Abstract

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a drug-induced movement disorder that arises with antipsychotics. These drugs are the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and are also prescribed for major depression, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity, obsessive compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorder. There is thus a need for therapies to reduce TD. The present studies and our previous work show that nicotine administration decreases haloperidol-induced vacuous chewing movements (VCMs) in rodent TD models, suggesting a role for the nicotinic cholinergic system. Extensive studies also show that D2 dopamine receptors are critical to TD. However, the precise involvement of striatal cholinergic interneurons and D2 medium spiny neurons (MSNs) in TD is uncertain. To elucidate their role, we used optogenetics with a focus on the striatum because of its close links to TD. Optical stimulation of striatal cholinergic interneurons using cholineacetyltransferase (ChAT)-Cre mice expressing channelrhodopsin2-eYFP decreased haloperidol-induced VCMs (~50%), with no effect in control-eYFP mice. Activation of striatal D2 MSNs using Adora2a-Cre mice expressing channelrhodopsin2-eYFP also diminished antipsychotic-induced VCMs, with no change in control-eYFP mice. In both ChAT-Cre and Adora2a-Cre mice, stimulation or mecamylamine alone similarly decreased VCMs with no further decline with combined treatment, suggesting nAChRs are involved. Striatal D2 MSN activation in haloperidol-treated Adora2a-Cre mice increased c-Fos+ D2 MSNs and decreased c-Fos+ non-D2 MSNs, suggesting a role for c-Fos. These studies provide the first evidence that optogenetic stimulation of striatal cholinergic interneurons and GABAergic MSNs modulates VCMs, and thus possibly TD. Moreover, they suggest nicotinic receptor drugs may reduce antipsychotic-induced TD.

Keywords: Cholinergic interneurons, D2 Receptor-expressing neurons, GABAergic medium spiny neurons, striatum, tardive dyskinesia

Introduction

Antipsychotics are a very important class of drugs approved for the management of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and used off-label for depression, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (Canitano and Scandurra, 2011; Pickar et al., 2008; Seeman, 2010; Tarsy et al., 2011). These dopamine receptor antagonists are thought to exert their therapeutic effect by dampening dopaminergic activity (Seeman, 2010; Tarsy et al., 2011; Turrone et al., 2003). However, their continued use also results in motor side effects including tardive dyskinesia (TD) that afflicts up to 25% of treated patients (Saha et al., 2005).

TD are drug-induced repetitive abnormal involuntary movements primarily of the face and limbs that range from troubling to debilitating (Correll et al., 2004; Tarsy et al., 2011). The more recently developed second-generation antipsychotics produce less TD; however, it still arises (Correll and Schenk, 2008; Peluso et al., 2012; Tarsy et al., 2011; Woods et al., 2010). Little treatment is currently available for TD other than antipsychotic dose modification. There is thus a need for novel approaches to attenuate its occurrence. Our previous work had shown that nicotine treatment reduced haloperidol-induced abnormal movements or vacuous chewing movements (VCMs) in a rat model of TD, with a maximal reduction of 50% (Bordia et al., 2012). These findings suggest that drugs modulating the nicotinic cholinergic system may minimize TD in patients requiring antipsychotics.

The neuronal cell subtypes that contribute to TD are currently uncertain because CNS circuitry is complex and tightly integrated with numerous other neuronal systems. The striatum may be involved since it is a key region in the control of normal movement (Gittis and Kreitzer, 2012; Teo et al., 2012) and aberrant motor behaviors that arise with antipsychotics (Loonen and Ivanova, 2013). Neurotransmitter systems in the striatum that may play a role include the cholinergic one (Deffains and Bergman, 2015; Kelley and Roberts, 2004; Lovinger, 2010). Cholinergic interneurons have extensive, dense axonal arbors that are very widespread throughout the striatum despite the fact that they comprise only 2–3% of the total number of striatal neurons. Moreover, striatal cholinergic interneurons are associated with motor control and cholinergic agonists such as nicotine and varenicline decrease haloperidol-induced VCMs (Bordia et al., 2013; Quik et al., 2014). Indirect pathway GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs) are likely also involved as they express D2 receptors, and antipsychotics are thought to act by blocking D2 receptors, possibly via a compensatory receptor up-regulation in response to chronic antipsychotic treatment (Seeman, 2010; Turrone et al., 2003).

The objective of the present studies was to elucidate the role of striatal cholinergic interneurons and D2 MSNs in TD using optogenetics. This approach offers the advantage that it permits in vivo cell type specific targeting of select neuronal populations in real time. To investigate the role of the striatal cholinergic system, we used cholineacetyl transferase (ChAT)-Cre mice that allows for the selective expression and activation of channelrhodopsin2 (ChR2) in striatal cholinergic interneurons. To elucidate the involvement of striatal D2 receptor-expressing GABAergic MSNs (D2 MSNs), we used ChR2-expressing Adora2a-Cre mice in which D2 MSNs can be selectively activated. The data indicate that both cholinergic interneurons and D2 MSNs regulate TD.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All procedures conformed to the guidelines mandated by the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the SRI Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Studies with control mice

Fifty adult (18–20g) male C57 BL/6 mice (Charles River, Livermore, CA) were housed 3–4 per cage and quarantined for 2 d under a 12/12 hr light-dark cycle in a temperature and humidity-controlled room with free access to food and water. Several days later, all mice were acclimated to 2% saccharin in drinking water. They were then randomly assigned to saccharin with (n = 25) or without (n = 25) nicotine (free base; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), with saccharin used to mask the bitter taste of nicotine. Nicotine was started at 25 µg/ml and incrementally increased (50, 100, 200 µg/ml) over 10 d to a final concentration of 300 µg/ml, a dose that yields plasma cotinine levels of 200–250 ng/ml (Huang et al., 2011; Quik et al., 2012). The mice were weighed once weekly, with no significant difference between nicotine and saccharin-treated groups.

After 2 wk of saccharin/nicotine treatment, one set of mice was injected with vehicle or haloperidol (1 mg/kg intraperitoneally; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) twice daily (5 d per wk). Another set of mice was surgically implanted with blank pellets or pellets releasing 3 mg/kg/d haloperidol (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL, USA) over 90 d, after which they were replaced if necessary. The pellets were inserted under isoflurane anesthesia into the subcutaneous space on the dorsal surface (Crowley et al., 2012). Mouse weights were similar between treatments.

To rate VCMs, each mouse was placed in a circular Plexiglas chamber devoid of bedding. For the injection group, mice were allowed to acclimate in the cylinder for 2 min, injected with haloperidol and immediately rated for the number of VCMs in a 5 min period by a blinded rater. VCMs consisted of subtle chewing movements, high frequency jaw/mouth tremors and purposeless mouth openings in the vertical plane with or without tongue protrusion (Blanchet et al., 2012; Bordia et al., 2012; Turrone et al., 2002). For the pellet-treated group, mice were allowed to adapt to the cylinder for 2 min and rated. VCMs were assessed from the start of the study but only developed by 7 wk of haloperidol treatment, with the data provided for 7 wk and onwards.

Studies with genetically modified mice

Homozygous male ChAT-internal ribosome entry site-cre knockin mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (B6.129S6-Chattm1(cre)Lowl). Heterozygous male Adora2a-Cre indirect pathway (striatopallidal, D2) specific BAC transgenic mice (KG139Gsat/Mmcd, B6.FVB(Cg) background) were obtained from MMRC and bred in-house.

