Abstract

Background

Exercise plays a significant role in learning and memory. The present study focuses on the hippocampal corticosterone (CORT), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), glucose, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels in preventive, therapeutic, and protective exercises in stressful conditions.

Methods

Forty male rats were randomly divided into four groups: the control group and the preventive, therapeutic, and protective exercise groups. The treadmill running was applied at a speed of 20–21m/min and a chronic stress of 6 hours/day for 21 days. Subsequently, the variables were measured in the hippocampus.

Results

The findings revealed that the hippocampal CORT levels in the preventive exercise group had a significant enhancement compared to the control group. In the protective and particularly the therapeutic exercise groups, the hippocampal CORT levels declined. Furthermore, the hippocampal BDNF levels in the preventive and the therapeutic exercise groups indicated significantly decreased and increased, respectively, in comparison with the control group. In the preventive exercise group, however, the hippocampal glucose level turned out to be substantially higher than that in the control group.

Conclusion

It appears that the therapeutic exercise group had the best exercise protocols for improving the hippocampal memory mediators in the stress conditions. By contrast, the preventive exercise group could not improve these mediators that had been altered by stress. It is suggested that exercise time, compared to stress, can be considered as a crucial factor in the responsiveness of memory mediators.

Keywords: Stress, Exercise, Corticosterone, Interleukin-1βeta, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, Glucose

Introduction

The stress conditions have increased in societies today. They represent a collection of events which begin with a stressor and accelerate a response in the body, particularly in the brain (1). Therefore, they are one of the main factors contributing to the memory deficit (2, 3). According to our previous studies, the impairment of memory processes has been demonstrated by using chronic stress (2,3). Based on our other previous documents, exercise can be regarded as a beneficial manner in the improvement of learning and memory in stress conditions and even Alzheimer disease (4–8). These studies have confirmed that different exercise protocols ameliorate cognitive and memory function (4–6). Accordingly, exercise could alter brain functions in the stressful conditions and neurodegenerative diseases (4–9). It is demonstrated that stress and exercise affect the secretion of glucocorticoids hormones (corticosterone in rats; CORT) from the adrenal glands (2, 10–13). In addition, glucocorticoids hormones can change some neuromodulators in the brain, such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) (14), glucose (15), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (16), and other biochemical factors. CORT and IL-1β influence memory processing and neural plasticity and impair the memory consolidation (2, 17). On the other hand, BDNF and glucose improve memory (2, 18). BDNF has emerged as a major synaptogenesis regulator and synaptic plasticity mechanism underlying learning and memory in the brain (19). It appears that exercise, similar to stress, could be involved in regulating the levels of memory mediators. Since the effects of different exercise protocols on the levels of memory mediators in the hippocampus have not been fully clarified and the hippocampus is a main memory structure that is involved in both stress and exercise (20, 21), the present study focuses on this area. Stress and exercise can alter neurochemistry, plasticity, neurotoxicity, neurogenesis, glucocorticoid receptor regulation, and neuronal morphology in neuronal circuits of hippocampus (DG and CA1–CA4) (3, 22–24).

In human communities, different exercise protocols may be repeatedly observed in humans’ lifetime. For example, an exerciser might withdraw physical activity under stressful conditions (preventive exercise). In other groups, exercise might perform during exposure to stressor (protective exercise). Even individuals may perform an exercise after stress conditions to improve the physiologic system of their bodies (therapeutic exercise). Hence, the present study investigates the effect of preventive, therapeutic, and protective exercise (exercise before, after, and during chronic stress, respectively) on the alteration of BDNF (as the main index of neurogenesis and memory), CORT, IL-1β, and glucose levels (as accessory biochemical indexes of memory) in hippocampus of rats under chronic stress.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Forty male Wistar rats, with an initial weight of 250–300 g, were utilized as experimental subjects. The animals were housed under an artificial light (12-h light/dark, lights on at 7:00 a.m) and temperature (22±2°C) controlled condition, with food and water available ad libitum. The experiments lasted 42 days. All experiments on the animals were approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Science and were performed in accordance with National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80–23, revised in 1996).

The animals were randomly divided into four groups (n=10 in each group) as follows: the control group: the rats were put on the treadmill without running for 1 hour/day. The preventive exercise group (exercise before stress): the rats were exercised for 21 days before applying the 21-day stress. The therapeutic exercise (exercise after stress) group: the rats were under stress for 21 days and then were exercised for 21 days. The protective exercise (exercise during stress) group: the rats had exercise associated with chronic stress (4–6).

