining previous detailed descriptions of the effects of cpsrp mutations on levels of various LHCI and LHCII subunits (Pilgrim et al., 1998; Espineda et al., 1999; Hutin et al., 2002; Tzvetkova-Chevolleau et al., 2007; Ouyang et al., 2011), we concluded that, in each of the three cpsrp mutants studied here, steady-state amounts of LHCI and LHCII proteins are equally affected (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, levels of LHC proteins were clearly higher in ffc than in chaos, chaos/ffc, and cpftsy (Fig. 1C), indicating that cpSRP43 functions predominantly and independently from cpSRP54 in targeting of LHC proteins to the thylakoid membranes (Tzvetkova-Chevolleau et al., 2007; Liang et al., 2016). In summary, our initial results suggest that malfunction of the cpSRP pathway depresses steady-state levels of both LHCI and LHCII, while strongly reduced Chl b biosynthesis preferentially affects LHCII.

Accumulation of Photosynthetic Apparatus in ch1-2 and cpsrp Mutants

The diminished LHC contents observed in ch1-2 and cpsrp mutants enabled us to examine the consequences of each mutation for the assembly of PS-LHC complexes in the thylakoid membranes. For this purpose, the isolated thylakoid membranes were treated with the nonionic detergent n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (β-DM) to efficiently solubilize both grana and nonstacked regions (Jarvi et al., 2011; Grieco et al., 2015). The thylakoid membranes were then fractionated by large-pore Blue-Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (lpBN-PAGE) (Jarvi et al., 2011) followed by SDS-PAGE in the second dimension to determine the protein composition of each of the various photosynthetic complexes.

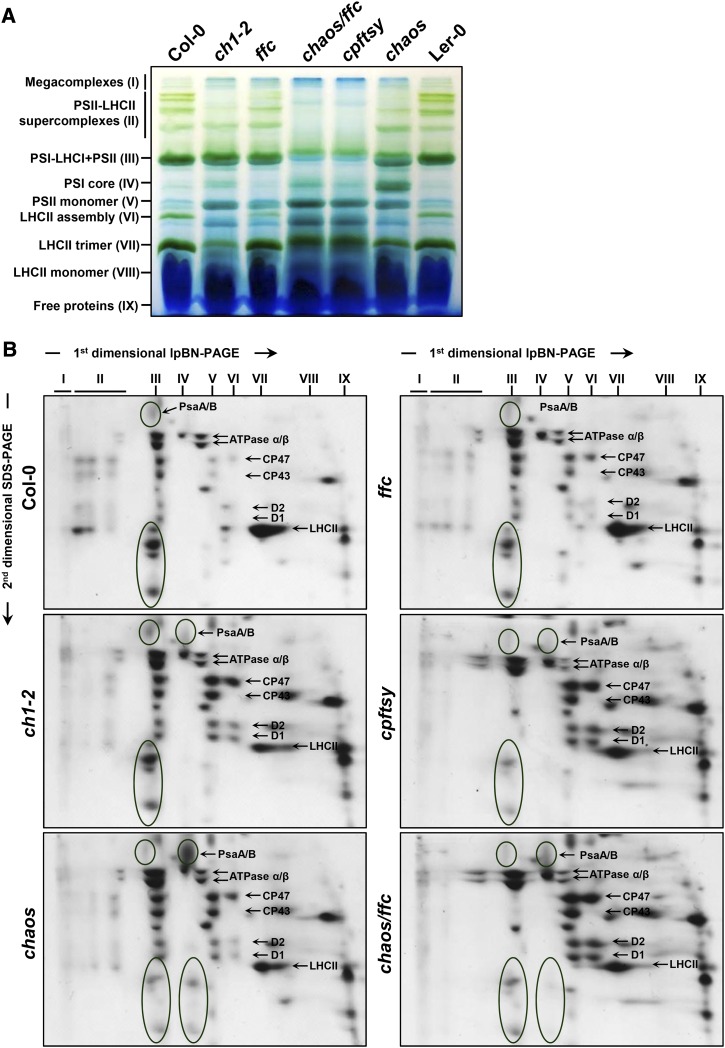

In the thylakoid membranes, LHCII is peripherally associated with PSII to form a PSII-LHCII supercomplex, which is mainly localized in the grana core regions (Dekker and Boekema, 2005). Depending on the binding strength of LHCII to PSII, four variants of PSII-LHCII supercomplexes (II) were observed on the lpBN-PA gel (Fig. 2, A and B). Apart from the PSII-LHCII supercomplexes, several PSII subcomplexes, including the PSII dimer (III), PSII monomer (V), LHCII assembly complex (VI), trimeric and monomeric LHCII (VII and VIII) could be detected (Fig. 2, A and B), which is consistent with previous reports (Jarvi et al., 2011). The ch1-2, ffc, and chaos mutants were characterized by reduced amounts of the PSII-LHCII supercomplexes and LHCII trimers, which are in turn associated with elevated levels of the PSII monomer and LHCII assembly complex (Fig. 2, A and B). The chaos/ffc and cpftsy mutants showed a more severe reduction in PSII-LHCII supercomplexes and PSII dimers (Fig. 2, A and B), suggesting that simultaneous loss of cpSRP43 and cpSRP54 or deficiency of the cpFtsY receptor affects not only the stability of antenna proteins but also the assembly of the PSII core complex in the thylakoid membranes. This observation is supported by the earlier finding that cpSRP54 and cpFtsY cooperate in the cotranslational integration of plastid-encoded PSII core subunits (Richter et al., 2010).

Figure 2.

Analyses of thylakoid membrane pigment-protein complexes. A, Equal amounts of thylakoid membranes (8 μg of Chl) from wild-type plants (Col-0 and Ler-0), ch1-2 and cpsrp mutant plants were solubilized with 1% (w/v) DM and first separated by lpBN-PAGE. B, Individual lanes from the lpBN-PAGE gel in A were then subjected to SDS-urea-PAGE in the second dimension. Total proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Identities of the relevant proteins are indicated by arrows. The major PSI proteins, PsaA/B, as well as minor proteins are circled. Two biological replicates were performed, and similar results were obtained.

In contrast to the various PSII-LHCII supercomplexes seen in wild-type plants, only a single PSI-LHCI supercomplex (III) was observed in control plants, which migrates close to PSII dimers on lpBN-PA gels. In mutants defective in LHCI formation, only PSI core complexes are observed (Havaux et al., 2007; Wientjes et al., 2009; Takabayashi et al., 2011; Benson et al., 2015). A dominant band of PSI core complexes was observed in the chaos mutant (Fig. 2, A and B), confirming reduced accumulation of LHCI subunits in chaos relative to ch1-2 (Fig. 1C). In addition to drastically disrupted assembly and/or reduced stability of PSII-LHCII supercomplexes and PSII dimers in chaos/ffc and cpftsy mutants, accumulation of both PSI-LHCI and PSI core complexes was strongly impaired (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast to these observations, the slight reductions in LHCI proteins seen in ch1-2 and ffc are consistent with a minor perturbation of PSI-LHCI supercomplex formation (Fig. 2, A and B).

