Abstract

Background

Multimodality treatment improves the chance of survival but increases the risk for long-term side effects in young cancer survivors, so-called” Adolescents and Young Adults“(AYAs). Compared to the general population AYAs have a 5 to 15-fold increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity. Thus, improving modifiable lifestyle risk factors is of particular importance.

Methods

The INAYA trial included AYAs between 18 and 39 years receiving an intensified individual nutrition counseling at four time points in a 3-month period based on a 3-day dietary record. At week 0 and 12 AYAs got a face-to-face counseling, at week 2 and 6 by telephone. Primary endpoint was change in nutritional behavior measured by Healthy Eating Index - European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (HEI-EPIC).

Results

Twenty-three AYAs (11 female, 12 male, median age 20 years (range 19–23 years), median BMI: 21.4 kg/m2 (range: 19.7–23.9 kg/m2) after completion of cancer treatment for sarcoma (n = 2), carcinoma (n = 2), blastoma (n = 1), hodgkin lymphoma (n = 12), or leukemia (n = 6) were included (median time between diagnosis and study inclusion was 44 month).

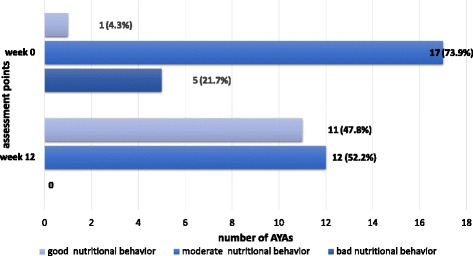

The primary endpoint was met, with an improvement of 20 points in HEI-EPIC score in 52.2 % (n = 12) of AYAs. At baseline, median HEI-EPIC score was 47.0 points (range from 40.0 to 55.0 points) and a good, moderate and bad nutritional intake was seen in 4.3, 73.9 and 21.7 % of AYAs. At week 12, median HEI-EPIC improved significantly to 65.0 points (range from 55.0 to 76.0 points) (p ≤ 0.001) and a good, moderate and bad nutritional intake was seen in 47.8, 52.2 and 0 % of AYAs. No change was seen in quality of life, waist-hip ratio and blood pressure.

Conclusion

Intensified nutrition counseling is feasible and seem to improve nutritional behavior of AYAs. Further studies will be required to demonstrate long-term sustainability and confirm the results in a randomized design in larger cohorts.

Trial registration

Clinical trial identifier DRKS00009883 on DRKS

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2896-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Background

Multimodality treatment, combining systemic and local therapies, offer an increasing number of patients the chance long-term survival or even cure. Currently, the number of cancer survivors is estimated to be about 15 million in the US rising to about 20 million within the next decade [1].

While improving treatment results and outcome on the one side, multimodality treatment may also increase the risk for physiological, psychological and social long-term sequelae on the other side. Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) receiving their cancer treatment during childhood are at particular risk for long-term side effects. According to the Childhood Cancer Survivor study (CCSS, n = 10,397) 2 out of 3 AYAs have treatment related long-term toxicities [2].

The major long-term toxicities and cause of mortality after treatment of childhood cancer are cardiovascular diseases like cardiomyopathy, chronic heart failure (CHF) and valvular problems [3]. Compared to general population AYAs have a 5 to 15-fold increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity [3–5]. The individual risk is determined by treatment related factors (e.g. type of chemotherapeutic agents, application schedule, number of cycles, cumulative dose of different agents, and combination with radiotherapy) and non-treatment related factors (nicotine abuse, diabetes mellitus, dyslipoproteinemia and hypertension [6]. AYAs who have received anthracycline-based treatment combined with chest radiation possess the highest risk for cardiovascular late toxicity, which may further be enhanced by non-treatment related factors [6].

Whereas large clinical trials are conducted to improve patient outcome, both in terms of cure rates and reduction of long-term toxicities, prospective studies evaluating modifications of lifestyle factors as potential non-treatment related risk factors for long-term toxicity in AYAs are lacking.

In adult survivors of breast and prostate cancer some studies have demonstrated that physical activity and healthy eating can increase survival [7, 8].

