Abstract

Eosinophils are native to the healthy gastrointestinal tract, and are associated with inflammatory diseases likely triggered by exposure to food allergens (e.g. food allergies and eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders). In models of allergic respiratory diseases and in vitro studies, direct antigen engagement elicits eosinophil effector functions including degranulation and antigen presentation. However, it was not known whether intestinal tissue eosinophils that are separated from luminal food antigens by a columnar epithelium might similarly engage food antigens. Using an intestinal ligated loop model in mice, here we determined that resident intestinal eosinophils acquire antigen from the lumen of antigen-sensitized but not naïve mice in vivo. Antigen acquisition was immunoglobulin-dependent; intestinal eosinophils were unable to acquire antigen in sensitized immunoglobulin-deficient mice, and passive immunization with immune serum or antigen-specific IgG was sufficient to enable intestinal eosinophils in otherwise naïve mice to acquire antigen in vivo. Intestinal eosinophils expressed low affinity IgG receptors, and the activating receptor FcγRIII was necessary for immunoglobulin-mediated acquisition of antigens by isolated intestinal eosinophils in vitro. Our combined data suggest that intestinal eosinophils acquire lumen-derived food antigens in sensitized mice via FcγRIII antigen focusing, and may therefore participate in antigen-driven secondary immune responses to oral antigens.

Introduction

Eosinophils are innate immune cells that home naturally to all regions of the gastrointestinal tract except the esophagus. Numbers of intestinal eosinophils are further increased in several inflammatory diseases including food allergies (1), a group of idiopathic diseases collectively identified as eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs)(2), and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs)(3, 4). In food allergy, tissue eosinophils are activated following intestinal allergen provocation (5), and in IBDs increased expression of eosinophil-derived granule proteins in lavage or feces has been associated with disease activity (6). Eosinophils had been considered solely end-stage effector cells in helminth infections and allergic diseases. However, accumulating evidence from allergic diseases demonstrates eosinophils are multifaceted, participating in a number of processes from immunomodulation to tissue repair and remodeling (7-10). Moreover, specific physiological functions of eosinophils that reside within tissue niches are emerging, i.e. metabolic roles for adipose tissue eosinophils (11), tissue repair in injured muscle (12), and plasma cell maintenance by bone marrow eosinophils(13, 14). Likewise, new studies in eosinophil-deficient mice implicate intestinal eosinophils in the maintenance of IgA+ plasma cells (15, 16), oral tolerance (16), and activating dendritic cells to initiate primary immunity (17).

Food allergies and EGIDs are triggered by secondary exposure to food antigens; however, if and how eosinophils residing within intestine tissues can engage with antigens was unknown. Eosinophils engage free antigen directly within the airway lumen in models of allergic airway diseases. Eosinophils can pinocytose, process and present free antigens to naïve and activated CD4+ T cells (thereby functioning as antigen presenting cells (18-20)). In addition, in vitro eosinophils exposed to antibody:antigen immune complexes exhibit enhanced survival and secretion of granule proteins and reactive oxygen species (21-25). It had not been known whether eosinophils native to the intestinal lamina propria and physically separated from luminal food antigens by a columnar epithelium, might similarly engage soluble food antigens.

Antigen is actively transported into intestinal immune inductive sites (i.e. Peyer's patches and isolated lymphoid follicles) through M cells present within the overlying follicle-associated epithelum (26). Soluble protein antigens can also access the lamina propria beneath villous epithelium through goblet cell-associated antigen passages (GAPs)(27), and dendritic cells may extend dendrites paracellularly to directly sample lumen contents (28, 29). In humans lumen-derived antigens are also actively transported across villous epithelium via neonatal Fc receptors (FcRn)(30), although FcRn is not expressed in the intestine of adult rodents (31). Here we used an intestinal loop model to determine whether lamina propria eosinophils within the small intestine access lumen-derived antigen in vivo. Our data demonstrate that despite their capacity to readily pinocytose free antigen, intestinal eosinophils do not access antigen from the lumen in naïve mice. However, in allergen-sensitized mice, or in mice passively immunized with immune serum, intestinal eosinophils acquire lumen-derived antigens. Acquisition of lumen-derived antigens by tissue-resident eosinophils was restricted to the sensitizing antigen and required antigen-specific IgG and eosinophil-expressed Fc gamma receptor III (FcγRIII). These data suggest that FcγRIII-mediated antigen focusing enables resident intestinal eosinophils to capture lumen-derived antigen in secondary immunity in vivo, and provide a direct mechanistic link between humoral adaptive immunity and resident intestinal eosinophils.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River, Jh mice (BALB/c background) were purchased from Taconic, and Fcgr3tm1Sjv-/- mice (C57BL/6 background) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. dblGATA1-/- mice (BALB/c background) were bred in-house. All mice were housed in microisolator cages in a specific pathogen-free facility at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). IgE-/- mice and WT siblings on the BALB/c background were provided by Dr. Hans Oettgen's laboratory at Boston Children's Hospital. All animal care and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the BIDMC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Sensitization to OVA and BSA

For OVA/alum sensitization, 6-8 week old mice were sensitized i.p. with 0.04 mg OVA (Grade VI; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) mixed with 0.4 mg aluminum hydroxide and 0.4 mg magnesium hydroxide (Imject; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) in sterile PBS on days 0, 7, and 14. For BSA/alum sensitization 0.04 mg BSA (Grade V; Sigma-Aldrich) was used in place of OVA.

Intestinal Loops

Ligated intestinal loop surgery was performed as described (32) in naïve or OVA- or BSA-sensitized (day 21) mice. Briefly, intestinal loops were created by tying off two segments of small intestine (approximately 5 cm each) adjacent to the cecum with sterile suture, accessed through a small incision in the abdomen of isoflurane-anesthetized mice. Fluorescently labeled (Alexa 488 or Alexa 647) OVA and/or BSA (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) diluted in PBS was injected into the lumen of each loop (20 μg in 200 μL per loop) with a sterile syringe and needle. As a control, non-labeled OVA, non-labeled BSA, or PBS alone was injected into loops in a second mouse. The peritoneum and skin were closed in one layer with sterile suture, and mice maintained under anesthesia for an additional 45 minutes. After 45 min intestinal loops were harvested and intestinal cells were isolated.

Intestinal Cell Isolation

Total small intestinal cells were isolated as described (33). In brief, Peyer's patches were removed, and the intestine was flushed with CMF buffer (5% FBS, 1 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM NaHCO3 in HBSS-/-), opened longitudinally, gently wiped to remove mucus, and cut into 0.5 cm long pieces. Pieces were then washed and shaken (300 rpm, 37°C in an Innova 4000 incubator shaker, New Brunswick Scientific, Ensfield, CT) in DTT buffer (1 mM DL-dithiothreitol, 10% FBS, 1 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM NaHCO3 in HBSS-/-) for 2 × 20 min, and supernatants containing intraepithelial (IE) cells were recovered. Intestinal pieces were then shaken with EDTA buffer for 2 × 30 min (1.3 mM EDTA, 1× pen-strep in HBSS-/-), and supernatants containing epithelial cells were discarded. Lamina propria (LP) cells were isolated by shaking remaining intestinal tissue with collagenase buffer (175 U/mL collagenase, 10% FBS, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1× pen-strep in RPMI 1640 with L-glutamine and 25 mM HEPES) for 30 min and mashing it through a 70 μm cell strainer. IE and LP cells were further purified by discontinuous Percoll gradient centrifugation (44% and 67%) and combined (total intestinal cells) or analyzed separately, as indicated.

