Abstract

Disclosure of HIV serostatus to sexual partners is mandated within certain states in the United States and other countries. Despite these laws implemented and public health efforts to increase disclosure, rates of disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV (PLWH) remain low, suggesting the need for interventions to assist PLWH with the disclosure process. We conducted a systematic review of studies testing whether HIV serostatus disclosure interventions increase disclosure to sexual partners. We searched six electronic databases and screened 484 records. Five studies published between 2005 and 2012 met inclusion criteria and were included in this review. Results showed that three of the HIV serostatus disclosure-related intervention studies were efficacious in promoting disclosure to sexual partners. Although all three studies were conducted in the United States the intervention content and measurements of disclosure across the studies varied, so broad conclusions are not possible. The findings suggest that more rigorous HIV serostatus disclosure-related intervention trials targeting different populations in the United States and abroad are needed to facilitate disclosure to sexual partners.

Introduction

Disclosing one’s HIV-positive serostatus can have benefits for both individuals infected with HIV and public health prevention efforts. For example, HIV serostatus disclosure can lead to social support, closeness in relationships, antiretroviral therapy initiation and adherence, psychological and physical wellbeing for people living with HIV (PLWH) [1-8]. From a public health perspective, disclosure of HIV serostatus is also vital because it allows sexual partners the opportunity to seek HIV testing and communicate about safer-sex practices, which can increase condom use and lead to an estimated 61 % reduction in the risk of HIV transmission [9-13]. Disclosure of HIV serostatus can also help with prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT), as HIV-positive pregnant women who disclose to their sexual partners have more assistance to successfully follow the PMTCT requirements [14-17]. However, there are a number of potential negative consequences such as HIV-related stigma, discrimination, blame, loss of economic support, abandonment, physical and emotional abuse, that make HIV serostatus disclosure unsafe, especially for women [4, 16, 18-20]. These negative consequences have served as barriers of HIV serostatus disclosure and led to behaviors that place uninfected sexual partners at risk for HIV transmission [21-23].

To date, most researchers have employed cross sectional survey methods to examine rates of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners and the factors associated with the process. Based on recent studies, rates of HIV sero-status disclosure to sexual partners range from 97 % in South Africa [24], 89 % in the United States [25], 86 % in Brazil [26] to 73 % in Canada [27], and 39 % in Haiti [28]. The characteristics contributing to low rates of disclosure to sexual partners in some regions of the world have been found to be related to shorter length of time since HIV diagnosis, HIV-related stigma, having multiple sexual partners, partners of HIV negative or unknown status, not receiving antiretroviral treatment, emotional distress, low disclosure self-efficacy, and unemployment due to HIV status [22, 28-33]. In an effort to further understand the reasons and approaches PLWH use to disclose or not disclose their HIV serostatus to sexual partners, a number of researchers have employed qualitative methods to explore the disclosure process among different groups including but not limited to adolescents, adult men and women, and men who have sex with men (MSMs) [19, 34-45].

For PLWH who have decided to disclose to a sexual partner, qualitative studies indicate that the most common motivators for disclosure are the risk of HIV infection and encouraging their sexual partner to test for HIV [36, 46]. Other qualitative research suggest that adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV who are deciding whether to disclose to their partners face barriers related to lack information and skills about how to disclose their HIV serostatus to sexual partners [47, 48]. Similarly, qualitative research conducted among women report that although they are aware of the benefits of disclosing their status to sexual partners, the fear of abandonment, violence and being blamed for bringing HIV to the family prevent them from sharing their status with their partners [49-52]. These findings are consistent for adult males and adolescents who do not disclose their HIV serostatus to sexual partners in fear of being stigmatized [48, 53-56].

Given the potential benefits of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners and the challenges PLWH face when deciding how, and when to disclose to sexual partners, it is clear that there is an ongoing need to support PLWH with the process. In order to improve rates of disclosure globally, it is necessary to examine the effectiveness of the existing interventions aimed at increasing disclosure to sexual partners. Although a number of reviews have been published on HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners, they have only examined characteristics related to disclosure and the process of disclosure as opposed to interventions developed to facilitate disclosure to sexual partners [16, 57, 58]. This paper aims to fill an important gap by providing a systematic review and synthesis of interventions designed to promote HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners.

Methods

Search Strategy

We searched the following databases for peer reviewed articles reporting on HIV/AIDS disclosure interventions for all types of individuals anywhere in the world: Pubmed, Embase, PsycInfo, PsycArticles, Academic Search Complete, and Global Health. Keywords for the search included HIV/AIDS; disclosure; serostatus; interventions; comparison; trials. All articles (n = 484) were initially screened by two reviewers who independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of studies to accept or reject for full text review. Abstracts were rejected if the studies did not have [1] interventions promoting HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners [2] an HIV disclosure outcome measure, and [3] an experimental or quasi-experimental study design. All studies yielded through the search terms described above were published before February 2014.

