ABSTRACT/Implementation Lessons

Engaging stakeholders in the research process has the potential to improve quality of care and the patient care experience.

Online patient community surveys can elicit important topic areas for comparative effectiveness research.

Stakeholder meetings with substantial patient representation, as well as representation from health care delivery systems and research funding agencies, are a valuable tool for selecting and refining pilot research and quality improvement projects.

Giving patient stakeholders a deciding vote in selecting pilot research topics helps ensure their ‘voice’ is heard.

Researchers and health care leaders should continue to develop best-practices and strategies for increasing patient involvement in comparative effectiveness and delivery science research.

Keywords: stakeholder engagement, diabetes, patient engagement, comparative effectiveness research

1. Background

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic health condition affecting more than 29 million people in the United States1. Diabetes has a profound negative impact on patient clinical outcomes and quality of life, and is costly to individual patients, their families, and society at large2–7. Diabetes poses enormous challenges for both individuals with diabetes and the health care system. Individuals and their caregivers must manage diet, exercise, medications, and self-monitoring on a daily basis8. In turn, the health care system must coordinate the efforts of multiple clinical disciplines to support patients and prevent serious and costly complications.

Comparative effectiveness research (CER) has the potential to improve the effectiveness and safety of diabetes care. The key goals of CER are to enhance the ability of patients, providers, delivery systems, and policy-makers to make evidence-based health care decisions, and to improve health care delivery and outcomes.9 Patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) is a type of CER that places a strong emphasis on input from a wide variety of health care stakeholders, especially patients, into research design, conduct, analysis, and translation.10 Many experts have suggested that PCOR’s emphasis on stakeholder input into the research process makes research more robust and relevant, and increases the wide-scale implementation of evidence-based findings into health care practice.10,11 The creation of the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) through the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 underscores the commitment of policy makers to involve patient stakeholders in PCOR10, and PCORI’s “Methodology Standards” specifically require that investigators provide evidence of patient involvement in creating research questions and appropriate study designs.12

Despite the call for increasing the involvement of patients and other stakeholders in the research process, there are very few specific guidelines or strategies for health care researchers developing plans to actively engage stakeholders in the research design process. Methods and best-practices for obtaining stakeholder guidance on shaping critical CER questions for improving patient care, particularly for diabetes and other chronic conditions, are largely unknown13. The purpose of this paper is to outline an evidence-based process for seeking input from patients and other stakeholders in shaping critical CER questions for diabetes. This process may provide a useful, replicable template for other researchers seeking to engage stakeholders in the CER design and implementation process.

2. Organizational Context

The SUrveillance PREvention and ManagEment of Diabetes Mellitus (SUPREME-DM) network was funded by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) from 2010–2013 through AHRQ’s “PRospective Outcome Systems using Patient-specific Electronic data to Compare Tests and therapies (PROSPECT)” initiative to develop and enhance CER data infrastructure and methods. The aims of the original SUPREME-DM study were to develop a multi-site data resource and investigator network for conducting high quality CER in diabetes14, and to leverage this data resource to conduct surveillance and CER studies. SUPREME-DM studies include efforts to better define the incidence and prevalence of diabetes in adults and youth15–18, assess temporal trends in diabetes complications, evaluate patterns of prescription medication use, initiation, intensification19–21, describe racial and ethnic disparities in care, evaluate quality measures22, examine pediatric diabetes care transitions, and advance CER methods for diabetes studies.23–26 SUPREME-DM also conducted an observational CER study comparing the effectiveness of different counseling and referral strategies for women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), and a cluster randomized CER trial of telephone outreach to improve adherence to newly-prescribed diabetes medications.

The SUPREME-DM CER data resource for conducting these studies is known as the DataLink, which includes a defined population of almost 1.3 million patients with diabetes across 11 HMO Research Network (HMORN) integrated health care delivery systems in the US14. The DataLink is a robust, geographically distributed research resource that combines patient demographic, health care utilization, diagnosis, procedure, medication, and laboratory data from EHR and other clinical and administrative databases. While the DataLink leverages diverse clinical data sources to advance CER in diabetes care and prevention, it currently includes few patient-reported outcomes (e.g. self-reported depression or diabetes distress measures are not available), and the studies conducted as part of the original SUPREME-DM grant were designed and implemented without input from stakeholders outside of the research team.