In summary, based on the accumulation of PS-LHC complexes in the thylakoid membranes, ch1-2 and the different cpsrp mutants can be classified into three groups: (1) ch1-2 exhibited a drastically reduced content of LHCII and only a slightly impaired LHCI content; (2) chaos and ffc were both characterized by impaired accumulation of both LHCI and LHCII, with levels of both complexes being more severely affected in the chaos mutant than in ffc; and (3) the chaos/ffc and cpftsy mutants showed the greatest reductions in LHC content, and accumulated photosystem core complexes.

Impaired State Transitions in ch1-2 and cpsrp Mutants

Short-term state transitions enable the reversible allocation of LHCII to PSI when PSII rather than PSI is preferentially activated (Allen and Forsberg, 2001; Rochaix, 2011; Goldschmidt-Clermont and Bassi, 2015; Gollan et al., 2015). The observations that ch1-2 and chaos mutants exhibited distinct accumulation of PSI-LHCI complexes (Figs. 1 and 2) led to further exploration of the association of LHCII with PSI or PSII during state transitions. It was recently shown that an intact LHCI complex is required for a complete state I-to-state II transition (Benson et al., 2015). To explore these findings further, we compared state transitions in ch1-2 and chaos with control seedlings. We hypothesized that the defects in formation of PSI-LHCI supercomplexes observed in chaos would lead to an aberrant transition relative to ch1-2 and control plants under state II conditions (Figs. 1 and 2). As additional controls, we examined the ffc mutant, in which levels of both LHCs were only slightly reduced, and the stn7/8 double mutant. The latter mutant is unable to phosphorylate LHCII proteins and PSII core subunits and thus fails to undergo state transitions during changes in light quality.

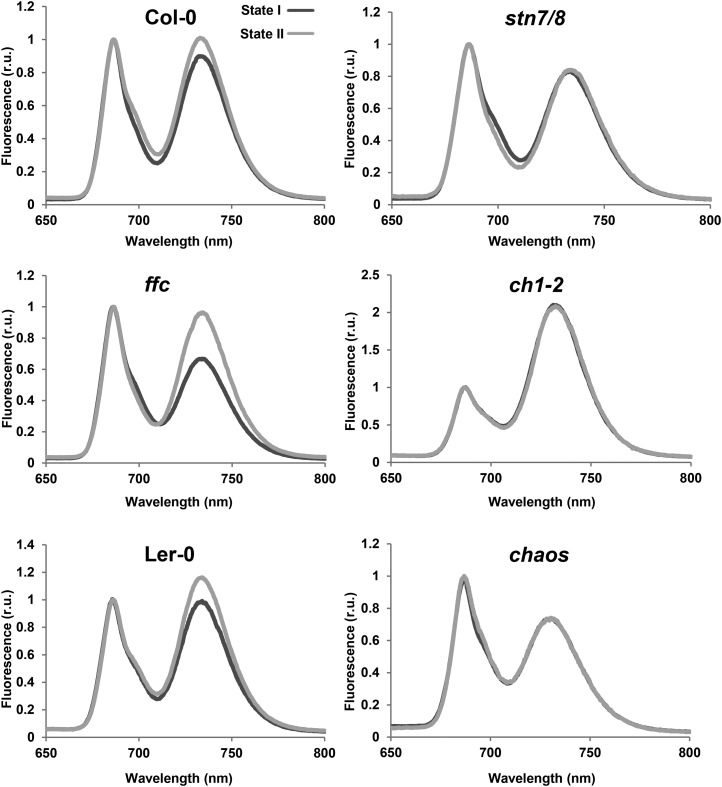

Light-dependent state transitions were marked by the allocation of LHCII to PSII in state I and its partial transfer to PSI in state II. Thus, modification of the antenna sizes (i.e. absorption cross-sections) of the photosystems, as determined by 77K fluorescence emission, reflected the capacity to undergo state transitions (Bellafiore et al., 2005; Tikkanen et al., 2008a). In wild-type plants, the transition from state I (induced by exposure to far-red light) to state II (upon exposure to red light) was accompanied by an obvious relative increase in PSI fluorescence emission at 733 nm, indicating the redistribution of excitation energy from PSII to PSI (Fig. 3). Although a slightly reduced content of LHCs was observed in the ffc mutant (Figs. 1 and 2), the PSI peak in ffc showed a greater enhancement under state II conditions than that in wild-type plants (Fig. 3). In contrast, the PSI fluorescence of ch1-2, chaos, and stn7/8 mutants showed no obvious increase under state II conditions (Fig. 3), implying that the state I-to-state II transition is blocked not only in stn7/8 but also in ch1-2 and chaos. The spectral response of the photosynthetic complexes in the thylakoids of chaos was consistent with a previous report (Pesaresi et al., 2009). Furthermore, it is worth noting that the PSII and PSI fluorescence peaks in ch1-2 differed by more than 2-fold (Fig. 3). This observation is explained by strongly impaired assembly of LHCII relative to the LHCI content at PSI in ch1-2 as a result of its deficiency in Chl synthesis. Apparently, LHCII assembly is far more susceptible to perturbation of Chl synthesis than formation of LHCI (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 3.

Analysis of state transitions by low-temperature (77K) fluorescence emission spectroscopy. Fluorescence emission spectra of thylakoid membranes were recorded at 77°K after exposure of wild-type plants (Col-0 and Ler-0) and the stn7/8, ch1-2, ffc, chaos mutants to lighting conditions that favor either state I (black lines, far-red light of 730 nm) or state II (gray lines, red light of 660 nm). The excitation wavelength was 475 nm, and spectra were normalized with reference to peak height at 685 nm. Three biological replicates were performed, and similar results were obtained.