Full Text Review

The same two reviewers independently reviewed the full texts of the studies identified from the electronic search to determine if they were still eligible to undergo data extraction. In order to be included, studies had to evaluate an intervention designed to promote HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among any groups anywhere in the world. Data were extracted from eligible studies into an electronic spreadsheet. Reviewers discussed any disagreements in the data extracted, and referral to a third reviewer was done to resolve any disputes. We extracted the following data: study characteristics (authors, publication date, study sample, study location, type of study design, comparison group, outcome measures); and intervention characteristics (types of intervention strategies used and outcomes). We divided the interventions into two types: [1] group and peer-led approaches, and [2] online approaches.

Results

Inclusion and Exclusion of Studies

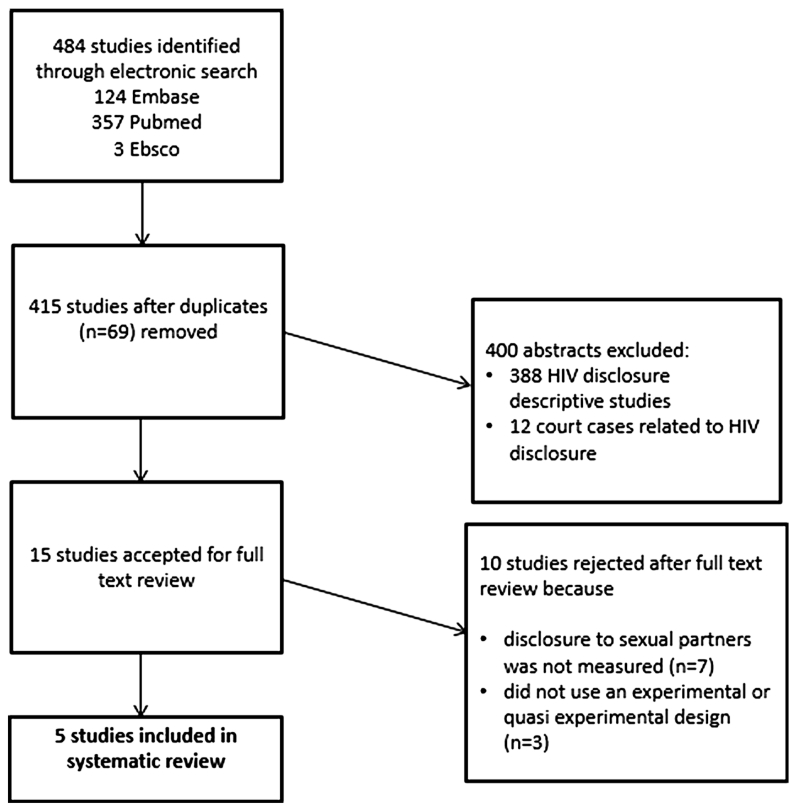

The electronic database searches retrieved 484 records (124 from Embase, 357 from Pubmed, and 3 from Ebsco). After removing the duplicates in RefWorks, 415 records were screened (Fig. 1). Of these, 388 were excluded because they were descriptive studies that only examined factors related to HIV serostatus disclosure but did not evaluate an intervention to promote HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners. Twelve records were excluded because they were court cases related to HIV disclosure. Fifteen records were selected at the abstract level for full text review because they described an intervention designed to promote HIV serostatus disclosure. Ten of the 15 studies that initially appeared to meet the inclusion criteria were later excluded after full text review. Seven of those reported on an HIV disclosure-related intervention but they did not include disclosure to a sexual partner as their outcome. Rather, outcomes for these studies were disclosure intention [59] disclosure efficacy and anxiety [60], disclosure to children [61, 62] or disclosure to any adults in their social network [63-65]. The remaining three studies were excluded because they did not use an experimental or quasi experimental design [66-68].

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of research study selection

Description of Included Studies

The final sample consisted of five studies published between 2005 and 2012, each of which evaluated an intervention designed to promote HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners (Table 1). The sample size for these studies ranged from 77 participants [69] to 1,631 participants [70]. There was little variation in study population across the five studies. The target group for nearly all of the intervention studies was MSM; only one study targeted a different population (minority women). Although the search was not limited to any geographical location, all of the studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review were conducted in the United States. Unlike the other three intervention studies that included only HIV-positive participants, Chiasson et al. 2009 and Hirsfield et al. 2012 recruited both HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals [70, 71].

Table 1.

Study and intervention characteristics of the five studies

| First author |

Sample characteristics |

Study design | Comparison/ control groups |

Intervention components | Assessment [compensation paid] |

Outcome variable | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group & peer-LED interventions | |||||||

| Serovich et al. 2009 [69] |

77 HIV- positive men who have sex with men in a Midwest, United States city |

Three arm randomized controlled trial |

Wait-list control (n = 21) |

Facilitator-only condition (n = 40), computer and facilitator condition (n = 37): four group sessions focusing on disclosure strategies, costs and benefits to disclosure, evaluation of different disclosure strategies |

Pre- & post-intervention, and 3 months follow- up. $40 for interview, $50 for focus group and $25 for at each data collecting point |

There was one thirteen item scale on discosure intention: “I intend to disclose when [specific sexual situation” and there was a separate thirteen item scale on disclosure behavior: “I disclosed when [specific sexual situation]” Respondents answered on a 5-point likert scale |