The WHEL study showed that telephone nutrition counseling can achieve major increases in the intake of micronutrient- and phytochemical-rich vegetables, fruit and fiber in breast cancer survivors [9]. The ENRGY trial has shown that a behavioral weight loss intervention can lead to clinically meaningful weight loss in overweight/obese breast cancer survivors [10]. However, with a median age at diagnosis of more than 60 years for these cancer survivors, the psychosocial background and living conditions largely differ from AYAs. Little is known about the feasibility and the effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in an AYA population at risk for cardiovascular disease.

Furthermore, only 10 % of the cancer survivors are following a healthy lifestyle without any additional intervention [11]. A large number of cancer survivors are overweight (58 %), eat less than 5 times per day fruits and vegetables (82 %) and perform no sport activities (55 %) [11].

The correlation between nutrition and cardiovascular disease in AYAs is unknown, but has been intensively studied in coronary heart disease (CHD) patients. For this patient group a relevant risk reduction for development of CHF by healthy nutrition was demonstrated (e.g. by 30 % with a Mediterranean diet or by 13 % following the criteria of “Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension”) [12–14]. Both diets are rich of fibers, fruits and vegetables, which mirrors the nutrition recommendations of the “Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung” (DGE) (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for recommendations of the DGE) [15]. In CHD patients an intensive, individualized nutrition counseling leads to an improvement of nutritional status and behavior and finally quality of life [13].

The INAYA trial reported here was performed to evaluate the feasibility and the impact of an intensified nutrition counseling in the particularly at risk population of AYAs.

Methods

Trial eligibility

AYAs aged from 18 to 39 years with at least one treatment related (e.g. anthracycline based chemotherapy or chest radiation) or at least one non-treatment related (nicotine abuse, diabetes mellitus, dyslipoproteinemia or hypertension) risk factor for cardiovascular disease were eligible. All AYAs had completed cancer treatment with curative intent, were currently considered in remission and were receiving aftercare within our multidisciplinary survivorship clinic.

The trial was approved by the institutional review board and registered (Clinical trial identifier DRKS00009883 on DRKS). All patients provided written informed consent before study entry.

Study design

Prior to baseline assessment and after 12 weeks the AYAs filled in a 3-day dietary record (“Freiburger Ernährungsprotokoll”) providing data to calculate the “Healthy Eating Index- European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition” (HEI-EPIC) [16].

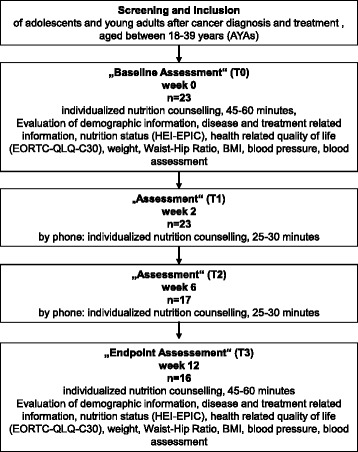

At baseline and after 12 weeks all AYAs got an intensified face-to-face nutrition counseling of 60 min performed by the same registered dietitian and based on the recommendations of the DGE (see Additional file 1: Table S1) [15]. Depending on the HEI-EPIC results and reported nutrition problems, recommendations of the DGE were modified and individually tailored to the needs of every AYA. Additionally, demographic information and medical history was collected at baseline. Waist-hip ratio (WHR), body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (RR), health-related quality of life (HRQOL, measured by EORTC QLQ-C30 [17]) and laboratory parameters (AST, ALT, HbA1c, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, C-reactive protein (CrP)) were assessed at baseline and after 12 weeks. At weeks 2 and six nutrition counseling of 30 min was repeated by telephone. (see Fig. 1 for study flowchart).

Fig. 1.

Study design

Healthy eating index - European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition

HEI-EPIC is an established instrument to evaluate the dietary behavior [18]. In the present pilot study the validated German version of HEI, the HEI-EPIC was used [16].