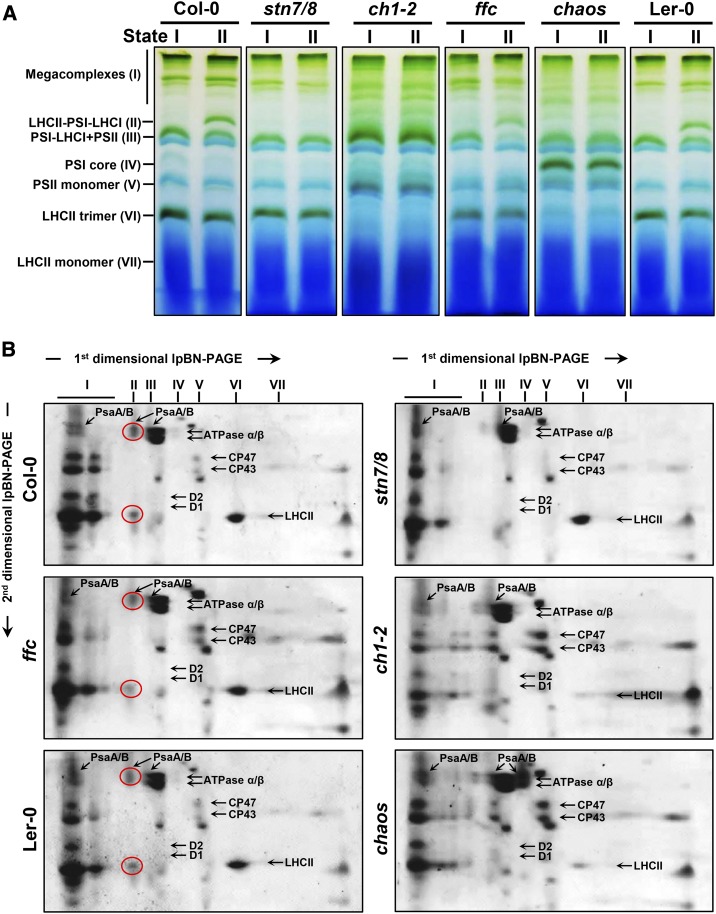

Next, the formation of the LHCII-PSI-LHCI supercomplexes under state II conditions was 2D lpBN-SDS-PAGE. To keep the LHCII-PSI-LHCI supercomplexes intact, the mild nonionic detergent digitonin was used instead of β-DM to specifically solubilize the nonappressed grana margins and stromal lamellae of thylakoid membranes (Järvi et al., 2011; Grieco et al., 2015). As expected, when plants were exposed to red light (state II), LHCII-PSI-LHCI supercomplexes were formed (Figs. 4), which raised the photochemical work rate of PSI (Galka et al., 2012). In agreement with 77K fluorescence emission spectra analysis (Fig. 3), LHCII-PSI-LHCI supercomplexes were observed only in wild-type plants and, to a lesser degree, in ffc under state II conditions (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, stn7/8, ch1-2, and chaos lacked these supercomplexes (Fig. 4, A and B). As shown in Figure 2, a stable PSI-LHCI complex was observed in ch1-2, while chaos accumulated PSI core complexes lacking LHCI (Fig. 4, A and B). Both ch1-2 and chaos mutants exhibited diminished levels of the LHCII trimer (Fig. 4, A and B). Nevertheless, megacomplexes containing PSI-LHCI and/or PSII-LHCII supercomplexes were still observed in all of the mutants analyzed under state II light (Fig. 4, A and B). Altogether, these results indicate ch1-2 and chaos mutants failed to perform state transitions and did not form LHCII-PSI-LHCI supercomplexes under state II conditions.

Figure 4.

Analysis of state transitions by lpBN-PA gel electrophoresis. A, Equal amounts of thylakoid membranes (9 μg of Chl) from wild-type plants (Col-0 and Ler-0) and the stn7/8, ch1-2, ffc, and chaos mutant plants, which had been adapted to state I light (far-red light of 730 nm) or state II light (the red light of 660 nm), were solubilized with 1% (w/v) digitonin and fractionated by lpBN-PAGE. B, Individual lanes from the lpBN-PA gel in A were then subjected to SDS-urea-PAGE in the second dimension. Total proteins were visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. Identities of the relevant proteins are indicated by arrows. The major PSI proteins, PsaA/B, as well as LHCII proteins in the LHCII-PSI-LHCII complexes are circled. Two biological replicates were performed, and similar results were obtained.

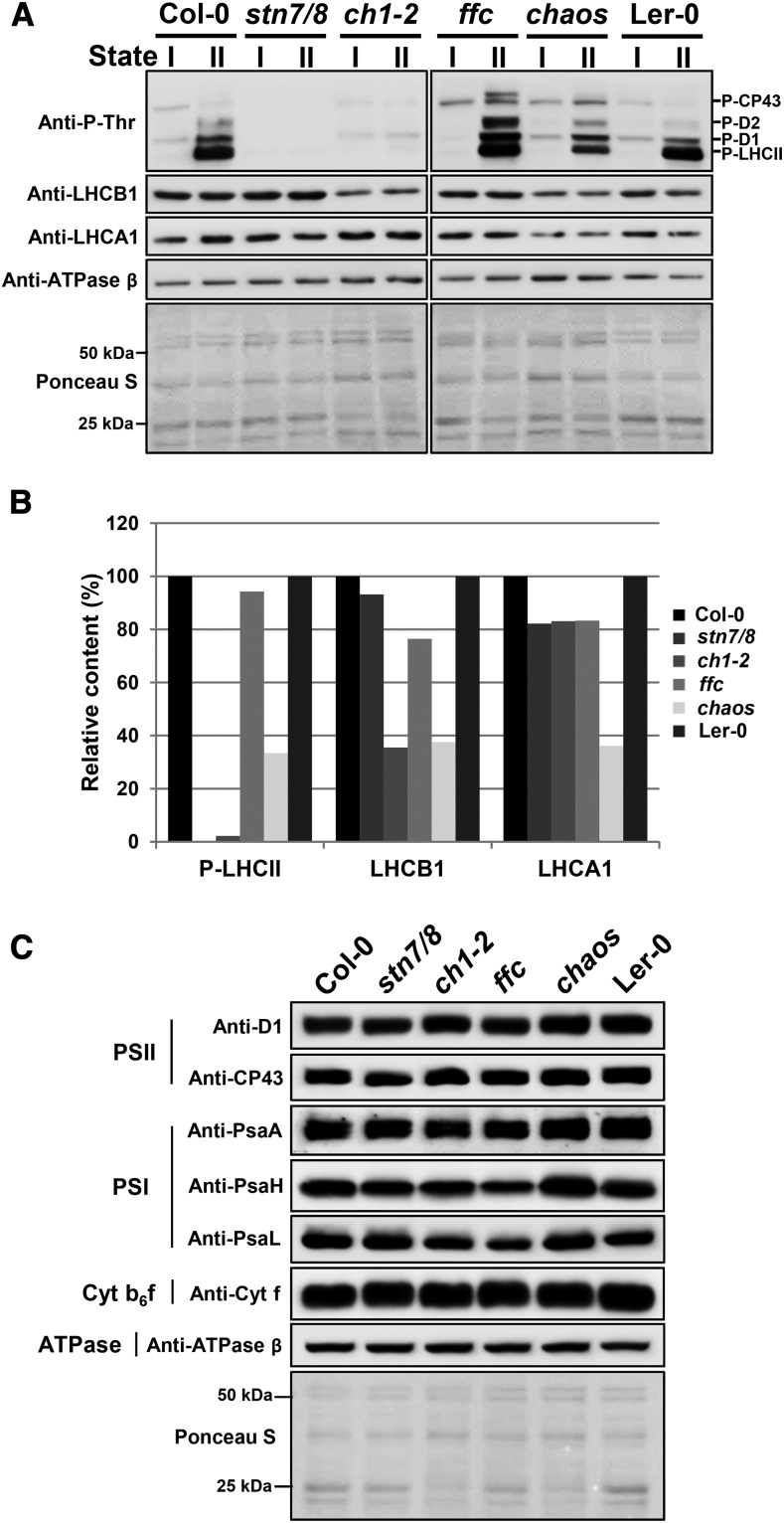

Phosphorylation of LHCII in ch1-2 and cpsrp Mutants

Phosphorylation of LHCII is reported to be a prerequisite for the state I-to-state II transition (Allen, 1992; Rochaix, 2011). The phosphorylation state of LHCII (P-LHCII), as well as of PSII core subunits (P-D1, P-D2, and P-CP43), was analyzed on a phospho-Thr immunoblot (Anti-P-Thr) when plants were acclimated to state I or state II light conditions. Both wild-type plants and the ffc mutant showed increased phosphorylation of LHCII and PSII core subunits in state II conditions, while P-LHCII and phosphorylated PSII core subunits were absent in both ch1-2 and stn7/8 mutants (Fig. 5A), implying that the kinases STN7 and STN8 are not activated in the ch1-2 mutant. Thus, it is suggested that the lack of state transition-dependent excitation energy transfer from LHCII to PSI in ch1-2 (Figs. 3 and 4) correlates with the lack of P-LHCII (Fig. 5A). It is worth mentioning that the content of phosphorylated PSII core subunits in the ffc mutant in state II conditions was higher than in the wild-type plants, which indicates that ffc is subjected to photoinhibition (Bonardi et al., 2005; Tikkanen et al., 2008b). In contrast, in the chaos mutant, P-LHCII was detected in state II conditions, but in lesser amounts than in Ler-0 plants (Fig. 5A). Semiquantitative analysis of the immunoblot in Figure 5A suggested that the LHCB1 level in chaos was highly correlated with the P-LHCII level (Fig. 5B). This finding implies that STN7 in chaos was activated to phosphorylate LHCII under state II conditions. However, no state transition was actually observed in the chaos mutant, which in this respect behaves like ch1-2 and stn7/8.