After acclimation, mice were bilaterally injected with cre-inducible recombinant AAV vector expressing ChR2 (AAV5.EF1a.DIO.hChR2(H134R)-eYFP.WPRE.hGH) or control vector (AAV5.EF1a.DIO.eYFP.WPRE.hGH) (Freeze et al., 2013; Threlfell et al., 2012). Virus (1 µl at 1–4 ×1012 particles/ml), obtained from the Vector Core, Univ Pennsylvania, was injected bilaterally into the striatum at: AP +0.8 mm, ML ±2.2 mm, DV −2.7 mm. Immediately after injection, the mice were implanted bilaterally with optical fibers (0.2 mm diameter) in the dorsolateral striatum (AP +0.8 mm, ML ±2.2 mm, DV −2.5 mm). Four wk after virus injection, the mice were implanted with pellets releasing haloperidol (3 mg/kg/d).

Eight wk after pellet implantation, the effect of optical illumination was determined, as described (Bordia et al., 2016). ChR2 was activated using a 473 nm diode laser adjusted such that the power was 1 mW at each fiber tip. Light intensity at 0.2 mm from the tip was calculated to be 15.9 mW/mm2 (corresponding to 73.2 mW/mm2 at the fiber tip) (http://web.stanford.edu/group/dlab/cgi-bin/graph/chart.php). Optical stimulation consisted of a single pulse (2 ms to 1 s in duration) or of various burst paradigms, as described (Cachope et al., 2012; Freeze et al., 2013; Threlfell et al., 2012), with a 0.5 s off stimulation period between pulses or bursts. Stimulation was for 5 min, during which time VCMs were scored. In some studies, the general nicotinic antagonist mecamylamine (1 mg/kg subcutaneously; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) was administered. For these experiments, each mouse was first rated without stimulation for 5 min. Mecamylamine was then injected and 30 min later the mouse was again optically stimulated and rated. The effect of mecamylamine was evaluated 30 min after injection consistent with previous work (Bordia et al., 2010; Bordia et al., 2016; Dekundy et al., 2007).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation and immunohistochemistry done as described (Bordia et al., 2016). The brains were quickly removed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2–3 day and cryopreserved in 10–30% sucrose for 3 days. They were sectioned (30 µm) using a cryostat (Leica). Every sixth section throughout the striatum (A1.4 to A-0.4) (total ~12 sections/mouse) was stained for ChAT, DARPP-32 or c-Fos. Free floating sections were rinsed, blocked and then incubated overnight at 4°C with goat anti-ChAT (1:200 dilution; Millipore), rabbit anti-DARPP-32 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) or rabbit anti-c-Fos (1:600 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology). They were next incubated for 2 h at room temperature with secondary antibody (donkey anti-goat Alexa-568; dilution 1:200; Invitrogen: or goat anti-rabbit Alexa-555; dilution 1:500; Cell Signaling Technology). Sections were rinsed, mounted onto slides using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Labs), coverslipped and viewed under a Nikon fluorescence microscope (model Eclipse E400).

To view viral spread in striatal neurons, images were captured at 4× magnification for e-YFP expression. For cell counting analysis, images from the dorsolateral striatum were taken at 40× magnification. Expression of ChR2-eYFP in cholinergic interneurons was evaluated by counting all ChAT/e-YFP double positive cells. To delineate ChR2-eYFP expression in D2-MSNs, DARPP-32 and e-YFP double positive cells were obtained by merging individual signals using Adobe Photoshop software, as described (Bordia et al., 2016). The proportion of ChR2-eYFP positive D2-MSNs was obtained by calculating the ratio of the number of double positive cells to the total number of DARPP-32 expressing cells in a blinded manner. c-Fos+ cell counting was done at 10× magnification, with cells designated c-Fos+ when they exhibited a clear, intense round or oval red staining in the nucleus. Adobe Photoshop software merged images of cells expressing c-Fos/eYFP was counted manually by a blinded rater. Three striatal sections at A1.4 (range A1.5–1.3) mm, A0.8 (range A0.9–0.7) mm and A0.2 (range 0.3-0.1) mm from bregma were used for cell counting. The mean of 3 sections was averaged for each animal (n = 11=12) and considered an individual observation for statistical analyses. eYFP cell counts indicated that variability in striatal viral expression among mice averaged 24% for ChAT-Cre mice (n = 12) and 30% (n = 11) for D2-Cre mice.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were performed with GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA) using t-tests, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. The values expressed are the mean ± SEM of the indicated number of mice.

Results

Nicotine treatment reduces haloperidol-induced VCMs in control mice

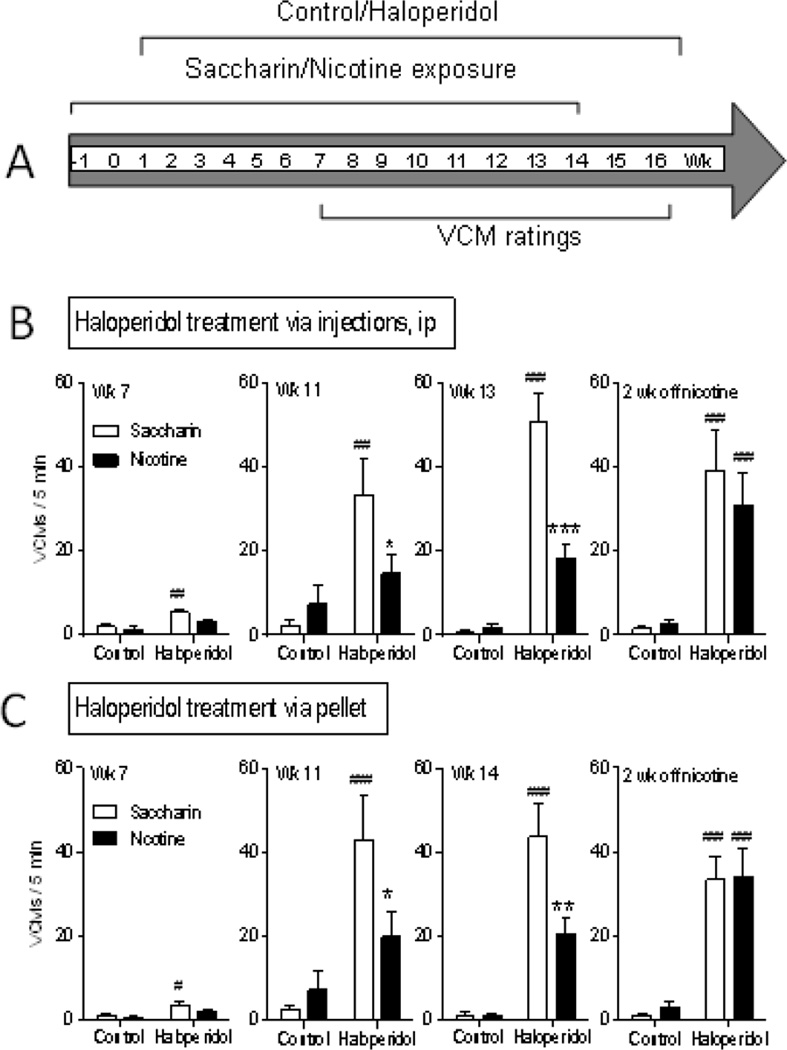

We first tested if nicotine treatment reduced haloperidol-induced TD in mice as it had in rats (Bordia et al., 2012), since genetically modified mice were to be used in the present experiments. Haloperidol injection and pellet administration alone significantly increased VCMs by 7 wk of treatment with a plateau by wk 11–14 (Fig. 1B, C). Nicotine administration decreased VCMs with either treatment mode (~50%) throughout the treatment period. Nicotine removal (Fig. 1B, C right panels) resulted in an increase in haloperidol-induced VCMs to the levels observed in mice receiving only saccharin. These studies demonstrate that the nicotine-induced decline in VCMs is drug-induced.

Fig. 1.