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting

Non-permeabilized cells were stained for flow cytometry, and data were acquired using a BD LSRII (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). For cell sorting, unfixed cells were sorted using a FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences). Compensations were performed using stained ArC amine reactive beads, AbC anti-rat/hamster beads, and AbC capture beads (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA).

Flow Cytometry Antibodies

PE-Cy7 rat anti-mouse CD45 clone 30-F11, PE rat anti-mouse Siglec-F clone E50-2440, Alexa Fluor 647 rat anti-mouse CD193 (CCR3), and their relevant isotype controls were purchased from BD Biosciences. FITC anti-mouse CD11c clone N418, APC anti-mouse/human CD11b clone M1/70, APC anti-mouse CD16/32 clone 93, APC anti-mouse FcεRIα clone MAR-1, APC anti-mouse CD23 clone B3B4, APC anti-mouse CD64 clone X54-5/7.1, and their relevant isotype controls were purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Aqua fluorescent reactive dye for live/dead labeling was purchased from Life Technologies.

Immunocytochemistry

Cytospins of sorted eosinophils were fixed with Zamboni's fixative. Cells were permeabilized with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS, endogenous peroxidases were quenched with 3% H2O2, cells were blocked with 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS, and then cells were incubated overnight in 2 μg/mL rat anti-MBP clone MT-14.7.3 (a gift from the labs of Nancy and Jamie Lee) or 2 μg/mL rat IgG in 1.5% NGS in PBS. Cells were then stained with 2 μg/mL biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in 1.5% NGS in PBS for 1 hr at room temperature. Peroxidase enzyme was bound to biotin using Vectastain ABC (Vector Laboratories) and staining was developed using Vector NovaRed substrate.

Serum Collection, IgG Isolation, and Passive Immunization

Peripheral blood was obtained via cardiac puncture in naive, OVA-sensitized, or BSA-sensitized mice (day 21) anesthetized with isoflurane. Blood was allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min before centrifuging at 2000×g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected as serum and stored at -80°C. IgG was isolated from the serum of OVA-sensitized mice following the elution protocol for GE Healthcare Protein G HP SpinTrap Columns (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Isolated IgG was brought up to the original volume of serum added to the column with PBS. 200 μL of serum or IgG isolated from serum was administered IP to naïve BALB/c mice 24 h prior to intestinal loop surgery.

ELISAs for Antigen-specific Immunoglobulins

EIA/RIA 96 well half-area plates (Corning, Corning, NY) were coated with 250 ng OVA or BSA in 100 mM carbonate-bicarbonate coating solution (pH 9.6), washed with PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (PBST), and blocked with PBST-1%BSA. After washing in PBST, 25 μL of blocking solution or three-fold serial dilutions of mouse sera samples in blocking solution were applied and incubated overnight at 4°C. Wells were washed with PBST and incubated with 1:4000 HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgA (Life Technologies), 1:2000 biotinylated rat monoclonal LO-ME-3 anti-mouse IgE epsilon chain (AbCam, Cambridge, MA), 1:2000 HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (γ1) (Molecular Probes), 1:2000 HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2a (γ) (Life Technologies), 1:2000 HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2b (γ) (Life Technologies), 1:2000 HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG3 (Life Technologies), or 1:4000 HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM (Life Technologies) for 1 hr at room temperature. Biotinylated IgE incubation was followed by PBST wash and incubation in Streptavidin Poly-HRP 40 conjugate (Fitzgerald, Acton, MA) in 0.678% Universal Casein Diluent (Fitzgerald) for 30 min at room temperature. Wells were washed, developed in the dark with TMB One Component HRP Microwell substrate (Sur Modics, Eden Prairie, MN), and stopped with 0.18 M sulfuric acid. Absorbance was read at 450 nm on a VERSAmax tunable microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) with Softmax Pro 4.7.1 software. Data are expressed as titers. Antigen-specific serum antibody titers were determined as the reciprocal of the last dilution yielding absorbance values at least two-fold higher than the blank for IgE and IgGs, or at least two-fold higher than the absorbance in the non-specific antigen-coated control wells for IgA and IgM.

in vitro acquisition of OVA

Isolated total intestinal cells were cultured in 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates in complete cell culture media (RPMI 1640 with L-glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, 10% HI FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin) at a density of 300,000 cells/200 μL at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were pretreated for 20 min with PBS, 10 μg/mL LEAF-purified anti-mouse CD16/32 clone 93 (Biolegend), 10 μg/mL anti-mouse CD16 clone 275003 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), or 10 μg/mL LEAF-purified rat IgG2a κ isotype control clone RTK2758 (Biolegend). Media, serum from an OVA-sensitized mouse (1:50), or heat-inactivated OVA-sensitized serum (1:50; incubated at 56°C for 30 min) was added followed by media, 10 μg/mL non-labeled OVA, or 10 μg/mL Alexa 647 OVA. Cells were cultured for 1 hr before harvesting and staining for flow cytometry to measure OVA acquisition.

Results

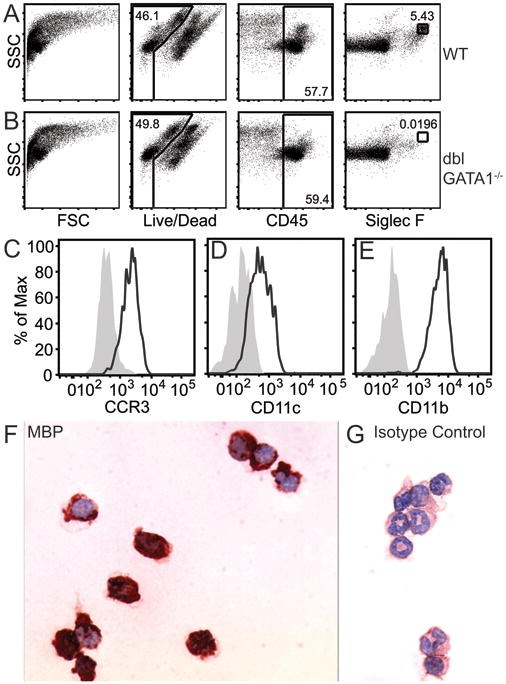

Identification and characterization of intestinal eosinophils

To study intestinal eosinophils, we isolated total cells from the small intestine of wild-type BALB/c mice using standard protocols (33) and analyzed cell surface marker expression by flow cytometry. Intestinal eosinophils were identified as a population of live, CD45+Siglec-Fhiside scatter (SSChi) cells present in the intestines of wild-type BALB/c mice (Fig. 1A) but absent in intestines isolated from eosinophil-deficient dblGATA1-/- mice (34) (Fig. 1B). Inclusion of the SSChi parameter was necessary to distinguish intestinal eosinophils from other Siglec-Fint cells (as demonstrated by comparisons with dblGATA1-/- mice and consistent with findings of Jung et al. (16)). As expected, live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi cells also expressed the chemokine receptor CCR3 (Fig. 1C), which is used in baseline recruitment of eosinophils to the intestine (35, 36). In addition, as previously reported (17, 36), intestinal eosinophils expressed the integrins and complement receptors CD11c (Fig. 1D) and CD11b (Fig. 1E). Further confirming the effectiveness of our gating strategy, sorted live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi eosinophils were greater than 98% pure (range 98.0-98.8%, n=3), as assessed by histology, i.e. granules that stained pink with eosin (data not shown), and labeling with specific antibodies against the eosinophil granule protein major basic protein 1 (MBP1) (Fig. 1F,G, a gift of Nancy and Jamie Lee).