Figure 5.

Phosphorylation and steady-state levels of thylakoid proteins. A, Representative antiphospho-Thr (Anti-P-Thr) immunoblot showing the phosphorylation of the PSII core proteins (P-D1, P-D2, and P-CP43) and the LHCII (P-LHCII) proteins, and anti-LHCB1, anti-LHCA1, and anti-ATPase beta immunoblots showing the steady-state protein levels in the thylakoids of wild-type (Col-0 and Ler-0) and stn7/8, ch1-2, ffc, and chaos mutant plants, which were adapted to state I light (far-red light, 730 nm) or state II light (red light, 660 nm). Each sample contained 1 μg of Chl. To control for loading, the thylakoid proteins were stained with Ponceau red (Ponceau S). Three biological replicates were performed, and similar results were obtained. B, Immunoblots in A were analyzed with Phoretix 1D software (Phoretix International). The relative amounts of LHCB1 and LHCA1 were normalized to the level of the β-subunit of the ATP synthase (ATPase β). The relative phosphorylation level of the LHCII proteins was further normalized to the protein levels of LHCB1. Phosphorylation and protein levels in the mutant plants are shown relative to the levels in the wild-type plants (100%). C, Steady-state protein levels in the thylakoids of wild-type (Col-0 and Ler-0) as well as stn7/8, ch1-2, ffc, and chaos mutant plants, which were adapted to state II light (red light, 660 nm). Aliquots of 15 μg of total thylakoid proteins were loaded on the gels. Description of thylakoid membrane protein complexes and their diagnostic components are labeled on the left. Two biological replicates were performed, and similar results were obtained.

Protein Composition of Photosynthetic Complexes in ch1-2 and cpsrp Mutants

Although phosphorylation of LHCII occurred in the chaos mutant under state II conditions (Fig. 5), LHCII-PSI-LHCI supercomplexes were not detectable by BN gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4). It has been suggested that PsaH and PsaL serve as docking sites for P-LHCII in PSI (Lunde et al., 2000; Zhang and Scheller, 2004; Kouril et al., 2005). Thus, we hypothesized that the failure of chaos to form LHCII-PSI complexes might be due to impaired docking of P-LHCII at PSI. To test this possibility, we analyzed the accumulation of core subunits of four photosynthetic complexes, including D1 and CP43 subunits of the PSII complex; cytochrome f (Cyt f) of the Cyt b6f complex; PsaA, PsaH, and PsaL of the PSI complex; and the β-subunit of the ATP synthase in plants that were adapted to state II light conditions (Fig. 5C). We found increased PsaH and PsaL protein contents in chaos in comparison to wild-type plants (ecotype Ler-0), while the other proteins analyzed were not affected in chaos (Fig. 5C). These observations not only indicate that the docking site of P-LHCII at PSI is not affected in chaos but also prompted us to propose that cpSRP43 deficiency leads to a specific defect in the LHC biogenesis (Klimyuk et al., 1999; Hutin et al., 2002). Furthermore, we found reduced levels of plastid-encoded D1 and PsaA, and nuclear-encoded PsaH and PsaL in the ffc mutant (Fig. 5C). This finding supports previous results (Pilgrim et al., 1998; Amin et al., 1999), indicates the role of cpSRP54 in the biogenesis of plastid-encoded PS core subunits, such as D1 (Richter et al., 2010), and suggests an instability of PS core complexes in the ffc mutant.

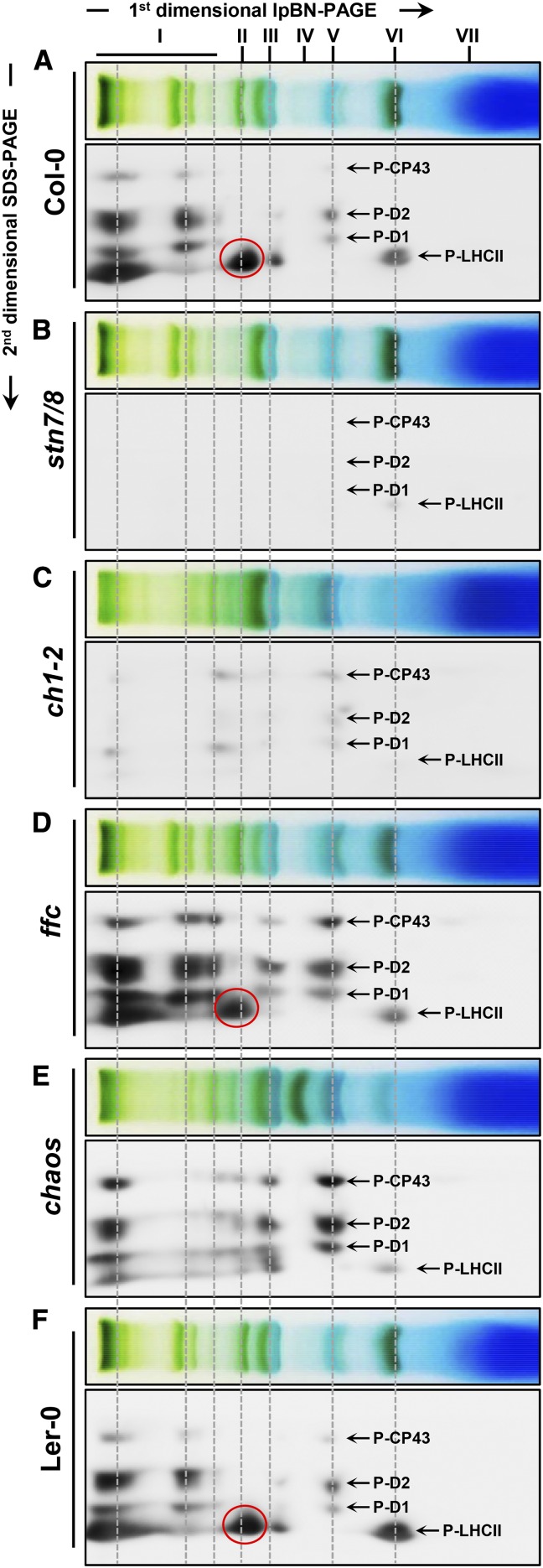

Distribution of Phosphorylated Proteins in the Thylakoid Membranes from ch1-2 and cpsrp Mutants

