Abstract

Racial disparities in health among African American men in the United States are appalling. African American men have the highest mortality and incidence rates from colorectal cancer compared with all other ethnic, racial, and gender groups. Juxtaposed to their white counterparts, African American men have colorectal cancer incidence and mortality rates 27% and 52% higher, respectively. Colorectal cancer is a treatable and preventable condition when detected early, yet the intricate factors influencing African American men’s intention to screen remain understudied. Employing a nonexperimental, online survey research design at the Minnesota State Fair, the purpose of this study was to explore whether male role norms, knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions influence intention to screen for colorectal cancer among 297 African American men. As hypothesized, these Minnesota men (ages 18 to 65) lacked appropriate colorectal cancer knowledge: only 33% of the sample received a “passing” knowledge score (85% or better). In a logistic regression model, the three factors significantly associated with a higher probability of obtaining colorectal cancer screening were age, perceived barriers, and perceived subjective norms. Findings from this study provide a solid basis for informing health policy and designing health promotion and early-intervention colorectal cancer prevention programs that are responsive to the needs of African American men in Minnesota and beyond.

Keywords: colorectal neoplasms, early detection of cancer, men’s health, minority health, prevention and control

Introduction

Of cancers affecting men and women, colorectal cancer (CRC) remains the third leading cause of new cancer cases and cancer-related deaths for African Americans in the United States (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2014, 2016). CRC disparities persist as African Americans exhibit the highest incidence and mortality rates among all ethnic/racial groups in the United States (ACS, 2014, 2016). Though one of the most preventable and treatable cancers, African American men have CRC mortality and incidence rates 52% and 27% higher than White men (ACS, 2014, 2016).

Although heart disease frequently trends as the leading cause of death for African American men nationally, cancer has been the leading cause for African American men in Minnesota since 2008 (ACS, 2011). Of cancers affecting African American men in Minnesota, CRC is the second leading killer and third most common (prostate cancer is most common, followed by lung cancer; ACS, 2011, 2016; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). Although the average statewide rate of CRC screening (CRCS) in Minnesota is 71%, data released by MN Community Measurement (2016) revealed African Americans in Minnesota continue to have CRCS rates significantly below the statewide average (57%) compared with whites (73%). Differences in access to high-quality routine screening along with lack of timely diagnosis and treatment are well-documented factors shaping such disparity. Especially among African American men, screening uptake is relatively low and remains poorly understood (Brittain, Loveland-Cherry, Northouse, Caldwell, & Taylor, 2012; May et al., 2014, Rim, Joseph, Steele, Thompson, & Seeff, 2011).

CRC incidence trends vary by age, but the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF; 2008) recommends routine screening at age 50 for all men at average risk using a combination of the following: fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) annually, flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, or colonoscopy every 10 years. CRC incidence is declining among adults >age 50, but increasing among those younger than 50 years (ACS, 2014). Some providers have lowered their recommended screening age for African Americans to 45 years (Agrawal et al., 2005; Rex et al., 2009). For each cancer stage category (i.e., localized, regional, and distant), Bailey et al. (2015) identified a steady decline in CRC incidence among patients ≥50 years since 1975, but the opposite trend was noted for patients younger than age 50. Based on current trends, Bailey and colleagues (2015) predict CRC incidence rates among patients aged 20 to 34 years will increase 38% and 90%, respectively, by 2020 and 2030. These trends are not fully understood, but Siegel, Jemal, and Ward (2009) suggest they may stem from unfavorable dietary patterns and/or increased obesity prevalence in both children and young adults. The lack of research explaining this increasing CRC incidence among young adults, African American men included, highlights an urgent need to investigate in more detail factors that shape screening intentions among those younger than 50 years.

Among a sample of African American men ages 18 to 65 residing in Minnesota, the purpose of this study was to explore whether male role norms (MRN), knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions were associated with intention to screen for CRC. Employing a survey design and collecting data at the 2014 Minnesota State Fair, the central hypothesis was MRN influenced these African American men’s intentions to screen for CRC, above and beyond (i.e., independent of) their knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of subjective norms and barriers. The authors also hypothesized these men lacked adequate knowledge and espoused negative attitudes toward CRCS. Research supports the current hypotheses, linking masculinity (MRN) to African American men’s health behavior, mortality, and health care use (Courtenay, 2000; Rogers, Goodson, & Foster, 2015; Wade, 2009; Wade & Rochlen, 2013). Furthermore, hypotheses for this study were formulated on the basis of recommendations that to improve CRCS rates among African Americans, studies should address elements of cultural identity, CRCS beliefs, and subjective norms (Brittain et al., 2012; Rogers et al., 2015).

Conceptual Framework

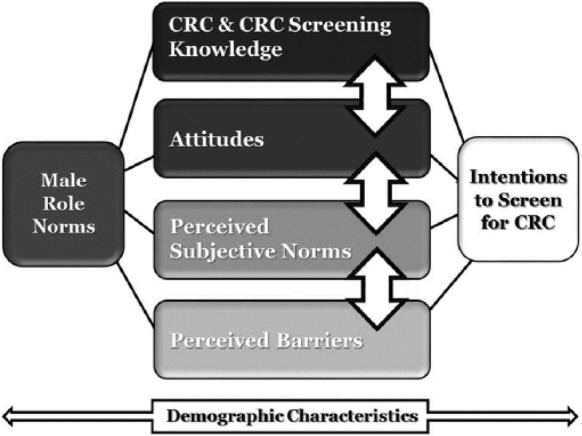

Using the theory of planned behavior (TPB), health behavior studies suggest demographic factors, perceived risk, and previous screening experience may not only affect behavior and intention, but attitudes, perceptions, and subjective norms associated with cancer screening (Roncancio, Ward, & Fernandez, 2013; Smith, Simpson, Trevena, & McCaffery, 2014). Yet, the TPB does not explicitly propose cultural values as factors influencing intention. Accordingly, a conceptual framework developed by Rogers and Goodson (2014) that integrated TPB concepts with MRN guided the current study (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Levant, Hall, & Rankin, 2013). MRN were included in the model and operationalized as behaviors and attributes men should embrace based on sociocultural norms (Thompson & Pleck, 1986). Measures of MRN assess the degree to which African American men agree or disagree with an array of dominant cultural norms of masculinity (Levant & Richmond, 2007).