Disclosure mean scores: disclosure behavior at 3 months (2.11 IG vs. 2.83 CG, p < .05); disclosure intentions at 3 months (1.95 IG vs. 2.53 CG, p < .05) (lower scores indicate higher intention to disclose and intervention effect) |

| Teti et al. 2010 [72] |

184 HIV- positive women in Philadelphia, United States |

Two arm randomized controlled trial |

Comparison group (CG) (n = 92): brief messages from health care providers (HCPs) |

Intervention group (IG) (n = 92): received messages from HCPs, five weekly, 1.5 h group-level intervention, peer-led support groups focusing on safer sex, women's challenges and opportunities, HIV/AIDS and STI facts, condom use and negotiation, HIV status disclosure, problem solving, healthy relationships, and goal setting |

Pre-intervention, 6-,12-, and 18-months follow- ups [$10 gift cards, transportation tokens, and lunch] |

Participants were asked how many sexual partners they had disclosed to in the past six months and how many sexual partners they had had in the past six months and then a proportion was created (how many sexual partners one had disclosed to/how many sexual partners one had) |

Disclosure rates: disclosure at 6 months (83 % IG vs. 61 % CG, p < 0.05); 12 months (75 % IG vs. 68.6 % CG); 18 months (83.3 % IG vs. 60 % CG). After controlling for other variables, no statistically significant differences in disclosure were found between IG and CG at any time point |

| Wolitsky et al. 2005 [73] |

811 HIV- positive gay and bisexual men in New York, and San Francisco, United States |

Two arm randomized controlled trial |

Standard-of- care intervention (n = 398): 1.5–2 h single- session on safer sex |

Enhanced intervention (n = 413): six weekly, peer- led sessions focusing on relationships, HIV and STI transmission, drag and alcohol use, HIV status of sex partners, HIV status disclosure, and mental health |

Pre-intervention, 3 and 6-month follow ups [$5 travel reimbursements, food, gifts, $20 for 1st intervention session, and $10 for subsequent sessions] |

Participants were asked about disclosure with their main and their non-main sexual partners; there were two disclosure outcomes: [1] whether the participant reported having sex with someone without disclosing to them and [2] the proportion of individuals a participant had disclosed to before having sex (all, some, none) |

Disclosure rates: disclosure at 3 months (46.7 % IG vs. 42 % CG); 6 months (44.7 % IG vs. 42.9 % CG). Findings were not statistically significant |

| Online intervention | |||||||

| Chiasson et al. 2009 [71] |

522 HIV- positive men who have sex with men in United States |

One group pre-test post-test design |

Each participant served as his own control |

9 min dramatic HIV prevention video |

Pre-intervention and 3 months follow-up |

Participants responded to questions about their disclosure behavior using a five point likert scale dichotomized into two groups: yes (always, usually) and no (sometimes, rarely, never). Participants were asked whether they had partially (asked or told) or fully dislcosed (asked and told) to their last sexual partner at baseline and follow up |

Disclosure odds ratio (OR) at 3 months: partial (“telling”) disclosure (OR 2.10, 95 % CI 1.34, 3.36); full (“asking and telling”) disclosure(OR 3.37, 95 %Cl 1.22-5.95); partial (“asking”) disclosure (OR 2.79, 95 % CI1.73, 4.6) |

| Hirsfield et al. 2012 [70] |

1,631 HIV- positive men who have sex with men in United States |

Five arm randomized controlled trial |

Control condition (n = 609): received no intervention content |

Four conditions: (1) dramatic HIV prevention video; (2) documentary HIV prevention video; (3) both dramatic and documentary HIV prevention videos (n = 1, 874); (4) HIV prevention web page (n = 609) |

Pre-intervention and 60-days follow-up |

Participants were asked if there was partial or full disclosure to the last sexual partner they had had in the last 90 days. They defined partial disclosure as asking their sexual partner their status or telling a sexual partner their status and full disclosure as doing both |

Disclosure odds ratio (OR) at 2 months: partial (“telling”) disclosure (OR 0.95, 95 % CI 0.71, 1.27). Full (“asking and telling”) disclosure (OR1.32, 95 %CI 1.01, 1.74); partial (“asking”) disclosure (OR 1.51, 95 % CI 1.16, 1.98) |

IG intervention group

CG control group

Intervention Theoretical Framework and Design

All the studies selected for this review included a theory-based intervention to improve HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners. Serovich et al. 2009 employed the consequences theory of disclosure which purports that disclosure occurs once the rewards for disclosing outweigh associated costs [69]. Teti et al. 2010 used tenets of the Transtheoretical Model of the Stages of Change, the Modified AIDS Risk Reduction Model, and the Theory of Gender and Power [72]. Wolitsky et al. 2005 applied a number of behavioral theories including the Information-Motivation-Behavioral skills model of AIDS risk reduction, Social Cognitive Theory, and the Theory of Planned Behavior [73]. The online interventions (Chiasson et al. 2009; Hirshfield et al. 2012) were informed by developmental, social, and cognitive-constructivist learning theories [70,71].

Four studies used randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and one used a pretest/posttest single-arm design. There was variation in the number of study arms across the RCTs. Serovich et al. 2009 used a three-arm crossover design to compare a facilitator-only group session condition, a computer and facilitator condition, and a wait-list control condition [69]. Teti et al. 2010 used a two-arm design to compare a control group and a treatment group [72]. Wolitsky et al. 2005 used a two-arm design to compare an enhanced peer-led intervention to a one session standard-of-care [73]. Hirshfield et al. 2012 used a five-arm design and Chiasson et al. 2009 used a single group pre-test/posttest study [70, 71].

