Abstract

Objective:

The Dahl salt-sensitive rat is a well-established model of salt-sensitive hypertension. The goal of this study was to assess the expression and activity of renal sodium channels and transporters in the renin-deficient salt-sensitive rat.

Methods:

Renin knockout (Ren−/−) rats created on the salt-sensitive rat background were used to investigate the role of renin in the regulation of ion transport in salt-sensitive hypertension. Western blotting and patch-clamp analyses were utilized to assess the expression level and activity of Na+ transporters.

Results:

It has been described previously that Ren−/− rats exhibit severe kidney underdevelopment, polyuria, and lower body weight and blood pressure compared to their wild-type littermates. Here we found that renin deficiency led to decreased expression of sodium-hydrogen antiporter (NHE3), the Na+/H+ exchanger involved in Na+ absorption in the proximal tubules, but did not affect the expression of Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC2), the main transporter in the loop of Henle. In the distal nephron, the expression of sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC) was lower in Ren−/− rats. Single-channel patch clamp analysis detected decreased ENaC activity in Ren−/− rats which was mediated via changes in the channel open probability.

Conclusion:

These data illustrate that renin deficiency leads to significant dysregulation of ion transporters.

Keywords: Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, sodium-hydrogen antiporter, sodium chloride cotransporter, Na-K-Cl cotransporter, epithelial sodium channel, aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron

Introduction

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is the central regulator of water and salt homeostasis in the body. Components of this hormonal cascade are major targets for pharmaceutical agents aimed at controlling blood pressure, and heart and kidney functions. Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) SS/JrHsdMcwi rats are extensively used to study the role of salt consumption in the development of hypertension. These rats, when kept on a high salt diet, exhibit remarkable phenotypic traits similar to those seen in the hypertensive African American population, including low renin, salt-sensitivity, hyperinsulinemia, and early end stage renal disease.1–3

Previous studies have shown that introgression of chromosome 13 (Chr 13) from the Brown Norway (BN) rat into the SS genetic background attenuates the development of hypertension in an SS-13BN consomic strain. While Chr 13 contains the renin gene, further studies, which narrowed the protective loci in the SS-13BN rats against salt-sensitivity, did not identify the renin gene in these regions.4–6 However, a number of other studies demonstrated that genetic modification of the renin locus does affect blood pressure.7–10 Previously, we generated a renin knockout (Ren−/−) in the SS rat using zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) designed to target the renin gene.11 These rats have undetectable plasma renin activity, underdeveloped kidneys as well as significantly lower mean arterial pressure than their Ren+/+ littermates. There was also evidence of decreased renal function, reflected by polyuria, reduced creatinine excretion and creatinine clearance in Ren−/− rats.11

Regulation of sodium balance by the kidney is the key factor responsible for long-term blood pressure control. Dahl SS rats demonstrate an impaired sodium excretion response to increases in renal perfusion pressure. This predisposes them to developing hypertension when challenged with a high salt diet.12 In the present study we describe the effects of renin deficiency on several key sodium transporters in various nephron segments.

Materials and methods

Animals

ZFN-mediated renin gene knockout (Ren−/−) rats and their wild-type (Ren+/+) littermates were created11 and housed at the Medical College of Wisconsin, and all work was conducted under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male rats were fed 0.4% NaCl diet (#113755, Dyets, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA). At the age of eight weeks, the rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, blood samples were collected from the descending aorta, and the kidneys were flushed with phosphate buffer and used for further analysis.13

Plasma aldosterone and corticosterone levels

Collected blood samples were centrifuged (6000 g, 10 min), and then plasma was analyzed with the Aldosterone and Corticosterone Active RIA kits (MP Biomedicals, Orangeburg, New York, USA).