Figure 1 postulates MRN and four other factors influence an African American man’s intention to obtain CRCS: knowledge, attitudes, perceived subjective norms, and perceived barriers. Knowledge is the awareness or understanding—gained through experience or study—of CRC and three recommended early detection screening practices (i.e., FOBT, sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy). The attitudinal component refers to an African American man’s favorable or unfavorable beliefs and values associated with CRCS participation. An African American male’s perception of how his social support network values CRCS defines the perceived subjective norms factor. Perceived barriers, originally added by Ajzen (1991) to the TPB as perceived behavioral control, accounts for factors outside an African American male’s control that may influence his intent to screen for CRC. Demographic characteristics are also part of the model and include age, educational level, marital status, household income, work status, religious preference, and residence, among others. These factors were included as control variables in analyses since research suggests demographic variables influence African American men’s CRC perceptions, masculinity, and CRCS uptake (ACS, 2014; Gimeno García, 2012).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of factors influencing intentions to screen for colorectal cancer (CRC) among African American men.

Method

Study Design and Samples

Utilizing a sample of African American men residing in Minnesota, this study was conceptually designed to examine factors influencing their intentions to obtain CRCS (see Figure 1). A convenience sampling plan was used, during the last two weekends (Friday-Sunday) in August 2014 and Labor Day, September 1, 2014, to recruit men attending the Minnesota State Fair who: (a) were adults between ages 18-65; (b) self-described as African American; (c) resided in Minnesota; and (d) were able to understand and speak English. A sample of 344 African American men completed the online survey on Apple iPads; 297 met full inclusion criteria after missing data were assessed.

Recruitment

In order to encourage individuals to visit the study site, participants were recruited for the study with handbills and flyers distributed at cancer- and CRC-focused sporting events, gastroenterology centers, ambulatory surgery centers, online social networks (e.g., Facebook), predominantly African American–serving barbershops, local newspapers, radio programs, university campuses, and via press releases to four local TV news stations (KSTP, WCCO, KARE11, KMSP). Nearly 50 research staff were hired and trained by the study’s principal investigator to assist with recruitment and study implementation. These staff members were recruited from various community settings, including universities in Minnesota, predominately African American professional organizations (e.g., Minnesota Black Nurses Association), local Federally Qualified Health Centers, gastroenterology centers, the Minnesota Department of Health, local hospitals, and the ACS. While at the State Fair, staff members wore a t-shirt with “Colon Cancer: iPrevent. iTreat. iBeat” printed on the front to recruit participants on site also.

Data collection

Prior to data collection, University of Minnesota’s institutional review board approved study protocol and informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants. Using the Internet-based survey research tool PsychData, a survey was administered via Apple iPads which consisted of a modified version of the MRN, knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions associated with CRCS survey developed by Rogers and Goodson (2014). Three questions were added measuring smoking status and CRCS intention. The survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete at the research site and after survey completion, participants had the choice to enter random drawings to win one of six incentives in the form of popular electronic devices. Participants could request access to preliminary results of the study (via relaxed dialogue at a local community center) if they furnished their e-mail address; participants were assured the address would not be linked to survey responses. Two months after data collection, the research team held a community event to release the preliminary findings and participants who provided their e-mails were invited. This event allowed the community to provide its interpretation of the results and recommendations for future research and advocacy efforts.

Upon survey completion, each participant received a consent form copy, along with an ACS brochure titled, “Get Tested” (focused on CRCS education). Each participant was also encouraged to walk through the Super Colon, an interactive educational tool. This large inflatable tool allowed participants to closely observe a model of healthy colon tissue, tissue with nonmalignant colorectal disease such as Crohn’s, colorectal polyps, and various stages of CRC. The participants and all other visitors were able to walk through the Super Colon to learn risks for developing CRC, symptoms, and treatment options, as well as the importance of CRCS and prevention strategies.

Measures

In this study, the authors used the Male Role Norms, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions associated with CRCS instrument developed previously by two members of the research team (Rogers & Goodson, 2014), but made two modifications. First, two questions were added regarding smoking status, because cigarette smoking is an established risk factor for CRC and 80% of African American smokers in Minnesota primarily smoke menthol cigarettes (American Lung Association, 2010; Carballo & Asman, 2011). These two questions were modified from the Measuring Tobacco Smoking Prevalence questions developed by the Global Adult Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group (2011). The two questions asked, “How often do you smoke tobacco?” and if the participant answered daily or less than daily, the authors asked, “Do you smoke menthol cigarettes?” Second, one survey question was added to measure CRCS intention and asked, “Do you plan to obtain CRCS in the future?” Participants were provided seven choices ranging from Yes, in the next 6 months to No, will not get screened.

