Abstract

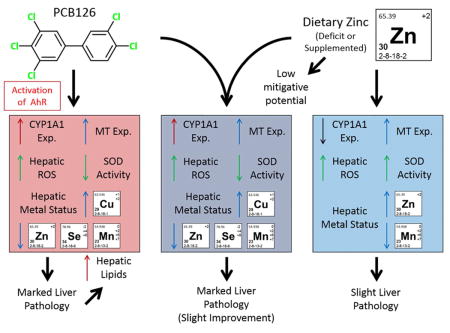

Hepatic levels of the essential micronutrient, zinc, are diminished by several hepatotoxicants, and the dietary supplementation of zinc has proven protective in those cases. 3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB126), a liver toxicant, alters hepatic nutrient homeostasis, and lowers hepatic zinc levels. The current study was designed to determine the mitigative potential of dietary zinc in the toxicity associated with PCB126 and the role of zinc in that toxicity. Male Sprague Dawley rats were divided into three dietary groups; fed diets deficient in zinc (7 ppm Zn), adequate in zinc (30 ppm Zn), and supplemented in zinc (300 ppm). The animals were maintained for 3 weeks on these diets, then given a single IP injection of vehicle or 1 or 5 μmol/kg PCB126. After two weeks, the animals were euthanized. Dietary zinc increased the level of ROS, the activity of CuZnSOD, and the expression of metallothionein, but decreased the levels of hepatic manganese. PCB126 exposed rats exhibited classic signs of exposure, including hepatomegaly, increased hepatic lipids, increased ROS and CYP induction. Liver histology suggests some mild ameliorative properties of both zinc deficiency and zinc supplementation. Other metrics of toxicity (relative liver and thymus weights, hepatic lipids, hepatic ROS) did not support this trend. Interestingly, the zinc supplemented – high dose PCB126 group had mildly improved histology and less efficacious induction of investigated genes than did the low dose PCB126 group. Overall, decreases in zinc caused by PCB126 likely contribute little to the ongoing toxicity and the mitigative/preventive capacity of zinc against PCB126 exposure seems limited.

TOC image

INTRODUCTION

Persistent environmental and industrial pollutants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), constitute an ongoing threat to human health with a perpetual exposure either through air or food.1, 2 The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) designates PCBs as group I human carcinogens, in addition to the substantial evidence of toxic effects on a wide range of organ systems.3 A specific PCB congener, 3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB126), is known for its persistence and potent toxicity to hepatic and immunological endpoints.4 This toxicity is mediated though the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) which regulates important genes in drug metabolism and antioxidant defenses.5 Recent studies have attempted to modulate the toxicity of PCB126 by co-opting a phenomenon associated with exposure, which is an alteration in hepatic trace elements.6, 7 These alterations are marked by decreases in hepatic selenium, manganese, and zinc and increases in copper. The extent of the contribution of these alterations to the ongoing toxicity is unknown. Studies using dietary supplementation of select micronutrients, in particular selenium and manganese, have shown some evidence of partial mitigation, however dietary zinc has not been evaluated.

Zinc is an essential micronutrient whose ability to abrogate hepatotoxicity has been well documented with such toxicants as carbon tetrachloride, acetaminophen, and ethanol along with hepatitis C.8–11 Zinc supplementation may impart its beneficial effects either by increasing the expression of an important family of metal transport and antioxidant proteins, metallothioneins, or by increasing the labile pool of zinc that can easily be accessed if needed.12, 13 The ease with which zinc supplementation could be used to offset the harmful effects of PCB exposure make it of great interest for use on highly exposed populations especially if promising results are garnered from a higher more acute dose investigated here.

It has been hypothesized that up to 12% of the American population are not adequately fulfilling their daily zinc requirement.14 The extent to which this mild/moderate zinc deficiency potentiates the effects of PCBs, thus creating a susceptible population, is not known. Zinc deficiency has been shown to increase the toxicity of several hepatotoxicants, including ethanol, carbon tetrachloride, and viral hepatitis.15–17 The essentiality of zinc, its role in critical metabolic processes, the decreases seen in hepatic levels after PCB126 exposure, and the ready availability of zinc as a dietary supplement support the investigation of zinc and its role in PCB126-mediated toxicity.

The usefulness of zinc supplementation as a therapy or preventive strategy for PCB exposure is unknown as is the effect of moderate zinc deficiency on PCB126 toxicity. The current study is designed to evaluate zinc supplementation in its ability to abrogate PCB126 morbidity and determine if moderate zinc deficiency aggravates PCB126 injury. In addition, the extent to which the changes in hepatic micronutrients associated with PCB126, specifically zinc, contributes to toxicity will also be learned. Given that zinc is such a vital micronutrient, the hypothesis of this study is that supplementation will decrease PCB126 toxicity whereas moderate zinc deficiency will result in increased damage. A better understanding of the role of zinc in PCB126 hepatotoxicity will also be elucidated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Chemicals and reagents used in these studies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. PCB126 synthesis was carried out using a Suzuki-coupling reaction of 3,4-dichlorophenyl boronic acid and 3,4,5-trichlorobenzene along with a palladium catalyst.18 Flash silica gel column chromatography and an aluminum oxide column were used to purify the final product followed by a recrystallization from methanol. Structure was confirmed with 13C NMR and the purity of the final product was >99.8% by GC/MS. Caution: Any handling of PCBs and their metabolites should be in accordance with those of hazardous compounds as set forth with NIH guidelines.