Nicotine treatment reduces TD in mice. A. Treatment timeline of control/haloperidol and saccharin/nicotine treatment in mice. Haloperidol was administered for 16 wk with haloperidol-induced VCMs rated for 5 min once weekly. Chronic haloperidol increased VCMs, whether administered via daily injection (B) or via a 90-day release implantable pellet (C). Nicotine treatment reduced haloperidol-induced VCMs with both modes of haloperidol administration (B, C) with a significant effect by 11 wk of nicotine dosing. Two wk of nicotine removal increased haloperidol-induced VCMs to saccharin-treated levels (B, C right panels). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of 5–7 mice per group. Significance of difference from own control group: #p ≤ 0.05, ##p ≤ 0.01, ### p ≤ 0.001; significance of difference from haloperidol-treated saccharin group *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01 ***p ≤ 0.001 using two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test.

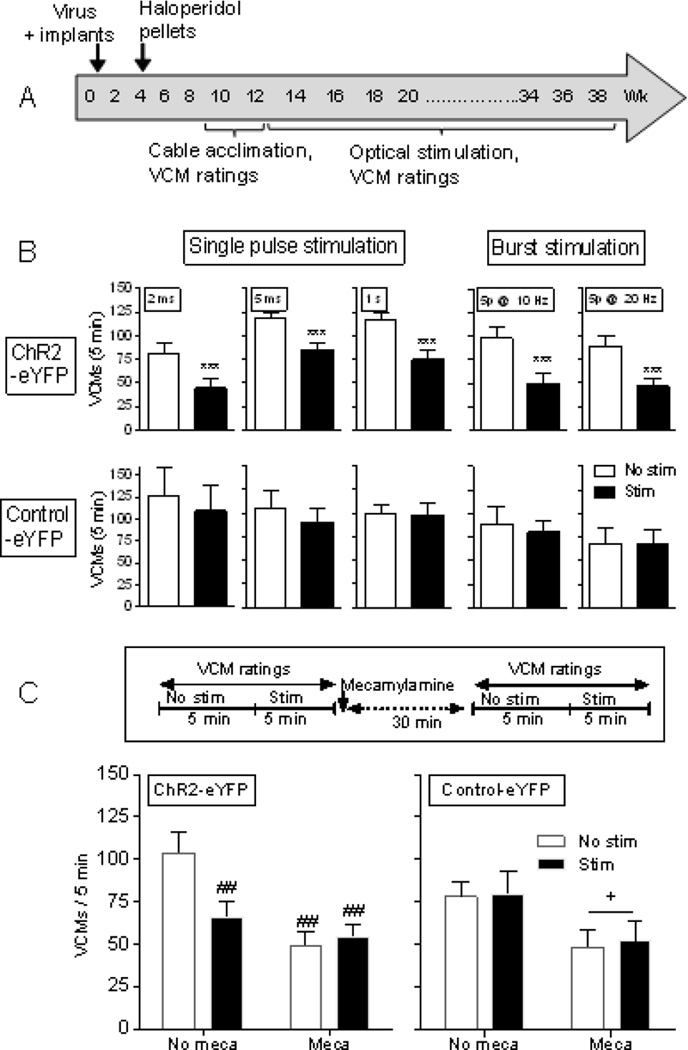

Optical stimulation of striatal cholinergic interneurons reduces haloperidol-induced VCMs

ChAT-Cre mice selectively expressing ChR2 in striatal cholinergic neurons were administered haloperidol via pellets, as this mode of treatment is less stressful than chronic injection (Fig. 2A). The mice were initially rated for VCMs starting at wk 7 or 9, that is, 3 or 5 wk after implantation of the haloperidol releasing pellets. For the optical stimulation experiments, the mice were rated first for 5 min in the absence (No stim) and then for 5 min with stimulation (Stim). Single pulse stimulation (2 ms, 5 ms, 1s), with a 0.5 s off stimulation period between pulses, significantly decreased haloperidol-induced VCMs (Fig. 2B top left panels). Declines were also observed with burst stimulation (5 p @ 10 Hz or 5 p @ 20 Hz delivered with a 0.5 s off stimulation period between bursts) that may more closely resemble physiological firing (Fig. 2B top right panels) (Aosaki et al., 1995; Raz et al., 1996; Wilson et al., 1990). There was no decrease in VCMs with stimulation in control-eYFP mice (Fig. 2B bottom panels).

Fig. 2.

Optical stimulation of striatal cholinergic interneurons reduces haloperidol-induced VCMs via a nAChR-mediated mechanism. (A) ChAT-Cre mice were bilaterally injected with virus expressing ChR2-eYFP or control-eYFP into the striatum, and optic fiber placement done as in the timeline. They were then administered haloperidol via subcutaneously implanted slow-release pellets and VCM ratings initiated 4 wk later in the absence (No stim) and presence of stimulation (Stim). (B) Both single pulses (2 ms, 5 ms, 1s) for 5 min (left panels) and burst stimulation (5 p @ 10 Hz or 5 p @ 20 Hz) for 5 min (right panels) decreased haloperidol-induced VCMs. There was no decrease in VCMs with stimulation in mice expressing control-eYFP. (C) Haloperidol-treated ChAT-Cre expressing ChR2-eYFP or control-eYFP were rated for VCMs with and without optical stimulation (5 ms single pulse for 5 min). They were then injected with mecamylamine (1.0 mg/kg). Thirty min later, they were again rated for VCMs with (Stim) and without (No stim) optical stimulation. Stimulation or mecamylamine alone decreased VCMs to a similar extent, with no further decline in VCMs with combined stimulation and mecamylamine (Meca) treatment (left panel), suggesting the effect of stimulation is nAChR-mediated. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of 4–8 mice. In mice expressing control-eYFP there was a significant main effect of mecamylamine treatment (+p ≤ 0.05) but no effect of optical stimulation (right panel). Significantly different from No stim, ***p ≤ 0.001 using a paired t-test. Significantly different from No stim No meca, ##p ≤ 0.01 using two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test.

We next evaluated a role for the nicotinic cholinergic system using the general nicotinic receptor (nAChR) blocker mecamylamine (Fig. 2C). Haloperidol-treated ChAT-Cre mice expressing ChR2-eYFP or control-eYFP were optically stimulated (5 ms single pulses) and rated for VCMs. They were then injected with mecamylamine (1.0 mg/kg) and again rated for VCMs with and without optical stimulation 30 min later. Stimulation or mecamylamine alone decreased VCMs to a similar extent, with no further decline in VCMs with stimulation plus mecamylamine (Fig. 2C left panel). The similar decline with stimulation plus mecamylamine injection as with either treatment alone suggests that stimulation induces it effect via nAChRs. In control-eYFP mice, there was a significant main effect of mecamylamine but no effect of optical stimulation, as expected in the absence of ChR2 expression (Fig. 2C right panel).