Data Analyses

All analyses employed R v. 3.1.1 (R Core Team, 2013). The overall sample size for the survey was 297; however, sample sizes varied for different variables due to missing values. Alongside descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha was used as a measure of reliability/internal consistency for the MRN, knowledge, attitudes toward screening, perceived barriers to screening, and perceived subjective norms scales. In addition, interscale and interelement correlations were computed for these scales. Composite measures of all scales were created, and mean values were used in further analyses. CRCS intention was determined by combining answers from those who responded yes; and similarly, collapsing responses from those who indicated no in regard to obtaining CRCS in the future.

Within the MRN scale, seven subscales exist: Avoidance of Femininity, Dominance, Importance of Sex, Negativity Toward Sexual Minorities, Restrictive Emotionality, Self-Reliance Through Mechanical Skills, and Toughness. Thus, their scores were separately averaged to represent different aspects of MRN, along with an overall MRN score (and its mean). The utilization of these seven subfactors were appropriate as reliability coefficients for the 21 items were summed to create the MRN variable were reliable (MRN α = .90) and valid in a previous study conducted by members of the research team (Rogers & Goodson, 2014). While controlling for various demographic characteristics of the sample, a series of logistic regression models were run with intention as the predicted variable, to explore associations among the proposed constructs (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Samples of Items Used in the Survey of African American Men, to Assess Their Male Role norms, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions Associated With Colorectal Cancer Screening (CRCS) Intention.

| Item number in survey | Question | Demographic characteristics | Construct |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Role Norms | CRC and Screening Knowledge | Attitudes Toward CRC Screening | Perceived Subjective Norms | Perceived Barriers | |||

| 1 | What race do you self-identify as? | × | |||||

| 20 | Homosexuals should never marry. | × | |||||

| 41 | Colorectal cancer is a cancer of the colon or rectum. | × | |||||

| 62 | The thought of getting colorectal cancer scares me. | × | |||||

| 14 | Are you currently active/participating in any type of male dominant social group (e.g., fraternity, bowling league, Bible study group)? | × | |||||

| 13 | Do you have one doctor who you continually connect with (i.e., primary care/family physician)? | × | |||||

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 297 surveys met full inclusion criteria. Study participants had a mean age of 36.54 ± 13.24. Specifically, 123 (41%) were younger than age 30, 113 (38%) were 30 to 49 years old, and 61 (21%) were 50 to 65 years old. Nearly half were single (45%) and 78% had at least partially attended college. The majority of the participants worked a full-time (66%) or part-time (22%) job; the median household income per year was $35,000 to $49,999; and most had health insurance (87%). Regarding tobacco use, 22% of the participants smoked daily or less than daily, and nearly half of these smokers smoked menthol cigarettes (49%).

Most participants (78%) had visited a doctor in the past year, and 63% of the participants had a primary care physician whom they consulted regularly. Regarding cancer history, 71% did not have a family history of CRC and only one (0.34%)—who was well below the recommended screening age of 50 by the USPSTF—was ever diagnosed with CRC. One third (31%) of the sample had a family history of cancer. In terms of enrollment, most of the sample resided in Minneapolis (45%) or St. Paul (35%), Minnesota; nearly half of the sample (45%) was currently active in some form of male dominant social group (e.g., Bible study group, bowling league); 66% learned about the study via research study staff at the state fair, 5% via flyers, and 3% via friends. Additional participant demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant Demographic Characteristics.a

| Sample characteristics (N = 297) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18-22 | 51 | 17.2 |

| 23-29 | 72 | 24.2 |

| 30-39 | 53 | 17.9 |

| 40-49 | 60 | 20.2 |

| 50-65 | 61 | 20.1 |

| Current Minnesota residence | ||

| Minneapolis | 134 | 45.1 |

| St. Paul | 104 | 35.0 |

| Other | 59 | 19.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 134 | 45.1 |

| Unmarried in a relationship | 39 | 13.1 |

| Married | 109 | 36.7 |

| Divorced | 12 | 4.0 |

| Separated | 2 | 0.7 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.3 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Straight | 277 | 89.2 |

| Gay | 12 | 4.1 |

| I am struggling with my sexual orientation | 5 | 1.7 |

| Highest education level completed | ||

| Partial high school | 7 | 2.3 |

| GED or equivalent | 22 | 7.4 |

| High school diploma | 37 | 12.5 |

| Partial college (at least 1 year) | 64 | 21.6 |

| 2-Year college/associate degree | 36 | 12.2 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 78 | 26.4 |

| Master’s/advanced degree | 52 | 17.6 |

| Do you currently work? | ||

| No | 31 | 10.7 |

| Yes, part-time | 64 | 22.2 |

| Yes, full-time | 192 | 66.4 |

| Household income per year | ||

| <$15,000 | 42 | 14.5 |

| $15,000-$24,999 | 33 | 11.4 |

| $25,000-$34,999 | 33 | 11.4 |

| $35,000-$49,000 | 39 | 13.5 |

| $50,000-$74,000 | 55 | 19.0 |

| >$75,000 | 87 | 30.1 |

| Do you currently have health insurance? | ||

| Yes | 256 | 86.8 |

| No | 39 | 13.2 |

| Have you visited a doctor or other health care provider in the past 12 months? | ||

| Yes | 230 | 78.0 |

| No | 65 | 22.0 |

Information that does not add up to N = 297 is a result of data that were not reported.