To address the distribution of P-LHCII in the grana margin regions of thylakoid membranes, thylakoid membranes adapted to state II conditions were isolated and solubilized with digitonin. The dominant photosynthetic pigment-protein complexes obtained were analyzed on 2D lpBN-SDS-PA gels. Phosphorylated LHCII and PSII core subunits were quantified by the phospho-Thr immunoblot. In agreement with a recent report (Grieco et al., 2015) and in contrast with stn7/8 (Fig. 6B), P-LHCII was not only found in LHCII-PSI-LHCI supercomplexes but also in the megacomplexes containing PSII-LHCII-PSI-LHCII and/or PSII-LHCII supercomplexes, dimeric and monomeric PSII complexes, and in LHCII trimers in both wild-type and ffc plants (Fig. 6, A, D, and F). Consistent with Figure 5A, very low levels of phosphorylated LHCII and PSII core subunits were detected in ch1-2 (Fig. 6C). Notably, since we found that P-LHCII exhibited the same migration rate on the lpBN-PAGE as P-D1, P-D2, and P-CP43 in the chaos mutant, we assume that P-LHCII is associated with PSII complexes rather than with the remaining PSI-LHCI complexes or PSI core complexes (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

Distribution of phosphorylated LHCII proteins and PSII core subunits in the thylakoid complexes. Equal amounts of thylakoid membranes (9 μg of Chl) from wild-type plants (Col-0, A and Ler-0, F) and stn7/8 (B), ch1-2 (C), ffc (D), and chaos (E) mutants, which had been adapted to state II light (red light, 660 nm), were solubilized with 1% (w/v) digitonin and separated by lpBN-PAGE. Individual lanes from the lpBN-PA gel were subjected to SDS-urea-PAGE in the second dimension, immunoblotted, and probed with an antiphospho-Thr antibody (Anti-P-Thr). The P-LHCII and PSII proteins (P-D1, P-D2, and P-CP43) were indicated by arrows. The proposed P-LHCII proteins associated with PSI-LHCI complexes are circled.

DISCUSSION

Diverse Accumulation of LHCI and LHCII When the Availability of Chl b or the Integration of LHC Apo-Proteins into Thylakoid Membranes Are Limiting

Integration of newly synthesized Chl a and Chl b into the LHC apo-proteins is essential for the stability, folding, and membrane insertion of functional LHCs and is a prerequisite for the association of LHCs with core complexes of two photosystems (Dall’Osto et al., 2015; Wang and Grimm, 2015). Thus, impaired synthesis of Chl and LHC apo-proteins, as well as dysfunctional posttranslational translocation of LHC apo-proteins from the cytosol to the chloroplasts by the TOC/TIC translocons and from the stroma to thylakoid membranes by the cpSRP machinery, could disrupt the association and assembly of LHCs in the thylakoids.

For the first time, to our knowledge, we have measured the accumulation of multiple PS-LHC supercomplexes and the allocation of phosphorylated LHCII to the two photosystems during state transitions in a Chl b-less mutant and cpsrp mutants (Figs. 1 and 2). It was expected that these mutants show the formation of different photosynthetic protein complexes with the intention to balance the excitation status of PSI and PSII. Lack of one or two components of cpSRP machinery, cpSRP43 and cpSRP54, caused simultaneously reduced levels of LHCI and LHCII (Fig. 1). In consequence, the comparatively strong decrease in LHCI and LHCII content in the chaos mutant led to accumulation of free PSI and PSII core complexes in place of the multiple PS-LHC complexes observed in wild-type chloroplasts (Figs. 1 and 2). These observations further support the idea that the cpSRP machinery acts nonselectively on the posttranslational targeting of LHCI and LHCII apo-proteins to thylakoid membranes (Richter et al., 2010).

In contrast, the ch1-2 mutant, which is defective in Chl b synthesis, exhibited rather stable LHCI complexes and wild-type-like PSI-LHCI supercomplexes, while LHCII content in ch1-2 was drastically reduced to a level comparable to that in chaos (Figs. 1 and 2). These observations are supported by the finding that the PSI antenna is larger than that of PSII in ch1-2 (Fig. 3).

Two possible explanations for the preferential stability of LHCI rather than of LHCII are proposed when availability of Chl b are limiting. Firstly, considering the varying specificity of LHCI and LHCII for Chl a and Chl b (Schmid, 2008), due to the enhanced promiscuity of LHCI, the Chl b-binding sites of LHCI proteins could be filled by Chl a when Chl b is in short supply. Indeed, in vitro reconstitution analyses have shown that Chl a can in fact be integrated into LHCI apo-proteins, such as LHCA2 and LHCA4, to form the stable LHCI (Schmid et al., 2002). Furthermore, the Chl a-containing LHCI has been characterized in the ch1-1 mutant, which lacks Chl b altogether (Havaux et al., 2007; Takabayashi et al., 2011). However, the Chl a-containing LHCI was less tightly associated with PSI core complexes, indicating Chl b is essential for the efficient energy transfer and stable assembly of PSI-LHCI supercomplexes (Takabayashi et al., 2011). Thus, the residual amount of Chl b in ch1-2 (20% of the wild-type level) might well be sufficient for the organization of functional PSI-LHCI supercomplexes (Figs. 1–3).

Secondly, we suggest that newly synthesized Chl b might be preferentially integrated into LHCI rather than LHCII, particularly when only limited amounts of Chl b are available. This hypothesis can be supported by our finding of the preferential accumulation of LHCI in ch1-2 (Figs. 1 and 2). So far, very little attention has been paid to the mechanisms that determine the distribution of newly synthesized Chl to the various LHC and PS-LHC complexes. What knowledge we do have is based on radioactive labeling with 14C. The radiolabeling experiments with Chl precursor molecules carried out on organisms exposed to high-light levels confirmed ongoing Chl synthesis in both higher plants (Beisel et al., 2010) and cyanobacteria (Kopecna et al., 2012). Interestingly, in the cyanobacteria, the freshly synthesized Chl was localized predominantly in PSI and to a lesser extent in PSII (Kopecna et al., 2012). In contrast, most of the fresh Chls produced in the chloroplasts of higher plants were suggested to support the PSII repair cycle, since PSI is very stable under high-light stress (Feierabend and Dehne, 1996). In this context, ch1-2 could be a useful tool for assessing the relative affinities of LHCI and LHCII for Chl b during their biogenesis.

Modified State Transitions Observed in ch1-2 and chaos Imply the Flexible Association of LHCs with Two Photosystems

To balance the excitation status of PSI and PSII, state transitions enable the rapid and efficient modification of the relative antenna size of the two photosystems in response to fluctuating light conditions (Allen and Forsberg, 2001; Rochaix, 2011; Goldschmidt-Clermont and Bassi, 2015; Gollan et al., 2015). In the state I-to-state II transition, phosphorylated LHCII proteins associate with PSI-LHCI to favor the absorption cross-section of PSI. However, increased absorption cross-section of PSI and formation of LHCII-PSI complexes were not detected in ch1-2 and chaos upon exposure to PSII-favoring light (Figs. 3 and 4), suggesting a block of the state I-to-state II transition in both ch1-2 and chaos mutants.