Animals

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Iowa approved all animal procedures and experimental designs described. 57 male Sprague-Dawley rats, 75–100 gram in weight, were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). The 4–5 week old animals were housed in wire hanging cages, one per cage, in a controlled environment of 22°C and a 12 hour light-dark cycle. Animals were then divided into three groups each fed a different diet. AIN-93G based diets with varying levels of zinc (7 ppm, 30 ppm, and 300 ppm), purchased from Harlan Tekland (Madison, WI), were provided ad libitum. The diet with the lower level of dietary zinc was chosen such that zinc was decreased significantly without resulting in deficiency-related toxicity, representing a mild to moderate zinc deficiency.19, 20 In addition, the adequate zinc level used, 30 ppm, is the set level found in the normal AIN-93G diet.21 In the diet, egg white solids were used as a protein source instead of casein to better control the level of dietary zinc. Animals were maintained on their respective diets for three weeks in order to ensure micronutrient equilibrium in all groups. A single IP injection of either vehicle (5 mL/kg body wt. tocopherol stripped soy oil; Harlan Tekland (Madison, WI)), vehicle with 1 μmol/kg PCB126 (low dose), or vehicle with 5 μmol/kg PCB126 (high dose) was administered. These doses/exposures were chosen based on previous studies investigating the hepatic effects of PCB126.4 Two weeks later, while maintained on their respective diets, the animals were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation followed by thoracotomy, and organs were weighed and either placed in 10% formalin or flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for later analysis.

Histology

Tissue pieces collected were placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for tissue fixation. Samples were routinely processed, embedded in paraffin and sectioned, using a microtome, to slices of 4 μm thickness. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). De-identified tissue samples were then diagnosed.

Lipid Extraction

Liver pieces weighing roughly 0.2 g were ground with diatomaceous earth using a mortar and pestle. Total extractable lipid extraction followed with chloroform:methanol (2:1 v/v) using an Accelerated Solvent Extractor (Dionex, Sunnvale, CA) as previously described.22 Concentrated samples were evaporated to dryness in pre-weighed vials and placed in a desiccator. Vials were weighed three times over several days, to constant weight and values normalized to tissue weight.

Gene Expression Determination

The assessment of the gene expression for select proteins was carried out using a two-step quantitative RT-PCR method. For isolation of total RNA from hepatic tissue, we employed a Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) RNeasy Mini kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions. A High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit from Applied Biosystems (Waltham, MA) converted the isolated RNA into Complimentary DNA using random primers. The real time RT-PCR used an Eppendorf Realplex Mastercycler with 10 ng cDNA, 300 nM primers, and Power Sybr Green PCR master mix from Applied Biosystems. Optimized reaction and two technical replicates were used. Actin served as the reference gene and the vehicle treated-adequate zinc diet animals functioned as the biological control. Table S1 in Appendix provides all primers used; primers were purchased from IDT (Coralville, IA).

ROS Determination

For the determination of hepatic ROS, we used an OxiSelect In Vitro ROS/RNS Assay Kit from Cell Biolabs (San Diego, CA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, liver pieces weighing between 10 and 20 mg were homogenized in PBS and diluted to a uniform concentration. Using a plate reader, the fluorescence in the samples, after adding the catalyst and a DCFH2 dye, were incubated for 45 minutes, after which the fluorescence was determined at 480 nm excitation/530 nm emission. Fluorescence was compared to a DCF standard curve. Values were adjusted and normalized to tissue weight.

SOD Activity Determination

Superoxide dismutase activity was determined using a competitive inhibition assay.23, 24 This assay measures the inhibition of superoxide-mediated nitroblue tetrazolium reduction (from xanthine/xanthine oxidase) spectrophotometrically at 560 nm and one unit is defined as that amount of protein capable of causing 50% of maximum inhibition (6–10 ng for pure CuZnSOD). Inhibition of CuZnSOD activity with 5 mM sodium cyanide was used to determine MnSOD activity. Activity was expressed as units/mg protein as determined by the method of Lowry as described previously.25, 26

Micronutrient Analysis

Hepatic and renal levels of zinc, copper, selenium, and manganese were determined using Inductively Coupled Plasma - Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Briefly, around 0.5 g of liver or kidney were weighed out and microwave-digested with 5 mL of trace metal grade nitric acid. Upon completion, 0.25 mL of trace metal grade hydrochloric acid was added and the volume brought up to 50 mL using reagent water (ASTM Type I). ICP-MS was used for determination of metal concentrations, specifically an Agilent 7500 ce ICP-MS equipped with a CETAC AS520 auto sampler was used. All results were normalized to tissue weight.

Statistics

Two-Way ANOVA analysis of the 3×3 experimental design was carried out using the Graphpad Prism 6 (v.6.05) software with a Tukey multiple comparison test to assess differences between groups. As noted in the figures, comparisons were made with the vehicle treatment within the same diet (notated with an *); in addition a comparison was made to the same treatment but in the adequate diet (notated with a #). P-values from two-way ANOVA are listed in Table S2. In addition, a multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis with interactions was carried out to assess overall differences and their directionality, i.e. increases or decreases. This was done using the proc reg function in SAS (v.9.3). These data are presented in Table 1. Given the large range for some endpoints, the values for CYP1A1, MTI, and MTII were log transformed after an investigation confirming the normalcy of the data residuals within the proc reg function.

Table 1.

P-Values from Multiple Linear Regression analysis.

| Dietary Effect | Treatment Effect | Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rel. Liver Weight | 0.5268 | <0.0001 -- ↑ | 0.8755 |

| Rel. Thymus Weight | 0.9956 | <0.0001 -- ↓ | 0.9574 |

| Hepatic CYP1A1 Expression | 0.9047 | <0.0001 -- ↑ | 0.8782 |

| Hepatic Lipids | 0.4750 | 0.0002 -- ↑ | 0.2105 |

| Hepatic ROS | 0.0002 -- ↑ | <0.0001 -- ↑ | 0.9574 |

| Hepatic CuZnSOD Activity | 0.0567 | 0.8792 | 0.0939 |

| Hepatic MnSOD Activity | 0.7847 | 0.0337 -- ↓ | 0.7352 |

| Hepatic Total SOD Activity | 0.1097 | 0.4760 | 0.1615 |

| Hepatic MTI Expression | <0.0001 -- ↑ | 0.0004 -- ↑ | 0.0144 |

| Hepatic MTII Expression | <0.0001 -- ↑ | 0.0019 -- ↑ | 0.0053 |

| Hepatic Cu | 0.9190 | <0.0001 -- ↑ | 0.6214 |

| Hepatic Zn | 0.0901 | 0.0123 -- ↓ | 0.3389 |

| Hepatic Se | 0.5948 | 0.0014 -- ↓ | 0.3549 |

| Hepatic Mn | 0.0109 -- ↓ | <0.0001 -- ↓ | 0.3551 |

| Renal Cu | 0.7722 | <0.0001 -- ↑ | 0.0003 |

| Renal Zn | <0.0001 -- ↑ | 0.0520 | 0.9045 |

| Renal Se | 0.0137 -- ↓ | 0.0002 -- ↑ | 0.9584 |

| Renal Mn | 0.0325 -- ↓ | 0.0146 -- ↑ | 0.6450 |

(Red indicates significance, p<0.05; arrow indicates positive or negative effect).