Patch-clamp analysis

Patch-clamp electrophysiology was used to assess ENaC activity in isolated, split-open rat connecting tubule/cortical collecting duct (CNT/CCD) segment. CNT/CCDs were isolated from Ren−/− and Ren+/+ rats as described previously.14,15 Kidneys were cut into thin slices (<1 mm) and then placed into ice-cold physiologic saline solution (pH 7.4). CNT/CCD regions were mechanically isolated from these slices under a stereomicroscope by micro-dissection with forceps. The tubules were split open with sharpened micropipettes controlled with micromanipulators to gain access to the apical membrane. Single-channel recordings were acquired with Axopatch 200B or 700B amplifiers (Mol. Devices, Sunnyvale, California, USA) interfaced via a Digidata 1440A to a personal computers (PC) running the pClamp 10.2 suite software (Mol. Devices) and subsequently analyzed with Clampex 10.2. Currents were filtered with an eight-pole, low pass Bessel filter LPF-8 (Warner Inst., Hamden, Connecticut, USA) at 0.3 kHz. A typical bath solution was used (in mM): 150 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). The pipette solution for the cell attached configuration was (in mM): 140 LiCl, 2 MgCl2 and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). NPo, the product of the number of channels and the open probability (Po) were used to measure the channel activity within a patch. When multiple channel events were observed in a patch, the total number of functional channels (N) in the patch was determined.

Western blot analysis

Kidney total lysate was prepared as described previously.15 Briefly, kidneys were cut in 1–2 mm slices under a stereomicroscope. Kidney cross-sections (~50 mg) were diced into small pieces with a razor blade. Samples were pulse sonicated in Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad #161-0737) with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) for 10 s and spin cleared at 10,000 g for 5 min. The resulting supernatant was subjected to PAGE, subsequently transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA), probed with antibodies, and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Fisher Sci #32106). The visualization and densitometric analysis was done on the ChemiDoc XRS+ System with Image Lab Software containing a band saturation control. Densities were normalized to the corresponding β-actin intensities and then relative values were averaged in groups. Primary antibodies for sodium-hydrogen antiporter (NHE3), α-, β- and γ-ENaC (SPC-400D, SPC-403D, SPC-404D and SPC-405D, respectively) were from StressMarq Biosciences Inc. (Victoria, British Columbia, Canada);16 antibodies for sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC) were kindly provided by David H Ellison (Oregon Health & Science University, Portland),17,18 and Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC2) by Pablo Ortiz (Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit).19,20

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis

Extracted kidneys were placed into a neutral buffered 10% formalin solution. The kidney sections were cut at 4 μm slices, dried, and deparaffinized for subsequent streptavidin-biotin immunohistochemistry. After deparaffinization, the slides were treated with a citrate buffer pH6 for a total of 35 min. The slides were blocked with a peroxidase block (DAKO, Carpinteria, California, USA), Avidin Block (Vector Labs, Burlingame, California, USA), Biotin Block (Vector Labs), and serum-free Protein Block (DAKO). For morphological analysis, the tissue was stained with hematoxylin-eosin. For immunohistochemical staining, tissue sections were incubated for 30 min with anti-α, β or γ-ENaC antibodies. Secondary detection was performed with goat anti-rabbit biotinylated immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Biocare, Concord, California, USA) followed by streptavidin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Biocare) and visualized with diaminobenzadine (DAKO).

Statistical analysis

All summarized data are reported as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). Data are compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey correction and p<0.05 is considered significant.