Data Reliability and Validity

Cronbach’s alpha assessed whether scores for composite scales were internally consistent: 21 items were summed to create the MRN variable, 13 items in the knowledge scale, 7 items in the attitudes scale, 9 items in the perceived subjective norms scale, and 8 items in the perceived barriers scale. The lowest scoring scale was the knowledge index (α = .46). All other scales had reliability coefficients close to or above .80 (Attitudes: α = .79; Perceived Barriers: α = .86; and Perceived Subjective Norms: α = .89).

In light of sample size and item count, Ponterotto and Ruckdeschel (2007) recommend clustering scale lengths into three general ratings (e.g., moderate, good, and excellent) to consider the adequacy of magnitudes for coefficient alpha. Accordingly, coefficient alphas for the MRN subscales and total scale featured in Table 3 were evaluated as moderate (.75-.79), good (.80-.84), or excellent (.85 and up). With the exception of the moderate alpha observed for the Toughness subscale (.74), the other six MRN subscale alphas were good: Avoidance of Femininity (.80), Importance of Sex (.81), Dominance (.84), Restrictive Emotionality (.84), Self-Reliance Through Mechanical Skills (.85), and Negativity Toward Sexual Minorities (.87). The General Traditional Masculinity Ideology Factor (MRN total score) was excellent (.93).

Table 3.

Raw Score Means, Standard Deviations, and Cronbach’s Alphas for Male Role Norms (MRN).a

| Measure | M (SD) | N | α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Reliance Through Mechanical Skills | 4.42 (1.63) | 292 | .85 |

| Toughness | 3.98 (1.57) | 291 | .74 |

| Dominance | 2.31 (1.33) | 293 | .84 |

| Negativity Toward Sexual Minorities | 2.85 (1.68) | 293 | .87 |

| Importance of Sex | 3.35 (1.54) | 292 | .81 |

| Avoidance of Femininity | 3.18 (1.54) | 291 | .80 |

| Restrictive Emotionality | 2.54 (1.31) | 293 | .84 |

| MRN Total Score | 3.22 (1.14) | 294 | .93 |

MRN scores ranged from 1 to 7. Higher values indicate greater endorsement of traditional masculinity ideology.

To assess the underlying structure for the 21 items of the MRN scale, exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation was conducted. Results indicated seven factors were sufficient and mirrored the subscales originally proposed by its authors (Levant et al., 2013).

Male Role Norms

With response options on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), the level of disagreement/agreement for 21 items that made up the MRN was determined by combining those who disagreed and strongly disagreed, and similarly for those who responded strongly agree with those who responded agree. The statement with the highest percentage of participants disagreeing/strongly disagreeing was the President of the United States should always be a man (73%; Dominance subscale) followed by 67% who disagreed/strongly disagreed a man should never admit when others hurt his feelings. The highest percentage of agreement/strong agreement was for the statement men should have home improvement skills (45%) followed by 40% who agreed/strongly agreed men should be able to fix most things around the house. For each question in the MRN scale, the means ranged from 2.31 to 4.42. The sample (n = 294) had a total mean score of 3.22 (SD = 1.14), indicating the men, on average, slightly disagreed with endorsing a traditional masculinity ideology.

CRC and Screening Knowledge

Thirteen true/false statements formed the CRC and CRCS knowledge scale. The statements with the highest percentage of participants responding correctly were CRC is a cancer of the colon or rectum (96%—true statement) and CRC is a disease that affects only older, White men (96%—false statement), followed by the risk of developing CRC is greater as a person gets older (95%—true statement). Conversely, the highest percentage of incorrect response was for the true statement, a sigmoidoscopy is an appropriate test to screen for CRC (41%), followed by CRCS among average-risk men and women should begin at age 50 (41%), also a true statement. The participants varied in agreeing a colonoscopy (91%), FOBT (83%), and sigmoidoscopy (59%) are appropriate for testing though these three different screening tests are recommended for CRC. Yet 92% of the participants responded correctly to the true statement bleeding from the rectum, blood in your stool, or blood in the toilet after a bowel movement may be symptoms of CRC. The scores for the total sample (n = 294) on the knowledge scale items ranged from 15% to 100% with a mean score of 80.39% (SD = 15.69%). In order to receive a passing score (85% or better), participants were expected to answer 11 out of 13 questions correctly. Approximately one third of the study sample received a passing score (n = 97), where 11% received a perfect score of 100% (n = 32).

Attitudes Toward CRC and CRCS

Attitudes toward CRC and CRCS were measured by participants’ responses to seven survey items focused on CRC severity. The level of disagreement or agreement with these items, whose responses were scaled on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), was determined by combining those who disagreed and strongly disagreed and those who strongly agreed with those who agreed. The highest percentages of disagreement/strong disagreement were reported for the items, if I had CRC my career life would be over (68%) and I am afraid to even think about CRC (53%). Fifty-nine percent admitted the thought of getting CRC scares me, and half believed if I got CRC, my whole life would change. The mean score for the sample (n = 293) on the attitudes scale ranged from 2.19 to 3.54 for each question with a total mean score of 2.84 (SD = 0.76) for the composite scale.

Perceived Subjective Norms

Perceived subjective norms were measured by nine items on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly agree). Again, the level of disagreement or agreement was determined by combining those who responded strongly disagree with those who responded disagree, and similarly for those who agreed and strongly agreed. With the items measuring perceived subjective norms, the highest percentages of disagreement/strong disagreement were responses for it is important for me to comply with what my close friend believes in (26%) and for it is important for me to do what my parents think is appropriate (20%). The item, the important people in my life believe CRCS can help prevent CRC exhibited the highest proportion of agreement/strong agreement (64%). The mean scores for the sample (n = 294) on this factor ranged from 3.14 to 3.69 for each question with a total mean score of 3.44 (SD = 0.74) for the composite scale—meaning, overall, men in this study sample were rather uncertain regarding subjective norms.