3. Personal Context

Kaiser Permanente (KP) Colorado is the lead site for the SUPREME-DM study, with John Steiner, MD, MPH, Senior Director of the KP Colorado Institute for Health Research, serving as Principal Investigator, and Andrea Paolino, MA serving as the study’s senior project manager. Dr. Steiner and Ms. Paolino worked closely with a subset of original SUPREME-DM research team members across 6 sites (Jay Desai, PhD, Emily Schroeder, MD PhD, Katherine Newton PhD, Jean Lawrence ScD MPH MSSA, Gregory Nichols PhD, Patrick O’Connor, MD MPH, and Julie Schmittdiel PhD) to develop and implement a strategy to enhance SUPREME-DM’s capabilities to conduct patient-centered CER in diabetes.

4. Challenge/Problem

In 2013, AHRQ released a ‘limited competition” Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) for grantees from PROSPECT and other large, AHRQ-funded CER research grants. This “Enhancing Investments in Comparative Effectiveness Research Resources” FOA called for proposals to use a stakeholder engagement process to “1) understand stakeholder needs in order to develop new comparative effectiveness research questions for which future research could fill important knowledge gaps and generate critical insights on the clinical effectiveness and comparative clinical effectiveness of health care interventions; 2) enhance the current data infrastructure and move towards sustainability through developing the ability to address these additional stakeholder-relevant questions.” The proposals were designed to fund primary data collection (including stakeholder input) and exploratory pilot projects, and were required to have a full project timeline no longer than 18 months.

Upon receiving an award through this mechanism in September 2013, our first challenge was to develop a stakeholder engagement process that would provide meaningful insight into the key patient-centered questions for diabetes CER. Our second challenge was to use this information to develop CER/PCOR pilot projects that would help enhance the SUPREME DM DataLink’s usefulness for conducting patient-centered research, and facilitate the DataLink’s long-term sustainability. We set out to create a strategy to include patients in outlining critical needs in CER/PCOR that was innovative, comprehensive, meaningful, and fast, and that would provide a template for patient stakeholder engagement that could be used by the SUPREME-DM research team and others in future research.