Figure 1.

Identification and characterization of eosinophils from mouse small intestine. Live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi staining of intestinal cells from wild-type (WT) BALB/c (A) or sensitized eosinophil-deficient dblGATA1-/- BALB/c (B) mice. Expression of CCR3 (C), CD11c (D), and CD11b (E) on gated intestinal eosinophils (live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi cells) relative to matched isotype controls (filled gray). Sorted eosinophils from OVA-sensitized WT mice were stained with anti-MBP1 (dark red) (F) or matched isotype control (G). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Intestinal eosinophils acquire luminal antigen in sensitized mice

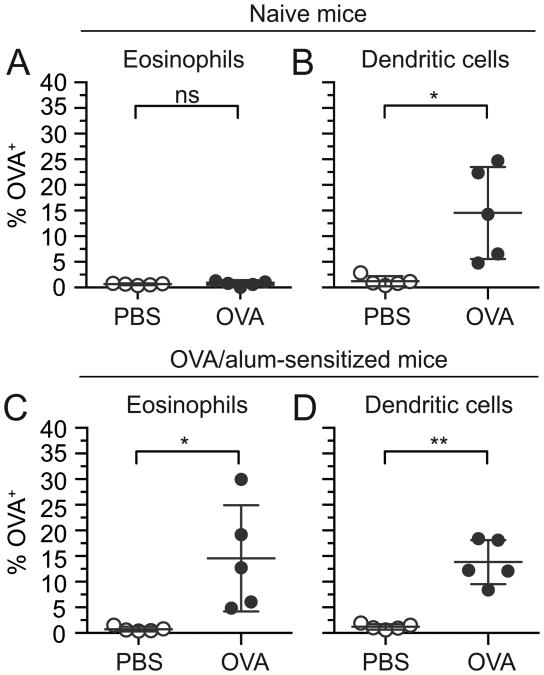

Having identified and characterized eosinophils from the mouse small intestine, we used a mouse ligated intestinal loop model to determine whether eosinophils acquire fluorescently labeled antigens from the intestinal lumen in vivo. Ligated intestinal loop surgeries were used to bypass the stomach and thereby maximize the concentration of fluorescently conjugated antigen available within the lumen for uptake and detection, enabling investigations of antigen acquisition in vivo in live mice. Forty-five minutes after introduction of fluorescently labeled OVA into the lumen of anesthetized mice, intestinal loops were excised and leukocytes isolated and analyzed for expression of the fluorescent OVA. The percentages of antigen-positive eosinophils (live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi) and dendritic cells (defined as live, CD45+CD11c+ cells after exclusion of Siglec-FhiSSChi eosinophils) were determined by comparing fluorescence in cells isolated from mice treated with fluorescently labeled antigen to autofluorescence in cells isolated from mice treated with either control vehicle (PBS) or non-labeled antigen (see Supplemental Fig. 1 for gating). Eosinophils isolated from intestinal loops of naive wild-type mice injected with fluorescently labeled OVA (Alexa 488 or 647) had not acquired OVA (Fig. 2A). In contrast, as expected a subset of dendritic cells acquired OVA under these conditions (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Intestinal eosinophils acquire lumen-derived antigen in OVA-sensitized, but not naïve mice. Two suture-ligated loops were created proximal to the cecum and injected with PBS (vehicle control) or fluorescently labeled OVA. Intestinal loops were harvested after 45 min, and total intestinal cells were isolated and stained for analysis of antigen acquisition by flow cytometry. The percentage of OVA+ eosinophils (live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi) (A,C) and OVA+ dendritic cells (remaining live, CD45+CD11c+ cells after omission of eosinophils) (B,D) were measured in naïve mice (A,B) and OVA-sensitized mice (C,D). Data are mean ± SD of 5 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed student t-test with Welch's correction for unequal variances. ns=not significant, *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01

In general, antigens encountered for the first time through the gastrointestinal mucosa induce antigenic tolerance. To determine whether a break in tolerance would affect the capacity of eosinophils to access luminal antigen, we next asked whether intestinal eosinophils might acquire antigen in parenterally sensitized mice. Mice were systemically sensitized i.p. with OVA in the presence of alum adjuvant on days 0, 7, and 14. This was followed by a challenge administration of fluorescently labeled OVA or PBS delivered into intestinal loops on day 21. As anticipated and similar to naïve mice, intestinal dendritic cells in OVA-sensitized mice acquired lumen-derived antigen (Fig. 2D). In contrast to naive mice, eosinophils isolated from intestinal loops of OVA-sensitized mice also acquired OVA from the intestinal lumen (Fig. 2C). Lumen-derived antigen was acquired by eosinophils isolated with both lamina propria (LP) and intraepithelial (IE) cell preparations (Supplemental Fig. 2). OVA acquisition by both eosinophils and dendritic cells also occurred in OVA-sensitized mice on the C57BL/6 background (Supplemental Fig. 3).

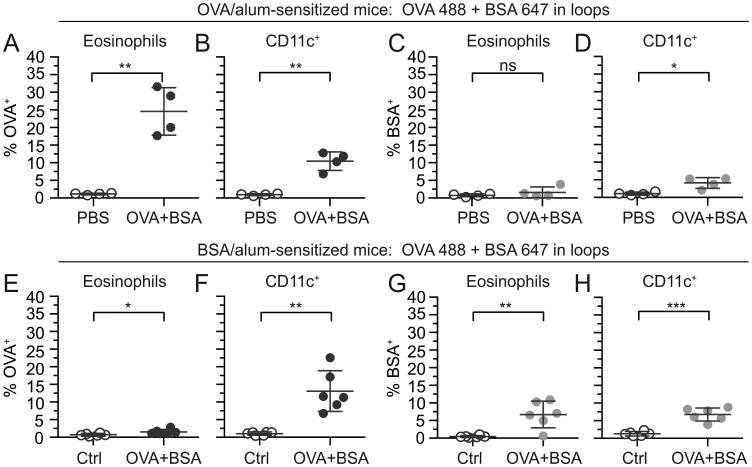

Antigen acquisition by intestinal eosinophils is restricted to the sensitizing antigen

We next asked whether antigen acquisition by eosinophils is antigen-specific or if intestinal antigen challenge permitted a generalized uptake of bystander antigens, through barrier breach or other mechanisms. Therefore, to distinguish between an antigen non-specific barrier breach effect or antigen-specific acquisition by eosinophils, mice were sensitized with OVA/alum and challenged with a combination of Alexa 488-labeled OVA and Alexa 647-labeled BSA in intestinal loops (Fig. 3A-D). As anticipated, both eosinophils and dendritic cells from OVA-sensitized mice acquired lumen-delivered OVA (Fig. 3A,B). However, only dendritic cells (Fig. 3D) and not eosinophils (Fig. 3C) were able to acquire lumen-delivered BSA. The reverse experiment was also carried out, where mice were sensitized with BSA/alum followed by challenge with combined OVA 488 and BSA 647 in intestinal loops (Fig. 3E-H). Dendritic cells acquired both OVA (Fig. 3F) and BSA (Fig. 3H) from the lumen of BSA-sensitized mice, while eosinophils only acquired BSA (not OVA) in appreciable quantities from the intestinal lumen (Fig. 3E,G).

