Abstract

Although low bone mineral density (BMD) predicts fractures, there are postulated sex differences in the fracture ‘‘threshold.’’ Some studies demonstrate a higher mean BMD for men with fractures than for women, whereas others note similar absolute risk at the same level of BMD. Our objective was to test the preceding observations in the population-based Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMOS). We included participants 50+ years of age at baseline. Mean BMD in men was higher than in women among both fracture cases and noncases. Three methods of BMD normalization were compared in age-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models. In a model using the same reference population mean and standard deviation (SD), there were strong effects of age and total-hip BMD for prediction of fractures but no significant effect of sex [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78–1.20] for men versus women. In a model using sex-specific reference means but a common SD, an apparent sex difference emerged (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.54–0.81) for men versus women. The sex term in the second model counterbalanced the higher risk introduced by the lower normalized BMD in men. A third model using sex-specific reference means and SDs gave nearly identical results. Parallel results for the three methods of normalization were seen when adjusting for clinical risk factors, excluding antiresorptive users and considering death as a competing risk. We conclude that no adjustment for sex is necessary when using common reference data for both men and women, whereas using sex-specific reference data requires a substantial secondary adjustment for sex.

Keywords: FRACTURES, SEX, BONE MINERAL DENSITY, DUAL-ENERGY X-RAY ABSORPTIOMETRY

Introduction

Bone mineral density (BMD) assessment with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is well established in the diagnosis of osteoporosis and for fracture risk assessment in postmenopausal women.(1,2) The World Health Organization (WHO) recently has clarified diagnostic criteria for postmenopausal women by emphasizing a reference site (femoral neck) and reference population [white females aged 20 to 29 years based on the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III)].(3)

The diagnosis of osteoporosis in men is more controversial. Although DXA of the femoral neck predicts fractures with a gradient of risk in men similar to what is seen in women,(4) there is disagreement over whether the same diagnostic threshold should be used for men and women and whether the reference population should be based on female or male reference data. The most recent position from the WHO states that a similar cutoff value for femoral neck BMD should be used to define osteoporosis in women and men, namely, a BMD value 2.5 standard deviations (SD) or more below the average for young-adult women (ie, a T-score of −2.5 or lower). Other groups have recommended sex-specific reference populations.(5–7) Arguments in favor of the former focus on cohort studies showing that absolute fracture risk in men and women is similar at the same absolute level of BMD (in g/cm2).(4,8–10) Arguments to support the latter focus on reports that men fracture at a higher level of BMD than women.(11–13) These two sets of observations are often presented as in conflict.(14)

A recent review by Khosla and colleagues(15) concluded that the most appropriate definition for osteoporosis in men, in the absence of fractures, was a major unresolved issue and should be the focus of future research. This issue was specifically addressed in the population-based Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMOS) cohort, one of the first population-based cohorts to include both men and women.

Methods

Study population

The study sample was selected from participants in an ongoing population-based longitudinal cohort study, the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMOS). We included all CaMOS participants aged 50 years and over at study entry for whom follow-up data and BMD measurements were available.

The methodologic details of CaMOS have been described elsewhere.(16) Briefly, eligible participants were at least 25 years old at the start of the study, lived within a 50-km radius of one of nine Canadian cities (St. John, Halifax, Quebec City, Toronto, Hamilton, Kingston, Saskatoon, Calgary, and Vancouver), and were able to converse in English, French, or Chinese (Toronto and Vancouver). Households were randomly selected from a list of residential phone numbers, and participants were randomly selected from eligible household members using a standard protocol. Of those selected, 42% agreed to participate. Ethics approval was granted through McGill University and the appropriate ethics review boards for each participating center. All participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Data collection

Participants completed a standardized interviewer-administered questionnaire (CaMOS questionnaire © 1995) at baseline, which assessed demographics, general health, nutrition, medication use, and medical history. The questionnaire was designed to capture detailed information about risk factors for fractures, including information about prior fractures and, as such, assessed all previous fractures (ie, fracture site, date, and circumstances), family history of osteoporosis/fractures, and falls in the past month. Participants had a baseline clinical assessment that included measurement of height, weight, and BMD.