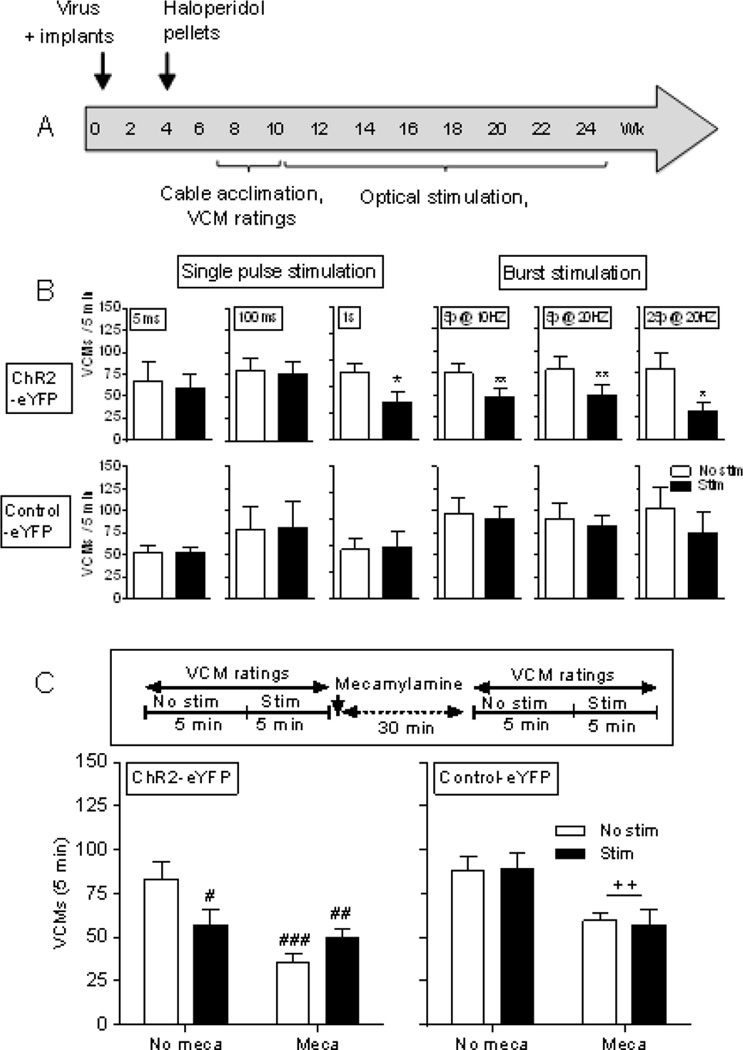

Optical stimulation of striatal D2 MSNs reduces haloperidol-induced VCMs

We next initiated studies with Adora2a-Cre mice expressing ChR2 in striatal D2 MSNs. They were subcutaneously implanted with haloperidol-releasing pellets and rated for VCMs several wk later in the absence (No stim) and presence of stimulation (Stim) (Fig. 3A). Declines in VCMs were observed with stimulation consisting of single pulses (1 s) delivered with a 0.5 s off stimulation period between pulses (Fig. 3B top left panels), and with several burst stimulation paradigms including 5 p @ 10 Hz, 5 p @ 20 Hz or 25 p @ 20 Hz, with a 0.5 s off stimulation period between bursts (Fig. 3B top right panels). There was no decrease in VCMs with stimulation in mice expressing control-eYFP, indicating a direct role of D2 MSN activation (Fig. 3B bottom).

Fig. 3.

Optical stimulation of striatal D2 MSNs reduces haloperidol-induced VCMs via a nAChR-mediated mechanism. (A) Timeline. Adora2a-Cre mice were bilaterally injected with virus expressing ChR2-eYFP or control-eYFP into the striatum, and optic fiber placement done. Haloperidol was subsequently administered via a 90-day release implantable pellet. Four wk later, the mice were rated for VCMs in the absence (No stim) and presence of stimulation (Stim). (B) Declines in VCMs were observed with single pulses of 1 s for 5 min and burst stimulation paradigms (5 p @ 10 Hz, 5 p @ 20 Hz or 25 p @ 20 Hz) for 5 min. Stimulation did not decrease VCMs in mice expressing control-eYFP. (C) Haloperidol-treated Adora2a-Cre expressing ChR2-eYFP or control-eYFP were rated for VCMs with and without optical stimulation (1 s single pulse for 5 min). They were then injected with mecamylamine (1.0 mg/kg). Thirty min later, they were again rated for VCMs with and without optical stimulation. Stimulation or mecamylamine (Meca) alone decreased VCMs to a similar extent, with no further decline in VCMs with combined stimulation and mecamylamine treatment (left panel), suggesting the effect of stimulation occurs via nAChRs. In mice expressing control-eYFP there was a significant main effect of mecamylamine (++p ≤ 0.01) but no effect of optical stimulation (right panel). Each bar is the mean ± SEM of 4–8 mice. Significantly different from No stim, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01 using a paired t-test. Significantly different from No stim No meca, #p ≤ 0.05, ##p ≤ 0.01, ###p ≤ 0.001 using two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test.

To investigate a nicotinic cholinergic involvement, we tested the effect of mecamylamine (Fig. 3C). Haloperidol-treated Adora2a-Cre mice expressing ChR2-eYFP or control-eYFP were rated for VCMs with and without optical stimulation (1 s single pulse). They were then injected with mecamylamine (1.0 mg/kg), and again rated for VCMs with and without optical stimulation 30 min later. Stimulation or mecamylamine alone decreased VCMs to a similar extent, with no further decline with combined stimulation and mecamylamine treatment (Fig. 3C left panel). This similarity in response with stimulation alone, mecamylamine alone and the combined treatment suggests that the stimulation-induced decline in haloperidol-induced VCMs involves an interaction at nAChRs. There was no effect of optical stimulation (Fig. 3C right panel) in mice expressing control-eYFP, as expected if ChR2 is not expressed.

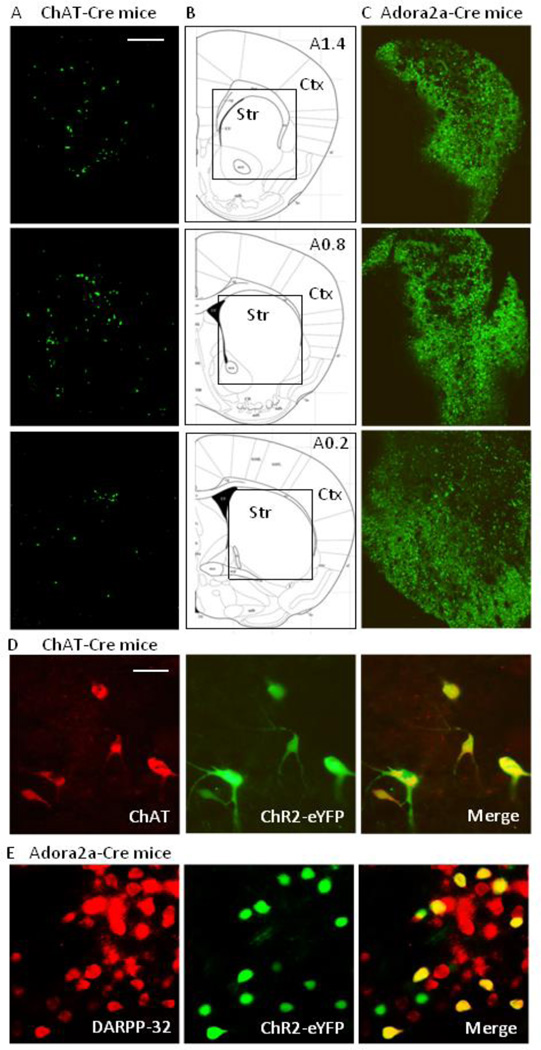

Selective expression of ChR2-eYFP

Expression of ChR2-eYFP in cholinergic neurons was evaluated in the striatum (level A1.4 to A0.2) on both sides of the brain injected with virus, with the data shown depicting expression on the right side (Fig. 4A). ChR2-eYFP was localized throughout the striatum, but not cortex. Fig. 4D demonstrates that ChR2-eYFP is localized to striatal ChAT+ neurons.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of ChR2-eYFP in striatum of transgenic mice. (A) Expression of ChR2-eYFP (green) in the right striatum (A1.4 to A0.2) of ChAT-Cre mice. (B) The boxed area in the schematics are depicted in the images in (A) and (C). (C) Expression of ChR2-eYFP (green) in the right striatum (A1.4 to A0.2) of D2 MSNs (Adora2a-Cre mice). Scale bar = 500 µm. Ctx, cortex; Str, striatum. (D) Expression of ChR2-eYFP in striatal cholinergic interneurons of ChAT-Cre mice and (E) expression of ChR2-eYFP in striatal MSNs of Adora2a-Cre mice. Images depict localization of ChAT (red, left panel D) or DARPP-32 (red, left panel E) immunofluoresence, ChR2-eYFP (green, middle panel) and the merge (yellow, right panel). Scale bar = 20 µm.