5. Solution

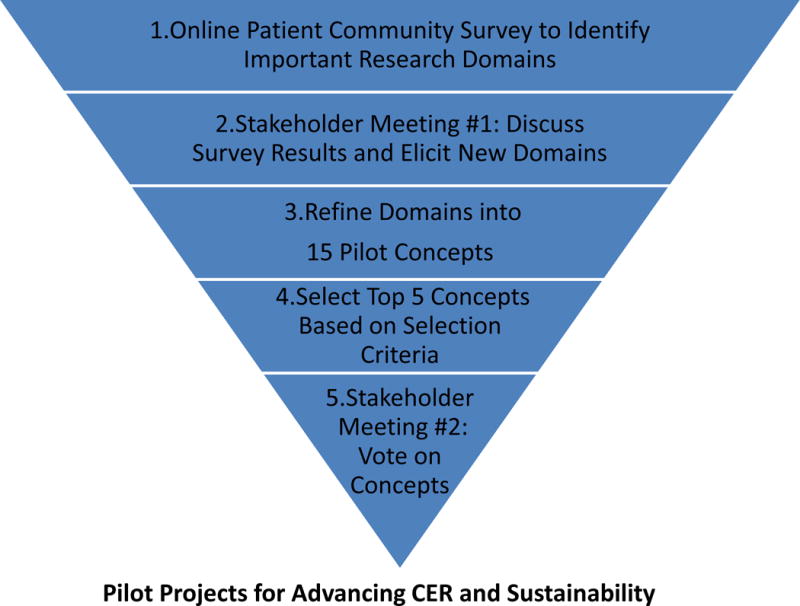

We developed a 5-step approach to engaging a diverse set of stakeholders to help us identify and prioritize CER questions that are most relevant to diabetes care and prevention, and guide the enhancement of the infrastructure and sustainability of the DataLink: a diagram outlining these steps is included as Figure 1. This participatory research-based process11 was modeled on five key principles of engaging a wide range of stakeholders in CER: ensuring balance among stakeholders; helping stakeholders understand their role in the process; providing neutral, expert facilitators for key discussions, and engaging participants throughout the research process.27 In addition, we sought to combine both qualitative and quantitative methods to gather stakeholder input.13 Our first step was to develop and administer an internet based survey of an online community of diabetes patients to identify key challenges in managing their diabetes. The second step was to conduct an in-person stakeholder meeting to assess what patients, clinicians, health care leaders, and policy-makers perceived as the critical knowledge gaps in diabetes, and needs for translating known evidence into optimal diabetes care. The research team then refined the domains obtained through the first two steps and used them to create 15 concepts for pilots to enhance the DataLink infrastructure for CER/PCOR (Step 3), and select 5 pilot concepts from this list based on pre-specified criteria (Step 4). In the fifth and final step, these 5 concepts were taken back to the stakeholders, who voted to determine which 3 pilots the SUPREME-DM research team would implement in the final phase of the process. Each of these five steps is described in detail below.

Figure 1.

Five Step Process to Design Pilots for Diabetes CER/PCOR Research

5a.Step 1: Online Patient Community Survey

We set out to ensure that the voices of patients figured prominently in our stakeholder engagement process by first conducting an online survey of individuals with diabetes to elicit patient-centered priorities for research in diabetes care. We believed that this broad-based approach was likely to identify a wide range of research priorities from a thoughtful and engaged group of individuals with diabetes. We selected this approach over more traditional first steps such as conducting focus groups with small numbers of individuals because we felt a quantitative approach would be more representative and likely to yield a greater number of ideas for discussion at the in-person stakeholder panel meeting.

To implement the survey, we collaborated with PatientsLikeMe® (PLM), a for-profit online platform and social network for individuals living with chronic conditions that offers tools for disease tracking, data sharing with peers, and the opportunity to participate in research studies.28 PLM facilitates virtual communities of over 200,000 individuals with a wide range of health conditions; more than 11,000 PLM members are self-identified as having diabetes. The SUPREME-DM team designed a survey that captured standard demographics and addressed patient experience in the key areas of: 1) getting diabetes care (e.g. ability to see specialists); 2) communication (e.g. shared decision making); 3) medication issues (e.g. insulin use); 4) lifestyle management (e.g physical activity); and 5) social engagement (e.g. social support). These domains were selected based on a scan of the literature, and through review of commonly-used domains in other large-scale surveys of diabetes patients (e.g. The Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)). In order to elicit patient preferences, questions were worded to assess how important each diabetes care and management issue was for the individual patient living with diabetes. Each topic domain was preceded by the prompt “We want to hear which questions about [domain heading] are most important to you right now. Please tell us which of these concerns about diabetes impacts you personally, and how difficult each one makes your life.” The five response options included: not difficult, a little difficult, somewhat difficult, very difficult, and does not apply. We also included open-ended questions to allow patients to further express their experiences and concerns living with diabetes. A final copy of this survey is included as an appendix.

PLM emailed survey invitations to its online community members that had previously self-identified as having diabetes in January 2014. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and patients were told that the results would be used to shape a CER research agenda for diabetes. The survey was ‘open’ for completion for 3 weeks; patients who did not respond to the initial invitation were sent up to two emailed reminders within 14 days. A total of 320 PLM members completed the survey (31% of the 1,044 who opened the email invitation); survey respondents were older, more likely to have Type 1 diabetes, and more likely to be female compared with non-respondents.

The KP Colorado Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined this survey did not fall under the jurisdiction of human subjects research since the work was hypothesis generating (i.e. not designed to test a hypothesis or answer a specific research question), and there was no collection or use of private, identifiable protected health information.

The de-identified responses to this online assessment were analyzed by the SUPREME-DM study team by reporting the range of responses for each question. Variation in responses was examined by key patient characteristics such as age, gender, employment status, health status, depression, and type of diabetes (type 1 vs. type 2). We presented a broad overview of these results to the full stakeholder panel meeting in Step 2.

Step 2: In-Person Stakeholder Meeting

We recruited a panel of stakeholders that included one representative from each of the organizations listed in Table 1. We sought the input of advocacy groups representing diabetes patients, clinicians, and stakeholders from the leadership of health systems that design and implement population-based care and prevention for diabetes. In addition, we included funders of CER as part of the stakeholders group, since they represented the perspective of those most likely to fund patient-centered PCOR projects in diabetes informed by this process. We also invited one government regulatory agency representative who was unable to attend.

Table 1.