Experimental procedures

Stress protocol

The rats were tightly fitted in separate flat bottom Plexiglas cylindrical restrainers (Razi Rad Co., Tehran, Iran) in medium size for the rats with a weight of 250–300 g (5 cm in diameter and 20 cm in length) for 6 hours/day (8:00–14:00) in the chronic stress model (2–5). Several holes in the walls of the cylinders provided fresh air. In addition, it was not possible for the rats to move, and the restriction of the locomotion occurred in them. Restraint stress was employed as an important common stress-inducing model of emotional stress (25–27).

Exercise protocol

In the exercised groups, the animals ran on a rodent treadmill (Technic Azma Co., Tabriz, Iran). The rats became habituated to treadmill running in order to minimise novelty stress for three days before the experiments. The exercise protocol consisted of 1 hour/day/for 6 consecutive days at 20–21 m/min and slope of 0° (5). The rats received approximately 0.3 mA electric shock at 3 seconds to sparingly promote their running from the grid located just behind the treadmill (28). After warm-up, the speed and the duration of treadmill running were kept constant at 20 m/min for 1 hour running throughout the exercise period.

Assessment of corticosterone, IL-1β, BDNF, and glucose levels in hippocampus

After decapitation and removal of the animals’ brains from their skulls, the hippocampi were instantly dissected on dry ice. Each hippocampus was separately immersed in ProblockTm-50, EDTA free (Gold Bio Co., USA) and phosphate buffer solution (PBS buffer, 0.01 M, pH 7.4). Indeed, this solution contained complete protease inhibitor cocktail. The hippocampi were homogenised and centrifuged in a cooled centrifuge (4°C, 10000 g for 20 min). Following that, the supernatant was separated and stored at −80°C until the assessment. The commercial ELISA kit was utilised to assess the corticosterone levels in hippocampus (DRG Co., Marburg, Germany). The BDNF levels in the homogenated hippocampus were measured by the ELISA kit of BDNF (Promega Co., Sweden). Additionally, the ELISA kit (Koma biotech Co., Korea) was employed to measure the serum IL-1β level. The serum glucose level (fed glucose, not fast glucose) was measured by the glucose oxidase method (Pars Azmun Co., Tehran, Iran).

Measurement of brain and hippocampus weights

At the end of the experiments, after removing the brains and the hippocampi from the skulls, their weights were measured.

Data Analysis

All data were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple groups. In the current study, the values are presented as mean± standard error of the mean (SEM), where P<0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

Assessment of serum CORT, BDNF, IL-1β, and glucose levels

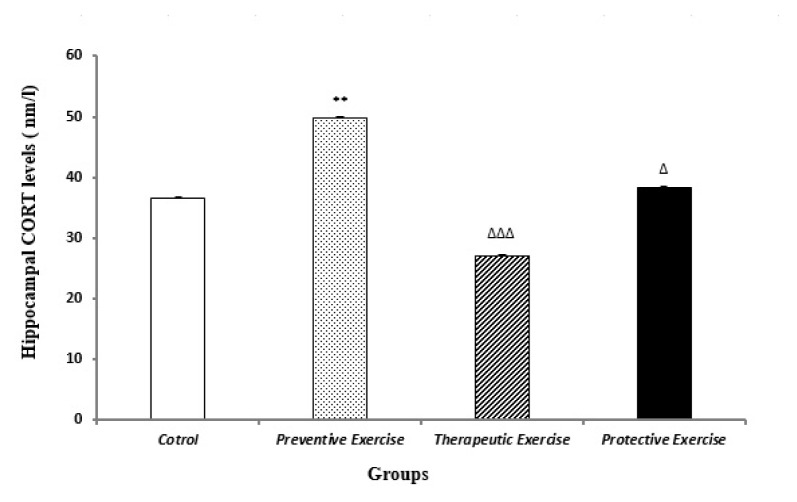

There was a significant enhancement (P<0.05) in the CORT levels of the preventive exercise (exercise before stress) group when compared to the control group. Nevertheless, the CORT levels substantially decreased in the therapeutic exercise (exercise after stress) and the protective exercise (exercise during stress) groups (P<0.001 and P<0.05, respectively) compared to the preventive exercise group (Figure 1). Hence, the protective and particularly the therapeutic exercises decreased the CORT levels more than the preventive exercise.