Results

Kidney morphology, plasma aldosterone, corticosterone, and electrolyte levels

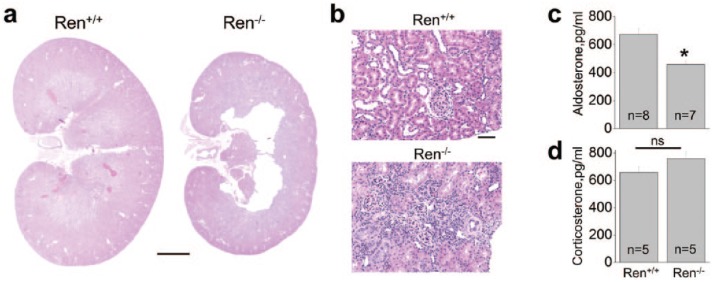

Ren−/− rats were previously reported to differ from their Ren+/+ littermates by having significantly lower body weights and kidney underdevelopment marked by displaced medulla, incomplete formation of the medullary rays, and occurrence of large central lesions.11 Figures 1(a) and (b) confirm the presence of structural abnormalities in Ren−/− kidneys, significant thinning of the medullar layer, and massive areas of undifferentiated tissue in the cortex. The low-renin plasma activity and angiotensin I levels reported earlier11 are in accordance with our evaluation of the plasma aldosterone concentration, which was found to be significantly lower in Ren−/− rats (Figure 1(c)). Plasma corticosterone level did not differ significantly between the groups (Figure 1(d)).

Figure 1.

Kidney morphology and plasma aldosterone levels of wild-type (Ren+/+) and renin knockout (Ren−/−) rats. (a) Magnified view of renal midline section from Ren+/+ and Ren−/− rats. Significant thinning of medullar layer and loss of tissue in central part of the Ren−/− rat kidney are clearly visible. Scale bar is 4 mm. (b) Hematoxylin-eosin staining of cortical layer shows the presence of large areas of undifferentiated tissue. Scale bar is 50 μm. (c) Plasma aldosterone and (d) corticosterone concentrations in Ren−/− rats and their Ren+/+ littermates. Number of rats used for analysis is shown. *p<0.05 versus Ren+/+ rats.

Western blot analysis of renal sodium transporters

Absolute sodium excretion and plasma Na+ concentration in Ren−/− rats did not differ from their Ren+/+ littermates.11 However, the mutant animals demonstrated substantial polyuria (especially when considering their low weight).

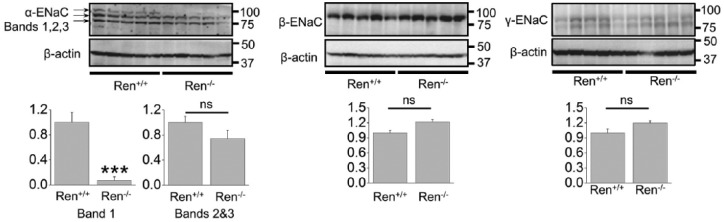

Several Na+ transporters expressed in the nephron mediate sodium absorption in the kidney: NHE3 and sodium-glucose transport protein (SGLT) in the proximal tubules, NKCC2 in the loop of Henle, NCC in the distal convoluted tubules and epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron, including late part of DCT, CNT and CCD.21 Figure 2 demonstrates Western blot analysis of several of these transporters in the Ren−/− rats and their wild type littermates. NHE3 expression was lower in the Ren−/− group (Figure 2(a)) whereas the expression of NKCC2 was not altered (Figure 2(b)). We tested the consequences of renin deficiency on abundance of the thiazide-sensitive NaCl co-transporter, NCC, and found significantly lower expression of NCC in the mutant animals (Figure 2(c)).

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of sodium transporters (sodium-hydrogen antiporter (NHE3), Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC2) and sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC)) in the kidney total lysates from wild type and Ren−/− rats. Summary graphs represent the average relative density of the bands (normalized to β-actin) in the groups. *p<0.05 versus Ren+/+ rats.