RESULTS

Growth and Feed Consumption

Severe zinc deficiency causes a wasting syndrome due to anorexia so the animals were monitored throughout the study for food intake. The level of zinc in the moderate zinc deficient diet caused decreased body weight gain, but no alterations in feed consumption (Figure S1). Zinc deficient animals were roughly 40% lighter than the adequate zinc and supplemental zinc animals at the end of the study. No difference was observed between the adequate and supplemented zinc groups. PCB126 is also known to cause wasting syndrome at higher doses that is manifested by hypophagia and general weight loss (cachexia). Within the exposure time period, there was no difference in the vehicle and PCB126 treated animals in any of the dietary groups.

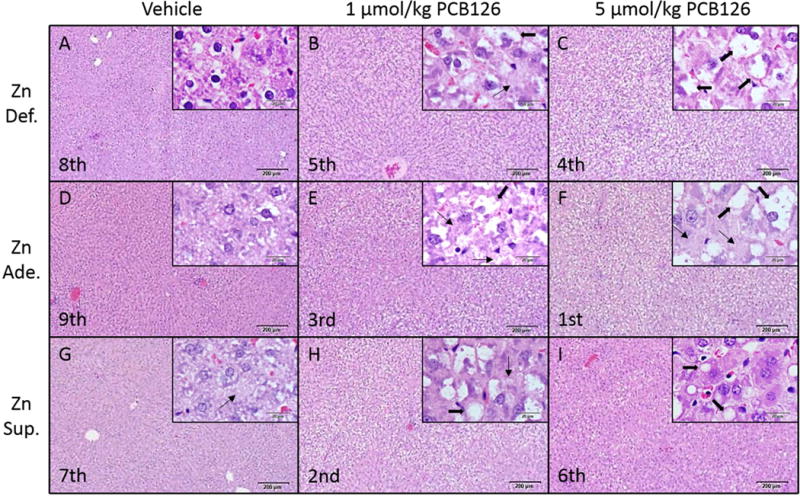

Histological Examination

The overall extent of PCB126 induced hepatotoxicity was determined by histological examination of H&E stained sections of the liver. Among the dietary groups, the vehicle-treated animals had slight alterations in hepatocellular pallor with mild diffused microvesicular vacuolation. Severe mixed (microvesicular and macrovesicular) hepatocellular vacuolation was observed with the treatment of PCB126 throughout the dietary groups (Figure 1). The most adversely effected group was the adequate zinc diet – high dose PCB group (Figure 1F). Interestingly, the zinc supplementation had a decrease in hepatocyte vacuolation in the high dose PCB126 reducing the extent of vacuolation seen below that of the low dose zinc supplementation group (Figure 1I). It appears that to some extent both the moderate zinc deficiency, to a smaller degree, and the supplementation of zinc imparted some protection against the effects of PCB126.

Figure 1. Histological examination of PCB126 hepatic effects and the mitigation by dietary zinc.

Sprague Dawley rats were fed one of three diets, ranging in zinc content from moderate zinc deficient (7 ppm), adequate zinc, (30 ppm), and supplemented zinc (300 ppm) for three weeks. Animals were treated with either a low dose (1 μmol/kg) or higher dose (5 μmol/kg) PCB126. De-identified liver sections were stained and examined. Pathological rankings of group severity, as measured by vacuolation, are listed in the lower left corner of the image (ex. Most severe – Zn Ade. High Dose) with a high magnification image in the upper right. Macro and microvesicular vacuolation are indicated by thick and thin arrows, respectively. These constitute representative images from each group. Large image scale bar – 200 μm. Inset image scale bar – 20 μm.