Bone mineral density measurements

BMD was measured at the lumbar spine (L1–L4) and proximal femur. Seven centers used Hologic densitometers (Hologic Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), and two used GE Lunar densitometers (GE Lunar, Madison, WI, USA). All Lunar measurements were converted to equivalent Hologic values using standard reference formulas.(17) All densitometers were cross-calibrated using a European spine phantom circulated among study centers. A more detailed description of BMD quality control appears elsewhere.(18)

Fracture assessment

Self-reported incident clinical fractures were identified by yearly postal questionnaire or at the scheduled interval for reassessment (third, fifth, and tenth year after study entry). Confirmation and further information concerning the fracture were gathered using a structured interview that included date, fracture site, circumstances leading to the fracture, and medical treatment. Participants who reported fractures were asked for consent to contact the treating physician or hospital for verification and for acquisition of further details. Fractures that occurred without trauma or from a fall of standing height or less were considered to be low-trauma fractures. For this analysis, all low-trauma clinical fractures that occurred up to the year 10 annual follow-up were included, with the exception of fractures of the skull, face, hands, and feet.

Statistical methods

We used the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate absolute fracture risk probability to 10 years in men and women, supplemented with a series of Cox proportional-hazards models of fracture risk in men and women using three different methods of BMD normalization. Age, sex, and total-hip BMD were included as covariates in all models. We used NHANES III non-Hispanic whites (ages 20 to 29 years) as the reference population for all models.(3) In model 1, BMD was centered using a common reference mean and SD based on the NHANES III women. In model 2, BMD was centered separately using a sex-specific mean, but we still used the SD derived from women only. In model 3, BMD was centered separately using a sex-specific mean and a sex-specific SD, resulting in a sex-specific NHANES III T-score. Entry into the model was time of study enrollment, and exit from the model was the first of the following: 10-year follow-up, fracture outcome, or loss to follow-up. Because men and women have different underlying mortality risk, we considered two options in the case of death: as censored (base model) and as a competing risk (all other models). We excluded all BMD outliers for a given sex and age category by examining box plots, histograms, and normal probability plots. To more closely match the BMD ranges for men and women, we further excluded those who had BMD outside the distribution range of the same age category for the opposite sex, that is, men with higher BMD than women of the same age and women with lower BMD than men of the same age. We assessed linearity, proportional hazards, and statistical interactions by formal tests and by looking at survival-curve plots (log-log) and residual plots.

There were notable differences between men and women in clinical risk factors for fractures and the use of antiresorptive therapy. In secondary analysis, we repeated the analysis adjusting for clinical risk factors, excluding all antiresorptive users and limiting the fracture sites to the hip, spine, wrist, and humerus. The clinical risk factors were body mass index, prior low-trauma fracture after age 50, parental fracture, alcohol intake, current smoking, rheumatoid arthritis, and glucocorticoid use because these are part of the WHO fracture risk assessment (FRAX) paradigm.(19) We also repeated all the preceding analyses using femoral neck BMD rather than total-hip BMD. The analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Stata Version 9.2 (Stata, Inc., College Station, TX, USA) for Windows.