Figure 1.

The comparison of different protocols of exercise on the hippocampal corticosterone (CORT) levels (nmol/L) in the different groups (n=10). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (ANOVA test, Tukey’s post- hoc test); **P<0.01 when compared to the control group; ΔP<0.05 and ΔΔΔP<0.001 when compared to the preventive exercise group.

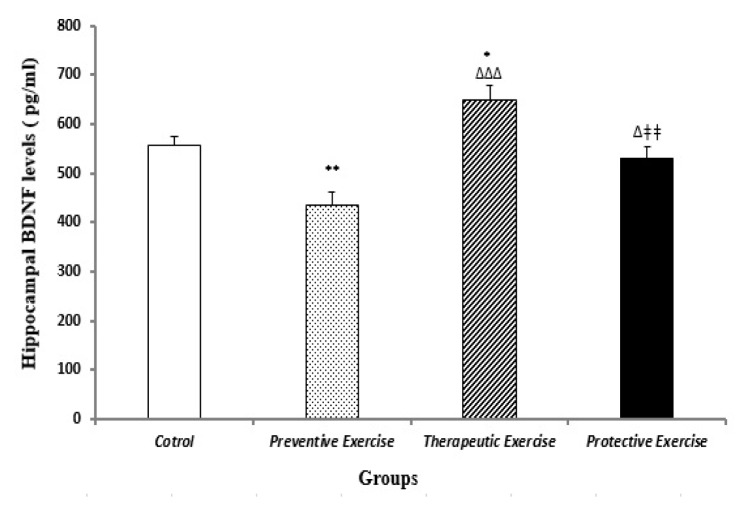

The BDNF levels of the preventive and the therapeutic exercise groups were considerably (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively) different from that of the control group. Moreover, there were significant changes regarding the BDNF levels between the therapeutic and the preventive exercise groups (P<0.001 and P<0.05, respectively) compared to the preventive exercise group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The comparison of different protocols of exercise on the hippocampal BDNF levels (pg/ml) in the different groups (n=10). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (ANOVA test, Tukey’s post- hoc test); *P<0.05, **P<0.01 when compared to the control group; ΔP<0.05 and ΔΔΔP<0.001 when compared to the preventive exercise group; ΔΔP<0.01 when compared to the therapeutic exercise group.

The BDNF level showed a significant (P<0.01) decrease in the protective exercise group compared to the therapeutic exercise group (Figure 2).

The IL-1β level did not show any significant differences between all groups when they were compared to the control group and to each other. However, the IL-1β level decreased more in the therapeutic exercise group in comparison with the other exercise groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The comparison of different protocols of exercise on the serum IL-1β levels (pg/ml) in the different groups (n=10). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (ANOVA test, Tukey’s post- hoc test) when compared to the control group and together. There were not significant differences between all groups.

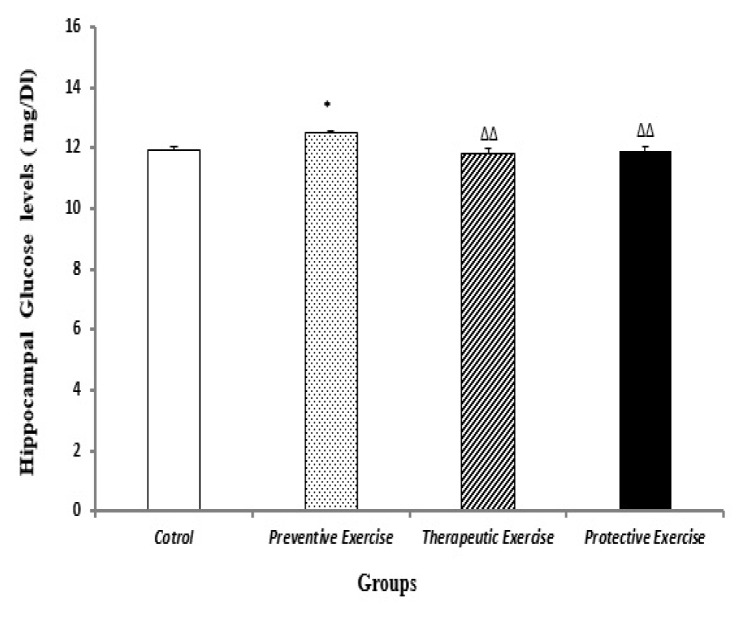

In the preventive exercise group, the glucose level was substantially (P<0.05) higher than that in the control group (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The comparison of different protocols of exercise on the hippocampal glucose levels (mg/Dl) in the different groups (n=10). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (ANOVA test, Tukey’s post- hoc test); *P<0.05 when compared to the control group; ΔΔP<0. 01 when compared to the preventive exercise group.