Expression of ChR2-eYFP was also evaluated in striatal D2 MSNs (level A1.4 to A0.2), with the data shown for the right side only. For these studies, we used an adenosine A2a receptor Cre mouse model that specifically targets D2 MSNs on the indirect pathway. Thus, although it is known that A2A receptors may co-localize with D2 receptors on other neurons (Tozzi et al., 2011), it is unlikely that ChR2 is expressed on such neurons in the present study. Fig. 4C shows that ChR2 was selectively present on striatal D2 MSNs with no localization in cortex or other adjacent brain regions. Co-localization studies (Fig. 4E) showed that ChR2-eYFP was expressed in about of 40% striatal DARPP-32+ neurons, consistent with findings that only a subpopulation of striatal MSNs are D2 expressing (Bertran-Gonzalez et al., 2008).

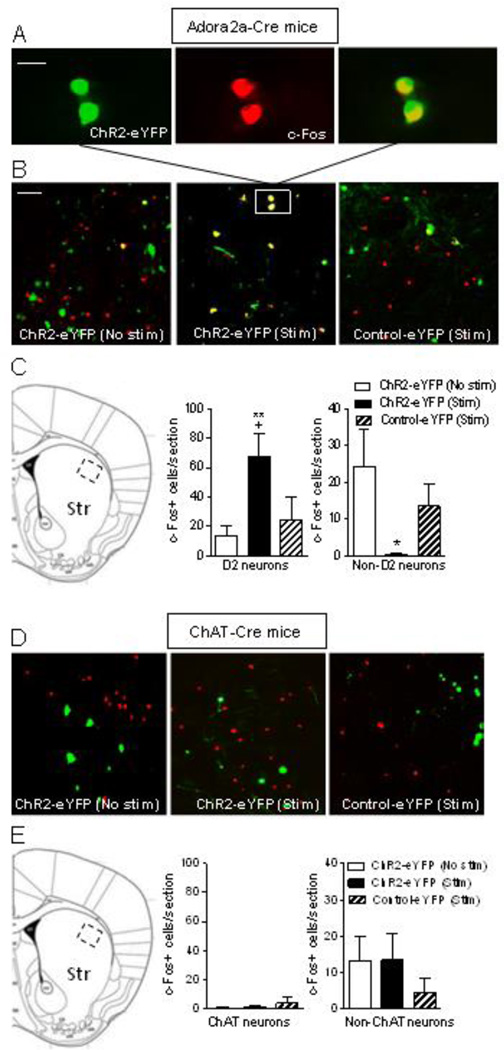

Activation of striatal D2 MSNs in haloperidol-treated Adora2a-Cre mice increases c-Fos+ D2 MSNs and decreases c-Fos+ non-D2 MSNs

To determine if alterations in haloperidol-induced TD are associated with changes in striatal c-Fos, haloperidol-treated Adora2a-Cre mice expressing ChR2-eYFP or control-eYFP were optically stimulated (ChR2-eYFP Stim and control-eYFP Stim). We used single pulses of 1 s duration, the minimal stimulation that reduces TD, with a 0.5 s off stimulation period between pulses. The mice were then killed immediately after 5 min of stimulation. This time point was selected because VCMs are decreased during the 5 min stimulation period; thus any resulting changes in c-Fos may be linked to stimulation-induced declines in VCMs. There was also a subset of ChR2-eYFP mice that received haloperidol but were not optically stimulated (ChR2-eYFP No stim). c-Fos activation is evident in D2 MSNs (Fig. 5A). A significant increase in the number of c-Fos+ striatal D2 MSNs and decrease in c-Fos+ non-D2 MSNs is observed with optical stimulation in haloperidol-treated mice. Thus changes in c-Fos+ MSNs may play a role in the expression of TD (Fig. 5B, C).

Fig. 5.

Activation of striatal D2 expressing GABAergic MSNs in haloperidol-treated Adora2a-Cre mice increases c-Fos+ D2 MSNs and decreases c-Fos+ non-D2 MSNs. Adora2a-Cre mice expressing ChR2-eYFP or control-eYFP were implanted with haloperidol pellets to induce TD. They were then optically stimulated (ChR2-eYFP Stim) with single pulses (1 s) for 5 min, a condition that reduces TD. There was also a subset of ChR2-eYFP mice that received haloperidol but were not optically stimulated (ChR2-eYFP No stim). The mice were then killed immediately after stimulation, the brain quickly removed and fixed for immunofluorescence. A, depicts neurons in the boxed area in B showing cells immunostained with ChR2-eYFP (green, left), c-Fos (red, middle) and the merge (right). B, provides images of eYFP (green), c-Fos (red) and eYFP+c-Fos (yellow) positive neurons of unstimulated ChR2-eYFP mice (No stim, left), ChR2-eYFP mice with stimulation (Stim, middle) and control-eYFP mice with stimulation (Stim, right). Quantitation of the data is provided in C, with the boxed area in the image depicting the dorsolateral striatal area counted. D and E, respectively, depict images and quantitation of the effect of cholinergic neuron activation in haloperidol-treated ChAT-Cre mice; no changes were observed in c-Fos+ ChAT neurons with stimulation. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of n = 4–5 ChR2-eYFP (No stim), n = 4 ChR2-eYFP (Stim) and n = 3 Control-eYFP (Stim) mice. Significantly different from ChR2-eYFP (No stim), *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01; from Control-eYFP (Stim), +p ≤ 0.05 using a one-way ANOVA followed by a Dunnett’s post hoc test. Scale bar = 20 µm and 100 µm in the upper and middle panel, respectively.

Similar experiments were done in which haloperidol-treated ChAT-Cre mice were optically stimulated (ChR2-eYFP Stim and control-eYFP Stim) with single pulses (5 ms) delivered with a 0.5 s off stimulation period between stimuli; this stimulation paradigm had reduced TD. There was also a subset of ChR2-eYFP mice that received haloperidol but were not optically stimulated (ChR2-eYFP No stim). No changes were observed with optical stimulation in c-Fos+ ChAT or non-ChAT neurons with stimulation in haloperidol-treated ChAT-Cre mice (Fig. 5D, 5E).

Discussion

This study is the first to use optogenetics to gain insight into the striatal neuronal cell subtypes that underlie haloperidol-induced TD. The results show that selective bilateral activation of striatal cholinergic interneurons using single or burst stimulation paradigms decreases haloperidol-induced VCMs. In addition, activation of striatal D2 MSNs reduced VCMs. Thus, both cholinergic interneurons and D2 MSNs regulate TD. Nicotine treatment and optical stimulation of cholinergic interneurons or of D2 MSNs all decreased VCMs by ~50%. This observation, coupled with studies showing that the nicotinic blocker mecamylamine reduces VCMs to a similar extent as optical stimulation, suggests that nAChR desensitization may represent a common mechanism underlying the regulation of TD by striatal cholinergic interneurons and D2 MSNs.

We focused on the striatum because this subcortical region plays a major role in regulating motor function and is also critically involved in the abnormal involuntary movements that develop with antipsychotic treatment (Gittis and Kreitzer, 2012; Loonen and Ivanova, 2013; Teo et al., 2012). The striatum contains a heterogeneous mix of neuronal cell types, including cholinergic interneurons and D2 MSNs. We first investigated a role for striatal cholinergic interneurons as previous studies suggested a role for these neurons (Kelley and Roberts, 2004) and because our more recent work showed that nicotinic cholinergic drugs can modulate antipsychotic induced-induced VCMs (Bordia et al., 2013; Quik et al., 2014). Selective activation of cholinergic interneurons decreased haloperidol-induced VCMs using tonic or burst stimulation paradigms, with a ~50% decrease with either mode of optical stimulation. Thus, the current experiments provide direct evidence that striatal cholinergic interneurons regulate TD.