Stakeholder Representation

| Federal Agencies |

| Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ) |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) |

| National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) |

| US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) |

| Membership/Advocacy Organizations |

| American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) |

| American Diabetes Association (ADA) |

| JDRF (formerly known as Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation) |

| Disadvantaged Populations |

| Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health, Colorado School of Public Health (University of Colorado at Denver) |

| Delivery Systems |

| Group Health Cooperative (GHC) |

| Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) |

| Patients |

| Five Individuals with Diabetes and One Family Member from the Kaiser Permanente Mid-Atlantic Region |

Since we considered people living with diabetes to be the most crucial stakeholders in determining the key questions for patient-centered CER in diabetes, we set a goal of recruiting 6–8 patients with diabetes to serve on the stakeholder group in order to help ensure a balance between patient perspectives and the perspectives of the organizational stakeholders. Adults with diabetes were selected from the membership of the Kaiser Permanente Mid-Atlantic Region (which encompasses Washington DC, Maryland and Northern Virginia) since the in-person stakeholder meeting was held in Washington DC.

A list of potential patient participants for the in-person stakeholder meeting was drawn from KP Member Voice (KPMV), an online panel of over 21,000 KP members nationwide who agree to be contacted for activities such as online surveys and focus groups. The project manager requested a list of KPMV panelists who were members of KPMA with a diagnosis of Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes; she requested a list with racial/ethnic representation that was equally balanced on gender.

The project manager called potential participants to assess their interest in being a stakeholder panelist and in actively participating in group discussions. As with the PLM work, the KPCO IRB determined that this patient involvement did not require IRB oversight, since the patients were engaged as stakeholders and not study subjects. Potential participants were told they would be paid $200 for the 8 hour in-person meeting and $50 for attending two webinars ($25 each) to be conducted after the meeting in Washington, DC, and that their travel costs would be reimbursed. Five individuals living with diabetes agreed to attend the in-person meeting; in addition, a spouse of one of the individuals with diabetes agreed to participate. Ultimately five individuals with diabetes and one family member comprised 6 of the 16 stakeholders on the panel (38%).

In order to prepare stakeholders for the discussion, we conducted two sets of stakeholder pre-meetings. Non-patient stakeholders attended an orientation Webinar in February 2014. This meeting was held twice (content and facilitator identical in each) in order to make attending as convenient as possible. This meeting provided an orientation to SUPREME-DM and the DataLink, and a description of CER/PCOR developed by PCORI and other experts9,29. This pre-meeting also reviewed the participatory research principles underlying our strategy for the stakeholder process11, and placed a specific emphasis on explaining the importance of incorporating patient opinions and priorities into the process. We strongly encouraged an atmosphere of listening and learning during the meeting.

The patients also received an orientation to the stakeholder meeting during a breakfast meeting on the morning of the stakeholder meeting, which provided an opportunity for the patients to meet each other and become familiar with the facilitator and the research team. We engaged in a discussion of the importance of including patient perspectives into the research process, emphasizing the critical value of their perspectives and encouraging them not to be intimidated by the organizational stakeholders in the room.

The six-hour meeting with the stakeholder panel and the research team was held at the Kaiser Permanente Center for Total Health in Washington DC on March 14, 2014. To ensure all stakeholders had equal opportunities to engage during the meeting, we enlisted a strong, experienced external meeting facilitator: Erin Holve, PhD, MPH, a Senior Director at AcademyHealth and principal investigator of the Electronic Data Methods (EDM) Forum grant from AHRQ30. The findings from the PLM survey were presented during this meeting to help spark conversation around patient priorities for diabetes care improvements and diabetes research. This presentation discussed the survey methods; described the survey population’s demographic and clinical characteristics; and presented patient-reported areas presenting care difficulties: results were shown as univariate distributions, and also stratified by Type 1 vs. Type 2 diabetes. Throughout the day, patient stakeholders were given the first opportunity to respond to questions that were raised, and patient responses were elicited by the meeting facilitator: the patient stakeholders participated actively in each portion of the meeting’s conversations. By encouraging the participation of all stakeholders, acting as an impartial mediator, and clarifying the proposals and options on each specific issue, the facilitator worked with the panel to reach consensus with all the stakeholders, including the patients, on a broad set of potential diabetes CER research topics, including a discussion about which of these topics could potentially translate into SUPREME-DM data infrastructure enhancements. Selected topics included pragmatic clinical trials, system-level studies, diabetes treatments (reasons for intensification, non-adherence, etc.), patient reported outcomes, patient education, and sustainability (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of Stakeholder Priority Diabetes CER Topics