According to the canonical model of state transitions, phosphorylation of LHCII is an essential prerequisite for state I-to-state II transition and triggers the dissociation of LHCII from PSII and promotes its lateral migration to PSI-LHCI-enriched regions of thylakoid membranes (Allen, 1992; Rochaix, 2011). In this way, the missing formation of LHCII-PSI-LHCI complexes in ch1-2 is associated with the lack of P-LHCII under state II light conditions (Figs. 5A and 6C), which is explained by repression of STN7 activity. It is striking that in comparison with wild-type and cpsrp mutant plants, ch1-2 exhibited 2-fold larger antenna size of PSI than that of PSII (Fig. 3). In contrast, chaos exhibited the LHCII antenna similar to that in ch1-2 but less LHCI antenna (Figs. 1 and 2). This leads to the comparably balanced excitation state of PSI and PSII. The phosphorylation of LHCII was observed in chaos in the state II conditions (Figs. 5A and 6E), suggesting the more activated STN7 in chaos mutant than that in ch1-2 mutant. We assume that the electron transfer chain and the PQ pool were more oxidized in ch1-2 than in wild-type and chaos mutants. In turn, oxidation of PQ pool in ch1-2 will lead to inactivation of STN7.

As phosphorylation of LHCII is observed in chaos upon exposure to PSII light, balanced distribution of excitation energy between PSI and PSII is likely to be required under state II conditions. However, P-LHCII of chaos was associated with PSII complexes rather than with PSI core complexes or a residual amount of intact PSI-LHCI supercomplexes (Fig. 6E). The localization of P-LHCII could result from a failure to dissociate from PSII or an inability to dock at PSI. The latter prospect is challenged by the elevated accumulation of LHCII-PSI core complexes in the lhca4 mutant (Benson et al., 2015) and the ΔLhca mutant (Bressan et al., 2016), which were adapted to state II conditions. Structural studies of LHCII-PSI-LHCI complexes showed an opposite localization of P-LHCII and LHCI within the state-transition supercomplexes (Kouril et al., 2005; Drop et al., 2014). It is very unlikely that LHCI contributes to stable docking of LHCII at PSI complexes.

We propose that an impaired dissociation of P-LHCII from PSII results from a strongly reduced content of LHCII in chaos (Figs. 1 and 2). It is expected that a mobile P-LHCII pool is limited to migrate toward PSI complexes and form LHCII-PSI complexes. Although free phosphorylated LHCII trimers could be detected in chaos (Fig. 6E), the majority of LHCII trimers were associated with dimeric PSII core complexes (Figs. 2 and 4). According to the binding affinity of LHCII trimer to the PSII homodimer, S (strong), M (medium), and L (loose) variants of LHCII trimers were found in the thylakoid membranes of higher plants (Dekker and Boekema, 2005). It was indicated that the l-LHCII trimers could be associated with PSI, while the S-LHCII and M-LHCII are unlikely to be involved in state transitions (Pietrzykowska et al., 2014). Thus, the failure to form P-LHCII-PSI complexes in chaos is proposed to be due to the lack of a mobile LHCII pool.

In summary, the distinct accumulation of LHCI and LHCII complexes in ch1-2 and cpsrp mutants not only underlines the requirement for coordination of Chl biosynthesis and the posttranslational integration of LHC apo-proteins into thylakoid membranes (Dall’Osto et al., 2015; Wang and Grimm, 2015), but also indicates the variable accumulation of LHCI and LHCII complexes, when Chl b synthesis is compromised in ch1-2 mutant. Furthermore, the detailed comparative analysis of state transitions in ch1-2 and chaos mutants provides evidence for the flexible association of LHCs with the two photosystems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials, Growth Conditions, and Light Treatment

The following Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutants were used in this study: ch1-2, which contains a V274E mutation in the Rieske binding site (CS3120; Espineda et al., 1999), the maize Ds transposon-containing cpsrp43 mutant chaos (Klimyuk et al., 1999), the T-DNA insertion lines ffc (cpsrp54, CS850421; Pilgrim et al., 1998), cpftsy (SALK_049077; Tzvetkova-Chevolleau et al., 2007) and stn7/8 (Bonardi et al., 2005), and the chaos/ffc double mutant (Hutin et al., 2002), together with the wild-type Arabidopsis Col-0 and Ler-0. Wild-type and mutant Arabidopsis plants were routinely grown at 22°C and 70% humidity with 100 μm photons m−2 s−1 on a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod.

Pigment Analysis

Chls were extracted from leaves with alkaline acetone (100% acetone:0.2 m NH4OH, 9:1) and analyzed using reversed-phase chromatography on an Agilent HPLC system as described (Schlicke et al., 2014).

Isolation of Thylakoid Membranes

Thylakoid membranes were isolated from Arabidopsis plants grown in well-controlled phytochambers or adapted to state I or state II conditions in the presence of 10 mm sodium fluoride NaF as described (Järvi et al., 2011). Chl concentration was determined as described (Wellburn, 1994).

77K Fluorescence Emission Spectroscopy

Freshly isolated thylakoids equivalent to 10 μg Chl mL−1 were resuspended in Chl fluorescence buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.8, 60% glycerol, 300 mm Suc, 5 mm MgCl2) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Chl a fluorescence emission was detected using a F-6500 fluorometer (Jasco). The sample was excited at a 475-nm wavelength. The emission spectra between 655 nm and 800 nm were recorded with a bandwidth of 10 nm.

Second Dimensional lpBN-SDS-PAGE

lpBN-PAGE was performed essentially according to Järvi et al. (2011). To comprehensively analyze the PSI-LHC supercomplexes present in grana and unstacked thylakoids, freshly isolated thylakoids equivalent to 0.5 μg Chl μL−1 were solubilized with 1% β-DM at 4°C for 5 min. To detect the LHCII-PSI-LHCI supercomplexes formed during state transitions, freshly isolated thylakoids were partially solubilized with 1% (w/v) digitonin at room temperature for 15 min. For the second dimensional SDS-PAGE analysis, the excised lpBN-PAGE lanes were soaked in SDS sample buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.002% bromophenol blue, and 50 mm DTT) for 0.5 h at room temperature and then layered onto 12% SDS-PAGE gels containing 6 m urea. The gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250 or used for immunoblot analyses.

Immunoblot Analyses

For immunoblot analysis, total thylakoid proteins normalized to equal Chl contents were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels containing 6 m urea. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare) and probed with specific antibodies directed against the light-harvesting antenna proteins LHCA1 and LHCB1 (Agrisera); the PSI core subunits D1 and CP43 (Agrisera); the Cyt b6f subunit Cyt f (Agrisera); the PSI core subunits PsaA, PsaH, and PsaL (Agrisera); the ATP synthase β-subunit (Agrisera); and phosphorylated thylakoid proteins (anti-P-Thr, New England Biolabs). Signals were detected with the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Danja Schünemann for all cpsrp mutants and discussion of impaired PSI-LHCI complexes in chaos mutant, and Dr. Dario Leister for the stn7/8 mutant.