Results

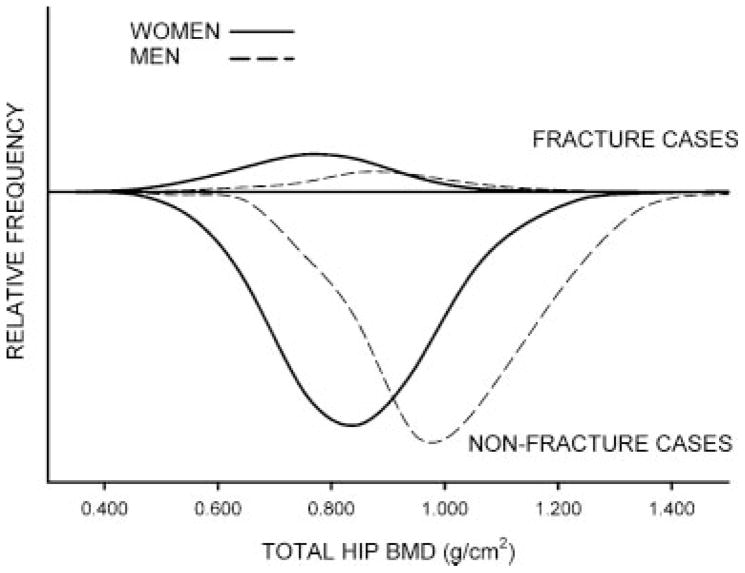

There were 4700 eligible women and 1874 eligible men with mean follow-up of 8.2 and 8.1 years, respectively. A total of 614 women and 125 men had at least one clinical low-trauma fracture within 10 years, and the overall 10-year fracture risk was 15.0% [95% confidence interval (CI) 13.9–16.1] for women and 7.9% (95% CI 6.7–9.4) for men. Men had higher mean total-hip BMD values than women (difference 0.158 g/cm2, 95% CI 0.150–0.166) regardless of fracture status. For those with incident low-trauma fractures, the mean total-hip BMD was 0.122 g/cm2 (95% CI 0.095–0.150) higher in men than in women, but mean total-hip BMD was 0.155 g/cm2 (95% CI 0.147–0.163) higher in men without fractures. Finally, baseline use of antiresorptive therapy was relatively common in women (29.4% were users), whereas it was very rare in men (0.1% were users). The distribution of baseline total-hip BMD by sex and fracture status is shown in Fig. 1 and demonstrates the lower overall fracture risk for men (smaller area under the curve for fracture cases), as would be expected given their higher BMD values. The figure also demonstrates that men had, on average, higher baseline BMD values both among those with incident fracture and among those without incident fracture, as noted by observing that the distribution and peaks for men (fracture and nonfracture) were offset to the right of the distribution of peaks for women (fracture and nonfracture).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of baseline total-hip BMD by sex (solid line for women, broken line for men) and incident 10-year fracture status (low-trauma fracture cases plotted above the x axis, fracture-free cases plotted below to the x axis). Relative frequencies are scaled to the total number of women and men.

After excluding BMD outliers, we were left with 4359 women (526 with clinical low-trauma fractures) and 1628 men (117 with fractures). The exclusion of outliers decreased the mean total-hip BMD difference between men and women to 0.112 g/cm2 (95% CI 0.105–0.119). The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample (Women and Men Ages 50 Years and Oldera)

| Women (n = 4539) | Men (n = 1628) | Difference | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total-hip BMD (g/cm2) | 0.852 (0.849, 0.856) | 0.964 (0.958, 0.970) | 0.112 (0.105, 0.119) | <.0001 |

| Femoral neck BMD (g/cm2) | 0.699 (0.696, 0.702) | 0.766 (0.761, 0.771) | 0.067 (0.061, 0.073) | <.0001 |

| Age (years) | 65.5 (65.2, 65.7) | 64.9 (64.4, 65.3) | −0.6 (−1.1, −0.1) | .022 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.4 (27.2, 27.5) | 27.0 (26.8, 27.2) | −0.4 (−0.6, −0.2) | .0005 |

| Alcohol (units/day) | 0.30 (0.28, 0.31) | 0.75 (0.69, 0.82) | 0.45 (0.39, 0.51) | <.0001 |

| Prior low-trauma fracture after age 50 | 10.4% (9.4%, 11.3%) | 5.2% (4.1%, 6.2%) | −5.2% (−6.8%, −3.6%) | <.0001 |

| Parental fracture history | 35.3% (33.8%, 36.8%) | 31.2% (28.8%, 33.6%) | −4.1% (−6.9%, −1.3%) | .0045 |

| Current smoker | 12.9% (11.9%, 13.8%) | 18.9% (17.0%, 20.8%) | 6.0% (4.0%, 8.0%) | <.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 6.8% (6.1%, 7.6%) | 5.2% (4.1%, 6.3%) | −1.6% (−3.0%, −0.0%) | .015 |

| Glucocorticoids | 1.2% (0.9%, 1.5%) | 1.3% (0.7%, 1.8%) | 0.1% (−0.5%, 0.7%) | .765 |

| Antiresorptive treatment | 29.4% (28.1%, 30.8%) | 0.1% (0%–0.3%) | −29.3% (−31.5%, −27.1%) | <.0001 |