As it is shown in Figure 4, the glucose levels in the therapeutic and the protective exercise groups were noticeably (P<0.01 in both of them) lower than that in the preventive exercise group (Figure 4).

Correlations between the behavioral test and the biochemical parameters

In our previous studies, memory was evaluated by the passive avoidance test in the preventive, therapeutic, and protective exercise groups (4, 6). The findings of the present study did not indicate any significant correlations between the hippocampal CORT, BDNF, IL-1β, and glucose levels separately with memory in all of the experimental groups (not presented here as a graph).

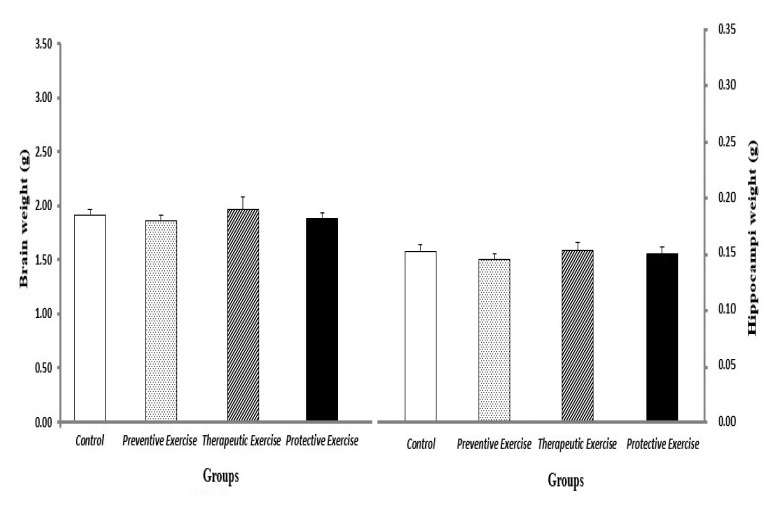

Measurement of brain and hippocampus weights

The weights of brains and hippocampi did not show any significant differences between all groups when they were compared with the control group and with each other (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The comparison of different protocols of exercise on the brain and hippocampus weights (gr) in the different groups (n=10). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (ANOVA test, Tukey’s post- hoc test when compared to the control group and together. There were not significant differences between all groups.

Discussion

The findings of the current study demonstrated that the preventive, therapeutic, and protective exercises changed the CORT levels in the hippocampus. They also revealed that the hippocampal CORT level was higher in the preventive exercise than the other exercise protocols (Figure 1). This indicated no dominant effect of the preventive exercise on the main stress indexes such as the hippocampal CORT levels. In point of fact, the preventive exercise was not adequate for preventing the stressful challenges. Of course some previous studies reported that exercise could act as a stressor and activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (29–31). In the present study, it appears that the elevated hippocampal CORT levels could result from the chronic stress induced after exercise. In other researches as well as our previous studies, it was reported that the CORT level crossed from the blood brain barrier (BBB) to brain with some limitations. Hence, the hippocampal CORT levels followed the serum CORT levels (2, 13, 32). In addition, the present findings confirmed that the protective and particularly the therapeutic exercises produced no significant decreases in the hippocampal CORT levels compared to the control group (Figure 1). Kannangara et al. reported a noteworthy reduction in the CORT levels in the central nervous system by exercise (33). Furthermore, some reports demonstrated such different responses on the glucocorticoid levels after exercise as enhancement (34), reduction (35), and no changes (36) in the glucocorticoid levels. Consequently, this difference might be related to duration and types of exercise and probably exercise time.

On the other hand, the reduction and enhancement of hippocampal BDNF levels were observed in the preventive and the therapeutic exercises, respectively, compared to the normal condition. Additionally, the protective exercise had an intermediate condition in the hippocampal CORT and BDNF levels compared to the other exercise protocols in stressful conditions in the current study (Figure 2). Previous studies reported a relationship between the enhancement of glucocorticoid levels and the reduction of BDNF mRNA as well as their involvement in memory functions of rat’s hippocampus (2, 37–39). However, although the results of this study demonstrated this relationship, there is no significant negative correlation between the hippocampal CORT and BDNF levels in the preventive, therapeutic, and protective exercises in the stressed rats.