The HEI-EPIC distinguishes the following eight food groups: drinks, vegetables, fruits, cereals/potatoes, milk/dairy products, meat/sausages/fish/eggs, fats/oil and sweets/snacks. Based on a calculation described by Rüsten et al. 0–10 points for each group of food with up to 20 points for fruits, vegetables and drinks were calculated [16]. The sum score range from 0 to 110 points. A sum score ≤ 40 points indicate a bad, > 40–64 points a moderate and ≥ 65 points a good dietary behavior [16, 19].

Statistics

The primary endpoint was the rate of AYAs with a relevant improvement in nutritional behavior measured by HEI-EPIC (increase of at least 20 points) between weeks 0 and 12. Secondary endpoints were the change in median HEI-EPIC, the assessment of HRQOL by the EORTC QLQ-C30, WHR, BMI, RR and laboratory assessment regarding dyslipoproteinemia and cholesterinemia. Pre-post differences of the secondary endpoints were analyzed with Wilcoxon test for depended samples in an exploratory fashion. In addition, retrospective BMI sub groups were evaluated and patients were classified as: underweight (≤18.49 kg/m2; n = 5), normal weight (>18.5–24.99 kg/m2; n = 14) and overweight/obese (≥ 25.0–44.99 kg/m2; n = 4). No formal comparison of BMI subgroups was performed due to small numbers.

Sample size calculation

Based on our experience in the survivorship clinic, about 25 % of patients improve their nutritional behavior (increase in 20 points in HEI-EPIC) after a general nutrition counseling. With the intensive, individualized nutrition counseling at least 50 % of AYAs should improve their nutritional intake by 20 points on HEI-EPIC to regard the intervention as meaningful. The probability to accept the intervention as promising (improvement rate ≥50 % of AYAs), in spite of a true improvement rate of ≤25 % only, was set at 0.1 (type I error). The probability to erroneously reject the intervention as not sufficiently efficient (≤25 %), although the true improvement rate is meaningful (≥50 %) was set at 0.2 (type II error, corresponding to a power of 80 %). According to these parameters and using a standard single-stage phase II design with a one sided test and including 10 % drop outs, n = 21 AYAs had to be recruited [20].

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Twenty-three AYAs, 11 female and 12 male, were included in the INAYA study. Median age of cancer diagnosis was 16.0 years (range: 10.0–17.0 years), median age at time of study inclusion was 20.0 years (range: 19.0–23.0 years). Median time between diagnosis and study inclusion was 44 months (range: 11.0–237 months). Cancer diagnosis included sarcoma (n = 2), carcinoma (n = 2), blastoma (n = 1), hodgkin lymphoma (n = 12), or leukemia (n = 6).

All AYAs (100 %) presented treatment related risks factors for cardiovascular diseases that were application of anthracyclines (n = 22, 95.7 %), chest radiation (n = 9, 39.1 %) or both (n = 14, 60.9 %). Additional 8 (34.8 %) AYAs had non-treatment related risk factors: smoking (n = 5, 21.7 %), overweight with BMI > 25.0 kg/m2 (n = 4, 17.4 %) and hypertension (n = 1, 4.3 %), but no diabetes mellitus (n = 0, 0 %). One AYA had more than one non-treatment related risk factor.

Compliance rate was 100 % (n = 23) at baseline and week 2 but decreased to 73.9 % (n = 17) at week 6 and 69.6 % (n = 16) at week 12. Therefore, overall attrition rate was 30 %. Reasons for drop out were disease relapse (n = 1), lack of time due to high work load (n = 1), lack of time due other reasons (n = 3) and two were lost to follow up.

Primary endpoint

In 52.2 % (n = 12) of AYAs the median HEI-EPIC score improved by more than 20 points from baseline to week 12. Thus, the primary endpoint of an improvement in nutritional behavior by more than 20 points in more than 50 % of AYAs measured by HEI-EPIC was met, demonstrating the feasibility of the intensive, individualized nutrition counseling and a high rate of improvement in nutritional behavior.