Because chronic nicotine administration reduced haloperidol-induced VCMs, we next investigated if nAChR blockade affected the decline in VCMs with optical stimulation of striatal cholinergic neurons. The nAChR antagonist mecamylamine by itself decreased VCMs, while mecamylamine plus cholinergic interneuron stimulation diminished VCMs to a similar extent as either condition alone. A possible explanation for this similarity in response with nicotine, mecamylamine or optical stimulation may involve nAChR desensitization. Agonists such as nicotine are thought to induce initial receptor activation, quickly followed by a receptor desensitization block (Giniatullin et al., 1999; Paradiso and Steinbach, 2003; Picciotto et al., 2008). Mecamylamine would directly inhibit nAChR function since it is a nAChR antagonist. Cholinergic neuron activation may block function because of desensitization due to excess ACh release. This idea is supported by striatal microdialysis studies showing that nM concentrations of ACh are released upon stimulation; this would be sufficient to desensitize nAChRs, a process that occurs in the nM range over a millisecond time frame (Consolo et al., 1987; Kawashima et al., 1991; Mohr et al., 2015).

There are also other possibilities to explain the nAChR-mediated reduction in VCMs. For instance, there were differences in experimental paradigms between the studies involving nicotine and mecamylamine administration. Nicotine was given on a chronic basis prior to and during VCM development whereas the nAChR blocker mecamylamine was administered acutely after VCMs were established. Thus, effects of nicotine may reflect an action of the drug on VCM development (neuronal adaptation), while effects of mecamylamine on VCMs may due to more acute molecular/cellular events.

Although nAChR desensitization may play a role in the experimentally induced reduction in VCMs, it was somewhat unexpected that all single-pulse and burst stimulation paradigms yielded similar declines in VCMs. One possibility is that desensitization underlies effects observed with longer duration single-pulse and burst stimulation but that alternate mechanisms are responsible for the short duration single-pulse mediated decline. For instance, short (≤ 5 ms) single-pulse stimulation of ChAT interneurons may activate muscarinic receptors to mediate a decrease in VCMs. Muscarinic receptors, including M1 to M5, are extensively localized on numerous neuronal cell types in the striatum. Acetylcholine released after optical stimulation interacts with M2 and M4 receptors on DA terminals to facilitate DA release (Threlfell et al., 2010). This released DA can in turn act on D1 and D2 receptor-expressing MSNs to modulate their activity. However, M1 and M4 muscarinic receptors are also present on MSNs where they may counteract the action of DA. Stimulation of M1 receptors on D1 and D2 MSNs induces neuronal excitation, while activation of M4 receptors, predominantly expressed on D1 MSNs, decreases neuronal activity (Brown, 2010; Goldberg et al., 2012; Pisani et al., 2007). Consequently, muscarinic receptor activation may inhibit D1 MSN but stimulate D2 MSN activity. In addition, muscarinic receptors expressed on other neuronal populations (ie. glutamatergic and serotonergic terminals) may modulate striatal function/circuitry and consequently the expression of abnormal involuntary movements (Goldberg et al., 2012; Quik and Wonnacott, 2011). Furthermore, our studies showed that muscarinic receptors modulate L-dopa-induced dyskinesias following similar optogenetic manipulations (Bordia et al., 2016). In addition, M4 activation has been shown to reduce L-dopa induced dyskinesias while a muscarinic receptor antagonist decreases other drug-induced abnormal involuntary movements (Ding et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2015). Thus, an acetylcholine interaction with muscarinic receptors expressed on D2 MSNs could regulate MSN output to reduce VCMs. On the other hand, the beneficial effect of antimuscarinic drugs in TD has proved conflicting in clinical trials (Aia et al., 2011; Jankelowitz, 2013; Jeste and Wyatt, 1982; Seigneurie et al., 2016), with several studies reporting an improvement in TD with discontinuation of antimuscarinic drugs (Burnett et al., 1980; Greil et al., 1984; Klawans and Rubovits, 1974).

Since cholinergic receptors exert multiple regulatory activities on striatal cell functions, it is also conceivable that activation of ChAT neurons enhances dopaminergic function to modulate dopamine release and ultimately alter VCM expression (Cachope et al., 2012; Threlfell et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2009). To investigate this possibility, we evaluated the role of D2 MSNs, the primary output neurons of the indirect striatal pathway that regulate basal ganglia function and motor behavior (Freeze et al., 2013; Kravitz et al., 2010; Lenz and Lobo, 2013). We focused on D2 MSNs as TD develops because of the D2 receptor blocking characteristics of antipsychotic drugs. We used Adora2a-Cre mice which allow for the selective expression of ChR2 in neurons expressing the adenosine A2a (Adora2a) receptor, with these same neurons also having D2 receptors (Fink et al., 1992; Freeze et al., 2013). Our results show that the lower duration single pulse stimulation paradigms (5 ms and 100 ms) did not affect haloperidol-induced VCMs, but that 1 s pulse stimulation for 5 min significantly decreased haloperidol-induced VCMs. All the burst firing stimulation regimens also yielded a decrease in VCMs. Since 1 s optical pulses result in burst firing (Freeze et al., 2013), these combined data suggest that burst firing of D2 MSNs underlies the decline in haloperidol-induced VCMs.

To examine the possibility that the cholinergic system influenced the D2 MSN-induced regulation of VCMs, we investigated the effect of the nAChR antagonist mecamylamine. Activation of striatal D2 MSNs attenuated VCMs to a similar extent (~50%) as mecamylamine alone. Additionally, combined treatment with optical stimulation and mecamylamine led to a decline in VCMs that resembled each treatment on its own. These data suggest that cholinergic interneurons and D2 MSNs may be linked in their regulation of TD. The nature of this regulation is currently not known. It is most likely not via a direct action of released ACh on D2 MSNs since these neurons lack nAChRs (Jones et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2002). Rather, striatal nAChRs appear to be expressed presynaptically on afferents as evidenced by the limited expression of nAChR subunits mRNAs in striatum (Marks et al., 1992; Wada et al., 1989). α4β2* and α6β2* nAChRs are present on nigrostriatal dopamine terminals (Quik and Wonnacott, 2011), with α4β2* nAChRs also residing on serotonergic terminals (Reuben and Clarke, 2000; Schwartz et al., 1984) and fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons to enhance D2 MSN activity via feedforward inhibition (Grilli et al., 2009; Luo et al., 2013; McClure-Begley et al., 2014). Functional α4β2* nAChRs have not been identified on MSNs; thus, the low density α4 and β2 nAChR mRNA transcripts present within MSNs are most likely not expressed as receptor protein (Azam et al., 2002). α7 nAChRs are located on glutamate afferents from the cortex, as well as on MSNs, fast-spiking interneurons, and cholinergic interneurons in mouse striatum (Quik and Wonnacott, 2011). However, the α7 nAChR levels are generally low (Marks et al., 1986). These combined observations suggest that modulation of nAChRs on other striatal systems or in other brain areas such as the cortex or thalamus consequently influences D2 MSN function to regulate TD.

A question that arises is whether the effect of optical stimulation is selective for TD or if other movement such as haloperidol-induced catalepsy is also affected. Although such studies remain to be done, our previous work shows that optical stimulation reduces another type of drug-induced abnormal involuntary movement L-dopa-induced dyskinesias, with no effect on parkinsonism (Bordia et al., 2016). Selectivity was thus observed under these conditions.