| 1. | Studying clinical subgroups (phenotypes) |

| 2. | Increasing patient-guided treatment/shared decision-making |

| 3. | Improving/collecting information on care management approaches, coordination of care |

| 4. | Collecting information from patients via Interactive Voice Response (IVR) |

| 5. | Understanding patient and provider factors that play a role in intensification of diabetes treatment regimens |

| 6. | Developing pragmatic trials to improve diabetes care for the elderly and Type 1 DM |

| 7. | Targeting care to “high risk” individuals based on impairments in physical or mental health status (those in fair or poor health) |

| 8. | “Un-complicating” diabetes care through simplifying/coordinating medication regimens |

| 9. | Providing diabetes education and support in real-time through peers and/or professionals |

| 10. | Integrating clinical decision support into care and existing work flows |

| 11. | Developing valid, reliable data systems on diabetes education referral and follow-up |

| 12. | Assessing non-adherence as a potential ‘alert’/marker of diabetes distress |

Step 3: Refine Stakeholder Domains into 15 CER Pilot Projects

After the in-person meeting, the research team reviewed these high-priority diabetes CER topics in Table 2 to identify those that might be most suited for the SUPREME-DM data infrastructure, and/or potentially lead to improvements in the patient-centeredness of the SUPREME-DM data infrastructure, through development into pilot studies. The budget and timeline for the grant allowed for up to 3 pilot studies to be conducted between the end of the pilot selection process (at roughly the 9 month mark) and the end of the study (18 months). The research team members were asked to submit specific research pilot ideas within 3 weeks of the first stakeholder meeting, and briefly describe how pilot ideas were aligned with 6 pilot study selection criteria most consistent with the goals of the AHRQ FOA: innovation; feasibility/affordability; maximized use of the DataLink; patient-centeredness; potential for future funding (i.e. sustainability); and the likelihood that pilot findings could be published and lead to generalizable knowledge.

A total of 15 pilot research projects were submitted by the research team for initial consideration and ranking by the research team. The project manager distributed these concepts to the research team, who were asked to rate each pilot on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 being the best) on each of the 6 criteria listed above, and to provide an ‘overall’ score from 1 to 5 for each concept.

Step 4: Select Top 5 CER Pilot Project Concepts

On April 14, 2014 (one month after the stakeholder meeting), the research team held a meeting to review the 15 pilot ideas and their scores, and discuss which pilot concepts were the strongest candidates for pilot research studies. At the end of this meeting, the researchers selected the 5 pilot ideas that were most aligned with the selection criteria (including patient-centeredness) outlined above; the determination was based on the collective opinion of the research team. These potential studies were presented at the second stakeholder meeting described in Step 5 below.

Step 5: Stakeholder Meeting #2: Selecting the Final CER Pilot Projects

On May 7, 2014, each of the 5 top-ranking pilot ideas were presented to the stakeholders at a webinar-based meeting. Approximately 50% of the attendees present at the in-person meeting attended, including 50% of the patients. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss the extent to which the pilot ideas addressed the diabetes CER priorities gleaned from the initial stakeholder meeting, and to conduct rank voting on which 3 of the 5 should be approved and pursued in the second phase of the grant. This ‘rank voting’ approach to prioritization, which gave each stakeholder representative the opportunity to rank each project in a hierarchy on an ordinal 1–5 scale (with 1 being the highest priority and 5 being the lowest priority) is consistent with recommended methods for eliciting stakeholder preference endorsed by both PCORI and by AHRQ31,32. Only one round of rank voting was required to reach agreement on the top 3 prioritized projects; the 3 selected CER pilot projects based on this voting process are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Selected Diabetes CER Pilot Studies

| Pilot Research Project | Background | Key Aims | Importance to CER/PCOR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustaining the SUPREME- DM DataLink: Preliminary Data for Innovative Proposals | Because of its size, the SUPREME-DM database has large numbers of people in various subgroups. However, we have not fully explored the number of people in each subgroup and how well we can follow them over time. | 1. Organize existing data for key subgroups of interest (elderly, racial/ethnic subgroups, obesity, prediabetes), including documenting available length of follow- up. 2. Incorporate Stakeholder Priority 1 (Table 2) |