Perceived Barriers

Responses to eight items focusing on screening barriers made up the perceived barriers scale and its responses lay on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The same dichotomous recoding of the responses was used for this scale. The highest percentages of disagreement/strong disagreement with items measuring perceived barriers were responses to having CRCS could take too much time (71%) and CRCS is embarrassing to me (63%). Twenty-six percent admitted I am afraid to find out there is something wrong when I have CRCS, and 25% marked I don’t know how to go about scheduling CRCS. The mean scores for the sample (n = 294) on this scale ranged from 2.10 to 2.56 for each question with a total mean score of 2.40 (SD = 0.77) for the composite variable.

Predictors of Intention to Screen for CRC

Of 286 study participants, 223 (78%) indicated they planned to obtain CRCS in the future. While controlling for various demographic characteristics of the sample, a series of logistic regression models were run with intention as the predicted variable to explore its association with MRN, knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Standardized Beta Coefficients for Predictors of Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Screening Intention, According to Logistic Regression Models.

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.507**** | 1.703**** | 1.702**** | 1.729**** | 1.861**** | 1.916**** |

| Zip: Other | 0.291 | 0.348 | 0.343 | 0.139 | 0.448 | 0.241 |

| Zip: St. Paul | 0.155 | 0.105 | 0.110 | 0.110 | 0.326 | 0.326 |

| Marital status: Married | 0.181 | −0.117 | −0.106 | −0.127 | −0.039 | −0.188 |

| Marital status: Separated | −0.955 | −1.513 | −1.500 | −1.406 | −1.652 | −1.880 |

| Sexual orientation: Straight | −0.333 | −0.257 | −0.255 | −0.233 | 0.011 | 0.057 |

| Medium education | 0.165 | 0.297 | 0.294 | 0.358 | −0.288 | −0.176 |

| High education | 0.534 | 0.515 | 0.507 | 0.516 | −0.121 | −0.231 |

| Low income | 0.297 | 0.328 | 0.335 | 0.347 | 0.911 | 0.887 |

| Medium income | 0.435 | 0.649 | 0.647 | 0.683 | 1.084 | 0.931 |

| Working: Yes | −0.672 | −0.804 | −0.802 | −0.767 | −1.030 | −1.161 |

| Health insurance: Yes | −0.402 | −0.281 | −0.278 | −0.216 | −0.190 | −0.128 |

| Religious: Other | −0.276 | −0.372 | −0.373 | −0.345 | −0.486 | −0.782 |

| UnsureCancer | −0.315 | −0.257 | −0.261 | −0.117 | −0.128 | 0.092 |

| SureCancer | 0.230 | 0.270 | 0.263 | 0.266 | 0.004 | −0.268 |

| UnsureCRC | 0.012 | −0.041 | −0.044 | −0.189 | −0.520 | −0.694 |

| SureCRC | −1.022 | −1.094 | −1.089 | −1.089 | −1.013 | −1.056 |

| Smoker | −0.241 | −0.321 | −0.323 | −0.416 | −0.402 | −0.351 |

| Male role norms | ||||||

| Dominance | −0.396 | −0.394 | −0.462 | −0.384 | −0.336 | |

| Self-Reliance | 0.379 | 0.376 | 0.362 | 0.078 | 0.101 | |

| Restrictive Emotionality | −0.076 | −0.074 | −0.016 | −0.056 | 0.032 | |

| Importance of Sex | 0.356 | 0.354 | 0.344 | 0.271 | 0.316 | |

| Toughness | −0.236 | −0.235 | −0.219 | −0.263 | −0.123 | |

| Avoidance of Feminity | −0.140 | −0.138 | −0.062 | −0.095 | −0.208 | |

| Knowledge | 0.022 | 0.059 | 0.009 | −0.033 | ||

| Attitudes | −0.222 | −0.591 | −0.307 | |||

| Perceived Subjective Norms | 1.269**** | 1.364**** | ||||

| Perceived Barriers | −0.853**** | |||||

p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. ****p < .0001.

Model 1

This model predicted whether participants intended to obtain CRCS based on their demographic characteristics. Demographic characteristics included the following variables: age, educational level, family history of cancer, marital status, residence, sexual orientation, and smoking status, among others. When demographic variables alone are considered, age (β = 1.507, χ2 = 28.119, p < .0001) is significantly (and positively) associated with intention to obtain CRCS.

Model 2

This model adds the seven factors MRN scale as separate predictors to the factors tested in Model 1. Age (β = 1.703, χ2 = 27.483, p < .0001) remained the only significant variable associated with intention to obtain screening for CRC. The strength of the association between age and intention was not altered by the other factors in the model.

Model 3

This model estimated participants’ CRCS intention as a function of their demographic characteristics, MRN broken down as seven factors, and knowledge. Once again, age (β = 1.702, χ2 = 27.423, p < .0001) maintained its role as the only significant predictor, among all factors.

Model 4

In this model, the role of attitudes, added to the prediction equation, along with demographic characteristics, MRN broken down as seven factors, and knowledge was examined. Once again, age (β = 1.729, χ2 = 27.855, p < .0001) maintained its role as the only significant predictor of CRCS intent, among all factors.