Note: Data are mean or percentage with corresponding 95% confidence interval in parentheses.

Excludes outliers with BMD outside the range for the same age group from the opposite sex.

A summary of all analyses based on total-hip BMD is presented in Table 2. To assess skeletal fragility alone, we first considered models where death was censored. In model 1, where total-hip BMD was scaled using a common mean and SD for both men and women, there were strong effects of age (hazards ratio (HR) = 1.49 per decade increase, 95% CI 1.35–1.64] and total-hip BMD (HR = 1.60 per SD increase, 95% CI 1.46–1.75) for prediction of incident fractures, but no significant effect of sex (HR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.78–1.20) for men versus women. In model 2, which used sex-specific means, we found a similar effect of age and BMD, but an apparent sex difference emerged, with men having lower risk (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.54–0.81) compared with women. In this model, the normalized BMD scores for men were 0.63 SD lower than those for women with the same absolute BMD because the reference mean BMD was higher in men. The higher risk introduced by the lower normalized BMD was approximately offset in the model by the sex term, indicating lower risk in men. The comparison of men and women for model 3 was the same as in model 2. The similarity between model 2 and model 3 suggests that the apparent differences between men and women are attributable to having sex-specific reference means and not attributable to having sex-specific SD values.

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios (HRs) for Low-Trauma Fracture Using Different Total-Hip BMD Normalization Methods

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base model (censored death) | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.49 (1.35–1.64) | 1.49 (1.35–1.64) | 1.49 (1.35–1.64) |

| Total-hip BMD (per SD decrease) | 1.60 (1.46–1.75) | 1.60 (1.46–1.75) | 1.61 (1.47–1.77) |

| Sex (men versus women) | 0.97 (0.78–1.20) | 0.66 (0.54–0.81) | 0.71 (0.58–0.87) |

| With death as competing risk | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.37 (1.24–1.50) | 1.37 (1.24–1.50) | 1.37 (1.24–1.50) |

| Total-hip BMD (per SD decrease) | 1.59 (1.45–1.74) | 1.59 (1.45–1.74) | 1.60 (1.46–1.76) |

| Sex (men versus women) | 0.90 (0.73–1.12) | 0.62 (0.51–0.76) | 0.67 (0.55–0.83) |

| With adjustment for clinical risk factors (death as competing risk) | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.27 (1.14–1.41) | 1.27 (1.14–1.41) | 1.27 (1.14–1.41) |

| Total-hip BMD (per SD decrease) | 1.62 (1.46–1.80) | 1.62 (1.46–1.80) | 1.64 (1.47–1.82) |

| Sex (men versus women) | 0.90 (0.70–1.14) | 0.61 (0.48–0.76) | 0.66 (0.52–0.83) |

| With exclusion of those taking antiresorptive therapy (death as competing risk) | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.34 (1.20–1.48) | 1.34 (1.20–1.48) | 1.34 (1.20–1.49) |

| Total-hip BMD (per SD decrease) | 1.54 (1.39–1.71) | 1.54 (1.39–1.71) | 1.56 (1.40–1.73) |

| Sex (men versus women) | 0.86 (0.69–1.08) | 0.61 (0.49–0.75) | 0.65 (0.53–0.81) |

| With fractures limited to hip, spine, humerus, and wrist (death as competing risk) | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.43 (1.28–1.60) | 1.43 (1.28–1.60) | 1.43 (1.28–1.60) |

| Total-hip BMD (per SD decrease) | 1.56 (1.40–1.73) | 1.56 (1.40–1.73) | 1.56 (1.40–1.75) |

| Sex (men versus women) | 0.75 (0.57–0.98) | 0.52 (0.41–0.67) | 0.56 (0.44–0.73) |

Note: Data are from Cox proportional hazards models with corresponding 95% confidence interval in parentheses. NHANES III white (ages 20 to 29 years) reference data used. Model 1: female as reference for both sexes; model 2: sex-specific mean, female SD; model 3: sex-specific mean and sex-specific SD.