Figure 3.

Antigen acquisition by intestinal eosinophils in sensitized mice is specific to the sensitization antigen. Vehicle control (PBS), combined non-labeled OVA and BSA (Ctrl), or combined OVA 488 and BSA 647 were injected into intestinal loops in OVA-sensitized mice (A-D) or BSA-sensitized mice (E-H). Intestinal loops were harvested after 45 min, and total intestinal cells were isolated and stained for analysis of antigen acquisition by flow cytometry. The percentage of OVA+ (A,E) and BSA+ (C,G) eosinophils (live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi) and OVA+ (B,F) and BSA+ (D,H) CD11c+ cells (live, CD45+CD11c+, no eosinophil exclusion) were measured. Data are mean ± SD of 4-6 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed student t-test with Welch's correction for unequal variances. ns=not significant, *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001.

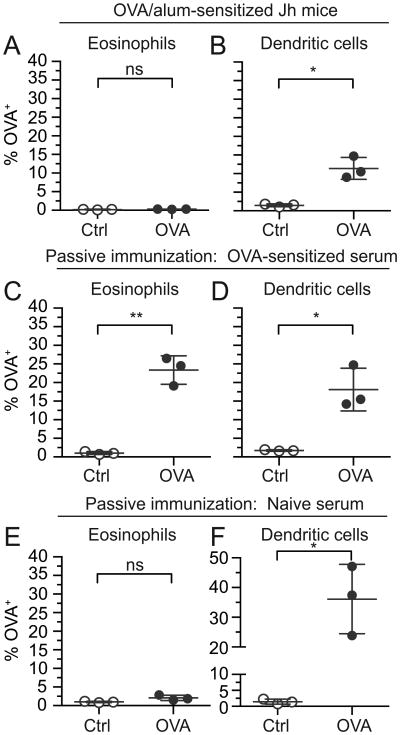

Antigen acquisition by intestinal eosinophils is immunoglobulin-dependent

Since antigen acquisition by intestinal eosinophils was specific to the sensitization antigen, we asked whether immunoglobulins are required for eosinophils to acquire antigen from the intestinal lumen. To test this, we used Jh mice, which carry a J segment deletion in the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus and consequently do not produce mature B cells, and therefore do not express detectable serum immunoglobulins (37). Jh mice were sensitized with OVA/alum and challenged with OVA 647 in intestinal loops. Similar to wild-type mice (Fig. 2D), dendritic cells were competent to acquire OVA from intestinal lumens of sensitized Jh mice (Fig. 4B). In contrast, unlike wild-type mice (Fig. 2C) prior OVA sensitization failed to enable intestinal eosinophils to acquire OVA from the intestinal lumen of Jh mice (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Intestinal eosinophils acquire antigen via an immunoglobulin-dependent mechanism. OVA 647 or control non-labeled OVA (Ctrl) was injected into intestinal loops in OVA-sensitized Jh mice that lack serum immunoglobulins (A,B), naive mice passively immunized with immune serum from OVA-sensitized mice 24 h prior (C,D), or naive mice passively immunized with non-immune serum from naive mice 24 h prior (E,F). Intestinal loops were harvested after 45 min, and total intestinal cells were isolated and stained for analysis of antigen acquisition by flow cytometry. The percentage of OVA+ eosinophils (live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi)(A,C,E) and OVA+ dendritic cells (remaining live, CD45+CD11c+ cells after omission of eosinophils)(B,D,F) were measured. Data are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed student t-test with Welch's correction for unequal variances. ns=not significant, *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01

Jh mice also exhibit impaired M cell and Peyer's patch development (38), which could influence eosinophil access to antigen, independent of immunoglobulins. Therefore, we confirmed the sufficiency of antigen-specific immunoglobulins for antigen acquisition by eosinophils by passively immunizing otherwise naïve wild-type mice with serum collected from OVA-sensitized mice 24 h prior to injection of OVA 647 into intestinal loops. Passive transfer of immune serum was sufficient to enable resident intestinal eosinophils from otherwise naïve mice to access lumen-derived OVA (Fig. 4C). As a negative control, passive immunization with naïve serum failed to promote antigen acquisition by intestinal eosinophils (Fig. 4E). Consistent with immunoglobulins not being required for OVA uptake by dendritic cells, dendritic cells acquired OVA in mice passively immunized with either OVA-sensitized serum (Fig. 4D) or control naïve serum (Fig. 4F).

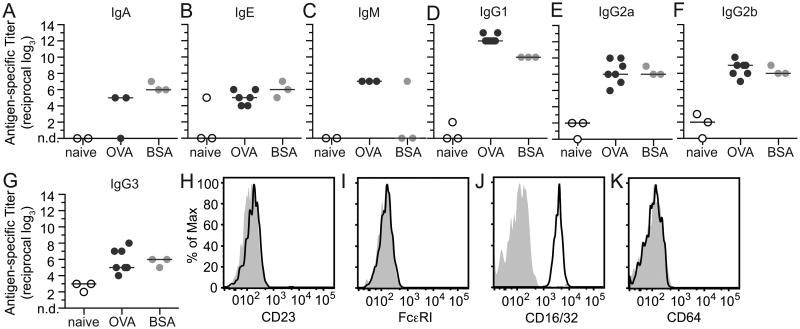

IgE is not required for eosinophil acquisition of luminal antigen

Experiments with Jh mice and passive immunization both supported a role for immunoglobulins in eosinophil acquisition of antigen from the lumen (Fig. 4). To further determine the relevant immunoglobulin isotype(s), we measured antigen-specific sera titers in naïve, OVA-sensitized, and BSA-sensitized mice by ELISA. Antigen-specific immunoglobulins were detected for IgA, IgE, IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 (Fig. 5A-G), with the highest titer measured for antigen-specific IgG1 (Fig. 5D). Because of their established associations with allergic diseases, we queried specific roles for IgE and IgG.

Figure 5.

Antigen-specific immunoglobulins are produced following sensitization and intestinal eosinophils express low affinity Fc receptors for IgG. Antigen-specific immunoglobulin titers were measured by ELISA in serum from naïve mice (white, A-H) and following i.p. sensitization with either OVA/alum (dark gray, A-H) or BSA/alum (light gray, A-H) for IgA (A), IgE (B), IgM (C), IgG1 (D), IgG2a (E), IgG2b (F), and IgG3 (G). Intestinal cells were isolated from naïve mice and expression of low affinity IgE receptors CD23 (H), high affinity IgE receptors FcεRI (I), low affinity IgG receptors CD16/32 (J)(antibody recognizes both), and high affinity IgG receptors CD64 (K) were measured in eosinophils (live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi) relative to matched isotype controls (filled gray histograms) by flow cytometry. Individual and median titers are shown in A-G, and data in H-K are representative of 3-4 independent experiments. nd=not detected