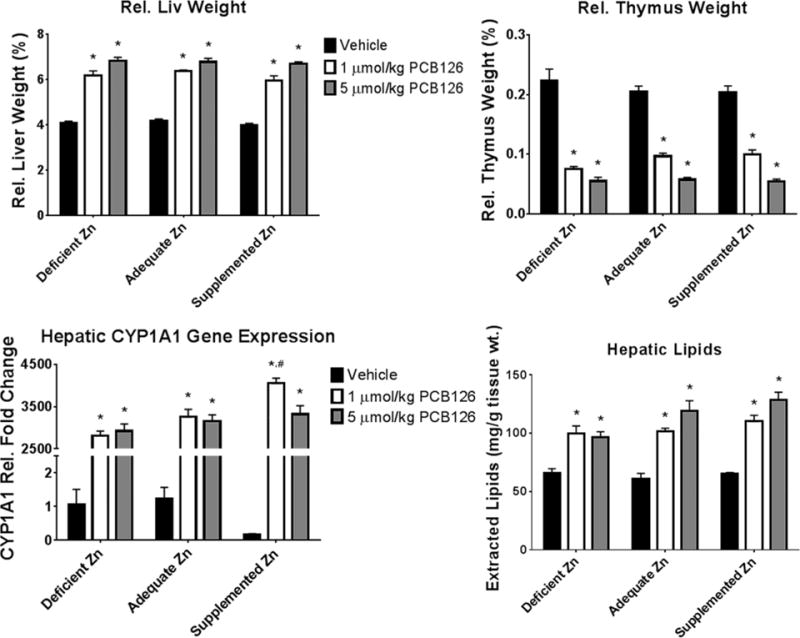

Hallmarks of AhR Activation

AhR activation was assessed to ensure canonically seen pathologies associated with PCB126 exposure and their alteration with dietary zinc. Relative liver weight was greatly increased with PCB126 exposure throughout the dietary groups (Figure 2). No difference was observed among the diets either within vehicle treated or the PCB126 groups. Relative thymic weight was drastically decreased with PCB126 exposure with no difference seen among the dietary zinc levels (Figure 2). Similar alterations were also observed in absolute liver and thymic weight however the zinc deficient animals had lighter organs overall (Figure S2). The induction of CYP1A1 is likely the most well-known outcome of PCB126 exposure and an efficacious induction was seen with exposure (Figure 2). Interestingly, the low dose PCB treated, supplemented zinc group had a more robust induction than the adequate and deficient zinc diets. This robust induction was not observed with the zinc supplemented, high dose PCB group whose induction was more moderate. The vehicle treated zinc supplemented animals had a decreased basal level of CYP1A1. Extractable hepatic lipids, a measure of lipid accumulation/vacuolation, increased with PCB126 exposure throughout the dietary groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Confirmation of traditional markers of AhR activation.

PCB126 is known to activate the AhR so canonical metrics were assessed including relative liver and thymus weight, CYP1A1 induction and lipid accumulation in the liver. (Bars are standard error; Two-Way ANOVA; n=6; * represents p<0.05 compared to vehicle in same diet; # represents p<0.05 compared to same treatment in adequate zinc diet).

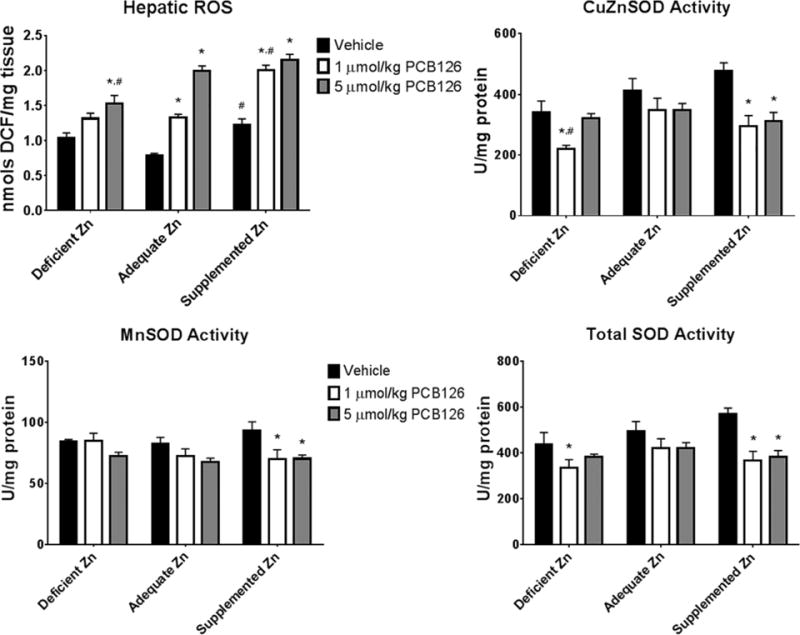

Oxidative Stress and Superoxide Dismutase Activity

ROS has long been associated with PCB126 exposure and was assessed here to investigate the role of dietary zinc in mitigating the oxidative stress. Hepatic ROS, as assayed by changes in DCFH2 oxidation, was increased with PCB126 exposure throughout the different diets (Figure 3). The basal dye oxidation levels in the supplemented diet vehicle treated animals was increased compared to the adequate zinc diet, similar to that seen with deficient zinc; however, the deficient zinc vehicle group failed to reach significance. The greatest ROS was seen in the supplemental zinc diet. Multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis showed that the zinc in the diet positively affected the extent of dye oxidation. Superoxide dismutase activity was evaluated for the antioxidant ability of the hepatic tissue. Through all the SOD activities investigated (CuZnSOD, MnSOD, and Total SOD), a decrease was seen with treatment of PCB126, this is most clearly seen with CuZnSOD and total SOD activity (Figure 3). It appears that CuZnSOD activity is altered somewhat by dietary zinc level; that is, lower activity with the deficient diet and higher activity with the supplemented diet. Significance was almost reached (p=0.0567) in the MLR analysis for a dietary effect but the multiple comparison failed to find significance except for the deficient zinc low dose PCB126 treatment group. The modulation of SOD activity also manifested in the total SOD as well.

Figure 3. Metrics of ROS induced by PCB126 and dietary zinc.

Total hepatic ROS along with superoxide dismutase activity was measured to evaluate the changes in ROS status caused by PCB126 and also dietary zinc. (Bars are standard error; Two-Way ANOVA; n=6; * represents p<0.05 compared to vehicle in same diet; # represents p<0.05 compared to same treatment in adequate zinc diet).

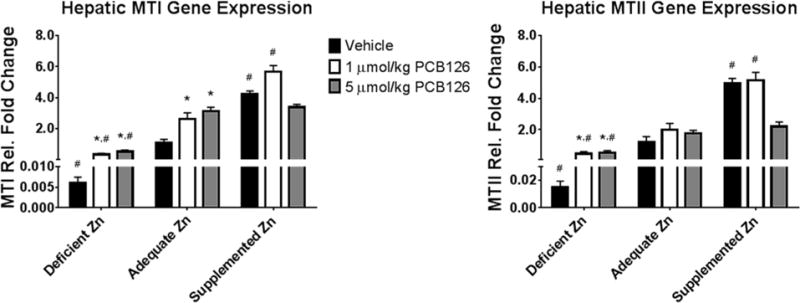

Metallothionein Gene Expression

Zinc supplementation is believed to lend its protective effects, in part, through induction of metallothionein so the expression of two ubiquitous isoforms of metallothionein were investigated. The diet had a great effect on the gene expression of metallothionein. Decreased levels were seen in the deficient zinc diet which PCB126 increased only to adequate diet-vehicle treated levels (Figure 4). In addition, zinc supplementation increased the levels of metallothionein to roughly 4-fold higher levels when compared with the adequate zinc diet. PCB126 increased metallothionein in the deficient and adequate zinc diets with no change in the supplemented zinc diet. The high dose PCB zinc supplemented group did not have as large of an induction compared to the low dose in the same diet and was actually decreased compared to vehicle. Both diet and PCB126 positively affected metallothionein expression in the MLR analysis with an interaction of both as well.