Initially, it appears that the preventive exercise may protect the hippocampus against the reduction in the hippocampal BDNF level; nonetheless, the present findings did not confirm the useful effect of the preventive exercise on the BDNF levels. Exercise increases the hippocampal BDNF levels in hippocampus compared to the normal condition (40, 41). The present findings could explain some of the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of the protective and particularly the therapeutic exercises on reducing stress and probably memory functions. Therefore, it appears that the protective and the therapeutic exercises can probably affect synaptogenesis, plasticity, dendrite proliferation, and neurogenesis in the hippocampus (42).

Other comparisons of the preventive, therapeutic, and protective exercise illustrated that different exercise protocols did not change the IL-1β level in hippocampus (Figure 3). Some studies reported that stress increased the central IL-1β level (43, 44). On the other hand, it was also demonstrated that IL-1β is an important neurochemical mediator in the stress-induced stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the secretion of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) and corticosterone (CORT) (45, 46). Hence, the present findings suggested that the exercise before, after, and during stress could keep the balance of hippocampal IL-1 β level in the stress conditions. Conversely, Barrientos et al. reported that exercise had no effect on the basal hippocampal IL-1β level (44).

According to other our present data, the hippocampal glucose level increased in the preventive exercise and decreased in the therapeutic and the protective exercise groups (Figures 3 and 4). Accordingly, all of the current data suggested that the changes in the hippocampal BDNF and glucose levels followed the hippocampal CORT levels. In contrast, the inflammatory factor such as IL-1β level did not follow the changes in the CORT levels of hippocampus in the present study.

In our previous studies, memory was assessed in the preventive, therapeutic, and protective exercise groups by passive avoidance test (4, 6). In these studies, memory functions at the end of the experimental period did not show any significant differences in the preventive and the protective exercise groups (5, 6). However, memory improved in the therapeutic exercise group (6). In the present study, the findings did not indicate a significant correlation between the hippocampal CORT, BDNF, IL-1β, and glucose levels separately with memory in all experimental groups. Therefore, the correlations between memory functions and memory mediators proposed that multiple factors (such as hippocampal CORT, IL-1β, BDNF, glucose, and perhaps many other factors) may, together but not alone, synergistically affect the memory in the interaction exercise with stress.

Conclusion

The therapeutic exercise had been the best exercise protocol in reducing the harmful effects of psychological stress on memory mediators in the hippocampus. It appears that the therapeutic exercise had neuroprotective properties and could reverse the harmful effects of stress in the hippocampus. However, the preventive exercise could not improve the alteration induced by the chronic stress. This suggested that the exercise time, with respect to stress conditions, is an important factor for the responsiveness of memory mediators in the hippocampus. Accordingly, evaluating other factors and gene expression involved in the stress and the exercises is highly recommended.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mehdi Hedayati for his valuable assistance. Conduction of the present research was made possible through the supports received from Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they don’t have any conflict of interest.

Funds

The present study was financially supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: MR, HA