ENaC abundance and activity measurements

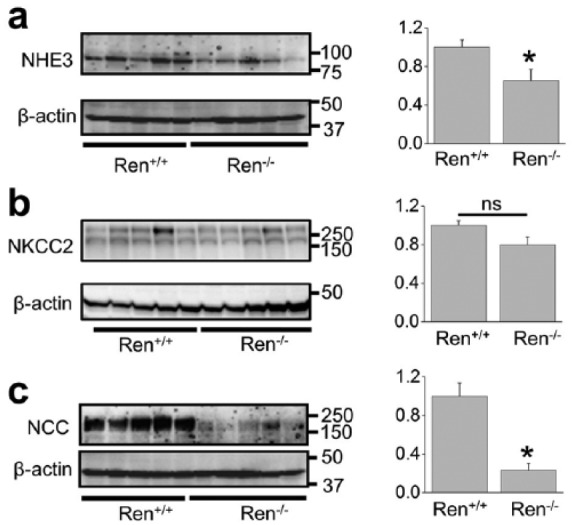

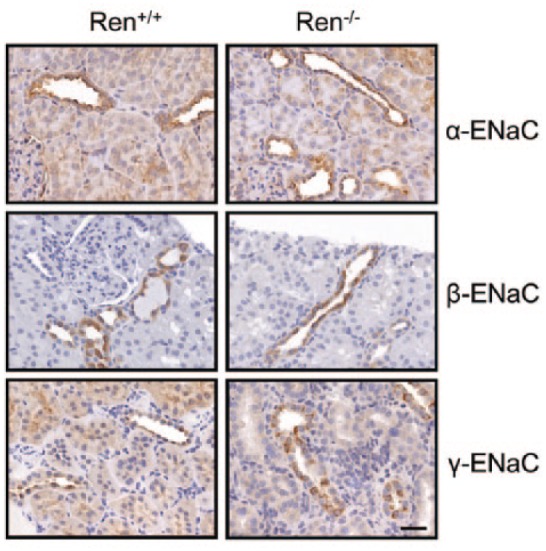

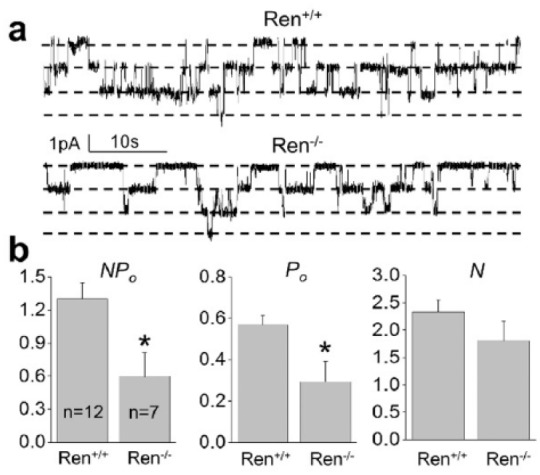

Normally, cortical ENaC performs only ~5% of sodium reabsorption. However, this widely regulated channel is involved in the fine tuning of sodium transport in the kidney and is a key element in the antinatriuretic response to aldosterone.16,22 Surprisingly, Western blot (Figure 3) and immunohistochemical (Figure 4) analyses revealed that the expression of all three ENaC subunits did not differ between the groups. The only difference we noted was that expression of a ~90 kDa band of α-ENaC was significantly lower in Ren−/− animals (band 1; Figure 3). It should be noted, however, that we did not analyze the cleaved forms of α- and γ-ENaC subunits, which play critical roles in the activity of the channel.23 To further test whether renin deficiency affects functions of ENaC, we performed single channel analysis using the cell-attached configuration of the patch-clamp method. Figure 5(a) demonstrates representative current traces recorded from the apical membranes of CCDs isolated from Ren+/+ and Ren−/− rats. We found that mutant rats exhibited significantly lower total ENaC activity (NPo) compared to Ren+/+ littermates. The average number of channels observed in each experiment (N) did not significantly vary between groups, but the lower NPo in the Ren−/− animals was caused by changes in the open probability of individual channels (Po) (Figure 5(b)). Therefore, these data allow us to conclude that absence of renin decreases the activity of ENaC by alteration of gating properties but not expression of the channel.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of α-, β-, and γ- epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) subunits in renin knockout (Ren−/−) and wild type (Ren+/+) littermates. ***p<0.001 versus Ren+/+ rats.

Figure 4.