Funding requests require preliminary data and innovative ideas. These tables would show that we have the data available in this unique and comprehensive data set in order to answer CER/PCOR research priorities from the stakeholder group that can improve the lives of people living with diabetes or those who may develop it |

| Adding Self-Management and Healthy Lifestyle Counseling, Referrals, and Follow-Up Information to the SUPREME-DM Data Link | Diabetes education is an important aspect of diabetes treatment. We cannot currently measure diabetes education encounters (that is, when patients receive this education) in the SUPREME-DM data. | 1. Conduct interviews of health plan employees (clinicians, educators, health information technologists) to determine how diabetes education referrals and encounters are documented in the electronic medical record. Conduct chart reviews to see how accurate this information is. 2. Incorporate Stakeholder Priorities 9 and 11 (Table 2) |

An important first step for most studies of diabetes education is the ability to identify diabetes education encounters and referrals. Diabetes education was a key priority area for stakeholders. |

| Building a Patient- Centered Tool to Monitor Hypoglycemia Events | Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) symptoms and events are often not well captured in electronic medical records. | 1. Design a method of surveying people about how often they experience hypoglycemia and what their symptoms are. We could ask these questions by using interactive voice response (IVR) or text messaging. We would work together with focus groups of individuals living with diabetes to develop this system. 2. Incorporate Stakeholder Priorities 3,4,5 and 9 (Table 2) |

Hypoglycemia events can negatively effect people’s quality of life and impact treatment choices. Hypoglycemia is an important patient reported outcome for several potential funders. Collecting hypoglycemia information from patients via methods such as IVR and using it to better coordinate and improve care were priorities for our stakeholders. |

At the end of the webinar, the patient stakeholders gave the research team positive feedback on the extent to which they felt their voices were heard in the process. One patient said of the project ideas proposed, “It’s a good list.” Another patient said, “I think this is a good representation of what we discussed at the meeting in March. I feel that all areas have been covered, and I think it…stands out that the team has done an excellent job in breaking down the information and…meeting the needs of what needs to be done.” We also received positive feedback about the process overall, with patients telling us “It’s been a privilege and an honor to participate in this panel, and I would gladly do it again if asked,” and “Thank you for asking me to participate.”

6. Unresolved Questions and Lessons for the Field

The final step in our stakeholder engagement process will be to present the results from the 3 pilot research projects at the end of the study (March 2015), to share our findings, discuss plans for using the pilot results to pursue larger research projects, and obtain feedback on how to continue to develop the DataLink as a sustainable resource for diabetes CER/PCOR. In addition, we plan to continue our engagement with this stakeholder group by creating an ‘advisory board’ that can provide feedback on future research projects as they are developed.

Our hope is that these pilot projects shaped by patient and organizational stakeholder priorities will lead to research questions of interest to PCORI, AHRQ, NIDDK, and other agencies with a strong interest in stakeholder engagement. While we strongly believe that our investment in ongoing stakeholder engagement will lead to research that is more relevant to patients, and more likely to be implemented and disseminated by providers and health care delivery systems, we will need more time for this belief to be fully tested.

Our approach to assessing diabetes patient priorities and concerns through a broad-based online survey yielded a range of thought-provoking ideas that would likely not have emerged through in-person stakeholder meetings alone, and the findings from our survey significantly informed and enriched the stakeholder meeting process. This ‘hybrid’ process of combining in-person techniques with internet-based approaches combined the advantages of large sample sizes with in-depth engagement and perspectives33. While we believe that this hybrid approach is novel for diabetes research and care planning, and allows for a wide range of input, we acknowledge that there may still be limitations to the representativeness of the opinions that were gleaned from the stakeholders that were willing to participate in either the survey or the in-person meetings. While working with an online community may not be the only way of gathering a wide range of patient perspectives, we believe a broad-based assessment of the research domains relevant to patients is critical to formulating impactful questions in CER/PCOR. Other options for gathering this information might include conducting multiple semi-structured interviews; examining existing national survey sources, or publications documenting other stakeholder processes. Another important advantage of our particular process was the speed at which it could be completed: the entire process of prioritization and identification of the final ideas for pilot studies was completed within 6 months of the first research team project meeting.