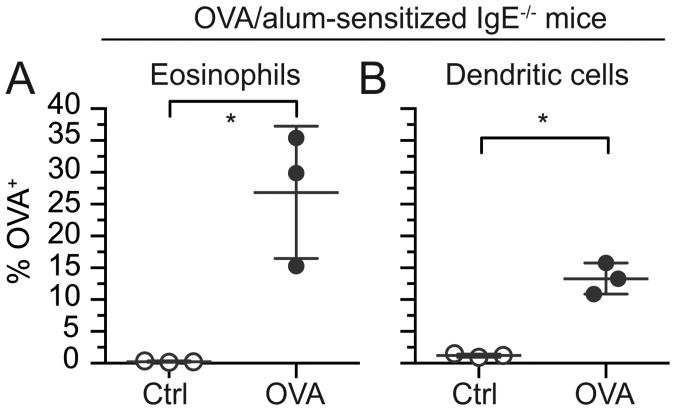

Since the expression of Fc receptors for IgE and IgG by tissue eosinophils was unknown, and tissue eosinophils have been demonstrated to express distinct patterns of cell surface proteins (36), we assessed their expression on intestinal eosinophils. By flow cytometry eosinophils isolated from the small intestine of naïve wild-type mice expressed neither high- nor low-affinity Fc receptors for IgE (Fig. 5H,I and Supplemental Fig. 4 for positive control staining) suggesting resident tissue eosinophils in mice do not engage IgE directly. To investigate an indirect effect of IgE, intestinal loop ligations were performed using OVA-sensitized IgE deficient mice. Similar to OVA-sensitized wild-type mice (Fig. 2C,D), both eosinophils and dendritic cells from sensitized IgE-deficient mice were able to acquire OVA from the intestinal lumen (Fig. 6A,B). Taken together, these data suggest antigen-specific IgE is not necessary for eosinophils to acquire luminal antigen.

Figure 6.

IgE is not required for eosinophil acquisition of luminal antigen. OVA 647 or control non-labeled OVA (Ctrl) was injected into intestinal loops in IgE-deficient OVA-sensitized IgE-/- mice. Intestinal loops were harvested after 45 min, and total intestinal cells were isolated and stained for analysis of antigen acquisition by flow cytometry. The percentage of OVA+ eosinophils (live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi) (A) and OVA+ dendritic cells (remaining live, CD45+CD11c+ cells after omission of eosinophils) (B) were measured. Data are mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed student t-test with Welch's correction for unequal variances. *=p<0.05

Eosinophils acquire antigen via low affinity IgG receptors

Intestinal eosinophils from wild-type mice were further assessed for surface expression of high and low affinity IgG Fc receptors. Although high affinity IgG receptors (CD64) were not detected on intestinal eosinophils, antibodies recognizing a common motif shared by CD32 (FcγRII) and CD16 (FcγRIII) demonstrate resident intestinal eosinophils uniformly express low affinity IgG receptors (Fig. 5J,K and Supplemental Fig. 4 for positive controls).

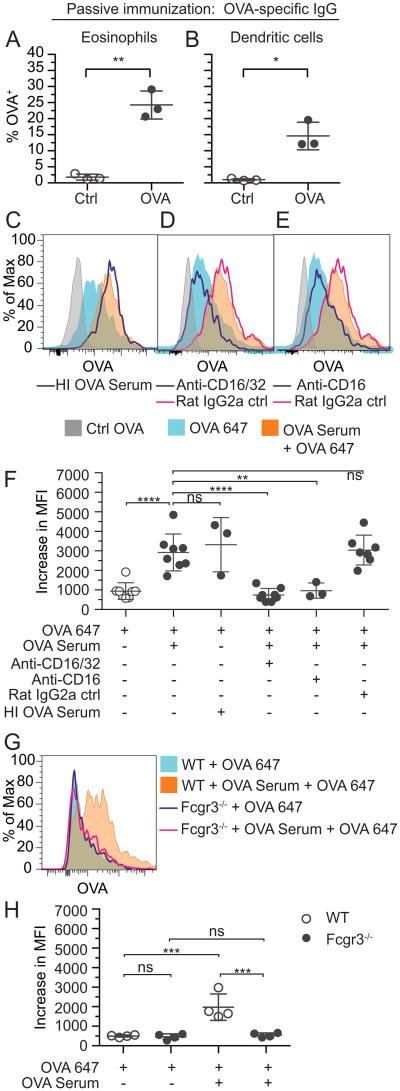

Because small intestinal eosinophils expressed low affinity Fc receptors for IgG, we asked whether passive transfer of antigen-specific IgG is sufficient to enable eosinophils to acquire luminal antigen in vivo. IgG was isolated from OVA-sensitized mouse immune serum and used to passively immunize naïve mice. Passive immunization with OVA-specific IgG was sufficient to enable intestinal eosinophils of otherwise naive mice to acquire OVA 647 from intestinal loops (Fig. 7A). As expected, dendritic cells also acquired OVA (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Intestinal eosinophils acquire antigen via IgG and the low-affinity IgG receptor FcγRIII (CD16). OVA 647 or control non-labeled OVA (Ctrl) was injected into intestinal loops in otherwise naïve mice passively immunized 24 h prior with IgG isolated from OVA-sensitized immune serum. Intestinal loops were harvested after 45 min, and total intestinal cells were isolated and stained for analysis of antigen acquisition by flow cytometry. The percentage of OVA+ eosinophils (live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi) (A) and OVA+ dendritic cells (remaining live, CD45+CD11c+ cells after omission of eosinophils) (B) were measured. (C-F) Intestinal cells isolated from naïve BALB/c mice were cultured for 1 h with control non-labeled OVA (Ctrl OVA, filled gray, C-E), OVA 647 (filled blue, C-F), OVA 647 + serum from OVA-sensitized mice (filled orange, C-F), or OVA 647 + heat inactivated (HI) serum from OVA-sensitized mice (dark blue line, C). In some cases, cells were pretreated for 20 min with a CD16/32 blocking antibody (dark blue line, D,F), a CD16 blocking antibody (dark blue line, E,F), or a rat IgG2a isotype control antibody (pink line, D,E,F). Intestinal cells isolated from naïve C57BL/6 mice (WT) or FcγRIII-deficient mice (Fcgr3-/-) were cultured for 1 h with OVA 647 (filled blue or dark blue line, G) or OVA 647 + serum from OVA-sensitized mice (filled orange or pink line, G). Cells were then washed and stained to identify eosinophils and antigen acquisition was measured by flow cytometry in eosinophils (live, CD45+Siglec-FhiSSChi) (C-H). Quantification of increases in median fluorescence intensity (MFI) relative to cells treated with non-labeled OVA (F,H). Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments in A,B and 3-8 independent experiments in F,H, of which one representative example is shown in C-E,G. Statistical significance in A,B was determined by a two-tailed student t-test with Welch's correction for unequal variances. Statistical significance in F,H was determined by an ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. ns=not significant, *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001, ****=p<0.0001