Model 5

In this model, the authors examined the role of perceived subjective norms, along with demographic characteristics, MRN broken down as seven factors, knowledge, and attitudes. Age (β = 1.861, χ2 = 25.696, p < .0001) and perceived subjective norms (β = 1.269, χ2 = 23.124, p < .0001) were significant predictors of CRCS intent probabilities. The positive regression coefficient for perceived subjective norms suggests the more social support a participant in this study’s sample has, the more likely he will get screened.

Model 6

In the final model, the role perceived barriers might play in participants’ CRCS intention was examined. A logistic regression was calculated to predict participants’ intention based on their demographic characteristics, MRN broken down as seven factors, knowledge, attitudes, and perceived barriers. This time, age (β = 1.916, χ2 = 21.732, p < .0001) and perceived barriers (β = −0.853, χ2 = 8.404, p = .0037) were significant. The negative regression coefficient associated with perceptions of barriers (i.e., agreeing/strongly agreeing there are several barriers to screening) indicated that the more barriers a participant in the sample perceived, the less likely he would obtain early detection screening for CRC.

Discussion

A conceptual model based on the TPB with MRN as an added theoretical construct was deployed to examine CRCS intentions of African American men, 18 to 65 years of age in Minnesota. Since a growing body of literature links masculinity or MRN to African American men’s health behavior, mortality, and health care use (Christy, Mosher, & Rawl, 2014; Hoyt, Stanton, Irwin, & Thomas, 2013), the research team hypothesized MRN influenced participants’ intentions to screen for CRC, independent of their attitudes, knowledge, and perceptions. In designing this study, the authors also anticipated these men lacked appropriate knowledge and espoused negative attitudes toward CRCS on the basis of findings from Rogers and Goodson (2014) and Brittain et al. (2012).

Although demographic characteristics (e.g., educational level, sexual orientation, and marital status) differed among the participants, the MRN factors did not make independent contributions to the regression models. Instead, the study’s findings indicated only three factors were significant among the models: age, perceived barriers, and perceived subjective norms.

Regarding age, more African American men in this study intended to receive CRCS as they got older. Since advancing age is associated with a rise in CRC incidence—increasing the need for CRCS, lack of knowledge regarding how CRC risk increases with age has been documented as a barrier to CRCS among older populations (Day, Walter, & Velayos, 2011). For example, in a qualitative study by Beeker, Kraft, Southwell, and Jorgensen (2000) involving 14 focus groups, researchers attempted to identify the range of behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs of older African American and white adults (≥50 years) that may be modifiable via targeted interventions. The discussions revealed only a few participants were aware CRC treatment is more effective if CRC is caught early and CRC risk increases with age. However, in the current study, 95% of the participants answered correctly the risk of developing CRC is greater as a person gets older.

Yet, contradicting previous national data, the recent study by Bailey et al. (2015) predicted a trend for increased CRC incidence in patients much younger than the recommended screening age of 50. Based on the predictive model, Bailey et al. (2015) developed from the retrospective cohort study of 393,241 patients (aged ≥20) with CRC from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, 20- to 34-year-olds’ CRC incidence rates was the highest and expected to upsurge by 38% and 90%, respectively, by 2020 and 2030. Since CRC is more treatable if detected earlier, the USPSTF should consider lowering the screening age for African Americans. Statewide insurance coverage of CRCS for African Americans ≥ age 45—an age change recommendation made by the American College of Gastroenterology 6 years ago—should earnestly be considered since treatment of CRC diagnosed in early stages costs approximately $3,000 less than treatment for advanced CRC (Luo, Bradley, Dahman, & Gardiner, 2009; Rex et al., 2009).

Conversely, as more perceived barriers arose for participants, the lower their intention was to complete CRCS. The current study’s findings are consistent with Rogers and Goodson (2014) who examined attitudes associated with CRCS among 157 young adult African Americans. Among this national sample of men aged 19 to 45 years, participants’ perceptions of barriers toward CRCS was significantly associated with more negative attitudes toward screening. Numerous studies have investigated perceptions of barriers (e.g., embarrassment, poor provider communication, and screening cost) of other underserved populations and corroborate these findings (Gbenga et al., 2005; Maxwell, Bastani, Crespi, Danao, & Cayetano, 2011). For instance, Jones, Devers, Kuzel, and Woolf (2010) conducted a two-part, mixed-methods study to identify patient-reported barriers to CRCS among 660 patients aged 50 to 75 years and 40 patients aged 45 to 75 years from family medicine practices in Virginia. With nearly 40% of the participants being African American, some leading barriers cited by study participants were fear, insurance and cost concerns, pain, and physician recommendation. Since the current screening status in the United States is only 6% higher (58.2%) than the 2008 baseline for Healthy People 2020 of 52.1% for persons aged 50 to 75 years, the research team agrees with Sabatino et al. (2015); more interventions are needed to overcome barriers among underserved populations to meet the Healthy People 2020 target of 70.5% for CRCS completion.

Similar to the current study’s findings regarding perceived subjective norms, a number of studies exist examining the noteworthy association between CRCS and social support among African American men. For instance, Cronan, Devos-Comby, Villalta, and Gallagher (2008) conducted a study of 158 low-income participants in southern California, ages 50 to 70, male (49%), and African American (85%). After utilizing survey research to assess ethnic disparities in CRCS rates among their sample and factors that could account for these differences, researchers learned that participants who were encouraged by their friends/family to obtain CRCS were more likely seek it. Furthermore, a descriptive, cross-sectional study by Brittain et al. (2012) reported social support was positively related to CRCS decision making among 64 African American men, aged 50 years and older. Accordingly, future research should consider developing and testing better measures of social support to influence development of more effective educational interventions.