Intervention Content and Disclosure Measurement

Intervention contents varied from attending weekly support groups to viewing online videos. The pilot group support intervention for HIV-positive individuals by Serovich et al. 2009 was tested using a three-arm design (waitlist control, facilitator only, and computer and facilitator) and consisted of four weekly sessions without booster sessions [69]. Participants in the facilitator group completed all intervention activities face-to-face while participants in the computer-and-facilitator group completed initial assessment and paper-and-pencil exercises electronically and the remaining activities with a facilitator. The topics covered during the four sessions for each of the groups were related to strategies for disclosure, cost and benefits of disclosure, and evaluation of different disclosure strategies [69]. In the two-arm design study conducted by Teti et al. 2010, there were three components to the intervention [72]. In the first part, participants in the treatment group received prevention messages during their regularly scheduled clinic visits from healthcare professionals (nurses or physicians) who were trained in a 4-h training and quarterly booster sessions [72]. In the second part, participants attended five weekly 1.5 h group sessions to learn about safer sex, women’s challenges and opportunities, HIV/AIDS and STI facts, condom use and negotiation, HIV status disclosure, problem solving, healthy relationships, and goal setting. Participants who completed the second part of the intervention were eligible to attend 1-h weekly support group conducted by peer educators designed to help participants learn how to discuss condom use with their partners [72].

Wolitsky et al. 2005 evaluated a peer-led intervention for HIV-positive gay and bisexual men in a two-arm randomized study [73]. Participants in the treatment group attended six weekly 3-h sessions focusing on relationships, HIV and STI transmission, drug and alcohol use, HIV status of sex partners, HIV status disclosure, and mental health without booster sessions [73]. The two online interventions (Chiasson et al. 2009; Hirshfield et al. 2012) included HIV+ and HIV− individuals recruited from popular gay-oriented sexual networking websites [70, 71]. Chiasson et al. 2009 tested a nine-minute dramatic HIV prevention video in a one group pre-test post-test design [71]. Hirshfield et al. 2012 evaluated a five-arm intervention in which participants received the following conditions without a booster session: (1) dramatic video; (2) documentary video; (3) both dramatic and documentary videos; (4) prevention webpage; (5) control (no intervention content) [70]. The videos, and prevention webpage were designed to promote critical thinking about HIV disclosure, HIV testing, and condom use [70].

Disclosure was measured differently across the studies and disclosure was assessed between 2 and 18 months after implementation of the interventions. Serovich et al. 2009 used three 13-item scales to measure mean scores of disclosure behaviors to casual sex partners [69]. Teti et al. 2010 measured partner disclosure by dividing the number of partners to whom participants had disclosed by the number of partners they had in the past 6 months [72]. Wolitsky et al. 2005 assessed serostatus disclosure separately for new and existing partners and created a three category measure that measured whether participants disclosed to all, some, or none of their sex partners [73]. The two online interventions (Chiasson et al. 2009; Hirshfiled et al. 2012) measured partial (i.e. asking or telling) and full (i.e. both asking and telling) disclosure [70, 71].

Summary of Study Findings

Intervention impact was mixed across the studies. Serovich et al. 2009 found a positive effect on disclosure behavior scores at 3 months follow-up for the facilitator-only group [69]. However, there was no effect in the computer and facilitator group in comparison to the wait-list control. Teti et al. 2010 reported an increase in disclosure at 6-, 12-, and 18-months follow-up but these disclosure rates never reached a statistically significant difference [72]. Similarly, Wolitsky et al. 2005 reported that no significant differences were found between the intervention condition and the control group in the proportion of sex partners disclosed to or in the percentage of men reporting sex with a new sex partner who was unaware of the participant’s HIV status at 3-, and 6-months follow-up [73]. The online interventions showed a positive effect at 3-months follow-up for the pre-test posttest single group design [71], and 2-months follow-up for the randomized controlled trial, showing participants who received the pooled dramatic and documentary intervention more likely to report partial (“asking”) and full disclosure (“asking and telling”) than those in the control group [70].

Discussion

The objective of this paper was to conduct a systematic review of interventions designed to promote HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among PLWH. Our findings revealed that only a small number of studies have evaluated an intervention aiming to increase disclosure to sexual partners. Furthermore, the five intervention studies included in this review had other primary outcome measures such as HIV testing, and condom use, indicating that interventions focusing strictly on HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners are needed. The five HIV serostatus disclosure-related intervention studies were all conducted in the United States and the target group for nearly all of the intervention studies were MSM; only one study reviewed targeted a different population (and their focus was minority women). The findings of the interventions were mixed, with three (Serovich et al. 2009; Chiasson et al. 2009; Hirsfield et al. 2012) out of the five studies showing that participating in a disclosure-related intervention program significantly increased disclosure to sexual partners among MSMs [69-71]. Although three of the interventions were efficacious in promoting HIV serostatus, their findings must be interpreted with caution.