To further investigate the mechanism of eosinophil acquisition of antigen by antigen-specific IgG, we assessed the acquisition of OVA by intestinal eosinophils ex vivo. To avoid the potential functional effects of labeling eosinophils with antibodies for sorting, we cultured unsorted intestinal cells for 1 h with non-labeled control OVA, OVA 647 alone, or OVA 647 in combination with serum from OVA-sensitized mice. Following antigen acquisition, cells were stained for analysis by flow cytometry, and eosinophil acquisition of OVA 647 was measured. In vitro, in contrast to in vivo (Fig. 2A), intestinal eosinophils from naive mice readily acquired OVA, regardless of the presence of immune serum (Fig. 7C-F). Serum from OVA-sensitized mice further increased eosinophil acquisition of OVA 647 (Fig. 7C-F). Increased OVA acquisition was not mediated by complement as heat inactivated immune serum was still sufficient for increased acquisition of OVA 647 (Fig. 7C,F). Increased OVA acquisition was completely blocked by pre-treating cells with either a CD16/32 blocking antibody (Fig. 7D,F) or a blocking antibody specifically targeting CD16(39) (Fig. 7E,F) but not a rat IgG2a isotype control antibody (Fig. 7D-F), suggesting low affinity IgG receptors, specifically CD16 (FcγRIII), are required for IgG-mediated acquisition of antigen by intestinal eosinophils. To confirm immunoglobulin-mediated antigen acquisition by eosinophils does not require an accessory cell(s), in vitro culture was also performed with intestinal eosinophils isolated by cell sorting and yielded the same results (data not shown). To further test whether FcγRIII is necessary for IgG-mediated acquisition of antigen by intestinal eosinophils, we isolated intestinal cells from wild-type C57BL/6 mice or FcγRIII-deficient mice (Fcgr3-/-) and treated them for 1 h with OVA 647 or OVA 647 in combination with serum from OVA-sensitized mice (Fig 7. G,H). Similar to BALB/c mice (Fig 7. C-F), eosinophils from C57BL/6 mice acquired OVA in the absence of serum in vitro (Fig 7. H), and this acquisition was significantly increased by the addition of serum from OVA-sensitized mice (Fig 7. G,H). In contrast, eosinophils deficient for FcγRIII were unable to acquire additional OVA in the presence of immune serum (Fig 7. G,H) and pretreatment with a CD16/32 blocking antibody did not reduce OVA acquisition in these eosinophils (data not shown) suggesting that CD16 alone is necessary for IgG-mediated acquisition of antigen by intestinal eosinophils.

Discussion

Under healthy conditions eosinophils home naturally to the intestinal tract where they reside in greater densities than in other tissues, and their granule-derived products increase in several inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases including IBDs (6), food allergies (1), and EGIDs (2). However, their presence as resident immune cells has been largely overlooked, and their physiological functions in disease pathogenesis remain enigmatic. Direct engagement of antigen by eosinophils elicits downstream effector functions including activation, degranulation, release of reactive oxygen species, and antigen presentation (18-21, 25). It had been unknown whether the large population of native eosinophils resident within the small intestine and separated by an epithelial layer from oral antigens entering the lumen might encounter antigen in vivo,. Here we show that resident small intestinal eosinophils access and acquire soluble antigens derived from the intestinal lumen of antigen-sensitized (but not naïve) mice in vivo. Antigen acquisition by intestinal eosinophils is mediated through IgG-antigen immune complexes and the eosinophil-expressed low affinity activating receptor FcγRIII.

Studies with eosinophil deficient mice reveal requirements for eosinophils in normal Peyer's patch development and mucosal IgA production (15, 16), and in the absence of eosinophils oral tolerance induction was diminished (16) and the intestinal microbiota altered (15, 16). Therefore, resident intestinal eosinophils and their products participate in the regulation of intestinal homeostasis. Moreover, in a model of oral sensitization-induced peanut allergy eosinophil-deficient mice further demonstrated that intestinal eosinophils and their products are required for dendritic cell induction of primary Th2 immunity (17). Some intestinal inflammatory diseases are associated with increased eosinophils (e.g. food allergies and EGIDs) and are triggered by secondary exposure to food antigens; therefore assessing the potential for resident intestinal eosinophils to engage lumen-derived antigen, which would allow them to participate in antigen-driven effector functions in vivo is important. We used wild-type mice to directly assess whether or not tissue-resident eosinophils acquire lumen-derived antigens in primary or challenge exposures. Our findings that humoral immunity facilitates antigen engagement by FcγRIII-expressing native lamina propria eosinophils now extend the physiological functions of resident intestinal eosinophils to capturing antigen during secondary immune responses.

Our data show that small intestine eosinophils do not acquire detectable levels of lumen-derived antigen in naïve mice in vivo (Fig. 2A), although ex vivo intestinal eosinophils from naïve mice readily acquired free OVA in culture (Fig. 7C-F,H). Uptake of free OVA in vitro is likely mediated by pinocytosis as splenic murine eosinophils or human blood eosinophils will readily accumulate detectable levels of the membrane-impermeant dyes lucifer yellow or sulforhodamine within minutes (data not shown). Thus, when interpreted along with the in vitro data, our in vivo data suggest that LP eosinophils of naïve mice, although capable of pinocytosing soluble antigens, do not encounter sufficient quantities of lumen-derived antigens in naïve mice in vivo. These data highlight a clear distinction between antigen acquisition by LP eosinophils and the gut sampling roles of dendritic cells in primary immunity. These data also suggest that the reported role for eosinophil-derived granule proteins in dendritic cell activation during primary immunity (17) is independent of direct antigen engagement.

Rather, the ability of tissue eosinophils to acquire antigen in situ in this model depends upon humoral immunity (Fig. 4), i.e. antigen-specific IgG, and eosinophil-expressed FcγRIII (Fig. 7). Sufficiency of systemic antigen-specific IgG, whether generated naturally in vivo through antigen sensitization or transferred via passive immunization, to provide small intestine eosinophils access to luminal antigen (Fig. 7A) suggests antigen sensitization via any site that activates humoral immunity (e.g. epicutaneous or inhaled) will enable antigen acquisition by resident FcγRIII-expressing intestinal eosinophils upon secondary oral exposure, and implicates tissue-resident eosinophils specifically in IgG-mediated allergic disease outcomes.

Our flow cytometry data indicate that resident mouse intestinal lamina propria eosinophils do not express appreciable levels of low or high affinity Fc receptors for IgE (Fig. 5H,I), and our in vivo data in IgE-/- mice further confirm that IgE is not necessary for eosinophils to acquire luminal antigen (Fig. 6A), either directly or indirectly. Our in vitro data also imply that neither IgE nor IgA are required for eosinophils to acquire antigen, as increased OVA accumulation in the presence of OVA-sensitized immune serum (which contains antigen-specific IgA and IgE in addition to IgG (see Fig. 5A,B)) is completely ablated by neutralizing antibodies against low affinity IgG receptors (Fig. 7D-F) and does not occur in the absence of FcγRIII (Fig. 7G,H). In contrast to mouse eosinophils (reference (40) and now extended to intestinal eosinophils in Fig. 5), human eosinophils can be induced to express high affinity IgE receptors (41). Therefore, although IgE was not necessary for antigen acquisition by eosinophils in this mouse study, FcεRI crosslinking of human intestinal eosinophils might be biologically relevant. Moreover, human peripheral blood eosinophils express FcαR (CD89)(42), polymeric IgR receptor (43), transferrin receptor 1 (CD71)(43), and asialoglycoprotein receptor (43), which all bind IgA, and IgA complexes induced superoxide production and degranulation in human eosinophils in vitro (25). Therefore, although serum IgA was not sufficient to induce antigen acquisition by mouse intestinal eosinophils, further studies are needed to define the Fc receptor repertoire expressed by human intestinal tissue eosinophils to predict isotype specificities and physiological outcomes.

Since cell surface Fc receptor expression on peripheral blood eosinophils is known to change with the cytokine environment (44), it was important to determine the expression of Fcγ receptors on resident intestinal eosinophils. Similar to mouse eosinophils from peripheral blood (39), peritoneum (44), and liver granulomas, but notably not in vitro bone marrow-derived eosinophils (40), mouse intestinal eosinophils expressed low affinity (i.e. FcγRII and/or FcγRIII) but not high affinity (i.e. FcγRI) Fcγ receptors (Fig. 5J,K). Binding of IgG to low affinity Fc receptors requires crosslinking for stabilization (45), suggesting antigen acquired by intestinal eosinophils through low affinity Fcγ receptors is in the form of immune complexes. Our in vitro neutralization data and studies with FcγRIII-deficient eosinophils further specifically implicate eosinophil-expressed FcγRIII (Fig. 7).