Our project’s timeline and budget did not allow for a full evaluation of the impact of the stakeholder process on our outcomes, or of the perceptions of the process by the stakeholders themselves; this type of evaluation can be an important tool in understanding the overall effectiveness of stakeholder engagement34. However, as cited above our patient stakeholders did give us informal feedback that they were very satisfied with the process (see Section 5). In addition, our research team strongly believed that engaging stakeholders in designing comparative effectiveness research had a significant impact on the pilot research studies that will be conducted using the SUPREME-DM DataLink. For example, when we initially began our stakeholder process, there had been no discussion among the research team about pursuing research in diabetes education, or to adding variables about diabetes education classes and referrals to the DataLink (priorities 9 and 11 in Table 2). It was the direct input of our stakeholders (particularly our patient stakeholders) that prompted the research team to address this critical topic. In addition, the stakeholder input on the importance of gathering patient-reported information on hypoglycemia in ways that were convenient and acceptable to patients significantly shaped the pilot work in this area. These examples were important reminders that in order for research to truly address patient needs, researchers first need to go directly to the patients themselves to both assess and to better understand their concerns. CER/PCOR investigators should continue to work with providers and delivery systems to develop rapid, sustainable approaches to meaningfully involve patients in their efforts to develop patient-centered, learning health care systems.35–38

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding source:

This project was supported by grant numbers R01HS022963-01 and R01HS019859 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this work. Dr. Schmittdiel received additional support from the NIDDK-funded Health Delivery Systems Center for Diabetes Translational Research (1P30 DK92924)