There was considerable variation in intervention content across the three efficacious interventions. Specifically, the first intervention (Serovich et al. 2009) consisted of four weekly support groups session using an RCT three-arm design, comparing a facilitator-only group session condition, a computer and facilitator condition, and a wait-list control whereas the other two interventions (Chiasson et al. 2009; Hirshfield et al. 2012) consisted of online delivered interventions using a single-arm and five-arm design to compare groups that viewed a dramatic HIV prevention video, documentary HIV prevention video, both the dramatic and documentary HIV prevention videos, HIV prevention web page, and a control group that received no intervention content [69-71]. Although there was a positive effect in the first intervention (Serovich et al. 2009) on disclosure to casual sexual partners among MSMs in the facilitator-only group, the computer-and-facilitator group was not statistically different from the control group [69]. One explanation offered for this finding is the preference of the participant to meet face to face with someone and verbally discuss their obstacles in the facilitator-only group.

Both of the interventions (Chiasson et al. 2009; Hirshfield et al. 20102) delivered online were efficacious at increasing HIV serostatus disclosure [70, 71]. However, it must be noted that perhaps the reason the online studies found a significant increase in disclosure was because the majority of the participants were HIV-negative. For example, of the 522 men who completed the first online intervention (Chiasson et al. 2009), only 72 were HIV-positive and in the other online intervention (Hirsfield et al. 2009) only 532 out of 3,092 respondents were HIV-positive. Since the barriers to HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners that PLWH face are different from HIV uninfected individuals, future intervention studies promoting HIV serostatus disclosure online should target HIV-positive participants.

The findings of the remaining two disclosure-related interventions (Wolitsky et al. 2005; Teti et al. 20120) were non-significant [72, 73]. It is possible that these non-significant findings were due to the content of the interventions themselves. On the other hand, researchers identified other potential issues that may have contributed to the non-significant findings. Some of the reasons Teti et al. 2010 reported for the lack of significance were reduced sample size due to attrition and the manner in which disclosure was measured [72]. An additional reason potentially limiting the effect of the interventions was the fact that the interventions had multiple goals such as decreasing sexual partners, and unprotected intercourse as opposed to focusing solely on promoting HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners [72, 73]. Regarding the study focusing on minority women, Teti et al. 2010 suggest the findings were non-significant due to the fact that the intervention did not remove or sufficiently address the risks associated with women’s HIV serostatus disclosure such as abandonment, stigma, discrimination, and violence [72].

More research and standardized interventions are needed to promote disclosure to sexual partners. Among the disclosure-related intervention studies included in this review, there was significant variation across the studies in terms of setting, sampling, study design, definition of outcome and intervention content. The small numbers of studies included in the review, combined with variation across these studies, prevent us from making broad conclusions about the efficacy of existing interventions focusing on promoting disclosure to sexual partners. Rather, they point to a pressing need for additional research on how to promote disclosure among a much broader range of populations and settings.

First, the fact that only five interventions were included and they were all conducted in the United States indicates the urgent need to implement and evaluate more disclosure-related interventions focusing on sexual partners. Regarding the small number of included studies in this review it is plausible that there are more interventions that have been implemented to promote HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners but they have not been quantitatively evaluated and published in a peer review journal. For example, Maiorana et al. 2012 describes qualitative findings of patients’ response regarding disclosure messages they received as part of a number of prevention with positives interventions conducted in clinical settings throughout the United States but does not offer quantitative findings regarding disclosure rates to sexual partners among the participants [74]. Similarly, interventions related to HIV serostatus disclosure have been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (Kaaya et al. 2013; Mundell et al. 2011), however, they were excluded from our systematic review because they did not measure disclosure rates to sexual partners. Two of the disclosure-related intervention studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa were excluded from the current review because they only measured disclosure to anyone within the participants’ social networks [63, 64]. While disclosure to broader networks is an important goal for the psychosocial well-being of PLWH, disclosure to sexual partners is crucial for initiating communications about safe sex. In addition, two other interventions focusing on disclosure to sexual partners in sub-Saharan Africa did not meet our inclusion criteria due to weak study designs [59, 66]. Given the potential of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners to prevent new HIV infections, there is a dire need to develop, implement, and evaluate rigorous disclosure-related intervention studies in areas with high HIV prevalence.

Second, although the studies included in this review were conducted in the United States they do not represent all groups and regions. For example, the included studies focused mostly on MSMs, with the exception of one study that included minority women. Future research and interventions regarding disclosure to sexual partners in the United States and other developed countries should target different population groups such as immigrants and ethnic minorities [1, 6, 75, 76]. Communication within sexual partnerships may differ across these different sub-populations, and interventions may need to be tailored accordingly. Third, future research should discern whether there are differences in patterns of disclosure across high and low prevalence settings or differences in patterns of disclosure across different sub-populations. For example, it is possible that pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa face different barriers to disclosing their status than pregnant women in the United States. Understanding these differences may contribute to the development of intervention tailored specifically to the context and population at hand.

In the ongoing fight against the spread of HIV, there continues to be a pressing need for interventions that successfully support individuals through the process of disclosing their HIV serostatus to their sexual partner. Nonetheless, it is critical to remember that there will always be individuals and populations for which disclosure is not a safe or recommended behavior. As such, it is imperative that disclosure-related researchers and interventionists continuously monitor the potential risks and outcomes of disclosure so that HIV-positive individuals confer the benefits of disclosure without experiencing harm during the process.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (T32 AI007001).