Findings from this study are valuable for improving CRCS uptake among African American men. However, the study’s limitations should be considered. First, a convenience-sampling plan was utilized for this cross-sectional study, data were only collected in a state fair setting, and participation was limited to African American men living in Minnesota. Therefore, causation cannot be demonstrated and generalizing these findings to a larger population of African American men is not feasible. However, the fact that the research team recruited nearly 300 eligible African American male participants in such a short amount of time (7 days) suggests this population might view participation in health research activities more positively if the topic is pertinent to the African American community and researchers are perceived as trustworthy (Byrd et al., 2011; Katz et al., 2006).

Second, although self-report questionnaires are a common research methodology in behavioral science, both social desirability and nonresponse bias are potential concerns. Accordingly, the research team attempted to offset these concerns by testing the data’s reliability and validity, meticulously reviewing the data for “mechanisms of missingness” as recommended by Osborne (2013), and by securely collecting it online electronically—preventing survey alteration and eliminating transcription errors. Third, there were no men from other racial/ethnic groups in the study. The study purpose was not to compare racial groups, but to identify factors with the African American population. Furthermore, since Minnesota has a large African immigrant population including the largest Somali immigrant population in the United States, differences in CRCS rates between U.S.-born and first-generation immigrants should be taken into account. A recent report by MN Community Measurement (2016) documents only 24% of Somali immigrants have been screened for CRC in Minnesota, when compared with 71% of screening statewide. Limited research has also reported lower rates of cancer screening and preventive services among African immigrants (Sewali et al., 2015). Future research should explore barriers associated with CRCS disparities among African immigrants.

Last, an intrinsic limitation of behavioral research relates to the amount of measurement error embedded in analyses. Although the research team made efforts to minimize such error, testing the data revealed low internal consistency for the knowledge scale. The low Cronbach’s alpha for that scale (α = .46) may have influenced the construct behavior in the regression models that were tested. Conversely, the internal consistency score for the central construct assessed in this study, MRN, was quite high, allowing confidence in the findings that MRN do not appear to influence this sample’s CRCS intention.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this is one of the first studies to report correlates of CRCS intentions among African American men both older and younger than the USPSTF’s recommended age of 50. Furthermore, this study was the first to explore the value of a state fair setting for CRC-focused data collection and health promotion among African American men. Since a limited number of studies have reported on the use of giant inflatable, walk-through colon exhibits to reach underserved populations, future CRC-focused interventions should consider utilizing this educational tool (Briant et al., 2015; Redwood, Provost, Asay, Ferguson, & Muller, 2012; Sanchez, Palacios, Cole, & O’Connell, 2014). Furthermore, a number of men who entered the interactive colon exhibit, who were ineligible for the survey (i.e., ethnicities other than African American), expressed their appreciation for the exhibit and how they planned to obtain CRCS immediately. Also, it is important to note that one study participant was diagnosed at 22 years with Stage-IV CRC though he did not have a family history. Accordingly, since incidence rates are projected to rise among adults younger than age 50, challenging providers to recognize young-onset CRC in patients without known genetic predisposition should be seriously considered and studied further (Bailey et al., 2015).

Acknowledgments

The authors extend gratitude to the participants who made the study possible. The successful implementation of this study would not have been made possible without support from D-Brand Designs, Minnesota Gastroenterology, Q Health Connections, the Minnesota Cancer Alliance, and research team staff.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University of Minnesota or the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: the Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota, and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R25CA163184.

References

- Agrawal S., Bhupinderjit A., Bhutani M. S., Romero Y., Srinvasan R., Figueroa-Moseley C. (2005). Colorectal cancer in African Americans. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 100, 515-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. (2011). Minnesota Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. Retrieved from http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/hpcd/cdee/mcss/documents/mncancerfactsfigures2011033011.pdf

- American Cancer Society. (2014). Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2014-2016. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/documents/document/acspc-042280.pdf

- American Cancer Society. (2016). Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2016-2018. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-047403.pdf

- American Lung Association. (2010). Smoking rates among African Americans. Retrieved from http://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/about-smoking/facts-figures/african-americans-and-tobacco.html#12

- Bailey C. E., Hu C. Y., You Y. N., Bednarski B. K., Rodriquez-Bigas M. A., Skibber J. M., . . . Chang G. J. (2015). Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surgery, 150, 17-22. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeker C., Kraft J. M., Southwell B. G., Jorgensen C. M. (2000). Colorectal cancer screening in older men and women: Qualitative research findings and implications for intervention. Journal of Community Health, 25, 263-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briant K. J., Espinoza N., Galvan A., Carosso E., Marchello N., Linde S., . . . Thompson B. (2015). An innovative strategy to reach the underserved for colorectal cancer screening. Journal of Cancer Education, 30, 237-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain K., Loveland-Cherry C., Northouse L., Caldwell C. H., Taylor J. Y. (2012). Sociocultural differences and colorectal cancer screening among African American men and women. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, 100-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd G. S., Edwards C. L., Kelkar V. A., Phillips R. G., Byrd J. R., Pim-Pong D. S., . . . Pericak-Vance M. (2011). Recruiting intergenerational African American males for biomedical research studies: A major research challenge. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103, 480-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo R. S., Asman K. (2011). Epidemiology of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 9(Suppl. 1). doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-9-S1-S1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Cancer among men. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/data/men.htm