Expression of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) in renin knockout (Ren−/−) and wild type (Ren+/+) rats. Immunohistochemical staining for α-, β-, and γ-ENaC subunits in the kidney cortical sections of Ren+/+ and Ren−/− rats. 40× magnification, scale bar is 50 μM.

Figure 5.

Patch clamp analysis of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) in renin knockout (Ren−/−) and wild type (Ren+/+) rats. (a) Representative current traces from cell-attached patches containing ENaC and recorded from the apical membrane of split-opened connecting tubule/cortical collecting duct (CNT/CCD) tubules of wild type and Ren−/− rats. Holding potential is −60 mV. (b) Summary graphs of ENaC activity (NPo), number of channels (N) and channel open probability (Po) in cell-attached patches. *p<0.05 versus Ren+/+ rats.

Discussion

The role of the RAAS components in the management of sodium reabsorption and excretion is still not fully understood. SS rats are a low renin strain, and high salt consumption decreases plasma renin activity even further,24–26 yet SS hypertension is accompanied with activation of the paracrine RAAS system.24,26,27 Furthermore, adrenalectomized SS rats do not develop hypertension on a high salt diet, whereas exogenous aldosterone supplement reverses this phenomenon.28 Renin knockout failed to concentrate urine and have lower plasma angiotensin I11 and aldosterone levels. Angiotensin II and aldosterone were described as positive regulators of several channels and transporters in the kidney, including ENaC.29–31

Our goal was to investigate functions of major sodium transport proteins along the nephron in the condition of renin deficiency and the lack of aldosterone in the system. We found that NKCC2 abundance did not change in mutant compared to wild type animals whereas the other tested sodium transporters exhibited reduced functions. Thus, NHE3 abundance as well as NCC expression was lower in the mutant animals. RAAS is a potent regulator of sodium reabsorption in the distal segments of the nephron. Aldosterone stimulates thiazide-sensitive sodium reabsorption, an effect accompanied with an increase in NCC abundance.32–34 It was previously reported that salt restriction leads to increased plasma renin activity, aldosterone levels, and NCC abundance.35 Angiotensin II positive regulation of NCC functions was also described.36–39 As mentioned above, RAAS is a powerful regulator of ENaC activity. We did not find significant differences in ENaC abundance between the groups, but Western blotting revealed diminished presence of a ~90 kDa form α-ENaC subunit in the Ren−/− rats. Previously Ergonul and colleagues demonstrated that maturation of ENaC was accompanied with glycosylation of the α-subunit, which might play a role in current conditions.40 We further utilized the patch-clamp approach to perform a functional assay and found that ENaC activity in the Ren−/− isolated CCDs was lower due to decreased open probability of the channel.

Recent studies also identified that kidney-specific mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) knockout mice exhibited salt wasting, low BP, and hyperkalemia.18 It was reported that knockout of MR in the kidney resulted in deficient apical orientation and cleavage of ENaC. NCC and pNCC abundances were also substantially reduced in the kidney-specific MR−/− mice. Plasma K+ was elevated in the MR−/− mice. The authors concluded that the effects on NCC were secondary to the changes in plasma K+ since dietary K+ restriction of kidney-specific MR−/− mice maintained the abundance of pNCC at a level similar to or greater than control.18 This mechanism may be important in the Ren−/− rats since it was previously shown that serum potassium was significantly increased in Ren−/− rats.41 The authors also demonstrated in vitro that the corticosterone basal levels and production by zona reticularis/fasciculata cells in response to cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) was unaffected in the Ren−/− rat compared with the Ren+/+ controls. Our in vivo experiments accordingly revealed equal plasma levels of corticosterone in Ren−/− and Ren+/+ littermates. We assume that the Ren−/− strain of Dahl SS rats can be considered a model of isolated hypoaldosteronism but further studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

The Ren−/− rat strain is a very exciting model which delineates the role of local intrarenal processes when systemic RAAS activity is low. For instance, recent studies using this model defined basal and cAMP-stimulated aldosterone production in the zona glomerulosa cells.41 Further characterization of sodium balance in these animals is required as we hypothesize that low systemic RAAS activity is the cause of very low blood pressure (~60 mm Hg) in these animals.11