Secondary endpoints

HEI-EPIC

At baseline, the median HEI-EPIC score was 47.0 points (range: 40.0–55.0 points) representing a moderate dietary behavior. A good, moderate and bad nutritional intake was seen in 4.3, 73.9 and 21.7 % of AYAs. At week 12, median HEI-EPIC score improved significantly to 65.0 points (range: 55.0–76.0 points) (p ≤ 0.001) representing a good dietary behavior. Good, moderate and bad nutritional intake was seen in 47.8, 52.2 and 0 % of AYAs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Nutritional behavior in AYAs at baseline and week 12

Nutrition scores improved significantly in all food groups, except meat/sausages/fish/eggs/soy products and fats/oil (Table 1).

Table 1.

Change in median nutrition intake of different HEI-EPIC food groups

| Food groups | Week 0 (T0) | Week 12 (T3) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| drinks | 4.8 (3.3–9.3) | 8.4 (6.9–10.1) | 0.001 |

| vegetables | 1.8 (0.8–2.4) | 3.1 (1.7–3.9) | 0.001 |

| fruits | 1.5 (0.0–2.4) | 2.4 (0.5–3.6) | 0.030 |

| cereals/cereals products/potatoes | 2.3 (1.7–2.9) | 2.9 (2.3–3.4) | 0.038 |

| milk/milk products/dairy products | 3.3 (1.3–2.9) | 1.8 (1.6–3.9) | 0.041 |

| meat/sausages/fish/eggs/soy products | 1.2 (0.7–1.8) | 1.5 (0.8–1.8) | 0.452 |

| fats/oil | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | 2.1 (1.8–2.6) | 0.178 |

| sweets/snacks/alcohol | 2.4 (1.4–2.8) | 0.9 (0.6–1.8) | 0.001 |

HEI-EPIC score numerically improved in all BMI subgroups (Table 2).

Table 2.

HEI-EPIC of different BMI groups

| BMI groups | HEI-EPIC score week 0 (T0) | HEI-EPIC score week 12 (T3) |

|---|---|---|

| underweight AYAs: | 49.0 (38.0–57.5) | 78.0 (57.0–80.5) |

| BMI <18.5 kg/m2

(n = 5) | ||

| normal weight AYAs: | 50.5 (45.8–56.3) | 62.5 (53.3–72.3) |

| BMI ≥18.5–24.9 kg/m2

(n = 14) | ||

| overweight AYAs: | 37.5 (27.3–44.0) | 60.0 (49.8–69.5) |

| BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2

(n = 4) |

Quality of life

For quality of life analysis we used the global health status/quality of life (GHS/QOL) score of the EORTC QLQ C-30 questionnaire. The median GHS/QOL score did not change and was 83.3 points (range: 66.7–91.7 points) at week 0 and 83.3 points (range: 66.7–91.7 points) at week 12 (p = 0.332) (Table 3). A clinical relevant improvement of GHS/QOL score (≥ 10 points) was seen in 21.7 % (n = 5) of AYAs. While normal weight patients did not improve their median GHS/QoL (83.3 at week 0 and 12), patients of under- or overweight seemed to increase the GHS/QoL score (underweight: 66.7 to 83.3; overweight 75.0 to 87.5 from week 0 to 12). Detailed results for functioning, symptom and single item scores of the EORTC QLQ C-30 questionnaire are shown in Additional file 1: Table S2.

Table 3.

Secondary endpoints: quality of life, BMI, blood pressure and WHR

| Selected secondary endpoints | Week 0 (T0) | Week 12 (T3) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.4 (19.7–23.9) | 20.4 (19.0–23.9) | 0.218 |

| Quality of life (GHS/QoL points) | 83.3 (66.7–91.7) | 83.3 (66.7–91.7) | 0.332 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 110/70 (105–135/60–90) | 110/75 (95–135/60–90) | 0.015/0.605 |

| Waist hip ratio (WHR) | 0.80 (0.69–0.97) | 0.77 (0.66–0.98) | 0.349 |

Body Mass Index (BMI)

At baseline 5 AYAs were underweight, 14 AYAs normal weight and 4 AYAs overweight according to WHO criteria. After nutrition counseling at week 12, the amount of normal weight AYAs increased to 17, with only four underweight and two overweight/obese AYAs remaining.