Analysis and interpretation of the data: MR, NH

Drafting of the article: MR, NH, HA, MRS

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: MR, NH, HA, MRS

Final approval of the article: MR, NH, HA, MRS

Provision of study materials or patients: MR, HA

Statistical expertise: MR

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: MRS

References

- 1.Dhabhar FS, McEwen BS. Acute stress enhances while chronic stress suppresses cell-mediated immunity in vivo: a potential role for leukocyte trafficking. Brain Behav Immun. 1997;11(4):286–306. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1997.0508. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/brbi.1997.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radahmadi M, Alaei H, Sharifi MR, Hosseini N. Effects of different timing of stress on corticosterone, BDNF and memory in male rats. Physiol Behav. 2015;139:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.12.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radahmadi M, Hosseini N, Nasimi A. Effect of chronic stress on short and long-term plasticity in dentate gyrus; Study of recovery and adaptation. Neuroscience. 2014;280C:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radahmadi M, Alaei H, Sharifi MR, Hosseini N. The effect of synchronized running activity with chronic stress on passive avoidance learning and body weight in rats. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(4):430–437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radahmadi M, Alaei H, Sharifi MR, Hosseini N. The Effect of Synchronized Forced Running with Chronic Stress on Short, Mid and Long-term Memory in Rats. Asian J Sports Med. 2013;4(1):54–62. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radahmadi M, Alaei H, Sharifi MR, Hosseini N. Preventive and therapeutic effect of treadmill running on chronic stress-induced memory deficit in rats. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015;19(2):238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2014.04.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosseini N, Alaei H, Reisi P, Radahmadi M. The effect of treadmill running on memory before and after the NBM-lesion in rats. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013;17(4):423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.12.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosseini N, Alaei H, Reisi P, Radahmadi M. The effect of treadmill running on passive avoidance learning in animal model of Alzheimer disease. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(2):187–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng H, Liu Y, Li W, Yang B, Chen D, Wang X, et al. Beneficial effects of exercise and its molecular mechanisms on depression in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;168(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.10.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akirav I, Kozenicky M, Tal D, Sandi C, Venero C, Richter-Levin G. A facilitative role for corticosterone in the acquisition of a spatial task under moderate stress. Learning & memory. 2004;11(2):188–195. doi: 10.1101/lm.61704. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/lm.61704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radahmadi M, Shadan F, Karimian SM, Sadr SS, Nasimi A. Effects of stress on exacerbation of diabetes mellitus, serum glucose and cortisol levels and body weight in rats. Pathophysiology. 2006;13(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2005.07.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pathophys.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McEwen BS. The neurobiology of stress: from serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Res. 2000;886(1–2):172–189. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02950-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02950-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radahmadi M, Alaei H, Sharifi MR, Hosseini N. Effect of forced exercise and exercise withdrawal on memory, serum and hippocampal corticosterone levels in rats. Exp Brain Res. 2015;233:2789–2799. doi: 10.1007/s00221-015-4349-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00221-015-4349-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li S, Wang C, Wang W, Dong H, Hou P, Tang Y. Chronic mild stress impairs cognition in mice: from brain homeostasis to behavior. Life Sci. 2008;82(17–18):934–942. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.02.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waeber G, Calandra T, Bonny C, Bucala R. A role for the endocrine and pro-inflammatory mediator MIF in the control of insulin secretion during stress. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15(1):47–54. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199901/02)15:1<47::aid-dmrr9>3.0.co;2-j. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002(SICI)1520-7560(199901/02)15:1<47::AID-DMRR9>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaaf MJ, De Kloet ER, Vreugdenhil E. Corticosterone effects on BDNF expression in the hippocampus. Implications for memory formation. Stress. 2000;3(3):201–208. doi: 10.3109/10253890009001124. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10253890009001124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rachal Pugh C, Fleshner M, Watkins LR, Maier SF, Rudy JW. The immune system and memory consolidation: a role for the cytokine IL-1beta. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25(1):29–41. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00048-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7634(00)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Messier C. Glucose improvement of memory: a review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;490(1–3):33–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunha C, Brambilla R, Thomas KL. A simple role for BDNF in learning and memory? Front Mol Neurosci. 2010;3:1–14. doi: 10.3389/neuro.02.001.2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/neuro.02.001.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carboni L, Piubelli C, Pozzato C, Astner H, Arban R, Righetti PG, et al. Proteomic analysis of rat hippocampus after repeated psychosocial stress. Neuroscience. 2006;137(4):1237–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.045. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stranahan AM, Khalil D, Gould E. Running induces widespread structural alterations in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Hippocampus. 2007;17(11):1017–22. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nacher J, Pham K, Gil-Fernandez V, McEwen BS. Chronic restraint stress and chronic corticosterone treatment modulate differentially the expression of molecules related to structural plasticity in the adult rat piriform cortex. Neuroscience. 2004;126(2):503–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Kloet E, Datson N, Revsin Y, Champagne D, Oitzl M. Brain corticosteroid receptor function in response to psychosocial stressors. In: Pfaff DW, Kordon C, Chanson P, Christen Y, editors. Hormones and Social Behaviour. Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2008. pp. 131–150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-79288-8_10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moorthi P, Premkumar P, Priyanka R, Jayachandran K, Anusuyadevi M. Pathological changes in hippocampal neuronal circuits underlie age-associated neurodegeneration and memory loss: Positive clue toward SAD. Neuroscience. 