Contributor Information

Donaldson F. Conserve, Department of Health Behavior, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27509, USA

Allison K. Groves, Department of Sociology, Center on Health, Risk and Society, American University, Washington, DC, USA

Suzanne Maman, Department of Health Behavior, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27509, USA.

References

- 1.Stutterheim SE, Shiripinda I, Bos AE, Pryor JB, de Bruin M, Nellen JF, et al. HIV status disclosure among HIV-positive African and Afro-Caribbean people in the Netherlands. AIDS Care. 2011;23(2):195–205. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.498873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klitzman R, Kirshenbaum S, Dodge B, Remien R, Ehrhardt A, Johnson M, et al. Intricacies and inter-relationships between HIV disclosure and HAART: a qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2004;16(5):628–40. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001716423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stirratt MJ, Remien RH, Smith A, Copeland OQ, Dolezal C, Krieger D. The role of HIV serostatus disclosure in antiretroviral medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(5):483–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parsons JT, VanOra J, Missildine W, Purcell DW, Gómez CA. Positive and negative consequences of HIV disclosure among seropositive injection drug users. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16(5):459–75. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.5.459.48741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simoni JM, Demas P, Mason HR, Drossman JA, Davis ML. HIV disclosure among women of African descent: associations with coping, social support, and psychological adaptation. AIDS Behav. 2000;4(2):147–58. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conserve DF, King G. An examination of the HIV serostatus disclosure process among Haitian immigrants in New York City. AIDS Care. 2014;26(10):1270–4. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.902422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson BL. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1266–75. doi: 10.1080/09540120801926977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skhosana NL, Struthers H, Gray GE, McIntyre JA. HIV disclosure and other factors that impact on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: the case of Soweto, South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2006;5(1):17–26. doi: 10.2989/16085900609490363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anglewicz P, Chintsanya J. Disclosure of HIV status between spouses in rural Malawi. AIDS Care. 2011;23(8):998–1005. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.542130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hightow-Weidman LB, Phillips G, II, Outlaw AY, Wohl AR, Fields S, Hildalgo J, et al. Patterns of HIV disclosure and condom use among HIV-infected young racial/ethnic minority men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):360–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maman S, Mbwambo JK, Hogan NM, Weiss E, Kilonzo GP, Sweat MD. High rates and positive outcomes of HIV-serostatus disclosure to sexual partners: reasons for cautious optimism from a voluntary counseling and testing clinic in Dar es Salaam. Tanzania AIDS Behavior. 2003;7(4):373–82. doi: 10.1023/b:aibe.0000004729.89102.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crepaz N, Marks G. Serostatus disclosure, sexual communication and safer sex in HIV-positive men. AIDS Care. 2003;15(3):379–87. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000105432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connell AA, Reed SJ, Serovich JA. The efficacy of serostatus disclosure for HIV transmission risk reduction. AIDS Behav. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0848-2. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0848-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madiba S, Letsoalo R. HIV disclosure to partners and family among women enrolled in prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV program: implications for infant feeding in poor resourced communities in South Africa. Global J Health Sci. 2013;5(4):p1. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n4p1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Awiti Ujiji O, Ekström AM, Ilako F, Indalo D, Wamalwa D, Rubenson B. Reasoning and deciding PMTCT-adherence during pregnancy among women living with HIV in Kenya. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(7):829–40. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.583682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(4):299–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Msuya S, Mbizvo E, Hussain A, Uriyo J, Sam N. Stray-Pedersen B. Low male partner participation in antenatal HIV counselling and testing in northern Tanzania: implications for preventive programs. AIDS Care. 2008;20(6):700–9. doi: 10.1080/09540120701687059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gielen AC, Fogarty L, O’Campo P, Anderson J, Keller MJ, Faden R. Women living with HIV: disclosure, violence, and social support. J Urban Health. 2000;77(3):480–91. doi: 10.1007/BF02386755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bird JD, Voisin DR. “You’re an Open Target to Be Abused”: a qualitative study of stigma and HIV self-disclosure among black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2193–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrak JA, Doyle AM, Smith A, Skinner C, Hedge B. Factors associated with self-disclosure of HIV serostatus to significant others. Br J Health Psychol. 2001;6(1):69–79. doi: 10.1348/135910701169061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciccarone DH, Kanouse DE, Collins RL, Miu A, Chen JL, Morton SC, et al. Sex without disclosure of positive HIV sero-status in a US probability sample of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):949–54. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners and sexual risk behaviours among HIV-positive men and women, Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Trans Infect. 2007;83(1):29–34. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel K, Lekas H-M, Schrimshaw EW. Serostatus disclosure to sexual partners by HIV-infected women before and after the advent of HAART. Women Health. 2005;41(4):63–85. doi: 10.1300/J013v41n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longinetti E, Santacatterina M, El-Khatib Z. Gender perspective of risk factors associated with disclosure of HIV status, a cross-sectional study in Soweto, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e95440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Przybyla S, Golin C, Widman L, Grodensky C, Earp JA, Suchindran C. Examining the role of serostatus disclosure on unprotected sex among people living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28(12):677–84. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee L, Bastos FI, Bertoni N, Malta M, Kerrigan D. The role of HIV serostatus disclosure on sexual risk behaviours among people living with HIV in steady partnerships in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Global Public Health. 