Glossary

- Chl

chlorophyll

- cpSRP

chloroplast signal recognition particle

- LHC

light-harvesting complex

- lpBN

large-pore Blue-Native

- P-LHCII

phosphorylation state of LHCII

- PQ

plastoquinone

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (P.W.) and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft FOR2092 (grant no. GR 936/18-1 to B.G.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Albertsson P. (2001) A quantitative model of the domain structure of the photosynthetic membrane. Trends Plant Sci 6: 349–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertsson PA, Andreasson E, Svensson P (1990) The domain organization of the plant thylakoid membrane. FEBS Lett 273: 36–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JF. (1992) Protein phosphorylation in regulation of photosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1098: 275–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JF, Forsberg J (2001) Molecular recognition in thylakoid structure and function. Trends Plant Sci 6: 317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin P, Sy DA, Pilgrim ML, Parry DH, Nussaume L, Hoffman NE (1999) Arabidopsis mutants lacking the 43- and 54-kilodalton subunits of the chloroplast signal recognition particle have distinct phenotypes. Plant Physiol 121: 61–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisel KG, Jahnke S, Hofmann D, Köppchen S, Schurr U, Matsubara S (2010) Continuous turnover of carotenes and chlorophyll a in mature leaves of Arabidopsis revealed by 14CO2 pulse-chase labeling. Plant Physiol 152: 2188–2199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AJ, Frankel LK, Bricker TM (2015) High yield non-detergent isolation of photosystem i-light-harvesting chlorophyll II membranes from spinach thylakoids: implications for the organization of the PS I antennae in higher plants. J Biol Chem 290: 18429–18437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellafiore S, Barneche F, Peltier G, Rochaix JD (2005) State transitions and light adaptation require chloroplast thylakoid protein kinase STN7. Nature 433: 892–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson SL, Maheswaran P, Ware MA, Hunter CN, Horton P, Jansson S, Ruban AV, Johnson MP (2015) An intact light harvesting complex I antenna system is required for complete state transitions in Arabidopsis. Nat Plants 1: 15176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonardi V, Pesaresi P, Becker T, Schleiff E, Wagner R, Pfannschmidt T, Jahns P, Leister D (2005) Photosystem II core phosphorylation and photosynthetic acclimation require two different protein kinases. Nature 437: 1179–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressan M, Dall'Osto L, Bargigia I, Alcocer MJP, Viola D, Cerullo G, D'Andrea C, Bassi R, Ballottari M (2016) LHCII can substitute for LHCI as an antenna for photosystem I but with reduced light-harvesting capacity. Nat Plants 2: 16131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezowski P, Richter AS, Grimm B (2015) Regulation and function of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in plants and algae. Biochim Biophys Acta 1847: 968–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuartzman SG, Nevo R, Shimoni E, Charuvi D, Kiss V, Ohad I, Brumfeld V, Reich Z (2008) Thylakoid membrane remodeling during state transitions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20: 1029–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepin A, Caffarri S (2015) The specific localizations of phosphorylated Lhcb1 and Lhcb2 isoforms reveal the role of Lhcb2 in the formation of the PSI-LHCII supercomplex in Arabidopsis during state transitions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1847: 1539–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Osto L, Bressan M, Bassi R (2015) Biogenesis of light harvesting proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1847: 861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker JP, Boekema EJ (2005) Supramolecular organization of thylakoid membrane proteins in green plants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1706: 12–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drop B, Yadav K N S, Boekema EJ, Croce R (2014) Consequences of state transitions on the structural and functional organization of photosystem I in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J 78: 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espineda CE, Linford AS, Devine D, Brusslan JA (1999) The AtCAO gene, encoding chlorophyll a oxygenase, is required for chlorophyll b synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 10507–10511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feierabend J, Dehne S (1996) Fate of the porphyrin cofactors during the light-dependent turnover of catalase and of the photosystem II reactioncenter protein D1 in mature rye leaves. Planta 198: 413–422 [Google Scholar]