Live imaging studies show that OVA primarily crosses the epithelium of the small intestine through GAPs and Peyer's patches (46). As we eliminated Peyer's patches from our analysis, it is unlikely that eosinophils are acquiring antigen from M cells in the follicle associated epithelium above Peyer's patches. In addition, our data do not support eosinophils extending processes into the lumen to sample antigen, since isolated intestinal eosinophils readily pinocytose antigen in vitro (Fig. 7) but do not acquire detectable levels of lumen-derived antigen in vivo in naïve mice (Fig. 1). The specificity of eosinophil antigen acquisition (Fig. 3) also implies that antigen acquisition is not simply due to increased intestinal permeability. We interpret these data to suggest antigen-specific IgG entering small intestinal tissues through the vasculature captures the low levels of lumen-derived soluble antigen that access the lamina propria through GAPs or alternative means of transcellular transport into immune complexes, which are then readily bound by eosinophil-expressed FcγRIII. Therefore, we hypothesize that IgG focuses the low levels of antigens that access lamina propria tissues onto eosinophil-expressed FcγRIII, enabling resident intestinal eosinophils to specifically engage those antigens against which humoral immunity has been generated.

Mouse FcγRIII is an activating receptor with an ITAM motif (47). Fc receptor repertoires and functions are not directly transposable between mice and humans (47); unlike mouse eosinophils, human peripheral blood eosinophils constitutively express FcγRIIA (21, 48), which, like mouse FcγRIII, is an activating receptor (47). A number of in vitro studies using eosinophils from rodents and human blood demonstrate that exposure of eosinophils to immune complexes or cross-linking eosinophil-expressed Fc gamma receptors elicits eosinophil activation (22), degranulation of cationic granule proteins (21, 25, 49), growth factor (23) and cytokine secretion (50, 51), superoxide production (25), enhanced survival (24), and antigen presenting cell functions to expand both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes (51). Our data shown here now provide a mechanism by which these known Fc gamma receptor-dependent functions may be linked to resident intestinal eosinophils in vivo in secondary immunity. Specific outcomes of FcγRIII engagement are likely context-dependent in vivo. Therefore, further studies are needed to delineate the physiological outcomes of in vivo eosinophil engagement of immune-complexed antigen within the context of inflammatory and infectious gastrointestinal diseases.

In summary, we have shown that intestinal tissue eosinophils access soluble lumen-derived antigen in vivo. Humoral immunity provides resident intestinal eosinophils with a mechanism to acquire luminal antigen through antigen-IgG immune complex formation and antigen focusing by eosinophil-expressed low affinity FcγIII receptors. These data suggest that eosinophils may engage in antigen-specific IgG-mediated immunoregulatory functions upon secondary exposure to food allergens in the intestine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants RO1HL095699 and 3P30DK034854, American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED) Hope Pilot Grant, and Harvard University's William F. Milton Fund to LAS.