We then considered a series of models where death was a competing risk. In model 1, again there was no significant effect of sex (HR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.73–1.12), but there still were strong effects of total-hip BMD and age. For the two models with sex-specific means and death as a competing risk, we again found apparent sex differences with HR = 0.62 (95% CI 0.51–0.76) in model 2 and HR = 0.67 (95% CI 0.55–0.83) in model 3. The higher mortality in men (versus women) and older age groups (versus younger age groups) account for the larger decrease in fracture risk in these groups when death is considered as a competing risk.

To discern whether the results were affected by sex differences in other risk factors, we also performed analyses with adjustments for clinical risk factors. In model 1, again there was no significant effect of sex (HR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.70–1.14). With sex-specific reference data, we again found very strong sex effects for men compared with women in model 2 (HR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.48–0.76) and in model 3 (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.52–0.83). Thus the clinical risk factors did not materially affect the apparent sex differences introduced by having sex-specific reference means. Likewise, even though there was a marked difference in the use of antiresorptive therapy between men and women, we found similar results after excluding all those taking antiresorptive therapy. Finally, we restricted fracture outcomes to fractures at the hip, spine, humerus, and wrist (death as a competing risk). For this outcome, men had an overall lower risk of fracture (HR = 0.75, 95% CI 0.57–0.98) when using a common reference mean and SD (model 1). However, using a sex-specific reference mean amplified this difference, resulting in men having roughly half the risk of women.

Femoral neck BMD was studied in a secondary series of analyses (Table 3). The major difference from the analyses based on total-hip BMD is that men had significantly lower fracture risk than women in all models with common reference data (model 1) except for the base model with censored death (HR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.67–1.02). Once again, using sex-specific reference data amplified the sex effect, resulting in men having roughly half the risk of women.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios (HRs) for Low-Trauma Fracture Using Different Femoral Neck BMD Normalization Methods

| HR (95% CI) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base model (censored death) | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.55 (1.41–1.71) | 1.55 (1.41–1.71) | 1.55 (1.41–1.71) |

| Femoral neck BMD (per SD decrease) | 1.69 (1.52–1.88) | 1.69 (1.52–1.88) | 1.70 (1.52–1.90) |

| Sex (men versus women) | 0.83 (0.67–1.02) | 0.59 (0.49–0.72) | 0.67 (0.55–0.81) |

| With death as competing risk | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.42 (1.29–1.56) | 1.42 (1.29–1.56) | 1.42 (1.29–1.56) |

| Femoral neck BMD (per SD decrease) | 1.67 (1.50–1.86) | 1.67 (1.50–1.86) | 1.68 (1.51–1.88) |

| Sex (men versus women) | 0.78 (0.63–0.96) | 0.56 (0.46–0.68) | 0.63 (0.52–0.77) |

| With adjustment for clinical risk factors (death as competing risk) | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.34 (1.20–1.49) | 1.34 (1.20–1.49) | 1.34 (1.20–1.49) |

| Femoral neck BMD (per SD decrease) | 1.68 (1.48–1.89) | 1.68 (1.48–1.89) | 1.68 (1.49–1.91) |

| Sex (men versus women) | 0.76 (0.60–0.96) | 0.55 (0.44–0.68) | 0.61 (0.49–0.77) |

| With exclusion of those taking antiresorptive therapy (death as competing risk) | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.37 (1.23–1.52) | 1.37 (1.23–1.52) | 1.38 (1.24–1.53) |