Figure 4. Induction of metallothionein by PCB126 and dietary zinc.

Metallothionein expression is altered by both factors in this study and was determined for its role in any mitigation. (Bars are standard error; Two-Way ANOVA; n=6; * represents p<0.05 compared to vehicle in same diet; # represents p<0.05 compared to same treatment in adequate zinc diet).

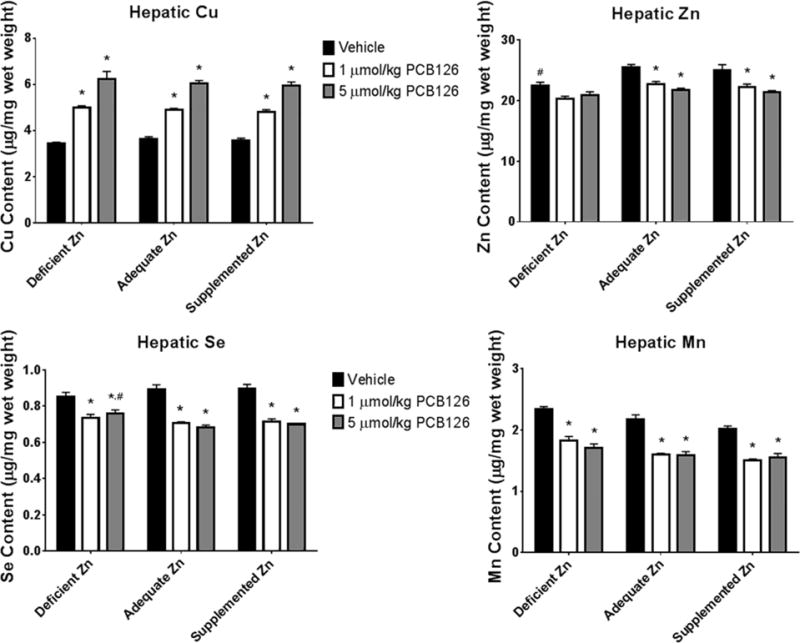

Micronutrient Analysis

The extent of micronutrient alteration caused by PCB126 and any attenuation by dietary zinc was probed using inductively-coupled plasma mass spectroscopy. Hepatic copper was increased in a dose dependent way with PCB126 exposure with no apparent effect by dietary zinc (Figure 5). Zinc deficiency caused a decrease in the level of hepatic zinc, but zinc supplementation did not increase it. Hepatic zinc was decreased following exposure to PCB126 among all diets with only the adequate and supplemented zinc being significant (both low and high dose) (Figure 5). Hepatic selenium was also seen to decrease with PCB126 exposure with no effect of dietary zinc. Hepatic manganese was effected by diet; decreasing while dietary zinc increased (significance seen in MLR analysis; Table 1). In addition, PCB126 caused a decrease in hepatic manganese levels which was not as severe in the zinc deficient group. In an effort to eliminate the possibility that the changes in hepatic metals concentrations were due to the lipid accumulation/hypertrophy seen, we expressed whole liver metals content over liver mass minus extracted fat. These data (Figure S3) demonstrate the same trends as those described above, indicating no effect of dilution due to lipid accumulation.

Figure 5. Changes in hepatic trace element status with PCB126 exposure and varying dietary zinc levels.

Micronutrient status was assessed for copper, zinc, selenium, and manganese in the liver which are known to alter with PCB126 exposure. (Bars are standard error; Two-Way ANOVA; n=6; * represents p<0.05 compared to vehicle in same diet; # represents p<0.05 compared to same treatment in adequate zinc diet).

The trace elements of the kidney were also examined (Figure S4). Little effect was seen in renal copper with only the zinc deficient high dose (5 μmol/kg) group being significant; although a treatment and interaction effect was seen with MLR analysis. The deficient zinc diet caused a decrease in renal zinc throughout the treatment groups. Similar to renal copper, renal selenium was only significant in the zinc deficient high dose group. Renal manganese had an inverse effect to that of renal zinc; zinc deficiency caused an increase in renal manganese similar to what was observed in the liver. In the MLR analysis, the diet negatively affected the levels of renal Se and Mn whereas the PCB126 treatment positively affected those elements.

DISCUSSION

This study set out to investigate the role of zinc in the hepatotoxicity associated with PCB126. Previous investigations have shown that PCB126 exposure causes decreases in hepatic zinc.27 In addition, zinc is important in the toxicity of other liver specific agents, like carbon tetrachloride and acetaminophen, since both deficiency and supplementation alter their toxicity. On the basis of these findings, the authors hypothesized that zinc deficiency would exacerbate PCB126 mediated liver injury and supplementation mitigate.

Both PCB126 and zinc deficiency are known to cause wasting like symptoms in animals either with high enough dose or severe enough deficiency.28, 29 Studies have indicated that TCDD, an AhR agonist similar to PCB126, causes alterations in micronutrient status that are independent of the decrease in feed consumption.30 Given the investigation of micronutrients involved, it is important to avoid doses that result in these pathologies, namely hypophagia/cachexia. Body weight and feed consumption were monitored over the course of the study to ensure that hypophagia and cachexia were not occurring. Although the zinc deficient diet resulted in lighter animals, feed consumption was not different among the groups (Figure S1). The lighter animals were likely the result of the zinc deficiency given that feed consumption was unchanged between dietary groups. In addition, no difference was observed in body weight within dietary groups following treatment with PCB126.