Before nutrition counseling 5 patients claimed weight loss as one of the goals of taking part in that trial. All of them reached their aim to lose weight. The overweight/obese patients (n = 4) lost a median of 4.3 kg (range: 1.4–7.9 kg).

The median BMI at baseline was 21.4 kg/m2 (range: 19.7–23.9 kg/m2) and 20.4 kg/m2 (range: 19.0–23.9 kg/m2) at week 12 (p = 0.218) (Table 3). In underweight and normal weight patients the median BMI remained unaffected 17.7 kg/m2 (range: 16.8–18.0 kg/m2) and 21.4 kg/m2 (range: 20.0–23.4 kg/m2) at baseline and 17.7 kg/m2 (range: 16.8–18.2 kg/m2) and 20.7 kg/m2 (range: 20.0–23.2 kg/m2) at week 12, respectively. In overweight patients a slight decrease in median BMI from 29.1 kg/m2 (range: 25.2–40.0 kg/m2) to 27.3 kg/m2 (range: 24.6–37.8 kg/m2) was noted.

Blood pressure (RR)

During the 12 weeks intervention period the median RR remained stable with 110/70 mmHg (range: 110–125/70–80 mmHg) at baseline and 110/75 mmHg (range: 105–125/70–80 mmHg) at week 12 (Table 3).

Waist-hip ratio (WHR)

All patients WHR were within the normal range <0.85 for women and <1.0 for men. Median WHR did not change significantly from baseline to week 12, neither in the overall population nor in the BMI subgroups.

Median WHR was 0.80 (range: 0.72–0.80) at baseline and 0.77 (range: 0.71–0.80) at week 12 (p = 0.349). 65.2 % (n = 15) had a lower and 30.4 % (n = 7) had a higher WHR in week 12 (Table 3). No relevant differences in WHR changes over time were noted within the BMI subgroups.

Biochemical parameters (AST, ALT, HbA1c, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, CRP)

Intensified nutrition counseling had no significant effect on biochemical parameters. Detailed results for AST and ALT, HbA1c, total-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and CRP are shown in Additional file 1: Table S3.

Discussion

This first, prospective life-style modification trial in the particular patient group of AYAs demonstrate the feasibility of an intensified, individual nutrition counseling and results in high rates of improvement in nutritional behavior. An improvement of more than 20 points was seen in 52.2 % (n = 12) of the AYAs. Thus, the primary endpoint of this study was met. The median HEI-EPIC score changed significantly from a moderate (47.0 points) to a good nutritional behavior (65.0 points). Overall, the number of AYAs with good nutritional behavior was increased by the INAYA intervention from one to 11.

The AYA population relevantly differs from the elderly survivor patients and prospective trials in this distinct setting are lacking. AYAs have to deal with a variety of relevant problems including educational and occupational issues, partnership and family planning, besides lifestyle and nutrition. Of note, compared to previously reported rates of healthy food intake of up to 18 % in elderly cancer survivors without nutrition counseling, the baseline rate in our population seemed to be even lower (n = 1, 4.3 %) [11].

Despite the particular vulnerability of the AYA population prospective trials about nutrition counseling are lacking. The majority of published nutrition intervention trials include either non-AYA or non-cancer patients. Nevertheless, similar to the INAYA trial, a large variety of trials in different patient population could demonstrate the feasibility and efficacy of lifestyle interventions.

A review of 21 trials about nutrition counseling in primary care setting demonstrated that moderate- or high-intensity counseling interventions, including use of interactive health communication tools, can reduce the consumption of saturated fat and increase the intake of fruit and vegetable and therefore improve nutritional behavior. The patient population included was very heterogeneous and is not comparable to AYAs [21]. In breast cancer patients, a randomized interventional trial showed a significant improvement in vegetable consumption 8 weeks after nutrition counseling [22]. In regard of dietary behavior, the best-investigated patient groups are those with hypertension or coronary heart disease (CHD). In these groups structured educational programs and intensified nutrition counseling improve dietary behavior and quality of life [23].