| Femoral neck BMD (per SD decrease) | 1.63 (1.45–1.84) | 1.63 (1.45–1.84) | 1.64 (1.45–1.86) |

| Sex (men versus women) | 0.75 (0.60–0.93) | 0.55 (0.45–0.67) | 0.61 (0.50–0.75) |

| With fractures limited to hip, spine, humerus, and wrist (death as competing risk) | |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.51 (1.35–1.69) | 1.51 (1.35–1.69) | 1.51 (1.35–1.69) |

| Femoral neck BMD (per SD decrease) | 1.61 (1.42–1.83) | 1.61 (1.42–1.83) | 1.62 (1.42–1.84) |

| Sex (men versus women) | 0.63 (0.49–0.82) | 0.47 (0.36–0.60) | 0.52 (0.41–0.67) |

Note: Data are from Cox proportional hazards models with corresponding 95% confidence interval in parentheses. NHANES III white (ages 20 to 29 years) reference data used. Model 1: female as reference for both sexes; model 2: sex-specific mean, female SD; model 3: sex-specific mean and sex-specific SD.

Discussion

We found that the 10-year risk of fracture was considerably lower in men (approximately half) than in women. As expected, mean BMD was greater in men than in women overall and when stratified by fracture status. BMD measurements are areal measurements rather than true density, and hence a higher BMD is expected in men owing to their larger bone size. The fact that men with low-trauma fractures had higher mean BMD values than women with low-trauma fractures did not indicate a different fracture ‘‘threshold’’ or higher risk for a given level of absolute BMD because sex was not significantly associated with fracture risk when adjusted for both age and absolute BMD. The finding of higher mean BMD in men with (or without) low-trauma fracture therefore is attributed to the sex-related difference in BMD distribution rather than to an intrinsic difference in skeletal fragility. Indeed, when sex-specific reference data were used for BMD normalization, this introduced an apparent sex difference (men at lower risk than women) with an effect size approximately counterbalancing the change in normalized BMD score (lower for men than for women for a specified absolute BMD level). The least complicated model for describing fracture risk therefore is to use the same reference data for BMD normalization in both men and women. A convenient (albeit imperfect) analogy can be found in the sizing of athletic shoes for men and women, which is defined in terms of foot length in some countries: Male size = length (cm) −18; female size = length (cm) −17. This reflects the fact that men have, on average, longer feet than women, although there is no inherent reason for making the distinction if it is the size of the foot that really matters in shoe fitting (ignoring considerations of style or width). A man and a women with a foot length of 28 cm could equally wear size 10 men’s or size 11 women’s athletic shoes. Life might be simpler for shoe retailers if there were just one shoe sizing system for both sexes.

Some have suggested that the finding of higher BMD values in men with fractures is at odds with equal fracture risk for the same level of BMD.(5) Our study demonstrates that these findings are mutually compatible and demonstrable in the same cohort. The Rotterdam Study found that the rates of fracture in men and women were similar for equivalent absolute BMD,(9,20) and this has been observed in other cohorts.(8,10) The WHO coordinating center has reviewed the available data and suggested that a common (sex-independent) reference database be used for T-score generation,(4) and for the femoral neck, the recommended database is NHANES III for young white females.(3)

As fracture risk assessment moves globally from a T-score-based approach to absolute 10-year fracture risk using the WHO fracture risk assessment (FRAX) tool, controversies regarding choice of BMD reference population become less critical. FRAX tools could be calibrated equally well with sex-matched or sex-independent T-scores. The only relevance then relates to diagnostic categorization based on a specific T-score cutoff (historically −2.5 for the diagnosis of osteoporosis). Using sex-specific reference data will categorize more men as having osteoporosis despite lower fracture risk than women at the same T-score cutoff. Although this may have some advantages in sensitizing practitioners to the importance of osteoporosis in men, it does not specifically address the large osteoporosis care gap present among men.(21) For example, men who have sustained an obvious fragility fracture (and who have osteoporosis on clinical grounds) are rarely evaluated for osteoporosis, and this cannot be corrected simply by using a different reference population.(21,22)

When FRAX or other absolute fracture assessment systems are used in men, it is essential to clearly indicate the BMD normalization procedure to be used. To avoid confusion, the latest Web-based version of the FRAX tool now allows for absolute BMD to be entered directly (with equipment manufacture designation). Software upgrades on DXA equipment calculate the FRAX T-score internally based on the appropriate normalization requirements independent of how sex and ethnicity are entered.