It is well established that PCB126 causes lipid accumulation in hepatocellular vacuoles; the degree of exacerbation/mitigation by dietary zinc was investigated here. Even within the vehicle treated animals, mild vacuolation was seen within the liver (Figure 1). Previous investigations have seen subtle alterations in liver histology with a similar level of zinc deficiency and zinc supplementation in mice.15, 31 Pathological examination determined that the extent of hepatocyte vacuolation was greatest with the control diet with little rescue by both the zinc deficiency and supplementation. A particularly noted rescue was observed in the high dose PCB, zinc supplemented group. However no additional metrics of PCB toxicity (relative liver and thymic weight, liver lipids, and ROS) were reversed with the high dose supplemented data. Interestingly, the gene expression data (CYP1A1, MTI, and MTII) show a reduction in expression in the high dose supplemented group compared with the low dose counterpart, similar to what is seen histologically. This may suggest that the more overt indications of toxicity are not sensitive enough to see the subtle alterations that are happening within that subgroup.

Clear signs of AhR activation are known to include increases in liver weight, thymic involution, cytochrome P450 induction, and hepatic lipid accumulation.4 All of these metrics were investigated in this study and were indicative of a positive AhR activation however little difference was seen between the different diets. Relative liver weight was dose dependently increased with PCB126 exposure (Figure 2). As has been previously shown, this is likely hepatocellular hypertrophy which can also be seen in the histology with hydropic change and lipid vacuolation.32 Although zinc deficiency has been shown to depress the immune system, the effect was not displayed in the relative thymic weight that was dose dependently decreased with PCB126 treatment.33 In addition, absolute liver and thymic weights had similar alterations however the zinc deficient animals had lighter organs overall consistent with the lighter body weight seen (Figure S2). A robust induction of the family 1 cytochrome P450 metabolizing enzymes was seen with PCB126 (Figure 2). Changes in zinc status, in particular deficiency, has been shown to decrease the expression of cytochrome P450s, however increases were observed here in the vehicle treated supplemented zinc group.9, 34 Given the lack of zinc in the AhR and few studies investigating this association, further studies are warranted to better understand zinc mediated AhR signaling. Hepatic lipids also increased with PCB126 with little effect of dietary zinc (Figure 2). Interestingly, hepatic lipids should be a relevant marker of the degree of lipid accumulation/hepatocyte vacuolation caused by PCB126 however the mass of hepatic lipids measured was not always consistent with the degree of vacuolation seen in the histology. In particular, the zinc supplemented – high dose PCB126 group showed an improved histology which was not seen in the hepatic lipids. Given the unexpected change in gene expression of CYP1A1 (Figure 2) and the MTs (Figure 4) in the zinc supplemented – high dose PCB126 group, the histological change that is seen is unlikely due to error and is likely a unique result of increased zinc and high PCB126 exposure. Further studies are warranted to investigate these effects in more detail.

Hepatic ROS as assayed by dye oxidation was increased with exposure to PCB126 and the zinc supplemented group showed higher levels of ROS than the adequate and deficient zinc diets (Figure 3). This is contrary to what was originally hypothesized; that zinc deficiency would have higher levels. The level of zinc supplementation that was used in this study has been widely used with no ill effects.13, 35 Although the zinc supplemented groups had marginally higher ROS, the PCB-induced histologic changes were less severe as were other adverse endpoints investigated, outside the gene expression data, were no different from the other diets. This suggests that the availability of dietary zinc allows for a better capacity to handle the oxidative stress or that the elevated ROS may not be an adverse effect. Additional research into the relationship between supplemented zinc and ROS may be warranted. Superoxide dismutase activity was decreased with PCB126 exposure, consistent with what had been found previously (Figure 3).7 Contention exists whether dietary zinc can alter the levels/activity of Cu/ZnSOD. Some studies found changes and others not.36–38 Here, according to the MLR analysis, dietary zinc did alter the activity of Cu/ZnSOD (p=0.0567; Table 1) with lower activity at low levels and high activity at high levels. Any increases in SOD activity were dampened by treatment with PCB126, lowering SOD activity to levels observed with adequate diet. Surprisingly, the hepatic ROS did not mimic the decrease in activity of SOD at least in the vehicle animals. The lack of correspondence may be the result of the presence of other important antioxidant proteins, given that the oxidation sensitive dye used to determine ROS does not discriminate among the oxidants that will convert it to a florescent compound. Previous studies have demonstrated an increase in other antioxidant enzymes after exposure to PCB126, in particular metallothionein, glutathione transferase, and total glutathione peroxidase.6, 27

Alterations in metallothionein expression by dietary zinc have been observed before and are believed, in part, to exert its beneficial effects. Clear changes in metallothionein expression are observed with dietary zinc in this study with large differences in expression seen between zinc deficiency and zinc supplementation (Figure 4). Even induction of MT by PCB126 brought the level of metallothionein only to control levels in the zinc deficient diet.39 Whereas with zinc supplementation basal metallothionein levels are 4 fold higher than adequate diet levels. This would suggest that any amelioration that was observed in the zinc deficient diet (lower ROS, decreased liver lipids, and histological ranking) is likely independent of metallothionein whereas the same cannot be said for the zinc supplemented group given the significant induction seen.

Micronutrient disruptions in the liver are well known with PCB126 and this study has found similar changes to those previously reported.4, 27, 40 Hepatic copper was increased in a dose dependent fashion, whereas zinc, selenium, and manganese were decreased (Figure 5). The zinc deficient diet did cause lower hepatic zinc levels whereas zinc supplementation did not increase levels. The modulation of hepatic zinc (deficiency causing lower levels and supplementation maintaining control levels) as a result of dietary zinc has been found before in previous dietary zinc studies.31, 38 In addition, the elevation of zinc in the kidneys (Table 1) in the zinc supplemented group suggests that zinc supplementation does have an effect on overall zinc levels. Interestingly, the only metal to have a dietary effect outside of zinc was manganese; which was seen to decrease with increasing zinc. Fujimura et. al. demonstrated decreases in hepatic manganese with higher dietary zinc levels and hypothesized a connection to the downregulation of Zip8, a manganese transporter.41