2014;9(9):1093–106. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.952655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen AH, Forrest JI, Kanters S, O’Brien N, Salters KA, McCandless L, et al. Factors associated with disclosure of HIV status among a cohort of individuals on antiretroviral therapy in British Columbia Canada. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(6):1014–26. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0623-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conserve DF, King G, Dévieux JG, Jean-Gilles M, Malow R. Determinants of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partner among HIV-positive alcohol users in Haiti. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(6):1037–45. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0685-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vu L, Andrinopoulos K, Mathews C, Chopra M, Kendall C, Eisele TP. Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners among HIV-infected men and women in Cape Town South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):132–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9873-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Overstreet NM, Earnshaw VA, Kalichman SC, Quinn DM. Internalized stigma and HIV status disclosure among HIV-positive black men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2013;25(4):466–71. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.720362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Przybyla SM, Golin CE, Widman L, Grodensky CA, Earp JA, Suchindran C. Serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV: examining the roles of partner characteristics and stigma. AIDS Care. 2013;25(5):566–72. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.722601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lunze K, Cheng DM, Quinn E, Krupitsky E, Raj A, Walley AY, et al. Nondisclosure of HIV infection to sex partners and alcohol’s role: a Russian experience. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):390–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0216-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalichman SC, Nachimson D. Self-efficacy and disclosure of HIV-positive serostatus to sex partners. Health Psychol. 1999;18(3):281. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walcott MM, Hatcher AM, Kwena Z, Turan JM. Facilitating HIV status disclosure for pregnant women and partners in rural Kenya: a qualitative study. BMC public Health. 2013;13(1):1115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnold EA, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. ‘Triply cursed’: racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young black gay men. Cult Health Sex. 2014;16(6):710–22. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.905706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maman S, van Rooyen H, Groves AK. HIV status disclosure to families for social support in South Africa (NIMH Project Accept/HPTN 043) AIDS Care. 2014;26(2):226–32. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.819400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clum GA, Czaplicki L, Andrinopoulos K, Muessig K, Hamvas L, Ellen, et al. Strategies and outcomes of HIV status disclosure in HIV-positive young women with abuse histories. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(3):191–200. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Psaros C, Barinas J, Robbins GK, Bedoya CA, Safren SA, Park ER. Intimacy and sexual decision making: exploring the perspective of HIV positive women over 50. AIDS patient care STDs. 2012;26(12):755–60. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sobo E. Human immunodeficiency virus seropositivity self-disclosure to sexual partners: a qualitative study. Holist Nurs Pract. 1995;10(1):18–28. doi: 10.1097/00004650-199510000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Serovich JM, Oliver DG, Smith SA, Mason TL. Methods of HIV disclosure by men who have sex with men to casual sexual partners. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2005;19(12):823–32. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Relf MV, Bishop TL, Lachat MF, Schiavone DB, Pawlowski L, Bialko MF, et al. A qualitative analysis of partner selection, HIV serostatus disclosure, and sexual behaviors among HIV-positive urban men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(3):280–97. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michaud P-A, Suris J-C, Thomas LR, Kahlert C, Rudin C, Cheseaux J-J. To say or not to say: a qualitative study on the disclosure of their condition by human immunodeficiency virus–positive adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(4):356–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.King R, Katuntu D, Lifshay J, Packel L, Batamwita R, Nakayiwa S, et al. Processes and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(2):232–43. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klitzman RL. Self-disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners: a qualitative study of issues faced by gay men. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc. 1999;3(2):39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maman S, Cathcart R, Burkhardt G, Omba S, Behets F. The role of religion in HIV-positive women’s disclosure experiences and coping strategies in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(5):965–70. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sowell RL, Seals BF, Phillips KD, Julious CH. Disclosure of HIV infection: how do women decide to tell? Health Educ Res. 2003;18(1):32–44. doi: 10.1093/her/18.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Busza J, Besana GV, Mapunda P, Oliveras E. “I have grown up controlling myself a lot”. Fear and misconceptions about sex among adolescents vertically-infected with HIV in Tanzania. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21(41):87–96. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41689-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Nuil JI, Mutwa P, Asiimwe-Kateera B, Kestelyn E, Vyankandondera J, Pool R, et al. “Let’s Talk about Sex”: a qualitative study of Rwandan adolescents’ views on sex and HIV. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e102933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shikwane ME, Villar-Loubet OM, Weiss SM, Peltzer K, Jones DL. HIV knowledge, disclosure and sexual risk among pregnant women and their partners in rural South Africa. SAHARA-J. 2013;10(2):105–12. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2013.870696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crankshaw TL, Mindry D, Munthree C, Letsoalo T, Maharaj P. Challenges with couples, serodiscordance and HIV disclosure: healthcare provider perspectives on delivering safer conception services for HIV-affected couples, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):1–7. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colombini M, Mutemwa R, Kivunaga J, Moore LS, Mayhew SH. Experiences of stigma among women living with HIV attending sexual and reproductive health services in Kenya: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):412. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rujumba J, Neema S, Byamugisha R, Tylleskär T, Tumwine JK, Heggenhougen HK. “Telling my husband I have HIV is too heavy to come out of my mouth”: pregnant women’s disclosure experiences and support needs following antenatal HIV testing in eastern Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(2):1–10. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaskins SW. Disclosure decisions of rural African American men living with HIV disease. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2006;17(6):38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paiva V, Segurado AC, Filipe EMV. Self-disclosure of HIV diagnosis to sexual partners by heterosexual and bisexual men: a challenge for HIV/AIDS care and prevention. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2011;27(9):1699–710. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2011000900004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mburu G, Hodgson I, Kalibala S, Haamujompa C, Cataldo F, Lowenthal ED, et al. Adolescent HIV disclosure in Zambia: barriers, facilitators and outcomes. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fair C, Albright J. “Don’t tell him you have HIV unless he’s ‘the one’”: romantic relationships among adolescents and young adults with perinatal HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(12):746–54. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mayfield Arnold E, Rice E, Flannery D, Rotheram-Borus M. HIV disclosure among adults living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2008;20(1):80–92. doi: 10.1080/09540120701449138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sullivan KM. Male self-disclosure of HIV-positive serostatus to sex partners: a review of the literature. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2005;16(6):33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olley B. Improving well-being through psycho-education among voluntary counseling and testing seekers in Nigeria: a controlled outcome study. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):1025–31. doi: 10.1080/09540120600568756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greene K, Carpenter A, Catona D, Magsamen-Conrad K. The Brief Disclosure Intervention (BDI): facilitating African Americans’ disclosure of HIV. J Commun. 2013;63(1):138–58. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murphy DA, Armistead L, Marelich WD, Payne DL, Herbeck DM. Pilot trial of a disclosure intervention for HIV? mothers: the TRACK program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(2):203. doi: 10.1037/a0022896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nicastro E, Continisio GI, Storace C, Bruzzese E, Mango C, Liguoro I, et al. Family group psychotherapy to support the disclosure of HIV status to children and adolescents. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27:363–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaaya SF, Blander J, Antelman G, Cyprian F, Emmons KM, Matsumoto K, et al. Randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of an interactive group counseling intervention for HIV-positive women on prenatal depression and disclosure of HIV status. AIDS Care. 2013;25(7):854–62. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.763891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mundell JP, Visser MJ, Makin JD, Kershaw TS, Forsyth BW, Jeffery B, et al. The impact of structured support groups for pregnant South African women recently diagnosed HIV positive. Women Health. 2011;51(6):546–65. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.606356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Serovich JM, Reed SJ, Grafsky EL, Hartwell EE, Andrist DW. An intervention to assist men who have sex with men disclose their serostatus to family members: results from a pilot study. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1647–53. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9905-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kairania R, Gray RH, Kiwanuka N, Makumbi F, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, et al. Disclosure of HIV results among discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda: a facilitated couple counselling approach. AIDS Care. 2010;22(9):1041–51. doi: 10.1080/09540121003602226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Semrau K, Kuhn L, Vwalika C, Kasonde P, Sinkala M, Kankasa C, et al. Women in couples antenatal HIV counseling and testing are not more likely to report adverse social events. AIDS. 2005;19(6):603. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000163937.07026.a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Rosa CJ, Marks G. Preventive counseling of HIV-positive men and self-disclosure of serostatus to sex partners: new opportunities for prevention. Health Psychol. 1998;17(3):224. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Serovich JM, Reed S, Grafsky EL, Andrist D. An intervention to assist men who have sex with men disclose their serostatus to casual sex partners: results from a pilot study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(3):207. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hirshfield S, Chiasson MA, Joseph H, Scheinmann R, Johnson WD, Remien RH, et al. An online randomized controlled trial evaluating HIV prevention digital media interventions for men who have sex with men. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e46252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chiasson MA, Shaw FS, Humberstone M, Hirshfield S, Hartel D. Increased HIV disclosure three months after an online video intervention for men who have sex with men (MSM) AIDS Care. 2009;21(9):1081–9. doi: 10.1080/09540120902730013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Teti M, Bowleg L, Cole R, Lloyd L, Rubinstein S, Spencer S, et al. A mixed methods evaluation of the effect of the protect and respect intervention on the condom use and disclosure practices of women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):567–79. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wolitski RJ, Gómez CA, Parsons JT. Effects of a peer-led behavioral intervention to reduce HIV transmission and promote serostatus disclosure among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 2005;19:S99–109. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167356.94664.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maiorana A, Koester KA, Myers JJ, Lloyd KC, Shade SB, Dawson-Rose C, et al. Helping patients talk about HIV: inclusion of messages on disclosure in prevention with positives interventions in clinical settings. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(2):179–92. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nellen JF, Sprangers MA, Prins JM, Nieuwkerk PT, Sumari-de Boer IM. Personalized stigma and disclosure concerns among HIV-infected immigrant and indigenous HIV-infected persons in the Netherlands. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv. 2012;11(1):42–56. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chin D, Kroesen KW. Disclosure of HIV infection among Asian/Pacific Islander American women: cultural stigma and support. Cult Diversity Ethnic Minor Psychol. 1999;5(3):222. [Google Scholar]