Limitations to this study include the relatively small number of men and, by extension, the relatively small number of men with fractures. This results in relatively wide confidence intervals for the effect of sex in the regression models. We also had limited power to conduct detailed testing for interactions, and this study does not preclude sex differences in the gradient of risk. The gradient of risk is partially determined by those with BMD values that are not comparable with those of the opposite sex. The exclusion of outliers in this analysis precludes assessment of interactions determined by those with BMD values unmatched by similar BMD values in the opposite sex. Significant age-BMD and sex-BMD interactions have been reported by others.(23,24) Cummings and colleagues reported that the risk of nonvertebral fracture was substantially lower in men than in women for all T-scores of hip BMD regardless of whether sex-specific or female reference values were used.(24) We were only able to observe this when death was treated as a competing risk, and this was due to known sex differences in survival rather than a difference in underlying bone fragility.

In summary, we have shown that there is no inherent contradiction between a similar fracture risk in men and women at a given level of BMD and the observed sex differences in BMD among fracture cases. In our cohort, sex-specific normalization of BMD values resulted in a more complicated model that must include a counterbalancing sex term. The implication is that a common (sex-independent) reference database is appropriate for both men and women and that existing absolute BMD thresholds, based on data from postmenopausal women, are associated with similar fracture incidence in men and thus result in a similar risk interpretation.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in CaMOS, whose careful responses and attendance made this analysis possible.

The CaMOS Research Group includes David Goltzman (co-principal investigator, McGill University), Nancy Kreiger (co-principal investigator, Toronto), Alan Tenenhouse (principal investigator emeritus, Toronto); CaMOS Coordinating Centre, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Suzette Poliquin (national coordinator), Suzanne Godmaire (research assistant), and Claudie Berger (study statistician); Memorial University, St John, Newfoundland, Canada: Carol Joyce (director), Christopher Kovacs (codirector), and Emma Sheppard (coordinator); Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Susan Kirkland, Stephanie Kaiser (codirectors), and Barbara Stanfield (coordinator); Laval University, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada: Jacques P Brown (director), Louis Bessette (codirector), and Marc Gendreau (coordinator); Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada: Tassos Anastassiades (director), Tanveer Towheed (codirector), and Barbara Matthews (coordinator); University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Bob Josse (director), Sophie A Jamal (codirector), Tim Murray (past director), and Barbara Gardner-Bray (coordinator); McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: Jonathan D Adachi (director), Alexandra Papaioannou (codirector), and Laura Pickard (coordinator); University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Wojciech P Olszynski (director), K Shawn Davison (codirector), and Jola Thingvold (coordinator); University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada: David A Hanley (director) and Jane Allan (coordinator); and University British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Jerilynn C Prior (director), Milan Patel (codirector), Yvette Vigna (coordinator), and Brian C. Lentle (radiologist).

The Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Merck Frosst Canada, Ltd., Eli Lilly Canada, Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and the Alliance for Better Bone Health: Sanofi-Aventis, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals Canada, Inc., Amgen, Inc., the Dairy Farmers of Canada, and the Arthritis Society.