Abbreviations used in this article

- EGID

eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder

- GAPs

goblet cell-associated antigen passages

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IE

intraepithelial

- LP

lamina propria

Footnotes

Disclosures The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Schwab D, Müller S, Aigner T, Neureiter D, Kirchner T, Hahn EG, Raithel M. Functional and morphologic characterization of eosinophils in the lower intestinal mucosa of patients with food allergy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1525–1534. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masterson JC, Furuta GT, Lee JJ. Update on clinical and immunological features of eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2011;27:515–522. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32834b314c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff SC, Wedemeyer J, Herrmann A, Meier PN, Trautwein C, Cetin Y, Maschek H, Stolte M, Gebel M, Manns MP. Quantitative assessment of intestinal eosinophils and mast cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Histopathology. 1996;28:1–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.262309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lampinen M, Backman M, Winqvist O, Rorsman F, Ronnblom A, Sangfelt P, Carlson M. Different regulation of eosinophil activity in Crohn's disease compared with ulcerative colitis. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2008;84:1392–1399. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0807513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bischoff SC, Mayer J, Wedemeyer J, Meier PN, Zeck-Kapp G, Wedi B, Kapp A, Cetin Y, Gebel M, Manns MP. Colonoscopic allergen provocation (COLAP): a new diagnostic approach for gastrointestinal food allergy. Gut. 1997;40:745–753. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.6.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saitoh O, Kojima K, Sugi K, Matsuse R, Uchida K, Tabata K, Nakagawa K, Kayazawa M, Hirata I, Katsu K. Fecal eosinophil granule-derived proteins reflect disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3513–3520. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobsen EA, Ochkur SI, Pero RS, Taranova AG, Protheroe CA, Colbert DC, Lee NA, Lee JJ. Allergic pulmonary inflammation in mice is dependent on eosinophil-induced recruitment of effector T cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205:699–710. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobsen EA, Zellner KR, Colbert D, Lee NA, Lee JJ. Eosinophils Regulate Dendritic Cells and Th2 Pulmonary Immune Responses following Allergen Provocation. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;187:6059–6068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Voehringer D, Shinkai K, Locksley RM. Type 2 immunity reflects orchestrated recruitment of cells committed to IL-4 production. Immunity. 2004;20:267–277. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humbles AA, Lloyd CM, McMillan SJ, Friend DS, Xanthou G, McKenna EE, Ghiran S, Gerard NP, Yu C, Orkin SH, Gerard C. A critical role for eosinophils in allergic airways remodeling. Science. 2004;305:1776–1779. doi: 10.1126/science.1100283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu D, Molofsky AB, Liang HE, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Jouihan HA, Bando JK, Chawla A, Locksley RM. Eosinophils sustain adipose alternatively activated macrophages associated with glucose homeostasis. Science. 2011;332:243–247. doi: 10.1126/science.1201475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heredia JE, Mukundan L, Chen FM, Mueller AA, Deo RC, Locksley RM, Rando TA, Chawla A. Type 2 innate signals stimulate fibro/adipogenic progenitors to facilitate muscle regeneration. Cell. 2013;153:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu VT, Fröhlich A, Steinhauser G, Scheel T, Roch T, Fillatreau S, Lee JJ, Löhning M, Berek C. Eosinophils are required for the maintenance of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Nature Publishing Group. 2011;12:151–159. doi: 10.1038/ni.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu VT, Berek C. Immunization induces activation of bone marrow eosinophils required for plasma cell survival. Eur J Immunol. 2011;42:130–137. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu VT, Beller A, Rausch S, Strandmark J, Zänker M, Arbach O, Kruglov A, Berek C. Eosinophils Promote Generation and Maintenance of Immunoglobulin-A-Expressing Plasma Cells and Contribute to Gut Immune Homeostasis. Immunity. 2014;40:582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung Y, Wen T, Mingler MK, Caldwell JM, Wang YH, Chaplin DD, Lee EH, Jang MH, Woo SY, Seoh JY, Miyasaka M, Rothenberg ME. IL-1β in eosinophil-mediated small intestinal homeostasis and IgA production. Mucosal Immunology. 2015;8:930–942. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu DK, Jimenez-Saiz R, Verschoor CP, Walker TD, Goncharova S, Llop-Guevara A, Shen P, Gordon ME, Barra NG, Bassett JD, Kong J, Fattouh R, McCoy KD, Bowdish DM, Erjefält JS, Pabst O, Humbles AA, Kolbeck R, Waserman S, Jordana M. Indigenous enteric eosinophils control DCs to initiate a primary Th2 immune response in vivo. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2014;211:1657–1672. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKenzie JR, Mattes J, Dent LA, Foster PS. Eosinophils promote allergic disease of the lung by regulating CD4(+) Th2 lymphocyte function. J Immunol. 2001;167:3146–3155. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi HZ, Humbles A, Gerard C, Jin Z, Weller PF. Lymph node trafficking and antigen presentation by endobronchial eosinophils. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:945–953. doi: 10.1172/JCI8945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang HB, Ghiran I, Matthaei K, Weller PF. Airway eosinophils: allergic inflammation recruited professional antigen-presenting cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:7585–7592. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneko M, Swanson MC, Gleich GJ, Kita H. Allergen-specific IgG1 and IgG3 through Fc gamma RII induce eosinophil degranulation. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2813–2821. doi: 10.1172/JCI117986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lach-Trifilieff E, Menear K, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz VLJ, Walker C. Syk-deficient eosinophils show normal interleukin-5–mediated differentiation, maturation, and survival but no longer respond to FcγR activation. Blood. 2000;96:2506–2510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi H, Gleich GJ, Butterfield JH, Kita H. Human eosinophils produce neurotrophins and secrete nerve growth factor on immunologic stimuli. Blood. 2002;99:2214–2220. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JT, Schimming AW, Kita H. Ligation of FcγRII (CD32) Pivotally Regulates Survival of Human Eosinophils. J Immunol. 1999;162:4253–4259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muraki M, Gleich GJ, Kita H. Antigen-specific IgG and IgA, but not IgE, activate the effector functions of eosinophils in the presence of antigen. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;154:119–127. doi: 10.1159/000320226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulz O, Pabst O. Antigen sampling in the small intestine. Trends in Immunology. 2012:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDole JR, Wheeler LW, McDonald KG, Wang B, Konjufca V, Knoop KA, Newberry RD, Miller MJ. Goblet cells deliver luminal antigen to CD103+ dendritic cells in the small intestine. Nature. 2012;483:345–349. doi: 10.1038/nature10863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chieppa M, Rescigno M, Huang AYC, Germain RN. Dynamic imaging of dendritic cell extension into the small bowel lumen in response to epithelial cell TLR engagement. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2841–2852. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, Francolini M, Rotta G, Bonasio R, Granucci F, Kraehenbuhl JP, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:361–367. doi: 10.1038/86373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshida M, Claypool SM, Wagner JS, Mizoguchi E, Mizoguchi A, Roopenian DC, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS. Human Neonatal Fc Receptor Mediates Transport of IgG into Luminal Secretions for Delivery of Antigens to Mucosal Dendritic Cells. Immunity. 2004;20:769–783. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roopenian DC, Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knoop KA, Kumar N, Butler BR, Sakthivel SK, Taylor RT, Nochi T, Akiba H, Yagita H, Kiyono H, Williams IR. RANKL is necessary and sufficient to initiate development of antigen-sampling M cells in the intestinal epithelium. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;183:5738–5747. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheridan BS, Lefrançois L. Isolation of mouse lymphocytes from small intestine tissues. In: Coligan JE, Bierer BE, Margulies DH, shevach EM, Strober W, Brown P, Conovan JC, editors. Current protocols in immunology. Supplement 99. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2012. pp. 3.19.1–3.19.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu C, Cantor AB, Yang H, Browne C, Wells RA, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH. Targeted deletion of a high-affinity GATA-binding site in the GATA-1 promoter leads to selective loss of the eosinophil lineage in vivo. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1387–1395. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishra A, Hogan SP, Lee JJ, Foster PS, Rothenberg ME. Fundamental signals that regulate eosinophil homing to the gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1719–1727. doi: 10.1172/JCI6560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carlens J, Wahl B, Ballmaier M, Bulfone-Paus S, Förster R, Pabst O. Common gamma-chain-dependent signals confer selective survival of eosinophils in the murine small intestine. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;183:5600–5607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, Trounstine M, Alt FW, Young F, Kurahara C, Loring JF, Huszar D. Immunoglobulin gene rearrangement in B cell deficient mice generated by targeted deletion of the JH locus. Int Immunol. 1993;5:647–656. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golovkina TV, Shlomchik M, Hannum L, Chervonsky A. Organogenic role of B lymphocytes in mucosal immunity. Science. 1999;286:1965–1968. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jönsson F, Mancardi DA, Kita Y, Karasuyama H, Iannascoli B, Van Rooijen N, Shimizu T, Daëron M, Bruhns P. Mouse and human neutrophils induce anaphylaxis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1484–1496. doi: 10.1172/JCI45232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Andres B, Rakasz E, Hagen M, McCormik ML, Mueller AL, Elliot D, Metwali A, Sandor M, Britigan BE, Weinstock JV, Lynch RG. Lack of Fc-epsilon receptors on murine eosinophils: implications for the functional significance of elevated IgE and eosinophils in parasitic infections. Blood. 1997;89:3826–3836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kayaba H, Dombrowicz D, Woerly G, Papin JP, Loiseau S, Capron M. Human eosinophils and human high affinity IgE receptor transgenic mouse eosinophils express low levels of high affinity IgE receptor, but release IL-10 upon receptor activation. J Immunol. 2001;167:995–1003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monteiro RC, Hostoffer RW, Cooper MD, Bonner JR, Gartland GL, Kubagawa H. Definition of immunoglobulin A receptors on eosinophils and their enhanced expression in allergic individuals. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1681–1685. doi: 10.1172/JCI116754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Decot V, Woerly G, Loyens M, Loiseau S, Quatannens B, Capron M, Dombrowicz D. Heterogeneity of expression of IgA receptors by human, mouse, and rat eosinophils. J Immunol. 2005;174:628–635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Andres B, Cárdaba B, del Pozo V, Martín-Orozco E, Gallardo S, Tramón P, Palomino P, Lahoz C. Modulation of the Fc gamma RII and Fc gamma RIII induced by GM-CSF, IFN-gamma and IL-4 on murine eosinophils. Immunology. 1994;83:155–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcγ receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howe SE, Lickteig DJ, Plunkett KN, Ryerse JS, Konjufca V. The uptake of soluble and particulate antigens by epithelial cells in the mouse small intestine. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruhns P. Properties of mouse and human IgG receptors and their contribution to disease models. Blood. 2012;119:5640–5649. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-380121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Looney RJ, Ryan DH, Takahashi K, Fleit HB, Cohen HJ, Abraham GN, Anderson CL. Identification of a second class of IgG Fc receptors on human neutrophils. A 40 kilodalton molecule also found on eosinophils. J Exp Med. 1986;163:826–836. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.4.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davoine F, Labonté I, Ferland C, Mazer B, Chakir J, Laviolette M. Role and modulation of CD16 expression on eosinophils by cytokines and immune complexes. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;134:165–172. doi: 10.1159/000078650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakajima H, Gleich GJ, Kita H. Constitutive production of IL-4 and IL-10 and stimulated production of IL-8 by normal peripheral blood eosinophils. J Immunol. 1996;156:4859–4866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garro AP, Chiapello LS, Baronetti JL, Masih DT. Rat eosinophils stimulate the expansion of Cryptococcus neoformans-specific CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells with a T-helper 1 profile. Immunology. 2011;132:174–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.