Although survivors usually have an increased risk of poor HRQOL, the baseline GHS/QoL score was relatively high (83.3 points) in our cohort [24]. HRQOL assessment refers to a multidimensional construct, considering the subjective perceptions of disease symptoms, treatment side effects as well as physical, emotional, social and cognitive functions. Therefore, it might be difficult to improve the overall HRQOL by the improvement of nutritional behavior.

Limitations of the INAYA study are the relatively low number of participants, limiting the interpretation of results particularly of the subgroup evaluations. Furthermore, the attrition rate of 30 % limits the follow up data. The availability for phone consultations was limited, mainly due to educational or occupational engagements of our AYA patients. Therefore, for future trials the follow up procedures should be carefully evaluated. One way could be to send nutrition information and reminders by e-Mail, Apps or SMS. Another possibility could be to extend the intervals and re-counsel the AYAs at the next regular aftercare appointment. The relatively short intervention and follow up period does not allow evaluating the sustained efficacy of the INAYA protocol. Further trials will need to confirm the sustainability of the INAYA approach, although periodical re-counseling will likely be necessary to ensure long-term healthy eating. Due to the single arm design a control-group is missing and the efficacy of the INAYA approach cannot be demonstrated. However, a high rate of 50 % of AYAs with an improvement in nutritional behavior was noted, clearly pointing towards further evaluation of the INAYA approach in a randomized setting.

Conclusion

Intensified nutrition counseling is feasible and seem to improve short-term dietary behavior of AYAs and thus potentially reduces the long-term risk for developing cardiovascular diseases. Thus, intensified lifestyle modification approaches flanked by long-term follow up are required in AYAs.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all patients who participated in this study, all participating clinicians who included patients, and all the staff engaged in this study.

Funding

The study and manuscript was prepared without any funding or contribution of persons not mentioned in the authors’ section.

Availability of data and materials

For dataset supporting the conclusions of this article please contact the author.

Authors’ contributions

JQ, JG, BK, GE, AS recruited patients, collected patient data, interpreted results of analyses, prepared, reviewed and input into each stage of the manuscript; GS, LV, DB, CB: interpreted results of analyses, prepared, reviewed and input into each stage of the manuscript; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The trial was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the local ethics committee “Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer Hamburg” on 19/05/2015 (reference number PV4978). Informed consent to participate in the INAYA study and to publish the results were obtained from all participants before study inclusion.

Abbreviations

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- AYA

Adolescents and young adults

- BMI

Body mass index

- CCSS

Childhood cancer survivor study

- CHD

Chronic heart disease

- CHF

Chronic heart failure

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- DGE

“Deutsche gesellschaft für ernährung”

- DRKS

Deutsches register klinischer studien

- e.g.

Exempli gratia

- EORTC QLQ-C30

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Qualitiy of Life Core Questionnaire 30

- GHS/QOL

Global health status/quality of life

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- HDL-cholesterol

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HEI-EPIC

Healthy eating index - European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition

- HRQOL

Health-related quality of life

- INAYA

Improved nutrition in AYAs

- LDL-cholesterol

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- RR

Blood pressure

- S

Supplement

- WHR

Waist-hip ratio

Additional file

10 guidelines of the German Nutrition Society (DGE) for a wholesome diet. Table S2. Results of EORTC QLQ C-30 questionnaire. Table S3. Change in blood values ASAT, ALAT, HbA1c, Total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and CrP. (DOCX 17 kb)