Footnotes

Disclosures

WDL has received speaker fees and unrestricted research grants from Merck Frosst Canada, Ltd.; unrestricted research grants from Sanofi-Aventis, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals Canada, Inc., Novartis, Amgen Pharmaceuticals Canada, Inc., Innovus 3M, and Genzyme Canada; and has served on advisory boards for Genzyme Canada, Novartis, and Amgen Pharmaceuticals Canada, Inc. DG serves as a consultant for Eli Lily, Novartis, Merck, Proctor & Gamble, and Amgen. CSK serves as a consultant and has received grants from Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Proctor & Gamble, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Novo Nordisk, and Macrogenics. RJ serves as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer Corporation, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Proctor & Gamble, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, and Wyeth-Ayerst. DAH serves as a consultant and has received grants from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Proctor & Gamble, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Wyeth-Ayerst, Nycomed, and Paladin. KSD has served as an advisory board member and received honoraria from Amgen, Merck, Proctor & Gamble, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier. TA has received honoraria from Merck, Proctor & Gamble, Schering Plough, and Servier. TT has received grant support from Abbott Laboratories and Sanofi-Aventis and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Sanofi-Aventis. Stephanie Kaiser has served as an advisory board member and received honoraria from Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Proctor & Gamble, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, and Wyeth-Ayerst. The rest of the authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cummings SR, Bates D, Black DM. Clinical use of bone densitometry: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:1889–1897. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanis JA, Melton LJ, III, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:1137–1141. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ, III, Khaltaev N. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone. 2008;42:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, De Laet C, Mellstrom D. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and fracture threshold in men. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69:218–221. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-1046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binkley NC, Schmeer P, Wasnich RD, Lenchik L. What are the criteria by which a densitometric diagnosis of osteoporosis can be made in males and non-Caucasians? J Clin Densitom. 2002;5:S19–27. doi: 10.1385/jcd:5:3s:s19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewiecki EM, Watts NB, McClung MR, et al. Official positions of the international society for clinical densitometry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3651–3655. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siminoski K, Leslie WD, Frame H, et al. Recommendations for bone mineral density reporting in Canada. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2005;56:178–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The EPOS Study Group. The relationship between bone density and incident vertebral fracture in men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:2214–2221. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.12.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Laet CE, van der KM, Hofman A, Pols HA. Osteoporosis in men and women: a story about bone mineral density thresholds and hip fracture risk. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:2231–2236. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.12.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnell O, Kanis J, Gullberg G. Mortality, morbidity, and assessment of fracture risk in male osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69:182–184. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-1045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orwoll E. Assessing bone density in men. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1867–1870. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.10.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen T, Sambrook P, Kelly P, et al. Prediction of osteoporotic fractures by postural instability and bone density. BMJ. 1993;307:1111–1115. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6912.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenspan SL, Myers ER, Maitland LA, Kido TH, Krasnow MB, Hayes WC. Trochanteric bone mineral density is associated with type of hip fracture in the elderly. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:1889–1894. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650091208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebeling PR. Clinical practice. Osteoporosis in men. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1474–1482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0707217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khosla S, Amin S, Orwoll E. Osteoporosis in men. Endocr Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreiger N, Tenenhouse A, Joseph L, et al. Research notes: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos) - background, rationale, methods. Can J Aging. 1999;18:376–387. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genant HK. Universal standardization for dual X-ray absorptiometry: patient and phantom cross-calibration results. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:997–998. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger C, Langsetmo L, Joseph L, et al. Change in bone mineral density as a function of age in women and men and association with the use of antiresorptive agents. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;178:1660–1668. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, et al. The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0343-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Laet CE, Van Hout BA, Burger H, Weel AE, Hofman A, Pols HA. Hip fracture prediction in elderly men and women: validation in the Rotterdam study. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1587–1593. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.10.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papaioannou A, Kennedy C, Ioannidis G, et al. The osteoporosis care gap in men with fragility fractures: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:581–587. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0483-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiebzak GM, Beinart GA, Perser K, Ambrose CG, Siff SJ, Heggeness MH. Undertreatment of osteoporosis in men with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2217–2222. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.19.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, et al. Predictive value of BMD for hip and other fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1185–1194. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cummings SR, Cawthon PM, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Fink HA, Orwoll ES. BMD and risk of hip and nonvertebral fractures in older men: a prospective study and comparison with older women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1550–1556. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]