The hepatoprotective effects of zinc supplementation are well known and have mitigated the toxicity for several hepatotoxicants.8–11 This investigation set out to determine if dietary zinc can alter the hepatotoxicity associated with PCB126, a potent and persistent environmental pollutant. Histological examination suggested some amelioration by both zinc deficiency and supplementation although only mildly. However, other overt measures of toxicity, (relative liver and thymus weight, liver lipids, ROS) were not offset by dietary zinc and bring into question the mitigative role of dietary zinc with this agent. Carbon tetrachloride, ethanol, acetaminophen and viral hepatitis have all shown hepatic improvements with zinc supplementation; here that was not the case. This study exemplifies the unique and potent hepatic effects seen with acute PCB126 exposure. In addition, the contribution of decreased zinc in PCB126 toxicity seems minor given the rather insignificant changes found here. Previous studies suggest that other micronutrients may be better suited as a preventive strategy to mitigate the adverse effects of PCB126.6, 7, 42

Acknowledgments

All opinions given are those of the authors and not of any granting agency. The authors thank Dr. Gregor Luthe for the synthesis of PCB126, Dr. Hans Lehmler for maintenance of the stock, and Dr. Kai Wang for help with the statistics. In addition, the authors thank all lab members and especially Ms. Susanne Flor for their assistance with the infrastructure of the laboratory and the animal study.

FUNDING INFORMATION:

This research forms a portion of the dissertation work of W. Klaren and was supported by NIH funding (P42 ES013661). Drs. Spitz and McCormick were supported by NIH RO1 CA182804 and P30 CA086862, support for the Radiation and Free Radical Research Core. W. Klaren graciously acknowledges the support from the Iowa Superfund Research Program (P42 ES013661) Training Core.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PCB126

3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl

- PCB

Polychlorinated Biphenyls

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- RNS

Reactive Nitrogen Species

- CuZnSOD

Cu/Zn Superoxide dismutase

- MnSOD

Mn Superoxide dismutase

- CYP

Cytochrome P450 Enzymes

- AhR

Aryl-hydrocarbon Receptor

- IP

Intraperitoneal

- H&E

Hematoxylin and Eosin

- RT-PCR

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

- PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- cDNA

Complimentary DNA

- IDT

Integrated DNA Technologies

- DCFH2

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein

- DCF

2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein

- ICP-MS

Inductively Coupled Plasma – Mass Spectrometry

- MLR

Multiple Linear Regression

- CYP1A1

Cytochrome P450 family 1

- subfamily A

member 1

- MT

Metallothionein

- MTI

Metallothionein Isoform 1

- MTII

Metallothionein Isoform 2

- SOD

Superoxide Dismutase

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin

- Zip8

Zinc Transporter ZIP8 (solute carrier family 39 member 8)

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION:

Table S1: Primer sequences used for gene expression analysis.

Table S2: P-Values from Two-Way ANOVA Analysis.

Figure S1: Growth and Feed Consumption throughout the study.

Figure S2: Absolute organ weights for liver and thymus.

Figure S3: Hepatic metal (Cu, Zn, Se, Mn) changes with the omission of hepatic lipids.

Figure S4: Renal metal (Cu, Zn, Se, Mn) changes.