Acknowledgments

For technical assistance, the authors wish to thank Glenn Slocum (microscopic analysis), Christine Duris (immunohistochemistry), Lisa Henderson and Camille Torres (biochemical assays) of the Medical College of Wisconsin. David H Ellison (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland) and Pablo Ortiz (Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit) are greatly appreciated for providing antibodies. The authors are grateful to Justine Abais-Battad (Medical College of Wisconsin) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants HL108880 and HL122662 (to AS), HL82798 (to CM), HL116603 (to TSP), and DK105160 (to DVI), American Diabetes Association grant 1-15-BS-172, and American Heart Association grant 16EIA26720006 (to AS).

References

- 1. Cowley AW., Jr. Long-term control of arterial blood pressure. Physiol Rev 1992; 72: 231–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cowley AW., Jr. The genetic dissection of essential hypertension. Nat Rev Genet 2006; 7: 829–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cowley AW, Jr, Roman RJ. The role of the kidney in hypertension. JAMA 1996; 275: 1581–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moreno C, Kaldunski ML, Wang T, et al. Multiple blood pressure loci on rat chromosome 13 attenuate development of hypertension in the Dahl S hypertensive rat. Physiol Genomics 2007; 31: 228–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moreno C, Williams JM, Lu L, et al. Narrowing a region on rat chromosome 13 that protects against hypertension in Dahl SS-13BN congenic strains. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011; 300: H1530–H1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cowley AW, Jr., Moreno C, Jacob HJ, et al. Characterization of biological pathways associated with a 1.37 Mbp genomic region protective of hypertension in Dahl S rats. Physiol Genomics 2014; 46: 398–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rapp J, Wang S, Dene H. A genetic polymorphism in the renin gene of Dahl rats cosegregates with blood pressure. Science 1989; 243: 542–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiang J, Stec DE, Drummond H, et al. Transfer of a salt-resistant renin allele raises blood pressure in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension 1997; 29: 619–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. St Lezin EM, Pravenec M, Wong AL, et al. Effects of renin gene transfer on blood pressure and renin gene expression in a congenic strain of Dahl salt-resistant rats. J Clin Invest 1996; 97: 522–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ramkumar N, Stuart D, Rees S, et al. Collecting duct-specific knockout of renin attenuates angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2014; 307: F931–F938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moreno C, Hoffman M, Stodola TJ, et al. Creation and characterization of a renin knockout rat. Hypertension 2011; 57: 614–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roman RJ. Abnormal renal hemodynamics and pressure-natriuresis relationship in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol 1986; 251: F57–F65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pavlov TS, Ilatovskaya DV, Palygin O, et al. Implementing patch clamp and live fluorescence microscopy to monitor functional properties of freshly isolated PKD epithelium. J Vis Exp 2015; 103: e53035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pavlov TS, Levchenko V, O’Connor PM, et al. Deficiency of renal cortical EGF increases ENaC activity and contributes to salt-sensitive hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013; 24: 1053–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pavlov TS, Chahdi A, Ilatovskaya DV, et al. Endothelin-1 inhibits the epithelial Na+ channel through betaPix/14-3-3/Nedd4-2. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21: 833–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Masilamani S, Kim GH, Mitchell C, et al. Aldosterone-mediated regulation of ENaC alpha, beta, and gamma subunit proteins in rat kidney. J Clin Invest 1999; 104: R19–R23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bostanjoglo M, Reeves WB, Reilly RF, et al. 11Beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, mineralocorticoid receptor, and thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter expression by distal tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998; 9: 1347–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Terker AS, Yarbrough B, Ferdaus MZ, et al. et al. Direct and indirect mineralocorticoid effects determine distal salt transport. J Am Soc Nephrol. Epub ahead of print 28 December 2015. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.2015070815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haque MZ, Ares GR, Caceres PS, Ortiz PA. High salt differentially regulates surface NKCC2 expression in thick ascending limbs of Dahl salt-sensitive and salt-resistant rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2011; 300: F1096–F1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ares GR, Haque MZ, Delpire E, et al. Hyperphosphorylation of Na-K-2Cl cotransporter in thick ascending limbs of Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension 2012; 60: 1464–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Staruschenko A. Regulation of transport in the connecting tubule and cortical collecting duct. Compr Physiol 2012; 2: 1541–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lifton RP. Genetic determinants of human hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995; 92: 8545–8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ray EC, Kleyman TR. Cutting it out: ENaC processing in the human nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kobori H, Nishiyama A, Abe Y, et al. Enhancement of intrarenal angiotensinogen in Dahl salt-sensitive rats on high salt diet. Hypertension 2003; 41: 592–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mattson DL, Dwinell MR, Greene AS, et al. Chromosome substitution reveals the genetic basis of Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension and renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2008; 295: F837–F842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bayorh MA, Ganafa AA, Emmett N, et al. Alterations in aldosterone and angiotensin II levels in salt-induced hypertension. Clin ExpHypertens 2005; 27: 355–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, et al. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: From physiology to the pathobiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharmacol Rev 2007; 59: 251–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shibata S, Mu S, Kawarazaki H, et al. Rac1 GTPase in rodent kidneys is essential for salt-sensitive hypertension via a mineralocorticoid receptor-dependent pathway. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 3233–3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mamenko M, Zaika O, Prieto MC, et al. Chronic angiotensin II infusion drives extensive aldosterone-independent epithelial Na+ channel activation. Hypertension 2013; 62: 1111–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mamenko M, Zaika O, Ilatovskaya DV, et al. Angiotensin II increases activity of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) in the distal nephron additively to aldosterone. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 660–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mironova E, Bugaj V, Roos KP, et al. Aldosterone-independent regulation of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) by vasopressin in adrenalectomized mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109: 10095–10100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Velazquez H, Bartiss A, Bernstein P, et al. Adrenal steroids stimulate thiazide-sensitive NaCl transport by rat renal distal tubules. Am J Physiol 1996; 270: F211–F219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rozansky DJ, Cornwall T, Subramanya AR, et al. Aldosterone mediates activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter through an SGK1 and WNK4 signaling pathway. J Clin Invest 2009; 119: 2601–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim G-H, Masilamani S, Turner R, et al. The thiazide-sensitive Na–Cl cotransporter is an aldosterone-induced protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95: 14552–14557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tian Y, Riazi S, Khan O, et al. Renal ENaC subunit, Na-K-2Cl and Na-Cl cotransporter abundances in aged, water-restricted F344 x Brown Norway rats. Kidney Int 2006; 69: 304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sandberg MB, Riquier AD, Pihakaski-Maunsbach K, et al. ANG II provokes acute trafficking of distal tubule Na+Cl− cotransporter to apical membrane. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2007; 293: F662–F669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gurley SB, Riquier ADM, Schnermann J, et al. AT(1A) Angiotensin Receptors in the Renal Proximal Tubule Regulate Blood Pressure. Cell Metab 2011; 13: 469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. San-Cristobal P, Pacheco-Alvarez D, Richardson C, et al. Angiotensin II signaling increases activity of the renal Na-Cl cotransporter through a WNK4-SPAK-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 4384–4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eladari D, Chambrey R, Picard N, et al. Electroneutral absorption of NaCl by the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron: Implication for normal electrolytes homeostasis and blood pressure regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014; 71: 2879–2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ergonul Z, Frindt G, Palmer LG. Regulation of maturation and processing of ENaC subunits in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2006; 291: F683–F693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raff H, Gehrand A, Bruder ED, et al. Renin knockout rat: Control of adrenal aldosterone and corticosterone synthesis in vitro and adrenal gene expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2015; 308: R73–R77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]