- Christy S. M., Mosher C. E., Rawl S. M. (2014). Integrating men’s health and masculinity theories to explain colorectal cancer screening behavior. American Journal of Men’s Health, 8, 54-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50, 1385-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan T. A., Devos-Comby L., Villalta I., Gallagher R. (2008). Ethnic differences in colorectal cancer screening. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 26, 63-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day L. W., Walter L. C., Velayos F. (2011). Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in the elderly patient. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 106(7), 1197-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gbenga O., Cassels A. N., Robinson C. M., DuHamel K., Tobin J. N., Sox C. H., Dietrich A. J. (2005). Perceptions of barriers and facilitators of cancer early detection among low-income minority women in community health centers. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97, 162-170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno García A. Z. (2012). Factors influencing colorectal cancer screening participation. Gastroenterology Research and Practice, 2012, 1-8. doi: 10.1155/2012/483417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Adult Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group. (2011). Tobacco questions for surveys: A subset of key questions from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/en_tfi_tqs.pdf

- Hoyt M. A., Stanton A. L., Irwin M. R., Thomas K. S. (2013). Cancer-related masculine threat, emotional approach coping, and physical functioning following treatment for prostate cancer. Health Psychology, 32, 66-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. M., Devers K. J., Kuzel A. J., Woolf S. H. (2010). Patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening: A mixed-methods analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38, 508-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz R. V., Kegeles S. S., Kressin N. R., Green B. L., Wang M. Q., James S. A., . . . Claudio C. (2006). The Tuskegee Legacy Project: Willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical research. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 17, 698-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant R. F., Hall R. J., Rankin T. J. (2013). Male Role Norms Inventory–Short Form (MRNI-SF): Development, confirmatory factor analytic investigation of structure, and measurement invariance across gender. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 228-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant R. F., Richmond K. (2007). A review of research on masculinity ideologies using the male role norms inventory. Journal of Men’s Studies, 15, 130-146. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Bradley C. J., Dahman B. A., Gardiner J. C. (2009). Colon cancer treatment costs for Medicare and dually eligible beneficiaries. Health Care Financing Review, 31(1), 35-50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell A. E., Bastani R., Crespi C. M., Danao L. L., Cayetano R. T. (2011). Behavioral mediators of colorectal cancer screening in a randomized controlled intervention trial. Preventive Medicine, 52, 167-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May F. P., Bromley E. G., Reid M. W., Baek M., Yoon J., Cohen E., . . . Spiegel B. M. (2014). Low uptake of colorectal cancer screening among African Americans in an integrated Veterans Affairs health care network. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 80, 291-298. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.01.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MN Community Measurement. (2016). 2015 Health equity of care report. Retrieved from http://mncm.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2015-Health-Equity-of-Care-Report-Final-2.11.2016.pdf

- Osborne J. W. (2013). Best practices in data cleaning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ponterotto J. G., Ruckdeschel D. E. (2007). An overview of coefficient alpha and a reliability matrix for estimating adequacy of internal consistency coefficients with psychological research measures. Perceptual & Motor Skills, 105, 997-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://www.r-project.org/

- Redwood D., Provost E., Asay E., Ferguson J., Muller J. (2012). Giant inflatable colon and community knowledge, intention, and social support for colorectal cancer screening. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10, 120192. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex D. K., Johnson D. A., Anderson J. C., Schoenfeld P. S., Burke C. A., Inadomi J. M. (2009). American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2008. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 104, 1739-1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rim S. H., Joseph D. A., Steele C. B., Thompson T. D., Seeff L. C. (2011). Colorectal cancer screening—United States, 2002, 2004, 2006, and 2008. MMWR Supplements, 60, 42-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. R., Goodson P. (2014). Male role norms, knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of colorectal cancer screening among young adult African American men. Frontiers in Public Health, 2, 1-12. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. R., Goodson P., Foster M. J. (2015). Factors associated with colorectal cancer screening among younger African American men: A systematic review. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 8(1), 133-156. Retrieved from http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/jhdrp/vol8/iss3/8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncancio A. M., Ward K. K., Fernandez M. E. (2013). Understanding cervical cancer screening intentions among Latinas using an expanded theory of planned behavior model. Behavioral Medicine, 39, 66-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino S. A., White M. C., Thomspon T. D., Klabunde C. N. (2015). Cancer screening test use: United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64, 464-468. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6417a4.htm?s_cid=mm6417a4_w [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez J. I., Palacios R., Cole A., O’Connell M. A. (2014). Evaluation of the walk-through inflatable colon as a colorectal cancer education tool: Results from a pre and post research design. BMC Cancer, 14, 626. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewali B., Pratt R., Abdiwahab E., Fahia S., Call K. T., Okuyemi K. S. (2015). Understanding cancer screening service utilization by Somali men in Minnesota. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17, 773-780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L., Jemal A., Ward E. M. (2009). Increase in incidence of colorectal cancer among young men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 18, 1695-1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. K., Simpson J. M., Trevena L. J., McCaffery K. J. (2014). Factors associated with informed decisions and participation in bowel cancer screening among adults with lower education and literacy. Medical Decision Making, 34, 756-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E. H., Pleck J. H. (1986). The structure of male role norms. American Behavioral Scientist, 29, 531-543. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2008). Guide to clinical preventive services, 2008: Recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (AHRQ Publication No. 08-05122). Rockville, MD: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Wade J. C. (2009). Traditional masculinity and African American men’s health-related attitudes and behaviors. American Journal of Men’s Health, 3, 165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade J. C., Rochlen A. B. (2013). Introduction: Masculinity, identity, and the health and well-being of African American men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14, 1-6. doi: 10.1037/a0029612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]