This material is free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Ampleman MD, Martinez A, DeWall J, Rawn DF, Hornbuckle KC, Thorne PS. Inhalation and dietary exposure to PCBs in urban and rural cohorts via congener-specific measurements. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:1156–1164. doi: 10.1021/es5048039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu D, Lehmler HJ, Martinez A, Wang K, Hornbuckle KC. Atmospheric PCB congeners across Chicago. Atmos Environ. 2010;44:1550–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lauby-Secretan B, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Ghissassi FE, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Baan R, Mattock H, Straif K, International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group Iarc, L. F Carcinogenicity of polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated biphenyls. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:287–288. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai I, Chai Y, Simmons D, Luthe G, Coleman MC, Spitz D, Haschek WM, Ludewig G, Robertson LW. Acute toxicity of 3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 126) in male Sprague-Dawley rats: effects on hepatic oxidative stress, glutathione and metals status. Environ Int. 2010;36:918–923. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abel J, Haarmann-Stemmann T. An introduction to the molecular basics of aryl hydrocarbon receptor biology. Biol Chem. 2010;391:1235–1248. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai IK, Chai Y, Simmons D, Watson WH, Tan R, Haschek WM, Wang K, Wang B, Ludewig G, Robertson LW. Dietary Selenium as a Modulator of PCB 126-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Male Sprague-Dawley Rats. Toxicol Sci. 2011;124:202–214. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang B, Klaren WD, Wels B, Simmons DL, Olivier A, Wang K, Robertson LW, Ludewig G. Dietary manganese modulates PCB126 toxicity, metal status, and MnSOD in the rat. Toxicol Sci. 2015;150:15–26. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang X, Zhong W, Liu J, Song Z, McClain CJ, Kang YJ, Zhou Z. Zinc supplementation reverses alcohol-induced steatosis in mice through reactivating hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. Hepatology. 2009;50:1241–1250. doi: 10.1002/hep.23090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabre M, Camps J, Ferre N, Paternain JL, Joven J. The Antioxidant and Hepato-Protective Effects of Zinc are Related to Hepatic Cytochrome P450 Depression and Metallothionein Induction in Rats with Expreimental Cirrhosis. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2001;71:229–236. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.71.4.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishida T, Ohata S, Kusumoto C, Mochida S, Nakada J, Inaqaki Y, Ohta Y, Matsura T. Zinc supplementation with Polaprezinc Protects Mouse Hepatocytes against Acetominophen-Induced Toxicity via Induction of Heat Shock Protein 70. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2010;46:43–51. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.09-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumura H, Nirei K, Nakamura H, Arakawa Y, Higuchi T, Hayashi J, Yamagami H, Matsuoka T, Ogawa M, Nakajima N, Tanaka N, Moriyama M. Zinc supplementation therapy improves the outcome of patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2012;51:178–184. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.12-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis SR, Samuelson DA, Cousins RJ. Metallothionein Expression Protects against Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Hepatotoxicity, but Overexpression and Dietary Zinc Supplementation Provide No Further Protection in Metallothionein Transgenic and Knockout Mice. J Nutr. 2001;131:215–222. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Z. Zinc and alcoholic liver disease. Dig Dis. 2010;28:745–750. doi: 10.1159/000324282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC., and NCHS. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Questionaire (or Examination Protocol, or Laboratory Protocol) Hyattsville (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001–2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong W, Zhao Y, Sun X, Song Z, McClain CJ, Zhou Z. Dietary zinc deficiency exaggerates ethanol-induced liver injury in mice: involvement of intrahepatic and extrahepatic factors. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kojima-Yuasa A, Kamatani K, Tabuchi M, Akahoshi Y, Kennedy DO, Matsui-Yuasa I. Zinc deficiency enhances sensitivity to carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2011;25:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Himoto T, Nomura T, Tani J, Miyoshi H, Morishita A, Yoneyama H, Haba R, Masugata H, Masaki T. Exacerbation of insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis deriving from zinc deficiency in patients with HCV-related chronic liver disease. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2015;163:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-0177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luthe GM, Schut BG, Aaseng JE. Monofluorinated analogues of polychlorinated biphenyls (F-PCBs): Synthesis using the Suzuki-coupling, characterization, specific properties and intended use. Chemosphere. 2006;77:1242–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waalkes MP, Kovatch R, Rehm S. Effect of Chronic Dietary Zinc Deficiency on Cadmium Toxicity and Carcinogenesis in the Male Wistar Rat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1991;108:448–456. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(91)90091-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waalkes MP. Effect of dietary zinc deficiency on the accumulation of cadmium and metallothionein in selected tissues of the rat. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1986;18:301–313. doi: 10.1080/15287398609530870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC., Jr AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123:1939–1951. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bunaciu RP, Tharappel JC, Lehmler HJ, Kania-Korwel I, Robertson LW, Srinivasan C, Spear BT, Glauert HP. The effect of dietary glycine on the hepatic tumor promoting activity of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in rats. Toxicology. 2007;239:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.06.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spitz DR, Oberley LW. An assay for superoxide dismutase activity in mammalian tissue homogenates. Anal Biochem. 1989;179:8–18. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitz DR, Oberley LW. Measurement of MnSOD and CuZnSOD activity in mammalian tissue homogenates. Curr Protoc Toxicol Suppl. 2001;85(7):5, 1–7, 11. doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx0705s08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spitz DR, Elwell JH, Sun Y, Oberley LW, Oberley TD, Sullivan SJ, Roberts RJ. Oxygen toxicity in control and H2O2-resistant Chinese hamster fibroblast cell lines. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;279:249–260. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90489-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klaren WD, Gadupudi GS, Wels B, Simmons DL, Olivier AK, Robertson LW. Progression of micronutrient alteration and hepatotoxicity following acute PCB126 exposure. Toxicology. 2015;338:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gadupudi GS, Klaren WD, Olivier AK, Klingelhutz AJ, Robertson LW. PCB126-induced disruption in gluconeogenesis and fatty acid oxidation precedes fatty liver in male rats. Toxicol Sci. 2016;149:98–110. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caulfield LE, Richard SA, Rivera JA, Musgrove P, Black RE. Stunting, Wasting, and Micronutrient Deficiency Disorders. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. Wolrd Bank; Washington (DC): 2006. pp. 551–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elsenhans B, Forth W, Richter E. Increased copper concentrations in rat tissues after acute intoxication with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Arch Toxicol. 1991;65:429–432. doi: 10.1007/BF02284268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou Z, Wang L, Song Z, Saari JT, McClain CJ, Kang YJ. Zinc Supplementation Prevents Alcoholic Liver Injury in Mice through Attenuation of Oxidative Stress. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1681–1690. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62478-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ovando BJ, Ellison CA, Vezina CM, Olson JR. Toxicogenomic analysis of exposure to TCDD, PCB126 and PCB153: identification of genomic biomarkers of exposure to AhR ligands. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:583. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dardenne M, Boukaiba N, Gagnerault MC, Homo-Delarche F, Chappuis P, Lemonnier D, Savino W. Restoration of the thymus in aging mice by in vivo supplementation. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;66:127–135. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen H, Arzuaga X, Toborek M, Henning B. Zinc Nutritional Status Modulates expression of AhR-Responsive P450 Enzymes in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2008;25:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammad MK, Zhou Z, Cave M, Barve A, McClain CJ. Zinc and liver disease. Nutr Clin Prac. 2012;27:8–20. doi: 10.1177/0884533611433534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun JY, Jing MY, Weng XY, Fu LJ, Xu ZR, Zi NT, Wang JF. Effects of Dietary Zinc Levels on the Activities of Enzymes, Weights of Organs, and the Concentrations of Zinc and Copper in Growing Rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2005;107:153–165. doi: 10.1385/BTER:107:2:153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho E, Courtemanche C, Ames BN. Zinc Deficiency Induces Oxidative DNA Damage and Increases P53 Expression in Human Lung Fibroblasts. J Nutr. 2003;133:2543–2548. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.8.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jing MY, Sun JY, Zi NT, Sun W, Qian LC, Weng XY. Effects of Zinc on Hepatic Antioxidant systems and the mRNA Expression Levels Assayed by cDNA Microarrays in Rats. Ann Nutr Metab. 2009;51:345–351. doi: 10.1159/000107677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato S, Shirakawa H, Tomita S, Tohkin M, Gonzalez FJ, Komai M. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor and glucocorticoid receptor interact to activate human metallothionein 2A. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;273:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai I, Klaren WD, Li M, Wels B, Simmons D, Olivier AK, Haschek WM, Wang K, Ludewig G, Robertson LW. Does Dietary Copper Supplementation Enhance or Diminish PCB126 Toxicity in the Rodent Liver? Chem Res Toxicol. 2013;26:634–644. doi: 10.1021/tx400049s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujimura T, Terachi T, Funaba M, Matsui T. Reduction of liver manganese concentration in response to the ingestion of excess zinc: identification using metallomic analyses. Metallomics. 2012;4:847–850. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20100c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai I, Dhakal K, Gapdupudi G, Miao L, Ludewig G, Robertson LW, Olivier A. N-acetylcystiene (NAC) diminishes the severity of PCB126-induced fatty liver in male rodents. Toxicology. 2012;302:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]