Immediate early genes such as c-Fos are important mediators in a multitude of physiological and pathological processes, including those involving CNS dopaminergic systems (Ebihara et al., 2011; Paul et al., 1992; Robertson et al., 1989). We therefore investigated whether alterations in haloperidol-induced TD may be associated with changes in striatal c-Fos. Results show that the number of c-Fos+ D2 MSNs was similar in unstimulated ChR2-eYFP and control-eYFP mice. An optical stimulation duration that decreased VCMs was associated with a significant increase in striatal c-Fos+ D2 MSNs. Interestingly, there was a significant decrease in the number non-D2 c-Fos+ MSNs with stimulation. These most likely represent D1 receptor-expressing MSNs as they comprise about half of the MSN population in striatum (Bertran-Gonzalez et al., 2008). In fact, D1 MSNs may be involved in TD as studies have shown that some D1 receptor agonists but not others may trigger VCMs in rats (Rosengarten et al., 1993; Van Kampen and Stoessl, 2000). Furthermore, there is also evidence that D2 MSNs form recurrent collateral connections with D1 MSNs and modulate their activity (Taverna et al., 2008). Thus, changes in c-Fos in both D1 and D2 MSNs may contribute to the optical stimulation-induced decrease in VCMs.

In summary, our findings show that the selective activation of striatal cholinergic interneurons and D2 MSNs improve haloperidol-induced VCMs in a mouse TD model. This improvement was also observed with the nAChR blocker mecamylamine suggesting that alterations in cholinergic function represent a common mechanism in TD regulation. In addition, these data suggest that nAChR drugs may be useful for reducing antipsychotic-induced TD.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Striatal cholinergic activation reduces tardive dyskinesia via nicotinic receptors

Striatal D2 neuron activation decreases tardive dyskinesia via nicotinic receptors

Thus, multiple striatal neurotransmitters systems regulate tardive dyskinesia

Nicotinic receptor drugs may reduce antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NS59910. The authors thank Matt McGregor for excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- TD

Tardive dyskinesia

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- *

the asterisk indicates the possible presence of other subunits in the nicotinic receptor complex.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Relevant conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aia PG, Revuelta GJ, Cloud LJ, Factor SA. Tardive Dyskinesia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2011;13:231–241. doi: 10.1007/s11940-011-0117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aosaki T, Kimura M, Graybiel AM. Temporal and spatial characteristics of tonically active neurons of the primate's striatum. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1234–1252. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.3.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam L, Winzer-Serhan UH, Chen Y, Leslie FM. Expression of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit mRNAs within midbrain dopamine neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2002;444:260–274. doi: 10.1002/cne.10138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertran-Gonzalez J, Bosch C, Maroteaux M, Matamales M, Herve D, Valjent E, Girault JA. Opposing patterns of signaling activation in dopamine D1 and D2 receptor-expressing striatal neurons in response to cocaine and haloperidol. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5671–5685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1039-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet PJ, Parent MT, Rompre PH, Levesque D. Relevance of animal models to human tardive dyskinesia. Behav Brain Funct. 2012;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordia T, Campos C, McIntosh JM, Quik M. Nicotinic receptor-mediated reduction in L-dopa-induced dyskinesias may occur via desensitization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333:929–938. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.162396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordia T, Carroll FI, Quik M. Varenicline Markedly Decreases Antipsychotic-induced Tardive Dyskinesia in a Rodent Model. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2013;33:32.07. [Google Scholar]