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, Alteri R, Robbins AS, Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):252–71. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolff SN, Nichols C, Ulman D, Miller A, Kho S, Lofye D, Milford M, Tracy D, Bellavia B, Armstrong L. Survivorship: an unmet need of the patient with cancer - implications of a survey of the Lance Armstrong Foundation (LAF) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(16_suppl):6032. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, Friedman DL, Marina N, Hobbie W, Kadan-Lottick NS, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castellino SM, Geiger AM, Mertens AC, Leisenring WM, Tooze JA, Goodman P, Stovall M, Robison LL, Hudson MM. Morbidity and mortality in long-term survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Blood. 2011;117(6):1806–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulrooney DA, Yeazel MW, Kawashima T, Mertens AC, Mitby P, Stovall M, Donaldson SS, Green DM, Sklar CA, Robison LL, et al. Cardiac outcomes in a cohort of adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: retrospective analysis of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. BMJ. 2009;339:b4606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tukenova M, Guibout C, Oberlin O, Doyon F, Mousannif A, Haddy N, Guerin S, Pacquement H, Aouba A, Hawkins M, et al. Role of cancer treatment in long-term overall and cardiovascular mortality after childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(8):1308–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson RE, Cadmus LA, Emond JA, Pierce JP. Physical activity, diet, adiposity and female breast cancer prognosis: a review of the epidemiologic literature. Maturitas. 2010;66(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rock CL, Demark-Wahnefried W. Can lifestyle modification increase survival in women diagnosed with breast cancer? J Nutr. 2002;132(11 Suppl):3504S–7. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3504S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pierce JP, Newman VA, Flatt SW, Faerber S, Rock CL, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, Gold EB, Hollenbach KA, Wasserman L, et al. Telephone counseling intervention increases intakes of micronutrient- and phytochemical-rich vegetables, fruit and fiber in breast cancer survivors. J Nutr. 2004;134(2):452–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rock CL, Flatt SW, Byers TE, Colditz GA, Demark-Wahnefried W, Ganz PA, Wolin KY, Elias A, Krontiras H, Liu J, et al. Results of the Exercise and Nutrition to Enhance Recovery and Good Health for You (ENERGY) Trial: A Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention in Overweight or Obese Breast Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(28):3169–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer DK, Terrin NC, Menon U, Kreps GL, McCance K, Parsons SK, Mooney KH. Health behaviors in cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(3):643–51. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.643-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Chen Y, Kawashima T, Yasui Y, Leisenring W, Stovall M, Chow EJ, Sklar CA, Mulrooney DA, et al. Modifiable risk factors and major cardiac events among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3673–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chow EJ, Chen Y, Kremer LC, Breslow NE, Hudson MM, Armstrong GT, Border WL, Feijen EA, Green DM, Meacham LR, et al. Individual prediction of heart failure among childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;10:3643–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipshultz SE, Adams MJ, Colan SD, Constine LS, Herman EH, Hsu DT, Hudson MM, Kremer LC, Landy DC, Miller TL, et al. Long-term cardiovascular toxicity in children, adolescents, and young adults who receive cancer therapy: pathophysiology, course, monitoring, management, prevention, and research directions: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(17):1927–95. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a88099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.V.) GNSDGfEe . 10 guidelines of the German Nutrition Society (DGE) for a wholesome diet. 9 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruesten A V. Die Bewertung der Lebensmittelaufnahme mittels eines, Healthy Eating Index‘(HEI-EPIC) Ernährungs Umschau. 2009;8:450–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hiza HA, Kuczynski KJ, Kahle LL, Krebs-Smith SM. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(4):569–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion USDoA: The Healthy Eating Index: http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/publications/hei/HEI89-90report.pdf. 1995.

- 20.Fleming TR. One-sample multiple testing procedure for phase II clinical trials. Biometrics. 1982;38(1):143–51. doi: 10.2307/2530297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pignone MP, Ammerman A, Fernandez L, Orleans CT, Pender N, Woolf S, Lohr KN, Sutton S. Counseling to promote a healthy diet in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(1):75–92. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho SW, Kim JH, Lee SM, Lee SM, Choi EJ, Jeong J, Park YK. Effect of 8-week nutrition counseling to increase phytochemical rich fruit and vegetable consumption in korean breast cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr Res. 2014;3(1):39–47. doi: 10.7762/cnr.2014.3.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook SL, Nasser R, Comfort BL, Larsen DK. Effect of nutrition counselling on client perceptions and eating behaviour. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2006;67(4):171–7. doi: 10.3148/67.4.2006.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, Tsao JCI, Recklitis C, Armstrong G, Mertens AC, Robison LL, Ness KK. Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17(2):435–46. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

For dataset supporting the conclusions of this article please contact the author.