2015;301:90–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.062. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avishai-Eliner S, Eghbal-Ahmadi M, Tabachnik E, Brunson KL, Baram TZ. Down-regulation of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) precedes early-life experience-induced changes in hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor mRNA. Endocrinology. 2001;142(1):89–97. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.7917. http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/en.142.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dayas C, Buller K, Day T. Neuroendocrine responses to an emotional stressor: evidence for involvement of the medial but not the central amygdala. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11(7):2312–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00645.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jongkamonwiwat N, Krityakiarana W. The neuroprotective effects of voluntary exercise in a restraint stress model. ScienceAsia. 2012;38(3):250–255. http://dx.doi.org/10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2012.38.250. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saadipour K, Sarkaki A, Alaei H, Badavi M, Rahim F. Forced exercise improves passive avoidance memory in morphine-exposed rats. Pak J Biol Sci. 2009;12(17):1206–1211. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2009.1206.1211. http://dx.doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2009.1206.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Contarteze RVL, Manchado FDB, Gobatto CA, De Mello MAR. Stress biomarkers in rats submitted to swimming and treadmill running exercises. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2008;151(3):415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.03.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell JE, Király MA, Atkinson DJ, D’souza AM, Vranic M, Riddell MC. Regular exercise prevents the development of hyperglucocorticoidemia via adaptations in the brain and adrenal glands in male Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299(1):R168–176. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00155.2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00155.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ke Z, Yip SP, Li L, Zheng X-X, Tong K-Y. The effects of voluntary, involuntary, and forced exercises on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and motor function recovery: a rat brain ischemia model. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016643. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karssen AM, Meijer OC, van der Sandt IC, Lucassen PJ, de Lange EC, de Boer AG, et al. Multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein hampers the access of cortisol but not of corticosterone to mouse and human brain. Endocrinology. 2001;142(6):2686–2694. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/endo.142.6.8213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kannangara TS, Webber A, Gil-Mohapel J, Christie BR. Stress differentially regulates the effects of voluntary exercise on cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of mice. Hippocampus. 2009;19(10):889–897. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20514. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tharp GD. The role of glucocorticoids in exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports. 1975;7(1):6–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/00005768-197500710-00003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viru M, Litvinova L, Smirnova T, Viru A. Glucocorticoids in metabolic control during exercise: glycogen metabolism. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 1994;34(4):377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dellwo M, Beauchene RE. The effect of exercise, diet restriction, and aging on the pituitary--adrenal axis in the rat. Exp Gerontol. 1990;25(6):553–562. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(90)90021-s. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0531-5565(90)90021-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith MA, Cizza G. Stress-induced changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression are attenuated in aged Fischer 344/N rats. Aging. 1996;17(6):859–864. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(96)00066-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0197-4580(96)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith MA, Makino S, Kvetnansky R, Post RM. Effects of stress on neurotrophic factor expression in the rat brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;771:234–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44684.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith MA, Makino S, Kvetnansky R, Post RM. Stress and glucocorticoids affect the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 mRNAs in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1995;15(3 Pt 1):1768–1777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01768.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC. Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(6):295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02143-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansson AC, Sommer WH, Metsis M, Stromberg I, Agnati LF, Fuxe K. Corticosterone actions on the hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression are mediated by exon IV promoter. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18(2):104–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01390.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(3):266–270. doi: 10.1038/6368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Connor KA, Johnson JD, Hansen MK, Wieseler Frank JL, Maksimova E, Watkins LR, et al. Peripheral and central proinflammatory cytokine response to a severe acute stressor. Brain Res. 2003;991(1–2):123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barrientos RM, Frank MG, Crysdale NY, Chapman TR, Ahrendsen JT, Day HE, et al. Little exercise, big effects: reversing aging and infection-induced memory deficits, and underlying processes. J Neurosci. 2011;31(32):11578–11586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2266-11.2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2266-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gadek-Michalska A, Bugajski J. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) in stress-induced activation of limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis. Pharmacol Rep. 2010;62(6):969–982. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(10)70359-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1734-1140(10)70359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connor TJ, Song C, Leonard BE, Merali Z, Anisman H. An assessment of the effects of central interleukin-1beta, −2, −6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha administration on some behavioural, neurochemical, endocrine and immune parameters in the rat. Neuroscience. 1998;84(3):923–33. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00533-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]