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox CS, Coady S, Sorlie PD, et al. Increasing cardiovascular disease burden due to diabetes mellitus: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007 Mar 27;115(12):1544–1550. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.658948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franco OH, Steyerberg EW, Hu FB, Mackenbach J, Nusselder W. Associations of diabetes mellitus with total life expectancy and life expectancy with and without cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Jun 11;167(11):1145–1151. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodbard HW, Green AJ, Fox KM, Grandy S. Impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on prescription medication burden and out-of-pocket healthcare expenses. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010 Mar;87(3):360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Care. 2008 Mar;31(3):596–615. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang P, Brown MB, Bilik D, Ackermann RT, Li R, Herman WH. Health utility scores for people with type 2 diabetes in U.S. managed care health plans: results from Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Diabetes Care. 2012 Nov;35(11):2250–2256. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dall TM, Zhang Y, Chen YJ, Quick WW, Yang WG, Fogli J. The economic burden of diabetes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 Feb;29(2):297–303. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steiner JF. Rethinking adherence. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Oct 16;157(8):580–585. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine. Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. 2009 doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA. 2012 Apr 18;307(15):1583–1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmittdiel JA, Grumbach K, Selby JV. System-based participatory research in health care: an approach for sustainable translational research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2010 May-Jun;8(3):256–259. doi: 10.1370/afm.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The PCORI Methodology Report Appendix A: Methodology Standards. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guise JM, O’Haire C, McPheeters M, et al. A practice-based tool for engaging stakeholders in future research: a synthesis of current practices. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013 Jun;66(6):666–674. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nichols GA, Desai J, Elston Lafata J, et al. Construction of a multisite DataLink using electronic health records for the identification, surveillance, prevention, and management of diabetes mellitus: the SUPREME-DM project. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E110. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nichols GA, D J, Lawrence JM, Reid R, Schroeder EB, Steiner JF, Vupputuri S, Yan X, for the SUPREME-DM Study Group 5-Year incidence of diabetes among 6.7 million adult HMO members: The SUPRME-DM project. Diabetes. 2012;61(Suppl 1):A356. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nichols GA, D J, Lawrence JM, Reid R, Schroeder EB, Steiner JF, Vupputuri S, Yan X, for the SUPREME-DM Study Group Diabetes prevalence among 7 million adult HMO members, 2005–2009: The SUPREME-DM project. Diabetes. 2012;61(Suppl 1):A379. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence JM, D J, O’Connor PJ, Schroeder EB, Vupputuri S, Reid RJ, Steiner JF, Nichols GA, for the SUPREME-DM Study Group Use of Electronic Health Records to Estimate 5-Year Incidence of Diabetes among Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) Members < 20 Years of Age: The SUPREME-DM Project. Pediatric Diabetes. 2012;13(Suppl. 17):43–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence JM, O CP, Desai JR, Reid RJ, Schroeder E, Vupputuri S, Yan XS, Steiner J, Nichols GA, for the SUPREME-DM Study Group Diabetes Prevalence among 2.4 Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) Members < 20 years of Age, 2005–2009: The SUPREME-DM Project. Diabetologia. 2012;55(Suppl. 1):S152. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmittdiel JA, Raebel MA, Dyer W, et al. Prescription medication burden in patients with newly diagnosed diabetes: a SUrveillance, PREvention, and ManagEment of Diabetes Mellitus (SUPREME-DM) study. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2014 Jul-Aug;54(4):374–382. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.13195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raebel MA, Ellis JL, Schroeder EB, et al. Intensification of antihyperglycemic therapy among patients with incident diabetes: a SUrveillance PREvention and ManagEment of Diabetes Mellitus (SUPREME-DM) study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014 Jul;23(7):699–710. doi: 10.1002/pds.3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raebel MA, Xu S, Goodrich GK, et al. Initial antihyperglycemic drug therapy among 241 327 adults with newly identified diabetes from 2005 through 2010: a SUrveillance, PREvention, and ManagEment of Diabetes Mellitus (SUPREME-DM) study. Ann Pharmacother. 2013 Oct;47(10):1280–1291. doi: 10.1177/1060028013503624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmittdiel JA, R M, Dyer W, Steiner JF, Karter AJ, Nichols GA. The Medicare STAR adherence measure excludes patients with poor diabetes risk factor control. Am J Manag Care. 2014 in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raebel MA, Schmittdiel J, Karter AJ, Konieczny JL, Steiner JF. Standardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databases. Med Care. 2013 Aug;51(8 Suppl 3):S11–21. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829b1d2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schroeder EB, Goodrich GK, Newton KM, Schmittdiel JA, Raebel MA. Implications of different laboratory-based incident diabetic kidney disease definitions on comparative effectiveness studies. J Comp Eff Res. 2014 Jul;3(4):359–369. doi: 10.2217/cer.14.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hazlehurst BL, Lawrence JM, Donahoo WT, et al. Automating assessment of lifestyle counseling in electronic health records. Am J Prev Med. 2014 May;46(5):457–464. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu S, S EB, Shetterly S, Goodrich GK, O’Connor PJ, Steiner JF, Schmittdiel JA, Desai J, Pathak RD, Neugebauer R, Butler MG, Kirchner L, Raebel MA. Accuracy of hemoglobin A1c imputation using fasting plasma glucose in diabetes research using electronic health records data. Stat Optim Inf Comput. 2014 Jun;2:93–104. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffman A, Montgomery R, Aubry W, Tunis SR. How best to engage patients, doctors, and other stakeholders in designing comparative effectiveness studies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 Oct;29(10):1834–1841. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson ML, Bex PJ, Ellison JM, Wicks P, Wallis J. Feasibility of a web-based survey of hallucinations and assessment of visual function in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Interact J Med Res. 2014;3(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(PCORI) P-CORI. National Priorities for Research and Research Agenda. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holve E. Ensuring support for research and quality improvement (QI) networks: Four pillars of sustainability — an emerging framework. eGEMs (generating evidence & methods to improve patient outcomes) 2013;1(1) doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Haire C, McPheeters M, Nakamoto E, et al. Engaging Stakeholders To Identify and Prioritize Future Research Needs. Rockville (MD): 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleurence R, Selby JV, Odom-Walker K, et al. How the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is engaging patients and others in shaping its research agenda. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 Feb;32(2):393–400. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavallee DC, Wicks P, Alfonso Cristancho R, Mullins CD. Stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research: high-touch or high-tech? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014 Jun;14(3):335–344. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.901890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavallee DC, Williams CJ, Tambor ES, Deverka PA. Stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness research: how will we measure success? J Comp Eff Res. 2012 Sep;1(5):397–407. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen LA, Y MU, Wagner EH, Aiello Bowles EJ, Pardee R, Wellman R, et al. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary (IOM Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine) 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Etheredge LM. A rapid-learning health system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007 Mar-Apr;26(2):w107–118. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.w107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greene SM, Reid RJ, Larson EB. Implementing the learning health system: from concept to action. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Aug 7;157(3):207–210. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley WT, Glasgow RE, Etheredge L, Abernethy AP. Rapid, responsive, relevant (R3) research: a call for a rapid learning health research enterprise. Clin Transl Med. 2013;2(1):10. doi: 10.1186/2001-1326-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.