- Bordia T, McIntosh JM, Quik M. Nicotine reduces antipsychotic-induced orofacial dyskinesia in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340:612–619. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.189100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordia T, Perez XA, Heiss JE, Zhang D, Quik M. Optogenetic activation of striatal cholinergic interneurons regulates L-dopa-induced dyskinesias. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;91:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) in the nervous system: some functions and mechanisms. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;41:340–346. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett GB, Prange AJ, Jr, Wilson IC, Jolliff LA, Creese IC, Synder SH. Adverse effects of anticholinergic antiparkinsonian drugs in tardive dyskinesia. An investigation of mechanism. Neuropsychobiology. 1980;6:109–120. doi: 10.1159/000117742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachope R, Mateo Y, Mathur BN, Irving J, Wang HL, Morales M, Lovinger DM, Cheer JF. Selective activation of cholinergic interneurons enhances accumbal phasic dopamine release: setting the tone for reward processing. Cell reports. 2012;2:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canitano R, Scandurra V. Psychopharmacology in autism: an update. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolo S, Wu CF, Fiorentini F, Ladinsky H, Vezzani A. Determination of endogenous acetylcholine release in freely moving rats by transstriatal dialysis coupled to a radioenzymatic assay: effect of drugs. J Neurochem. 1987;48:1459–1465. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb05686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:414–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Schenk EM. Tardive dyskinesia and new antipsychotics. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:151–156. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f53132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley JJ, Adkins DE, Pratt AL, Quackenbush CR, van den Oord EJ, Moy SS, Wilhelmsen KC, Cooper TB, Bogue MA, McLeod HL, Sullivan PF. Antipsychotic-induced vacuous chewing movements and extrapyramidal side effects are highly heritable in mice. Pharmacogenomics J. 2012;12:147–155. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2010.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffains M, Bergman H. Striatal cholinergic interneurons and cortico-striatal synaptic plasticity in health and disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30:1014–1025. doi: 10.1002/mds.26300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekundy A, Lundblad M, Danysz W, Cenci MA. Modulation of L-DOPA-induced abnormal involuntary movements by clinically tested compounds: further validation of the rat dyskinesia model. Behav Brain Res. 2007;179:76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Won L, Britt JP, Lim SA, McGehee DS, Kang UJ. Enhanced striatal cholinergic neuronal activity mediates L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in parkinsonian mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:340–345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006511108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara K, Ishida Y, Takeda R, Abe H, Matsuo H, Kawai K, Magata Y, Nishimori T. Differential expression of FosB, c-Fos, and Zif268 in forebrain regions after acute or chronic L-DOPA treatment in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2011;496:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink JS, Weaver DR, Rivkees SA, Peterfreund RA, Pollack AE, Adler EM, Reppert SM. Molecular cloning of the rat A2 adenosine receptor: selective co-expression with D2 dopamine receptors in rat striatum. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1992;14:186–195. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeze BS, Kravitz AV, Hammack N, Berke JD, Kreitzer AC. Control of basal ganglia output by direct and indirect pathway projection neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:18531–18539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1278-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giniatullin R, Di Angelantonio S, Marchetti C, Sokolova E, Khiroug L, Nistri A. Calcitonin gene-related peptide rapidly downregulates nicotinic receptor function and slowly raises intracellular Ca2+ in rat chromaffin cells In vitro [In Process Citation] J Neurosci. 1999;19:2945–2953. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-02945.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittis AH, Kreitzer AC. Striatal microcircuitry and movement disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JA, Ding JB, Surmeier DJ. Muscarinic modulation of striatal function and circuitry. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012:223–241. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-23274-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil W, Haag H, Rossnagl G, Ruther E. Effect of anticholinergics on tardive dyskinesia. A controlled discontinuation study. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;145:304–310. doi: 10.1192/bjp.145.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli M, Zappettini S, Raiteri L, Marchi M. Nicotinic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors coexist on GABAergic nerve endings in the mouse striatum and interact in modulating GABA release. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:610–614. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Grady SR, Quik M. Nicotine Reduces L-Dopa-Induced Dyskinesias by Acting at {beta}2 Nicotinic Receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:932–941. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.182949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankelowitz SK. Treatment of neurolept-induced tardive dyskinesia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1371–1380. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S30767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Wyatt RJ. Therapeutic strategies against tardive dyskinesia. Two decades of experience. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:803–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070037008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones IW, Bolam JP, Wonnacott S. Presynaptic localisation of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor beta2 subunit immunoreactivity in rat nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurones. J Comp Neurol. 2001;439:235–247. doi: 10.1002/cne.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima K, Hayakawa T, Kashima Y, Suzuki T, Fujimoto K, Oohata H. Determination of acetylcholine release in the striatum of anesthetized rats using in vivo microdialysis and a radioimmunoassay. J Neurochem. 1991;57:882–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley JJ, Roberts RC. Effects of haloperidol on cholinergic striatal interneurons: relationship to oral dyskinesias. J Neural Transm. 2004;111:1075–1091. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klawans HL, Rubovits R. Effect of cholinergic and anticholinergic agents on tardive dyskinesia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1974;37:941–947. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.37.8.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz AV, Freeze BS, Parker PR, Kay K, Thwin MT, Deisseroth K, Kreitzer AC. Regulation of parkinsonian motor behaviours by optogenetic control of basal ganglia circuitry. Nature. 2010;466:622–626. doi: 10.1038/nature09159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz JD, Lobo MK. Optogenetic insights into striatal function and behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2013;255:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loonen AJ, Ivanova SA. New insights into the mechanism of drug-induced dyskinesia. CNS Spectr. 2013;18:15–20. doi: 10.1017/s1092852912000752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovinger DM. Neurotransmitter roles in synaptic modulation, plasticity and learning in the dorsal striatum. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:951–961. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R, Janssen MJ, Partridge JG, Vicini S. Direct and GABA-mediated indirect effects of nicotinic ACh receptor agonists on striatal neurones. J Physiol. 2013;591:203–217. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.241786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Pauly JR, Gross SD, Deneris ES, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Heinemann SF, Collins AC. Nicotine binding and nicotinic receptor subunit RNA after chronic nicotine treatment. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2765–2784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02765.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Stitzel JA, Romm E, Wehner JM, Collins AC. Nicotinic binding sites in rat and mouse brain: comparison of acetylcholine, nicotine, and alpha-bungarotoxin. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;30:427–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure-Begley TD, Grady SR, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Stitzel JA. Presynaptic GABA Autoreceptor Regulation of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Mediated [H]-GABA Release from Mouse Synaptosomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr F, Krejci E, Zimmermann M, Klein J. Dysfunctional Presynaptic M2 Receptors in the Presence of Chronically High Acetylcholine Levels: Data from the PRiMA Knockout Mouse. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso KG, Steinbach JH. Nicotine is highly effective at producing desensitization of rat alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic receptors. J Physiol. 2003;553:857–871. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.053447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul ML, Graybiel AM, David JC, Robertson HA. D1-like and D2-like dopamine receptors synergistically activate rotation and c-fos expression in the dopamine-depleted striatum in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3729–3742. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-03729.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluso MJ, Lewis SW, Barnes TR, Jones PB. Extrapyramidal motor side-effects of first- and second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:387–392. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Addy NA, Mineur YS, Brunzell DH. It is not "either/or": Activation and desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors both contribute to behaviors related to nicotine addiction and mood. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickar D, Vinik J, Bartko JJ. Pharmacotherapy of schizophrenic patients: preponderance of off-label drug use. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Bernardi G, Ding J, Surmeier DJ. Re-emergence of striatal cholinergic interneurons in movement disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, Park KM, Hrachova M, Mallela A, Huang LZ, McIntosh JM, Grady SR. Role for alpha6 nicotinic receptors in l-dopa-induced dyskinesias in parkinsonian mice. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:450–459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, Wonnacott S. {alpha}6{beta}2* and {alpha}4{beta}2* Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors As Drug Targets for Parkinson's Disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:938–966. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, Zhang D, Perez XA, Bordia T. Role for the nicotinic cholinergic system in movement disorders; therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;144:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz A, Feingold A, Zelanskaya V, Vaadia E, Bergman H. Neuronal synchronization of tonically active neurons in the striatum of normal and parkinsonian primates. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2083–2088. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben M, Clarke PB. Nicotine-evoked [3H]5-hydroxytryptamine release from rat striatal synaptosomes [In Process Citation] Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:290–299. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson GS, Herrera DG, Dragunow M, Robertson HA. L-dopa activates c-fos in the striatum ipsilateral to a 6-hydroxydopamine lesion of the substantia nigra. European journal of pharmacology. 1989;159:99–100. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengarten H, Schweitzer JW, Friedhoff AJ. A subpopulation of dopamine D1 receptors mediate repetitive jaw movements in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;45:921–924. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90140-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RD, Lehmann J, Kellar KJ. Presynaptic nicotinic cholinergic receptors labeled by [3H]acetylcholine on catecholamine and serotonin axons in brain. J Neurochem. 1984;42:1495–1498. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb02818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P. Dopamine D2 receptors as treatment targets in schizophrenia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2010;4:56–73. doi: 10.3371/CSRP.4.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneurie AS, Sauvanaud F, Limosin F. [Prevention and treatment of tardive dyskinesia caused by antipsychotic drugs] Encephale. 2016;42:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Plotkin JL, Francardo V, Ko WK, Xie Z, Li Q, Fieblinger T, Wess J, Neubig RR, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ, Greengard P, Bezard E, Cenci MA, Surmeier DJ. M4 Muscarinic Receptor Signaling Ameliorates Striatal Plasticity Deficits in Models of L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia. Neuron. 2015;88:762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarsy D, Lungu C, Baldessarini RJ. Epidemiology of tardive dyskinesia before and during the era of modern antipsychotic drugs. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;100:601–616. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52014-2.00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverna S, Ilijic E, Surmeier DJ. Recurrent collateral connections of striatal medium spiny neurons are disrupted in models of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5504–5512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5493-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo JT, Edwards MJ, Bhatia K. Tardive dyskinesia is caused by maladaptive synaptic plasticity: a hypothesis. Mov Disord. 2012;27:1205–1215. doi: 10.1002/mds.25107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfell S, Clements MA, Khodai T, Pienaar IS, Exley R, Wess J, Cragg SJ. Striatal Muscarinic Receptors Promote Activity Dependence of Dopamine Transmission via Distinct Receptor Subtypes on Cholinergic Interneurons in Ventral versus Dorsal Striatum. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3398–3408. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5620-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfell S, Lalic T, Platt NJ, Jennings KA, Deisseroth K, Cragg SJ. Striatal dopamine release is triggered by synchronized activity in cholinergic interneurons. Neuron. 2012;75:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrone P, Remington G, Kapur S, Nobrega JN. The relationship between dopamine D2 receptor occupancy and the vacuous chewing movement syndrome in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165:166–171. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1259-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrone P, Remington G, Nobrega JN. The vacuous chewing movement (VCM) model of tardive dyskinesia revisited: is there a relationship to dopamine D(2) receptor occupancy? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:361–380. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kampen JM, Stoessl AJ. Dopamine D(1A) receptor function in a rodent model of tardive dyskinesia. Neuroscience. 2000;101:629–635. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada E, Wada K, Boulter J, Deneris E, Heinemann S, Patrick J, Swanson LW. Distribution of alpha 2, alpha 3, alpha 4, and beta 2 neuronal nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in the central nervous system: a hybridization histochemical study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;284:314–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.902840212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CJ, Chang HT, Kitai ST. Firing patterns and synaptic potentials of identified giant aspiny interneurons in the rat neostriatum. J Neurosci. 1990;10:508–519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-02-00508.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SW, Morgenstern H, Saksa JR, Walsh BC, Sullivan MC, Money R, Hawkins KA, Gueorguieva RV, Glazer WM. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with atypical versus conventional antipsychotic medications: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:463–474. doi: 10.4088/JCP.07m03890yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Doyon WM, Clark JJ, Phillips PE, Dani JA. Controls of Tonic and Phasic Dopamine Transmission in the Dorsal and Ventral Striatum. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:396–404. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.056317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Wilson CJ, Dani JA. Cholinergic interneuron characteristics and nicotinic properties in the striatum. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:590–605. doi: 10.1002/neu.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]