- Galka P, Santabarbara S, Khuong TT, Degand H, Morsomme P, Jennings RC, Boekema EJ, Caffarri S (2012) Functional analyses of the plant photosystem I-light-harvesting complex II supercomplex reveal that light-harvesting complex II loosely bound to photosystem II is a very efficient antenna for photosystem I in state II. Plant Cell 24: 2963–2978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt-Clermont M, Bassi R (2015) Sharing light between two photosystems: mechanism of state transitions. Curr Opin Plant Biol 25: 71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan PJ, Tikkanen M, Aro EM (2015) Photosynthetic light reactions: integral to chloroplast retrograde signalling. Curr Opin Plant Biol 27: 180–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco M, Suorsa M, Jajoo A, Tikkanen M, Aro EM (2015) Light-harvesting II antenna trimers connect energetically the entire photosynthetic machinery including both photosystems II and I. Biochim Biophys Acta 1847: 607–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco M, Tikkanen M, Paakkarinen V, Kangasjärvi S, Aro EM (2012) Steady-state phosphorylation of light-harvesting complex II proteins preserves photosystem I under fluctuating white light. Plant Physiol 160: 1896–1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haferkamp S, Haase W, Pascal AA, van Amerongen H, Kirchhoff H (2010) Efficient light harvesting by photosystem II requires an optimized protein packing density in grana thylakoids. J Biol Chem 285: 17020–17028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M, Dall’osto L, Bassi R (2007) Zeaxanthin has enhanced antioxidant capacity with respect to all other xanthophylls in Arabidopsis leaves and functions independent of binding to PSII antennae. Plant Physiol 145: 1506–1520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutin C, Havaux M, Carde JP, Kloppstech K, Meiherhoff K, Hoffman N, Nussaume L (2002) Double mutation cpSRP43--/cpSRP54-- is necessary to abolish the cpSRP pathway required for thylakoid targeting of the light-harvesting chlorophyll proteins. Plant J 29: 531–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson S. (1994) The light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1184: 1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järvi S, Suorsa M, Paakkarinen V, Aro EM (2011) Optimized native gel systems for separation of thylakoid protein complexes: novel super- and mega-complexes. Biochem J 439: 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis P, López-Juez E (2013) Biogenesis and homeostasis of chloroplasts and other plastids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14: 787–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EH, Li XP, Razeghifard R, Anderson JM, Niyogi KK, Pogson BJ, Chow WS (2009) The multiple roles of light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-protein complexes define structure and optimize function of Arabidopsis chloroplasts: a study using two chlorophyll b-less mutants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787: 973–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimyuk VI, Persello-Cartieaux F, Havaux M, Contard-David P, Schuenemann D, Meiherhoff K, Gouet P, Jones JD, Hoffman NE, Nussaume L (1999) A chromodomain protein encoded by the arabidopsis CAO gene is a plant-specific component of the chloroplast signal recognition particle pathway that is involved in LHCP targeting. Plant Cell 11: 87–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecná J, Komenda J, Bucinská L, Sobotka R (2012) Long-term acclimation of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 to high light is accompanied by an enhanced production of chlorophyll that is preferentially channeled to trimeric photosystem I. Plant Physiol 160: 2239–2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouril R, Zygadlo A, Arteni AA, de Wit CD, Dekker JP, Jensen PE, Scheller HV, Boekema EJ (2005) Structural characterization of a complex of photosystem I and light-harvesting complex II of Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochemistry 44: 10935–10940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoni C, Pietrzykowska M, Kiss AZ, Suorsa M, Ceci LR, Aro EM, Jansson S (2013) Very rapid phosphorylation kinetics suggest a unique role for Lhcb2 during state transitions in Arabidopsis. Plant J 76: 236–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang FC, Kroon G, McAvoy CZ, Chi C, Wright PE, Shan SO (2016) Conformational dynamics of a membrane protein chaperone enables spatially regulated substrate capture and release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: E1615–E1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longoni P, Douchi D, Cariti F, Fucile G, Goldschmidt-Clermont M (2015) Phosphorylation of the light-harvesting complex II isoform Lhcb2 is central to state transitions. Plant Physiol 169: 2874–2883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunde C, Jensen PE, Haldrup A, Knoetzel J, Scheller HV (2000) The PSI-H subunit of photosystem I is essential for state transitions in plant photosynthesis. Nature 408: 613–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DL, Kohorn BD (1991) Chloroplasts of Arabidopsis thaliana homozygous for the ch-1 locus lack chlorophyll b, lack stable LHCPII and have stacked thylakoids. Plant Mol Biol 16: 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson N, Yocum CF (2006) Structure and function of photosystems I and II. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57: 521–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nield J, Barber J (2006) Refinement of the structural model for the photosystem II supercomplex of higher plants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1757: 353–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang M, Li X, Ma J, Chi W, Xiao J, Zou M, Chen F, Lu C, Zhang L (2011) LTD is a protein required for sorting light-harvesting chlorophyll-binding proteins to the chloroplast SRP pathway. Nat Commun 2: 277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesaresi P, Hertle A, Pribil M, Kleine T, Wagner R, Strissel H, Ihnatowicz A, Bonardi V, Scharfenberg M, Schneider A et al. (2009) Arabidopsis STN7 kinase provides a link between short- and long-term photosynthetic acclimation. Plant Cell 21: 2402–2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzykowska M, Suorsa M, Semchonok DA, Tikkanen M, Boekema EJ, Aro EM, Jansson S (2014) The light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b binding proteins Lhcb1 and Lhcb2 play complementary roles during state transitions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26: 3646–3660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim ML, van Wijk KJ, Parry DH, Sy DA, Hoffman NE (1998) Expression of a dominant negative form of cpSRP54 inhibits chloroplast biogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J 13: 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plöchinger M, Torabi S, Rantala M, Tikkanen M, Suorsa M, Jensen PE, Aro EM, Meurer J (2016) The low molecular weight protein PsaI stabilizes the light-harvesting complex II docking site of photosystem I. Plant Physiol 172: 450–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribil M, Pesaresi P, Hertle A, Barbato R, Leister D (2010) Role of plastid protein phosphatase TAP38 in LHCII dephosphorylation and thylakoid electron flow. PLoS Biol 8: e1000288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X, Suga M, Kuang T, Shen JR (2015) Photosynthesis. Structural basis for energy transfer pathways in the plant PSI-LHCI supercomplex. Science 348: 989–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter CV, Bals T, Schünemann D (2010) Component interactions, regulation and mechanisms of chloroplast signal recognition particle-dependent protein transport. Eur J Cell Biol 89: 965–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochaix JD. (2011) Assembly of the photosynthetic apparatus. Plant Physiol 155: 1493–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicke H, Hartwig AS, Firtzlaff V, Richter AS, Glässer C, Maier K, Finkemeier I, Grimm B (2014) Induced deactivation of genes encoding chlorophyll biosynthesis enzymes disentangles tetrapyrrole-mediated retrograde signaling. Mol Plant 7: 1211–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid VH. (2008) Light-harvesting complexes of vascular plants. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 3619–3639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid VH, Potthast S, Wiener M, Bergauer V, Paulsen H, Storf S (2002) Pigment binding of photosystem I light-harvesting proteins. J Biol Chem 277: 37307–37314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiguzov A, Chai X, Fucile G, Longoni P, Zhang L, Rochaix JD (2016) Activation of the Stt7/STN7 kinase through dynamic interactions with the cytochrome b6f complex. Plant Physiol 171: 82–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiguzov A, Ingelsson B, Samol I, Andres C, Kessler F, Rochaix JD, Vener AV, Goldschmidt-Clermont M (2010) The PPH1 phosphatase is specifically involved in LHCII dephosphorylation and state transitions in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 4782–4787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg E, Slagter JG, Fridborg I, Cleary SP, Robinson C, Coupland G (1997) ALBINO3, an Arabidopsis nuclear gene essential for chloroplast differentiation, encodes a chloroplast protein that shows homology to proteins present in bacterial membranes and yeast mitochondria. Plant Cell 9: 717–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suorsa M, Rantala M, Mamedov F, Lespinasse M, Trotta A, Grieco M, Vuorio E, Tikkanen M, Järvi S, Aro EM (2015) Light acclimation involves dynamic re-organization of the pigment-protein megacomplexes in non-appressed thylakoid domains. Plant J 84: 360–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takabayashi A, Kurihara K, Kuwano M, Kasahara Y, Tanaka R, Tanaka A (2011) The oligomeric states of the photosystems and the light-harvesting complexes in the Chl b-less mutant. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 2103–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A, Ito H, Tanaka R, Tanaka NK, Yoshida K, Okada K (1998) Chlorophyll a oxygenase (CAO) is involved in chlorophyll b formation from chlorophyll a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 12719–12723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka R, Tanaka A (2007) Tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58: 321–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M, Grieco M, Kangasjärvi S, Aro EM (2010) Thylakoid protein phosphorylation in higher plant chloroplasts optimizes electron transfer under fluctuating light. Plant Physiol 152: 723–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M, Nurmi M, Kangasjärvi S, Aro EM (2008b) Core protein phosphorylation facilitates the repair of photodamaged photosystem II at high light. Biochim Biophys Acta 1777: 1432–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M, Nurmi M, Suorsa M, Danielsson R, Mamedov F, Styring S, Aro EM (2008a) Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of excitation energy distribution between the two photosystems in higher plants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1777: 425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomitani A, Okada K, Miyashita H, Matthijs HC, Ohno T, Tanaka A (1999) Chlorophyll b and phycobilins in the common ancestor of cyanobacteria and chloroplasts. Nature 400: 159–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzvetkova-Chevolleau T, Hutin C, Noël LD, Goforth R, Carde JP, Caffarri S, Sinning I, Groves M, Teulon JM, Hoffman NE, et al. (2007) Canonical signal recognition particle components can be bypassed for posttranslational protein targeting in chloroplasts. Plant Cell 19: 1635–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vener AV, van Kan PJ, Rich PR, Ohad I, Andersson B (1997) Plastoquinol at the quinol oxidation site of reduced cytochrome bf mediates signal transduction between light and protein phosphorylation: thylakoid protein kinase deactivation by a single-turnover flash. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 1585–1590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Grimm B (2015) Organization of chlorophyll biosynthesis and insertion of chlorophyll into the chlorophyll-binding proteins in chloroplasts. Photosynth Res 126: 189–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellburn AR. (1994) The spectral determination of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J Plant Physiol 144: 307–313 [Google Scholar]

- Wientjes E, Oostergetel GT, Jansson S, Boekema EJ, Croce R (2009) The role of Lhca complexes in the supramolecular organization of higher plant photosystem I. J Biol Chem 284: 7803–7810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wientjes E, van Amerongen H, Croce R (2013) LHCII is an antenna of both photosystems after long-term acclimation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1827: 420–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wobbe L, Bassi R, Kruse O (2016) Multi-level light capture control in plants and green algae. Trends Plant Sci 21: 55–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokono M, Takabayashi A, Akimoto S, Tanaka A (2015) A megacomplex composed of both photosystem reaction centres in higher plants. Nat Commun 6: 6675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Scheller HV (2004) Light-harvesting complex II binds to several small subunits of photosystem I. J Biol Chem 279: 3180–3187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito F, Finazzi G, Delosme R, Nitschke W, Picot D, Wollman FA (1999) The Qo site of cytochrome b6f complexes controls the activation of the LHCII kinase. EMBO J 18: 2961–2969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]